Back to Journals » Open Access Journal of Contraception » Volume 10

Improving Voluntary, Rights-Based Family Planning: Experience From Nigeria And Uganda

Authors Hardee K , Jurczynska K, Sinai I, Boydell V , Muhwezi DK, Gray K, Wright K

Received 16 May 2019

Accepted for publication 10 October 2019

Published 4 November 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 55—67

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJC.S215945

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Igal Wolman

Karen Hardee,1 Kaja Jurczynska,2 Irit Sinai,3 Victoria Boydell,4 Diana Kabahuma Muhwezi,5 Kate Gray,6 Kelsey Wright7

1What Works Association, Arlington, VA, USA; 2Palladium, London, UK; 3Palladium, Washington, DC, USA; 4Graduate Institute Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; 5Reproductive Health Uganda, Kampala, Uganda; 6IPPF, London, UK; 7University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA

Correspondence: Karen Hardee

What Works Association, Arlington, VA, USA

Email [email protected]

Background: Growing focus on the need for voluntary, rights-based family planning (VRBFP) has drawn attention to the lack of programs that adhere to the range of rights principles. This paper describes two first-of-their-kind interventions in Kaduna State, Nigeria and in Uganda in 2016–2017, accompanied by implementation research based on a conceptual framework that translates internationally agreed rights into family planning programming.

Methods: This paper describes the interventions, and profiles lessons learned about VRBFP implementation from both countries, as well as measured outcomes of VRBFP programming from Nigeria.

Results: The intervention components in both projects were similar. Both programs built provider and supervisor capacity in VRBFP using comparable curricula; developed facility-level action plans and supported action plan implementation; aimed to increase clients’ rights literacy at the facility using posters and handouts; and established or strengthened health committee structures to support VRBFP. Through the interventions, rights literacy increased, and providers were able to see the benefits of taking a VRBFP approach to serving clients. The importance of ensuring a client focus and supporting clients to make their own family planning choices was reinforced. Providers recognized the importance of treating all clients, regardless of age or marital status, for example, with dignity. Privacy and confidentiality were enhanced. Recognition of what violations of rights are and the need to report and address them through strong accountability systems grew. Many lessons were shared across the two countries, including the need for rights literacy; attention to health systems issues; strong and supportive supervision; and the importance of working at multiple levels. Additionally, some unique lessons emanated from each country experience.

Conclusion: The assessed feasibility and benefits of using VRBFP programming and outcome measures in both countries bode well for adoption of this approach in other geographies.

Keywords: rights-based family planning, Nigeria, Kaduna State, Uganda

Introduction

Background

The 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, which articulated an ambitious numeric goal for family planning (FP) use worldwide, increased attention to the need for ensuring that programs designed to reach that aspiration are voluntary and rights-based. Despite the focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights that emanated from the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development,1 including growing attention to human rights and health,2–10 there was little guidance on what a rights-based approach to FP is and how it could be operationalized in programming. Moreover, there was little understanding of how implementing a rights-based approach might be different from a focus on improving quality of care, and how it moves beyond business-as-usual programming. Evidence on the outcomes of rights-based FP programming did not exist. Following the summit, a number of frameworks and guidance documents identified the human rights that relate to FP,11,12 as well as the key elements needed for voluntary, rights-based FP (VRBFP) programming.13–20

As Kumar et al15 wrote,

A rights-based approach to family planning (FP) is one in which all phases of a program (needs assessment, planning, implementation, monitoring, evaluation and management) are viewed through the lens of individuals’ human rights and how rights are, or are not, upheld in communities and in FP programs.

These programs should be designed to fulfil the rights of individuals and couples to determine freely the number and timing of their children, with access to quality information and services, free from discrimination, coercion or violence.3 An outcome of the summit with an explicit rights-based focus is that to ensure those overarching rights, WHO12 and FP202011 identified a number of rights and empowerment principles that FP programs need to address, namely: acceptability; accessibility; availability, quality; accountability; agency, autonomy and empowerment; equity and non-discrimination; informed choice; participation; and privacy and confidentiality (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Definitions Of Rights And Rights Principles |

