Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Expectation and Complaint: Online Consumer Complaint Behavior in COVID-19 Isolation

Authors Wang W , Zhang Y, Wu H, Zhao J

Received 6 August 2022

Accepted for publication 14 September 2022

Published 4 October 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 2879—2896

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S384021

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Weihua Wang, Yuting Zhang, Huaming Wu, Junjie Zhao

School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Benbu, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Weihua Wang, School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Bengbu City, 233000, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86-552-3171001, Fax +86-552-3175978, Email [email protected]

Purpose: This study aims to articulate the nature of consumer complaining behavior (CCB) by analyzing the mechanism and characteristics of online CCB in COVID-19 isolated environment.

Patients and Methods: For the purpose, this study collected data via a web-based questionnaire survey from 408 consumers in Shanghai, China during COVID-19 isolation. Through building and analyzing a structural equation model that consists of six latent variables such as perceived service quality, perceived product quality, customer satisfaction, negative emotion, customer complaint; the study analyzed the basic characteristics of CCB, and focused on the moderation test of consumer expectation to validate its important role in consumer decision-making behavior.

Results: First, compared to perceived service quality, perceived product quality has a stronger influence on customer satisfaction and has a weaker influence on negative emotions in the COVID-19 isolated environment. Second, the total influence of perceived product quality on customer complaints is stronger than that of perceived service quality. Third, the direct impact of negative emotions on customer complaints was much stronger than the effect of customer satisfaction on customer complaints. Meanwhile, it can also act as a mediating variable to make customer satisfaction have an additional indirect effect on complaints. Finally, the study also found that consumer expectation can reinforce the influences of customer satisfaction on negative emotions and customer complaints, while it weakens the effect of negative emotions on customer complaints.

Conclusion: This study suggests that the classic CCB factors still exert a stable influence on customer complaints through cognitive and emotional response pathways, but the influence difference is obvious in the COVID-19 isolated environment. And the influence processes are significantly moderated by consumer expectation level. Enterprises should conduct more targeted marketing interactions, according to these CCB characteristics.

Keywords: perceived service quality, perceived product quality, customer satisfaction, negative emotion, customer complaint, consumer expectation

Introduction

In March 2022, COVID-19 broke out in Shanghai, China’s commercial capital. On 28 March, an isolation strategy was implemented; people were asked to suspend public social activities, stay inside and observe home quarantine, and shop online to meet the needs of their daily existence. That is a necessary and effective measure for the prevention of infection, but it puts every person in a relatively enclosed ambience.1 This brings great inconvenience to people’s lives, and it also provides a quasi-experimental opportunity for market researchers to observe the behavioral details of consumers. The small behavioral details in extreme environments often reflect some essentials of consumer behavior.2 Thus, every slight change of consumer behavior in this environment has special significance for related research. For example, the changing characteristics of CCB will be discussed in this study.

Numerous studies have shown that COVID-19 has increased the prevalence of negative psychological effects.1,3,4 This affects individual and social behaviors widely, notably in the fields of public health,4,5 social contact,6 and marketing.7–10 Complaining is the concrete reflection of human negative psychological factors.11 CCB is bound to be influenced by negative psychological effects on consumers.12–14 Against this background, it is necessary to comprehensively investigate the key factors that influence CCB in this environment.

First, this study emphasized the specific target of online shopping: products and services. Consumers’ perception and evaluation of these two factors constitute the basic content of consumer complaints.15 Under normal conditions, researchers are more concerned about the influence of service factors on CCB,16–18 because service marketing has been dominant in the current market environment.19 However, getting products is back a priority in COVID-19 isolation. This is the basic living security of consumers. In this context, whether product factors or service factors have a greater influence on consumer complaints needs further analysis. Secondly, satisfaction and negative emotional factors are also the key to solving problems.14,20,21 The former represents the overall cognition and positive evaluation level of consumers in the transaction process;21 The latter symbolizes consumers’ negative emotional reaction to a bad trading experience.18,22 As the classic factors affecting CCB, their existing role under the influence of COVID-19-induced negative psychological needs to be reconfirmed.

The above factors constitute the most basic CCB influence system and are often discussed in the related discussion on CCB; the effects arising from the interdependence of these factors show the behavioral characteristics of CCB in a general market environment. However, it should be noted that the existing market environment has changed greatly in COVID-19 isolation.7–9 The most significant feature is COVID-19-induced social disconnection.7,8,23 All offline business activities have stalled as a result of the epidemic. Average consumers are forced to shift all their attention to online shopping. This is bound to affect their online shopping expectations. This study attempts to focus on the issue. Because consumer expectations are the source of all buying behavior, in a free market environment.24 All consumers start buying based on some kind of rational or emotional expectation, and the target of expectation is usually a product, service or a combination of the two.25 Without expectations, there would be no disappointment or dissatisfaction; and complaints would never arise. Expectations are closely related to complaints.26 So, can the changes in consumer expectations lead to changes in CCB during COVID-19 isolation? If so, what are the characteristics of this change? Can it reflect the nature of CCB more deeply? These are thought-provoking questions for both psychology and marketing researchers.

To answer the above question, this study provided an overview of perceived service quality, perceived product quality, customer satisfaction, negative emotion, customer complaint and consumer expectation, as well as a review of key literature and a development of hypotheses. Then, the study established a CCB model including the above factors based on stimulus-organism-response (SOR) theory, and relied on the online consumer survey data during the quarantine period in Shanghai for analysis. The results provided the answer to the question “How can consumer expectations shape CCB in the post-COVID-19 era”. This can not only help researchers prepare for similar studies in future, but also assist related enterprises in developing more targeted complaint-handling strategies.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Perceived Product Quality and Perceived Service Quality

Perceived quality has been defined as the consumer’s judgment about the all excellence or superiority of a “product”, which can be a specific product, service or product-service portfolio.27 In the process of online shopping, the perception of products and services is the basic of the consumer’s shopping experience.2,20 Thus, the specific discussion of these two perceived factors is carried out by the perceived product quality and perceived service quality, which are also the two exogenous variables and represent the “S” (stimulus) in this study of CCB.

