Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 12

“Real-life” inhaled corticosteroid withdrawal in COPD: a subgroup analysis of DACCORD

Authors Vogelmeier C, Worth H, Buhl R, Criée C, Lossi NS, Mailänder C, Kardos P

Received 24 October 2016

Accepted for publication 10 December 2016

Published 1 February 2017 Volume 2017:12 Pages 487—494

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S125616

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Claus Vogelmeier,1 Heinrich Worth,2 Roland Buhl,3 Carl-Peter Criée,4 Nadine S Lossi,5 Claudia Mailänder,5 Peter Kardos6

1Department of Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University Medical Center Giessen and Marburg, Philipps-University Marburg, Member of the German Center for Lung Research (DZL), Marburg, 2Facharzt Forum Fürth, Fürth, 3Pulmonary Department, Mainz University Hospital, Mainz, 4Department of Sleep and Respiratory Medicine, Evangelical Hospital Göttingen-Weende, Bovenden, 5Clinical Research, Respiratory, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nürnberg, 6Group Practice and Centre for Allergy, Respiratory and Sleep Medicine, Red Cross Maingau Hospital, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Abstract: Many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) receive inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) without a clear indication, and thus, the impact of ICS withdrawal on disease control is of great interest. DACCORD is a prospective, noninterventional 2-year study in the primary and secondary care throughout Germany. A subgroup of patients were taking ICS prior to entry – 1,022 patients continued to receive ICS for 2 years; physicians withdrew ICS on entry in 236 patients. Data from these two subgroups were analyzed to evaluate the impact of ICS withdrawal. Patients aged ≥40 years with COPD, initiating or changing COPD maintenance medication were recruited, excluding patients with asthma. Demographic and disease characteristics, prescribed COPD medication, COPD Assessment Test, exacerbations, and lung function were recorded. There were few differences in baseline characteristics; ICS withdrawn patients had shorter disease duration and better lung function, with 74.2% of ICS withdrawn patients not exacerbating, compared with 70.7% ICS-continued patients. During Year 1, exacerbation rates were 0.414 in the withdrawn group and 0.433 in the continued group. COPD Assessment Test total score improved from baseline in both groups. These data suggest that ICS withdrawal is possible with no increased risk of exacerbations in patients with COPD managed in the primary and secondary care.

Keywords: COPD exacerbations, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations, health-related quality of life, inhaled steroids

Introduction

The use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) should be limited to patients with more severe disease, particularly those with a history of frequent exacerbations – and even then, only together with a bronchodilator (typically a long-acting β2-agonist [LABA]).1–3 Despite this, a large proportion of patients receive ICS without a clear indication.4–6 This is of concern, since although the use of ICS can bring benefits, they increase the risk of adverse events, such as oral thrush, hoarseness, and pneumonia.7 Moreover, recent studies have suggested that combined treatment with a LABA and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) is at least as effective as an ICS/LABA combination8 and can provide a greater reduction in exacerbations in high-risk patients,9 further questioning the role of ICS in the general management of COPD.

For the substantial proportion of COPD patients already receiving ICS without a clear indication, that is, “off label”, it would be useful to know whether ICS can be withdrawn without affecting disease stability. A number of interventional clinical trials have suggested that in appropriately selected patients (ie, without a history of exacerbations), ICS can be withdrawn without placing the patient at increased risk of exacerbation, including the 26-week INSTEAD study.10 Similarly, in the “real-life” OPTIMO study, over a 6-month follow-up, withdrawal of ICS was not associated with any deterioration in lung function, symptoms, or exacerbation rate in a selected group of patients.11 The 12-month WISDOM study recruited patients at high risk of exacerbation (with severe or very severe airflow limitation and a history of at least one exacerbation in the past 12 months).12 After a run-in period during which all patients received ICS/LABA/LAMA therapy, patients were randomized to either continue ICS/LABA/LAMA or have the ICS gradually withdrawn. Although there was a greater fall in lung function in the ICS withdrawn arm, there was no difference between groups in COPD exacerbation rate. However, all of these studies had a protocol-mandated ICS-withdrawal (even OPTIMO, because although the decision on ICS withdrawal was left to the investigator, patients were recruited into one of two arms, and the stated aim of the study was to assess the impact of ICS withdrawal) and recruited selected populations. DACCORD, or Die ambulante Versorgung mit langwirksamen Bronchodilatatoren: COPD-Register in Deutschland (English translation: Outpatient Care with Long-Acting Bronchodilators: COPD Registry in Germany), is a longitudinal, prospective noninterventional study of 2 years of duration, involving ~6,000 patients with COPD from 349 primary and secondary care practices distributed throughout Germany. The overall aim of the study is to generate data on the course of COPD under typical treatment conditions in the community. A subgroup of patients in DACCORD were taking ICS prior to entry, some of whom continued to receive ICS for the 2-year duration of follow-up, whereas in others, the treating physician decided to withdraw ICS on entry to the study (even though this was not a requirement of the protocol). This permitted an evaluation of the long-term effects of withdrawal of ICS in a “real-life” setting with a more prolonged follow-up than previous studies.