Some studies have focused on specific rights in programs, most notably quality of care21–23 In undertaking this work, we found no evidence of any programs that had attempted to address all of these rights principles in programming. A review of evidence for VRBFP programming that preceded this work noted that “rights need to be more explicit in studies referring to family planning interventions in order to ensure that rights become embedded in family planning programming”.24

This paper describes two first-of-their-kind interventions and implementation research studies in Kaduna State, Nigeria (hereafter Nigeria) and Uganda that: 1) operationalized a VRBFP approach, including all of the rights principles at service delivery, and; 2) measured the health and rights outcomes of VRBFP approaches at the service delivery level. Similar and/or adapted tools and approaches were used during the implementation and results measurement at the service delivery level in both countries. This paper includes lessons learned from implementation in both countries and VRBFP programming outcomes from Nigeria.

The VRBFP Intervention In Nigeria

Kaduna State is located in the northwest zone of the country, where strong cultural, religious, and gender norms – particularly the dominance of men in society – inhibit the use of family planning.25 Though contraceptive uptake is higher in Kaduna compared to neighboring states, use stagnated at around one-fifth of all married women (all methods) between 2013 and 2017.26,27 Unmet need for FP is high, increasing from approximately 6% in 2013 to 28% in 2017.26,27 Non-use and unmet need for FP are attributed to women’s lack of autonomy to make decisions about reproduction and contraceptive use,28 including real or perceived opposition to uptake by a spouse, family member, or the broader community.29 Service barriers, including the unavailability of desired methods at facility sites, inadequate provider clinical training, and provider attitudes and biases, hinder contraceptive uptake also. Recognizing these realities, the Kaduna State government articulated an ambitious two-year (2016–2018) Birth Spacing Costed Implementation Plan (CIP), intended to guide FP programming across the state.30 The CIP is aligned with Nigeria’s national commitment made at the 2012 Summit and its subsequent Family Planning Blueprint.

Starting in 2016, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Palladium implemented a package of VRBFP interventions across Kaduna State, Nigeria, and evaluated its effects on women’s health and rights outcomes. The interventions, which affected change at policy-, service delivery-, community- and individual-levels, were implemented over a 12-month period. This paper focuses on the service delivery component of the intervention package only. Five service-level interventions were executed in 15 public primary healthcare treatment facilities: building provider and supervisor capacity on FP and the voluntary, rights-based approach; developing facility-level action plans; undertaking mentorship to support implementation of the action plans; establishing or strengthening community structures, or Facility Health Committees (FHCs), to support facility-level activities; and undertaking mentorship of community structures (Table 2). Training and supervision materials on VRBFP were developed for the intervention, and the rights principles listed in Table 1 were simplified into communication materials for clients, including a poster that was prominently displayed in health facilities receiving the intervention (Figure 1).

|

Table 2 Voluntary, Rights-Based Family Planning Interventions At The Service Delivery Level In Kaduna State, Nigeria And Uganda |

|

Figure 1 VRBFP poster developed for clients in Nigeria. Notes: A similar poster was developed for Uganda by Reproductive Health Uganda. (this poster is available at: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/sites/default/files/Know_Your_Rights.pdf). Image courtesy from Family Planning 2020, United Nations Foundation. |

The VRBFP Intervention In Uganda

Demand for FP in Uganda is high, with a contraceptive prevalence rate of 27.3% among all women of reproductive age and 28% unmet need in 2016. This suggests that women and men’s ability to freely decide on the number and spacing of their children is severely undermined.31 This is even more acute for poorer and rural Ugandan women.42 Despite the high need, a range of factors affect the use of FP services in Uganda. People live, on average, 3 to 5 km from the nearest public health facility, or a 40-min walk, the dominant form of transportation/movement.32 Women also encounter inadequate FP commodities, supplies, and equipment, curtailing choice. The facilities are oversubscribed, with congestion and overstretched personnel.33–35 The health personnel who will attend them have limited knowledge and capacity of specific complex methods and have perceived bias on certain contraceptive methods (UMOH 201442). This includes bias against adolescents due to age of consent and requiring spousal permission.33

