Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Leader Phubbing and Employee Job Performance: The Effect of Need for Social Approval

Received 15 April 2022

Accepted for publication 15 June 2022

Published 23 August 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 2303—2314

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S370409

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Tingting Xu,1 Tingxi Wang,2,3 Jinyun Duan1

1School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China; 2International Business School Suzhou, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China; 3Management School, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom

Correspondence: Jinyun Duan, School of Psychology and Cognitive Science, East China Normal University, 3663 North Zhongshan Road, Shanghai, 200062, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Purpose: A workplace leader’s phubbing (snubbing by using the phone) can create social distance between the leader and employee. We tested whether this social distance might reduce trust, with a negative impact on job performance. The negative impact might be especially strong for employees with a high need for social approval (NFSA).

Methods: Full-time employees (N = 246; 51.63% male, Mage = 35.07, SD = 8.62) in Eastern China completed anonymous questionnaires. The data were collected in three waves with a 2-week interval between each wave. The SPSS macro PROCESS was used to test all research hypotheses.

Results: Regression-based analyses were used to test a moderated serial mediation model. Leader phubbing was associated with employees’ poorer job performance, and this association was mediated by social distance and in turn, low trust. The negative effects of leader phubbing were stronger for employees with a higher NFSA.

Conclusion: This study adds new evidence to the literature on phubbing by showing that employees’ perceptions of leader phubbing might hinder employee job performance. Furthermore, the boundary condition of employee NFSA was emphasized and further expanded the literature in this field. This research provides insights into how the negative impact of leader phubbing on employee job performance can be prevented or reduced.

Keywords: leader phubbing, social distance, trust, job performance, need for social approval

Introduction

When a workplace leader seems distracted by using their smartphone during face-to-face interactions, the employee might interpret the behavior as phubbing—a word that has been coined to represent the combination of “phone” and “snubbing”. According to the 2022 CNNIC report, smartphones have become the most commonly used device for accessing the Internet in China, and 99.7% of cyber citizens in China were smartphone users.1 While providing numerous conveniences for users, smartphone use may also cause more phubbing in offline social interactions, including in the workplace. Related also studies have shown that most participants stated being phubbed by others at recent social activities,2 and 28% of employees reported that using smartphones may be harmful to the relationship between superiors and subordinates.3 In fact, more and more employees experience the use and existence of smartphones in their work, and phubbing also has become a common phenomenon in the workplace.4,5 There are frequent offline interactions within employee-employee dyads and leader-employee dyads, and it may often be observed the case that one employee interrupts face-to-face communication due to excessive viewing of smartphones for some reasons, resulting in another employee feeling being phubbing.

Leader phubbing, employee’s perception that leaders are distracted by using their smartphones during face-to-face talking with their leader, is a new-born negative leader behavior accompanied by the widespread use of smartphones in the workplace.4,6 A limited number of existing studies also have shown that leader phubbing in the workplace is not only common, but also may have a detrimental impact on the organization.4,7 Several studies have documented an association between leader phubbing and employees’ negative work outcomes, such as lower employee self-esteem, phubbing behavior, lower job engagement, and poor job performance.4–8 Meanwhile, few studies to date have examined the internal mechanisms that might explain these associations between leader phubbing and employees’ negative work outcomes. Understanding these mechanisms can be helpful for employees, supervisors, and organizations in preventing or reducing phubbing in the workplace. Based on these, it is necessary to explore further the impact of leader phubbing and the internal mechanism in the workplace.

Our paper tackled the effects of leader phubbing on employees’ job performance and elucidated the psychological mechanism to bridge these gaps. In the current study, we used the perspective of social distance9 as a framework for studying the mechanisms by which leader phubbing is associated with employees’ work outcomes. Our assumption is that leader phubbing increases employees’ sense of social distance, with downstream consequences for worker performance.

The social distance between employees and leaders appears to play a role in the effects of leader behavior on employees’ motivation, leader–employee interaction relationships, and team performance.10–13 Employees’ perception of social distance between themselves and the leader has been shown to be associated with lower leader–follower flexible interactions.11 Employees may perceive greater social distance when there is leader phubbing; they may think that leaders are not interested in them and that they do not deserve the leaders’ attention. We assume that increased social distance may lead to a series of downstream consequences, namely a deterioration of employees’ trust in their leader, and consequent lower job performance. Thus, in the present study, we explored two mechanisms by which leader phubbing is associated with lower employee job performance. Specifically, we tested whether employees’ perceived social distance from the leader and lower trust serially mediate the influence of leader phubbing on poorer employee job performance.