Methods

Study design

Full details of the methods have been previously published,13 along with baseline14 and 1-year follow-up data.15 Specific visits are not mandated by the protocol, but, consistent with usual care in Germany, it was anticipated that data would be recorded approximately every 3 months. At the baseline visit, data collected in electronic case report forms included the following: demographic and disease characteristics, prescribed COPD medication, COPD Assessment Test (CAT), exacerbations in the 6 months prior to entry (defined based on the prescription of oral steroids and/or antibiotics or hospitalization), and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). Data on exacerbations and prescribed COPD medication were then collected every 3 months, with CAT and FEV1 data recorded at annual visits.

Participants

The main inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of COPD fulfilling the German COPD Disease Management Program criteria (one of which is that COPD is confirmed by spirometry testing), age ≥40 years, and initiating or changing COPD maintenance medication. Given the noninterventional nature of the study, the decision to initiate or change medication was made by the patients’ physician prior to inclusion in DACCORD. To recruit as broad a population as possible, patients were excluded only if they were in the asthma Disease Management Program or if they were participating in a randomized clinical trial. The study is registered in the European Network of Centers for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (EUPAS4207; http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=6316) and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Erlangen, Nuremberg, Germany. All patients provided written informed consent prior to inclusion.

Objectives

The main objective of the study was the documentation and description of the care of patients with COPD in Germany. For the analyses reported in this manuscript, the aims were to understand the characteristics of patients most likely to have ICS withdrawn and the consequences (in terms of exacerbations and health status) of ICS withdrawal.

Statistical methods

This subgroup analysis was not formally powered. It included all patients who were receiving ICS prior to entering the study, and who either continued to receive ICS for the duration of the 2-year follow-up or had ICS withdrawn on entry to the study (by the treating physician) and did not recommence ICS for the duration of the full 2-year follow-up. Exacerbation rates were estimated using a negative binomial regression model with annualized numbers of exacerbation as dependent variable and no independent variable. For CAT total score, absolute changes from baseline are presented, together with the proportion of patients with clinically relevant (ie, ≥2 units) changes from baseline – either improvement or worsening. The main analyses were performed on the per-protocol population, which includes all patients in the recruited population who attended the 1- and 2-year visits, and at least two of the three intermediate visits each year, and who had no relevant deviations from the observational plan.

Results

Participants

These analyses are based on data from 1,258 patients (Figure 1). Of these, 236 patients had ICS withdrawn by their physicians prior to entering DACCORD and did not receive ICS for the remainder of the study, whereas 1,022 patients continued to receive an ICS for the full 2-year follow-up. A further 107 patients had ICS withdrawn on entry to the study, but then reinitiated ICS during the 2-year follow-up, 92 (86.0%) of whom had commenced ICS by the 1-year visit. To permit strong conclusions to be drawn on these data, patients who received ICS for a full 2 years need to be contrasted with those who did not receive ICS during this period; these “ICS reinitiator” patients are not included in the analyses described here.

| Figure 1 Patient flow through the study. |

There were few differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups, although those recorded in the database as never smokers were slightly more likely to have ICS withdrawn (Table 1). In terms of disease characteristics, patients with ICS withdrawn had a shorter disease duration, and better lung function, but there were no clinically relevant differences in terms of baseline symptoms or health status. The proportion of patients with at least one exacerbation in the 6-month baseline period was slightly higher in the ICS-continued group than in the ICS-withdrawn group, but the difference was small and not statistically significant (Table 1).