In 2016, Reproductive Health Uganda (RHU), with support from the International Planned Parenthood Federation’s Support for International Family Planning and Health Organizations 2: Sustainable Networks Project, implemented a project to operationalize the Government’s commitment to VRBFP in four public health facilities in the Northern and Eastern Districts of the country. Rights-based FP was included in the Ugandan Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan for 2015–2020 (UMOH, 201442) and discussed in three national consultations between 2013 and 2015.36 Based on the consultations, the 12-month project aimed to address four issues, namely: increase access to information on voluntary family planning and rights; ensure the implementation of existing (good) policies; increase access to rights-based services, including for youth; and address religious and cultural norms, notably resistance from men, that act as barriers to access to family planning. The project worked at the policy, service delivery and community levels; in this paper, we focus on the service delivery component only. Four service-level interventions were undertaken across 4 public primary healthcare facilities: in-service training for providers on FP and VRBFP; public sector facility systems strengthening through tailored action plans; provider supervision and support; and Health Unit Management Committee (HUMC) orientation and support (Table 2). The project in Uganda adapted the client poster used in Nigeria (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 List of What clients should and should not expect from VRBFP Services, used in both Nigeria and Uganda.Note: Image courtesy from Family Planning 2020, United Nations Foundation. |

Methods

This paper describes the 1) VRBFP implementation process as measured through diverse qualitative approaches in both countries; and 2) outcomes of VRBFP programming in Nigeria only, measured through a common quantitative data collection tool. Because there was no existing way to measure all aspects of VRBFP within service delivery, the two projects collaborated to jointly design a quantitative tool specifically for this purpose.37 The VRBFP Service Delivery Measurement Tool adheres to the globally agreed rights and empowerment principles for FP noted above11,12 and aligns with the service delivery level of the VRBFP Conceptual Framework.18 The implementation research was conducted by Palladium in Nigeria and by the Evidence Project (Population Council and IPPF) in Uganda.

In Nigeria, three sources of information were analyzed to describe the implementation process and identify implications for future VRBFP programming: 1) pre- and post-tests for all provider training events, as well as training of FHC members; 2) more than 200 logbooks capturing insights from ongoing provider mentorship on VRBFP; and 3) focus group discussions with treatment facility health providers. For the evaluation in Nigeria, data were collected from the 15 intervention facilities at baseline and again at endline using the VRBFP Service Delivery Measurement Tool, with minor modifications for context. This quantitative tool comprised four modules: a facility assessment; interviews with facility health providers (baseline n=37, endline n=40); exit interviews with facility clients (baseline n=429, endline n=444); and simulated client visits (baseline and endline n = 60). In addition, service statistics were collected from intervention facilities throughout the intervention period, starting 3 months before implementation began.

In Uganda, a retrospective case study on the implementation process was undertaken to describe the activities and document the perspectives of those involved in operationalizing VRBFP. The case study included 1) a document review, including pre- and post-tests for all provider training events and action plans; 2) key informants interviews with facility-based providers, RHU staff, HUMC members, facility in-charges (health facility managers) and representatives from collaborating human rights organizations (n-16), and; 3) focus group discussions with male champions and community health workers who were trained by the project. A baseline and midline (after 8 months of implementation) were conducted using the VRBFP Service Delivery Measurement Tool in the four intervention sites and three comparison sites. Findings from the baseline in Uganda are reported by Wright et al37 and Hardee38 http://evidenceproject.popcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Hardee-IUSSP-RBFP-Uganda-FINAL-10.31.17-.pdf).

Both protocols received ethical approval and adhered to all international, Nigerian and Ugandan standards for research with human subjects. Ethical approval for Nigeria was obtained from the Kaduna State Health Research and Ethics Committee; for Uganda approval for the study was obtained from the Population Council’s Institutional Review Board and the Makarere University School of Public Health. All respondents consented to participate and signed an informed consent form.

Results

Nigeria

Findings On The Implementation Process

Overall, substantial improvements in provider adherence to VRBFP principles were observed over the 12-month intervention period when triangulating pre- and post-tests associated with training, mentorship logbooks, and focus group discussions. A significant share of providers, supervisors, and FHC members improved their rights literacy, including their ability to identify rights principles, the risks associated with not adopting VRBFP, factors that support rights-oriented services, and more. Moreover, a larger share of facilities became better equipped to provide VRBFP services (“rights-ready”) as captured through mentorship logbooks. Specifically, providers and supervisors addressed many of the systemic barriers to service quality and utilization, including through advocacy to local governments. These included: acquiring needed job aids and information, education, and community materials on FP; securing new equipment for the FP unit; creating and implementing client feedback mechanisms (suggestion boxes and exit interviews); improving the integration of FP and HIV services; and securing greater auditory and visual privacy for counseling and service provision (e.g., purchase and installation of curtains).

