Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 13

Male Nurses’ Dealing with Tensions and Conflicts with Patients and Physicians: A Theoretically Framed Analysis

Authors Mao A , Wang J, Zhang Y, Cheong PL , Van IK, Tam HL

Received 9 July 2020

Accepted for publication 11 August 2020

Published 29 September 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 1035—1045

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S270113

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Video abstract of "Male nurses’ dealing with tensions and conflicts" [ID 270113].

Views: 175

Aimei Mao,1 Jialin Wang,2 Yuan Zhang,3 Pak Leng Cheong,1 Iat Kio Van,1 Hon Lon Tam1

1Kiang Wu Nursing College of Macau, Macau, People’s Republic of China; 2College of Nursing, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Nursing, Neijiang Health Vocational College, Neijiang, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Jialin Wang

College of Nursing, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1166 Liutai Road, Wenjiang District, Chengdu, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86 2861800057

Email [email protected]

Proposes: Delivery of healthcare involves engagements of patients, nurses and other health professionals. The Social Identity Theory (SIT) can provide a lens to investigate intergroup interactions. This study explores how male nurses deal with intergroup tensions and conflicts with patients and physicians when delivering healthcare.

Methods: A collaborative qualitative research study was conducted by two research teams, with one from Mainland China and the other from Macau. Twenty-four male nurses were recruited, with 12 from each of the two regions. A similar guide was used by the two teams to conduct in-depth interviews with the participants. Thematic analysis was used, and SIT guided the data analysis and interpretation of the results.

Results: Four themes identified are related to nurse/patient relationships: respecting patients’ decisions, neglecting minor offenses, defending dignity, taking a dominant position; two themes are related to nurse/physician relationships: rationalizing physicians’ superiority over nurses, establishing relationships with physicians by interpersonal interactions.

Conclusion: Male nurses avoid confrontation with patients in case of disagreements but take on gender- and profession-based dominance in dealing with intense conflicts to maintain healthcare order. They do not challenge the status hierarchy between nurses and physicians but manage to maintain harmonious relationships with physicians by engaging in interpersonal activities with physicians in leisure times.

Implication: Male nurses can take the lead to create inclusive groups to engage patients and physicians in delivering healthcare. The masculine traits of male nurses do not subvert the nurse/physician hierarchy stereotype but strengthen it.

Keywords: male nurses, gender, intergroup, patients, physicians, Social Identity Theory

Plain Language Summary

Relationships between patients and healthcare providers are vital for the quality of healthcare. In previous times, the relationships were described as the paternalist style of care in which the healthcare providers made decisions and the patients were expected to follow the providers’ instructions. Modern healthcare has advocated a patient-centered model in which healthcare providers work closely with patients and value patients’ decisions. Furthermore, physicians traditionally take a leadership role in the interactions between physicians and nurses because physicians are usually males and nurses are generally females. Such unequal social status between physicians and nurses reflects the unequal social status between males and females in the broad society. Now that an increasing number of males join the nursing profession, there is a need to learn the way male nurses interact with physicians. In healthcare contexts, teams or groups influence interactions of the individual members of the groups. In this study, we applied the Social Identity Theory (SIT) to explore male nurses’ dealing with tensions and conflicts with patients and physicians because this theory is useful to examine intergroup interactions. We invited male nurses in both Macau and Mainland China, the two regions with different social-economic conditions. We reported interesting findings on gender- and power-influenced intergroup dynamics among male nurses, physicians, and patients.

Introduction

Relationships between patients and healthcare providers are vital for the quality of healthcare. In previous times, the relationships were described as the paternalist style in which healthcare providers took a dominant role.1 The paternalist style of the healthcare model tended to place patients as opposed to healthcare providers. Research on male nurses reported female patients’ decline of intimate care from male nurses,2 and pieces of news occasionally reported assaults committed by male nurses to their patients.

Modern healthcare has advocated a patient-centered model in which patients become empowered in decision making. They are treated as part of the healthcare team and are encouraged to actively take part in treatment planning.3 Recent studies reported the increasing acceptance of male nurses’ services from patients.4,5 Some patients even felt more comfortable with male nurses’ services than those of female nurses.4,5 However, studies from the Middle East revealed the still prevailing discrimination against male nurses in the Arab world.6,7 The different attitudes towards male nurses from patients in different cultures imply the need for exploration of male-nurse/patient interactions in different cultural contexts.

Further, previous research discussed the nurse/patient interactions from an interpersonal perspective. For example, Peplau’s well-known theory on interpersonal relationships discusses the skills nurses should take to build therapeutic relationships in different stages of nurse/patient encounters.8–10 As a result, research on nurse/patient relationships has focused on nurses’ communication skills, such as lack of empathy for patients, neglect of patients’ needs, insufficient time contributed to patients’ bedsides, etc.11,12 Such personal- focused analysis has missed the social contexts of the interactions. Given that patient care is the target of teamwork, individual nurses and patients are the team members, and analysis of nurse/patient dialogue should be taken under the team or group context.

