Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

Patient considerations in the management of chronic constipation: focus on prucalopride

Authors Shin A

Received 24 February 2016

Accepted for publication 11 May 2016

Published 28 July 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 1373—1384

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S92550

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Andrea Shin

Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

Abstract: Chronic constipation is a common condition that significantly impacts health care utilization, productivity, and quality of life. Laxatives are commonly used, although often insufficient in restoring normal bowel function or providing adequate relief. There remains a significant need for the development of novel agents to optimize treatment of this condition. This review provides an overview of the preclinical and clinical trial data, supporting the efficacy and safety of prucalopride, a highly selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist that has been approved by the European Medicine Agency for the treatment of chronic constipation in adults who have failed standard laxative therapy. Unlike older 5-HT4 agonists, prucalopride has not been associated with adverse cardiovascular side effects or QT prolongation owing to its high selectivity and affinity for the 5-HT4 receptor without clinically significant cross-reactivity at the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel or 5-HT receptor subtypes that have previously been implicated in adverse cardiovascular events and arrhythmias. Careful safety assessments have documented the relative safety and tolerability of this agent in various patient groups. Focus has also been placed on demonstrating efficacy with regard to bowel function, symptoms, and patient-reported outcomes such as the Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms and the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life scores to support the use of prucalopride as a safe and effective therapeutic option for the management of chronic constipation.

Keywords: prucalopride, chronic constipation, 5-HT4 agonist, safety, prokinetic, PAC-QOL

Definition, epidemiology, and impact of constipation

Constipation is a common condition defined by bowel symptoms that may include infrequent or difficult passage of stool, hardness of stool, or a sensation of incomplete evacuation.1 The consensus-based Rome IV criteria incorporate many of these symptoms, defining constipation as two or more of the following symptoms in at least 25% of defecations: straining, lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal blockage, manual maneuvers to facilitate defecations, or fewer than three defecations per week. Criteria should be fulfilled for at least the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.2 The Rome criteria include patients with “functional constipation;” however, this term has been avoided in the last two American Gastroenterological Association technical reviews on constipation in consideration of the fact that there exists a subset of patients with slow-transit constipation that is not considered to be truly “functional”.1

In North America, the reported prevalence of constipation ranges from 2% to 27%, although most estimates report rates ranging from 12% to 19%.3 A prior systematic review investigating epidemiology of constipation reported worldwide prevalence rates ranging from 0.7% to 79% with an overall median of 16% and a median of 33.5% among the elderly.4 Prevalence of constipation may also vary based on sex and race, with a higher prevalence being reported among females5,6 and in nonwhite populations compared with white populations.1

The economic burden and psychosocial impact of constipation are significant. Constipation is associated with productivity losses, increased health care utilization, and impairment in quality of life (QOL).7,8 In a web-based survey conducted in the US of 557 participants, symptoms of constipation affected QOL in >50% of respondents and decreased work productivity with a mean absence of 2.4 days in 12% of respondents who worked or attended school.9 A separate survey conducted in Canada showed that among patients with self-reported constipation or functional constipation based on Rome II criteria, physical and mental components of the Short Form 36 were found to be significantly lower compared with Canadian norms and poorer QOL was observed to be a strong predictor of health care utilization.10

Estimated ambulatory visits for constipation in the US have risen dramatically over the last several decades, with recent reports estimating 8 million visits annually from 2001 to 2004, constituting 33.4% of visits with primary care providers and 14.1% of visits with gastroenterologists.11 The majority of physician visits for constipation result in a prescription for a laxative, and it has been estimated that Americans spend $800 million per year on such treatments.12 Despite the frequent use of laxatives, fiber, and other prescription medications, up to 50% of patients report they are not completely satisfied with their current treatment for constipation.9 Furthermore, the frequency of constipation-related emergency department visits increased by 41.5% from 2006 to 2011, and the aggregate national cost of constipation-related emergency department visits increased by 121.4% from 723,886,977 in 2006 to >1.6 billion in 2011 after adjustment for inflation,13 emphasizing the need for improved diagnosis and management of chronic constipation in the outpatient setting.

Pathophysiology of chronic constipation

Symptoms of constipation may be related to various underlying mechanisms, including abnormal colonic transit and defecatory disorders, which may occur in the context of slow colonic transit.14 Thus, careful consideration of the pathophysiology of chronic constipation remains important in providing targeted strategies for management and treatment.1 For example, first-line intervention for rectal evacuation disorders may include biofeedback-aided pelvic floor therapy, which has previously been demonstrated as effective and may even result in improved colonic transit.15–18 Slow colonic transit may also occur in isolation and delayed transit may serve as a surrogate marker for impaired colonic motility.19,20 The spectrum of patients may include those with colonic inertia, characterized by marked impairment in contractile responses to a meal or pharmacological stimulus. Even among patients with “normal” colonic transit, there is evidence supporting the presence of underlying colonic motor dysfunction, as reflected by reduction in colonic tone.19