However, not all employees endow the same meaning to social distance from their leader. In particular, an employee’s behavior may depend on their NFSA. Employees with a high NFSA may be guided by others’ opinions as a way to secure relevant others’ approval.14,15 If the employee lacks confidence to act independently, they may react more negatively to high social distance.15,16 Thus, we tested NFSA as a boundary condition of the process by which leader phubbing is associated with poorer employee job performance.

In light of these findings, we developed and tested a moderated serial mediation model (shown in Figure 1) to examine how and when leader phubbing influences employee job performance. The model was tested based on employee questionnaire data collected at three time points, two weeks apart. Such an in-depth exploration of this topic can provide a conceptual foundation for further research and practice, as well as practical guidance for organizations and managers.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical model. Abbreviations: T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; T3, Time 3. |

Theoretical Development and Hypotheses

Leader Phubbing and Employee Job Performance

Leader phubbing, as a form of negative behavior at work, may be related to employees’ less positive work behavior. This negative behavior of leaders reduces the eye contact in the leader-employee interaction, and also may make employees feel unsupported emotionally at work.4,17,18 Therefore, employees may feel excluded when they interact with a leader who is focusing their attention on their smartphones instead of the employees.7 This experience of exclusion, as a negative event experienced by employees in the workplace, will lead to employees’ negative emotions, and then induce employees’ negative work results. Related studies have also shown that leader phubbing can weaken the emotional connection, and induce employees’ negative emotions and work outcomes.5–8,19,20

Moreover, this experience of exclusion can not only make employees feel ignored, but it can send the information to employees that they are not valued in organization.8,18 This may make the employees who have experienced the leader phubbing feel the stress and emotional exhaustion, thus Inhibiting their work engagement and affecting their job performance.8,21 Previous research has also shown that leader phubbing can have a negative impact on employees’ work outcomes, such as employee engagement, job satisfaction and performance.4,5,8 Based on this information, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Leader phubbing is negatively associated with employee job performance.

The Mediating Role of Social Distance

Social distance refers to a subjective perception or experience of the distance with or between others.9 The perception of social distance is considered an important determinant in social interactions. For example, people generally want to have their conversation partner’s undivided attention in face-to-face conversations.4,5,22 Phubbing thwarts this goal and has been shown to negatively impact social interaction quality.23 The perception that the conversation partner is phubbing may in turn increase the sense of social distance. Support for this possibility was provided by an experiment in which participants who had a conversation in the presence of a smartphone (even when no one was using it) reported less closeness with their partner compared to participants who had a conversation without a smartphone present.24

Employees likely have the same desire for undivided attention during interpersonal interactions in the workplace. In face-to-face leader-employee interaction, leader phubbing makes employees feel alienated because phubbed employees are likely to perceive leaders as uninterested in them or themselves as unworthy of leaders’ attention. The distancing cues conveyed by leader phubbing will impair employees’ perceived interpersonal connection within the interaction,9 potentially increasing employees’ perceived social distance from the leader.

The greater the social distance between employees and their leaders, the greater the restrictions on employees’ work interaction.9,11 Moreover, compared to employees who believe that leaders are close by, those who believe their leaders are far away feel more uneasy about the leaders, have stronger perceptions of leader-employee conflict, and believe that the leaders are less familiar with their work.11 The distance between employees and their leader is also a significant predictor of many aspects of the work performance (eg, motivation, leader–follower interactions relationship and team performance).10–13 Based on the above arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ perceived social distance from the leader mediates the relationship between the leader phubbing and the employee’s job performance. Specifically, leader phubbing increases employees’ perceived social distance from the leader, leading to poorer job performance.

The Mediating Role of Trust

Trust in leader defined as employees believe that leaders will not harm their own interests, are more willing to expose themselves without fear of being exploited, and show their weaknesses to the leader.25 Leader phubbing may reduce employees’ trust in several ways. It reduces eye contact with employees, thus undermining their emotional connection.19 Moreover, when employees experience leader phubbing, they may feel that the leaders are multicommunicating interactions with each other, and may think that the leaders do not respect them.4,26 These experiences may undermine employees’ trust in leaders, because to satisfy both sides of an interactive relationship between leader and employee, both sides must concentrate rather than just be physically present.5

Moreover, employees’ work attitudes and behavior may be affected by trust in leaders. Trust can not only increase employees’ positive work attitude (eg, organizational commitment, psychological well-being and job satisfaction), but also increase employees’ positive work results (eg, job engagement) related to work performance.4,27,28 Relevant research also shows that employees’ trust in their leaders is associated with their work-related outcomes (eg, performance).29 Conversely, the lack of trust in leaders can result in poor employee job performance.30 Based on the above arguments, we propose:

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ trust in the leader mediates the relationship between leader phubbing and employees’ job performance, such that leader phubbing reduces the employees’ trust in their leader, leading to reduced job performance.