Specific to perceived product quality, there is a long-standing tendency in some marketing research to focus on the discussion of customer benefits of a product.27,28 These studies suggest that bundles of product attributes collectively represent a certain level of quality, which thus provides utility to consumers.27,29 The benefits are judged by the perceived quality level, a bundle of attributes compared to consumer expectations.28 According to this view, perceived product quality is defined as the gap between customers’ perceived level and expectations of product quality.27 And on that basis, scholars further concluded quality as a form of overall assessment of a product; and argued that quality is a comparatively global value judgment.30 These types of assessments or judgments are commonly based on long-term transactions between consumers and enterprises,27 which can reflect the quality level of products provided by enterprises from the perspective of consumers;28 influence on consumer buying behavior,30 and are closely related to some typical negative consumer behavior.28,29,31 Consider the diversity of online products, this research comprehensively evaluates the quality level of online shopping products from three aspects of comparative quality, actual quality and overall quality to compare and discuss it with service quality, in order to explore the possible deep rules.

Perceived service quality is also a very important concept in the field of marketing. Consistent with the logic of the above definition on perceived product quality. It is generally considered to be the difference between consumer expectations of the service to be received and their assessment of the service actually received; or is the customer’s judgment about the level of excellence or superior of service.32–34 It is also one of the cognitive variables in appraisal processes of purchase behavior.34,35 Thus, the perceived service quality discussed in this study can be defined as the degree to which the service meets the customer’s expectations in the online shopping process.36 High-quality services can attract and retain consumers and strengthen the profitability and market competitiveness of enterprises.34 This is especially important for online retailers because there are significant differences between online marketing and traditional marketing, such as perceived risk, perceived convenience and shopping experience.37,38 Online retailers can only make up for the shortage of online shopping through services to improve consumers’ shopping experience. Therefore, as an important marketing concept, online service quality has attracted widespread attention in related fields.37,39,40 It has become a fundamental topic in the discussion of online customer satisfaction.2,20,40 Especially during COVID-19 induced isolation, consumers only rely on the services provided by online retailers to complete shopping; service quality has a deeper impact on consumer behavior and should be taken seriously.

Nevertheless, Online service quality is a fuzzy concept, notably in quantitative research.37 Previous scholars have done in-depth research on this issue and tried to measure it accurately. For example, some studies have shown that online service quality is mainly composed of seven dimensions: contact, reliability, compensation, responsiveness, privacy, fulfillment and efficiency.36 Another study found that incentive, reliability, security, efficiency, communication and support are the six main components of online service quality.39 Additionally, Cristobal et al concluded that online service quality includes two categories: website design and online retailing services.41 This study focuses on the perceived quality of service, which places more emphasis on the comprehensive quality of the above two categories. Based on previous research, the overall measurement is carried out from three items: staff service quality, information system service quality, and overall service quality.

Customer Satisfaction and Negative Emotion

In this study, customer satisfaction and negative emotion are the subjects of discussion of the “O” (organism), which focuses on the internal processes of CCB. At the same time, they also represent the two different forms of individual processing of the above stimulus information during the generation of CCB behavior. The former represents an individual’s basic cognitive outcomes of stimulus; the latter represents the individual’s affective reaction to the same stimulus. Therefore, they can be considered different aspects of expression on the same consumption experience; namely, cognitive experience and emotional experience.

Customer satisfaction is considered to be the level of satisfying consumer needs after purchase.42,43 This is the key to measuring whether companies are fulfilling their marketing concepts.44 In previous research, cognitive or affective paradigms have been used to predict it. Customer satisfaction under the cognitive paradigm is defined as a function of a comparison between expectations and performance.43,45 This study pays more attention to the cognitive attributes of customer satisfaction. This typical attribute of customer satisfaction increases over time;44 represents the objective and stable consumer attitude that decides marketing strategy success or failure.45

For marketing researchers, attention to customer satisfaction is essential.42–44 Because it is one of the most important issues concerning business organizations of all types, it is justified by the customer-orientation philosophy and the main principles of continuous improvement of modern enterprises.44 For retailers, customer satisfaction is a key indicator of their success in selling products.42 For service providers, customer satisfaction is their eternal main pursuit.2 Because it can reflect customers’ basic estimate of service, it helps enterprises improve service quality and reduce customer complaints.20 For online retail sites, customer satisfaction refers to the recognition of the combination of products and services it provides; it is the foundation of long-term profitability of enterprises.46

The perceived quality discussed in this study is primarily for online shopping quality, which is defined as “the outcome of consumer perceptions of online convenience, merchandise, site design, and financial security”.47 It represents the relevant factors through which online retailers try to satisfy consumers, such as service, physical characteristics, employees, merchandise and even other shoppers.48 Whether it is a small retail site or a large online shopping platform with multiple retail tenants, providing an adequate mix of services and products can increase customer satisfaction. Therefore, the satisfaction of online shoppers depends directly on the quality of the products and services provided by retail websites. This study attempts to compare the effects of products and services on customer satisfaction (consumers’ cognitive experience) in COVID-19 isolation. In view of this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1: The perceived product quality has a positive impact on customer satisfaction. H2: The perceived service quality has a positive impact on customer satisfaction.

In the concept of psychology, emotions are generally defined as a state of mind and body produced after an individual is stimulated; and represent the individual’s affective reaction to the stimulus.49 Introduced in the field of marketing, this concept is defined as the specific combination of emotions caused by consumer experience of service or product;50,51 symbolizes affective feedback on the trading experience.52 Studies have shown that emotions have a strong and compelling influence on consumer behavior.49 Emotions impact information processing, influence reactions, stimulate goal setting, goal-directed behavior of consumers.49,53 Negative emotions towards a company can translate directly into actions against it, such as complaints and even long-term negative word of mouth.50,54 They are elicited by consumers during the decision-making process through service/product related stimuli.54 But, different from the cognitive process of forming customer satisfaction; while emotions are directly influenced by the stimulation (eg, product/service quality), they are also disturbed by cognitive outcomes (eg, customer satisfaction) of the same stimulus. This influenced process of cognitive outcome on emotional response is consistent with the basic proposition of cognitive emotion theory, which suggests cognitive aspects are a precursor of emotional aspects that ultimately lead towards specific actions.55 Such behavioral logic also conforms to the mechanism of CCB occurrence under emotion dominance.14

In light of these studies, we suppose that negative emotions (emotional experience) are influenced not only by perceived product/service quality but also by customer satisfaction (cognitive experience) in COVID-19 isolation, and establish the following hypotheses:

H3: The perceived product quality has a positive impact on negative emotions. H4: The perceived service quality has a positive impact on negative emotions. H5: Customer satisfaction has a negative impact on negative emotions.