Current pharmacological agents for the treatment of constipation

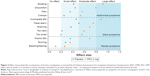

Initial steps in pharmacological management21 of constipation (Figure 1) generally begin with fiber supplementation or bulking agents followed by the use of osmotic laxatives, which may include polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based laxatives, magnesium salts, and poorly absorbed carbohydrates (eg, sorbitol and lactulose). For those with a suboptimal response to osmotic laxatives, stimulant laxatives, including bisacodyl or senna, may be effective as a supplementary agent. The majority of these agents are available over-the-counter without a prescription and are relatively inexpensive. Newer pharmacological agents currently approved for the treatment of chronic constipation include intestinal secretagogues, such as lubiprostone and linaclotide, for those who have failed first-line therapies. However, newer agents can be relatively expensive and are available by prescription only. Both lubiprostone and linaclotide facilitate intestinal chloride secretion; lubiprostone via activation of apical type 2 chloride channels and linaclotide via activation of guanylyl cyclase C. Prokinetic agents targeting 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor-4 (5-HT4) and motilin receptors have also been considered as a therapeutic approach for constipation, although most are not easily available in the US or are undergoing ongoing investigation.22 A recent review summarizing the cost of treatment for constipation reported estimated monthly costs ranging from $0.34 per month for senna to $293.02 for lubiprostone. Meanwhile, over-the-counter bulking agents such as psyllium and laxatives such as PEG 3350 were estimated to cost $14.22 and $18.25 per month, respectively.23

| Figure 1 Algorithm for management of chronic constipation. |

5-HT4 agonists for the treatment of chronic constipation

5-HT4 receptors are members of the G-protein-coupled family of receptors widely expressed throughout the gastrointestinal tract on enteric neurons24 and smooth muscle cells25 and have been extensively studied as targets for prokinetic treatment. Activation of these receptors promotes mucosal secretion and gastrointestinal motility26 through enhanced cholinergic transmission and relaxation of inhibitory circular smooth muscle.27

Several classes of 5-HT4 agonists have been developed as prokinetic agents for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders, and different agents exhibit differing levels of affinity and selectivity for the 5-HT4 receptor. Early 5-HT4 receptor agonists, including cisapride and tegaserod, were previously withdrawn from the market due to the association with adverse QT prolongation and cardiovascular side effects resulting from their lack of selectivity for 5-HT4 receptors and affinity for the human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG)-encoding potassium channel28 and 5-HT1 or 5-HT2 receptors unrelated to 5-HT4 receptor agonism.24

Unlike tegaserod and cisapride, newer highly selective 5-HT4 receptor agonists, including prucalopride,24 velusetrag,29 and naronapride (ATI-7505),30 do not display affinity for hERG channels nor 5-HT receptor subtypes associated with the previously reported arrhythmias and adverse cardiovascular effects. In fact, cardiac safety of prucalopride has been assessed in healthy volunteers through a prospective double-blind, placebo-, and active-controlled study, in which volunteers were randomized to therapeutic and supratherapeutic doses of prucalopride or placebo with moxifloxacin to show no clinically significant effects on corrected QT interval (QTc).31 A recent systematic review evaluating highly selective 5-HT4 receptor agonists on patient-important clinical efficacy outcomes and safety demonstrated that relative to control, treatments with highly selective 5-HT4 agonists were superior in improving bowel function, symptoms, and QOL while maintaining a favorable safety profile.32 Despite their potential, none of the newer 5-HT4 agonists have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of constipation in the US, and there remains misperception and confusion regarding their safety profile, even among experienced clinicians.

Focus on prucalopride

Of the different 5-HT4 agonists that have been developed, evidence for clinical efficacy is most available for prucalopride. Prucalopride is a first-in-class dihydrobenzofuran carboxamide derivative that is highly selective for the 5-HT4 receptor with potent enterokinetic properties.33 Prucalopride has been approved by the European Medicine Agency for the treatment of chronic constipation in adults in whom laxative therapy has failed34 and is now approved in several countries for the treatment of chronic constipation at doses of 2 mg/d for adults and 1 mg/d for elderly patients.35

Preclinical pharmacological and pharmacodynamic studies on prucalopride

Studies on the pharmacological profile of prucalopride demonstrating its prokinetic effects and high selectivity for the 5-HT4 receptor have been performed in several preclinical animal models. Prucalopride exhibits a high affinity only for the 5-HT4b and 5-HT4a receptors (Ki value of 8 nM and 2.5 nM, respectively) and at least a 290-fold selectivity for the 5-HT4 receptor. It has been shown to be devoid of undesirable anticholinergic and anticholinesterase activity.36 Observations have been further supported in vivo in fasted dogs where prucalopride administration caused stimulation of high-amplitude clustered contractions in the proximal colon and inhibition of distal contractile activity in a dose-dependent fashion. Contractile motility patterns were completely inhibited with administration of a 5-HT4 receptor agonist,37 suggesting the effects of prucalopride to be specifically mediated via 5-HT4 receptors.

