Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 12

Evaluation of anterior capsular contraction syndrome after cataract surgery with commonly used intraocular lenses

Authors Hartman M, Rauser M , Brucks M, Chalam KV

Received 25 April 2018

Accepted for publication 12 June 2018

Published 8 August 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 1399—1403

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S172251

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Matthew Hartman,1 Michael Rauser,2 Matthew Brucks,2 KV Chalam2

1Department of Ophthalmology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine, Loma Linda, CA, USA; 2Department of Ophthalmology, Loma Linda University Eye Institute, Loma Linda, CA, USA

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to compare the incidence of anterior capsular contraction syndrome (ACCS) in cataract patients after implantation with one of two most commonly used hydrophobic acrylic lenses.

Setting: This study included patients from Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

Design: This study is a retrospective chart review.

Methods: In this study, 1,047 eyes of 811 patients with and without known ACCS risk factors who underwent successful phacoemulsification and intraocular lens (IOL) implantation were included. Eyes that sustained intraoperative capsular tears and patients with a postoperative follow-up of <1 month were excluded. Each patient underwent surgery by the same surgeon receiving either the SN60WF IOL or the ZCB00 IOL. The duration of postoperative follow-up along with the presence of ACCS and the dimensions of the anterior capsule opening in these cases were recorded. The incidence of ACCS between the two lenses was compared.

Results: ACCS was significantly (P=0.045) less frequent in those patients who received the ZCB00 lens compared to those who received the SN60WF lens, despite a significantly greater (P<0.0001) number of patients with ACCS risk factors in the ZCB00 cohort.

Conclusion: In a direct comparison of the ZCB00 and SN60WF IOLs, a lower incidence of ACCS was found with ZCB00 IOL.

Keywords: acrylic resins, biocompatible materials, capsule opacification, intraocular lens implantation, capsular phimosis, treatment outcome

Introduction

Progressive constriction of the anterior capsule opening remains an important late complication of cataract surgery. Anterior capsular contraction syndrome (ACCS) has been defined as the exaggerated reduction of the capsular bag diameter, which results from the contact of residual lens epithelial cells with the intraocular lens (IOL) near the continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (CCC).1 The incidence of contraction most commonly develops during the first 3 postoperative months, with subsequent decline in development.2,3 Capsule phimosis can be significant enough to disrupt the visual axis, necessitating a capsulotomy with a neodymium laser.4,5

Although the exact cause in many cases remains unclear, IOL composition and design have been shown to influence the development of ACCS.6–12 For example, it is well established that silicone IOLs lead to a greater degree of capsule contraction than acrylic IOLs.13,14 Additionally, a number of risk factors have been identified that are associated with an increased risk of ACCS, including pseudoexfoliation (PXE) syndrome,15 uveitis,16 retinitis pigmentosa,17 history of retinal surgery,18 and diabetes.19,20

We compared the incidence of ACCS between two most commonly used hydrophobic acrylic lenses, the AcrySof SN60WF (Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) and the Tecnis ZCB00 (Abbott Medical Optics Inc, Santa Ana, CA, USA). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that directly compared the rates of ACCS in these two popular IOLs. Made of the same material yet possessing different mechanical properties, studying ACCS in these lenses may shed light on biomechanical factors that influence capsule phimosis. By including patients with and without risk factors, this study also intended to determine which lens, if any, should be considered for patients at risk of developing ACCS.

Methods

This retrospective clinical study included 1,047 eyes of 811 patients from the Loma Linda University Eye Institute, Loma Linda, CA, USA. This study was approved by the Loma Linda University Hospital’s institutional review board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Individual consent from patients was waived, as it was a retrospective study. All collected data were de-identified before analysis to comply with institutional review board requirements of Loma Linda University Hospital Institutional Board. All patients underwent uncomplicated cataract surgery between July 2011 and May 2014 by the same surgeon (M.R.) using a 3.0 mm clear corneal incision, a well-centered 5 mm CCC, followed by phacoemulsification, cataract extraction, and IOL implantation. Two types of IOL were used: AcrySof SN60WF and Tecnis ZCB00. Size of CCC was measured and recorded at the each procedure.

Inclusion criteria consisted of successful creation of a CCC and IOL fixation in the capsular bag. Eyes that sustained intraoperative capsular tears and patients with a postoperative follow-up of <1 month were excluded. CCC that measured >5 mm was excluded.

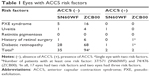

The duration of postoperative follow-up, type of IOL used, and presence of ACCS were recorded. The size of the capsule opening was measured by visualizing the capsulorhexis with a slit lamp and recording the diameters along the 90° and 180° meridians. The area within the capsule was calculated by taking the mean of the two diameters for use in the equation A=πr2.2 ACCS was considered to be present when the diameter of either meridian was measured to be <3.5 mm, corresponding to an opening area of approximately <10 mm2. Any documented history of PXE syndrome, uveitis, retinitis pigmentosa, previous retinal surgery, or diabetic retinopathy was noted (Table 1). The presence of mature cataracts was also recorded to evaluate any correlation with ACCS development.