Customer Complaint

Customer complaints represent the final “response” to the above cognitive/emotional experience, as the only dependent variable in this CCB discussion. As a kind of post-purchase behavior,56 conventional customer complaints can be simply considered an expression of dissatisfaction with a customer’s behalf to a responsible party;57 it can be an expression of dissatisfaction with a product or service, either orally or in writing, from an internal or external customer.56 Fornell and Westbrook (1984) believe customer complaint is a means of making one’s feelings known when disappointment with a product/service arises.58 Kowalski also defines complaining as “an expression of dissatisfaction to vent emotions or achieve intrapsychic goals, interpersonal goals, or both.”59 In this way, the CCB are closely related to dissatisfaction and negative emotions from the beginning of the complaint problem in the field of marketing research. According to this thinking, some scholars prefer to approach CCB from a cognitive perspective, and contend that complaints were produced by the cognitive appraisal of negative consumption experience.57,60,61 But, other scholars argue that complaint behavior was the result of negative emotions; its source might not be the judgment of dissatisfaction itself, but rather the antecedent negative emotional state produced by the appraisal of unfavourable consumption outcomes.14,62,63 Some scholars even further contend that negative critical incidents can provoke negative emotions, which can ultimately lead to complaint behavior.64 Up to now, the CCB theoretical system is being perfected, but the above debate still exists in the field of marketing.

Moreover, this study focuses on the CCB caused by online shopping in COVID-19 isolated environments; which appears in the form of online CCB. It is defined as an expression of discontent on a customer’s behalf with an online enterprise through the internet.65 It has greater negative effects such as faster transmission, wider reach, and even greater secrecy (eg, private complaint); compared with conventional complaints.65–67 There is also a bright side, in an online environment, all kinds of complaint systems (eg, websites, blogs and APP) also provide many chances for traders to monitor the complaints of online customers, and respond swiftly and suitably.67 It is a good information strategy underpinned by the internet and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, and it allows online traders to incorporate customers into more personalized and intelligent interactive relationships; online complaints can be the reflection of human-computer interactivity, which is advantageous for both buyers and sellers. But, in this context, people need to refocus on that old problem, how do cognition and emotion affect CCB? Because the occurrence mode of the CCB directly determines the design process of the complaint handling system and the distribution of service resources.68 After all, problems arising from rational cognition can be handled automatically by AI systems, while emotional problems can only be solved by humans ourselves.

Meanwhile, it is also helpful for researchers to have a deeper understanding of the essential characteristics of CCB in COVID-19 isolated environments by discussing the mechanism of CCB through cognitive and emotional models. For this reason, this study comprehensively compares the influence process of customer satisfaction and negative emotions on CCB and sets up the following hypotheses:

H6: Negative emotions have a positive impact on customer complaints. H7: Customer satisfaction has a negative impact on customer complaints.

In addition, on the basis of the above discussion, we speculate that some underlying mechanisms exist between perceived quality (stimulus) and customer complaint (response) via different consumption experience (organism). This study developed the following hypotheses:

H1a: Customer satisfaction plays a mediating role in the relationship between perceived product quality and customer complaints. H2a: Customer satisfaction plays a mediating role in the relationship between perceived service quality and customer complaints. H3a: Negative emotions play a mediating role in the relationship between perceived product quality and customer complaints. H4a: Negative emotions play a mediating role in the relationship between perceived service quality and customer complaints. H5a: Negative emotions play a mediating role in the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer complaints.

Consumer Expectation

Consumer expectation is a classical marketing concept. It was defined perfectly and reasonably from various approaches according to different theoretical foundations many years ago. In the earlier expectation-confirmation theory (ECT) researches, consumer expectation is often regarded as a kind of pre-consumption belief.69,70 It is a prediction made by customers concerning what they believe will be the outcome of a service transaction or product exchange before the purchase.45,71 But, ECT ignores potential changes in consumers’ expectations following their consumption experience and the impact of these changes on subsequent cognitive processes. In the actual research process, the pre-consumption beliefs of consumers are often disturbed by their consumption experience, and difficult to measure.71 Expectation confirmation model (ECM) research puts forward the concept of post-purchase expectation, which refers to the total perceived benefits of consumer expects from a product or service after the purchase, and concludes that consumers can continually adjust their expectations as they acquire new shopping information or consumption experience.72 Thus, consumer expectation is also viewed as a dynamic representation of the perceived usefulness of consumption.69

Because of the difficulty of conducting longitudinal studies, the concept of pre-purchase expectation is often difficult to measure.71 The definition of post-purchase expectation is widely used. With reference to the core idea of this definition, the consumer expectation in this study refers to the total perceived benefits an online consumer expects from a product and service after the purchase. It’s generally believed that If the actual experience customers have with a deal exceeds their expectations, they are usually satisfied. If the actual performance falls below expectations, they are typically disappointed, even complain.65 Consequently, reasonable expectations are a key factor that affects the shopping experience of customers.

Previous scholars have given full and particular research on the origin of consumer expectations, and found that customers weigh their purchase decisions through collecting information from advertising, salespersons, word-of-mouth, or even testing products.69,70 This information influences consumer expectations and gives them the ability to evaluate the quality of the product or service to meet their decision-making needs. This shows that the occurrence process of consumer expectation has a typical social cognitive orientation. For another, consumer expectations reflect past and current consumption evaluations.72 It is driven by the existing consumption experience, which comprises not only cognitive experience but also emotional experience.73 This means that consumer expectations are closely related to customer satisfaction and negative emotions.74

Consumer expectation forms the baseline for consumers to evaluate every deal, and broadly influences consumer behavior at every stage.72 However, previous studies have mostly focused on the role of consumer expectations in the early stage of consumer behavior.70,71,75 These studies delve into the direct impact of consumer expectations on the consumption experience. Insufficient attention is paid to the transformation process and subsequent influence process between different consumption experiences. In this study, given its close association with the relevant factors of CCB, it is likely to have an impact on the relationships between customer satisfaction (cognitive experience), negative emotions (emotional experience) and customer complaints. So this research chose it as the moderator variable to dissect its potential impact on the late stage of CCB.

