Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 12

Patient satisfaction, health care resource utilization, and acute headache medication use with galcanezumab: results from a 12-month open-label study in patients with migraine

Authors Ford JH, Foster SA, Stauffer VL, Ruff DD, Aurora SK, Versijpt J

Received 4 August 2018

Accepted for publication 5 October 2018

Published 13 November 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 2413—2424

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S182563

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Janet H Ford,1 Shonda A Foster,1 Virginia L Stauffer,1 Dustin D Ruff,1 Sheena K Aurora,1 Jan Versijpt2

1Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN 46225, USA; 2Department of Neurology – Headache and Facial Pain Clinic, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (UZ Brussel), 1090 Brussels, Belgium

Background: Effects of galcanezumab, a monoclonal antibody against calcitonin gene-related peptide, on patient satisfaction, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and acute medication use were evaluated in a long-term, open-label study in patients with migraine.

Methods: Patients with episodic (78.9%) or chronic migraine (21.1%) were evaluated in the CGAJ study, an open-label study with 12-month treatment period. Galcanezumab 120 mg (with a loading dose of 240 mg) or 240 mg was administered subcutaneously once a month during treatment period. A self-rated scale, Patient Satisfaction with Medication Questionnaire–Modified (PSMQ-M), was used to measure satisfaction levels. Participants reported HCRU for the previous 6 months at baseline and that which occurred since the patient’s last study visit during treatment period. Acute headache medication use for migraine or headache for the past month was self-reported by participants at baseline and at each monthly visit during treatment period.

Results: At Months 1, 6, and 12, at least 69% of patients treated with galcanezumab responded positively for overall satisfaction, preference over prior treatments, and less impact from side effects. There were within-group reductions from baseline in migraine-specific HCRU (per 100 person-years) with galcanezumab for health care professional visits (173.4 to 59.6), emergency room visits (20.2 to 4.7), and hospital admissions (3.7 to 0.4) during treatment period. Statistically significant reductions in HCRU were observed for some events. There were significant within-group reductions from baseline in mean number of days/month with acute headache medication use for migraine or headache at each monthly visit during treatment period (overall change: -5.1 for galcanezumab 120 mg/240 mg; p<0.001).

Conclusion: Results from this long-term, open-label study suggest that treatment with galcanezumab is likely to lead to high patient satisfaction with treatment as well as meaningful reductions in migraine-specific HCRU and acute headache medication use in people with migraine.

Keywords: migraine, galcanezumab, open-label, HCRU, satisfaction, acute medication

Introduction

Migraine is a neurological disease characterized by severe attacks of headache, which are generally unilateral in nature and are accompanied by hypersensitivity to environmental stimuli.1,2 Depending on the frequency of headaches, patients may experience either chronic migraine (≥15 headache days per month, of which at least eight are migraine) or episodic migraine (<15 headache days per month).3 The episodic form is more prevalent (11.0%) than the chronic form (0.5%).4 With >10% of the world’s population suffering from this debilitating disease,5 migraine is rated as the second leading cause of disability worldwide.6 Migraine induces moderate-to-severe pain, impairs patient functioning, and at times requires bed rest.7

The goals of migraine treatment include pain relief and restoring function, reducing migraine attack frequency, preventing chronification, and management of existing comorbidities. Clinician and patient decision on treatments is based on the migraine headache frequency (episodic or chronic migraine), levels of impairment, previous treatment history, and patient preference.2 Acute therapies (eg, triptans, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], ergots) aim to provide relief from migraine symptoms and render the patient free from pain and other symptoms as quickly as possible (ideally in <2 hours), without recurrence and with minimal adverse events.2,8–11 When acute treatments are not effective in controlling migraine symptoms, patients may choose to seek care in an emergency department setting. Emergency care utilization in patients with migraine is high, and in some countries, emergency care is reported by one out of every four patients annually.12–14 Use of migraine preventive treatments has demonstrated a reduction in such undesirable health outcomes and in health care resource utilization (HCRU).15 The role of preventive medications is to decrease overall clinical characteristics of migraine including frequency, intensity, and duration of attacks, to improve responsiveness to acute therapy, and to reduce migraine-related disability. The current standard-of-care therapies for migraine prevention, all of which are oral, include antiepileptics, β-blockers, antidepressants, onabotulinumtoxinA, and calcium-channel blockers.2,16