Nurses work with physicians daily, and their relationships are well known to be unequal, with physicians exhibiting superior over nurses. There are disrespected behaviors from physicians, such as intimidating and abusing nurses.13–15 Despite the inequality, few studies have explored the underlying contributors to the inequality, as this phenomenon has been taken for granted.16 It is supposed that the physician/nurse power hierarchy is attributed to the gendered power hierarchy in the broader society, because nurses have historically been females, with physicians being males.17 Now that males are joining the nurse population, how male-nurse/physician power dynamic influences the nurse/physician hierarchy is a field under-investigated.

SIT Perspective

SIT is part of individuals’ self-concept derived from perceived membership in a relevant social group. It is built on three cognitive processes: social categorization, social identification, and social comparison.18,19 Social categorization is a process in which individuals categorize themselves into social groups. For example, a young man can belong to a nursing school, a football team, or a guitar club. Individuals divide the world into “us” (ingroup) and “them” (outgroup) by categorizing themselves and others. Social identification is the process in which people adapt to the groups they belong to and behave in line with the groups’ collective norms and practices. For example, if a woman perceives herself as a nurse, she would adopt the nursing profession’s values, attitudes, and norms. People tend to hold emotion to ingroup and outgroup, depicted by their positive attitudes towards ingroup and negative attitudes towards outgroups.18 Social comparison is a process in which ingroup members make comparisons with other groups in terms of social standing and prestige. The social comparison provides group members with a sense of the distinctiveness of their groups and invokes their motivations to enhance the group status.18

SIT is instrumental in exploring intergroup interactions of the involved players. While this theory has been widely used in medical sciences,19–21 it is rarely applied in nursing science. Scholars have called for nurses’ attention to this theory because it can provide a valuable framework for exploring features of nursing professional identity in complicated structural and contextual conditions.22 Although SIT helps analyze both intra-group and intergroup processes, this study focuses on intergroup interactions. Intra-group interactions of nurse professionals possess unique features, and they deserve more detailed descriptions in future analyses. This study would answer two interrelated questions: How do male nurses develop partnerships with patients and physicians? How do they deal with tensions or conflicts with patients and physicians? Whereas nurses work as a team member for patients’ wellbeing, they have their interests and rights to defend when working with patients and physicians. The study was a collaborative one between Macau and Mainland China. Male nurses from both Macau and Mainland China were invited to this study.

The Social-Economic Differences Between Macau and Mainland China

Macau, also called Macao, is a special administrative region in China, together with Hong Kong. It enjoys much higher autonomy in governance than local governments in Mainland China. It is a developed economy with GDP per capita being 79,977 USD in 2019,23 compared to 10,276 USD in Mainland.24

Both Macau and the Mainland have honored nursing with a status of profession in the past two decades. Macau has stricter requirements for registration of nurses than the Mainland. It requires at least four years of bachelor’s degree education, while Mainland graduates from all kinds of nursing schools are eligible to sit for registration. More importantly, Macau’s nurses enjoy much higher payments than the average income level in the local region. Despite varied salaries in private institutes, the threshold monthly salary in Macau is around 38,000 MOP (around 4800 USD) for nurses in public health institutes, with extra reimbursement for working time in weekends and nightshifts;25 while in the Mainland, the national monthly salary is 5425 CNY (around 780 USD) for nurses, with nurses in under-developed regions, such as Hebei and Jiangxi Provinces, being paid less than 4000 CNY (around 570USD)26 a month. Nurses in China have complained the low payment all the time.27,28

By inviting participants from different social-economic conditions, the study can get in-depth knowledge of the underlying contributors to intergroup dynamics of nurse/patient and nurse/physician.

The Study

The Design and Participants

The data analyzed here are from a larger collaborative qualitative project on the development of the professional identity of nursing students and clinical nurses in Mainland China and Macau. Part of the project was to explore male nurses’ experience in professional identity construction. A collaborative contract was signed by the primary investigator of each of the two teams, designating responsibilities and rights of each team.

The criteria for participants were: 1) male registered nurses; 2) currently working as a nurse. Purposive and snowballing sampling was used to recruit the participants. Different backgrounds of the participants were considered to maximize a heterogeneous sample, such as the health institutes or departments employed, the length of time working as a nurse, marital status, etc. As all the researchers on the two teams, except one postgraduate student, were nursing teachers, they used their connections to find the potential participants. Also, current participants were asked to introduce new participants. The researchers approached the potential participants in person or by telephone and explained the purpose of the study. Upon initial approval was obtained, an interview schedule was made to the mutual convenience of participants and researchers.