Findings from the focus group discussions with providers in the treatment facilities further illustrate the changes promoted by the VRBFP intervention. When reflecting on the intervention, facility providers noted improvements in the quality of their counseling sessions, clients’ experience of free choice, as well as their self-awareness about biases they had related to family planning and who should use it. Related to improvements in the quality of counseling, a nurse/midwife who had been working in her current facility for 4 years explained:

Clients would not speak up before, but now they even tell you deep things about themselves and what their husband wants. For example, I had two clients that talked about their husband wanting to marry more wives because he wanted more children. Counselling them and helping I was able to help them choose a method that they can use and balance the whole situation.

A Community Health Extension Worker, who had moved from the training facility 9 months prior to the focus group discussion described improvements in minimizing bias:

Before this training, there were certain things we do, for example how we decline teenagers and unmarried adults counseling or access to any method because they are not married, or we say she is not old enough to use them. But now we let them in and counsel them and let them make their choice.

A Community Health Extension Worker, who had been working in her current facility for 3 years recognized that there had been improvements in free choice, saying:

Before now, a provider can just choose for a client any method she, the provider, feels like giving the client and she does not have the confidence to challenge the provider or object it. With VRBFP, the posters we put up and constant informing the clients, they now can boldly refuse any method the provider tries to impose on them.

Additionally, some providers noted that privacy and confidentiality were respected more. A Facility In-Charge, who had moved from her facility 7 months prior to the focus group discussion, observed:

[…] Sometimes when a client comes to the facility some of the providers gossip about them and start telling her neighbors or her friends, ‘I saw her in the facility or clinic at the FP stand’. The client needs to have privacy when she is being counselled.

Findings From The Baseline And Endline In Nigeria And Service Statistics

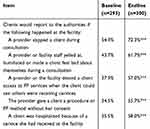

Based on service statistics, the intervention facilities observed an increase in contraceptive uptake during the intervention period, from a mean monthly number of 24 new FP clients per facility per month before the intervention, to 42 in the last quarter. Moreover, statistically significant improvements were observed in treatment sites from baseline to endline across several rights dimensions (Tables 3 and 4), as captured through the VRBFP Service Delivery Level Measurement Tool:

- Decreased provider bias against adolescents, unmarried women, and women who wish to use contraception without their husband’s permission (measured by providers expressing willingness to provide them services);

- Improvements in the quality of provider–client interactions, including an increased share of clients who experienced full informed choice (composed of 5 question categories), free choice, and who rated themselves as being treated respectfully;

- Clients’ confidentiality was increasingly protected, they were more actively engaged in their own care, and providers increasingly sought their opinions about the facility and services;

- Decreased share of clients who were asked to pay for services that were free, like contraceptive commodities;

- Increased share of providers and clients who became more aware of the conditions that constitute rights vulnerabilities or abuses, and what to do if these behaviors occur; increase in those who were also more willing to report violations.

|

Table 3 Provider Perceptions About Rights Violations, Kaduna State, Nigeria |

|

Table 4 Client Perceptions About Rights Violations, Kaduna State, Nigeria |

Key areas for additional progress included bolstering several other dimensions of counseling (e.g., checking for contraindications), safeguarding privacy (e.g., providers who interrupt ongoing FP consultations), and minimizing biases for other populations (e.g., those who are mentally disabled). Moreover, while a significantly larger share of clients knew and understood their rights, this still represented just a small proportion of those receiving services. Additionally, rights dimensions conditional on a well-functioning health system – particularly supportive supervision – continued to lag behind.

