Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 12

Patient preferences for important attributes of bipolar depression treatments: a discrete choice experiment

Authors Ng-Mak D, Poon JL, Roberts L, Kleinman L, Revicki DA, Rajagopalan K

Received 13 September 2017

Accepted for publication 11 December 2017

Published 28 December 2017 Volume 2018:12 Pages 35—44

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S151561

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Daisy Ng-Mak,1 Jiat-Ling Poon,2 Laurie Roberts,2 Leah Kleinman,2 Dennis A Revicki,2 Krithika Rajagopalan1

1Global Health Economics and Outcomes Research, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Marlborough, MA, 2Patient-Centered Research, Evidera, Bethesda, MD, USA

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess patient preferences regarding pharmacological treatment attributes for bipolar depression using a discrete choice experiment (DCE).

Methods: Adult members of an Internet survey panel with a self-reported diagnosis of bipolar depression were invited via e-mail to participate in a web-based DCE survey. Participants were asked to choose between hypothetical medication alternatives defined by attributes and levels that were varied systematically. The six treatment attributes included in the DCE were time to improvement, risk of becoming manic, weight gain, risk of sedation, increased blood sugar, and increased cholesterol. Attributes were supported by literature review, expert input, and results of focus groups with patients. Sawtooth CBC System for Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis was used to estimate the part-worth utilities for the DCE analyses.

Results: The analytical sample included 185 participants (50.8% females) from a total of 200 participants. The DCE analyses found weight gain to be the most important treatment attribute (relative importance =49.6%), followed by risk of sedation (20.2%), risk of mania (13.0%), increased blood sugar (8.3%), increased cholesterol (5.2%), and time to improvement (3.7%).

Conclusion: Results from this DCE suggest that adults with bipolar depression considered risks of weight gain and sedation associated with pharmacotherapy as the most important attributes for the treatment of bipolar depression. Incorporating patient preferences in the treatment decision-making process may potentially have an impact on treatment adherence and satisfaction and, ultimately, patient outcomes.

Keywords: bipolar depression, treatment preference, adverse events, weight gain

Introduction

Bipolar I disorder is characterized by periods of severe mood episodes that fluctuate between clinical depression, mania, and mixed episodes and are associated with significant disability and functional impairment.1 In the US, the lifetime prevalence of bipolar I disorder is 1%, with a 12-month prevalence of 0.6%.2 Patients diagnosed with bipolar I disorder have been found to experience depressive symptoms three times more often than manic symptoms.3,4 Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder (ie, bipolar depression) tend to last longer, occur more frequently, and are associated with higher suicide rates and work-related disability compared to manic episodes.5

Although several treatment options are available for the management of bipolar I disorder, there are currently only three US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved atypical antipsychotic treatments for bipolar depression: quetiapine, olanzapine in combination with fluoxetine, and lurasidone.6 These medications have also received regulatory approval for the treatment of bipolar depression in other localities such as Canada (lurasidone and quetiapine), the European Union (quetiapine), and Japan (olanzapine). As a class, atypical antipsychotics have unique efficacy and tolerability profiles but are usually associated with considerable adverse effects, including weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.7

Approximately 60% of patients with bipolar disorder do not sufficiently adhere to their medication.8–11 According to a recent systematic literature review of observational studies, one of the most commonly reported reasons for medication nonadherence in bipolar disorder is adverse effects of treatment, such as weight gain, sedation, tremors, and perceived cognitive impairment.12,13 In addition, residual depressive symptoms may also negatively impact medication adherence.14 Using a stated-preference approach, side effects of weight gain or cognitive impairment were similarly identified as major considerations for the treatment of nonadherence in bipolar disorder.15 The management of bipolar disorder includes proactive monitoring of these adverse effects, such as weight gain, through encouragement of lifestyle and behavioral modifications.16

Treatment nonadherence in bipolar disorder remains a continuous challenge with both clinical and economic consequences.8,11,17 Nonadherence is associated with decreased treatment effectiveness, increased relapses, escalated morbidity, and increased hospitalizations and other health care utilization,8,11,17 which can lead to higher health care costs and decreased quality of life. Identifying patient treatment preferences by allowing patients to trade-off the benefits and risks associated with the treatment of bipolar depression may lead to a better understanding of the patients’ perspective for both physicians and patients and, ultimately, increase medication adherence rates.18

One way to assess patient preferences is to conduct a discrete choice experiment (DCE), a methodology that resembles real-life decision making.19 In a DCE, participants are asked to choose between scenarios describing realistic treatment options and where they make trade-offs between different treatment attributes. This differs from a survey-only approach where patients may be asked to answer questions about independent treatment features, including side effects, without taking into account the trade-offs required to choose between multiple treatment characteristics at once.