Twelve participants from the Mainland joined the study. They were from the hospitals in Chengdu, the capital city of the western China province of Sichuan. The city is the largest one in western China, with a population of 20 million. Hospitals in China are ranked at different levels by the governments, according to their scale, equipment, technology, etc. The males came from six Grade 3A hospitals, the highest-ranking of hospitals in China. Among the six hospitals, five were civilian hospitals, and the other one was a military hospital. The Macau team recruited the same number of participants. They came from various health institutes, including public and private health institutes. The characteristics of the participants are in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Characteristics of the Male Nurse Participants (N=24) |

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with the 24 participants. Each team did 12 interviews in its region. The two teams developed an interview guide based on the literature review and the researchers’ clinical nursing experience. The guide was relatively loose, allowing flexibility for the researchers to probe based on emerging themes. Before interviewing, around 15 minutes was offered for the participants to read through the consent form and sign. The interviews served the aims of the project, covering the participants’ views on being a male nurse, the events or persons that impacted their professional identity development, the difficulties and challenges they encountered and their coping ways. The interviews from Macau lasted 49 minutes on average, and those from the Mainland lasted 58 minutes averagely.

Data Analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded under permissions from the participants. They were transcribed verbatim. Inductive analysis was applied as this technique allows researchers to identify themes and categories from raw data.29 SIT guided the analytic process in which the researchers explored how male nurses categorized themselves as members of the nurse group and behaved in line with the norms and values of the group. Particularly, the theoretical framework guided exploration of group interactions among patients, physicians, and male nurses, with male nurses in the center of the interaction network.

All the researchers shared data from the two teams. The team in Macau initiated and directed the data analysis. They developed a coding framework and got consensus from the team in the Mainland. The two sides did the coding of the data and kept frequent contacts throughout the analytical process via WeChat online instant discussions. The qualitative research data software, NVivo 11 Plus, was used to facilitate the data analysis.

Ethical Consideration

The two teams got research approval from their respective academic institute. The team in Macau got permission from the Research Committer of Kiang Wu Nursing College of Macau (Reference no: 2016JAN01). The team in the Mainland obtained approval from the Research Committer in Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the approval was made public (https://sedrcihe.cwnu.edu.cn/info/1077/1898.htm, reference no: CJF19019). The participants were assured of their rights to voluntary participation. Confidentiality for personal information was assured. A consent form was signed by the participants before the interviewing was conducted and the informed consent included publication of anonymized responses.

Trustworthiness

Several measures were taken by the researchers to ensure the trustworthiness of the study. Firstly, the collaborative research design enhanced the rigor of the study. The two research teams recruited a diverse sample of participants from both Macau and Mainland China. The viewpoints and experiences of the participants from different social-economic contexts enhanced the richness of the data. Secondly, the researchers were registered nurses in Macau or in Mainland, and one of them was a frontline male nurse. The similar background between the participants and the researchers helped the research processes in interviewing and data analysis. Thirdly, member check is a way to improve study credibility,30 and in this study, member check was done by sending the analytic results back to several of the participants to get their feedback.

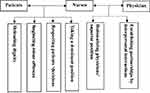

Results

Among the 24 male nurses, one worked in a community health center; one worked in a large clinic, while the other 22 worked in hospitals. Working with patients and physicians was the daily life for the clinical nurses, and the participants constantly described their relationships with patients and physicians as “co-operators” and “partners.” Guided by the SIT, the researchers looked into not only the collaborations between nurses and the other two players in the healthcare team but also the tensions and conflicts among them. The nurses needed to get over group boundaries to work with patients and physicians; on the other hand, they needed to keep the ingroup distinctiveness of nurses and defend the interests of their group. The intergroup interactions of nurse/patient and nurse/physician can be illustrated in a series of themes. Four themes are related to nurse/patient interactions, and two are related to nurse/physician interactions (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 The patterns of nurse/patient and nurse/physician intergroup interactions. |

In the following sections, the Macanese male nurses are referred to as MMN, and the (Mainland) China male nurses are referred to as CMN. They are numbered according to the order to join the study. For example, the first male to enter the study was numbered as “1”.

The Nurse/Patient Intergroup Interactions

Gender influence was permeated as the male nurses stated gender-related advantages or disadvantages in healthcare. However, the male nurses emphasized that patients judged nurses not based on their sex, but the quality of healthcare provided by the nurses. When nurses had trust from their patients, a harmonious relationship was built between the two. The male nurses generally enjoyed harmonious relationships with their patients. Tensions and even conflicts did happen now and then, particularly in Mainland China. Gendered dynamics shaped the intergroup interactions between male nurses and their patients.