The Serial Mediating Roles of Social Distance and Trust

In the process of interaction between leaders and employees, the phubbing of leaders pulls them away from face-to-face interaction with employees,31 which makes employees feel neglected and enhances the social distance with leader. High social distance may inhibit social interactions and lead to unpleasant interactions.5,32 Unpleasant interactions can in turn impair trust.30 The formation of trust between leaders and employees depends on the positive close relationships established by pleasant interpersonal interaction, and employees also have the basic need to establish a closer relationship with leaders.31,33

In addition, the high social distance between leaders and employees may also make employees feel that leaders are not interested in themselves,31 destroy the quality of interaction and emotional connection between employees and leaders,19 and reduce employees’ trust in their leader. Thus, we assert that high social distance caused by leader phubbing could undermine employees’ trust in their leaders. Namely, leaders who use smartphones frequently during interactions with employees will intensify the social distance between leaders and employees and further undermine employees’ trust in their leader.

Hypothesis 4: Employees’ perceived social distance from the leader is negatively associated with trust in their leader.

With the decline of employees’ trust in leaders, it may further lead to employees’ negative work performance. The trust in leaders can not only improve employees’ work willingness and work engagement, but also make them more focused on their work tasks,4,34 so as to enhance employees’ work performance. Previous studies have shown that employees’ trust in leaders is a predictor of positive work outcomes such as employees’ high level of work job satisfaction, work engagement and performance.5,8

Leader phubbing may suggest that they are not wholly focused on employees and lack motivation to affiliate with them. Consistent with social distance theory, individuals’ awareness of others’ lack of motivation to affiliate with them may increase their sense of social distance.9 We assert that the increase in social distance caused by experiencing leader phubbing may lead to a lower trust, in turn undermining employee job performance. Based on the above arguments, we further propose:

Hypothesis 5: Social distance and a lack of trust in the leader together mediate the relationship between leader phubbing and employee job performance. Specifically, leader phubbing reduces job performance by increasing employees’ perceived social distance and, thus, reducing trust in their leader.

The Moderating Role of Need for Social Approval

The need for social approval (NFSA) refers to employees’ desire to be recognized and favored by relevant others in the workplace.34 Individuals with a high NFSA lack confidence and depend more upon others’ opinions, and they will act in ways that they think will ensure the approval of others concerned.14,35 In contrast, individuals with low NFSA are less concerned with gaining approval from others, and their attitudes and behaviors are less influenced by others’ opinions.16 We integrated employee NFSA as a moderator of the relationship between social distance and trust into our model. Employees with a higher NFSA may have a stronger negative reaction towards social distance with leaders.

With formal structural power from the organization, the leader is powerful and vital for employees’ career success.36 Employees with high NFSA may exert significant time and energy trying to minimize their social distance from their leaders, and they are more likely to actively seek positive evaluations from their leaders than employees with low level NFSA.14,34 In addition, compared to employees with low NFSA, those with high NFSA may rely more on their leaders’ attitude and behavior as cues for how to ensure approval.36 Employees with high NSFA are more likely than others to perceive high social distance as indicative of leaders’ disapproval, rejection, and distrust, and these perceptions decrease their own sense of trust in the leader.5,30,32 However, compared to employees with high NFSA, those with low NFSA may pay less attention to social distance or regard it as understandable and acceptable, so they are less likely to be affected. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: NFSA moderates the negative relationship between employees’ perceived social distance and trust in their leaders, such that the negative relationship is stronger for employees with a higher NFSA.

