Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 13

Experiences from the Field: A Qualitative Study Exploring Barriers to Maternal and Child Health Service Utilization in IDP Settings Somalia

Authors Mohamed AA , Bocher T, Magan MA , Omar A, Mutai O, Mohamoud SA, Omer M

Received 26 July 2021

Accepted for publication 12 November 2021

Published 25 November 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 1147—1160

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S330069

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Editor who approved publication: Dr Everett Magann

Adam A Mohamed,1,2 Temesgen Bocher,1 Mohamed A Magan,1 Ali Omar,1 Olive Mutai,1 Said A Mohamoud,3 Meftuh Omer1

1Save the Children International, Mogadishu, Somalia; 2Department of Public Health, Institute of Health Sciences, Baskent University, Ankara, Turkey; 3Department of Research, Somali Institute for Development Research and Analysis (SIDRA Institute), Garowe, Somalia

Correspondence: Adam A Mohamed Email [email protected]

Background: In Somalia, maternal and child health service utilization is unacceptably low. Little is known about factors contributing to low maternal and child health service utilization in Somalia, especially in internally displaced people (IDP) settings. This study aimed to understand barriers to the use of maternal and child health-care services among IDPs in Mogadishu.

Methods: A total of 17 in-depth interviews (IDIs), 7 focus group discussions (FGDs), and field observations were conducted on lactating/pregnant mothers, health-care providers, traditional birth attendants (TBA), and IDP camp leaders. The socio-ecological model (SEM) framework was employed for the categorization of barriers to healthcare utilization and further analysis was conducted to understand the major types and nature of barriers.

Results: Using the SEM, the following major barriers that hinder maternal and child health service utilization were identified. Low socio-economic, lack of decision making power of women, TBA trust, poor knowledge and awareness on pregnancy danger signs, fear of going to unfamiliar areas were identified barriers at individual level. Traditional beliefs, male dominance in decision making, and lack of family support were also identified barriers at interpersonal level. Security and armed conflict barriers and formidable distance to health facility were identified barrier at the community level. Lack of privacy in the facility, transportation challenges, poor functional services, negative experiences, closure of the health facility in some hours, and lack of proper referral pathways were identified barriers at organizational or policy level.

Conclusion: Overall, various factors across different levels of SEM were identified as barrier to the utilization of maternal and child health services. Hence, multi-component interventions that target these complex and multifaceted barriers are required to be implemented in order to improve maternal and child health services utilization among IDP in Mogadishu, Somalia.

Keywords: barriers, utilization, maternal and child health, pregnant and lactating, Somalia

Background

Maternal morbidity and mortality remain a great public health and humanitarian concern. World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 810 mothers die every day due to pregnancy or childbirth-related causes and additional 6500 newborn babies die, which is unacceptably high (WHO, 2019). Most of the causes are either preventable or treatable. There is a considerable gap of maternal mortalities and morbidities across countries around the world. Around 94% of all maternal deaths occur in low and lower middle-income countries, which reflects access and utilization inequalities between rich and poor communities (WHO, 2019). For instance, the Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) as average in very low-income countries is 462 per 100,000 live births compared to 11 per 100, 000 live births in high-income countries of the world (WHO, 2019). Somalia is among the 15 countries that WHO marked as very high alert countries for maternal deaths.1 Somalia has one of the worst maternal conditions in the world. The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is 692/100,000 live births where 1 in 20 women would die from pregnancy-related causes during their reproductive lifetime.2 Four in 100 Somali children die during the first month of life, eight in 100 before their first birthday, and 1 in 8 before they turn to five.3

Access to healthcare services is vital to everyone, including host communities, IDPs, and other families relocated to new places. However, when people migrate from one location to another, like rural to urban settings, for any reason, they always face challenges that can hinder their ability to access the health services. Approximately 2.6 million Somalis are currently displaced within their own country. The largest concentration, around half a million, are in the Somali capital, Mogadishu. Some families were displaced nearly 30 years ago, whereas others continue to arrive in the city daily due to conflict and natural disasters. Families that moved to these areas live in precarious conditions and are unable to meet basic needs due to inconsistent health service provision or exclusion from accessing humanitarian support due to the conflicts in the city.4

Little is known about factors contributing to low maternal and child health service utilization in Somalia, especially in the IDP settings. Health service utilization is the quantification or description of the use of services by persons to prevent or cure health problems, promote maintenance of health and well-being, or obtaining information about one’s health status and prognosis (Bazie G, 2017). Access is “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes.” It is the degree to which individuals can obtain needed healthcare services from the existing healthcare system.5

Barriers to healthcare access are those factors that prevent individuals either from accessing the care they need or from receiving the level of care they need in terms of adequate and quality. Prior studies have identified several barriers to care. These include personal barriers—individual perceptions and beliefs of needs; financial barriers –low income is viewed as a barrier to health care; organizational barriers such as long-distance, transportation, long waiting list; referral barriers– from primary to secondary providers; and communication barriers–migrants moving to new places and environments.6 This study aims at creating a better understanding of the existing barriers to the use of maternal and child health-care services among IDPs.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

The study followed McLeroy’s Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) to explore barriers to maternal and child health service utilization. The socio-ecological model focuses on individual, community, facility, and policy-level determinants of health and interventions. It emphasizes how multiple levels like interpersonal, community, institutional, environmental, and public policy can influence individual behavior and health.