A few published studies of DCEs were conducted in mental health populations. However, a previous research has found that patients with severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia or major depressive disorder, may be able to appropriately complete DCE tasks and make meaningful decisions about preferred treatment scenarios based on different attributes.19 DCE methodology has previously been used in a bipolar disorder population to assess factors associated with nonadherence to treatment. The results demonstrated that patients were more likely to be adherent to medications if they reduced the severity of their depressive episodes and did not cause weight gain or cognitive side effects.15 However, this prior work did not focus on bipolar depression.

The objective of this study was to assess patient preferences regarding pharmacological treatment attributes for bipolar depression via a DCE.20

Methods

The DCE involved a series of systematic steps, including 1) development of treatment attributes, and 2) implementation of the DCE. All study activities were conducted in English.

Development of treatment attributes

Relevant treatment attributes and conceptualizations of treatment scenarios were developed through literature reviews and focus groups. A targeted literature review of articles that described bipolar depression treatments and a review of recent product inserts were conducted. PubMed and Embase were used to conduct the literature search, and the search strategies are included as a supplement to the manuscript. Product inserts for 29 medications used to manage bipolar disorder/depression were reviewed, including nine typical antipsychotics, 12 atypical antipsychotics, seven anticonvulsants, and lithium. Information related to dosing characteristics, need for monitoring, efficacy (eg, time to improvement, remission rates), adherence rates, and common adverse events was extracted from these review sources.

Following the literature review, one expert clinician interview and two focus groups with 16 adult patients21 were conducted. The purpose of the expert interview was to draw on the clinician’s experiences to identify key issues and concerns in bipolar depression, with a greater emphasis on treatment side effects and reasons for continuing or discontinuing treatment. The interview was conducted using a semi-structured interview guide.

The focus groups enrolled adult participants from two clinical sites in the US (n=8 per site). All focus group participants had a clinician-confirmed diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, a history of ≥1 major depressive episode within the last 12 months, a lifetime history of ≥1 manic or mixed manic episode, and currently or previously received antipsychotic drug therapy for bipolar disorder. Mean age of focus group participants was 47.9 years (SD =6.0 years), and 69% were females. Mean time since the participants’ initial bipolar I disorder diagnosis was 15.7 years (SD =11.4 years), and their mean duration of atypical antipsychotic use was 4.9 years (SD =4.7 years). The focus groups were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide to elicit information regarding expectations of treatment, treatment experiences, and potential barriers to treatment for bipolar depression. Audio recordings of the focus groups were transcribed and analyzed for themes that patients described as being related to their expectations and preferences for bipolar depression treatment using ATLAS.ti (version 7.5.3).

The most important medication attributes identified from the expert clinician interview and patient focus groups are given in Table 1. Efficacy and weight gain were reported as important treatment attributes for patients with bipolar depression. Patients also defined “time to improvement” as the time from treatment initiation to when they began to observe improvements in their symptoms. Findings from the qualitative research were used to determine the relevant attributes and attribute levels for the DCE scenarios to be used in the pilot and main DCE studies. In determining the final list of attributes, greater emphasis was placed on factors identified by patients as being important in influencing their treatment decisions. Levels of attributes were determined based on results of clinical trials reported in the product inserts, including incidence rates of each event and time to improvement of depressive symptoms.

| Table 1 Important medication attributes for the treatment of bipolar depression identified via interviewsa |

Implementation of DCE

The DCE was implemented via a one-time, cross-sectional, web-based survey. Prior to full implementation, one-on-one pilot interviews were conducted via web conference.

Participants

For the pilot and main web-based surveys, members of MedPanel,22 an Internet survey panel, with self-reported bipolar depression were invited via e-mail to participate. MedPanel specializes in the life science industry and maintains a large patient panel across various diseases, including bipolar disorder. MedPanel members were originally recruited through patient associations, patient support groups, and physician referrals. Interested patients answered a series of screening questions to determine study eligibility.