Uganda

Findings On The Implementation Process

Substantial improvements in adherence to VRBFP principles were observed when triangulating pre- and post-tests associated with training, and from key informant interviews and focus group discussions conducted as part of a qualitative assessment of the intervention in Uganda. In the pre- and post-tests associated with training, providers and in-charges showed improved knowledge of VRBFP (31% to 91%) and, increased knowledge of rights and empowerment principles (62% to 78%). Service providers and facility in-charges who were interviewed at the end of the intervention indicated that the training was relevant and that it supported their work by improving their capacity to counsel clients and couples, manage side effects, and refer clients for services not available at the facility. Providers noted that they were more aware of the right of clients to choose their contraceptive methods and that they felt more prepared to counsel on a range of methods. They noted paying greater attention to privacy for clients.

The implementation of facility-level action plans resulted in positive improvements. Key informants identified counseling as an area that was working well, as well as an expanded method mix. With other funding, RHU provided additional commodities, equipment and training for long acting and reversible contraceptives, enabling these methods to be offered for the first time in the public facilities and improving the range of choices for clients. In three of the four facilities, providers and in-chargers reorganized the space at the facility to promote privacy and confidentiality. Providers and in-charges noted several areas for further to improvement in order to support VRBFP including, regular supervision, further guidance on client-centered counselling, knowledge of service delivery standards, and referral protocols. These areas for further improvement required actions from higher authorities to operationalized and implement.

The Health Unit Management Committees noted several changes. In one facility, a permanent structure was constructed to expand the health unit (in which family planning is offered), greater attention was given to collecting and responding to client feedback, more men were accompanying their wives for MCH and voluntary family planning services, and there were increased efforts by HUMC to monitor commodity leakage. In another district, HUMC members reported giving family planning greater priority in budget discussions, treating stock-outs as a rights issue, increasing men’s engagement and establishing suggestion boxes. Areas for further improvement, such as the lack of capacity to meet the demand for services with an adequate supply of commodities and other resources, also required higher level authority engagement.

Discussion

The intervention components in both projects were similar in design and in materials. Both programs:

- Built provider and supervisor capacity in VRBFP using curricula adapted from Kumar et al39 and the Respond Project;40

- Developed facility level action plans, and supported action plan implementation

- Aimed to increase clients’ rights literacy at the facility using posters and handouts; and

- Established or strengthened the health committee structures to support VRBFP.

The implementation of these program elements was adapted to the local context and available budget.

The VRBFP interventions in Nigeria, and Uganda, which built on existing programs rather than being something completely new, resulted in beneficial outcomes. Rights literacy increased and providers were able to see the benefits of taking a VRBFP approach to serving clients. The importance of ensuring a client focus and supporting clients to make their own FP choices was reinforced. Providers saw the importance of treating all clients, regardless of age or marital status for example, with dignity. Privacy and confidentiality was enhanced. Recognition of what violations of rights are and the need to report and address through strong a accountability systems them grew.

A number of lessons learned can be drawn from these two experiences with implementation of VRBFP that will be useful to other countries as they design and implement VRBFP programming.

Lessons From Both Countries To Enhance VRBFP Programming

Although intervention components were adapted to their specific context, both the Nigeria and Uganda programs shared similar VRBFP curricula, supervision tools, client information posters, and activities to strengthen local community health structures. Given the parallels in VRBFP programming approach, common lessons can be drawn from both projects. These include the need for rights literacy among all stakeholders; attention to health systems issues; strong and supportive supervision; and the need to work at multiple levels. Country-specific lessons can also be drawn.

The Need For Rights Literacy

Rights literacy was low among all stakeholders in both countries at the beginning of the projects. Through training on rights literacy, providers underwent a mind shift, with many ‘aha’ moments about what they had considered “normal” before. For example, situations or actions such as turning youth away, lack of accurate or full information for clients, limited method options due to stock-outs, or poor-quality services – have now been successfully elevated to the level of rights issues.

Targeted training on rights principles as part of an existing curriculum embedded in provider pre- and in-service trainings can effectively generate attitudinal and behavioral change. The concept of rights-based FP resonated with service providers and prompted changes in counselling practice and in clients overall experience when attending a facility, including privacy. Training on rights does not need to be done separately from other training; in fact, integrating it into existing training reinforces that rights are not divisible from their clinical practice.

Attention To Health Systems Issues

To successfully operationalize VRBFP, basic health systems standards need to be in place. This was a major challenge in public facilities whose service providers appreciated rights principles but faced structural challenges in making their services “rights-ready” and these challenges were often beyond their control.

