Back to Journals » International Medical Case Reports Journal » Volume 14

Fatal Autoimmune Anti-NMDA-Receptor Encephalitis with Poor Prognostication Score in a Young Kenyan Female

Received 2 April 2021

Accepted for publication 12 May 2021

Published 24 May 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 343—347

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S311071

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ronald Prineas

Supplementary video of "Fatal Autoimmune anti-NMDA-receptor Encephalitis" [ID 311071].

Views: 6327

Joe Rakiro, Dilraj Sokhi

Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University Medical College of East Africa, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence: Dilraj Sokhi Room 405, 4th Floor East Tower Block, Third Avenue Parklands, P.O. Box 30270, Nairobi, 00100 GPO, Kenya

Tel +254 710 559 541

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Auto-immune N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis (NMDARE) is a relatively recently described cause of acute encephalopathy with very few reports from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). We report a case of NMDARE in a young Kenyan female who was transferred to our facility with headaches, insomnia, behaviour changes and latterly pathognomonic orofacial dyskinesias. We comprehensively ruled out infectious and other inflammatory/auto-immune causes. She was diagnosed with NMDARE by positive antibody testing in serum and cerebrospinal fluid and changes on brain magnetic resonance imaging. She was immunosuppressed with high-dose steroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, plasma exchange and rituximab, and showed signs of neurological improvement clinically and radiologically. Unfortunately, she succumbed to septic shock from prolonged intensive care. This is the first report of NMDARE in an indigenous patient from the eastern SSA. The majority (> 80%) of patients are either left with mild disability or make a full recovery after NMDARE, but some factors – which comprise the NMDARE One-Year Functional Status (NEOS) prognostication score – can adversely affect outcome, as was the case in our patient.

Keywords: auto-immune encephalitis, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Auto-immune encephalitis caused by antibodies against the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor GluNR1 subunit (NMDARE) is a rare and relatively recently described but treatable cause of acute encephalopathy, more common in children/younger adults and in females.1 The clinical presentation is heterogeneous, but psychiatric and behavioral symptoms occur in 90% of cases at onset and can mimic primary psychiatric disease.2 As the disease progresses, a myriad of neurological symptoms may arise, some of which are pathognomonic, eg, abnormal movements and insomnia.1 Misattribution to an infectious aetiology is more likely in tropical countries,3 compounded by lack of awareness of NMDARE and unavailability of diagnostic services, particularly cell-based antibody testing and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Treatment is with immunotherapy, plus surgical teratoma removal if found, and early treatment is known to be associated with better outcomes. Observational studies have shown that over 80% of NMDARE cases recover fully or have mild residual functional deficit [ie, modified Rankin Score (mRS) of 0–2] at 24 months.4 However, some patient-, disease-, and/or treatment-related factors predict poorer outcomes, and are incorporated in the NMDARE One-Year Functional Status (NEOS) prognostication score.5 There are very few published case reports of NMDARE from Africa; our literature review reveals only one report each from West6 and South7 Africa.

Materials and Methods

We report here the first indigenous case of NMDARE from East Africa who we treated but had a poor outcome as prognosticated by a high NEOS score at outset.

Case Presentation

A 17-year-old black African female initially presented to a local clinic with 2 weeks of gradual-onset bi-frontal headache, insomnia, and subjective fevers. She was treated for non-specific infection – despite no documented fever or microbial isolates – with empiric antibiotics for 10 days during which she also developed restlessness and third-person auditory hallucinations. She was then referred to a psychiatrist who diagnosed her with an acute schizoaffective disorder given the additional history of underlying psychological stressors (it was the death anniversary of her mother, and her final high-school national examinations were imminent). She was admitted and treated with psychotropic medication, but after five days she developed documented fevers, orofacial dyskinesias with tongue-biting, and agitation, and she was additionally treated for neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). She then became comatose and was thus transferred to our tertiary referral hospital.

On our initial assessment, she had a temperature of 39°C and tachycardia; neurologically her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 7/15, she had grimacing, tongue biting, bruxism, hyper-salivation and abnormal arm movements which were difficult to classify (Figure 1, Supplementary Video S1). She was intubated, mechanically ventilated and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

|

Figure 1 Still picture of Supplementary Video S1 highlighting upper limb tremors and orofacial dyskinesias. |

We immediately ran investigations comprehensive blood and/or urine tests for infection, auto-immune disease (including vasculitis) and toxic causes (including porphyria), also comprising polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for tropical fever pathogens (human immunodeficiency virus, Treponema pallidum, malaria, Leptospira, rickettsia, dengue, West Nile, chikungunya and rabies viruses – with additional testing in saliva and neck hairline skin biopsies for the latter), contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the head, chest and abdomen which were all normal/negative.

