Back to Journals » International Medical Case Reports Journal » Volume 11

Mixed connective tissue disease complicated by heart failure in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: management challenges in a resource-limited economy

Authors Adewuya OA , Adebayo RA , Ajibade AI , Odunlami GJ, Akintomide AO, Ogunyemi SA, Ajayi OE, Adetiloye AO , Omisore AD, Olanipekun OA, Owolabi AO, Amjo I, Akinyele OA , Bamgboje AO, Balogun MO

Received 14 September 2017

Accepted for publication 22 June 2018

Published 2 November 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 307—312

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S151693

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ronald Prineas

Video abstract presented by Oladapo A Adewuya.

Views: 1218

Oladapo A Adewuya,1 Rasaaq A Adebayo,1 Adeola I Ajibade,2 Gbenga J Odunlami,2 Anthony O Akintomide,1 Suraj A Ogunyemi,1 Olufemi E Ajayi,1 Adebola O Adetiloye,3 Adeleye D Omisore,4 Oladipo A Olanipekun,1 Adeyinka O Owolabi,1 Ifeoluwa Amjo,1 Olumide A Akinyele,1 Abayomi O Bamgboje,1 Michael O Balogun1

1Department of Cardiology, 2Department of Rheumatology, 3Department of Pulmonology, 4Department of Radiology, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Osun, Nigeria

Background: Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD; also known as Sharp’s syndrome) is a rare autoimmune inflammatory disorder characterized by high titer of U1 ribonucleoprotein (U1RNP) antibody and clinical and serological overlap of systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, and polymyositis. The diagnosis is based on clinical and serological factors in criteria such as Alarcon-Segovia, Khan, Kusakawa, and Sharps. Cardiac disease can be a complication of connective tissue disease (CTD). There are few reports in Africa.

Aims: To present MCTD as underlying cause of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and highlight challenges of investigations and treatment.

Objectives: To highlight the first case in our center and discuss the cardiac, respiratory, and rheumatologic management.

Patient and methods: We present a 52-year-old woman with 3 weeks history of productive cough with whitish sputum, severe dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, right sided abdominal pain, leg swellings, a one year history of recurrent fever, Raynaud’s phenomenon, small joint swellings and deformities with pain in both hands.

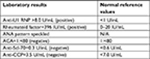

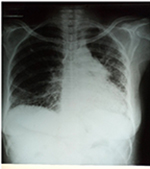

Results: On examination there was microstomia, tethered forehead and lower eyelid skin, tender swelling of the interphalangeal joints and arthritis mutilans. Laboratory findings showed estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/kg/min/1.73 m2, U1RNP antibody levels were eight times upper limit of normal, elevated rheumatoid factor, speckled antinuclear antibody pattern, negative anticentromere antibody, anti Scl-70 and anticyclic citrullinated peptide. Chest X-ray/CT revealed pulmonary fibrosis. Echocardiography findings showed reduced ejection fraction of 40%, elevated pulmonary arterial pressure at rest of 60.16 mmHg. The patient showed improvement on antifailure drugs, but prednisolone was stopped for sudden reversal of previously controlled stage 2 hypertension (HTN), and the patient was discharged in a stable condition. Difficulties ensued in obtaining prompt definite results due to the unavailability of serologic tests in the hospital, and the tests were done outside the state and country.

Conclusion: Identifying MCTD is critical, especially in patients requiring steroids that may worsen systemic HTN and heart failure. There is a need to have definitive investigative facilities for such patients in hospitals.

Keywords: mixed connective tissue disorder, U1RNP, arthritis mutilans PAH, HFrEF, prednisolone

Introduction

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a rare systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease mainly diagnosed by clinical and serologic criteria.1–3 There are some common underlying causes of heart failure in our environment, and MCTD is a rare cause of heart failure with unknown reports in Africa.4 We hereby present a case of MCTD complicated by heart failure with the associated management challenges in our resource-limited economic environment. The way we overcame the challenges may be useful for others in similar circumstances in addition to adding information to the local and international databases about MCTD. The prevalence of MCTD in Africa is 0.11%.3

Case

A 52-year-old woman presented with cough productive of whitish sputum, bilateral leg swelling, facial puffiness, right-sided abdominal pain, and severe difficulty in breathing for over 3 weeks prior to presentation. She is a computer operator and had no prior exposure to occupational lung disease hazards.

There were high-grade intermittent fevers, chills, rigors, headache, and vomiting on several occasions about a week before presentation.

Difficulty in breathing was insidious at onset, initially on exertion, and progressed to become worse at rest, with paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, palpitations, easy fatigability, and early satiety.