First, customers with high expectations pay more attention to transactions, and become more emotionally involved. Their dissatisfaction with not gaining the desired shopping experience means greater emotional loss, and is more likely to induce negative emotions. This also implies that consumer expectations can promote the transformation from cognitive experience to emotional experience. To confirm the above speculation, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H5b: Consumer expectations positively moderate the influence of customer satisfaction on negative emotions;

In addition, different consumer expectations are driven by the consumption experience before consumption,76 and this difference affects the subsequent experience and decision.73 For online consumers, high-expectations are based on better and richer prior shopping experience, which is sufficient cognitive process material. Therefore, the consumption experience of high-expectation consumers can be closer to a cognitive result, and their complaints are more influenced by customer satisfaction (cognitive experience). Compared to high-expectation consumers, low-expectation consumers’ consumption experiences depend more on their own emotional reactions because they lack sufficient information for cognitive judgment. Thus, their complaints were also more influenced by negative emotions (emotional experience). To confirm the above speculation, the following hypotheses are developed.

H6b: Consumer expectations negatively moderate the influence of negative emotions on customer complaints. H7b: Consumer expectations positively moderate the influence of customer satisfaction on customer complaints.

Research Design

Conceptual Model

As shown in Figure 1, based on the relevant literature, this study establishes a comprehensive framework to verify these relationships between perceived product quality, perceived service quality, negative emotions, customer satisfaction, customer complaints and consumer expectations in COVID-19 isolation. The SOR theory was used as the theoretical basis for this framework. The “stimulus” (S) includes the perceived service quality and perceived product quality. Customer satisfaction and negative emotion as two aspects of expression on consumption experience belong to the issue of “organism” (O), customer complaint is represented as the final “reaction” (R).

|

Figure 1 Conceptual model and hypothesis. |

Survey Samples

The reliability and validity of the instrument were tested through a two-step process. First, this study performed a pre-test to ensure the validity and reliability of the survey. The pre-test was conducted with 35 respondents, including 30 marketing students and 5 experts, who were asked to comment on the wording and relevance of the questionnaire and to make appropriate corrections. Pre-test results were tested via confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach’s reliability. Two items of perceived service quality, one item of customer satisfaction, three items of negative emotion, and one item of consumer expectation were erased. The formal questionnaire consists of 18 concept measurement items and 4 demographic questions, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. In addition, to reduce common method bias and optimize the design of the survey, this questionnaire added some necessary psychological and temporal separation when measuring correlated variables; eliminated ambiguity in meaning items. In addition, this survey objective is to measure the correlated variables of CCB. It is best to distinguish qualified respondents with failed online shopping experience. This study refers to Wu’s method, asking participants to reflect on a recent negative experience in online shopping (within the past 1 week).76 The main purpose of this tactic is to define a clear memory for the respondents, which serves as the basis for completion of the survey.

|

Table 1 Measurement Instruments |

|

Table 2 Demographic Description of Sample |

In the second stage, an extensive questionnaire survey was completed. The main survey data was collected among the users of JD.com in the middle of April, 2022, during the strictest quarantine period in Shanghai. To find the target group, the study obtained a convenience sample in Shanghai city via a web-based smart survey. In total, 476 registered users of JD.com participated in the survey. With the exclusion of 68 invalid questionnaires, a total of 408 complete and valid questionnaires were used for data analysis.

Ethics Statement

The above data was volunteered by the participants. Following the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), this survey ensured the confidentiality and anonymity of participants, and was approved by the School of Business Administration of Anhui University of Finance and Economics.

Constructs Measures

Based on previous research, the measurement items were modified moderately to fit the target group. Participants were asked to respond using a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement. As shown in Table 1; this study uses three items to measure the following variables: perceived service quality, perceived product quality, customer satisfaction, negative emotions, customer complaints and consumer expectations.

Sample Description

The demographic profile of the participants is presented in Table 2; 217 participants are female (53.2%), while 191 are male (46.8%). The majority of respondents are younger than 40 (76.6%) and 228 respondents (55.9%) hold a college or university degree, while 32 respondents (7.9%) hold advanced degrees, and 278 respondents (68.1%) earn 5000 to 15,000 Yun a month.

Data Analyses

Data collected for this research was analyzed using smartPLS 3.3 to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement. PLS can simultaneously estimate the measurement and structural models, prevent inadmissible solutions and factor indeterminacy. It is suitable for testing complicated relationships.

Reliability and Convergent Validity

This survey estimated the reliability and convergent validity of the factors through AVE (average variance extracted) and CR (composite reliability). As shown in Table 3, the AVE values for all latent variables were all above 0.50, and the CR values were above 0.70; which indicates that hypothesized variables can account for more than half of the variances observed in the items.2 Meanwhile, Cronbach’s alpha for the model’s constructs was higher than 0.7, which also supports that the items within each variable exhibited high internal consistency and high reproducibility of the findings. In addition, factor loading greater than 0.50 is considered to be convergent validity is good. In this measurement model, all factor loads of the items ranged from 0.825 to 0.933. This means that the reliability and convergent validity of all constructs can be guaranteed.

|

Table 3 Test Results of Internal Reliability and Convergent Validity |

Common Method Bias Test

In this study, potential biases resulting from common-method variance may occur since self-reported data was used. According to Harman’s single-factor test, which is the most general approach to the problem of common method bias;2 this study found that cumulative extraction sums of squared loadings of the only factor is 34%, which means that the common method bias is not significant.

Discriminant Validity of Constructs

This study checked the discriminant validity by calculating correlations between constructs. The results show that the square root of the AVE values of each factor is larger than its correlations with other factors. These are shown in Table 4, which confirms discriminant validity.

|

Table 4 Correlations (Squared Correlations), Reliability, and AVE |

Structural Model Results

This study began by checking the collinearity issues in the structural model, and identified that all variance inflation factor (VIF) values fell below the 5.00 threshold level, demonstrating that collinearity did not affect the structural model. Meanwhile, SmartPLS presents the R2 of each dependent variable. The R2 of NE is 0.401, indicating that the variation that can be explained is 40.1%. The R2 of CS is 0.371, indicating that the variation that can be explained is 37.1%. The R2 of CC is 0.548, indicating that the variation that can be explained is 54.8%. These findings suggest that the explanatory power of structural model were satisfactory.