Respecting Patients’ Decisions

As reported in other studies,2 the male nurses in the two regions all had experienced service decline from their female patients, although this only happened several times in a year. The service limitation had, in turn, confined the male nurses to work in a limited number of wards where there might be fewer chances of service refusal, such as ER, OR, ICU, etc., as shown in Table 1. Most of the male nurses expressed their understanding of the patients’ feelings and did not get annoyed. MMN 5 had worked in ICU for five years. He was once hospitalized and needed surgery. He asked a male nurse to serve him:

I was in the OR and waited to have the Urethral Catheterization. One of the female colleagues joked to me: ‘Are you ready to have the Catheterization? I’ll begin.’ I said to her: ‘No, get a guy for me!’. If I were not a nurse in the hospital and had not known the nurses in the OR, I might not have had the choice, because I had already laid in the bed and had the anesthesia. You cannot say that the patients are picky. They just feel more conformable with the same sex nurses to do some procedures for them. I suppose they feel the same as I did at that time.

MMN 5 showed empathy with patients who chose to have same-sex nurses to do nursing care. This empathy was shared by other male nurses who would let patients choose male or female male nurses if the nursing care involved the intimate contact of the body.

Neglecting Minor Offenses

Male nurses sometimes ridiculed their female colleagues who wept over annoyances from patients. For example, patients complained that the nurses had overcharged their medical fees or complained that the nurses were not quick enough to respond to their request. In the male nurses’ eyes, the annoyances were negligible. Compared with females, male nurses regarded themselves as more broad-minded. They were less likely to be troubled by trivial wrongdoings made by themselves and others. MMN3 had worked in the ER for one year and he spoke of the gendered differences of personalities:

Males do not pay much attention to the trivial, but females do. So females sometimes have conflicts with other people over the trivial. There are many many little things each day. We do not care too much about them, whether they are done correctly or incorrectly. Everyone has his or her way of doing things.

Defending Dignity

According to the male nurses, there were disagreements between nurses and patients now and then, and they were usually not bothered by the disagreements. On the other hand, male nurses seemed to have a redline where patients could not cross. Otherwise, they would vigorously defend themselves against the patients. CMN2, who had worked as a nurse in ICU for five years and was now the head of one of the two nurse groups in the ICU, vividly described a nurse/patient conflict:

It happened when I was in rotation as a new nurse in an internal medicine ward. One patient got angry with us, saying that we charged too much money on her. She and her daughter quarreled with us in our nursing station. Then I heard her daughter make a phone call, saying to the phone that the ‘son of bitches’ was bullying them two. I approached the daughter, warning her, ‘Lady, please pay attention to your words! If you are still rude, I will get you out of the door!’ She stared at me, ‘Who are you? I will make a complaint to your hospital head!’ I showed her my employee card and said, ‘This is my name. Go and make the complaint!’ I welcome patients who come to discuss disagreements with us. But I cannot tolerate the insults to us.

Another male nurse in the Mainland also described an intense conflict between nurses and a male patient in a ward. As the patient made gestures to beat his female colleagues, the male nurse said, “Let’s go out of the ward. I will take off my uniform, and let’s fight outside of the hospital!” (CMN 10, who was a staff nurse and had worked in ICU for three years). By suggesting going outside of the hospital, this male nurse implied that the upcoming fight between him and the male patient was the interpersonal event, not professional related behavior. He did so to protect the image of nurses and his hospital.

Strong conflicts between nurses and patients seemed to happen in the Mainland more often than in Macau. Some of the male nurses in Macau had once practiced in the Mainland as part of nursing training and were impressed by the strained patient/healthcare provider relationships. MMN9, who once went to study in hospitals in the Mainland, offered his opinion on the strain of nurse/health provider relationships, Overall the patient/healthcare provider relationships are not good in Mainland. Perhaps this is because of the policies which induce hospitals there to try their best in economic gains. He continued to elaborate that, nurse/patient relationships were adversely impacted by the overall strained patient/healthcare provider relationships, The patients lost trust in physicians. They think that physicians tend to prescribe lots of tests and medications, which may not be necessary for patients. They do this for money. The nurses are the accomplice of physicians. The account implies that the strained relationships between patients and healthcare providers were attributed to China’s overall health system failures.

Taking a Dominant Position

The male nurses repeatedly stated their relationships with their patients as equal partnerships. However, in certain circumstances, when conflicts arose and disturbed the healthcare arrangements, the male nurses tended to control the situation in a demanding way. MMN19 had worked in a HU for three years, and he talked about male nurses’ gendered advantage in getting cooperation from patients.

We sometimes ask patients to move beds because of bed arrangement changes. Our female colleagues make the request softly, and one or two patients think that they can bargain, ‘Why me? Ask someone else!’. The female colleagues may come to me for help because I am a man. I would go over and make demanding, ‘You have to move. There is no choice for you!’ As male nurses, we can naturally create a controlling atmosphere when standing in front of patients, so the patients often follow our demands.

In this case, masculine played a role in controlling the problematic situation. Other males also recalled that their female colleagues “were bullied” by male patients and sought male colleagues’ help.