Inclusion criteria were adult subjects (18–75 years), self-reported diagnosis of bipolar depression (bipolar I disorder with most recently documented depressive episode within the last 12 months), lifetime history of ≥1 manic or mixed manic episode, and currently or previously received antipsychotic drug therapy for bipolar disorder. Exclusion criteria were hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode within the 60 days prior to screening, participation in any other clinical trial, or had received study medication ≤45 days from study screening. Diagnosis of bipolar depression was self-reported by patients, and symptoms of depression were further verified through patients’ responses to screening questions related to use of medications to manage bipolar disorder and symptoms of depression and/or mania.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from Ethical and Independent Review Services on October 16, 2015 (study number: 15127-01) for the study protocol and recruitment materials. All participants provided electronic informed consent, and each eligible participant received $20 for completing the study.

A pilot study with four participants was conducted using the preliminary DCE scenarios to assess the clarity and understanding of the web-based survey questions. Based on participants’ feedback, minor changes were made to the attribute names and the order of tasks. Participants understood the DCE task and were able to complete the web-based survey with minimal difficulty. The final treatment attributes and levels used for the DCE scenarios are given in Table 2. In the main DCE, eligible participants completed only the web-based survey.

| Table 2 Final DCE attributes and levels |

Survey instrument

Eligible participants were asked to complete up to 10 sets of DCE scenarios, sociodemographic and clinical questions, the self-reported Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS-S),23,24 the WHO-5 Well-Being Index (WHO-5),25 and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health Instrument (GHI).26

In each DCE scenario, two hypothetical bipolar depression medications comprising different attributes (time to improvement, risk of becoming manic, weight gain, risk of sedation, increased blood sugar, and increased cholesterol) and corresponding levels for each attribute were presented (Table 2 and Figure 1). Participants were instructed to review the treatment pairings and select the medication they would prefer to take at the present time given the options. Each participant responded to only 10 choice pairs in order to both minimize the cognitive burden on participants and maximize the efficiency of the study design, given the number of attributes and levels included in the DCE. One of the discrete choice scenarios presented was a fixed-choice question and was not included in the final analysis. The fixed-choice question presented a clearly favorable medication choice to establish that participants understood the DCE task. Those who responded incorrectly were excluded from the analysis. To prevent potential biases in responses, the fixed-choice question was presented as part of the full set of scenarios. In addition to the discrete choice task, participants were also asked to directly rank the six attributes in order of importance on a scale of 1 (most important) to 6 (least important).

| Figure 1 DCE question sample. |

The MADRS-S is a nine-item self-report scale assessing depressive symptoms over the past 3 days.23,24 Patients were asked to rate the severity of each of the symptoms assessed on a scale ranging from 0 to 6. The total score for the MADRS-S was then calculated by summing the ratings of the nine items, which ranged between 0 and 54, with higher scores indicating greater impairment.

The WHO-5 is a measure of emotional well-being developed from the World Health Organization-Ten Well-Being Index25 and consists of five positively worded items assessing emotional well-being over the past 2 weeks. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not present) to 5 (constantly present). Individual item ratings are summed to obtain a raw score ranging from 0 (worst possible quality of life) to 25 (best possible quality of life), which may be transformed into a percentage score ranging from 0 (worst possible quality of life) to 100 (best possible quality of life). A raw score ≤13 has been found to be indicative of depression.

The PROMIS Global Health Questionnaire26 comprises 10 questions covering the global domains of physical health and mental health. Severity questions assess the respondent’s current state using a response scale of “excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor”. Frequency questions assess the past 7 days using a response scale of “never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always”.

Statistical analyses of DCE

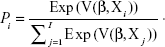

Descriptive analyses were conducted on sociodemographic and patient-reported outcome questionnaire data. For the DCE data, preference weights (part-worth utility values) were estimated using a random-effects multinomial logit model.27 The model estimated the probability of a patient choosing an alternative i (over a set of possible alternatives I in the given choice set) with the βs representing the estimated part-worth utilities.

|

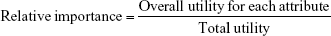

A positive part-worth utility indicated that the attribute level was preferred over levels with negative values, and larger part-worth utilities indicated a higher degree of preference for one level over another. The part-worth utilities were scaled to have a mean value of zero and then used to calculate the relative importance of each attribute. The relative importance of each attribute was then calculated using the following formula:

|

Overall utility value for each attribute equaled the range of part-worth utilities within each attribute, and total utility value equaled the sum of overall utility values across all attributes. The relative importance of each attribute was expressed as a percentage, reflecting the proportion of the variance in the overall medication decision that was accounted for by each attribute. Utilities and relative importance were evaluated for each DCE attribute. Sawtooth CBC System for Choice-Based Conjoint Analysis (version 7; Sawtooth Software, Inc., Provo, Utah, USA) was used to generate the DCE survey questions and to estimate the part-worth utilities for the DCE analyses. SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to conduct all other analyses.

