Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 14

Microinvasive Glaucoma Surgical Training in United States Ophthalmology Residency Programs

Authors Yim CK, Teng CC , Warren JL, Tsai JC , Chadha N

Received 23 March 2020

Accepted for publication 27 May 2020

Published 26 June 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 1785—1789

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S255103

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Cindi K Yim,1,2 Christopher C Teng,3 Joshua L Warren,4 James C Tsai,2 Nisha Chadha2

1USC Roski Eye Institute, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; 2Department of Ophthalmology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai/New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, Eye and Vision Research Institute, New York, NY, USA; 3Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA; 4Department of Biostatistics, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Correspondence: Nisha Chadha

Department of Ophthalmology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 17 E 102nd Street, 8th Floor West, New York, NY 10029, USA

Tel +1 212-241-0949

Fax +1 212-241-9994

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The emergence of microinvasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) has expanded glaucoma management options. Resident experience with these novel procedures is unclear as no residency minimums exist for them, nor are they part of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) procedure logs. The purpose of this study was to assess resident experience with MIGS in ACGME ophthalmology residency programs across the United States.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional survey study of resident MIGS experience. A survey was mailed to program directors of ACGME-accredited ophthalmology residency programs (N = 118) in January 2017. Descriptive analyses were used to characterize the respondent demographics. Chi-square, paired t-tests, and McNemar’s tests were used to analyze the geographical distribution and frequency of MIGS experience.

Results: A total of 30 out of 118 (25%) residency program directors across all geographic regions responded. Most incorporated both MIGS lecture (87%) and wet lab (73%) didactics into their curriculum. Only 27% felt that MIGS should be part of ACGME requirements. The most common MIGS taught were iStent (70%), endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (50%), and trabectome (40%). Few residents had completed MIGS procedures as the primary surgeon by graduation. Eleven out of 30 program directors (37%) did not feel that the experience was adequate for independent practice.

Conclusion: This study suggests that residents are exposed to some MIGS procedures during training, but program directors did not feel that the experience was adequate for independent practice. Further research is necessary to understand the barriers to integrating MIGS training into residency programs.

Keywords: MIGS, ophthalmology education, resident education, surgical education

Introduction

The advent of microinvasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) techniques has ushered glaucoma surgery into a new era. MIGS procedures share five important features: microincision, minimal trauma, ability to decrease intraocular pressure (IOP), high safety profile and rapid recovery.1–3 Because the conjunctiva and sclera are left largely intact, these operations do not preclude future traditional glaucoma surgical procedures, such as trabeculectomy or glaucoma drainage implant.

MIGS have expanded surgical options for glaucoma patients, particularly if they are undergoing cataract extraction, as these techniques can be combined with cataract extraction to enhance IOP reduction at the time of cataract surgery.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has a case log system that allows residents to document the breadth of their surgical experience during residency. The ACGME’s surgical Review Committees oversee these case logs to ensure that residents have a variety of experiences and adequate volume during training. Minimum number requirements exist and represent expectations for training experience, not the achievement of competence.

Presently, no residency minimums exist for MIGS procedures, nor are they part of ACGME resident procedure logs. This study aims to assess the current state of MIGS training in ophthalmology residency programs throughout the United States.

Materials and Methods

A paper survey was mailed to all residency program directors of ACGME-accredited ophthalmology residency training programs across the United States (N = 118) in January 2017. The survey consisted of 13 questions inquiring about resident training experience with MIGS procedures, and program director attitudes towards MIGS in the context of residency training requirements (Supplemental Material). Specifically, program directors were queried on resident experience with the following MIGS: iStent, trabectome, endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP), Kahook blade goniotomy, Cypass, Trab360, Xen gel stent, and Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy (GATT). Pre-paid postage was available for program directors to anonymously return completed surveys. Geographic location was determined from postage stamps on returned surveys, but no identifying information was collected. The study was determined to be exempt by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board because it was a survey study, and the recorded information did not identify subjects, placing them at minimal risk.

Respondents were asked to complete the entire survey. Reported percentages are based on the number of responses to each individual question. Descriptive analyses were performed on the results using SPSS (version 26; SPSS, Inc). Chi-square, paired t-tests, and McNemar’s tests were used to analyze the geographical distribution of where and which MIGS techniques are taught, and frequency of MIGS technique use.

Results

A total of 30 out of 118 (25%) residency program directors responded to the survey. Respondents were categorized into four different geographical groups based off the US Census Regions and Divisions of the United States: West, Midwest, Northeast, and South.4 Of the program directors who responded, 9 (30%) were from Midwest programs, 6 (20%) from Northeast programs, 10 (33%) from Southern programs, and 5 (17%) from Western programs.

