Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 12

Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia with bone marrow infiltration: a case report and literature review

Authors Zhang Y, Luo L, Wang X, Liu X, Wang X, Ding Y

Received 23 February 2016

Accepted for publication 13 April 2016

Published 14 June 2016 Volume 2016:12 Pages 975—981

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S107012

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Deyun Wang

Yunjian Zhang,1 Ling Luo,1 Xiaofang Wang,1 Xiaoyang Liu,1 Xiaoyan Wang,1 Yi Ding2

1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, 2Department of Pathology, Jishuitan Hospital, Fourth Medical College of Peking University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Abstract: Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia has been rarely reported. We reported a case of mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a 56-year-old female who took mesalazine without a prescription for suspected ulcerative colitis. She had an elevated eosinophil count in peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Eosinophil infiltration was also noted in bone marrow aspirates. Chest radiograph and computed tomography demonstrated bilateral upper lung predominant infiltrates and spirometry showed a restrictive ventilatory defect with a reduced diffusion capacity. The patient recovered after cessation of mesalazine therapy. Mesalazine-induced lung damage should be considered in patients who develop unexplained respiratory symptoms while taking this agent.

Keywords: mesalazine, pneumonia, eosinophil, colitis

Introduction

Mesalazine and other 5-aminosalicylate agents remain the current standard of care for inducing remission in mild-to-moderate active ulcerative colitis. Pulmonary toxicity secondary to mesalazine is very rare due to its lack of sulfapyridine moiety. Eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by an abnormal accumulation of eosinophils in the lung, but apart from secondary causes, such as infection and medication, its etiology remains unknown. Though scattered case reports of mesalazine-associated interstitial lung diseases, such as organizing pneumonia, broncholitis obliterans, and interstitial lymphocytic pneumonia, are available,1–6 mesalazine-associated eosinophilic pneumonia has been sparsely reported.7–10 We report a case of eosinophilic pneumonia in a woman who took mesalazine for suspected ulcerative colitis and also carry out a literature review of reported cases of mesalazine-eosinophilic pneumonia.

Case report

This study was approved by the review boards of Jishuitan Hospital and Fourth Medical College of Peking University. Patient consent to this study was not required because the retrospective nature of the study. A 56-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital on July 1, 2015 because of intermittent fever and nonproductive cough for 2 weeks and exertional dyspnea and chest pain for 1 week. She described no chills, rigors, and night sweats. The patient developed abdominal pain and had mucus stools on April 20, 2015. Laboratory tests at a local clinic on May 20, 2015 showed leukocytes at 6.9×109/L with 67.9% neutrophils and 0.12% eosinophils. Her hemoglobin level was 129 g/L and platelet count was 276×109/L. The occult stool test was weakly positive. She started mesalazine 0.5 g three times a day for 6 weeks without a prescription. The patient began coughing on June 17, 2015 and also had fatigue and fever (as high as 39.4°C). Laboratory examinations revealed leukocytes at 12.75×109/L with 76.2% neutrophils and 6.9% eosinophils. Her hemoglobin level stood at 124 g/L and platelet count was 485×109/L. A chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT) scan showed minor peripheral patchy opacity in bilateral upper and mid lungs with a narrowed right costophrenic angle (Figure 1A and B). A 10-day course of intravenous levofloxacin and ceftazidine was administered, and the patient continued mesalazine. Nevertheless, the patient was still febrile. On June 24, 2015, the patient developed right chest pain and aggravating exertional dyspnea. She denied symptoms of palpitations and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. She denied the use of tobacco products and had no occupational exposure to chemical fumes, including biomass fuel. The patient was allergic to penicillin and metronidazole. She had hypertension for 5 years, which was controlled by taking sustained release nifedipine. There was no family history of asthma.

Physical examination at admission showed a blood pressure of 117/70 mmHg, a pulse rate of 101 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and a temperature of 37.4°C. No crackles were noted in both lungs. Clubbing, cyanosis, or peripheral edema was absent. Cardiovascular and abdominal examinations were unremarkable. Review of the systems was unremarkable for skin rashes, joint pain, and weight loss.