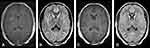

Examination of her cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed elevated pressures, and white cell count of 115/mm3, 98% lymphocytes, with negative PCR for bacterial, tuberculosis and herpes (simplex and varicella zoster) meningo-encephalitis pathogens (including on repeat CSF on day 2). Contrast-enhanced MRI brain scan demonstrated leptomeningeal enhancement (Figure 2A) with corresponding sulcal hyperintensities (Figure 2B) and serial electroencephalography (EEG) showed non-specific diffuse slowing with no epileptiform discharges.

She was initially treated for viral encephalitis, but this was stopped after two negative PCRs in CSF. After two further independent neurology opinions in addition to the primary neurologist (author DSS), we diagnosed the patient with probable NMDARE as defined by international criteria1 and commenced immunosuppression with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) 1 gram/day for five days and concurrent intravenous immunoglobulins. The orofacial and upper limb movement disorders were controlled with a combination of oral levetiracetam and tetrabenazine, midazolam and propofol infusions, and maxillo-mandibular fixation. On day 7 both serum and CSF autoimmune encephalitis panels returned positive for antibodies against the NMDA receptor, giving a definite diagnosis of NMDARE. MRI pelvis did not show any ovarian or extra-gonadal teratoma.

At day 15 repeat MRI brain scan showed almost complete resolution of the meningeal enhancement (Figure 2C) and sulcal hyperintensities (Figure 2D) but her GCS remained persistently low at 8/15 and her unrelenting dyskinesias required higher sedation requirements. We repeated the IVMP course now with concurrent plasma exchange and weekly rituximab dosed at 375mg/m2 body surface area. Her ICU stay was complicated by right brachial deep vein thrombosis treated with low-molecular weight heparin, and tongue maceration that required surgical debridement. She had both tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes fixed due to the prolonged ICU admission.

During the fourth week, she developed high-grade fevers due to multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae, isolated from tracheal aspirates and the tracheostomy site. Despite timely initiation of appropriate intravenous antibiotics including carbapenems and continued debridement of the tracheostomy site, the patient went into septic shock leading to multi-organ dysfunction and succumbed 30 days into her hospital stay.

Discussion

Our adolescent patient’s clinical course followed what is recognised to be more common in children affected by NMDARE, ie, abnormal movements, insomnia, and irritability with progression to coma within 4 weeks.1 Her initial presentation being diagnosed as a primary psychiatric disease is not unusual, including NMDARE mimicking NMS,8 but did lead to some delay in reaching the diagnosis. In our setting, infective and inflammatory causes of encephalitis are more common, and therefore feature in our institutional encephalitis management protocol which we have previously demonstrated to expedite NMDARE diagnosis in an expatriate patient, who eventually had a very good clinical outcome.9

CSF and MRI brain findings in NMDARE patients can be varied and may also mimic infectious aetiologies, but we excluded these early on. CSF leucocytosis and leptomeningeal enhancement, as in our patient, are known to occur in this condition.1,10 We followed international guidelines for immunosuppression and her MRI even improved after the first two weeks, and we transitioned to second-line immunosuppression with rituximab because of persistent coma and the refractory oral dyskinesias,11 the latter of which eventually required partial lingual excision and mechanical jaw fixation. In retrospect, we should have considered additional multi-modal pharmacological management of the patient’s agitation and dyskinesia which have been demonstrated to be useful in managing NMDARE, eg, quetiapine12 and clonidine.13

We encountered limitations in our settings. Our facility, nor any other in the region, does not have long-term ICU EEG monitoring. We performed serial EEGs and the clinical features of these persistent dyskinesias and upper limb tremors were not in keeping with seizures but could not be ruled out, so we continued with levetiracetam treatment. Another limitation was the unavailability of positron emission tomography to look for more occult ovarian or extra-gonadal teratomata, but in most NMDARE cases CT and MRI imaging is sufficient.