Subgroup analyses

Participant preferences were stratified by gender and age (using a median split). The subgroups were determined based on a priori hypotheses that there may be gender differences in preferences for the attributes included in the DCE, especially weight gain. In addition, it was hypothesized that older patients may be diagnosed as bipolar for longer and have more experience with different bipolar medications, while younger patients may place a greater emphasis on attributes such as risk of sedation due to work or school productivity concerns. Relative importance was calculated separately for each age and gender subgroup. Chi-square tests were used to determine any significant differences in the relative importance of the attributes between subgroups.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 200 eligible participants provided informed consent and completed the main web-based DCE survey. In all, 11 (5.5%) participants provided an incorrect response to the fixed-choice question and four participants (2.0%) “straight-lined” their responses (ie, they selected the same response option for all questions, indicating that they may not have been making decisions but instead trying to complete the survey quickly); these participants were excluded from the analyses, resulting in 185 participants being included in the analytical sample.

Demographic and self-reported clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 3. The majority of the participants (88.6%) were currently receiving medication for bipolar depression, most commonly atypical antipsychotics (75.1%). Mean MADRS-S total score was 23.9 (SD =9.9), indicative of moderate depression, and mean WHO-5 raw score was 8.9 (SD =5.0), indicative of poor well-being. Physical health (T-score =39.1; SD =7.2) and mental health (T-score =35.6; SD =7.7) scores, as assessed by the PROMIS GHI, were lower than that of the general population (based on the standardized population mean of 50), also indicating poor health status.28

Relative importance weights for treatment attributes

The part-worth utility values are shown in Figure 2. The corresponding relative importance indicated that, in the context of the included attributes, participants considered weight gain as the most important attribute of a treatment (relative importance =49.6%; Figure 2). A treatment associated with less weight gain was preferred over a treatment associated with more weight gain. In the context of this study, the second-most important attribute was risk of sedation (relative importance =20.2%). Treatment associated with lower risk of sedation was preferred over treatment with more sedation. The remaining attributes, in order of relative importance, were risk of becoming manic, increased blood glucose, increased cholesterol, and time to improvement. Part-worth utilities were in the expected direction for the levels within each of these attributes, with greater preference for less severe adverse events and faster improvement.

Participant preferences were further stratified by gender and age (using the median split of ≤40 years [n=93] and >40 years [n=92]). Within each subgroup, the relative importance of each attribute in rank order was the same as that of the overall sample. Descriptively, females placed greater relative importance on weight gain (53.2%) than males (45.9%), while slightly greater relative importance was placed on all other attributes by males than by females. The attributes “increased cholesterol” and “time to improvement” were both fifth in relative importance in the >40 years subgroup. A chi-square test comparing relative importance between subgroups (male vs female, ≤40 years vs >40 years) found no statistically significant differences in the relative importance of each attribute across gender or age groups.

When asked to directly rank the six attributes included in the DCE in order of importance (1= most important; 6= least important), the participants ranked weight gain as the most important, with a mean rank of 2.4 (SD =1.6), followed by risk of becoming manic (mean rank =3.0 [SD =1.7]), time to improvement (mean rank =3.1 [SD =1.6]), risk of sedation (mean rank =3.7 [SD =1.7]), increased blood sugar (mean rank =4.2 [SD =1.4]), and increased cholesterol (mean rank =4.6 [SD =1.3]).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine patient preferences in the treatment of bipolar depression using a DCE methodology. In this DCE study, weight gain, risk of sedation, and risk of becoming manic were identified as the three most important attributes for adult participants with bipolar depression. In contrast, when time to improvement was considered alongside these side effects, it was ranked the least important. These findings were consistent across age and gender subgroups. While this study was not designed to assess factors that would increase patients’ adherence to treatment, it identified factors that patients consider important in influencing their treatment decisions. These factors can be used by health care providers as a starting point to initiate treatment discussions, and discussions around treatment adherence, with patients.