The Nurse/Physician Intergroup Interactions

Contradictions existed with the male nurses’ accounts on their relationships with physicians. On the one hand, they described the partnership with physicians and that nurses and physicians respected each other. On the other hand, they acknowledged the unequal social and professional positions between the two. There are two themes related to the nurse/physician intergroup interactions: rationalizing physicians’ superiority over nurses and establishing partnerships through interpersonal interactions.

Rationalizing Physicians’ Superiority Over Nurses

The male nurses acknowledged that physicians enjoyed a higher social status than nurses and accepted the fact. The visible symbol of inequality between nurses and physicians was the payment differential between the two. CMN 8, who had worked in the OR for two years, mentioned the payment differences,

The director of OR once told us: ‘Why should physician get more bonuses than nurses? Because they have had several years more in medical education than nurses’.

The male nurses in the two regions all accepted that higher education of physicians than nurses was reasonable for their higher payment. Also, shorter nursing education was regarded as an advantage for nurses because nurses could provide financial support for their families after a relatively shorter time of education.

The male nurses also mentioned more responsibilities with physicians, as CMN 8 said,

With the current model, I think physicians play a more important role than nurses in patient care. This is because nurses cannot make decisions on many aspects. I don’t think nurses have practiced to their full potentials.

Macanese male nurses echoed his account:

Physicians decide what to do; nurses then do, and they decide how to do. So, physicians bear greater responsibilities than nurses. Nurses instruct nursing assistants on what to do, and the assistants decide how to do it. These are responsibility divisions. You may say there is a hierarchy here. It is true. (MMN9, who had worked in the ER for three years)

According to MMN9, hierarchy existed in different layers of the healthcare systems, and physicians seemed on the top of the hierarchy. While nurses had a lower status than physicians, they had higher status than nursing assistants. Male nurses observed that some of their female colleagues were dissatisfied with the lower status of nurses. However, they did not bother by the status inequality:

Some of the physicians and nurses are dissatisfied with each other. This is because of the way of communication between the two. These nurses feel that physicians are giving their orders, and they feel unfair, ‘Why should I follow your order? What justify you give nurses order?’ I do not mind the physicians’ orders. It is the work divisions between physicians and nurses. (CMN5, who had worked in ICU for seven years and was the head of one of the nurse groups in ICU)

This male disagreed with the way of his female colleagues to confront physicians. He believed that such confrontations could not bring positive results but strained nurse/physician relationships, which would ultimately disadvantage nurses.

Establishing a Partnership with Physicians by Interpersonal Interactions

The male nurses had different experiences on how gender influenced their relationships with male or female physicians. Some felt that they had better relationships with male physicians because they could find common interests as men. Others observed that some male physicians liked to work with female nurses. All the male nurses believed that, although there was a power inequality in work, they were equal with physicians outside of the work arena. MMN9, who had worked in the ER for three years, discussed the harmonious nurse/physician relationships in his department.

In our ER, we work and play together with physicians. We play badminton or table tennis. We climb hills together. I don’t think nurses and physicians in other wards get along with each other as well as we do. You know why? The physicians in the ER come from different specialties. But they are ER physicians and work in the ER for a very long time. Even in clinical wards, nurses and physicians do not speak to each other very much. Here we do things together. When they need help, we go over to give them a hand; when we need help, for example, moving beds, they give us a hand. So, we are happy when we work together.

This male’s account implies the nature of teamwork: enough communications among team members. Hierarchy did not disappear but had become more flattened when a harmonious nurse/physician relationship had established. Such harmonious relationships were more often described by the Macanese than the Mainlanders, as one of the males in Macau said that

I observed that physicians in the Mainland enjoy a much higher status than nurses. (MMN3, who had worked for one year in ER)

Discussion

Nurses, patients, and physicians have distinctive features in terms of their roles and status in healthcare systems; thus, each of the three players categorizes itself as a unique and independent group. This study showed that the male nurses managed to establish an inclusive team in which the three players could work harmoniously. According to the SIT, whereas people hold positive attitudes towards ingroup and negative attitudes towards outgroup, the boundary of ingroup is not rigid but contextual.18,19 By working in an inclusive team in a specific clinical environment, nurses, patients and physicians would regard each other as ingroup members and hostility towards each other would reduce. The male nurses were found to be broad-minded to avoid tensions and conflicts with patients and physicians, which was attributed to their masculinities.

Further, perspective-taking, a skill in which one perceives a situation or concept from other people’s point of view, was practiced by the male nurses. Some of them tried to place themselves in patients’ positions and showed their understanding of the latter’s needs. Perspective-taking was the empathy capability and previous studies portrayed empathy as a feminine virtue.31 This study showed that being empathetic can be a masculine feature. Recent studies also revealed patients’ satisfaction with male nurses’ being empathetic.4,5

A subtle phenomenon revealed by the study is the heightened sense of autonomy among patients. The traditional paternalistic model generally had subject patients to healthcare providers’ authority. They were passive players in the healthcare team. Studies found different engagements of patients in decision making concerning their care plans, with the older patients more relying on healthcare providers’ decision-making.32,33 Nowadays, patients are becoming more knowledgeable due to increased access to various sources of healthcare. They have displayed different role traits from previous images of patients.34 The reshaped identity of patients has, in turn, created different intergroup dynamics between patients and healthcare providers.