The Fischer’s exact test was used to detect any difference between ACCS occurrence in the two groups, and the chi-squared test was used to detect any differences in risk factor quantity between the two groups. The statistical significance level was P≤0.05. Data were collected using Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS v22.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

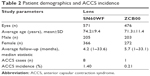

Of the 1,047 eyes included in the study (408 males and 639 females), 571 eyes had SN60WF implants and the remaining 476 eyes had ZCB00 implants. The average patient age was 74.2±9.4 years for the SN60WF lens and 71.3±11.4 years for the ZCB00 lens (Table 2). The average patient follow-up time was 4.2 months (range 1–33.6 months) for the SN60WF lens and 5.7 months (range 1–33.1 months) for the ZCB00 lens (Table 2).

| Table 2 Patient demographics and ACCS incidence |

ACCS occurred in eight eyes with the SN60WF lens and one eye with the ZCB00 lens, a borderline statistically significant difference of P=0.045 (0.21% vs 1.40%, respectively). The mean area within the rim of the capsule opening in documented cases of ACCS at the last post-op visit was 9.8±2.6 mm2. The median time to detection of ACCS was 1.4 months (range 1–19 months). Only one case of ACCS (ZCB00 lens) required Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy for visually significant ACCS.

Of the eyes implanted with the SN60WF lens, 37/571 (6.5%) had at least one ACCS risk factor compared to 74/476 (16%) with the ZCB00 lens, a statistically significant difference of P<0.0001. Of the nine total cases of ACCS, three patients had known ACCS risk factors (Table 1). No cases of ACCS were observed in patients with mature cataracts.

Discussion

This study shows a reduction in ACCS occurrence in eyes implanted with the ZCB00 lens compared to eyes implanted with the SN60WF lens. Differences in ACCS rates between IOL models have principally been attributed to differences in IOL composition and design.6–12 While both lenses in this study share a similar hydrophobic acrylic composition, there are minor differences in their design (Table 3). Both lenses have a posterior square edge designed to reduce the incidence of posterior capsule opacity; however, the ZCB00 features a 360° continuous edge, while the edge of the SN60WF is interrupted at the optic–haptic junctions. The influence of the optic edge on ACCS is controversial. While lenses with square edges led to decreased posterior capsule opacification (PCO), these edges increased the amount of anterior capsule shrinkage.10 However, more recently, Miyata et al8 concluded that a square edge was not a risk factor for ACCS. Given this discrepancy, other distinctions between the lenses were explored.

| Table 3 Lens specifications |

Differences in the biomechanical properties of these lenses may have contributed to the higher rate of ACCS seen in the SN60WF lens in our study. In a comparative study of hydrophobic IOLs, Bozukova et al21 found that the SN60WF and the ZCB00 lenses differed in the amount of compressive force the haptics applied to the capsular bag. Using various diameters to represent different sizes of capsules, it was shown that the ZCB00 lens haptics applied a 14%–60% greater force to the capsules than the SN60WF lens haptics.21 It is hypothesized that a larger outward force applied by lens haptics provides increased opposition to the contractile forces of ACCS, stabilizing the bag and reducing zonular tension. Capsule tension imbalances were used in prior studies to explain the pathogenesis of ACCS. Cochener et al13 theorized that the increased flexibility of the silicone lens is responsible for the higher rate of ACCS observed in these lenses than in lenses of other materials. Similarly, zonular friability in PXE syndrome is a proposed ACCS risk factor.15,22 Considering these findings, it is likely that the stronger haptics of the ZCB00 lens provided structural integrity to the capsular bag and contributed to its lower incidence of ACCS observed in our study.

The low rate of ZCB00 ACCS in our study was independent of cohort risk factors. During the course of this study, a trend toward higher ACCS rates in SN60WF IOLs was noted by the surgeon (M.R.) who then chose the ZCB00 IOL for patients with ACCS risk factors. The results of our study reflect the surgeon’s preference, as 37/571 (6.5%) eyes with the SN60WF IOL had at least one risk factor, while 74/476 (16%) eyes with the ZCB00 IOL had at least one risk factor, as noted in the “Results” section. Of the 74 eyes receiving the ZCB00 lens that had at least one risk factor, only one developed ACCS (1.3%).