Laboratory investigations revealed leukocytes at 25.54×109/L with 67.4% neutrophils and 21.8% eosinophils. Her hemoglobin was 111 g/L and platelet count 593×109/L. Renal and liver function were normal, and no splenomegaly was noted. Chest radiograph showed progressing opacity predominantly in bilateral upper lungs (Figure 1C). Chest CT scan revealed bilateral patchy consolidations with interlobular septal thickening (Figure 1D and 1E). The single-breath diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) was 46% of the predicted values. Transbronchial biopsy revealed chronic inflammation and exudation of fibrin (Figure 2A), and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) showed 1×109 cells/mL with 18% macrophages, 22% neutrophils, 33% eosinophils, and 27% lymphocytes (Figure 2B). Bone marrow aspirate showed infiltration by mature eosinophils (Figure 2C), but the ratio of promyelocytes to their precursors was normal, and the percentage of eosinophils was 18, with normal morphology. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.523, a partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) of 29.7 mmHg, a partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) of 59.5 mmHg, and a bicarbonate level of 23.2 mmol/L on room air. Tests for adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, seasonal influenza A and B, parainfluenza virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia, and Legionella pneumophila were negative. Tuberculin skin test and sputum and BALF tests for acid-fast bacilli excluded tuberculosis. Rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, anti-double-strand DNA antibody, antiextractable nuclear antigen antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative. C-reactive protein was at 191 mg/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate was at 65 mm/h, and immunoglobulin E was at >100 IU/mL. Colonoscopy at 2 weeks after admission demonstrated focal erythema, erosions, and edematous swollen mucosa in the rectum.

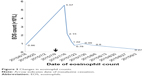

Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia was diagnosed, and mesalazine was discontinued. Currently, there is no consensus for the use of corticosteroid therapy for mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia, and our patient was not given corticosteroids. Besides, four out of nine reported cases also recovered without corticosteroid therapy. The patient improved in symptoms, and 4 weeks after cessation of mesalazine, she was discharged. CT scan showed bilateral ground glass opacity (Figure 1E). At 5 weeks of follow-up after discharge, the patient was asymptomatic with a normalized eosinophil count (Figure 3). Spirometry continued to show a restrictive defect and a reduced DLco (44%) (Table 1), but the patient felt no apparent exertional dyspnea after discharge.

| Figure 3 Changes in eosinophil counts. |

Discussion

Eosinophilic pneumonia is characterized by eosinophilic infiltration in the lungs, radiographic abnormalities, impaired lung function, and peripheral blood eosinophilia. The causes of eosinophilic pneumonia remain largely unknown, and the disease may occur secondary to medications, such as mesalazine. We describe a case of eosinophilic pneumonia in a woman who took mesalazine for proctitis. The case was confirmed by clinical manifestations, medication history, BALF cytology, and radiological findings. The case is noted for eosinophilia in peripheral blood and for infiltration of mature eosinophils in the lungs and the bone marrow. Though it has not been reported in mesalazine-associated eosinophilic pneumonia, eosinophil infiltration in the bone marrow due to other drugs, such as minocycline, has been described.11

The first case of mesalazine-induced lung hypersensitivity was reported in 1991.12 Over the past two decades, several cases of mesalazine-induced pulmonary toxicity have been reported, particularly eosinophilic pneumonia.7,9,13–19 The incidence of lung disease from mesalazine is unknown; however, reports from mesalazine-induced lung disease have increased, and the pathogenesis is still unknown.8 Immune-mediated injury and direct cytotoxic effect are considered as causes of drug-induced lung injury.

Symptoms related to mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia can range from being asymptomatic to fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Women were reported to be affected more often than men.6 Among nine previously published case reports of mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia, there were three males13,16,17 and six females7,9,14,15,18,19 with a mean age of 34 years (ranging from 23 years to 50 years). Most cases occurred between 1 month and 7 months after the initiation of the drug, with rare cases occurring 2 years later.7,9,13–19 The clinicopathologic and radiologic features of these patients and our patient are summarized in Table 2.

The diagnosis of mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia can be challenging. Laboratory tests may reveal peripheral eosinophilia. Eosinophilia in peripheral blood was found in all nine patients previously reported with eosinophils ranging from 16% to 63%.7,9,13–19 Arterial blood gas can show hypoxia. Pulmonary function tests usually demonstrate a restrictive picture with a reduced diffusing capacity as seen in our case. Nonspecific interstitial infiltrate or consolidation is usually seen in the chest radiograph or CT scan. In some cases, characteristic finding described as wandering shadow is observed.7,16 If the diagnosis remains unclear, bronchoscopy and BAL should be performed. The BAL frequently shows an elevated count of eosinophils, while transbronchial lung biopsy may reveal interstitial infiltrates or alveolar exudates. Preferably, the presence of eosinophilia in peripheral blood, BAL, or lung tissue should be used as indicators for diagnosing mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in patients with a medication history of mesalazine.

The most essential aspect of diagnosing mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia is a high index of suspicion. A detailed history and laboratory and diagnostic studies can help to distinguish inflammatory bowel disease-associated lung involvement from mesalazine-related toxicity. In the present patient, it is reasonable to establish a diagnosis of mesalazine-induced pneumonia for several reasons: 1) the appearance of respiratory symptoms during drug therapy; 2) clinical, radiological, and BALF findings consistent with mesalazine-induced eosinophilic lung disease; 3) the absence of established criteria required for diagnosing inflammatory bowel disease; 4) other lung diseases, such as those due to infections, were excluded; 5) clinical and radiological improvements after mesalazine discontinuation.