PLS algorithm analysis results show that the path coefficient between perceived product quality and customer satisfaction is positively significant. Meanwhile, a bootstrapping procedure was used to reconfirm the significance of the path coefficient. As Table 5 shows, the path coefficient, significance level, p-value, t-value, and the corresponding 95% bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap confidence interval; this direct effect (β=0.390; p<0.001) is suggested to be significant. Thereby supporting hypothesis H1. Similarly, hypothesis H2~H7 are supported. All direct effects were significant in this study.

|

Table 5 Effect Coefficient and Hypothesis Testing |

Table 5 reveals that perceived product quality has a relatively significant indirect effect (β=−0.046, p<0.001) on customer complaints via customer satisfaction, Hypothesis H1a is supported. Similarly, hypothesis H1a~H5a are supported. All of the mediation effects were significant in this study.

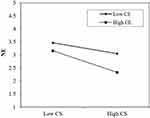

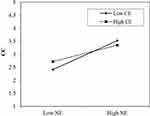

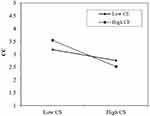

Hypotheses H5b, H6b and H7b propose the moderating effects of consumer expectations on the relationships between negative emotions, customer satisfaction, and customer complaints. The results in Table 5 show that the interaction between consumer expectations and customer satisfaction has a significant effect (β=−102, p=0.037) on negative emotions. This result means that consumer expectations positively moderate the influence of CS on negative emotions. Namely, as shown in Figure 2, high-expectation customer’s satisfaction has a stronger influence on negative emotions. Thus, hypotheses H5b is supported. Similarly, consumer expectations negatively moderate the influence of negative emotions on customer complaints. As shown in Figure 3, Low-expectation customer’s negative emotions have a stronger influence on complaints; hypotheses H6b is supported. Consumer expectation positively moderates the influence of customer satisfaction on customer complaints. As shown in Figure 4, High-expectation customer’s satisfaction has a stronger influence on complaints; supporting Hypothesis H7b.

|

Figure 2 Moderating effect of consumer expectation (CE) between customer satisfaction (CS) and negative emotion (NE). |

|

Figure 3 Moderating effect of consumer expectation (CE) Between negative emotion (NE) and customer complaint (CC). |

|

Figure 4 Moderating effect of consumer expectation (CE) between customer satisfaction (CS) and customer complaint (CC). |

In addition, given the potential relationships between variables. Comparing the total effects of perceived product quality and perceived service quality on customer complaints can help researchers further understand the underlying mechanisms of CCB, especially in isolated environments. As shown in Table 5, compared with the total effect (β= −0.281, p<0.001) of perceived product quality on customer complaint the total effect (β=−0.239, p<0.001) of perceived product quality on customer complaint is slightly weaker. Similarly, the results of comparing the total effects of customer satisfaction and negative emotion on customer complaint are also showed in Table 5, compared with the total effect (β=−0.550, p<0.001) of customer satisfaction on customer complaint the total effect (β=0.459, p<0.001) of negative emotion on customer complaint is weaker.

Discussion

This study explores the basic occurrence mechanism of online CCB in COVID-19 isolation environment; and examines the moderating effects of customer expectations on this mechanism. The structural equation modeling method is adopted to examine theoretical hypotheses. The test results show that the classic CCB factors still exert a stable influence on customer complaints through cognitive and emotional response pathways in an isolated environment. And the influence processes are significantly moderated by consumer expectation level. Specifically, both perceived service quality and perceived product quality can not only promote the occurrence of customer complaints through negative emotions, but also restrain customer complaints through increasing customer satisfaction. These results echo the findings of recent research that focused on CCB in the general market environment. For example, by investigating online shoppers in developing nations, Wattoo et al found that service quality is positively associated with customer satisfaction, which leads to a reduction in customer complaints in an e-commerce context.20 Depending on the results of in-depth interviews and questionnaire survey, Ravichandran and Deng found that frustration emotion is the best predictor for CCB toward the service provider.65 The measure of this emotion is also reflected in this study. In addition, Zhan et al also confirmed that the affective attachment of exhibition customers has a negative impact on complaints through satisfaction.21 These studies generally agree that negative emotions and customer satisfaction have important effects on customer complaints. However, there is no systematic comparison of these effects. In particular, the discussion process from both cognitive and emotional perspectives is lacking, which makes relevant conclusions have a certain degree of one-sidedness. In view of this situation, through a comprehensive comparison of these two factors, this study found that the direct impact of negative emotions on customer complaints was much stronger than the effect of customer satisfaction on customer complaints. Meanwhile, it can also act as a mediating variable to make customer satisfaction have an additional indirect effect on complaints. This result highlights the power of negative emotions on customer complaints, which means that negative emotions play an indispensable role in the occurrence mechanism of CCB. On the other hand, although the direct impact of customer satisfaction on customer complaints is slightly weaker; but it can influence customer complaints indirectly through negative emotions; and its total influence on customer complaints is even greater than the total influence of negative emotions. This means that CCB seems to be more of a cognitive-oriented behavior in the COVID-19 isolation environment.

In addition, recent studies have largely focused on service factors leading to CCB, while ignoring the essential role of product factors. In view of the pressing demand of consumers for online goods themselves in an isolation environment, this study looked at both factors and found that perceived product quality has more influence than perceived service quality on customer satisfaction. For negative emotions, the comparison of influence is reversed. This means that consumers’ cognitive experience is more dependent on the product; emotional experiences are more service-dependent. More importantly, this study discovered that the total effect of perceived product quality on customer complaints is stronger than that of perceived service quality. This result not only implies the characteristics of CCB in the COVID-19 isolation environment, but also reflects the nature of CCB in the context of retail to a certain extent. It is conceivable that the product itself will always be an essential element of retail transaction, and its influence will only be obscured, not extinguished.

Finally, this study confirmed that consumer expectation still plays an important role in the formative process of consumption experience and consumer decisions in the COVID-19 isolation environment. This is consistent with those of previous studies. For example, expectation-confirmation theory suggests that the combination of expectation and performance determines the consumption experience.70,72 Fu et al found that consumer expectation shaped consumer satisfaction through the expectation-confirmation process, and decided on the selection of products.74 The research of Hsieh and Yua further show that consumer expectations can influence the final decision of consumers, through specific consumption experiences, including consumers’ mental cognition and emotional status.75 However, this study is different from previous studies that have focused on the impact of consumer expectations as antecedents of consumption experience. This study focuses on the analysis of how consumer expectations moderate the relationships between different consumption experiences and final responses. The findings of this study indicate that consumer expectation can reinforce the influences of customer satisfaction on negative emotions and customer complaints, while it weakens the effect of negative emotions on customer complaints. To be specific, high-expectation customer’s satisfaction has stronger influences on their negative emotions and complaints; low-expectation customers’ negative emotions have a stronger influence on their complaints. It can be simply considered that the dissatisfaction of high-expectation customers is more likely to turn into negative emotions or complaints; and the complaints of low-expectation customers are more emotional.