Consistent with preclinical pharmacological studies, data from placebo-controlled studies (ie, studies utilizing inert substances without known activity as the control treatment)38 performed among healthy volunteers have shown prokinetic properties of prucalopride and effects on stool frequency and consistency in humans. Efficacy of prucalopride was shown in a placebo-controlled study performed in 50 healthy volunteers, in which treatment with prucalopride daily was associated with acceleration of overall colonic transit with no significant effects on gastric emptying or small bowel transit.39 In a separate double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study by Poen et al,40 treatment with 2 mg of prucalopride daily was associated with an increase in mean colonic transit time and significant increases in weekly stool frequency and percentage of loose or watery stools. Findings of increased gastrointestinal transit, increased stool frequency, and decreased stool consistency were also noted in a similarly designed trial by Emmanuel et al.41

Phase II trials in patients with chronic constipation

In patients with chronic constipation, data supporting the safety and efficacy of prucalopride have been shown in several Phase II clinical trials. In a double-blind Phase II trial among females with constipation, treatment with 1 mg of prucalopride daily for 4 weeks was associated with acceleration of whole gut transit compared with placebo, and subgroup analysis further revealed this effect to be limited to patients with slow transit. Treatment with prucalopride was also associated with a significant improvement in symptoms, shorter time to first bowel movement, and alterations in rectal sensitivity.42 In male and female patients with functional constipation, treatment with 1 mg or 2 mg of prucalopride resulted in a numerical improvement in mean colonic transit time compared with placebo, although results were not statistically significant. Treatment with the 1 mg dose was associated with significant increases in spontaneous complete bowel movement (SCBM) frequency while no differences in anorectal function were seen between treatment groups.43 Effects of 2 mg or 4 mg of prucalopride on gastrointestinal and colonic transit were also assessed using validated scintigraphy by investigators in 40 patients (four males and 36 females) with functional constipation without evidence of a rectal evacuation disorder. In contrast to their prior study among healthy volunteers,39 significant acceleration of overall gastric emptying and small bowel transit time was observed. The 4 mg treatment dose was associated with significant acceleration of overall colonic transit at 24 hours, but observed differences for the overall treatment group vs placebo were of borderline significance (P=0.1).44 In patients with severe constipation referred to a tertiary care center, treatment with 4 mg of prucalopride was found to significantly improve stool consistency and time to first stool. Positive effects on stool frequency and whole gut transit were observed, although these observations were not statistically significant.45 Taken together, studies on patients with chronic constipation suggested positive effects of prucalopride on gastrointestinal transit and bowel functions. However, these data remained somewhat inconclusive given the lack of significant differences seen in individual studies.

Hence, to better characterize the effects of prucalopride on colonic transit, and the relationship between transit and symptoms, an integrated analysis was recently performed combining the results of three Phase II placebo-controlled trials in patients with chronic constipation assessing the effects of prucalopride on transit and the relationship between transit and symptoms.46 A total of 280 patients were included in the analysis, 70% of whom had slow or very slow colonic transit at baseline. The results showed that treatment with prucalopride was associated with significant decreases in mean colonic transit compared with baseline for both the 2 mg (12.0 hours, P<0.001) and 4 mg (13.9 hours, P<0.001) doses, while no significant changes were observed in the placebo group. In addition, a relationship was observed between symptom severity and colonic transit with a higher proportion of patients with slow or very slow colonic transit reporting constipation symptoms as “severe” or “very severe”. Increased stool consistency was found to be correlated with increased colonic transit. The results of this analysis indicated improvement in colonic transit and stool consistency with prucalopride and suggested improved colonic transit as a contributing mechanism for reduction in constipation symptoms.

Pivotal Phase III trials

To date, there have been five large multicenter Phase III trials of prucalopride that have demonstrated improvement in bowel function, overall symptom scores, patient satisfaction, and QOL scores in patients with chronic constipation. All trials were of similar design, involving a 12-week treatment duration in which eligible participants were randomized to prucalopride or placebo after a 2–4-week run-in phase. Three pivotal trials47–49 were performed in predominantly Caucasian patients using either 2 mg or 4 mg of prucalopride. A fourth trial was later performed in a predominantly Asian population using 2 mg once daily.50 In these four trials, it was noted that only 10% were males and more recently, a fifth multicenter Phase III trial was published evaluating the efficacy and safety of prucalopride for the treatment of chronic constipation among males.51 In the three initial Phase III trials,47–49 significantly more patients randomized to prucalopride achieved the primary efficacy end point (ranging from 20% to 30% for prucalopride vs 9% to 12% for placebo) of three or more SCBMs per week as well as increases of one or more SCBMs per week from baseline compared with placebo. Treatment effects were seen for both doses of prucalopride, and analysis of secondary end points also showed that patients treated with prucalopride achieved greater satisfaction with treatment, bowel function, and an improved perception of constipation-related QOL. Completion of the three pivotal trials was followed by an open-label study52 in which patients who completed the initial Phase III studies were invited to continue treatment in two studies of similar design (PRU-INT-10 and PRU-USA-22) to assess long-term satisfaction with bowel function for treatment durations of up to 24 and 36 months. Of those participating in the blinded Phase III trials, 86% elected to proceed with the open-label study with at least 12 months of study data available for the majority (54%) of patients and a total calculated exposure to prucalopride of 1,464 patient-years at study completion. Assessment of patient satisfaction using the Patient Assessment of Constipation-QOL (PAC-QOL) scale showed that the improvement achieved in the double-blind studies with prucalopride treatment was maintained for up to 18 months and a similar improvement was seen in the first 3 months of the open-label study for patients who received placebo during the double-blind trials. Between 43% and 67% of patients achieved ≥1 point improvement in their satisfaction over the 18-month period. In total, 8% of patients discontinued the open-label study secondary to adverse events (AEs), with the most commonly reported AEs being abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, and nausea.