The importance of tolerability in influencing patient treatment preferences emerges as a consistent theme when examining the results of this study with other studies conducted in mental health populations using DCE methodology, including bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia.15,18,29–31 Consistent with the literature, our findings demonstrated that tolerability in general, and weight gain in particular, is an important treatment attribute for patients with bipolar disorder or bipolar depression.16,32,33 As weight gain among patients taking atypical antipsychotics is a major concern, a personalized treatment with a relatively lower risk of weight gain may increase treatment adherence and thereby improve patient outcomes.32,33

Risk of sedation was identified as the second most important treatment attribute of this study. As study participants were generally younger, they may be more concerned about bipolar depression treatments with sedative effects, which might impair normal activities of daily living and work productivity. Research suggests that sedation may not only have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life, and social and occupational functioning, it can also cause impaired cognitive and motor functioning,34 which might heighten the risk of accidents.35 Not surprisingly, Mago et al13 identified risk of sedation as a reason for treatment discontinuation in up to 30% of bipolar disorder patients. In addition, sedation and weight gain were identified as the most likely adverse effects that may lead to nonadherence in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Unique to patients with bipolar depression, the risk of becoming manic was identified as the third most important treatment attribute of this study. Monotherapy with an antidepressant may increase the risk of mania or rapid cycling without demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of bipolar depression.15,16,36 One in five participants of this study had used antidepressants as treatment for bipolar depression. It is possible that prior experiences with, or knowledge of, treatment-induced manic episodes may be a reasonable concern for patients with bipolar depression in selecting an appropriate treatment.

Efficacy, measured in time to improvement, was identified as the least important treatment attribute in the context of this DCE study. In contrast to the DCE, the direct ranking exercise in the web-based survey, the clinician interview and patient focus groups considered “time to improvement” as one of the three top important attributes. The apparent discrepancy between the DCE and the absolute rank task and qualitative research may be due to the range of levels provided in the DCE and the lack of context provided in the ranking task. All three levels of the time to improvement treatment attribute (within 1, 2, or 4 weeks) might have been within the treatment expectations of participants in the DCE study. Registration trials of FDA-approved drugs for acute treatment of bipolar depression were conducted over 6 and 8 weeks for lurasidone37,38 and quetiapine,39,40 respectively, using change from baseline of MADRS scores as the primary end point. Significantly greater mean improvements in MADRS for treatment compared to placebo were observed as early as week 1. In contrast, the time to improvement in the ranking exercise did not specify the range of time for improvement, and participants ranked each attribute independently of the others, without having to make trade-offs between attributes and their levels of importance. If the range of levels for the time to improvement in the DCE had included a more extended time period to improvement, time to improvement may have been identified as relatively more important.

Limitations

As with all studies using the DCE methodology, the results of this study should be interpreted within the context of the limited attributes and levels that were included in the study design. While the selection of the attributes and levels were based on prior literature review and qualitative research, in order to reduce respondent burden, only the most important and relevant attributes were included in the final discrete choice task. Thus, the extent to which preferences expressed in the context of this experiment represent real-life choices is unknown. Medication cost was not included as a treatment attribute; therefore, the extent to which cost may have affected treatment choice is unknown. Patients were recruited via a web panel and provided a self-reported diagnosis of bipolar depression. Patients’ willingness to participate in a web survey may pose as a potential selection bias, which may limit the representativeness of the overall bipolar population. However, this method of recruitment is not uncommon in studies with similar designs, including in mental health.15,29 This study was conducted only in English in the US and thus may not be generalizable to the US non-English-speaking population. Subgroup analysis of preferences was not conducted based on bipolar depression severity as severity of illness was not assessed in the survey. This may be an interesting area for future research.

Conclusion

The results of this DCE study suggest that tolerability concerns such as risks of weight gain, sedation, and medication-induced mania were the most important factors for the treatment of bipolar depression from the patients’ perspective. Incorporating patients’ preferences in the treatment, decision-making process has the potential to improve treatment satisfaction, treatment adherence, and, ultimately, patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chien Chia Chuang of Vertex Pharmaceuticals for providing project management support for this project while working for Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Thomas Lee and Michael Stensland of Agile Outcomes Research, Inc. This research was funded by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the study conception and design, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Disclosure

DN-M and KR are full-time employees of Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. J-LP, LR, LK, and DAR are full-time employees of Evidera. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RM, Frye MA, Reed ML. Impact of depressive symptoms compared with manic symptoms in bipolar disorder: results of a U.S. community-based sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(11):1499–1504. | ||

Connolly KR, Thase ME. The clinical management of bipolar disorder: a review of evidence-based guidelines. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(4):10r01097. | ||

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530–537. | ||

Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241–251. | ||

Frye MA, Prieto ML, Bobo WV, et al. Current landscape, unmet needs, and future directions for treatment of bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(suppl 1):S17–S23. | ||