Theoretical Significance of Research Results

This study generates several significant theoretical contributions. First, this study relies on SOR theory to propose a behavioral model consisting of basic CCB-related factors, and verified the stability and explanatory power of the model through testing the data in a COVID-19 isolation environment. This model can present the complex relationship between CCB-related factors in a more comprehensive way, so as to compare the influence of similar attribute factors. Based on this model, this study affirmed the important role of product factors in the formation mechanism of CCB, made a comparison with the influence characteristics of service factors, and answered the fundamental question about the target of customer complaints in the COVID-19 isolation environment.

Second, this study reinterprets the occurrence process of CCB from a double perspective of cognitive and emotional. Based on this perspective, this research makes an in-depth analysis of the influence process among perceived quality, consumer experience and customer complaint; and discovers that there are significant differences in the effect of different perceived quality on customer complaint through different consumer experiences. Moreover, comparing the effects of cognitive and emotional proxies (ie customer satisfaction, negative emotion), this study found that the CCB in the COVID-19 isolation environment is a cognitive-oriented decision-making behavior. Such findings are a useful complement to some of the emotion-focused CCB research, and provide a new perspective on investigating consumer behavior in a complex environment.

Thirdly, this study reexamines the role of consumer expectations in consumer decision-making behavior. Most extant studies contribute to theory by analyzing consumer expectations as antecedents of consumption experiences within diverse application contexts. This study found that consumer expectation can promote the transformation of cognitive experience to emotional experience, and has significant influences on the transformation of cognitive experience and emotional experience to final response (customer complaint). Such findings confirm the lasting impact of customer expectations after the consumption experience is formed, expand the scope of research on consumer expectations to provide theoretical material for CCB research and even broader consumer behavior research.

Practical Implications

For online retail enterprises, this study provides useful information regarding the basic mechanism of CCB in the COVID-19 isolation environment. Consistent with the general market environment, product quality and service quality are still the basic source of consumer complaints in COVID-19 isolation. In order to optimize the consumption experience and reduce the negative impact of consumer complaints, online retailers should fundamentally control these two aspects in advance. It should be noted that product factors have become the first cause of complaints in this environment. Companies should put more effort into this to curb consumer complaints. This scenario also reflects the nature of the online retail market, which is that the product is the eternal pursuit of all consumers. Especially in the context of COVID-19 isolation, providing quality products to consumers is a top priority for retailers.

Second, online retail enterprises should pay attention to the influencing characteristics and mechanisms of two different consumption experiences, customer satisfaction and negative emotions. The results of this study show that as a representative of cognitive experience, the former is more affected by product factors. As a symbol of emotional experience, the latter is more dependent on service quality, and has a stronger direct influence on consumer complaints than the former. Therefore, in marketing practice, enterprises should be more targeted to optimize consumers’ shopping experience. For example, consumers’ negative emotions can be improved through more humane services. Through more practical measures (eg, discounts, giveaways) to make up for the lack of product cognitive experience, improve customer satisfaction; thus effectively restraining the occurrence of customer complaints. Such measures are not only effective in COVID-19 isolation, but also have positive effects in the general market environment.

Third, investigating and guiding consumer expectations has always been the focus of corporate marketing activities. For example, through various advertising to enhance consumers’ expectations, strengthen their purchase intentions. However, unreasonable expectations can also lead to increased customer complaints. This study provides an in-depth analysis of the potential impact of customer expectations in the process of customer complaints caused by different consumer experiences; could serve as a part of the scientific basis for establishing guiding mechanisms of consumer expectation.

Limitations and Further Research

Several limitations are acknowledged in this study. First, the study was reliant on self-reported emotions, which led to some instability in related concepts. Future studies will use experiment-based data for reconfirmation to explore deeper details of CCB and improve the universality of the results. Second, in this study, common dimensions of service quality are incorporated as a whole, while the influence of each dimension on customer satisfaction and negative emotions has not been observed. However, different dimensions of service quality may differ according to different consumption experiences. Hence, the influence of different dimensions of service quality should be investigated in subsequent studies. Finally, the data in this study were limited to a single country and region (China, Shanghai) sample in the COVID-19 isolation environment. Other social environments have different cultures, resulting in different patterns of consumer behavior. Thus, subsequent studies will replicate this study in different social environments to extend the validity of these findings.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the School of Business Administration, Anhui University of Finance and Economics. This study was completed with the full knowledge of all participants. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to all the participants.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Fund of AUFE (Grant No. ACKYC21044), and the Innovation Fund of Anhui Province (Grant No. 2019LCX025).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

2. Wang W, Kim S. Lady first? The gender difference in the influence of service quality on online consumer behavior. Nankai Bus Rev Int. 2019;10:408–428. doi:10.1108/NBRI-07-2017-0039

3. Matias T, Dominski FH, Marks DF. Human needs in COVID-19 isolation. J Health Psychol. 2020;25:871–882. doi:10.1177/1359105320925149

4. Boyraz G, Legros DN, Tigershtrom A. COVID-19 and traumatic stress: the role of perceived vulnerability, COVID-19-related worries, and social isolation. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;76:102307. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102307

5. Özen G, Koç H, Aksoy C. Health anxiety status of elite athletes in COVID-19 social isolation period. Bratislava Med j. 2020;121:888–893. doi:10.4149/BLL_2020_146

6. Saltzman LY, Hansel TC, Bordnick PS. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:55–57. doi:10.1037/tra0000703

7. Trzebiński W, Baran R, Marciniak B. Did the COVID-19 pandemic make consumers shop alone? The role of emotions and interdependent self-construal. Sustainability. 2021;13:6361. doi:10.3390/su13116361

8. Wang X, Wong YD, Yuen KF. Rise of ‘lonely’consumers in the post-COVID-19 era: a synthesised review on psychological, commercial and social implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:404. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020404

9. Ivascu L, Domil AE, Artene AE, et al. Psychological and behavior changes of consumer preferences during COVID-19 pandemic times: an application of GLM regression model. Front Psychol. 2022;13:879368. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.879368

10. Kutlubay OC, Cicek M, Yayla S. The impact of COVID-19 on online product reviews. J Prod Brand Manag. 2021. doi:10.1108/JPBM-12-2020-3281

11. Aron D, Kultgen O. The definitions of dysfunctional consumer behavior: concepts, content, and questions. J Consum Satisf Dissatisfaction Complain Behav. 2019;32:40–53.