Study Setting

The study was conducted in Deynile, Dharkenley, and Kahda districts located in Benadir Regional Administration (known as Mogadishu or Hamar) that contain 17 districts. There are 2.6 million displaced people in Somalia and Benadir Region hosts the highest number of Somalia IDP communities and the majority of the displaced communities live in these selected three districts. Deynile is the biggest district with 15 health facilities/health posts across the district in which Save the children manages 2 of these health facilities, whereas Dharkenley has 6 health facilities/posts where Save the Children runs one of them, and Kahda has 6 health facilities or health posts and save the children does not work on these 6 health facilities or health posts.

Study Design

The study employed a cross-sectional, exploratory design and employed purely qualitative techniques for data collection. This study collected primary data generated from focus group discussions (FGDs), In-depth Interview (IDIs), using semi-structured guides, and field observation checks.

Research Participants

The study participants were drawn from different segment of the population considering different dimensions that explain low utilization of maternal and child healthcare services. Participants were selected based on the information they possess and the individual relevance to maternal and child health service uses. For the purposes of this research, to ensure representativeness, and to understand the multifaceted levels of the study framework within a society and how individuals and the environment interact within a social system, we classified the participants into Four groups, which were “Lactating/Pregnant mothers”, “Traditional Birth Attendants”, “IDP camp leaders” and “health-care providers”. The first group here “Women” refers to mothers who were pregnant or lactating during the study period. The second group “Traditional Birth Attendants” refers to only women who practice traditional birthing or provide home-based deliveries. The third group “IDP camp/community leaders” which refers to both men and women who are camp/community leaders and husbands of one of the lactating or pregnant mothers. The fourth groups “Health-care providers” refers to health professionals including doctors, nurses, midwives, health-care managers, and health policy planners, regional or district health directorates, midwifery associations, and humanitarian organization workers.

Sampling and Recruitment Procedures

The study applied purposive sampling strategy for recruiting study participants. “Health-care providers” were selected based on their knowledge and experience of healthcare service provision, “pregnant or lactating mother”, “traditional birth attendant”, and “IDP camp leaders” were selected purposively as well. The required sample size was determined based on data saturation; the point where no new information is observed in the data. The study investigators carried out 7 FGDs and 17 IDIs. An information sheet explaining the purpose of the research and procedures that will be used were explained to the participants.

Data Collection Methods

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and In-depth Interviews (IDIs) followed by field notes were the main data collection methods. Seven FGDs comprising 3 Health Workers-FGD (32 participants (62.5% female)) and 3 pregnant and lactating mothers (32 mothers) from the three study districts, and one FGD from IDP camp leaders (8 gatekeepers) in the three districts. Each Focus group discussion lasted 1 to 1.30 hours and the ending point of the discussion was assumed when there is/are no new issues or ideas seem to arise. Seventeen (65% female) IDIs involving all of the four study groups which were “pregnant and lactating mothers”, “Traditional Birth Attendants”, “husband and IDP camp leaders”, and “health-care providers” were conducted. Each interview lasted 30 minutes to 1 hour and ended when the peak of saturation was reached.

Research Instruments

We adopted two interview guides for this study “Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and In-depth Interview (IDIs) guides”.7 The two instruments were designed in the form of thematic open-ended topic guides to ensure the data quality and to elicit all interdependent factors to maternal and child health service utilization. Before conducting the Focus Groups and In-depth Interview, we carried out one focus group discussion in Waberi district IDP camp and one interview with health-care providers. To ensure the reliability of the study tools, we engaged a timely adjustment and review of the tools, and all needed proper amendments were made to make sure that the tools are eliciting a precise answer to the right questions. The study tools were designed to highlight how multiple layers of individual, family, community, and institution-related factors influence utilization of maternal and child health services.

Data Analysis

This study used qualitative thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke to assess barriers that contribute to low utilization of maternal and child health-care services across various levels of the socio-ecological model (SEM) framework.8 We used this model for categorization and understanding the existing barriers. The reason for using this model was to situate and explain how diverse layers in SEM can be bridged to five barrier levels spanning from intrapersonal to policy levels.

The first step involved transcribing and reading of transcripts and field notes for understanding. Two qualified persons who were fluent in English and Somali transcribed the audio from the recorded In-depth Interviews (IDIs) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) supplemented by the investigators’ field notes. The Somali transcripts were then cross-checked. Another Somali person who is fluent in English cross-checked the accuracy and completeness of the translations made before data was ready for coding among the main labels. The interview transcripts that were cross-checked were then exported to NVivo 9 qualitative data analysis application.

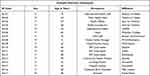

The study used both deductive and inductive data coding. Codes we labelled according to socio-ecological model (SEM) framework. The nature of socio-ecological model is to focus on individual, community, facility, and policy-level determinants of health and interventions. It emphasizes how multiple levels like interpersonal, community, institutional, environmental, and public policy can influence individual behavior and health. The study investigators produced a range of themes and categories that were grouped into the four themes according to socio-ecological model (SEM) framework and seventeen categories as described in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Thematic Network Analysis Framework (According to Socio-Ecological Model) |

Ethics

Our ethical approach followed Declaration of Helsinki and will comply all its guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ministry of Health and Human Services (Reference number: MOH&HS/DGO/1600/12/2020). All participants provided informed consent before their participation, after it was explained to them that their participation was voluntary, and that the information obtained will only be used for the purpose of this research and for the publication of anonymised responses. All efforts were made to ensure confidentiality of their responses.