Finally, combined with Hypothesis 5 and Hypothesis 6, we argue that the moderating effect of NFSA on the relationship between social distance and trust may also have implications for employees’ subsequent job performance. If Hypothesis 5 was supported, this suggests that leader phubbing influences employees’ job performance indirectly through employees’ perceived social distance and trust in their leader. Meanwhile, combined with Hypothesis 6, we further hypothesize that this indirect effect will vary depending on the individual’s NFSA. Therefore, we further hypothesize that the whole influencing process of leader phubbing on employee job performance will vary based on employee NFSA as follows:

Hypothesis 7: NFSA moderates the serially mediated relationship between leader phubbing and employee job performance through social distance and trust, such that the negative relationship is stronger for employees with a high level of NFSA.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

We invited full-time employees from multiple companies (mainly in the technology, manufacturing and service sectors) located in the Yangtze River Delta area of China (eg, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Nanjing, and Suzhou). Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that the survey was anonymous. We delivered and collected paper surveys to employees and their direct leaders at three waves, with a 2-week interval between each wave, to minimize common method bias.37 At Time 1, employees rated leader phubbing and reported demographic information. At Time 2, employees rated their perceived social distance and NFSA. At Time 3, employees rated their trust in leaders, and the leaders evaluated employee job performance. To ensure the participants’ confidentiality, each questionnaire used the last four digits of their mobile phone number as the code to complete the responses matching at three time points. Finally, we got a final sample of 246 full-time employees (51.63% male, Mage = 35.07, SD = 8.62).

Measures

The measures were originally developed in English. To assure that the measures in the Chinese and English versions of the survey instrument were equivalent, all items underwent a standard translation followed by a back-translation process.38

Leader Phubbing

We used the nine-item scale developed by Roberts and David to measure leader phubbing.4 A representative item is “My leader glances at his/her cell phone when talking to me.” The scale showed high internal consistency (α=0.92) in the current study.

Social Distance

We used the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale (IOS) developed by Aron et al to measure employees’ perceived social distance.39 It contains a single item in which participants select a picture from seven Venn-like diagrams presenting two circles with varying degrees of overlap; the circles represent themselves and their leaders. The respondent selects the diagram that “best describes” the relationship (choices range from nearly complete overlapping [1] to completely non-overlapping circles [7]).

Trust

We used the four items developed by Podsakoff to measure employees’ trust in their leaders.40 A representative item is “I feel a strong loyalty to my leader.” The scale showed high internal consistency (α=0.87) in the current study.

Job Performance

The leaders completed a five-item scale developed by Williams and Anderson to assess the participant’s job performance.41 A representative item is “Performs tasks that are expected of him/her.” The scale showed high internal consistency (α=0.90) in the current study.

Need for Social Approval

We used the five-item scale developed by Crocker to measure employees’ need for social approval.42 A representative item is “My self-esteem depends on the opinions others hold of me.” The scale showed high internal consistency (α=0.80) in the current study.

Control Variables

We controlled employees’ gender and age to maximize the robustness of the results. Related studies have shown that women are less affected by phubbing than men, and younger persons are more tolerant of phubbing.43,44

Data Analysis

Initially, the 350 paired questionnaires were delivered to participants. Ultimately, we obtained a final sample of 246 employees (response rate=70.29%). Among the final sample, the employees’ average age was 35.07 years old (SD=8.62), and 127 (51.63%) employees were men. A total of 71.95% had received a college degree or above, and the average organization tenure was 6.37 years (SD=6.44). All analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0 and Amos 21.0. The descriptive statistics and correlations among variables were calculated, and the items from each variable were summarized and averaged. Hypothesis testing was conducted with the SPSS macro PROCESS.45 Specifically, we tested the main effect (Hypothesis 1) and mediating effects (Hypotheses 2 and 3) using PROCESS Model 4, and tested the serial mediating effect (Hypotheses 4 and 5) using PROCESS Model 6. Furthermore, we tested the moderating effect (Hypotheses 6 and 7) using PROCESS Model 91. Bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) were constructed by extracting 5000 bootstrap samples. Effects are considered statistically significant when the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Amos 21.0 to verify the discriminant validity of the variables. The four-factor model fit the data well (χ2 (59) = 129.34, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07) and was better than alternative models. According to Harman’s single-factor test, the first factor accounted for 29.89% of the total variance that was extracted after factor analysis, so there was little concern about CMV.37 The constructs’ average variance estimates (AVE) were above 0.50, and the composite reliabilities (CR) on each scale were greater than 0.70, which indicates that the convergent validity was adequate.46 The descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and zero-order correlations of the variables are shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations (N = 246) |

Hypothesis Testing

Leader phubbing was negatively related to employee job performance (B = −0.19, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1.

Leader phubbing was also positively related to social distance (B = 0.47, p < 0.001), and social distance was negatively correlated with employee job performance (B = −0.09, p < 0.01). Furthermore, the indirect effect of leader phubbing on employee job performance (indirect effect = −0.04, 95% CI = [−0.079, −0.014]) via social distance was significant, in support of Hypothesis 2. Leader phubbing was negatively related to trust (B = −0.28, p < 0.001) and trust was positively correlated with employee job performance (B = 0.36, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the indirect effect of leader phubbing on employee job performance (indirect effect = −0.10, 95% CI = [−0.163, −0.052]) via trust was significant, supporting Hypothesis 3.