A weak health system limits the extent to which rights can be realized within facilities. In Nigeria, inadequate funding for outreach services, supervision, FP equipment and consumables, and provider salaries, negatively affected the quality, availability, and accessibility of services, as well as full participation by clients and accountability of providers. In Uganda, contraceptive stockouts, staff turnover, lack of regular supervision visits, and weak accountability systems hampered implementation of VRBFP.

It is important to identify creative solutions in a weak health system. In Nigeria, solutions included, for example, building the advocacy capacity of providers for motivating change at higher levels of the health system, as well as leveraging community groups – those linked to facilities – for filling immediate resource gaps. In Uganda, including the HUMC in orientation on VRBFP and supporting their own action plans yielded positive results as well as supplementing commodity shortages to ensure a full basket of FP options.

Strong And Supportive Supervision

Regular supervision is essential for ensuring rights adherence in facilities and can be optimized by integrating VRBFP components/activities into existing supervision checklists. In Northern Nigeria and Uganda, where the health systems are weak, supervision visits are underfunded, and often dependent on partner support. This challenges sustainability, creates an incentive for supervisors to prioritize the partner-supported initiative, and builds expectations for such funding in the future. In Uganda, supervision records indicate that even occasional supervision visits helped to strengthen counselling.

Need To Work At Multiple Levels

Working at the service delivery level is necessary but not sufficient for implementing VRBFP. In both countries, it was clear that it is critical to link facility-level work to the policy-level and (especially) the community-level, as these efforts are mutually reinforcing.

In the case of Nigeria, the community-level component bolstered facility-level improvements. For instance, FHCs worked to fill key health facility resource gaps – including mobilizing community member resources (in the absence of local government funds) for purchasing basic equipment needed for counselling (e.g., curtains and chairs) and service delivery rooms (e.g., commodity cabinet/cupboard). Committee members also conducted community outreach and sensitization visits with village heads, men, and women, including informing them of the standards of service they should come to expect at the facility. They also served as an accountability arm for facility services, overseeing ledger maintenance, as well as staff absenteeism (late arrival and early closures).

Likewise, in Uganda, work with the HUMC was important to reinforce the activities at service facilities. The HUMC identified issues that they should address related to service delivery, such as stock-outs and inadequate space in facilities. They also identified issues in the community that were important to FP and low contraceptive uptake, such as community attitudes and resistance towards family planning and lack of engagement by males. HUMC recognized the need for accountability for themselves, including the need to address irregular conduct of HUMC members, enhancing avenues for community input, and strengthening monitoring and supervision of the facility by HUMC members.

Additional Lesson From Nigeria

Successful adoption of the VRBFP approach requires translating theory into practice by identifying concrete ways that providers can take to apply rights principles in each element of family planning service provision. This was a key element of VRBFP capacity building efforts for both providers and supervisors; “role playing” key scenarios in which rights may be compromised, and teaching best practices for addressing weaknesses, empowered participants and gave them the skills required to improve the quality of services in their facility. This core element of capacity building produced both a self-assessed – measured through pre- and post-tests as well as focus group discussions – and observed – measured through provider-client clinical observations – mind- and behavior-shift.

Additional Lessons From Uganda

The expertise and knowledge of multiple actors during planning and project design is essential. A consultation on voluntary, rights-based family planning, led by the Government and RHU with support from the Sustainable Networks and Evidence Projects, anchored the project in context-specific challenges, and assured high-level buy-in.

RHU worked on the principle that “change starts at home” and conducted a comprehensive institutional rights audit on their own organizational practices and identified opportunities to strengthen their programs and policies. Assessing their own rights context helped RHU provide support to public sector facilities to improve voluntary, rights-based family planning services.

Conclusion

These first-of-their-kind projects in Nigeria and Uganda demonstrate how rights can be mainstreamed within health facility services. These two interventions addressed all rights and empowerment principles and yielded useful lessons for other countries interested in expanding VRBFP programming or improving VRBFP in their current health structures. Many of the lessons are shared across the two countries, including the need for rights literacy; attention to health systems issues; strong and supportive supervision; and working at multiple levels. Additionally, some unique lessons emanated from each country.