Results

Several themes emerged during our data analysis. According to McLeroy’s socio-ecological model, themes were grouped into the five themes and fifteen categories. The emerging barriers include; individual-level barriers (economic barriers, lack of decision making power of women, TBA trust, poor knowledge and awareness on pregnancy danger signs, and fear of going to unfamiliar areas), interpersonal-level barriers (cultural and traditional beliefs, male dominance in decision making, and lack of family support), community-level barriers (exposure to armed conflicts-security barriers and distance and transportation barriers), organizational-level barriers (lack of privacy in the facility, poor functional services, negative experiences, and closure of the health facility in some hours), and policy-level barriers (lack of proper referral pathways). Tables 2 and 3 summarize the basic characteristics of the primary study participants and their grouping.

|

Table 2 Basic Characteristics of Focus Group Discussion Participants |

|

Table 3 Basic Characteristics of the In-Depth Interview Participants |

Theme 1: Individual Level Barriers

Five categories that formed individual-level barriers emerged during the data analysis. According to McLeroy’s socio-ecological model framework: Economic, lack of decision making power by women, trust in TBAs, poor knowledge and awareness on pregnancy danger signs, fear of going to unfamiliar areas were all grouped to form individual-level barriers. Majority of the mothers were illiterate, did not have enough knowledge about the benefits and danger signs of maternal health services and instead believed the traditional birth attendants as their saviors.

Economic Barriers: Lower-Level Household Income

Economic barriers to maternal healthcare services were reported by many participants. Most of the mothers were women of low socio-economic status who were illiterate and unemployed. They stated that although maternal health services are free (in some places), they still have difficulties raising the transportation costs. Some mothers also complained about being told to buy medicine from outside the health facility of which they cannot afford. Their husband’s income is not sufficient for their basic needs so, they cannot pay for both the transportation and medication costs as some of the participants stated below:

It’s difficult for a mother to purchase prescribed medicines or buy a milk to her child so how do you expect mothers to go to the health facilities when they have no money. We are suffering here, and we do not get money. The expenses are too high, we are unable to afford it and they (MCH staff) won’t send for you an ambulance in case you call them, we barely can feed ourselves, so you are forced to give birth at home since you can’t afford the travel and drug expenses. (Lactating mother FGD-7, Dharkenlay)

Women also reported that the only way they can get money is to ask their husbands who cannot cover all the expenses. Most of the husbands in the IDP communities do not have a source of income that can sustain the household’s basic needs income to cover the family’s basic needs as a pregnant mother living in Deynile district stated:

My husband is a laborer, and I don’t work, what he earns is not even sufficient for our basic needs. I cannot deliver at a hospital or go for checkup because when you go to the health facilities all services are free, but you are told to buy medicine from outside ie, private pharmacies. For instance, I wanted to visit the health facility yesterday, but I could not because of lack of finances. I asked people to lend me some money for transportation, but I was unable to receive the money from anyone. I had to walk to the area where you have access to transportation. My children were at home by themselves and because I was unable to go to the clinic I just came back home. (FGD-5, Pregnant mother, Deynile)

Health-care providers also recognized that low socio-economic status of IDP families can be an obstacle for mothers to access the available services. A female community health worker explained:

People here are poor. In general, the living conditions are difficult for them some of the mothers cannot even provide food for their families and most of the husbands are jobless; they do not work for their families so they cannot get money to buy medicine and to go the MCH since its far away. If the mother feels somehow ill, and need to seek care, she will need to inform her Father or husband as they are financially responsible for her, if they cannot afford, then she would not have any access to health care. (IDI-09, Female, CHW, Kahda)

Another health-care provider illustrated:

There are two groups among women in the IDPs. One is the less fortunate and the other is the fortunate. The biggest reason as to why some women do not seek healthcare at health facility is due to the financial difficulties they are facing. (IDI-06, Female, Policy-maker)

Lack of Decision-Making Power of Women

Generally, women are deprived of their right to make decisions on their need for maternal and child health services. It is their husbands and other family members (mostly parents) who make the decision whether women should access maternal and child health services or not. Since women are not financially independent, they rely on their husbands and other family members for financial support, so they have to discuss with them before deciding to go to the health facility. Mothers also reported that they are caregivers and cannot leave the children behind to seek care since their husbands will not allow for them.

Sometimes its men who refuse their wives to give birth at the MCH, they say there is no need to take them to the hospital, they only need to be recited in Quran and the delivery will be easy for them. (Male, IDI-05, Policy-maker)

Participants also reported that since teenage mothers do not have enough knowledge and experience about maternal services, their mothers or husbands make decisions for them. When they develop some complications and they are referred to the main hospitals, her family members may refuse her to go the hospital.

SCI staff stated that:

When the mother has a complication identified by the health workers and they are advised to be referred to one of the city’s main hospitals for further advanced treatments, but because of lack of her own choice, especially when the mother is a teenage, their family and relatives would refuse and would take her back home. Pregnant women do not have the decision and choice to seek healthcare. They cannot decide themselves. (Female, IDI-03, Health Officer)

Women’s decision to utilize maternal health-care services or to give birth at the health facilities was dependent on their husband’s approval and acceptance.