Mortality risk in ICU settings is high in resource-poor countries, including Kenya,14 and is even higher in auto-immune encephalitides managed in ICU, with multi-organ dysfunction, severe sepsis and tracheostomy requirements being the main factors, all of which were present in our patient.15 Our patient succumbed to septic shock, which reflects the absolute necessity for fastidious ICU management that may last several months in NMDARE patients especially with the more aggressive form of the disease. Additionally, however, our patient would have had a poor outcome primarily because of her disease severity: we retrospectively calculated her posthumous NEOS score and it was the highest possible at 5 (one point each for “ICU admission required”, “no improvement after 4 weeks of treatment”, “no treatment in first 4 weeks of onset”, “abnormal MRI” and “CSF white cell count >20 cells/µL”). This score predicted a mortality risk of almost 20%, or risk of severe disability of over 40%,5 and at the time would have allowed us to have more informed discussions about prognosis with the family.

Conclusion

We have described the first NMDARE case from eastern SSA. We recommend early clinical suspicion, timely appropriate immunotherapy, and management of complications including those related to prolonged ICU stay to improve outcomes. Additionally, our case:

- taught us that local awareness of the condition needs to be improved across the spectrum of healthcare workers to whom such a patient may present given the myriad of possible symptoms at onset;

- highlights the challenges faced in our settings, including high morbidity due to factors associated with prolonged ICU admission, and the diagnostic limitations such as unavailability of prolonged EEG monitoring;

- the usefulness of the NEOS score in predicting outcome.

Data Sharing Statement

The clinical history and imaging data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Research Ethics and Consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study is exempted from our formal institutional ethics review given it is a case report. Informed and written consent for the case details to be published was obtained from the registered next of kin (the father) of the patient after the patient’s demise, and the consent form is filed in patient’s medical case file. The authors have removed all patient identifiable information from the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Dr. Sheila Waa (consultant neuro-radiologist) for providing the neuro-imaging pictures, and Dr. Juzar Hooker, Dr. Peter Mativo and Dr. Sylvia Mbugua (consultant neurologists) for their clinical input with the case, all at the Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This case series did not receive any specific funding. The cases have been compiled as part of authors’ current employment under the Aga Khan University Medical College of East Africa, Faculty of Health Sciences.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work and that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

1. Dalmau J, Armangue T, Planaguma J, et al. An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1045–1057. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30244-3

2. Kayser MS, Titulaer MJ, Gresa-Arribas N, Dalmau J. Frequency and characteristics of isolated psychiatric episodes in anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1133–1139. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3216

3. Wong D, Fries B. Anti-NMDAR encephalitis, a mimicker of acute infectious encephalitis and a review of the literature. IDCases. 2014;1(4):66–67. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2014.08.003

4. Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor encephalitis: a cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157–165. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1

5. Balu R, McCracken L, Lancaster E, Graus F, Dalmau J, Titulaer MJ. A score that predicts 1-year functional status in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology. 2019;92(3):e244–e252. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006783

6. Gbadero DA, Adegbite EO, LePichon JB, Slusher TM. Case presentation of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in a 4-year-old boy. J Trop Pediatr. 2018;64(4):352–354. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmx070

7. Roos IB. Autoimmune encephalitis: a missed diagnostic and therapeutic opportunity. African J Neurological Sci. 2017;36(2):66–79.

8. Wang HY, Li T, Li XL, Zhang XX, Yan ZR, Xu Y. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis mimics neuroleptic malignant syndrome: case report and literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:773–778. doi:10.2147/NDT.S195706

9. Sokhi DS, Bhogal OS. Autoimmune encephalitis is recognised as an important differential diagnosis in a Kenyan Tertiary Referral Centre. BMJ Mil Health. 2020;166(5):358. doi:10.1136/jramc-2019-001338

10. Bacchi S, Franke K, Wewegama D, Needham E, Patel S, Menon D. Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a systematic review. J Clin Neurosci. 2018;52:54–59. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2018.03.026

11. Guasp M, Dalmau J. Encephalitis associated with antibodies against the NMDA receptor. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;151(2):71–79. doi:10.1016/j.medcli.2017.10.015

12. Schumacher LT, Mann AP, MacKenzie JG. Agitation management in pediatric males with anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor encephalitis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(10):939–943. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0102

13. Mohammad SS, Jones H, Hong M, et al. Symptomatic treatment of children with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(4):376–384. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12882

14. Lalani HS, Waweru-Siika W, Mwogi T, et al. Intensive care outcomes and mortality prediction at a National Referral Hospital in Western Kenya. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(11):1336–1343. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201801-051OC

15. Nelson SE, Nyquist PA. Autoimmune encephalitis in the intensive care unit. Neurointensive Care Unit. 2020;249–263.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.