There is a year history of recurrent shoulder, fingers, knee, joint, and muscle pains with swellings, Raynaud’s phenomenon, deformities, and stiffness of the hands. She has been postmenopausal for 7 years and not on hormone replacement therapy. Medical history was unremarkable, and review of systems was essentially normal.

On examination

The blood pressure was 180/110 mmHg in the sitting position and 188/115 mmHg in standing position (stage 2 hypertension [HTN]), pulse rate was 120 beats/minute, respiratory rate was 28 breaths/minute, and temperature was 38°C. The patient suffered from microstomia, tethered forehead skin, lower eyelids, tender swelling of the interphalangeal (IP) joints, arthritis mutilans (la main en lorgnette; Figure 1), and bilateral pitting pedal edema up to the midlegs. There were bronchial breath sounds, coarse crepitations in left lower lung zones, bibasal fine crepitations, thickened arterial wall, locomotor brachialis, raised jugular venous pressure of 10 cm H2O, hyperdynamic precordium, apex beat in the sixth left intercostal space anterior axillary line (LICS AAL) heaving, left parasternal heave, and heart sounds (HS) – 1, 2, 3, and P2>A2. There was a tricuspid regurgitation murmur (pansystolic), enlarged liver 6 cm below the right costal margin, with a span of 14cm, tender, firm and a smooth surface.

| Figure 1 Arthritis mutilans of both hands. |

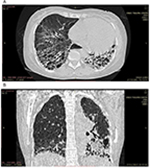

Laboratory data revealed a hemoglobin level of 10.0 g/dL, hematocrit of 30%, and white blood cell count of 4,300/mm3 with 72% segmented neutrophils and 28% lymphocytes. Film appearance showed anisocytosis, macrocytosis, microcytosis and was positive for Plasmodium falciparum (malaria parasite). Estimated glomerular filtration rate was <60 mL/kg/min/1.73 m2 and rheumatologic tests are shown in Table 1. Chest X-ray revealed features of pulmonary fibrosis secondary to connective tissue disease (CTD), with features of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as shown in Figure 2, but no pleural effusions. In Figure 3, chest CT showed basal predominance, mosaic pattern, and thickening of intralobular septae. Hand X-rays (not shown) revealed global periarticular osteopenia and soft tissue swelling over the IP joints, complete resorption of the right second and eighth middle phalanges, left third and fifth phalanges, and crowding of the carpal bones. Liver function tests (LFTs) were within normal limits. Electrocardiography showed a rate of 94 beats/minute, left axis deviation, right atrial enlargement, normal ventricles and T wave inversions >2 mm in multiple leads. Echocardiography revealed a hypokinetic interventricular septum, mild aortic, mitral and tricuspid regurgitation, grade 1 diastolic dysfunction, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, an ejection fraction of 40%, no pericardial effusion and pulmonary arterial pressure of 60.1 mmHg.

Treatment

On admission the patient was treated immediately for malaria with an adult dose for patients 35 kg or greater which is artemether+lumefantrine 80/480 mg one tab orally two times daily for 3 days. She was commenced on both oral and intravenous antifailure drugs and antibiotics namely, aldactone 25 mg, lisinopril 5 mg, lasix 60 mg, ramipril 10 mg, digoxin 0.125 mg, warfarin 2.5 mg (goal international normalized ratio, 2–3), clexane 40 IU, augmentin 600 mg intravenous q12h, clarithromycin 500 mg IV q12h, with daily weighing and monitoring of fluid input and output.

Treatment with 20 mg prednisolone orally once daily was started on the 18th day of admission, and joint pains, stiffness, and myalgia gradually improved. Two days after commencement of prednisolone, previously controlled blood pressure from 180/110 mmHg to 130/80 mmHg, increased back to 186/100 mmHg with clinical deteriorations evidenced by worsening dyspnea at rest, orthopnea, and palpitations. Prednisolone was discontinued on 22nd day of admission with resultant reduction in blood pressure to 130/70 mmHg and improvement in clinical status. A provisional diagnosis of acute heart failure precipitated by CTD was made but could not be confirmed due to initial lack of serological results. She was discharged home in a stable condition 25 days after admission and was asked to report after 2 weeks to both Cardiology and Rheumatology clinics for follow-up. Serological tests were eventually done outside the state and country because facilities for the tests were not available within the hospital.