Some men prefer their wives to give birth at home because they don’t want their wives to be assisted by male health workers, when the wife is giving birth at home the husband is comfortable with the traditional birth attendant since she is old woman, but when she is giving birth at the health facilities, he is not sure whether its male or female health worker who is attending to his wife. (IDI-16, Traditional Birth Attendant)

TBA Trust and Acceptance

Traditional Birth Attendants still remain the first choice for pregnant women in Somalia. Trust in TBA and acceptance by the community are the most cited reasons that mothers choose home delivery. Some mothers stated that they do not have to pay (TBAs) right after they give birth, but you can pay later when you get money, or you do not pay anything they assist you for free. Some of the mothers happen to be a close relative to the traditional birth attendant, they would not want to take the money to somewhere else and they believe she will care for her wellbeing more than anyone else. Mothers also believe that caesarean delivery is something obvious in the health facilities and hence preferred home delivery.

I have given birth all my four children at home with the help of traditional birth attendant and didn’t visit a health facility for checkup, Alhamdulillah (Praise be to God) nothing has happened to us we are all healthy and I don’t want waste my time by going there. Do you know why we prefer the old mothers (TBA, Umuliso-dhaqameed in Somalia)? It’s because traditional birth attendants will come to your home you don’t need to pay fare and they are always available, but the health facilities are far away you have to pay transportation money and they only operate during the day. (IDI-14, Lactating Mother, Kahda)

Most IDP mothers give birth at home with TBAs because they trust them, and they cannot afford going to a health facility mostly. They usually seek our services when the TBA has deemed the woman in a critical condition and referred to our healthcare facility. (FGD-2, Female, Nurse)

Even husbands believe that giving birth is a natural process and you do not need to go the health facility if you are not sick. Their mothers used to give birth at home with the help of a TBA and nothing has happened to them, they want to follow the same route as their mothers and grandmothers. As family head husband explained:

What we are familiar with is the Umuliso-dhaqameed (TBAs) because they historically supported the delivery of our mothers. This is what we had since earlier times. MCH is new and we will see its goodness in the future. I don’t send my wives to health facilities during delivery because we have an experienced old mother with a lot of experiences. (IDI-17, Husband)

Lack of Knowledge on Pregnancy Danger Signs and Benefits of Maternal Health Services

Lack of health education or poor awareness on labor outcomes was another issue which was reported by many study participants. Most of the mothers were not educated so, they do not understand much about the awareness they were given. They do not understand the risks associated with home delivery and the benefits of visiting and giving birth at the health facilities. Some of them fear blood transfusion and choose to give birth at home which can lead to death due to excessive bleeding.

Due to lack of knowledge and understanding of the importance of health care, some mothers do not seek treatments. Mothers were not convinced about the benefits of seeking health care services while others do not even know about the MCH services. They always stay at home while they are still sick. (IDI-02, Male, Policy-Maker)

Due to lack of health education or awareness about the benefits of health facilities, mothers are not aware on how the health facilities services can prevent them from complications and contribute to safer pregnancy as IDP camp leader stated:

Most of the women in the IDPs are not aware of the possible risks of giving birth at home, its associates with infant death, and sometimes the mother might die of excessive bleeding and the old women (TBAs) don’t have medicine they just use traditional methods which sometimes are not helpful. (FGD-4, Female, Camp leader)

Another health-care provider also reported that due to lack of health education, mothers even are not aware of the services are available in the health facilities, as community health worker elaborates:

Some mothers would stay at home during the labor waiting until last minute when the baby is close and maybe even then there could be some complications and on the way to the health center the mother could lose her life. This is because of their awareness level. They don’t know the dangers of delivering at home. (FGD-2, Nurse, Kahda)

Due to lack of awareness or health education some of the mothers believe that the vaccines cause complications, and they refuse to take it. One participant illustrates below:

Birthing is natural, and you need Allah to save you. Wherever you deliver, it would be same. I prefer to go to the old woman (TBA) because xarunta (health facility) has different practices like they ask you to take vaccine or to your child which is not good. Vaccines are also medicines that can harm you. When you deliver at home, it is much safer I hope. (IDI-14, pregnant woman)

In the same way, some of the health-care providers and health policy-makers also illustrated that women do not have any idea on the benefits of labour outcomes. A policy-maker made the following conclusion:

There are many women who choose not to go to the clinic to give birth, but I believe they do not have enough knowledge of the benefits of seeking services at the clinics. They (women) lack awareness. Woman cannot seek maternal health care from the health facilities if she does not know the benefits of seeking maternal health care at these facilities. There needs to be more awareness raising. Many women seek healthcare when they are in dire conditions. They do not understand that they can seek healthcare when they are deemed healthy also … all pregnancies are risk and they do not know that they should seek care throughout their pregnancy. (IDI-05, Male, policy-maker)

Fear of Going to an Unfamiliar Setting

Some of the mothers never went to a health facility, especially teen mother. The community or other mothers give them wrong information about delivering health facilities which creates fear to go to the health facility. They are more familiar with home delivery and the assistance of TBAs.

I am new to this IDP and the nearby MCH. I need to settle and feel home for some months. I have a fear to visit the health facility for now. I do not know that facility and the people. For instance, what about if male nurse assists my delivery? I am worried about been assisted by a male health worker if I go to the health facility. (FGD-05, Pregnant woman, Deynile)

Health policy-makers also reported that it is scary for the pregnant mother to attend maternal services for the first time as they did not experience their mothers or grandmothers attending health facilities in their lifetime. So, they believe there is no need to go to MCH.