Clinical efficacy in special population

Müller-Lissner et al demonstrated the beneficial effects of prucalopride on bowel function, symptoms, and QOL in a 4-week randomized placebo-controlled trial in patients ≥65 years of age with chronic constipation. The effect of prucalopride on bowel movements was greatest after the first week of treatment. Safety assessments revealed a slightly higher incidence of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and headache in the treatment group consistent with larger Phase III trials. However, all AEs were considered to be only mild or moderate in severity, and no clinically relevant findings were noted with respect to cardiovascular safety or electrocardiography (ECG) variables including QTc intervals.53

Ke et al50 published the results of a large randomized placebo-controlled Phase III trial of prucalopride in patients with chronic constipation from the Asia-Pacific region. Part of the rationale for this study was the recognized potential for altered pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug profiles based on race and ethnicity. Investigators demonstrated the efficacy of prucalopride among Asians with significant improvements in bowel function, bowel symptoms, patient satisfaction, and QOL. Analysis of the primary efficacy end point showed that 33.3% prucalopride-treated patients vs 10.3% placebo-treated patients achieved a weekly average of at least three SCBMs per week over the 12-week treatment course, whereas 57% prucalopride-treated patients vs 27% placebo-treated patients experienced an average increase of one or more SCBMs per week from baseline. Significant improvements were also observed in overall QOL scores and all subscales (dissatisfaction, physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, and worries and concerns). Frequently reported AEs were diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and headache, similar to prior Phase III trials among Caucasians with no unexpected safety findings observed.

Finally, recent data published from a multicenter trial in males with chronic constipation reported prucalopride to be significantly more effective in improvement of bowel function vs placebo, with 38% of prucalopride-treated patients achieving the primary end point vs 17.7% of placebo-treated patients. The proportion of patients (47% prucalopride vs 30.4% placebo, P<0.0001) rating treatment as effective and the proportion of patients (53% prucalopride vs 39% placebo, P=0.0035) reporting at least a 1 point improvement in the PAC-QOL satisfaction scores were significantly increased in the prucalopride group.51

Comparison of prucalopride with available treatment options

To date, there has been only one randomized controlled trial of prucalopride using an active comparator, PEG 3350+E, an established osmotic laxative that is widely available for the treatment of constipation in both adults and children.54 PEG 3350+E has a significantly lower cost for 14 days of treatment compared with prucalopride,55 and in this Phase III clinical trial, investigators demonstrated noninferiority of PEG 3350+E vs prucalopride for the primary end point of the proportion of patients achieving ≥3 SCBMs during the last week of treatment. Results of patient assessments and QOL also showed that more patients randomized to PEG 3350+E rated treatment as “very” or “extremely effective”, while stool symptom, rectal symptoms, and global assessment scores also improved more with PEG 3350+E than with prucalopride. Conversely, abdominal symptoms were more improved with prucalopride after the first 7 days. Given the findings of this study, the authors argue that PEG 3350+E remains the more cost-effective treatment and should be the first-line approach for the treatment of chronic constipation. However, the long-term durability of these findings will require further scrutiny, as this study was limited to a 4-week duration due to its design in which participants were assessed in a controlled Phase I unit to allow for control of environmental factors and ensure accuracy of outcome assessments.

Currently underway is a prospective randomized multicenter trial aiming to compare the efficacy of electroacupuncture, a commonly used complementary/alternative therapy for the treatment of chronic constipation, with that of prucalopride in patients with constipation. The objectives of this Phase II study are to assess the primary outcome of the proportion of patients achieving three or more SCBMs per week as well as secondary outcomes of ≥1 increase in SCBMs per week from baseline, changes in SCBMs per week from baseline, stool consistency, and PAC-QOL.56

Patient perspectives with focus on important outcomes of patients

In order to evaluate the impact of treatment on patients with chronic constipation, all clinically relevant important outcomes of patients should be considered in efficacy analyses in clinical trials of prucalopride and other investigational agents. The impact of chronic constipation on health-related QOL is significant and has been reported to be comparable with conditions such as allergies, musculoskeletal impairments, and inflammatory bowel disease.8 Hence, the inclusion of multiple efficacy outcomes including stool frequency, stool consistency, symptoms, global patient satisfaction, and health-related QOL has been critical in allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of patient responses and perceptions. In clinical practice, focus on patient-reported symptoms is particularly important as individual bowel habits may vary and the definition of constipation may be interpreted differently by both the patient and the physician.57

All aforementioned Phase III clinical trials of prucalopride47–49 and follow-up open-label study52 have incorporated patient-reported outcomes of symptoms, satisfaction, and QOL. The Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM) is a validated questionnaire addressing 12 constipation-related symptoms scored on three subscales: stool, abdominal, or rectal symptoms for which an overall score and a score for each subscale can be determined to address patient perspectives on chronic constipation.58 This questionnaire has been shown to be internally consistent, responsive to change, and able to differentiate between groups of patients based on clinical severity of constipation. More recently, the psychometric properties of this instrument were investigated in >2,000 outpatients with chronic constipation. The relevance of the rectal domain was questioned as only 38% of patients reported symptoms of rectal tearing and thus a modified eleven-item PAC-SYM was developed to demonstrate reliability as well as correlation with health-related QOL and treatment satisfication,59 supporting its use as a measure of symptom severity in patients seeking care for treatment of chronic constipation. An integrated analysis60 combining data from the three pivotal Phase III trials47–49 to evaluate the effects of prucalopride on constipation symptoms as measured by the PAC-SYM questionnaire showed prucalopride to have a large effect on common symptoms of constipation as assessed by the PAC-SYM (Figure 2).60 The largest improvements in subscale scores were observed for abdominal symptoms and stool symptom scores, whereas smaller improvements were observed for the rectal symptoms score.