In regard to patients’ preferences for preventive treatment, the ideal scenario is access to medications that possess high efficacy, have fewer side effects, and with lower dosing frequency.17 Studies show that the current migraine preventive options are underutilized18 and are associated with high discontinuation rates due to tolerability issues and lack of efficacy.19–22 In the US, nearly 50% and 80% of people with migraine who are prescribed a preventive medication discontinue it 60–90 days after initiation and are no longer on therapy 12 months after initiation, respectively.20,23,24 A large proportion of preventive medication users often have a history either of prior medication failures or of switching treatments.17,21 As a result, there is a high risk of patients not achieving meaningful reductions in headache with currently available preventives. This leads to many people with migraine relying solely on acute medications for managing the disease.19,21,22 Overuse of acute medications has been shown to result in increases in migraine frequency, migraine chronification, and occurrence of medication overuse headaches.25–27 Increases in frequency of migraine attacks and medication overuse headaches not only adversely impact patient functioning15,28 but also has been shown to result in an increased HCRU.15,29,30

Galcanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to calcitonin gene-related peptide, belongs to a novel class of molecules specifically designed for migraine prevention, unlike currently available preventives.31 In two phase 232,33 and three phase 3 studies,34–36 treatment with galcanezumab versus placebo led to significant reductions in the number of migraine headache days (MHDs) per month in people with episodic and chronic migraine. Another measure of successful migraine preventive treatment is the reduction of acute medication use for migraine. In phase 3 studies in patients with episodic and chronic migraine, treatment with galcanezumab led to significant reductions in number of MHDs with acute medication use per month.34–36 Study CGAJ was a 12-month, open-label study, part of the phase 3 development program for migraine prevention. People with episodic or chronic migraine were included in the study and were assigned to one of two treatment arms, galcanezumab 120 mg (with a loading dose of 240 mg) or 240 mg.37 Study CGAJ was designed to have fewer clinical research site visits, and patients were allowed to self-administer galcanezumab monthly while collecting outcome measures such as the Patient Satisfaction with Medication Questionnaire–Modified (PSMQ-M) questionnaire, HCRU, and acute medication use for migraine or headache. The objectives addressed in this research include the evaluation of changes during the 12-month treatment period compared with baseline, with respect to patient satisfaction with treatment, migraine-specific HCRU, and patterns of acute medication use for headache.

Methods

Study design

Study CGAJ (NCT02614287) was a 12-month, open-label study in patients with episodic or chronic migraine (Figure 1). This study was part of the phase 3 program of galcanezumab to assess long-term safety and provide longer term exposure data. Prior to the first study visit, patients were to have had a history of four or more MHDs per month on average for the past 3 months. Diagnosis of migraine was as defined by the International Headache Society (IHS) International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD)-3 beta version.38 Patients were excluded from the study if they had a history of headache other than migraine, tension-type headache, or medication overuse headache, as defined by IHS ICHD-3 beta within 3 months prior to randomization. Patients were also excluded if they were undergoing current treatment with preventive migraine medication.

Patients who met all criteria for enrollment were randomized 1:1 at Visit 2 to receive subcutaneous injections of either galcanezumab 120 mg or galcanezumab 240 mg. Assignment of patients to treatment groups was determined by a computer-generated random sequence using an interactive web-response system. To achieve between-group balance for site factor, the randomization was stratified by site. Individuals were allowed to self-administer galcanezumab starting at the second dosing visit; therefore, the study consisted of a mix of office visits and telephone visits. Patients assigned to galcanezumab 120 mg dose group received a loading dose of galcanezumab 240 mg at the first injection only (Figure 1).