Teen mothers have little knowledge regarding general maternal health services. It is very hard for them to attend ANC or delivery for the first time since they were not familiar with the health facility. They are not familiar with the MCH. Their mothers only tell to connect with the TBAs. They have that information so how can they attend unfamiliar settings for the first time. (IDI-01, Female, Policy-maker)

Interpersonal Level Barriers

Cultural and Ritual Traditional Beliefs

Cultural and traditional beliefs influence the utilization of maternal and child health services. Mothers believe in traditional norms and customs. Most of them are supported by TBAs who are familiar with their culture when giving birth. Their work is adapted and strictly bound to the social and cultural table to which they belong.

When I ask them why they do not want to give birth at the hospital, most of them (women) say: this is our culture and we inherited from our mothers. Their mothers, grandmothers and great grandmothers never gave birth at a hospital and they have faced no problems; they were all assisted by traditional birth attendants, so why do we have to give birth at the health facilities. There is nothing different with us. (FGD-02, Female, Midwife, Kahda)

Women have their practices and beliefs, and they seem to be in accordance with their culture.

Mothers think that getting pregnant is a normal condition and you do not have to go to the health facility unless you have serious complications like prolonged labor or when you face serious problem during delivery. (IDI-08, Male Healthcare provider)

Mothers also believe in traditional rituals which they believe will help them during delivery and there are also local traditional healers whom they seek care when they feel sick.

There are some traditional rituals that are used or done by the pregnant woman specially when carrying their first child. For instance: in her last trimesters she puts on some body adornment as a protection from all evil which is just a myth. Also, in the last weeks or days of her pregnancy, the mother should not leave her home. It is a belief. (IDI-14, Lactating Mother)

Also, a health-care provider stated some traditional rituals that pregnant mothers perform during the last trimester of their pregnancy term.

There is something called Abayo-abay which a traditional ritual. Instead of visiting a health facility, there are some rituals which mothers perform and believe it will help them during childbirth. They believe it would help them during labour. The pregnant mother would cook and invite other mothers, they would read Quran for her and make prayers to help her ease her labour. Pregnant women prefer calling the village elders to do the rituals instead of going to health facility. (IDI-04, Female, Healthcare provider)

Male Dominance in Decision Making

The society is male dominated society where the husbands control women’s decisions in every aspect including seeking healthcare services. Some of the mothers said that they cannot decide to go to the health facility, the decision belongs to their husbands and it is something that is in their culture.

Male dominates all the decisions in the family. Men controls woman’s personal, social, and economic independencies. This is a social problem; we are aware off as a ministry” (IDI-05, Male, Policy-maker). “We are not fully free to decide where to deliver and where to seek health care. Our husband always gives us the directions on daily basis. We obey our sheikhs (husbands) and we can’t refuse their orders. He is the one who decides whether or not the woman is going to seek healthcare. (FGD-05, Pregnant mother, Deynile)

Childbirth is seen as women’s issue, but men are the ones that are involved in providing resources, decision making and access to health care where most men especially in the IDPs choose cheaper ways by agreeing to TBAs. Men’s decision making and controlling women’s life limits women’s decisions to seek health-care services.

Lack of Family/Husband Support

Women have a huge responsibility for taking care of their kids and household. Unable to leave their homes and lack support from other family members, especially husband.

No, our husbands are either busy and hustle with their daily works or chew Khat. They are absent always. How can he support us? You get support only when you live with your really mother. (FGD-06, Pregnant woman, Kahda)

One husband stated that it is not exciting to involve women issues.

We don’t like to accompany our wives to the health facilities and discuss maternal health issues with our wives and health professionals, we don’t want get involved on women issues. (IDI-17, Husband)

Female policy-maker made clear that, because of the heavy workload for taking care of multiple children, lack of family support and inability to find a babysitter would put pregnant mothers not to attend antenatal cares.

The sick mother sometimes has other children at home and due to lack of family support its difficult for her to find a babysitter so she wouldn’t be able to attend antenatal care or seek medical treatments. (IDI-07, Female, Policy-maker)

Community Level Barriers

Exposure to Armed Conflicts- Security Barriers

Study participants indicated that some locations could be insecure and may limit or halt accessing maternal health services.

Fear of taking health workers to some locations or areas due to security issues, checkpoints and blocked roads could be a challenges/barrier to providing free maternal healthcare for some IDPs. (FGD-04, Male, Camp leader)

Sometimes when the mother is feeling labour pain and she is rushed to the hospital, the roads are blocked, and the police start gunshots. It is too risk even the laboring mother might give birth on the way or she will be returned to her home where she gives birth with the help of traditional birth attendant. (IDI-12, male, camp leader)

In Accessibility of Health Facility

Study participants reported distance as another barrier to accessing maternal health-care services. Mothers complained about long distances and absence of reliable mode of transportation which can help them to reach the health facility. Majority of the mothers choose to give birth at home due to the long distances from the health facility since they can neither go by foot nor pay for transportation cost as one pregnant mother relate her experience:

I prefer giving birth at the MCH, it will be ok for me but, I hesitate to go there. It is far away; I cannot afford it and due to long distance, I cannot even walk to the hospital it takes more an hour for a person to reach there. For instance: I am a sick mother (anemic) I cannot walk all that distance, the MCH is far away from our area and I cannot afford the transportation cost (FGD-07, Pregnant woman, Deynile).