| Figure 2 Effect of prucalopride on symptoms of chronic constipation as assessed by the Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms Questionnaire (PAC-SYM). PAC-SYM effect sizes at week 12 in women in whom laxatives had failed to provide adequate relief – an integrated analysis of three identical double-blind phase III trials. |

Assessment of patient satisfaction and health-related QOL has been measured using the previously validated PAC-QOL questionnaire, a 28-item instrument consisting of an overall scale and four separate subscales: 1) physical discomfort; 2) psychosocial discomfort; 3) worries and concerns; and 4) patient satisfaction.61 Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of this instrument have been demonstrated in multinational studies to establish its utility as a comprehensive assessment of patients’ well-being.62

Due to uncertainty regarding the clinical significance of PAC-QOL scores and the clinical relevance of detecting a 1 point improvement in scores in the three pivotal Phase III trials, investigators conducted a pooled analysis to assess psychometric properties of the PAC-QOL and provide guidance for interpretation.61 Results showed the psychometric properties of the PAC-QOL among patients in the prucalopride trials to be internally consistent, reliable, and responsive. A significant relationship was observed between PAC-QOL scores and severity of constipation as measured by PAC-SYM and stool frequency, demonstrating the importance of stool frequency in the patients’ perception of constipation. Calculation of the minimum important difference using distribution- and anchor-based methods was <0.5 and <0.9, respectively, indicating a 1 point difference to be clinically relevant. Meanwhile, the majority of patients with at least a 1 point improvement in PAC-QOL scores showed consistent improvements in treatment efficacy and symptom severity. Results of this analysis served to further support the use of the PAC-QOL as an important assessment tool in measuring patient perspectives in response to treatment in both a clinical and research setting.

Recognizing the importance of patient-reported outcomes and tools such as the PAC-QOL, Tack et al63 performed an integrated analysis using data from the three pivotal Phase III trials to further investigate the relationship between health-related QOL as assessed by the PAC-QOL and symptom severity. Analysis of the relationship between PAC-QOL and PAC-SYM using data from the intention-to-treat population showed that for both the PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL, significantly more patients in the 2 mg prucalopride group achieved ≥1 point improvement in the total score after 12 weeks compared with placebo. Among patients achieving ≥1 point improvement in overall PAC-QOL score, 66% also had a ≥1 point improvement in overall PAC-SYM with a strong linear positive correlation for change in baseline to week 12 between overall PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL scores (r=0.711). Among patients who achieved the primary efficacy end point of three or more SCBMs per week over 12 weeks of treatment, 72.4% achieved an improvement of ≥1 point on the PAC-QOL satisfaction score (Figure 3).63 Results demonstrated the correlation between health-related QOL and improvement in stool frequency and symptoms in patients with chronic constipation.

| Figure 3 Association between Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) satisfaction score and primary efficacy end point of three or more spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs) per week over 12 weeks in three pivotal Phase III clinical trials. |

Safety and AEs

Documentation of safety and tolerability of highly selective 5-HT4 agonists such as prucalopride remains a critically important component in assessment of patient outcomes and responses. In all five Phase III clinical trials of prucalopride, careful safety assessments have been incorporated to document AEs and tolerability, with particular emphasis on cardiovascular risks and ECG parameters. Total number of AEs and discontinuation rates from all five Phase III trials are summarized in Table 1. In general, the most commonly reported AEs include headache, diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain (Table 2) with no major cardiovascular safety concerns being observed. In the multicenter trial performed in the US by Camilleri et al,47 AEs were reported at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 of treatment, and results of ECG, clinical laboratory tests, and physician examinations were evaluated at screening and at weeks 4 and 12. Most AEs were mild or moderate, and serious AEs were reported in 3.4% of patients receiving 4 mg of prucalopride, 1.4% of patients receiving 2 mg of prucalopride, and 3.8% of patients receiving placebo. The incidence of AEs was similar in all three treatment groups with the exception of diarrhea and headache, which were more frequently reported with prucalopride. Importantly, there were no significant differences in incidence of prolonged QTc between groups and no clinically significant cardiac events occurred with the exception of one patient with a preexisting history of mitral valve prolapse and supraventricular tachycardia in whom that condition occurred while receiving treatment with prucalopride.

| Table 2 Frequency of most commonly reported AEs in Phase III clinical trials of PRU |

Safety assessments were conducted in a similar fashion in a separate multicenter Phase III trial throughout 41 centers in the US by Quigley et al.48 The most frequently reported AEs again included headache, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and flatulence, and these were more common among patients in the prucalopride group on the first day of treatment. However, when excluding the first treatment day, incidence of AEs was similar across groups. Severe AEs were reported in 15% of patients treated with 2 mg of prucalopride, 21% of patients treated with 4 mg of prucalopride, and 10% of patients treated with placebo. Most severe AEs involved the gastrointestinal system and a higher incidence of severe headache was observed in the prucalopride groups. Incidence of serious AEs did not differ by the treatment group. The incidence of prolonged QTc was low overall, with no significant difference between groups.