An essential finding of the study is the demanding style of male nurses in dealing with conflicts with patients. Feminine features have been symbols of nursing professionals, such as humble and gentle.35,36 The robust and confident image of male nurses has added other features to nurse identity. However, the increased distinctiveness with nurse identity did not change the stereotype of nurse/physician power inequality. Male nurses were unwilling to challenge physicians’ dominance, fearing a detrimental effect on nurse/physician relationships. This is in line with a study with Japanese male nurses, which reported that Japanese male nurses were unwilling to challenge physicians’ dominance and chose to stay in the status quo of being subordinate to physicians.37 The males in our study regarded non-confrontation as a way to maintain harmony in the healthcare team, which would ultimately benefit the achievement of the team’s goals. Future research needs to explore whether male nurses from the regions influenced by the Confucius ideology, which advocates social harmony, are less active in confronting hierarchical systems than their counterparts in other regions.

A closer nurse/physician intergroup relationship was observed in Macau than in Mainland China, manifested by frequent interpersonal interactions between nurses and physicians outside professional roles. The male nurses in Macau held a positive attitude towards interpersonal interactions regarding such interactions outside the clinical environment as being beneficial to nurse/physician harmony in healthcare. On the other hand, scholars have doubted the status change via interpersonal interactions because the stereotype of the hierarchy is the system of a system of group relationships that entrench the group conflicts.21 It is suggested that status change can only be achieved by a cultural change made by the collective efforts of the lower status groups.38 However, this study found that nurse/physician interpersonal interactions did transcend the boundaries of outgroups to a certain extent and helped create inclusive groups.

The Implication for Nursing Practice and Education

By including patients into a healthcare team, nurses may judge their patients from an ingroup perspective, meaning they hold a positive attitude towards their patients. There have been several “Expert patient Programs” run by NHS (National Health Service) in the past years, in which patients join medical teams to make treatment plans or act as advisors to develop policies. These practices have induced a changing culture where patients are regarded as the experts of their own health management.39 The nurses can do in the same way. Inclusive symbolic language such as “we” “us” can be used by nurses in establishing therapeutic relationships with patients.

Interestingly, the nurses in this study overtly talked about the importance of partnering with patients, but they rarely described the partnering practices. Studies have called on real actions taken by healthcare providers to work with patients, not just chanting slogans.40,41 Further, this study revealed the gender- and profession-based advantages of male nurses in working with patients. Male nurses need to make appropriate use of the nurse/patient power inequality and avoid a paternalistic style of care model.

There is wishful thinking that jointed education for nursing and medical students would develop ingroup feelings and results in positive attitudes towards each other.21 In China and many other parts of the world, nursing students have been in shared classes with medical students in the past decades. However, the decades’ practices have not narrowed nurse/physician status inequality. Furthermore, studies on jointed classes of medical and dental students reported a widened gap between the two student groups.42 Artificial equality of different professions on campus cannot be immune from the inequality in the real world.21

Other structural and contextual factors, such as salary levels, professional image related to entry requirements, management of health system, teamwork patterns, etc., also influence the professional status of nurses, as reflected in a more harmonious nurse/physician relationship in Macau than in the Mainland. Although the structural and contextual factors cannot fundamentally change the low status of nursing in the hierarchal healthcare system, properly addressing these factors can improve nurses’ group identification and ingroup favoritism. Fundamental changes to the subordinate status of nursing to medical science can only happen with the collective efforts of nurses to enhance the nursing profession’s distinctiveness. The clear boundary of nursing responsibilities should be established, and autonomy of nursing is built independently from medicine so that nurses’ full potentials can be fulfilled, as stated by the males in the study.

Limitations

As qualitative research, this study has the inherited limited generalization of the findings, due to the small sample size of the participants.43 The findings can only reflect the experience of the participants. If the participants had come from different places and health institutes, the outcomes might have been different. Research has revealed Chinese men’s tendency to save face and protect group identity.44 The male nurses might have emphasized or even exacerbated their power and authority but concealed experiences of powerlessness and weakness in dealing with conflicts and tensions with other healthcare team players.