High transportation costs, poor physical accessibilities and lack of free ambulance were listed by the participants. Most of the mothers were unable to reach the health facility easily. Some of the mothers and community health workers attributed lack of accessibility and poor infrastructure as part of the challenges that hinder a woman to attend to the existing health services. A member from the national midwifery association stated that:

Some mothers have difficult to access the health facilities when it is required during the pregnancy or after as she can’t access a car and are unable to go by foot, which could be too late when transport has been found. (IDI-06, Female, Midwife association)

Some mothers live far from the health facilities therefore if she or the child would need urgent health care during the night and can’t access a car and are unable to walk, they would have to wait till the morning to seek treatment. (IDI-03, Female Healthcare provider)

Most of the mothers had both distance and travel challenges when attending maternal and child health services. Distance and monetary constraints and physical road challenges were the main barriers that mothers reported during the interview.

No access to transport when in labor as there are no public transport available during late hours. You know that in this area the MCH is very far away, and to go to the MCH you need fare so if you do not get fare you decide to stay at your home. The long distance is discoursing us to visit the health facilities; its tiring. (FGD-07, Pregnant mother, Dharkenlay)

Since there are no free transportation services, woman and her family have to pay extra money to come back from the health facilities or travel long distances. Participants accounted that there are some disparities among IDP families when it comes to transportation costs.

The other difference is not being able to pay for transportation. The households that are well off usually utilize transportation to reach healthcare facilities, but the poorer households walk to the health facilities because they cannot afford transportation. (IDI-17, Husband)

It is very difficult for me and many other mothers to reach this health facility to seek checkups and give birth at health facility due to distance. I am sick and I can’t go there by foot and comeback by foot. (FGD-06, pregnant woman, Kahda)

Organizational Level Barriers

Lack of Privacy/Pregnancy Secrecy

Lack of privacy at the health facilities was another obstacle which mothers complained about. Sometimes there are more than one patient or more than one health-care provider at the room and it will be difficult for a patient to explain her problem to the health-care provider.

There is no privacy in the clinics, there are other people sitting there and everybody is listening to what you are telling the nurse. There are things you want ask or tell the nurse alone, but you cannot because there are other patients. There are also a lot of gossips in the health facilities. Yes, gossips. I can give you an example: My friend went into labor one time and her mother and I took her to the nearby hospital. When we brought her to the hospital and the girl was in labor pain, the staff just left her in the room and started gossiping about things in their lives. The mother was upset at the way she was neglected so we took her to a different health facility. (FGD-07, Lactating mother, Dharkenlay)

A community health worker also explained:

I have tried to convince a pregnant mother to go and give birth at the health facility, but she told me, she has never visited a health facility. She is suspicious and fears that she will be videotaped/ recorded when she is giving birth and she doesn’t want to go there. (IDI-13, Female, CHW, Deynile)

Mothers also reported that their husbands may force them to deliver at their homes to avoid their wives being exposed in front of the male health workers.

When I give birth at home with the assistance of a traditional birth attendant, I’m covered with clothes and no one is allowed to enter into the room. Your privacy is not compromised when you are giving birth at the health facilities. When you give birth at the hospital you are made to sleep over the coach and the place is open; everybody can see you but when you are giving birth at your home it is only you and the traditional birth attendant. No one else can enter the room. So, because of privacy I prefer giving birth at my home. (FGD-06, Lactating mother, Kahda)

Privacy is key for them, and they believe home delivery is the only place that they feel both safe and secure. Yes, we also believe that TBA is good for them, and we pray for them during delivery and read Quran for them. I would not accept a male nurse in the health facility to deliver my wife because it is not safe. (FGD-04, Male, camp leader, Dharkenlay)

Shortage of Logistic Supplies and Equipment: Poorly Functional Services

Lack of well-equipped clinics for delivery and the absence of necessary medications in some health facilities was another issue which was reported study participants.

The biggest problem mothers are facing is that the MCH only operate during the day, people are overcrowded and the resources available for the people are limited, and the living conditions are very difficult. There are no midwives that are working in this particular health facility, they just have nurses that will ask you only questions. They cannot afford to go to private hospitals because of these challenges they prefer giving birth at home. (FGD-6, Lactating mother, Kahda)

Some mothers complained about long waiting hours in the health facilities and poor functionality of the public health facility around them. Some of them reported that there was limited working hours in the health facilities.

I have paid money to travel to this health facility and I cannot lie, I have not received any help from the staff. They took my number and told me they would call me. I am still waiting for their phone call. I do not understand why I am being mistreated when everyone else here are receiving support and enjoying the services. I am willing and ready to receive support. (FGD-07, lactating mother, Dharkenlay)

Every time I visit the health facilities, I don’t get quality medical care … so it’s better for me to stay and deliver at home instead of killing my precious time and wasting my money. (FGD-07, lactating mother, Dharkenlay)

Previous Negative Experiences with Health Facility

Participants reported previous negative experiences as another obstacle to seeking healthcare services. Mothers also complained about; the information they give to the care providers was not listened to and considered.

I didn’t like the way the place was open the first time I have given birth at the hospital; it was not too good for me. There were other patients, nurses, and midwives in the labor ward so everyone can see you and hear what you are saying. I do not think I will ever go back to that place again; it is better to use at least curtains to cover you. There are many people at the facility …. Sometimes I go there early in the morning and come back in the evening without being assisted while I am tired and exhausted, I do not want even to go back there again and waste my time and money. (FGD-7, Lactating mother, Dharkenlay)

When some mothers come to the health centers with really ill child and they are overemotional they would request some random medications for their child that they think they need, which the doctors would not agree, she would end up going back home with the ill child out of frustration and it could happen that she never returns back there. (IDI-15, Pregnant woman)

The participants also mentioned that, due to the small size of the clinic and the health worker’s behavior at the health facilities it may be difficult to assist all the mothers or patients.