In the third pivotal trial by Tack et al,49 safety assessments demonstrated that most AEs were mild or moderate, and transient. Increased AEs in the prucalopride group were noted mainly on day 1 but were otherwise similar between groups. The most common AEs were headache, nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, as noted in the other Phase III trials of similar size and design. Interestingly, severe diarrhea was not higher with prucalopride. Discontinuation secondary to AEs was highest in the group assigned to 4 mg of prucalopride. Consistent with prior reports, no clinically significant differences in ECG parameters or incidence of QTc prolongation were observed between groups.

Safety assessments in the Phase III trial conducted among patients from the Asia-Pacific region50 showed that the total proportion of patients experiencing at least one AE was higher in the prucalopride-treated group than in the placebo-treated group. Serious AEs occurred in 1.2% of patients treated with prucalopride and 2.0% of patients treated with placebo, while AEs leading to discontinuation of study drug occurred in 3.2% of patients treated with prucalopride and 1.2% of patients treated with placebo. The most commonly reported AEs included diarrhea, headache, nausea, and abdominal pain, and all occurred more frequently in the prucalopride-treated group. The incidence of treatment-emergent cardiovascular events, including palpitations, cardiovascular ischemic events, arrhythmias, and QT prolongation, was low overall and similar between treatment groups. In the prucalopride group, there was one patient with ECG signs of myocardial ischemia. Abnormal values in ECG parameters, including QT interval, were not observed in patients with normal baseline values after treatment with prucalopride.

In the most recently published Phase III trial among males with chronic constipation,51 a total of 42.4% of prucalopride-treated patients and 34.4% of placebo-treated patients experienced at least one treatment-emergent AE (TEAE), although the difference was not significant. The most commonly reported TEAEs associated with prucalopride were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and headache. Most TEAEs were mild or moderate, and serious TEAEs were reported in one patient in the prucalopride group and four patients in the placebo group. Treatment discontinuation secondary to AEs was similar between groups (3.3% with prucalopride vs 3.8% with placebo). Overall incidence of cardiovascular AEs was low (two patients in the placebo group with angina and myocardial ischemia and one patient in the prucalopride group with coronary artery occlusion). There was one patient with QT prolongation at week 4 in the prucalopride group; however, values returned to normal at week 12 and study treatment continued.

Safety and tolerability of prucalopride have also been evaluated in elderly patients with chronic constipation residing at nursing homes in a Phase II dose-escalation study for up to 4 weeks of treatment, which included rigorous safety assessments comprising documentation of patient-reported AEs, pharmacokinetic assessments, serial laboratory tests, evaluation with serial ECGs, and continuous Holter monitoring per study protocol.64 It should be noted that 88% of the study population had a history of relevant cardiovascular disease. Overall, AEs were reported in 50% of patients treated with placebo, 85.7% of patients treated with 0.5 mg of prucalopride, 70.8% of patients treated with 1 mg of prucalopride, and 69.2% of patients treated with 2 mg of prucalopride. The most commonly reported AEs included diarrhea, abdominal pain, and headache. Diarrhea and headache were more commonly reported in the prucalopride groups and abdominal pain was more commonly reported in the placebo group. Most AEs were mild or moderate in severity. Evaluation of cardiovascular parameters revealed no clinically significant differences in change in heart rate or ECG parameters (PR, QT, QTcB, or QTcF intervals) between groups. Increase in QTc interval from baseline resulting in a prolonged QTc of 473 ms was observed in one female patient with a history of a pacemaker and extensive cardiovascular disease. Holter monitoring did not reveal any significant differences in the incidence of arrhythmic or supraventricular events between groups. Findings suggested prucalopride to be safe and well tolerated even among elderly patients with chronic constipation.

Factors associated with the occurrence of TEAEs have been further assessed in a recent integrated analysis to show a higher prevalence of diarrhea, headache, and nausea with prucalopride compared with placebo. Interestingly, it was noted that diarrhea occurred at a higher frequency among Asians, while headache, abdominal pain, and nausea occurred at a lower frequency among Asians compared with non-Asians.35 In summary, the evidence from multiple clinical trials and follow-up analyses using pooled data has repeatedly demonstrated the relative safety of prucalopride for the treatment of chronic constipation.