Outcomes

Exacerbations

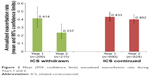

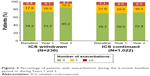

A similar annualized exacerbation rate was observed in the two groups in Year 1, but there was a lower rate in the ICS-withdrawn group than in the ICS-continued group in Year 2 (Figure 2). This was consistent with the percentage of patients with exacerbations, in that the pattern of exacerbations was very similar in the two groups in Year 1, whereas in Year 2, there was a higher proportion of nonexacerbators in the ICS-withdrawn group (Figure 3).

| Figure 2 Mean (95% confidence limit) annualized exacerbation rate during Years 1 and 2. |

| Figure 3 Percentage of patients with exacerbations during the 6-month baseline period or during Years 1 and 2. |

COPD Assessment Test

In the ICS-withdrawn group, there was an improvement from baseline (ie, a decrease) of >2 points in CAT total score at both Year 1 and Year 2; at both time points, the percentage of patients reporting a clinically relevant improvement was >50% (Table 2). In contrast, although there was an improvement in the total score in the group of patients who continued to take ICS, this improvement was <2 units at both visits, and nearly a quarter of patients reported a worsening in CAT total score.

In addition, the proportion of patients were analyzed who had a clinically relevant improvement from baseline at both visits (“sustained improvement”), or a clinically relevant worsening from baseline at both visits (“sustained worsening”). In the ICS-withdrawn group, 116 patients (49.2%) had a sustained improvement and 17 (7.2%) had a sustained worsening. In the ICS-continued group, 345 (33.8%) patients had a sustained improvement and 159 (15.6%) had a sustained worsening. The exacerbation rate was lowest in the patients who had ICS withdrawn and who had a sustained improvement in CAT score (Figure 4). In the ICS-continued group, the rate was lowest in the patients with a sustained improvement in CAT.

COPD maintenance medication use

Prior to entering DACCORD, the majority of patients in the ICS-withdrawn group were receiving ICS plus LABA or LAMA (Figure 5) – most commonly ICS plus LABA (Table 1). In contrast, the ICS-continued group was more likely to be receiving triple inhaled therapy (ICS/LABA/LAMA), with much higher use of theophylline or PDE-4 inhibitors.

At baseline, the majority of patients in the ICS-withdrawn group were receiving LAMA or LABA monotherapy (mainly LAMA); there was limited change over the 2-year follow-up, although the use of combined LABA plus LAMA increased. In contrast, the majority of patients who continued ICS received a triple inhaled therapy regimen throughout the study.

Discussion

There were few differences between groups in terms of baseline demographics or disease characteristics to explain the decision to withdraw ICS. In particular, the two groups had a similar exacerbation history, with a similar (low) percentage of patients having experienced two or more exacerbations in the 6 months prior to entry. The ICS-withdrawn group contained a higher proportion of patients who had been diagnosed for less than a year, and a higher proportion of patients with more preserved lung function (FEV1 ≥80% predicted). However, the biggest difference was in the prior medication: patients were more likely to have ICS withdrawn if they were receiving a single bronchodilator (and generally LABA plus ICS); those on triple ICS/LABA/LAMA therapy were twice as likely to continue to receive ICS. These data suggest (perhaps unsurprisingly) that physicians are more comfortable to withdraw ICS in a population with less severe, less established disease; if the regimen is more established, therapy is more likely to be escalated. What is unexpected is that the level of symptoms and the exacerbation history did not appear to influence this decision.

Following the withdrawal of ICS, the 2-year follow-up data suggest that this group of patients was not at increased risk of exacerbating and was not at increased risk of deterioration in health status. The majority of patients in this arm were receiving ICS plus LABA prior to the study and were then switched to LAMA monotherapy – so did not have an increase in the number of bronchodilators received. In contrast, most patients in the ICS-continued group either were receiving triple ICS/LABA/LAMA therapy prior to the study or had treatment escalated from ICS plus LABA or LAMA to triple therapy (perhaps because the mean time since diagnosis was longer in this group). Because LAMA monotherapy has been shown to be as effective as ICS/LABA in terms of the reduction in exacerbations,16 this could explain why there was no increase in the percentage of patients exacerbating following ICS withdrawal.