Discussion

Even though MCTD has generally a good prognosis, significant cardiac involvement is rare.5 Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), inflammatory myopathies, systemic sclerosis, and sarcoidosis are among CTDs with severe cardiovascular association; this is due to numerous causative features such as micro/macrovascular disease, myopericarditis, myocardial fibrosis, coronary artery disease, pulmonary hypertension (PH), and finally cardiac failure.6,15 Concentric intimal proliferation and plexogenic pulmonary arteriopathy were described at autopsy as evidence for PH in young females who were diagnosed with MCTD.7 Briasoulis et al8 reported a young woman with new-onset heart failure with features suggesting cardiac tamponade and a related diagnosis of progressive MCTD associated with severe hypothyroidism, and despite prompt recognition and rapid management, she worsened and died within 4 weeks. Although MCTD has been known to be widely associated with PH, the pathogenesis of other cardiovascular manifestations such as left heart failure that could lead to right heart failure is not well understood. Kawano-Dourado et al17 in a study of 39 MCTD patients found that functional and radiologic alterations suggestive of interstitial lung disease in long-term MCTD patients were prevalent. Caminati et al18 mentioned that PH is a well-known outcome of ILDs associated with CTDs.

Undiagnosed HTN overtime, in the setting of an unrecognized MCTD, may lead to left heart failure and, with the concomitant PH, culminated in biventricular failure. Ungprasert et al19 reported that cardiac involvement was common among MCTD patients and was one of the leading causes of mortality. Similarly, Schwagten et al9 described combined systolic and diastolic heart failures as the first presentation of MCTD in a middle-aged female, and Gunnarsson et al16 in a nationwide multicenter cohort of 147 adult MCTD patients found that the prevalence of PH is much lower than expected from previous studies but confirm the seriousness of the disease complication. On the other hand, pulmonary manifestations have been drawing attention as they are found in more than 50% of the patients with MCTD.10 However, PAH and Raynaud’s phenomenon of the small vessels of the heart, similar to that observed in the fingers, are some of the most important cardiac lesions in MCTDs.11 Similarly, Hajas et al12 in a prospective study of 280 patients with MCTD found that overall, PAH remained the leading cause of death in patients with MCTD and that the prevalence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, malignancy, and thrombotic events increased during the disease course of MCTD.

Whitlow et al13 described a young black woman with clinical and serologic features of MCTD who developed myocarditis, congestive heart failure, and ventricular ectopic activity with high titer of antibody to U1 ribonucleoprotein (U1RNP). The combination of features is the core of criteria by Sharp,20 Alarcón-Segovia and Villareal,21 and Khan and Appeboom22 in the presence of synovitis. MCTD is diagnosed by these criteria with a focus on a high U1RNP titer: synovitis, PAH, and Raynaud’s phenomenon in patients.2 Among the rheumatic diseases, the diagnosis of well-established rheumatoid arthritis, progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), dermatomyositis–polymyositis, and SLE is usually obvious, even though some cases display the characteristic of more than one rheumatic disease and are referred to as “overlap” syndromes.

Most of these have the features of two to three rheumatic diseases, such as SLE, PSS, and PM or DM. Sharp20 designated an overlap syndrome of SLE, generalized scleroderma, and PM, which they considered to be a novel class of a “rheumatic disease syndrome dissimilar from the overlap syndromes” and termed it “mixed connective tissue disease”. The discrete feature of this model was the high titer of antibodies to a saline extractable nuclear antigen, which were isolated into ribonucleoprotein found in a lesser number of patients with classical PSS and SLE.7 Patients with MCTD may show a favorable response to corticosteroid therapy and a benign course, but the presence of cardiorespiratory complications may spell a rapid devastating clinical course in patients.

In our case, a major treatment challenge among others was that the onset of MCTD could not be accurately ascertained, so the temporal relationship between MCTD and cardiac problems was unclear, but as she presented with acute decompensated heart failure, there was prompt management with antifailure drugs with clinical improvement, but with persistence of the rheumatologic manifestations, such as fever, polyarthritis, joint swelling, stiffness, and pain, the patient responded positively, but briefly, to the administration of prednisolone with resulting sudden deterioration in clinical status and impending death, which led to its immediate withdrawal.

Another treatment challenge was the delay in obtaining prompt serology to confirm the suspected CTD at early stage due to the unavailability of the serologic lab tests in our hospital.

Furthermore, a declining renal status prompted consideration for renal replacement therapy. Immune complex glomerulonephritis with MCTD has often been reported; in addition, MCTD associated with myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody positive polyangiitis occurred in a patient with advanced renal failure, anemia, and pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage and died on the 16th day of admission.14

On echocardiography, our patient had several myocardial involvements, and Lash et al15 reported a relatively poor prognosis in MCTD patients with primary myocardial involvement as in SLE.