Postmarketing surveillance (results of a Phase IV clinical trial)

Given the promising results from the initial Phase III studies of prucalopride in patients with chronic constipation as well as the results of the open-label follow-up study, a Phase IV clinical trial investigating long-term efficacy and safety was recently undertaken at 50 sites across Europe.65 In this trial, adults with chronic constipation were randomized to 24 weeks of treatment with either placebo or prucalopride. The primary efficacy end point was the proportion of patients achieving an average of three or more SCBMs per week over the 24-week treatment duration. Secondary end points focused on safety, tolerability, and effects on health-related QOL. A total of 182 patients were recruited and enrolled in each treatment arm, with 126 patients in the placebo group and 135 patients in the prucalopride group completing the study. The primary efficacy end point was achieved by 25.1% in the prucalopride group and 20.7% in the placebo group using the intention-to-treat population with no statistically significant difference between groups. Analysis of the first 12 weeks as well as sensitivity analyses using the perprotocol and completer populations showed similar findings. However, an additional sensitivity analysis using a generalized linear model showed a significant difference with a greater proportion of responders in the prucalopride group compared with placebo over 12 and 24 weeks. Interestingly, analysis of secondary end points revealed the proportion of patients reporting a ≥1 point improvement in the PAC-SYM score to be significantly greater in the placebo group than in the prucalopride group, whereas the proportion of patients with an improvement in PAC-QOL did not significantly differ between groups. Results of safety assessments were similar to those in previously published trials. No significant differences were observed between groups with respect to total proportion of patients experiencing at least one TEAE or serious AEs, and no clinically significant changes were observed in QT prolongation or ECG parameters throughout the study duration. The most commonly reported AEs included headache, abdominal pain, and nausea. The authors were unable to explain the lack of efficacy of prucalopride in this long-term trial, despite the use of several sensitivity analyses. However, further consideration may be given to the larger than previously observed placebo response rate as well as the possible impact of patient selection without careful exclusion of patients with an underlying rectal evacuation disorder. When combined with data from prior Phase III trials in an integrated analysis, results continue to demonstrate global efficacy and a favorable safety profile of prucalopride for the treatment of chronic constipation.66

Conclusion

Chronic constipation remains a common and an important clinical condition with a substantial impact on health care utilization and health-related QOL. Newer agents now available for treatment include the highly selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist, prucalopride. Efficacy and safety of prucalopride have been demonstrated in multiple randomized clinical trials, and special emphasis has been placed on examining potential cardiovascular risks to show prucalopride to be a safe treatment option for patients with chronic constipation, including special populations such as elderly patients. Clinical trial data have also provided evidence to support its efficacy through assessment of constipation symptoms and health-related QOL scores, which serve to reflect patient-important outcome measures beyond that of stool frequency and bowel function.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218–238. | ||

Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1393–1407. | ||

Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):750–759. | ||

Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(1):3–18. | ||

Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Cumulative incidence of chronic constipation: a population-based study 1988–2003. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(11–12):1521–1528. | ||

Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(7):917–930. | ||

Neri L, Basilisco G, Corazziari E, et al. Constipation severity is associated with productivity losses and healthcare utilization in patients with chronic constipation. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(2):138147. | ||

Belsey J, Greenfield S, Candy D, Geraint M. Systematic review: impact of constipation on quality of life in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(9):938–949. | ||

Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(5):599–608. | ||

Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, Thompson WG, Rance L. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(8):1986–1993. | ||

Shah ND, Chitkara DK, Locke GR, Meek PD, Talley NJ. Ambulatory care for constipation in the United States, 1993–2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(3):1746–1753. | ||

Faigel DO. A clinical approach to constipation. Clin Cornerstone. 2002;4(4):11–21. | ||

Sommers T, Corban C, Sengupta N, et al. Emergency department burden of constipation in the United States from 2006 to 2011. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(4):572–579. | ||

Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1510–1518. | ||

Chiarioni G, Salandini L, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dysfunction, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):86–97. | ||

Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassotti G. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657–664. | ||

Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback, sham feedback, and standard therapy for dyssynergic defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331–338. | ||

Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, Ringel Y, Drossman D, Whitehead WE. Randomized, controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428–441. | ||

Ravi K, Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Rhoten D, Bakken T, Zinsmeister AR. Phenotypic variation of colonic motor functions in chronic constipation. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(1):89–97. | ||

Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, di Lorenzo C, et al. American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society consensus statement on intraluminal measurement of gastrointestinal and colonic motility in clinical practice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(12):1269–1282. | ||

Vazquez Roque M, Bouras EP. Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:919–930. | ||

Jiang C, Xu Q, Wen X, Sun H. Current developments in pharmacological therapeutics for chronic constipation. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5(4):300–309. | ||

Wald A. Constipation: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2016;315(2):185–191. | ||

De Maeyer JH, Lefebvre RA, Schuurkes JA. 5-HT4 receptor agonists: similar but not the same. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(2):99–112. | ||

Prins NH, Shankley NP, Welsh NJ, et al. An improved in vitro bioassay for the study of 5-HT(4) receptors in the human isolated large intestinal circular muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129(8):1601–1608. | ||

Hegde SS, Eglen RM. Peripheral 5-HT4 receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10(12):1398–1407. | ||

Briejer MR, Akkermans LM, Schuurkes JA. Gastrointestinal prokinetic benzamides: the pharmacology underlying stimulation of motility. Pharmacol Rev. 1995;47(4):631–651. | ||

Mohammad S, Zhou Z, Gong Q, January CT. Blockage of the HERG human cardiac K+ channel by the gastrointestinal prokinetic agent cisapride. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(5 pt 2):H2534–H2538. | ||

Smith JA, Beattie DT, Marquess D, Shaw JP, Vickery RG, Humphrey PP. The in vitro pharmacological profile of TD-5108, a selective 5-HT(4) receptor agonist with high intrinsic activity. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2008;378(1):125–137. | ||

Camilleri M, Vazquez-Roque MI, Burton D, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of a novel prokinetic 5-HT receptor agonist, ATI-7505, in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(1):30–38. | ||