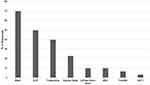

While 20 (67%) of the program directors reported incorporating MIGS into the surgical curriculum, only 8 (27%) thought MIGS training should be included in ACGME requirements for residency completion. 26 (87%) reported that 76–100% of glaucoma surgery was taught by fellowship trained glaucoma surgeons at their institution. Of the eight MIGS techniques listed, the most commonly reported techniques that were taught at residency programs were iStent (N = 21 or 70%), endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP) (N = 15 or 50%), and trabectome (N = 12 or 40%) (Figure 1). McNemar’s test revealed that iStent is taught more often than Kahook blade, Cypass Microstent, XEN implant, GATT, and Trab360 (p <0.01 for all). ECP was used more often than GATT and Trab360 (p <0.01 for both). There were no statistically significant regional variations in MIGS usage for iStent, ECP, or trabectome (p = 0.06, p = 0.46, p = 98, respectively).

|

Figure 1 MIGS techniques taught at residency programs. |

If residents performed a MIGS procedure as primary surgeon, the most common volume was 1–5 cases. The most common procedures residents performed as primary surgeons by graduation were iStent (N = 17 or 61%), ECP (N = 12 or 41%), trabectome (N = 10 or 36%), and Kahook blade (N = 4 or 14%) (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Number of Procedures Performed as Primary Surgeon by a Resident by Graduation |

Regarding exposure to MIGS cases, third year ophthalmology residents performed the greatest number of procedures as a primary surgeon, while first and second year residents mostly observed, and less frequently assisted with the procedures. More than 50% of residency program directors who answered the question indicated first and second year residents completed 0–5 MIGS procedures as primary surgeons. Nine (39%) of program directors reported that residents in their final year of training performed at least 5 MIGS procedures as primary surgeons.

In terms of location where MIGS procedures are performed, 16 (59%) and 11 (42%) program directors indicated the main facility/home institution and VA hospital, respectively.

The most common reported barriers to integrating MIGS into the residency curriculum, were: “current faculty not trained in MIGS” (N = 14 or 47%), “insufficient number of appropriate surgical candidates” (N = 11 or 37%), and “technology unavailable at our institution” (N = 10 or 33%).

Twenty-six (87%) program directors said residents received didactic training in MIGS and 22 (73%) indicated residents received wet lab training in MIGS. The most common techniques for which residents received wet lab training were iStent (N = 23 or 77%), trabectome (N = 8 or 27%), and Kahook blade (N = 5 or 17%).

Most program directors (11 or 37%) did not feel their residents’ MIGS experience was sufficient for them to be able to perform MIGS independently by graduation. However, 9 (30%) program directors did report being somewhat confident, 7 (23%) were slightly confident, 2 (7%) were quite confident, and 1 (3%) was extremely confident with resident ability to perform MIGS independently.

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated a decline in trabeculectomy cases and increase in glaucoma drainage device implantation over the past 10 years.5–10 Simultaneously, there has been an increase in development and use of MIGS devices.2,11 MIGS is becoming an important part of the surgical armamentarium for glaucoma surgery. However, their role and priority in residency education is unclear. This survey evaluated current resident experience with MIGS along with program directors’ attitudes regarding the importance of teaching this category of ophthalmic surgery.

In this survey study, it was encouraging to find that most programs incorporate MIGS into their surgical curriculum and provide both didactic and wet lab training. Of the MIGS techniques listed, all were reported as having been taught by at least one program. iStent was the most commonly taught MIGS procedure across all responders. ECP and trabectome were the next two most commonly taught procedures. Most residents were trained in MIGS by fellowship trained ophthalmologists.

The survey data suggests that residents in their final year gain some experience performing MIGS as primary surgeon, while junior residents gain exposure through observing and assisting. More MIGS procedures were performed at the home institution than the VA hospital. This contrasts with a study by Golden et al, which found only 38% of residents performed traditional glaucoma surgeries almost exclusively at their main facility, while 60% of residents reported performing some or all glaucoma surgeries at a VA site.12 Despite these experiences, most program directors did not feel their residents’ experience was sufficient for them to perform these procedures independently by graduation.

Several potential factors were listed as barriers to integrating MIGS into the residency curriculum, the most common being lack of faculty trained in MIGS procedures, lack of appropriate surgical candidates, and lack of available technology. These reported barriers may contribute to low adoption of MIGS at the institutions from which responses were received. Additionally, it may reflect less awareness about more affordable MIGS options such as 23 gauge cystotome goniotomy. As MIGS are more widely adopted, with more long-term studies published, and with establishment of well-defined applications for MIGS, these barriers may disappear. At that point, resident experience with MIGS may become more standardized across training programs.