Treatment compliance was defined as the number of completed scheduled dosing visits in which the patient received the assigned injections divided by the number of completed scheduled dosing visits, including any skipped dosing visits before Visit 14 or early discontinuation visit. Results from the 12-month, open-label treatment period are presented here. Twenty-eight clinical sites located in five countries, namely the US, Canada, Hungary, Belgium, and France, participated in the study.

The following Ethical Review Boards approved the study in their respective countries: Quorum Review, Inc., in the US, Commissie Medische Ethiek Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel in Belgium, IRB Services and Conjoint Medical Ethics Committee in Canada, CPP Sud Mediterannée V in France, and Egeszsegugyi Tudomanyos Tanacs in Hungary. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to their participation in the study.

Patient satisfaction with medication

The study used a self-rated five-point scale, called the PSMQ-M to measure satisfaction levels of patients. The scale was modified for use in this study and assessed the following three items related to galcanezumab over the previous 4 weeks: satisfaction, preference, and side effects.39 Satisfaction responses ranged from “very unsatisfied” to “very satisfied” with the current treatment. Preference compared the current study medication with previous medications, with responses that ranged from “much rather prefer my previous medication” to “much rather prefer the medication administered to me during the study.” Responses to question on side effects with current study medication versus previous medications for migraine prevention ranged from “significantly less side-effects” to “significantly more side-effects.” The responses to the questionnaire were solicited at Visits 4, 9, 15, and at early termination, if any (Figure 1).

Health care resource utilization

Study personnel solicited migraine-specific HCRU information at each monthly visit during treatment period and at months 14 and 16 during post-treatment period (Figure 1). The survey questions addressed outpatient health care professional visits, emergency room visits, and hospital admissions that occurred since the person’s last study visit. Duration of hospital stays was also captured; however, it is not reported due to the small number of admission events. Clinical site personnel and patients were instructed to capture utilization that was outside of visits associated with their participation in the clinical trial. The baseline visit included the same questions; however, the period of reference was the last 6 months (Supplementary materials, Health care resource utilization questions).

Acute medication use

Acute medication use for migraine or headache for the past month was collected at each office/phone visit (Visit 2 onwards) by direct questioning by the study investigator or designated site personnel. Information was collected for the following open-ended question: “How many days did the subject take any pain medication for migraine or headache in the past 30 days?”

Statistical analyses

Analyses to assess acute medication use and migraine-specific HCRU were conducted on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included data from all randomized people who received at least one dose of study drug. Change from baseline in number of MHDs per month as well as acute medication use for migraine or headache was analyzed using a mixed model with repeated measures analysis using all the longitudinal observations at each postbaseline visit. For each PSMQ-M item, the number and percentage of patients for each response were summarized by visit. For HCRU, summary statistics including number of persons with at least one event and HCRU events per 100 patient-years were calculated. Data from Visits 4 to 9 (Months 1 to 6) and from Visits 10 to 15 (Months 7 to 12) were added to provide a single number for the two 6-month periods. The number of events per 100 person-years for baseline and treatment periods was also calculated; only months when persons were enrolled in the study contributed to this analysis. Statistical comparisons of changes from baseline in HCRU per 100 patient-years were performed based on individual exposure-adjusted HCRU using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (for within-treatment group comparisons) or a Kruskal–Wallis test (for between-treatment group comparisons).