12. Urueña A, Hidalgo A. Successful loyalty in e-complaints: fsQCA and structural equation modeling analyses. J Bus Res. 2016;69:1384–1389. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.112

13. Joe S, Choi C. The effect of fellow customer on complaining behaviors: the moderating role of gender. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2019;31:3116–3133.

14. Tronvoll B. Negative emotions and their effect on customer complaint behaviour. J Serv Manag. 2011;22:111–134. doi:10.1108/09564231111106947

15. Istanbulluoglu D, Leek S, Szmigin IT. Beyond exit and voice: developing an integrated taxonomy of consumer complaining behaviour. Eur J Mark. 2017;51:1109–1128. doi:10.1108/EJM-04-2016-0204

16. Nguyen Q, Ngo A, Mai V. Factors impacting online complaint intention and service recovery expectation: the case of e-banking service in Vietnam. Int J Data Netw Sci. 2021;5:659–666. doi:10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.8.001

17. Wang L, Wang L. Social facilitation or social loafing–threshold effect of group size on customer’s complaint intention. J Contemp Mark Sci. 2020;3(2):243–263.

18. Luo A, Mattila AS. Discrete emotional responses and face-to-face complaining: the joint effect of service failure type and culture. Int J Hosp Manag. 2020;90:102613. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102613

19. Ally S, Karpinski AC, Israeli AA. Customer behavioural analysis: the impact of internet addiction, interpersonal competencies and service orientation on customers’ online complaint behaviour. Res Hosp Manag. 2020;10:97–105. doi:10.1080/22243534.2020.1869468

20. Wattoo MU, Iqbal SMJ. Unhiding nexus between service quality, customer satisfaction, complaints, and loyalty in online shopping environment in Pakistan. SAGE Open. 2022;12:21582440221097920. doi:10.1177/21582440221097920

21. Zhan F, Luo W, Luo J. Exhibition attachment: effects on customer satisfaction, complaints and loyalty. Asia Pac J Tour Res. 2020;25:678–691. doi:10.1080/10941665.2020.1754261

22. Stephens N, Gwinner KP. Why don’t some people complain? A cognitive-emotive process model of consumer complaint behavior. J Acad Mark Sci. 1998;26:172–189. doi:10.1177/0092070398263001

23. Hornstein EA, Eisenberger NI. Exploring the effect of loneliness on fear: implications for the effect of COVID-19-induced social disconnection on anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2022;153:104101. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2022.104101

24. Ha HY, Muthaly SK, Akamavi RK. Alternative explanations of online repurchasing behavioral intentions: a comparison study of Korean and UK young customers. Eur J Mark. 2010;44(6):874–904. doi:10.1108/03090561011032757

25. Rufn R, Medina C, Rey M. Adjusted expectations, satisfaction and loyalty development. Serv Ind J. 2012;32:2185. doi:10.1080/02642069.2011.594874

26. Morgeson III FV, Hult GTM, Mithas S, et al. Turning complaining customers into loyal customers: moderators of the complaint handling–Customer loyalty relationship. J Mark. 2020;84:79–99. doi:10.1177/0022242920929029

27. Konuk FA. The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food. J Retail Consum Serv. 2018;43:304–310. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.04.011

28. Olshavsky RW, Miller JA. Consumer expectations, product performance, and perceived product quality. J Mark Res. 1972;19–21. doi:10.1177/002224377200900105

29. Rosillo-Díaz E, Blanco-Encomienda FJ, Crespo-Almendros E. A cross-cultural analysis of perceived product quality, perceived risk and purchase intention in e-commerce platforms. J Enterp Inf Manag. 2020;33:139–160. doi:10.1108/JEIM-06-2019-0150

30. Tsiotsou R. The role of perceived product quality and overall satisfaction on purchase intentions. Int J Consum Stud. 2006;30:207–217. doi:10.1111/j.1470-6431.2005.00477.x

31. Yilmaz C, Varnali K, Kasnakoglu BT. How do firms benefit from customer complaints? J Bus Res. 2016;69:944–955. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.038

32. Ngoc KM, Uyen TT. Factors affecting guest perceived service quality, product quality, and satisfaction–A study of luxury restaurants in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J Adv Manag Sci. 2015;3:284–291. doi:10.12720/joams.3.4.284-291

33. Kondasani RKR, Panda RK. Customer perceived service quality, satisfaction and loyalty in Indian private healthcare. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2015;28:452–467. doi:10.1108/IJHCQA-01-2015-0008

34. Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J Mark. 1985;49(4):41–50. doi:10.1177/002224298504900403

35. Bei LT, Chiao YC. An integrated model for the effects of perceived product, perceived service quality, and perceived price fairness on consumer satisfaction and loyalty. J Consum Satisf Dissatisfaction Complain Behav. 2001;14:125–140.

36. Zeithaml VA, Parasuraman A, Malhotra A. Service quality delivery through web sites: a critical review of extant knowledge. J Acad Mark Sci. 2002;30:362–375. doi:10.1177/009207002236911

37. Yang Z, Fang X. Online service quality dimensions and their relationships with satisfaction: a content analysis of customer reviews of securities brokerage services. Int J Serv Ind Manag. 2004;15:302–326. doi:10.1108/09564230410540953

38. Doherty NF, Ellis-Chadwick F, Huang Y, et al. Why consumers hesitate to shop online: an experimental choice analysis of grocery shopping and the role of delivery fees. Int J Retail Distrib Manage. 2006;34:334–353. doi:10.1108/09590550610660260

39. Santos J. E-service quality: a model of virtual service quality dimensions. Manag Serv Qual. 2003;13:233–246. doi:10.1108/09604520310476490

40. Lee GG, Lin H-F. Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping. Int J Retail Distrib Manage. 2005;33:161–176. doi:10.1108/09590550510581485

41. Cristobal E, Flavian C, Guinaliu M. Perceived e‐service quality (PeSQ): measurement validation and effects on consumer satisfaction and web site loyalty. Manag serv qual. 2007;24:68–81.