The most important aspect of treatment involves discontinuation of therapy with mesalazine. Mesalazine cessation usually leads to improvement in both clinical and radiographic pictures. The role of steroids for mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia is unclear. Corticosteroid therapy can lead to rapid recovery. However, several reports also describe full recovery after discontinuation of mesalazine without steroid therapy.7,15,16,19 Our patient also markedly improved by simple cessation of mesalazine intake. The prognosis of mesalazine-induced lung injury is good.

One limitation of this report is that transbronchial biopsy failed to detect infiltration by eosinophils in the lung tissues of the patient. This is probably due to the small area of lung tissues that can be biopsied via the transbronchial approach. The biopsy site may not be representative of lesions characteristic of eosinophilic pneumonia. It remains to be seen whether increasing the number of biopsies at multiple sites would lead to a higher rate of positive finding.

Conclusion

Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia is an extremely rare entity. Clinical and imaging manifestations are not specific. The diagnosis is relied on the history of mesalazine therapy, eosinophilia in blood, pulmonary histiocytic infiltration with eosinophils, and marked improvement of symptoms and radiologic abnormalities after the discontinuation of mesalazine. The possibility of drug-induced eosinophilic pneumonia should be fully considered in patients developing unexplained respiratory symptoms while on mesalazine therapy.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Project of Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z141107002514153).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Michy B, Raymond S, Graffin B. Pneumopathie organisée apparue sous mésalazine [Organizing pneumonia during treatment with mesalazine]. Rev Mal Respir. 2014;31(1):70–77. | ||

Shindoh Y, Horaguchi R, Hayashi K, Suda Y, Iijima H, Shindoh C. [A case of lung injury induced by long-term administration of mesalazine]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi/J Jpn Respir Soc. 2011;49(11):861–866. Japanese. | ||

Đurić M, Považan Đ, Sečen S, Jović J. Differential diagnosis problem of pulmonary changes in ulcerative colitis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2010;67(6):511–514. | ||

Taguchi S, Furuta J, Ohara G, Kagohashi K, Satoh H. Severe airflow obstruction in a patient with ulcerative colitis and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9(5):1944–1946. | ||

Haralambou G, Teirstein AS, Gil J, Present DH. Bronchiolitis obliterans in a patient with ulcerative colitis receiving mesalamine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68(6):384–388. | ||

Sossai P, Cappellato MG, Stefani S. Can a drug-induced pulmonary hypersensitivity reaction be dose-dependent? A case with mesalamine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68(6):389–395. | ||

Tanigawa K, Sugiyama K, Matsuyama H, et al. Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia. Respiration. 1999;66(1):69–72. | ||

Inoue M, Horita N, Kimura N, Kojima R, Miyazawa N. Three cases of mesalazine-induced pneumonitis with eosinophilia. Respir Investig. 2014;52(3):209–212. | ||

Kim JH, Lee JH, Koh ES, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia related to a mesalazine suppository. Asia Pac Allergy. 2013;3(2):136–139. | ||

Franco AI, Escobar L, Garcia XA, et al. Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a patient with ulcerative colitis disease: a case report and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31(4):927–929. | ||

Bentur L, Bar-Kana Y, Livni E, et al. Severe minocycline-induced eosinophilic pneumonia: extrapulmonary manifestations and the use of in vitro immunoassays. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31(6):733–735. | ||

Le Gros V, Saveuse H, Lesur G, Brion N. Lung and skin hypersensitivity to 5-aminosalicylic acid. Br Med J. 1991;302(6782):970. | ||

Ferrusquía J, Pérez-Martínez I, Gómez de la Torre R, et al. Gastroenterology case report of mesalazine-induced cardiopulmonary hypersensitivity. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(13):4069–4077. | ||

Fayaz M, Sultan A, Nawaz M, Sultan N. Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic variant of Wegener’s granulomatosis in an ulcerative colitis patient. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21(4):171–173. | ||

Shimizu T, Hayashi M, Shimizu N, Kinebuchi S, Toyama J. [A case of mesalazine-induced lung injury improved by only discontinuation of mesalazine]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi/J Jpn Respi Soc. 2009; 47(6):543–547. Japanese. | ||

Park JE, Hwangbo Y, Chang R, et al. [Mesalazine-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a patient with Crohn’s disease]. Korean J Gastroenterol/Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe chi. 2009;53(2):116–120. Korean. | ||

Hakoda Y, Aoshima M, Kinoshita M, Sakurai M, Ohyashiki K. [A case of eosinophilic pneumonia possibly associated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi/J Jpn Respir Soc. 2004; 42(5):404–409. Japanese. | ||

Zamir D, Weizman J, Zamir C, Fireman Z, Weiner P. [Mesalamine-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis]. Harefuah. 1999;137(1–2):28–30, 87, 86. Hebrew. | ||

Honeybourne D. Mesalazine toxicity. Br Med J. 1994;308(6927):533. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.