We believe that our patient benefited from the prompt management of acute heart failure complicating MCTD, but we encountered difficulties in establishing an early link between both entities.

Conclusion

Identifying MCTD is critical, chiefly in patients requiring glucocorticoids or steroids that may worsen systemic HTN and heart failure. There is a need to have definitive investigative facilities for such patients in hospitals.

Ethics approval

The ethics and research committee approval was obtained before the commencement of the report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Martínez-Barrio J, Valor L, López-Longo FJ. Facts and controversies in mixed connective tissue disease. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;150(1):26–32. | ||

Alarcón-Segovia D, Cardiel MH. Comparison between 3 diagnostic criteria for mixed connective tissue disease. Study of 593 patients. J Rheumatol. 1989;16(3):328–334. | ||

Missounga L, Ba JI, Nseng Nseng Ondo IR, et al. Mixed connective tissue disease: prevalence and clinical characteristics in African black, study of 7 cases in Gabon and review of the literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:162. | ||

Adebayo RA, Akinwusi PO, Balogun MO, et al. Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of patients presenting at Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria: a prospective study of 2501 subjects. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:541–544. | ||

Lundberg IE. Cardiac involvement in autoimmune myositis and mixed connective tissue disease. Lupus. 2005;14(9):708–712. | ||

Mavrogeni S, Markousis-Mavrogenis G, Koutsogeorgopoulou L, Kolovou G. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging: clinical implications in the evaluation of connective tissue diseases. J Inflamm Res. 2017;10:55–61. | ||

Ueda N, Mimura K, Maeda H, et al. Mixed connective tissue disease with fatal pulmonary hypertension and a review of literature. Virchows Arch A. 1984;404(4):335–340. | ||

Briasoulis A, Halpern D, Bhatti M, Dodell G, Herzog E. Acute biventricular failure as a sequela of multiple autoimmune disorders. Can J Cardiol. 2012;28(5):611.e7–e9. | ||

Schwagten B, Verheye S, Van den Heuvel P. Combined systolic and diastolic heart failure as the first presentation of mixed connective tissue disease. Acta Cardiol. 2007;62(4):421–423. | ||

Derderian SS, Tellis CJ, Abbrecht PH, Welton RC, Rajagopal KR. Pulmonary involvement in mixed connective tissue disease. Chest. 1985;88(1):45–48. | ||

Tani C, Carli L, Vagnani S, et al. The diagnosis and classification of mixed connective tissue disease. J Autoimmun. 2014:48–49:46–49. | ||

Hajas A, Szodoray P, Nakken B, et al. Clinical course, prognosis, and causes of death in mixed connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(7):1134–1142. | ||

Whitlow PL, Gilliam JN, Chubick A, Ziff M. Myocarditis in mixed connective tissue disease. Association of myocarditis with antibody to nuclear ribonucleoprotein. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(7):808–815. | ||

Kitaura K, Miyagawa T, Asano K, et al. Mixed connective tissue disease associated with MPO-ANCA-positive polyangiitis. Intern Med. 2006;45(20):1177–1182. | ||

Lash AD, Wittman AL, Quismorio FP Jr. Myocarditis in mixed connective tissue disease: clinical and pathologic study of three cases and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1986;15(4):288–296. | ||

Gunnarsson R, Andreassen AK, Molberg Ø, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary hypertension in an unselected, mixed connective tissue disease cohort: results of a nationwide, Norwegian cross-sectional multicentre study and review of current literature. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(7):1208–1213. | ||

Kawano-Dourado L, Baldi BG, Kay FU, et al. Pulmonary involvement in long-term mixed connective tissue disease: functional trends and image findings after 10 years. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(2):234–240. | ||

Caminati A, Cassandro R, Harari S. Pulmonary hypertension in chronic interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(129):292–301. | ||

Ungprasert P, Wannarong T, Panichsillapakit T, et al. Cardiac involvement in mixed connective tissue disease: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171(3):326–330. | ||

Sharp GC. Diagnostic criteria for classification of MCTD. Mixed connective tissue disease and antinuclear antibodies. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1987:23–32. | ||

Alarcon-Segovia D, Villareal M. Classification and diagnostic criteria for mixed connective tissue disease. In: Kasukawa R, Sharp GC, editors. Mixed connective tissue disease and antinuclear antibodies. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1987:33–40. | ||

Kahn MF, Appeboom T. Syndrome de Sharp. In: Kahn MF, Peltier AP, Meyer O, Piette JC, editors. Les Maladies Systemiques. 3rd ed. Paris: Flammarion; 1991:545–556. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.