The progressive nature of COPD makes looking at changes over time important – especially for end points that evaluate the overall impact of the disease on patients, such as CAT. The overall CAT scores tended to be better in the ICS-withdrawn group – not only at Year 1 but also at Year 2. Furthermore, nearly 50% of patients in the ICS-withdrawn group had a clinically relevant improvement from baseline at both Year 1 and Year 2. The importance of these findings is that few patients in the ICS-withdrawn arm had a clinically relevant decrease in health status, so addressing one of the other concerns over ICS withdrawal. Furthermore, in the ICS-continued group, the exacerbation rate appeared to correlate with CAT total score because it was lower in patients with a sustained improvement in CAT than in those with a sustained worsening. This is consistent with a previous analysis – although using mean CAT total score.17 Because the current analysis was based on the percentage of patients with a clinically relevant change from baseline, this suggests that CAT may be useful as a surrogate predictor of future exacerbation risk at individual patient level, not just using group means.

Studies, such as TORCH, have clearly demonstrated the benefits of ICS in the management of COPD – in terms of not only exacerbations but also health status and lung function, especially in patients with FEV1 <50% predicted.18,19 However, the safety profile of ICS (in particular pneumonia events) means that the risk–benefit profile of ICSs has to be considered before they are initiated.1,20 The introduction of a number of once-daily LAMA/LABA combinations, together with data from studies, such as FLAME, suggesting that these LAMA/LABA combinations are at least as effective as ICS/LABAs, has potentially narrowed the patient population that have a clear benefit from ICSs,8,9 thus altering the risk–benefit balance. Although these data are useful when initiating treatment, for patients already on ICS physicians face the decision of whether ICS can be withdrawn without placing their patient at risk. Lack of clear data, together with a fear that the removal of ICS could trigger exacerbations, has resulted in a gradual “drift” to triple ICS/LABA/LAMA therapy.4–6 A number of interventional trials have evaluated ICS withdrawal in COPD, three of the earliest of which were included in a meta-analysis conducted by Nadeem et al.21 Although these studies recruited patients at high risk of COPD exacerbations, there was no increased risk of exacerbation in the ICS-withdrawal arms of these studies (relative risk: 1.11, 95% confidence interval: 0.84–1.46). In the more recent WISDOM study, which also recruited patients at high risk of exacerbations (based on airflow limitation), the annualized rate of exacerbations was no different in the two groups, with rates of 0.95 in the ICS-withdrawn arm and 0.91 in the ICS-continued arm.12 In INSTEAD, which recruited patients at low risk of exacerbations who had been taking ICS/LABA for at least 3 months prior to entry, the rates were 0.67 in the ICS-continued group and 0.57 in the mono-LABA group – again with no difference between arms (although a numerically lower rate in the mono-LABA group).10 Finally, the “real-life” OPTIMO study also recruited patients at low risk of exacerbations, following them for 6 months – with no difference in exacerbation rates (0.34 and 0.37 exacerbations per patient per 6 months).11 The results of DACCORD are consistent with these previous studies, in that the rates of exacerbations in the two arms during the first year were similar (although the rates in DACCORD were lower in both arms than in these prior studies). However, DACCORD followed the patients for a much longer duration, thus providing additional reassurance beyond the limited follow-up period of these previous studies.

As this was a “real-life” study, and these data are from a subgroup analysis, there are of course a number of caveats over the interpretation of the results. 1) Most importantly, the reason for ICS withdrawal (or continuation) was not captured. 2) In common with most such studies, neither the reason for the initial ICS prescription nor the duration of ICS use was recorded. 3) There is a potential for selection bias because the population included in this analysis had a low rate of exacerbations (the vast majority of patients did not exacerbate in the 6 months prior to entry), and thus were potentially not indicated ICS. However, this subset of patients is similar to the overall DACCORD population, in which 31.2% of patients classified as Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) A and 34.3% as GOLD B (ie, at low risk of exacerbations, and therefore not indicated ICS) were receiving an ICS-containing regimen at baseline.14 This is also consistent with a number of database studies. For example, in an analysis of US data, only 27.1% of patients with COPD who had newly initiated ICS/LABA treatment had an exacerbation history.4 Furthermore, in a UK analysis, more than half of the patients receiving ICS/LABA were classified as GOLD A or B, as were more than a third of patients receiving ICS/LABA/LAMA.6 In another analysis of UK data, 21% of patients in GOLD A and 30% in GOLD B were receiving ICS/LABA/LAMA,5 highlighting the need for information on the effects of ICS withdrawal. DACCORD, by recruiting a representative, “real-life” population, can help to address this need.