Interestingly, few program directors felt MIGS should be included in ACGME requirements. While MIGS has not been added to the ACGME requirements to date, it is encouraging to see that the recent revisions the ACGME made to the Ophthalmology Milestones address more specific glaucoma surgery skills, such as the ability to manage complex post-operative complications including blebitis and tube erosion. The Milestones also include consideration of novel procedures. In the section, “Medical Knowledge 3: Therapeutic Interventions,” one of the milestones added includes resident ability to “describe and articulate the rationale for using novel alternative procedural interventions.”13 While this may not explicitly be interpreted to mean MIGS, it acknowledges that there are novel procedural interventions in ophthalmology and perhaps is a step in the direction of one day including MIGS in the ACGME requirements.

Limitations of this study include a low response rate (25%). However, it is comparable to that of the historical control survey on glaucoma practice patterns by Vinod et al (23% response rate)7,8 and responses were received from all geographic regions of the country. Another limitation is that the survey design did not allow for the distinction between 0 and 1–5 cases for the questions about number of cases residents observed, assisted, and completed as primary surgeons. Thus, we cannot accurately quantify if residents did not observe, assist, or complete MIGS procedures at all.

Additionally, since the study was performed, MIGS have further evolved with the introduction of new devices such as an iStent inject and Hydrus, and their usage in resident education was not assessed. Cypass was withdrawn from the market in 2018 due to safety concerns, and therefore experience with this device is no longer applicable. Despite these changes, the findings of our study offer insight into MIGS education in US ophthalmology residency programs. Furthermore, the advent of newer MIGS may provide options that are more adaptable for surgeons and will gain further popularity. As with the adoption of any new technology, caution should be exercised, and regular review of current literature is necessary to stay informed of any concerning trends with new device usage.

With the growing popularity of MIGS, familiarity with these techniques is important, especially given many MIGS procedures are approved for use in combination with cataract surgery and are being performed by glaucoma and cataract surgeons alike. Most graduating residents are likely to encounter cataract patients that may benefit from a combined cataract MIGS procedure in independent practice. Therefore, at the very least, exposure and familiarity with these therapeutic options is critical to maintaining high quality ophthalmic care.

Conclusion

Results of this study may better inform ophthalmology educators about the current trends in MIGS training and help guide curriculum development in ophthalmic surgical education. While this study was specific to ophthalmic minimally invasive surgical techniques, the findings of the study may be informative to other surgical training programs, whose fields have been expanded to include novel surgical techniques, which currently have not been incorporated into the ACGME case logs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Saheb H, Ahmed IIK. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery: current perspectives and future directions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(2):96–104. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834ff1e7

2. Minckler D. Microinvasive glaucoma surgery: a new era in therapy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2016;44(7):543–544. doi:10.1111/ceo.12815

3. Francis BA, Singh K, Lin SC, et al. Novel glaucoma procedures: a report by the American academy of ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2018;118(7):1466–1480. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.03.028

4. United States Census Bureau. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

5. Chadha N, Liu J, Maslin JS, Teng CC. Trends in ophthalmology resident surgical experience from 2009 to 2015. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1205–1208. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S106293

6. Chadha N, Liu J, Teng CC. Resident and fellow glaucoma surgical experience following the tube versus trabeculectomy study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(9):1953–1954. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.009

7. Desai M, Gedde S, Feuer W, Shi W, Chen P, Parrish R

8. Vinod K, Gedde SJ, Feuer WJ, et al. Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery: a survey of the American glaucoma society. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(8):687–693. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000720

9. Ramulu PY, Corcoran KJ, Corcoran SL, Robin AL. Utilization of various glaucoma surgeries and procedures in medicare beneficiaries from 1995 to 2004. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(12):2265–2270.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.005

10. Arora KS, Robin AL, Corcoran KJ, Corcoran SL, Ramulu PY. Use of various glaucoma surgeries and procedures in medicare beneficiaries from 1994 to 2012. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1615–1624. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.015

11. Gedde SJ, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ, Herndon LW, Brandt JD, Budenz DL. Three-year follow-up of the tube versus Trabeculectomy Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):670–684. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.018

12. Golden RP, Krishna R, DeBry PW. Resident glaucoma surgical training in United States residency programs. J Glaucoma. 2005;14(3):219–223.

13. ACGME. Ophthalmology milestones. ACGME Report Worksheet. January, 2020. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/OphthalmologyMilestones2.0.pdf?ver=2020-01-17-145640-583.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.