Even when healthcare workers are qualified to do their jobs, some of them might not encourage the women to come and enjoy their services at the health facility. Another thing is due to the small size of the health center it could sometimes be overcrowded and can only fit a small number of patients which could Cause longer waiting time and delays so women will not come back and will have a negative memory, so this discourages them from going to the clinic and they end up giving birth at home. (IDI-04, Female, Healthcare provider)

Service Hours of Health Facilities

Participants reported that the health facilities that are located to IDP nearby locations do not work at night. They indicated that the normal closure of the facilities is 5 pm afternoon.

Unlike the private hospitals in the city, the IDP health centers close earlier which could Cause laboring mothers to deliver at home. Never saw a clinic here that is working at late night. Even other communities have the same concern. All health facilities are closed during Fridays which makes it difficult for the IDP community to seek treatment specially when they can’t afford to go to other hospitals. (FGD-06, pregnant mother, Kahda)

Health facilities in this district don’t work 24 hours. They do not have light in the night even. The close during the evening time and open morning when the people wake up. (FGD-07, Lactating mother, Deynile)

Policy Level Barriers

Challenges for Proper Referral Pathway

As referral system aids comprehensive management of patient’s health needs, study participants stated challenges during the referral of patients from MCH to big hospitals for advanced care. Lack of available free ambulance, delays between appointment time and referral time, costs related to the referrals were the barriers that most of the health seeking mothers stated.

Usually, the IDPs live far from the health centers than the host community which makes it harder for them to walk or to find transport to seek health care, sometimes it could be hard for an IDP mother to reach the main hospital. If our disease cannot be solved in this MCH, that will be the most serious time. we cannot have referrals. No ready ambulance and no networks. (FGD-05, Lactating Mother, Deynile)

Pregnant and Lactating mothers insisted that there is no ideal referral system that can be used. The government or international organizations does not provide a route to follow for the referral. For instance, if a pregnant woman faces obstructed labour and need a referral to tertiary healthcare service, there is no available ambulance or referral connections.

Our referral system is ineffective really. If you want to refer a pregnant mother with obstructed labour, you do not have connections between the homes to MCH or from MCH to big hospitals. This is because of many reasons. Most of the times, mothers refer themselves to the hospital. (FGD-03, Female, CHW, Dharkenlay)

A midwife working in one of the primary health facilities declared that there are no available referral forms to follow up the patients.

When we try to refer pregnant women, we don’t usually issue a referral form. They are not in place. We cannot follow up the doctors that attained to our patients because of there are well established connections between hospitals. Yes, healthcare institution does not work together. Sometimes the IDPs have free health care but with challenges. They face many challenges and this referral for the serious patients is one of them. (FGD-01, Female, Midwife, Deynile)

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to explore and identify barriers to maternal and child health service utilization in internally displaced populations using the McLeroy et al’s Socio-Ecological Model (SEM). This framework was the continuation of the Urie Bronfenbrenner’s famous Ecological systems theory (EST) that highlights the interrelationship of multi-layer interdependent factors in personal, family, community and environment determining human behavior. McLeroy conceptualized the Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model and adapted more specifically as a framework to explore the determinants of health behavior. This socio-ecological model focuses on individual, population, organization, and policy-level determinants of health and interventions. It emphasizes how multiple levels like interpersonal, community, institutional, environmental, and public policy can influence individual behavior and health.

This study analysed the existing barriers that mothers and their children face in accessing maternal and child health services. Access to quality, Basic, and comprehensive health-care services impact every person’s overall physical, emotional, social, mental health status and his/her quality of life, let alone the weak and disproportionate groups in the population like IDPs and marginalized community members. If not attained this access, barriers like unmet health needs, delays in receiving appropriate care including ANC and institutional delivery, inability to get preventive services such as immunization, and preventable hospitalization will emerge.9 The ability to access health-care services depends generally on availability, timeliness, affordability, and convenience.

According to this study finding, barriers contributing to low utilization of maternal and child health services include; individual-level barriers (economic barriers, lack of decision making power of women, TBA trust, poor knowledge and awareness on pregnancy danger signs, and fear of going to unfamiliar areas), interpersonal-level barriers (cultural and traditional beliefs, male dominance in decision making, and lack of family support), community-level barriers (exposure to armed conflicts-security barriers and distance and transportation barriers), organizational-level barriers (lack of privacy in the facility, poor functional services, negative experiences, and closure of the health facility in some hours), and policy-level barriers (lack of proper referral pathways).

To our record, this is the first study to comprehend maternal and child health of internally displaced populations in Somalia. This qualitative paper finds out that different barriers that limit the utilization of maternal and child health service exists in IDP settings. The barriers identified by this paper will help in understanding and exploring why mothers from displaced communities have very low maternal and child health service utilization and how these barriers affect their utilization. The study used Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) for both its literatures and thematic analysis in order to validate the complex nature of maternal and child healthcare access in IDP settings and how these different barriers interconnect and influence on each other.