42. Hallowell R. The relationships of customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and profitability: an empirical study. Int j serv ind manag. 1996;7(4):27–42. doi:10.1108/09564239610129931

43. Bearden WO, Teel JE. Selected determinants of consumer satisfaction and complaint reports. J Mark Res. 1983;20:21–28. doi:10.1177/002224378302000103

44. Homburg C, Koschate N, Hoyer WD. The role of cognition and affect in the formation of customer satisfaction: a dynamic perspective. J Mark. 2006;70:21–31. doi:10.1509/jmkg.70.3.021

45. Oliver RL. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J Mark Res. 1980;17:460–469. doi:10.1177/002224378001700405

46. Rodríguez PG, Villarreal R, Valiño PC, et al. A PLS-SEM approach to understanding E-SQ, e-satisfaction and e-loyalty for fashion e-retailers in Spain. J Retail Consum Serv. 2020;57:102201. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102201

47. Szymanski DM, Hise RT. E-satisfaction: an initial examination. J Retail. 2000;76:309–322. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00035-X

48. LeHew ML, Wesley SC. Tourist shoppers’ satisfaction with regional shopping mall experiences. Int J Cult Tour Hosp Res. 2007;1:82–96. doi:10.1108/17506180710729628

49. Xu X, Liu W, Gursoy D. The impacts of service failure and recovery efforts on airline customers’ emotions and satisfaction. J Travel Res. 2019;58:1034–1051. doi:10.1177/0047287518789285

50. Khatoon S, Rehman V. Negative emotions in consumer brand relationship: a review and future research agenda. Int J Consum Stud. 2021;45:719–749. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12665

51. Huang MH. The theory of emotions in marketing. J Bus Psychol. 2001;16:239–247. doi:10.1023/A:1011109200392

52. Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Reflections on positive emotions and upward spirals. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;13:194–199. doi:10.1177/1745691617692106

53. Perlovsky L, Schoeller F. Unconscious emotions of human learning. Phys Life Rev. 2019;31:257–262. doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2019.10.007

54. Wen-Hai C, Yuan C-Y, Liu M-T, et al. The effects of outward and inward negative emotions on consumers’ desire for revenge and negative word of mouth. Online Inf Rev. 2018;43(5):818–841.

55. Habib MD, Qayyum A. Cognitive emotion theory and emotion-action tendency in online impulsive buying behavior. J Manag Sci. 2018;5:86–99. doi:10.20547/jms.2014.1805105

56. Singh J, Wilkes RE. When consumers complain: a path analysis of the key antecedents of consumer complaint response estimates. J Acad Mark Sci. 1996;24:350. doi:10.1177/0092070396244006

57. Landon EL. The direction of consumer complaint research. Adv consum res. 1980;7(1):335–338.

58. Fornell C, Westbrook RA. The vicious circle of consumer complaints. J Mark. 1984;48:68–78. doi:10.1177/002224298404800307

59. Kowalski RM. Complaints and complaining: functions, antecedents, and consequences. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:179. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.179

60. Luo H, Han X, Yu Y, et al. An empirical study on the effect of consumer complaints handling on consumer loyalty. In:

61. De Ruyter K, Wetzels M. Customer equity considerations in service recovery: a cross‐industry perspective. Int J Serv Ind Manag. 2000;11:91–108. doi:10.1108/09564230010310303

62. Svari S, Olsen LE. The role of emotions in customer complaint behaviors. Int J Qual Serv Sci. 2012;34:35–52.

63. Baker TL, Meyer T, Chebat J-C. Cultural impacts on felt and expressed emotions and third party complaint relationships. J Bus Res. 2013;66:816–822. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.06.006

64. Smith AK, Bolton RN. The effect of customers’ emotional responses to service failures on their recovery effort evaluations and satisfaction judgments. J Acad Mark Sci. 2002;30:5–23. doi:10.1177/03079450094298

65. Ravichandran T, Deng C. Effects of managerial response to negative reviews on future review valence and complaints. Inf Syst Res. 2022. doi:10.1287/isre.2022.1122

66. Rosenmayer A, McQuilken L, Robertson N, et al. Omni-channel service failures and recoveries: refined typologies using Facebook complaints. J Serv Mark. 2018;32(3):269–285. doi:10.1108/JSM-04-2017-0117

67. Tarhini B, Hayek D. The effect of proper complaint handling on customers’ satisfaction and loyalty in online shopping. In: Business Revolution in a Digital Era. Springer; 2021:405–421.

68. Bhadouria LS. Online complaint management system. Turkish J Comput Math Educa. 2021;12:5144–5150.

69. Hsu CL, Lin JCC. What drives purchase intention for paid mobile apps?–An expectation confirmation model with perceived value. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2015;14:46–57. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2014.11.003

70. Churchill GA, Surprenant C. An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. J Mark Res. 1982;19:491–504. doi:10.1177/002224378201900410

71. Fu X, Liu S, Fang B, et al. How do expectations shape consumer satisfaction? An empirical study on knowledge products. J Electron Commer Res. 2020;21:1–20.

72. Bhattacherjee A. Understanding information systems continuance: an expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001;25(3):351–370. doi:10.2307/3250921

73. Lee YJ, Kim IA, van Hout D, et al. Investigating effects of cognitively evoked situational context on consumer expectations and subsequent consumer satisfaction and sensory evaluation. Food Qual Prefer. 2021;94:104330. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104330

74. Yen YS. Factors enhancing the posting of negative behavior in social media and its impact on venting negative emotions. Manag Decis. 2016;54:2462–2484. doi:10.1108/MD-11-2015-0526

75. Hsieh YH, Yuan ST. Toward a theoretical framework of service experience: perspectives from customer expectation and customer emotion. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell. 2021;32:511–527. doi:10.1080/14783363.2019.1596021

76. Wu L. The antecedents of customer satisfaction and its link to complaint intentions in online shopping: an integration of justice, technology, and trust. Int J Inf Manage. 2013;33:166–176. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.09.001

77. Richins ML. Measuring emotions in the consumption experience. J Consumres. 1997;24:127–146. doi:10.1086/209499

78. Lin H, Zhang M, Gursoy D. Impact of nonverbal customer-to-customer interactions on customer satisfaction and loyalty intentions. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2020;32:1967–1985. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-08-2019-0694

79. Lin C, Lekhawipat W. How customer expectations become adjusted after purchase. Int J Electron Commer. 2016;20:443–469. doi:10.1080/10864415.2016.1171973

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.