Results

Patient disposition and demographics

A total of 270 patients received at least one dose of galcanezumab 120 mg or galcanezumab 240 mg in a randomized fashion and were included as part of the analysis. The population was predominantly female (82.6%) and white (78.2%). Approximately 79% patients had a diagnosis of episodic migraine. The mean age was 42.0 years. Individuals in the galcanezumab 240 mg dose group were significantly older compared with the galcanezumab 120 mg dose group (mean age: 43.7 versus 40.2 years, respectively). Furthermore, at baseline, patients in the 240 mg dose group had significantly greater number of MHDs compared with the 120 mg dose group (11.4 versus 9.7 days per month). Otherwise, characteristics of age, sex, race, and body mass index were balanced across the dose groups. Patients had been diagnosed with migraine for an average of 20.7 years and had approximately 4.5 comorbid conditions (Table 1). The most common (≥10%) preexisting conditions (non-migraine) were depression, seasonal allergy, drug hypersensitivity, back pain, insomnia, anxiety, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. No patient reported acute medication overuse headache as a preexisting condition. A majority of individuals reported prior preventive treatment use (62.6%), with 21.1% of individuals having failed two or more preventives in the previous 5 years. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) total score and Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MSQ) Role Function-Restrictive scores (RF-R) in the study were 49.9 and 47.5, respectively, which indicated very severe disability (Table 1). In the galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg dose groups, 71.9% and 83.7% of patients completed the open-label treatment phase of the study, respectively. Mean treatment compliance was 95.8% and 96.9% over 12 months in the galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg dose groups, respectively.

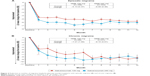

Reduction in migraine headache days with galcanezumab

During the 12-month open-label treatment phase, in both galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg dose groups, there were statistically significant within-group reductions from baseline in mean number of MHDs at each month. The overall mean reductions from baseline in number of monthly MHDs averaged over the 12-month, open-label treatment phase were 5.6 days and 6.5 days in galcanezumab 120 mg and galcanezumab 240 mg dose groups, respectively. There were statistically significant reductions from baseline in mean number of monthly MHDs of each month in patients with episodic migraine and in patients with chronic migraine. The overall mean reductions in number of monthly MHDs in the galcanezumab 120 mg and galcanezumab 240 mg groups were 5.1 days and 6.1 days in patients with episodic migraine and 7.2 days and 8.2 days in patients with chronic migraine, respectively (Figure 2).

Patient satisfaction, preference, and side effects with galcanezumab

At each of the three visits at months 1, 6, and 12 when assessments were made, at least 69% of patients responded positively on preference over prior treatments, overall study medication satisfaction, and less impact from side effects. Among patients who completed the 12-month treatment period, percentage of patients with a positive response increased over time from month 1 to month 12. Overall satisfaction with study medication increased from 70.1% to 74.8%, preference for the study treatment versus previous medications increased from 73.5% to 84.7%, and positive responses for side effects with galcanezumab compared with prior treatments increased from 71.2% to 81.2%. Furthermore, the percentage of patients reporting the higher level of positive responses (very satisfied with study medication, much prefer study medication, and much less side effects) increased from month 1 through month 6 and month 12 (Table 2). There were no meaningful differences between the two galcanezumab dose groups in percentage of patients with positive responses to the questionnaire (Supplementary materials, Table S1).

Reductions in health care resource utilization

In both the galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg dose groups, when compared with baseline, the percentage of patients with at least one migraine-related HCRU event was less during the treatment periods of Months 1 to 6 and Months 7 to 12. For health care professional visits, emergency room visits, and hospital admissions, percentages declined from 34.7%, 7.0%, and 1.5% (baseline) to 9.4%, 1.5%, and 0% (Months 1 to 6) and 8.2%, 1.7%, and 0.4% (Months 7 to 12), respectively (Figure 3A). When considering migraine-specific HCRU as rates per 100 person-years, health care professional visits declined from 173.4 to 59.6 visits, emergency room visits declined from 20.2 to 4.7, and hospital admissions declined from 3.7 to 0.4. In the analysis of HCRU as per 100 patient-years, there were statistically significant reductions (p<0.0001) in health care professional visits in galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg dose groups and in emergency visits in the galcanezumab 240 mg dose group (p<0.01). Reductions in emergency visits approached statistical significance in the galcanezumab 120 mg dose group (p=0.051) (Figure 3B). Overall, in both the analyses, there were no meaningful differences between the two galcanezumab doses in the level of reductions in any of the HCRU measures.