Conclusion

Tension and conflicts between nurses and patients rise now and then. However, few studies have discussed nurse/patient interactions from the intergroup perspective. Gender and professional advantages have shaped nurse/patient interactions. A status quo of the physician/nurse hierarchy is revealed, despite a subtle different degree of the hierarchy between Macau and Mainland China. Nurses, particularly male nurses, have control over nurse/patient relationships. They should make efforts to form more inclusive groups to work with patients. While nurses in different social-economic settings can learn how to overcome the structural and contextual barriers to status inequality among different groups, they should work together to change the fundamental contributors to the hierarchical systems. With male nurses as a critical component of the collective efforts, nurses should strive for the enhanced status of nursing with their colleagues. Their efforts in establishing and engaging in an inclusive healthcare team can not only enhance the distinctiveness of nursing identification but also help to achieve the goals of the team: the patients’ wellbeing and the reduced tensions and conflicts among patients, nurses, and physicians.

Abbreviations

SIT, Social Identity Theory; ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit; HU, hemodialysis unit; OR, operation room; MMN, Macau male nurse; CMN, Mainland China male nurse.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first author and/or the corresponding author based on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The research team in Macau gained ethics approval from the Research Committee of Kiang Wu Nursing College of Macau (Reference no: 2016JAN01); the research team in the Mainland gained approval from the Nursing College, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (https://sedrcihe.cwnu.edu.cn/info/1077/1898.htm, reference no: CJF19019). Confidentiality for personal information was assured. A written consent form was obtained from each participant before interviewing. The Participant informed consent included publication of anonymized responses.

Author Contributions

AM and JW conceived and designed the project. AM and YZ collected data. AM and JW wrote the manuscript draft. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The Macau part of the study is funded by Foundation of Macau (No:1962/DSDSC/2016).

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests for this work. While the funding body provided financial support, it had no role in the design of the study, data collection, data analysis, and writing the manuscript.

References

1. Fernández-Ballesteros R, Sánchez-Izquierdo M, Olmos R, Huici C, Ribera Casado JM, Cruz Jentoft A. Paternalism vs. autonomy: are they alternative types of formal care? Front Psychol. 2019;10:1460. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01460

2. Yi M, Keogh B. What motivates men to choose nursing as a profession? A systematic review of qualitative studies. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52(1):95–105. doi:10.1080/10376178.2016.1192952

3. Sánchez-Izquierdo M, Santacreu M, Olmos R, Fernández-Ballesteros R. A training intervention to reduce paternalistic care and promote autonomy: a preliminary study. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1515–1525. doi:10.2147/CIA.S213644

4. Younas A, Sundus A. Experiences of and satisfaction with care provided by male nurses: A convergent mixed-method study of patients in medical surgical units. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(11):2640–2653. doi:10.1111/jan.13785

5. Budu HI, Abalo EM, Bam VB, et al. “I prefer a male nurse to a female nurse”: patients’ preference for, and satisfaction with nursing care provided by male nurses at the Komfo Anokye teaching hospital. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:47. doi:10.1186/s12912-019-0369-4

6. Vatandost S, Oshvandi K, Ahmadi F, Cheraghi F. The challenges of male nurses in the care of female patients in Iran. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;67(2):199–207. doi:10.1111/inr.12582

7. Saleh MYN, Al-Amer R, Al Ashram SR, Dawani H, Randall S. Exploring the lived experience of Jordanian male nurses: a phenomenological study. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(3):313–323. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2019.10.007

8. Suhariyanto HRTS, Ungsianik T. Improving the interpersonal competences of head nurses through Peplau’s theoretical active learning approach. Enferm Clin. 2018;28(Suppl 1):149–153. doi:10.1016/S1130-8621(18)30056-1

9. Deane WH, Fain JA. Incorporating Peplau’s theory of interpersonal relations to promote holistic communication between older adults and nursing students. J Holist Nurs. 2016;34(1):

10. Hagerty TA, Samuels W, Norcini-Pala A, Gigliotti E. Peplau’s theory of interpersonal relations: an alternate factor structure for patient experience data? Nurs Sci Q. 2017;30(2):160–167. doi:10.1177/0894318417693286

11. Amoah VMK, Anokye R, Boakye DS, et al. A qualitative assessment of perceived barriers to effective therapeutic communication among nurses and patients. BMC Nurs. 2019;18(1):4.

12. Giménez-Espert M, Prado-Gascó VJ. The role of empathy and emotional intelligence in nurses’ communication attitudes using regression models and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis models. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(13–14):2661–2672. doi:10.1111/jocn.14325

13. Setoodegan E, Gholamzadeh S, Rakhshan M, Peiravi H. Nurses’ lived experiences of professional autonomy in Iran. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6(3):315–321. doi:10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.05.002

14. Yarbrough J, Davis L. Bullying behavior does not support the normal standard of care. Manag Healthcare Nurs J. 2019;2(1):1–15. doi:10.18875/2639-7293.2.101

15. Weiss M, Kolbe M, Grote G, Spahn DR, Grande B. Why didn’t you say something? Effects of after-event reviews on voice behaviour and hierarchy beliefs in multi-professional action teams. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2017;26(1):66–80. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2016.1208652

16. Halman M, Baker L, Ng S. Using critical consciousness to inform health professions education. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(1):12–20. doi:10.1007/s40037-016-0324-y

17. Punshon G, Maclaine K, Trevatt P, Radford M, Shanley O, Leary A. Nursing pay by gender distribution in the UK - does the Glass Escalator still exist? Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;93:21–29. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.008

18. Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: JJ T, Sidanius J, editors. Key Readings in Social Psychology. Political Psychology: Key Readings. East Sussex, England: Psychology Press; 2004:276–293.