Mendzelevski B, Ausma J, Chanter DO, et al. Assessment of the cardiac safety of prucalopride in healthy volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and positive-controlled thorough QT study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(2):203–209. | ||

Shin A, Camilleri M, Kolar G, Erwin P, West CP, Murad MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: highly selective 5-HT4 agonists (prucalopride, velusetrag or naronapride) in chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(3):239–253. | ||

Frampton JE. Prucalopride. Drugs. 2009;69(17):2463–2476. | ||

Camilleri M, Deiteren A. Prucalopride for constipation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(3):451–461. | ||

Leelakusolvong S, Ke M, Zou D, et al. Factors predictive of treatment-emergent adverse events of prucalopride: an integrated analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Gut Liver. 2015;9(2):208–213. | ||

Briejer MR, Bosmans JP, Van Daele P, et al. The in vitro pharmacological profile of prucalopride, a novel enterokinetic compound. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;423(1):71–83. | ||

Briejer MR, Prins NH, Schuurkes JA. Effects of the enterokinetic prucalopride (R093877) on colonic motility in fasted dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2001;13(5):465–472. | ||

Misra S. Randomized double blind placebo control studies, the “Gold Standard” in intervention based studies. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2012;33(2):131–134. | ||

Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, McKinzie S. Selective stimulation of colonic transit by the benzofuran 5HT4 agonist, prucalopride, in healthy humans. Gut. 1999;44(5):682–686. | ||

Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Van Dongen PA, Meuwissen SG. Effect of prucalopride, a new enterokinetic agent, on gastrointestinal transit and anorectal function in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(11):1493–1497. | ||

Emmanuel AV, Kamm MA, Roy AJ, Antonelli K. Effect of a novel prokinetic drug, R093877, on gastrointestinal transit in healthy volunteers. Gut. 1998;42(4):511–516. | ||

Emmanuel AV, Roy AJ, Nicholls TJ, Kamm MA. Prucalopride, a systemic enterokinetic, for the treatment of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(7):1347–1356. | ||

Sloots CE, Poen AC, Kerstens R, et al. Effects of prucalopride on colonic transit, anorectal function and bowel habits in patients with chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(4):759–767. | ||

Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Thomforde G, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR. Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(2):354–360. | ||

Coremans G, Kerstens R, De Pauw M, Stevens M. Prucalopride is effective in patients with severe chronic constipation in whom laxatives fail to provide adequate relief. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Digestion. 2003;67(1–2):82–89. | ||

Emmanuel A, Cools M, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R. Prucalopride improves bowel function and colonic transit time in patients with chronic constipation: an integrated analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(6):887–894. | ||

Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(22):2344–2354. | ||

Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation – a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):315–328. | ||

Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut. 2009;58(3):357–365. | ||

Ke M, Zou D, Yuan Y, et al. Prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in patients from the Asia-Pacific region: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(11):999–e541. | ||

Yiannakou Y, Piessevaux H, Bouchoucha M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of prucalopride in men with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(5):741–748. | ||

Camilleri M, Van Outryve MJ, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Clinical trial: the efficacy of open-label prucalopride treatment in patients with chronic constipation – follow-up of patients from the pivotal studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(9):1113–1123. | ||

Müller-Lissner S, Rykx A, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of prucalopride in elderly patients with chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(9):991–998, e255. | ||

Cinca R, Chera D, Gruss HJ, Halphen M. Randomised clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350+electrolytes versus prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation – a comparison in a controlled environment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(9):876–886. | ||

NHS Regional Drug and Therapeutics Centre. Cost Comparison Charts. Oct 2015. Newcastle: NHS Regional Drug and Therapeutics Centre; 2015. | ||

Liu B, Wang Y, Wu J, et al. Effect of electroacupuncture versus prucalopride for severe chronic constipation: protocol of a multi-centre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:260. | ||

Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, Aframian R, Kuznitz D, Reichman S. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract. 1996;13(2):156–159. | ||

Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, Taylor L, Miner P Jr. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(9):870–877. | ||

Neri L, Conway PM, Basilisco G; Laxative Inadequate Relief Survey (LIRS) Group. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM) among patients with chronic constipation. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1597–1605. | ||

Tack J, Stanghellini V, Dubois D, Joseph A, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R. Effect of prucalopride on symptoms of chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(1):21–27. | ||

Dubois D, Gilet H, Viala-Danten M, Tack J. Psychometric performance and clinical meaningfulness of the Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life questionnaire in prucalopride (RESOLOR) trials for chronic constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(2):e54–e63. | ||

Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, McDermott A, Chassany O. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(5):540–551. | ||

Tack J, Camilleri M, Dubois D, Vandeplassche L, Joseph A, Kerstens R. Association between health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with chronic constipation: an integrated analysis of three phase 3 trials of prucalopride. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(3):397–405. | ||

Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Safety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(12):1256–e117. | ||

Piessevaux H, Corazziari E, Rey E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of long-term treatment with prucalopride. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27(6):805–815. | ||

Camilleri M, Piessevaux H, Yiannakou Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of prucalopride in chronic constipation: an integrated analysis of six randomized, controlled clinical trials. Dig Dis Sci. Epub 2016 Apr 7. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.