Reductions in acute medication use

At baseline, the mean (SD) number of days per month with acute medication use for migraine or headache was 9.84 (6.58) in galcanezumab 120 mg and 10.87 (7.16) in 240 mg dose groups, and 10.36 (6.89) overall. In both galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg dose groups, significant within-group reductions (p<0.001) from baseline in mean number of monthly MHDs with acute medication use were observed as early from month 1 which continued through month 12 (Figure 4). At month 1, mean reductions from baseline were 4.8 days and 4.0 days with galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg, respectively. There was a trend of increasingly higher reductions from baseline as the study progressed; at month 12, mean reductions from baseline were 5.3 days and 5.1 days with galcanezumab 120 mg and 240 mg, respectively. The overall mean reduction in number of monthly MHDs with acute medication use in the study was ~5.1 days (p<0.001) with both the galcanezumab doses (Figure 4). There were no meaningful differences between galcanezumab doses in mean reductions from baseline for both overall and monthly data.

Discussion

Galcanezumab belongs to a novel class of molecules specifically designed for migraine prevention.31 Therefore, it is important to evaluate the level of patient satisfaction and treatment preference with galcanezumab compared with prior treatments for migraine prevention. It is also important to assess the impact of this class of molecules on HCRU and acute medication use. Study CGAJ was a randomized, open-label, 12-month study where people with episodic or chronic migraine received galcanezumab 120 mg or 240 mg monthly.37 There were statistically significant and meaningful within-group reductions from baseline in mean number of MHDs/month at each month in the overall population, as well as in patients with chronic and episodic migraine. Treatment with galcanezumab led to high levels of satisfaction with current treatment and high levels of preference and less side effects versus previous treatments at Months 1, 6, and 12 in this study. There were meaningful reductions in migraine-specific HCRU (per 100 patient-years) from baseline during treatment period with galcanezumab for health care professional visits (173.4 to 59.6), emergency room visits (20.2 to 4.7), and hospital admissions (3.7 to 0.4). There were also significant and meaningful decreases in acute headache medication use from baseline at each monthly visit during the 12-month treatment period (overall change from baseline: −5.1 days). There were no meaningful differences between galcanezumab doses for any of the above outcomes.

The findings from this open-label, long-term study where patients were allowed to self-administer are reflective of clinical practice. The findings are important given the underutilization and high discontinuation rates associated with current standard of care for migraine prevention, namely oral daily medications.18,21 Research has demonstrated that the current standard of care for migraine prevention has the potential to reduce the burden of migraine, including HCRU.40 However, patients treated with the current standard of care are at risk of not experiencing meaningful reductions in migraine attack frequency or other outcomes due to difficulty tolerating their medication, resulting in substantial levels of early discontinuations.21 Patients with migraine rate efficacy as the most highly preferred attribute of a preventive; however, treatment goals are left unmet when a medication needs to be discontinued due to tolerability issues.41 A systematic review of randomized clinical trials and observational research studies reported high rates of discontinuation, low adherence, and low persistence with common migraine preventive medications. Discontinuation rates in clinical studies range from 23% to 45% for commonly used migraine preventives over a 4- to 6-month period (propranolol: 23%, topiramate: 43%, and amitriptyline: 45%).42 Observational studies suggest that commonly prescribed migraine preventives are associated with 7% to 55% persistence rates and 35% to 56% adherence rates over a period of 12 months.42 Compliance with oral standard of care measured by mean medication possession ratio is low with majority of patients filling only two or less prescriptions for their initial treatment.22 The authors note that this trend is concerning given the accepted view that preventive medications should be used for 2 to 3 months to ascertain effectiveness and relatively few patients may remain adherent over this timescale.22

It is important that future pharmaceutical interventions for migraine prevention address patient preferences, including desired levels of efficacy with fewer side effects and a low frequency of dosing schedule.41 The research reported here for galcanezumab addressed discontinuation rates related to adverse events and a lack of efficacy. Discontinuation rates were low over 12 months (<15%), and compliance with monthly subcutaneous injections among patients who completed the study was high (>95%). In addition, at month 12, patient self-reports of treatment satisfaction levels were 75%. Furthermore, 85% and 82% of patients reported preference for and less side effects with galcanezumab versus their previous treatments.