Operationalizing VRBFP in other contexts requires careful consideration of the broader health system, and simultaneous efforts across policy-, service delivery-, community-, and individual levels in order to creatively tackle deficiencies and externalities. This type of intervention has the potential to enhance client-centered focus in FP and to ensure that services adhere to rights principles, but systems-level challenges compromise scale-up and sustainability. With contextual adaptations, the model can potentially be evolved and applied more widely to systematically integrate rights into national family planning programming.

These interventions and associated implementation research studies provide valuable lessons learned on best practices for applying VRBFP programming, and crucial evidence on the value and effects of such approaches, that can guide other countries that want to ensure that their family planning programming is voluntary and rights-based. The use of common materials and program elements across the countries provide a solid basis for other countries to adapt and build on in their national and subnational programs. The measurement tool used in the studies, and modified based on experience using it, will be useful for programs to monitor adherence to VRBFP.

Keypoints

- These first-of-their-kind projects in Nigeria and Uganda demonstrate how rights can be mainstreamed within health facility services, with positive outcomes.

- The assessed feasibility and benefits of using voluntary, rights-based family planning programming and outcome measures in Nigeria and Uganda bode well for adoption of this programming approach in other geographies.

Disclosure

Ms Kaja Jurczynska reports grants from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, during the conduct of the study. Ms Diana Kabahuma Muhwezi reports grants from USAID, during the conduct of the study. Ms Kate Gray reports grants from USAID, during the conduct of the study. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development. New York: UNFPA; 1994.

2. Jacobson JL. Transforming family planning programmes: towards a framework for advancing the reproductive rights agenda. Reprod Health Matters. 2000;8(15):21–32.

3. Erdman JN, Cook RJ. Reproductive Rights. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Editor-in-Chief: Kris. Oxford: Academic Press; 2008:532–538.

4. Gruskin S, Mills EJ, Tarantola D. History, principles, and practice of health and human rights. Lancet. 2007;370(9585):449–455. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61200-8

5. International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). IPPF Charter on Sexual and Reproductive Rights. London: IPPF; 1996.

6. Department for International Development (DFID). Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. A Position Paper. London: DFID; 2004.

7. Mpinga EK, Verloo H, London L, Chastonay P. Health and human rights in scientific literature: A systematic review over a decade (1999-2008). Health Hum Rights. 2011;13(2):102–129.

8. Cottingham J, Kismodi E, Hilber AM, Lincetto O, Stahlhofer M, Gruskin S. Using human rights for sexual and reproductive health: improving legal and regulatory frameworks. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(7):551–555. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.063412

9. UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (UNCESCR). General comment No. 22 (2016) on the right to sexual and reproductive health (article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights). E/C.12/GC/22. 2016. Available from: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=E%2fC.12%2fGC%2f22&Lang=en.

10. Eager PW. Global Population Policy: From Population Control to Reproductive Rights. Wilmington, DE: University of Delaware Press; 2004.

11. FP2020 Rights and Empowerment Working Group. Family Planning 2020: Rights and Empowerment Principles for Family Planning. Washington, DC: FP2020; 2014.

12. World Health Organization (WHO). Ensuring Human Rights in the Provision of Contraceptive Information and Services: Guidance and Recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

13. Jain A, Hardee K. Revising the FP quality of care framework in the context of rights-based family planning. Stud Fam Plann. 2018;49(2):171–179. doi:10.1111/sifp.12052

14. Hardee K, Kumar J, Newman K, et al. Voluntary, Human Rights-Based Family Planning: A Conceptual Framework. Washington, DC: Futures Group and EngenderHealth; 2013.

15. Kumar J, Bakamjian L, Hardee K, Jurczynska K, Jordan S. Rights-based Family Planning. Brief in FP2020. 2018. Rights-sizing Family Planning. Available from: http://familyplanning2020.org/sites/default/files/Rights-sizing_Family_Planning_Toolkit_EN.pdf.

16. WHO and UNFPA. Ensuring Human Rights Within Contraceptive Service Delivery: Implementation Guide. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

17. Cottingham J, Germain A, Hunt P. Use of human rights to meet the unmet need for family planning. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):172–180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60732-6

18. Hardee K, Kumar J, Newman K, et al. Voluntary, human rights-based family planning: a conceptual framework. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45(1):1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00373.x

19. WHO. Monitoring Human Rights in Contraceptive Services and Programmes. Geneva: WHO; 2017a.

20. WHO. Quality of Care in Contraceptive Information and Services, Based on Human Rights Standards: A Checklist for Health Care Providers. Geneva: WHO; 2017b.