The serial mediating effect results further showed that all pathway coefficients were significant (see Table 2 and Figure 2). More specifically, social distance was negatively related to trust (B = −0.07, p < 0.05), in support of Hypothesis 4. The sequential pathway “leader phubbing→social distance→trust→job performance” was significant (indirect effect = −0.01, 95% CI = [−0.025, −0.002]), supporting Hypothesis 5.

|

Table 2 Results of Regression-Based Tests of the Serial Mediation Model in Predicting Job Performance (N = 246) |

|

Figure 2 Unstandardized path coefficients for the serial mediation model. Note: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. |

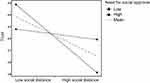

The interaction between social distance and NFSA was significant for trust (B = −0.11, p < 0.05). Figure 3 illustrates the results of simple slope tests. There was a significant and negative relationship between social distance and trust for the high NFSA group (B =−0.15, p<0.001; one SD above the mean) but a nonsignificant relationship for the low NFSA group (B = 0.02, p > 0.05; one SD below the mean). Therefore, Hypothesis 6 was supported. There was also a significant index of moderated mediation (index = −0.02, 95% CI = [−0.040, −0.001]) for the serial indirect effect. The serial indirect effect was significant when NFSA was high (effect =−0.02, 95% CI = [−0.039, −0.006]) but not significant when it was low (effect = 0.01, 95% CI = [−0.014, 0.017]). Hypothesis 7 was thus supported. Table 3 shows the results of tests of the full serial moderated mediation model.

|

Table 3 Results of Regression-Based Tests of the Full Serial Moderated Mediation Model (N = 246) |

|

Figure 3 The moderating effect of employee need for social approval. |

Discussion

The present study developed and tested a moderated serial mediation model based on social distance perspective to test whether and how leader phubbing negatively influences employee job performance. Firstly, our research demonstrated that when experienced by the leader phubbing, employees may produce poor job performance, which supported the existence of the negative effects of leader phubbing. This is also consistent with previous relevant research results, in which the scholars proved that leader phubbing may lead to employees’ negative work outcomes.5–8 In other words, employees are in all probability to the negative influence of leader phubbing. Such results suggest that we need to pay more attention to the harmfulness of leader phubbing with the widespread use of smartphones.

Secondly, the present results showed that employees’ perceived social distance and trust in the leader mediated the relationship between the leader phubbing and the employee’s job performance, respectively. This means that in the offline interaction between employees and leaders, the leader phubbing enhances the social distance between employees and leaders, makes employees feel alienated, and then reduces employees’ work performance. Meanwhile, leader phubbing also reduces employees’ trust in their leaders, which will have a negative impact on employees’ work attitude and behavior, and then lead to employees’ poor performance. In addition, our results find that social distance and trust serially mediate the relationship between leader phubbing and employees’ job performance. Further indicates a pathway by which leader phubbing increases employees’ perceived social distance and subsequently decreases the amount of trust employees place in their leaders, and ultimately has a negative impact on employees’ performance.

Thirdly, the results of the present study confirmed the moderating effect of NFSA. NFSA moderates the indirect effect of leader phubbing and employees’ job performance through social distance and trust. Compared with employees with low NFSA, employees with a higher NFSA who have experienced leader phubbing will show lower job performance. Employees with a high level of NFSA are more likely to regard high social distance as a symbol of dissatisfaction and disapproval, which will undermine their trust in leaders and have a more negative impact on employees’ job performance.

Theoretical Implications

This research makes several important contributions to the literature on leader phubbing in the workplace. First, our research enriches our knowledge of the negative consequences of leader phubbing by examining that leader phubbing is negatively related to employees’ job performance. Consistent with previous studies, the use of smartphones not only provides many conveniences for the workplace but also leads to an increasing phenomenon of phubbing others or being phubbed by others in workplace interpersonal interaction.4,5,17 With the widespread use of smartphones, there is growing concern about the negative impact of smartphone use in the workplace.23 Leader phubbing is a new type of negative leader behavior that appears and increases with the development of the Internet. Organization managers and practitioners need to be aware of the harmfulness of leader phubbing in the workplace.