When patients with migraine who are in need of a preventive discontinue treatment, they rely solely on acute treatments. This can lead to unnecessary HCRU and medication overuse, which puts these patients at risk of disease progression.12–15 Research has indicated that following the initiation of migraine preventive treatment, reductions in mean annualized rates of acute treatments such as triptans range from 18.6% to 38.5%.43 In Study CGAJ, number of days with acute medication use for migraine or headache was reduced by more than 50% from baseline. When considering HCRU, research using the US claims database indicates that inpatient stays are uncommon for migraine. However, inpatient stays are higher before initiation of a new preventive versus after initiation in patients with previous experience of a preventive (2.4% vs 1.1%) and in patients with no experience (3.0% vs 0.4%).44 The prevalence of migraine-related emergency room visits was also higher during the preindex vs postindex period for patients with preventive therapy experience (14.4% vs 9.9%) and patients without (11.7% vs 7.1%).44 In Study CGAJ, both inpatient admissions and emergency department utilization specific to migraine decreased after initiation of galcanezumab from baseline: from 1.5% to 0.0% (Months 7 to 12) and from 7% to 1.7% (Months 7 to 12). Galcanezumab was designed for migraine prevention, and results from this study suggest that treatment with galcanezumab leads to approximately 50% reductions in acute medication use and preliminary evidence of reductions in HCRU.

This was an open-label clinical trial and was not designed to assess the magnitude of improvement versus a comparator, and therefore, causality cannot be inferred from results. Other confounding variables may have contributed to the study findings. The small sample size may have led to wider confidence intervals for estimated within-group improvements. Furthermore, the trial was conducted in a limited number of countries and so, the results may not be generalizable to patients and use within health care systems of various countries. This study was designed to specifically address safety objectives and was not powered to specifically address changes in HCRU. Strengths include that clinical site visits in the study were less frequent and patients were allowed to administer the drug independently in the home setting on a monthly basis. Patient satisfaction with treatment was self-reported on a measure that only assessed three attributes of treatment: satisfaction, preference, and side effects. HCRU was captured on a monthly basis, however, at baseline, patients had to recall utilization for the past 6 months. HCRU that is collected with a 6-month recall is more likely to be underreported or accurately reported than overreported (75% vs 25%).45 Research using a 6-month recall found that self-reported physician visits tend to be underreported particularly among patients with chronic conditions and higher utilization.46 Both emergency room visits and hospitalizations have low discrepancy with a 6-month recall, with slight overestimation among patients with higher utilization; however, self-report may provide greater accuracy compared with the utilization captured in a health maintenance organization database system due to associated out-of-network events, which are more likely to occur in the subgroup with higher utilization.46 Specific acute medication use was not captured in a daily log but rather recorded on an as-needed basis in the concomitant medication form; therefore, acute medications taken on a daily basis cannot be further broken out by class and this is a limitation.

In conclusion, this open-label 12-month study provides insight into patient preferences, compliance with treatment, acute medication use, and HCRU reductions for galcanezumab in patients with migraine. More research is needed, particularly in typical clinical practice settings across various geographies; however, the limited site-visit design with self-injections at home indicates the potential for low discontinuation and high compliance with positive outcomes. The observed reductions in acute medication use are likely to lead to decreases in the risk of medication overuse and disease progression in patients with migraine, while also reducing the burden related to health care utilization. Unlike the currently available standard of care, which has high discontinuation rates that limit clinicians’ and patients’ abilities to achieve desired treatment goals, galcanezumab is a pharmaceutical intervention designed specifically for the treatment of migraine. Overall, in this study, patient satisfaction and preference measures were high for galcanezumab, and side effects were identified as being lower versus previously used preventives. The efficacy, dosing regimen, and safety/tolerability profile of galcanezumab have the potential to improve health outcomes among patients with migraine who are in need of a preventive treatment.