21. Tumlinson K, Okigbo CC, Speizer IS. Provider barriers to family planning access in urban Kenya. Contraception. 2015;92(2):143–151. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.04.002

22. Jain AK, RamoRao S, Kim J, Costello M. Evaluation of an intervention to improve quality of care in family planning programme in the Philippines. J Biosoc Sci. 2012;44:27–41. doi:10.1017/S0021932011000460

23. RamaRao S, Mohanam R. The quality of family planning programs: concepts, measurements, interventions, and effects. Stud Fam Plann. 2003;34(4):227–248.

24. Rodriguez M, Harris S, Willson K, Hardee K. Voluntary Family Planning Programs that Respect, Protect, and Fulfill Human Rights: A Systematic Review of Evidence. Washington, DC: Futures Group; 2013.

25. Sinai I, Anyanti J, Khan M, Daroda R, Oguntunde O. Demand for women’s health services in Northern Nigeria: a review of the literature. Afr J Reprod Health. 2017;21(2):96. doi:10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.11

26. PMA2020. PMA2020/Kaduna, Nigeria April – May 2018. Kaduna family planning brief. 2018. Available from: https://www.pma2020.org/sites/default/files/ng-kaduna-r5-v3-20180923.pdf.

27. National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International; 2014.

28. Sinai I, Nyenwa J, Oguntunde O. Programmatic implications of unmet need for contraception among men and young married women in northern Nigeria. Open Access J Contracept. 2018;2018(9):81–90. doi:10.2147/OAJC.S172330

29. Ankomah A, Anyanti J, Adebayo S, Giwa A. Barriers to contraceptive use among married young adults in nigeria: a qualitative study. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2013;3(3):267–282. doi:10.9734/IJTDH/2013/4573

30. Kaduna State Government. Costed Implementation Plan for Family Planning 2016 – 2018. 2016. Available from: https://www.familyplanning2020.org/sites/default/files/Palladium-Kaduna-CIP-and-Activity-Matrix_9.28gs.pdf.

31. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda and Rockville, Maryland, USA: UBOS and ICF; 2018.

32. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Uganda National Service Delivery Survey 2015. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS; 2015.

33. Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC). The 19th Annual Report to the Parliament of the Republic of Uganda 2016. Kampala: UHRC; 2016.

34. Kibira SPS, Muhumuza C, Bukenya JN, Atuyambe LM. “I Spent a Full Month Bleeding, I Thought I Was Going to Die … ” A qualitative study of experiences of women using modern contraception in Wakiso District, Uganda. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0141998. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141998

35. Mugisha JF, Reynolds H. Provider perspectives on barriers to family planning quality in Uganda: a qualitative study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2008;34:37–41.

36. Chekweko J 2016. Rights-based Family planning in Uganda.

37. Wright K, Boydell V, Muhangi L, et al. 2017. Measuring rights-based family planning service delivery: evidence from health facilities in Uganda.

38. Hardee K. Measuring Rights-Based Family Planning Service Delivery: Evidence from Health Facilities in Uganda. PowerPoint slides. Washington DC: Evidence Project; 2017Available from:http://evidenceproject.popcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Hardee-IUSSP-RBFP-Uganda-FINAL-10.31.17-.pdf.

39. Kumar J, Bakamjian L, Harris S, et al. Voluntary Family Planning Programs that Respect, Protect, and Fulfill Human Rights: Conceptual Framework Users’ Guide. Washington, DC: Futures Group; 2014.

40. The RESPOND Project. Checkpoint for Choice: An Orientation and Resource Package. New York: EngenderHealth/The RESPOND Project; 2014.

41. Oguntunde O, Surajo IS, Dauda DS, Salihu A, Anas-Kolo S, Sinai I. Overcoming barriers to access and utilization of maternal, newborn and child health services in northern Nigeria: an evaluation of facility health committees. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:104–114. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2902-7

42. Ministry of Health, Uganda (UMOH). Uganda Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan 2015-2020. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2014.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.