Second, this research provides a new social distance perspective on the psychological mechanisms by which leader phubbing affects employee performance. Specifically, we demonstrated that employees’ perceptions of phubbing may be associated with their sense of social distance from their leader, with downstream consequences. We proposed and tested a model in which the association between social distance and job performance was mediated first by social distance, and then by trust. The few studies on leader phubbing have shown its negative impact on employees’ self-esteem, trust, engagement, and performance,4,5,7 however, the internal mechanisms of these associations were still further explored. Leader phubbing contradicts employees’ expectations of undivided attention5 and increases employees’ perceived social distance from their leaders. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing the importance of perceived social distance within workplace interactions, as it predicts many adverse work outcomes.4,11

In particular, in the face-to-face interaction between leaders and employees, the leader phubbing makes employees feel alienated, and the increased sense of distance from leaders inhibits the establishment of trust relationship between them. The establishment of a good trust relationship between leaders and employees requires the development and maintenance of good interpersonal relationships in the workplace.31,33 Employees who perceive their leaders’ behavior as phubbing perceive more social distance from the leader and trust the leader less. These thoughts and feelings ultimately undermine interpersonal relationships and trust in the workplace and may eventually lead to negative work results. Consistent with the results of many previous related studies, trust has a significant impact on employees’ positive work attitudes and behaviors.4,5,8 Focusing on leader phubbing, a newborn leader behavior emerging with the mobile Internet era, the results also provide a conceptual basis for interventions to reduce the impact of mobile technology devices on workplace trust building based on interpersonal interaction.24

Third, our research demonstrated a boundary condition of the mediation processes of interest. Specifically, the mediation processes were stronger for employees who had a strong NFSA. This result suggested that NFSA was a significant aggravating factor in the indirect relationship between leader phubbing and employee job performance.15 Our research helps explain why some employees react more negatively than others to leader phubbing, and it addresses the call for research to identify boundary conditions of leader phubbing.47 The results highlight the importance of paying attention to employees’ individual characteristics (eg, need for social approval) as influences on interpersonal interactions in the workplace, especially the interaction between superiors and subordinates.

Practical Implications

This research also points to several practical implications for organizations and management practitioners. First, our work suggests that managers should be aware of the negative implications of leader phubbing on employees. Organizations might need to consider strategies to minimize the practice of phubbing, or the perception of phubbing, in the workplace. Specifically, our work warns of the detrimental influence of leader phubbing and suggests that leaders act as role models in their use of smartphones. Leaders should stay focused and put their smartphones away to communicate with their employees effectively.5 For organizations, it might be necessary to make policies to minimize the negative impact on leaders’ smartphone use during interactions with employees.

Second, leaders ought to minimize employees’ sense of social distance from them. Our research illustrates a psychological mechanism by which leader phubbing hinders employees’ job performance because the perception of higher social distance reduces employees’ trust in leaders. Managers or organizations should minimize employees’ perception of social distance in workplace interpersonal interactions because it predicts many negative work outcomes, such as poor interpersonal relationships and job performance.4,11 Especially in leader-employee interactions, managers should show their presence and attention to employees rather than focus just on themselves and the tiny screen, ignoring the presence of employees. Additionally, organizations could arrange a series of training for members to improve the quality of interactions to lessen perceived social distance within the organization. For instance, leaders could establish regular and positive communication channels to show their willingness to communicate.

Moreover, leaders should also adopt appropriate behaviors and interventions to enhance employees’ sense of trust in them. Employees’ trust in leaders is an important factor affecting their work attitude and behavior. A good trust relationship can promote employees’ positive work results. On the contrary, the lack or destruction of trust may be more likely to make employees produce more negative work results. Leaders should actively improve their interpersonal communication skills, actively communicate and interact with employees without distraction, enhance the emotional connection with employees, and then improve the quality of interaction. Leaders can also actively encourage employees to express their inner feelings and opinions, appropriately give more support to employees, and create an organizational climate of mutual trust.

Third, our work provides managers with a more complete understanding of the influence of NFSA on social interactions. Our results emphasize the importance of considering employees’ individual characteristics in workplace interpersonal interactions. Organizations and leaders should be aware that employees with high NFSA may react more negatively to leader phubbing. Leaders should give employees with high NFSA extra approval, such as more attention during interactions and appropriate acknowledgement and encouragement.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our research has several limitations. First, most of the variables were self-reported, leading to potential common method biases.37 In the future, we may combine various research methods to verify these results. Second, this study only focused on the moderating effect of employee NFSA. Future investigation of other potential individual cognitive characteristics (eg, relationship orientation and rejection sensitivity) moderators is also merited. Third, since this study was conducted in China, the generalizability might be limited. For example, China has a higher tendency toward collectivism,48 and the generalizability of findings to other cultures may be limited. The relationship-oriented interpersonal communication pattern may make the quality of the superior-subordinate relationship effect more prominent than in individualistic cultures. Therefore, cross-cultural comparative research may be relevant for future research.