Data sharing statement

Eli Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available on request in a timely fashion after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once they are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank, or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment for up to 2 years per proposal. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA. Sriram Govindan, an employee of Eli Lilly Services India Private Limited, Bengaluru, India, provided writing assistance.

Author contributions

JHF contributed to study concept, design, analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting manuscript; SAF to design, analysis, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; VLS to study concept, design, analysis, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; DDR to design, analysis, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; SKA to interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content; and JV to acquisition and interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

JHF, SAF, VLS, DDR, and SKA are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company and/or one of its subsidiaries and may hold company stocks. JV received personal fees and nonfinancial support from Teva, personal fees from Novartis, and grants and nonfinancial support from Allergan. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Dodick DW. Migraine. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1315–1330. | ||

Lipton RB, Silberstein SD. Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache. 2015;55(Suppl 2):103–122; quiz 123–126. | ||

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edn. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. | ||

Merikangas KR. Contributions of epidemiology to our understanding of migraine. Headache. 2013;53(2):230–246. | ||

GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1545–1602. | ||

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. | ||

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349. | ||

World Health Organization (WHO). Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011: a collaborative project of World Health Organization and lifting the burden. 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2018. | ||

Worthington I, Pringsheim T, Gawel MJ, et al. Canadian Headache Society Guideline: acute drug therapy for migraine headache. Can J Neurol Sci. 2013;40(5 Suppl 3):S1–S3. | ||

Freitag FG, Schloemer F. Medical management of adult headache. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47(2):221–237. | ||

Weatherall MW. The diagnosis and treatment of chronic migraine. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(3):115–123. | ||

Lanteri-Minet M. Economic burden and costs of chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18(1):385. | ||

Valade D, Lucas C, Calvel L, et al. Migraine diagnosis and management in general emergency departments in France. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(4):471–480. | ||

Friedman BW. Managing migraine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(2):202–207. | ||

Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301–315. | ||

Schwedt TJ. Chronic migraine. BMJ. 2014;348:g1416. | ||

Pike J, Mutebi A, Shah N, et al. Factors associated with a history of failure and switching migraine prophylaxis treatment: an analysis of clinical practice data from the United States, Germany, France, and Japan. Value Health. 2016;19(3):A68. | ||

Rizzoli P. Preventive pharmacotherapy in migraine. Headache. 2014;54(2):364–369. | ||

Vanderpluym J, Evans RW, Starling AJ. Long-term use and safety of migraine preventive medications. Headache. 2016;56(8):1335–1343. | ||

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470–485. | ||

Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–655. | ||

Berger A, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, Oster G. Adherence with migraine prophylaxis in clinical practice. Pain Pract. 2012;12(7):541–549. | ||

Woolley JM, Bonafede MM, Maiese BA, Lenz RA. Migraine prophylaxis and acute treatment patterns among commercially insured patients in the United States. Headache. 2017;57(9):1399–1408. | ||

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):478–488. | ||

Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and migraine progression. Neurology. 2008;71(22):1821–1828. | ||

Lipton RB, Serrano D, Nicholson RA, Buse DC, Runken MC, Reed ML. Impact of NSAID and Triptan use on developing chronic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2013;53(10):1548–1563. | ||

Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(1):86–92. | ||

Abu Bakar N, Tanprawate S, Lambru G, Torkamani M, Jahanshahi M, Matharu M. Quality of life in primary headache disorders: a review. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(1):67–91. | ||

Messali A, Sanderson JC, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Direct and indirect costs of chronic and episodic migraine in the United States: a web-based survey. Headache. 2016;56(2):306–322. | ||

Shah AM, Bendtsen L, Zeeberg P, Jensen RH. Reduction of medication costs after detoxification for medication-overuse headache. Headache. 2013;53(4):665–672. | ||