19. Brown R. The social identity approach: appraising the Tajfellian legacy. Br J Soc Psychol. 2020;59(1):5–25. doi:10.1111/bjso.12349

20. Dirth TP, Branscombe NR. The social identity approach to disability: bridging disability studies and psychological science. Psychol Bull. 2018;144(12):1300–1324. doi:10.1037/bul0000156

21. Kreindler SA, Dowd DA, Dana Star N, Gottschalk T. Silos and social identity: the social identity approach as a framework for understanding and overcoming divisions in health care. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):347–374. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00666.x

22. Willetts G, Clarke D. Constructing nurses’ professional identity through social identity theory. Int J Nurs Pract. 2014;20(2):164–169. doi:10.1111/ijn.12108

23. Statistics and Census Centre of Macau. Gross Domestic Product per capita in Macau. 2020. Available from: https://www.dsec.gov.mo/ts/#!/step2/PredefinedReport/zh-MO/32

24. State Council of People’s Republic of China. China Economy grew by 6.1% in 2019. 2020. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-01/18/content_5470531.htm.

25. Legislative Assembly of Macau. Code of Nurses. 2009. Available from: https://www.al.gov.mo/uploads/attachment/2016-10/908085811bc39edfc2.pdf.

26. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. The national survey on nurses’ salaries-2018. 2019. Available from:https://www.sohu.com/a/339426503_350351.

27. Wang E, Hu H, Mao S, Liu H. Intrinsic motivation and turnover intention among geriatric nurses employed in nursing homes: the roles of job burnout and pay satisfaction. Contemp Nurse. 2019;55(2–3):195–210. doi:10.1080/10376178.2019.1641120

28. Lyu L, Li G, Li J, Li M. Nurse turnover research in China: a bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2015. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;3(2):208–212.

29. Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval American J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. doi:10.1177/1098214005283748

30. Strauss AC, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research:Techniques and Procedure for Developing Grounded Theory. California,CA::Sage,Thousand Oaks; 1998.

31. Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, Koukouli S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(1):26. doi:10.3390/healthcare8010026

32. Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):98. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0779-9

33. Elliott J, McNeil H, Ashbourne J, Huson K, Boscart V, Stolee P. Engaging older adults in health care decision-making: a realist synthesis. Patient. 2016;9(5):383–393. doi:10.1007/s40271-016-0168-x

34. Graham AL, Cobb CO, Cobb NK. The internet, social media, and health decision-making. In: Diefenbach MA, Miller-Halegoua S, Bowen DJ, editors. Handbook of Health Decision Science. New York: Springer New York; 2016:335–355.

35. Dresch V, Sánchez-López M, Saavedra AI. Gender and Health in Spanish Nurses. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto). 2018;28.

36. Kahalon R, Shnabel N, Becker JC. Positive stereotypes, negative outcomes: reminders of the positive components of complementary gender stereotypes impair performance in counter-stereotypical tasks. Br J Soc Psychol. 2018;57(2):482–502. doi:10.1111/bjso.12240

37. Asakura K, Watanabe I. Survival strategies of male nurses in rural areas of Japan. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2011;8(2):194–202. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2011.00176.x

38. Volpato C, Andrighetto L, Baldissarri C. Perceptions of low-status workers and the maintenance of the social class status Quo. J Soc Issues. 2017;73(1):192–210. doi:10.1111/josi.12211

39. Cordier J-F. The expert patient: towards a novel definition. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(4):853–857. doi:10.1183/09031936.00027414

40. Lindsley KA. Improving quality of the informed consent process: developing an easy-to-read, multimodal, patient-centered format in a real-world setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):944–951. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2018.12.022

41. Agha AZ, Werner RM, Keddem S, Huseman TL, Long JA, Shea JA. Improving patient-centered care. Med Care. 2018;56(12):1009–1017. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001007

42. Amin M, Zulla R, Gaudet-Amigo G, Patterson S, Murphy N, Ross S. Dental students’ perceptions of learning value in pbl groups with medical and dental students together versus dental students alone. J Dent Educ. 2017;81(1):65–74. doi:10.1002/j.0022-0337.2017.81.1.tb06248.x

43. Almeida F, Faria D, Queirós A. Strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods. Eur J Educ Stud. 2017;3:369–387.

44. Eriksson T, Mao L, Villeval MC. Saving face and group identity. Exp Econ. 2017;20(3):622–647. doi:10.1007/s10683-016-9502-3

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.