Conclusion

This study examined how and when leader phubbing influences employee job performance. Our research reveals the negative influence of leader phubbing, which supported that leader phubbing has a significant negative effect on employees’ job performance. Moreover, social distance and trust mediate the relationship between leader phubbing and employees’ job performance. In particular, social distance and trust serially mediate the relationship between leader phubbing and employees’ job performance. Leader phubbing appears to inhibit employee job performance by enlarging the employee’s sense of social distance from the leader and subsequently impairing trust. Moreover, the negative influencing process of leader phubbing is stronger for employees with higher NFSA because they will react more adversely to perceived high social distance. The results have value for both researchers and practitioners who want to reduce phubbing and the negative effects of phubbing in the workplace.

Ethics Statement

The research followed the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee approved all procedures at East China Normal University (No. HR1-1015-2020). The author declares that he has obtained the informed consent from all participants and assured participants were voluntary in the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). The 49st statistical report on internet development in China. China: Cyberspace Administration of China; 2022. Available from: http://www.cnnic.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/202202/P020220407403488048001.pdf.

2. Ranie L, Zickuhr K. Americans’ Views on Mobile Etiquette. Washington DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/26/americans-views-on-mobile-etiquette/.

3. Farber M. Smartphones are making you slack off at work; 2016. Available from: http://fortune.com/2016/06/09/smartphones-making-you-slack-at-work-survey/.

4. Roberts JA, David ME. Boss phubbing, trust, job satisfaction and employee performance. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;155:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109702

5. Roberts JA, David ME. Put down your phone and listen to me: how boss phubbing undermines the psychological conditions necessary for employee engagement. Comput Human Behav. 2017;75:206–217. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.021

6. Khan MN, Shahzad K, Bartels J. Examining boss phubbing and employee outcomes through the lens of affective events theory. Aslib J Inf Manag. 2021. doi:10.1108/AJIM-07-2021-0198

7. Yasin RM, Bashir S, Abeele MV, Bartels J. Supervisor phubbing phenomenon in organizations: determinants and impacts. Int J Bus Commun. 2020;232948842090712. doi:10.1177/2329488420907120

8. Yousaf S, Rasheed MI, Kaur P, Islam N, Dhir A. The dark side of phubbing in the workplace: investigating the role of intrinsic motivation and the use of enterprise social media (ESM) in a cross-cultural setting. J Bus Res. 2022;143:81–93. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.043

9. Magee JC, Smith PK. The social distance theory of power. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2013;17(2):158–186. doi:10.1177/1088868312472732

10. Berson Y, Halevy N, Shamir B, Erez M. Leading from different psychological distances: a construal-level perspective on vision communication, goal setting, and follower motivation. Leadersh Q. 2015;26(2):143–155. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.07.011

11. Du Y, Xu L, Xi YM, Ge J. Chinese leader-follower flexible interactions at varying leader distances: an exploration of the effects of followers in school cases. Chin Manag Stud. 2019;13(1):191–213. doi:10.1108/CMS-03-2018-0461

12. Shamir B. Social distance and charisma: theoretical notes and an exploratory study. Leadersh Q. 1995;6(1):19–47. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90003-9

13. Joshi A, Lazarova MB, Liao H. Getting everyone on board: the role of inspirational leadership in geographically dispersed teams. Organ Sci. 2009;20(1):240–252. doi:10.1287/Orsc.1080.0383

14. Huang CY, Lin CP. Enhancing performance of contract workers in the technology industry: mediation of proactive commitment and moderation of need for social approval and work experience. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2016;112:320–328. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.025

15. Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J Consult Psychol. 1960;24(4):349–354. doi:10.1037/h0047358

16. Sosik JJ, Dinger SL. Relationships between leadership style and vision content: the moderating role of need for social approval, self-monitoring, and need for social power. Leadersh Q. 2007;18(2):134–153. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.01.004

17. Koçak ÖE. Being phubbed in the workplace: a new scale and implications for daily work engagement. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(12):6212–6226. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01635-5

18. Roberts JA, David ME. My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Comput Human Behav. 2016;54:134–141. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.058