Tso AR, Goadsby PJ. Anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies: the next era of migraine prevention? Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017;19(8):27. | ||

Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Spierings EL, Scherer JC, Sweeney SP, Grayzel DS. Safety and efficacy of LY2951742, a monoclonal antibody to calcitonin gene-related peptide, for the prevention of migraine: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(9):885–892. | ||

Skljarevski V, Oakes TM, Zhang Q, et al. Effect of different doses of galcanezumab vs placebo for episodic migraine prevention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(2):187–193. | ||

Skljarevski V, Matharu M, Millen BA, Ossipov MH, Kim BK, Yang JY. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 Phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(8):1442–1454. | ||

Stauffer VL, Dodick DW, Zhang Q, Carter JN, Ailani J, Conley RR. Evaluation of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: the EVOLVE-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1080–1088. | ||

Detke H, Wang S, Skljarevski V, et al. A phase 3 placebo-controlled study of galcanezumab in patients with chronic migraine: results from the 3-month double-blind treatment phase of the REGAIN Study. PO-01-195. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(IS):319. | ||

Stauffer VL, Sides R, Camporeale A, Skljarevski V, Ahl J, Aurora SK. A Phase 3, long-term, open-label safety study of self-administered galcanezumab injections in patients with migraine. (PO-01-184). Cephalalgia. 2017;37(IS):319. | ||

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808. | ||

Kalali A. Patient satisfaction with, and acceptability of, atypical antipsychotics. Curr Med Res Opin. 1999;15(2):135–137. | ||

Wu J, Hughes MD, Hudson MF, Wagner PJ. Antimigraine medication use and associated health care costs in employed patients. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(2):121–127. | ||

Peres MF, Silberstein S, Moreira F, et al. Patients’ preference for migraine preventive therapy. Headache. 2007;47(4):540–545. | ||

Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(1):22–33. | ||

Yaldo AZ, Wertz DA, Rupnow MF, Quimbo RM. Persistence with migraine prophylactic treatment and acute migraine medication utilization in the managed care setting. Clin Ther. 2008;30(12):2452–2460. | ||

Bonafede M, Sapra S, Tepper SJ, Cappell KA, Desai P. Healthcare costs and utilization and medication treatment patterns among migraine patients: a retrospective analysis. PS58. Headache. 2017; 57 (S3. Special Issue: Program Abstracts: The 59th Annual American Headache Society Meeting):113–226. | ||

Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):217–235. | ||

Ritter PL, Stewart AL, Kaymaz H, Sobel DS, Block DA, Lorig KR. Self-reports of health care utilization compared to provider records. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(2):136–141. |

Supplementary materials

Health care resource utilization questions

- Since your last visit, did you go to a hospital emergency room for medical care? _____Yes _____No

- If yes, how many times did you go to a to a hospital emergency room? ______

- How many of these times going to a hospital emergency room were related to your migraine headaches? _______

- Since your last visit, were you a patient in a hospital overnight? _____Yes _____No

- If yes, how many different times were you a patient in a hospital overnight? _______

➢ How many days in total were you in the hospital for overnight stays? _______ - How many of these times, as a patient in a hospital overnight, were related to your migraine headaches? _______

- How many days in total, as a patient in a hospital overnight, were related to your migraine headaches? _______

- If yes, how many different times were you a patient in a hospital overnight? _______

- Since your last visit, did you have any other visits with a healthcare professional of any kind (physician of any specialty, nurse, rehabilitation specialist, physical therapist, psychologist, or counselor, urgent care center, etc.)? _____Yes _____No

- If yes, how many different times did you visit a healthcare professional? _______

- How many of these times, visiting a healthcare professional, were related to your migraine headaches? _______

[For baseline (visit 2) = “In the last 6 months” instead of “since your last visit”]

| Table S1 Breakdown of responses to the Patient Satisfaction with Medication Questionnaire–Modified by galcanezumab dose group and visit |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.