Nierenberg AA, McIntyre RS, Sachs GS. Improving outcomes in patients with bipolar depression: a comprehensive review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):e10. | ||

Ucok A, Gaebel W. Side effects of atypical antipsychotics: a brief overview. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):58–62. | ||

Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Benabarre A, Gasto C. Clinical factors associated with treatment noncompliance in euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(8):549–555. | ||

Greenhouse WJ, Meyer B, Johnson SL. Coping and medication adherence in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2000;59(3):237–241. | ||

Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(5):384–390. | ||

Vieta E. Improving treatment adherence in bipolar disorder through psychoeducation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 1):24–29. | ||

Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, Kramata P, Docherty JP. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449–468. | ||

Mago R, Borra D, Mahajan R. Role of adverse effects in medication nonadherence in bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):363–366. | ||

Belzeaux R, Correard N, Boyer L, et al; Fondamental Academic Centers of Expertise for Bipolar Disorders (FACE-BD) Collaborators. Depressive residual symptoms are associated with lower adherence to medication in bipolar patients without substance use disorder: results from the FACE-BD cohort. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):1009–1015. | ||

Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Manjunath R, Hauber AB, Burch SP, Thompson TR. Factors that affect adherence to bipolar disorder treatments: a stated-preference approach. Med Care. 2007;45(6):545–552. | ||

Kemp DE. Managing the side effects associated with commonly used treatments for bipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2014;169(suppl 1):S34–S44. | ||

Eaddy M, Grogg A, Locklear J. Assessment of compliance with antipsychotic treatment and resource utilization in a Medicaid population. Clin Ther. 2005;27(2):263–272. | ||

Wittink MN, Morales KH, Cary M, Gallo JJ, Bartels SJ. Towards personalizing treatment for depression: developing treatment values markers. Patient. 2013;6(1):35–43. | ||

Bridges JF, Kinter ET, Schmeding A, Rudolph I, Muhlbacher A. Can patients diagnosed with schizophrenia complete choice-based conjoint analysis tasks? Patient. 2011;4(4):267–275. | ||

Hauber AB, Gonzalez JM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–315. | ||

Ng-Mak DS, Rajagopalan K, Kleinman L, Roberts L, Revicki DA, Loebel A. Qualitative study of patients’ preferences for bipolar depression treatment. In: ISPOR 20th Annual International Meeting; May 16–20, 2015; Philadelphia, PA. | ||

MedPanel [homepage on the Internet]. Available from: www.medpanel.com. Accessed December 12, 2017. | ||

Cunningham JL, Wernroth L, von Knorring L, Berglund L, Ekselius L. Agreement between physicians’ and patients’ ratings on the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):148–153. | ||

Svanborg P, Asberg M. A comparison between the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). J Affect Disord. 2001;64(2–3): 203–216. | ||

Bech P. Clinical Psychometrics. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. | ||

Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873–880. | ||

Sawtooth Software Inc. The CBC/HB System for Hierarchical Bayes Estimation Version 5.0 Technical Paper. Sequim, WA: Sawtooth Software Inc.; 2009. | ||

Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al; PROMIS Cooperative Group. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. | ||

Levitan B, Markowitz M, Mohamed AF, et al. Patients’ preferences related to benefits, risks, and formulations of schizophrenia treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):719–726. | ||

Morey E, Thacher JA, Craighead WE. Patient preferences for depression treatment programs and willingness to pay for treatment. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2007;10(2):73–85. | ||

Wittink MN, Cary M, Tenhave T, Baron J, Gallo JJ. Towards patient-centered care for depression: conjoint methods to tailor treatment based on preferences. Patient. 2010;3(3):145–157. | ||

Berk M, Berk L, Castle D. A collaborative approach to the treatment alliance in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(6):504–518. | ||

Revicki DA, Hanlon J, Martin S, et al. Patient-based utilities for bipolar disorder-related health states. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2–3):203–210. | ||

Kane JM, Sharif ZA. Atypical antipsychotics: sedation versus efficacy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(suppl 1):18–31. | ||

Ramaekers JG. Behavioural toxicity of medicinal drugs. Practical consequences, incidence, management and avoidance. Drug Saf. 1998;18(3):189–208. | ||

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(1):1–44. | ||

Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):160–168. | ||

Loebel A, Cucchiaro J, Silva R, et al. Lurasidone as adjunctive therapy with lithium or valproate for the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(2):169–177. | ||

Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Macfadden W, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1351–1360. | ||

Thase ME, Macfadden W, Weisler RH, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the BOLDER II study). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):600–609. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.