19. Nakamura T. The action of looking at a mobile phone display as nonverbal behavior/communication: a theoretical perspective. Comput Human Behav. 2015;43:68–75. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.042

20. Nakamura T, Acar A, Ng M. Cultural comparison for the action of looking at a mobile phone display focusing on independent/interdependent self. Bioceram Dev Appl. 2016;6(2):1–9. doi:10.4172/2090-5025.1000095

21. Harms P, Credé M, Tynan M, Leon M, Jeung W. Leadership and stress: a meta-analytic review. Leadersh Q. 2017;28(1):178–194. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.10.006

22. Burgoon JK, Hale JL. Validation and measurement of the fundamental themes of relational communication. Commun Monogr. 1987;54(1):19–41. doi:10.1080/03637758709390214

23. Abeele MMV, Antheunis ML, Schouten AP. The effect of mobile messaging during a conversation on impression formation and interaction quality. Comput Human Behav. 2016;62:562–569. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.005

24. Przybylski AK, Weinstein N. Can you connect with me now? How the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. J Soc Pers Relat. 2013;30(3):237–246. doi:10.1177/0265407512453827

25. Mayer RC, Davis JH. The effect of performance appraisal system on trust for management: a field quasi-experiment. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(1):123–136. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.123

26. Cameron A-F, Webster J. Relational outcomes of multicommunicating: integrating incivility and social exchange perspectives. Organ Sci. 2011;22(3):754–771. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0540

27. Gill H, Boies K, Mcnally FJ, McNally J. Antecedents of trust: establishing a boundary condition for the relation between propensity to trust and intention to trust. J Bus Psychol. 2005;19(3):287–302. doi:10.1007/s10869-004-2229-8

28. Huang N, Qiu S, Yang S, Deng R. Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: mediation of trust and psychological well-being. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2021;14:655–664. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S311856

29. Mulki JP, Caemmerer B, Heggde GS. Leadership style, salesperson’s work effort and job performance: the influence of power distance. J Pers Sell Sales Manag. 2015;35(1):3–22. doi:10.1080/08853134.2014.958157

30. Rau D. The influence of relationship conflict and trust on the transactive memory performance relation in top management teams. Small Group Res. 2005;36(6):746–771. doi:10.1177/1046496405281776

31. Sbarra DA, Briskin JL, Slatcher RB. Smartphones and close relationships: the case for an evolutionary mismatch. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019;14(4):596–618. doi:10.31234/OSF.IO/RQU6F

32. Howell JM, Hall-Merenda KE. The ties that bind: the impact of leader-member exchange, transformational and transactional leadership, and distance on predicting follower performance. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(5):680–694. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.680

33. Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

34. Lin C-P, Hung W-T, Chiu C-K. Being good citizens: understanding a mediating mechanism of organizational commitment and social network ties in OCBs. J Bus Ethics. 2008;81(3):561–578. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9528-8

35. Grams WC, Rogers RW. Power and personality: effects of machiavellianism, need for approval, and motivation on use of influence tactics. J Gen Psychol. 1990;117(1):71–82. doi:10.1080/00221309.1990.9917774

36. Gooty J, Connelly S, Griffith J, Gupta A. Leadership, affect and emotions: a state of the science review. Leadersh Q. 2010;21(6):979–1004. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.005

37. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

38. Brislin RW. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In: Methodology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1980:389–444.

39. Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(4):596–612. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

40. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Moorman RH, Fetter R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh Q. 1990;1(2):107–142. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(90)90009-7

41. Williams LJ, Anderson SE. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J Manage. 1991;17(3):601–617. doi:10.1177/014920639101700305

42. Crocker J, Luhtanen RK, Cooper ML, Bouvrette A. Contingencies of self-worth in college students: theory and measurement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85(5):894–908. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.894

43. Abeele MV. The social consequences of phubbing: A framework and a research agenda. In R. Ling, L. Fortunati, G. Goggin, S. S. Lim, Y, Li (Eds): The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Communication and Society. Oxford University Press; 2020. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190864385.013.11

44. Xie X, Chen W, Zhu X, He D. Parents’ phubbing increases adolescents’ mobile phone addiction: roles of parent-child attachment, deviant peers, and gender. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2019;105:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104426

45. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York (NY): The Guilford Press; 2013. doi:10.1111/jedm.12050

46. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800312

47. Bastardoz N, Vugt MV. The nature of followership: evolutionary analysis and review. Leadersh Q. 2019;30(1):81–95. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.09.004

48. Hofstede GH. Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2001. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00184-5

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.