As identified by Jalu et al in Somali region of Ethiopia, there are multilayer barriers consisting of individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and policy-level barriers that influence or affect the maternal and child health services utilization. This study finding agrees with this study and finds that low household income (individual-level barrier) affects maternal and child health services utilization. This study participants suggested that due to lack of sufficient money for transportation and medicine, most of the mothers do not attend antenatal care, delivery, and post-natal care services. This study comes with a similar conclusion with studies conducted in Ethiopia.9,10

According to the last Somali Demographic and Health Survey (SDHS), only 33% of deliveries are assisted by skilled birth attendants, while the rest of the deliveries take place at homes.3 Lack of decision making power for women that study participants highlighted was similar to the reports by previous researches.11,12 Trust and traditional acceptance are the most cited reasons mothers choose home delivery with the assistance of TBAs.

Conclusion & Recommendations

This study found complex and multifaceted personal, interpersonal, community, organizational and policy barriers that hamper the uptake of maternal and child health service in the IDP community of Mogadishu, Somalia. The reported personal factors that impede maternal and child health service utilization include low socioeconomic status (unemployed and illiterate mothers), lack of health decision making power of women, greater acceptance and trust of traditional birth attendance and comfort of home delivery, and limited knowledge and awareness on the pregnancy danger signs.

The interpersonal and community barriers of maternal and health services utilization found in this study were the existence of cultural and traditional beliefs/practice, male dominance in decision making and lack of family and husband support of pregnant and lactating mothers, as well as insecurity and armed conflict, formidable distance to health facilities and transportation challenges.

The organization and policy obstacles that hurdle mothers to seek and use maternal and child health services were the lack of privacy and female workers at the health facilities, absence of essential medical supplies and equipment in the facilities, and previous negative experiences as well as limited-service hour of the health facility and challenge of providing timely and appropriate referral mechanism to the next level health institution.

Hence, multi-component interventions that target these complex and multifaceted barriers are required to be implemented in order to improve maternal and child health services utilization among IDP in Mogadishu, Somalia. Based on the findings, and the conclusion drawn, this study made the following recommendations:

First, government and its partners should improve the socioeconomic status mothers through creating income generating sources, and advocate for girls’ education and women empowerment, which could subsequently enhance the role of mothers to make decision of when, and where to seek maternal and child health services. It would also have a trickledown effect on the ability pregnant women to afford and access maternal as well as increase the likelihood of mothers to disengage with harmful traditional beliefs/practices.

Second, create demand of maternal and child health services by organizing community mobilization and engagement with all community members with special consideration on women of childbearing age, men, opinion, and gatekeepers to design, and implement with awareness and sensitization interventions about benefits with maternal and child health services, and risk of home delivery, women empowerment, and family and husband support. Future maternal and child health programs should emphasize and have strong component of behavioral change and communication that employ social health marketing principles to design participatory and contextualized health education and awareness campaign.

Third, for mothers to have positive experience at the health facilities, maternal and child health services should be organized and delivered around away that are medically appropriate, maintain privacy and confidentiality, and responsive to the culture, need and preference of pregnant women. Female workers should be greatly enrolled at health facilities and subsequently trained with communication skills so they could establish a good relationship and rapport with mothers attending the health facilities.

Fourth, governments and their partners should invest in health-care infrastructure, most importantly building good roads, and improve the functionality of ambulance services, establishing proper referral mechanisms and addressing costs associated with it, most importantly considering providing return transportation services.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. World Health Organization. Maternal mortality across countries. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality.https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality.

2. Newbrander W, Natiq K, Shahim S, Hamid N, Skena NB. Barriers to appropriate care for mothers and infants during the perinatal period in rural Afghanistan: a qualitative assessment. Glob Public Health. 2014;9(sup1):S93–S109. doi:10.1080/17441692.2013.827735

3. UNFPA. Somali demographic and health survey. Vol. 1. Report; 2020. Available from: https://somalia.unfpa.org/en/publications/somali-health-and-demographic-survey-july-2019-newsletter.

4. Yarnell M. Durable solutions in Somalia: moving from policies to practice for IDPs in Mogadishu report; 2019. Available from: https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports/2019/12/13/durable-solutions-somalia-moving-from-policies-practice-for-idps-mogadishu.

5. Millman M. Access to health care in America; 1993.

6. World Health Organization. Barriers and facilitating factors in access to health services in the Republic of Moldova. Annual Report 2020; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/barriers-and-facilitating-factors-in-access-to-health-services-in-The-republic-of-moldova.

7. Ganle JK, Parker M, Fitzpatrick R, Otupiri E. A qualitative study of health system barriers to accessibility and utilization of maternal and newborn healthcare services in Ghana after user-fee abolition. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):1–17. doi:10.1186/s12884-014-0425-8

8. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

9. Tesfaye G, Chojenta C, Smith R, Loxton D. Delaying factors for maternal health service utilization in eastern Ethiopia: a qualitative exploratory study. Women Birth. 2020;33(3):e216–e226. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2019.04.006

10. Jalu MT, Ahmed A, Hashi A, et al. Exploring barriers to reproductive, maternal, child and neonatal (RMNCH) health-seeking behaviors in Somali region, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0212227. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212227

11. Munguambe K, Boene H, Vidler M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to health care seeking behaviours in pregnancy in rural communities of southern Mozambique. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):83–97. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0141-0

12. Kimani S, Kabiru CW, Muteshi J, et al. Exploring barriers to seeking health care among Kenyan Somali women with female genital mutilation: a qualitative study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2020;20(1):3. doi:10.1186/s12914-020-0222-6

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.