In conclusion, these data add to those from recent interventional, randomized clinical trials, in suggesting that ICS withdrawal is possible with no increased risk of exacerbations in patients with COPD who are being managed in standard primary and secondary care settings – especially if they are not currently exacerbating.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the investigators and patients at the investigative sites for their support of this study.

Writing support was provided by David Young of Young Medical Communications and Consulting Ltd. This support included the development of the first draft of the manuscript, under the guidance of the authors, and the coordination of author comments and approval, and was funded by Novartis Pharma GmbH. This study was funded by Novartis Pharma GmbH.

Disclosure

CV reports personal fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie – Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Novartis, and Takeda, and grants and personal fees from Grifols. HW reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Klosterfrau, Menarini, Novartis, and Takeda. RB reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Teva, and grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Roche. C-PC reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Takeda, and Berlin-Chemie. NSL is employed at Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany, the sponsor of the study. CM is employed at Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany, the sponsor of the study. PK reports personal fees from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Menarini, and Takeda. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Available from: www.goldcopd.org. Published 2016. Accessed July 22, 2016. | ||

Glaxo Group Limited. Summary of Product Characteristics: Relvar Ellipta 92 micrograms/22 Micrograms Inhalation Powder, Pre-Dispensed. Brentford, Middlesex, UK; 2013. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2013/20131113127002/anx_127002_en.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2016. | ||

AstraZeneca UK Limited. Summary of Product Characteristics: Symbicort Turbohaler 200/6 Inhalation Powder. Luton, Bedfordshire, UK: AstraZeneca UK Limited; 2015. | ||

Patel J, Mapel DW, Roberts MH, et al. Time to treatment augmentation among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) newly initiated on long-acting muscarinic agents (LAMA) or inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA) combination therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191 suppl:A5774. | ||

Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10(1):2207–2217. | ||

Price D, West D, Brusselle G, et al. Management of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patterns. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:889–905. | ||

Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EHA, Fong KM. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD002991. | ||

Vogelmeier CF, Bateman ED, Pallante J, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily QVA149 compared with twice-daily salmeterol-fluticasone in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ILLUMINATE): a randomised, double-blind, parallel group study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):51–60. | ||

Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2222–2234. | ||

Rossi A, van der Molen T, Del Olmo R, et al. INSTEAD: a randomised switch trial of indacaterol versus salmeterol/fluticasone in moderate COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1548–1556. | ||

Rossi A, Guerriero M, Corrado A; On behalf of the OPTIMO/AIPO Study Group. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids can be safe in COPD patients at low risk of exacerbation: a real-life study on the appropriateness of treatment in moderate COPD patients (OPTIMO). Respir Res. 2014;15:77. | ||

Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1285–1294. | ||

Kardos P, Vogelmeier C, Buhl R, Criée C-P, Worth H. The prospective non-interventional DACCORD Study in the National COPD Registry in Germany: design and methods. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15(1):2. | ||

Worth H, Buhl R, Criée CP, Kardos P, Mailänder C, Vogelmeier C. The “real-life” COPD patient in Germany: the DACCORD study. Respir Med. 2016;111:64–71. | ||

Buhl R, Criée C-P, Kardos P, et al. A year in the life of German patients with COPD: the DACCORD observational study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11(1):1639–1646. | ||

Wedzicha JA, Calverley PMA, Seemungal TA, et al. The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):19–26. | ||

Karloh M, Fleig Mayer A, Maurici R, Pizzichini MMM, Jones PW, Pizzichini E. The COPD assessment test: what do we know so far?: a systematic review and meta-analysis about clinical outcomes prediction and classification of patients into GOLD stages. Chest. 2016;149(2):413–425. | ||

Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al; TORCH investigators. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–789. | ||

Kew KM, Dias S, Cates CJ. Long-acting inhaled therapy (beta-agonists, anticholinergics and steroids) for COPD: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD010844. | ||

Kew KM, Seniukovich A. Inhaled steroids and risk of pneumonia for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD010115. | ||

Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJC, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD – a systematic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.