Notably, there has been another study that used the ZCB00 lens to examine ACCS, and its results were similar to those of our study. In a clinical trial, Kahraman et al23 compared ACCS between the ZCB00 arm and the AcrySof SA60AT arm (also hydrophobic acrylic) and found that no patients in the ZCB00 arm developed capsular phimosis, while some degree of phimosis was found in 17% of the patients in the SA60AT arm.

What was known

- ACCS is a potentially visually significant complication following cataract extraction, with documented risk factors including silicone IOLs, PXE, diabetic retinopathy, and a history of uveitis or retinal surgery.

- To the best of our knowledge, no study has directly compared the incidence of ACCS between the AcrySof SN60WF and the Tecnis ZCB00, two popular IOLs.

What this paper adds

- In a direct comparison of the ZCB00 and SN60WF IOLs, a lower incidence of ACCS was found in the ZCB00 IOL.

- The ZCB00 IOL should be considered in patients at risk for ACCS development.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although most cases of ACCS develop within 3 months postoperatively and the mean follow-up time in our study was 4.2 and 5.7 months for the SN60WF and ZCB00 lens, respectively, 15.7% of patients with the SN60WF lens and 13.9% of patients with the ZCB00 lens did not return after their 1-month visit. Furthermore, while our criteria for ACCS (a capsular opening area of <10 mm2) is used to define significant capsular contraction by various authors,15,24 the incidence of ACCS in our study may vary from other studies due to the absence of a universally accepted method of quantification.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that using the ZCB00 lens may result in a significantly lower risk of the development of ACCS compared to using the SN60WF lens, a difference that may be partially explained by increased mechanical rigidity of the ZCB00 haptics. We suggest the Tecnis ZCB00 IOL be considered for patients at risk for capsular contraction following cataract extraction.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the support of Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA, USA.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Frezzotti R, Caporossi A, Mastrangelo D, et al. Pathogenesis of posterior capsular opacification. Part II: histopathological and in vitro culture findings. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(3):353–360. | ||

Park TK, Chung SK, Baek NH. Changes in the area of the anterior capsule opening after intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(9):1613–1617. | ||

Kimura W, Yamanishi S, Kimura T, Sawada T, Ohte A. Measuring the anterior capsule opening after cataract surgery to assess capsule shrinkage. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24(9):1235–1238. | ||

Deokule SP, Mukherjee SS, Chew CK. Neodymium:YAG laser anterior capsulotomy for capsular contraction syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2006;37(2):99–105. | ||

Chéour M, Mghaieth K, Bouladi M, Hasnaoui W, Mrabet I, Kraiem A. Nd:Yag laser treatment of anterior capsule contraction syndrome after phacoemulsification. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30(9):903–907. | ||

Corydon C, Lindholt M, Knudsen EB, Graakjaer J, Corydon TJ, Dam-Johansen M. Capsulorhexis contraction after cataract surgery: comparison of sharp anterior edge and modified anterior edge acrylic intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(5):796–799. | ||

Hayashi K, Hayashi H. Intraocular lens factors that may affect anterior capsule contraction. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(2):286–292. | ||

Miyata K, Kato S, Nejima R, Miyai T, Honbo M, Ohtani S. Influences of optic edge design on posterior capsule opacification and anterior capsule contraction. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85(1):99–102. | ||

Sacu S, Menapace R, Findl O. Effect of optic material and haptic design on anterior capsule opacification and capsulorrhexis contraction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(3):488–493. | ||

Sacu S, Menapace R, Buehl W, Rainer G, Findl O. Effect of intraocular lens optic edge design and material on fibrotic capsule opacification and capsulorhexis contraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(9):1875–1882. | ||

Tsinopoulos IT, Tsaousis KT, Kymionis GD, et al. Comparison of anterior capsule contraction between hydrophobic and hydrophilic intraocular lens models. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248(8):1155–1158. | ||

Hayashi K, Hayashi H. Comparison of the stability of 1-piece and 3-piece acrylic intraocular lenses in the lens capsule. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(2):337–342. | ||

Cochener B, Jacq PL, Colin J. Capsule contraction after continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis: poly(methyl methacrylate) versus silicone intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25(10):1362–1369. | ||

Zambarakji HJ, Rauz S, Reynolds A, Joshi N, Simcock PR, Kinnear PE. Capsulorhexis phymosis following uncomplicated phacoemulsification surgery. Eye. 1997;11(pt 5):635–638. | ||

Hayashi H, Hayashi K, Nakao F, Hayashi F. Anterior capsule contraction and intraocular lens dislocation in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(12):1429–1432. | ||

Davison JA. Capsule contraction syndrome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19(5):582–589. | ||

Sudhir RR, Rao SK. Capsulorhexis phimosis in retinitis pigmentosa despite capsular tension ring implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(10):1691–1694. | ||

Matsuda H, Kato S, Hayashi Y, et al. Anterior capsular contraction after cataract surgery in vitrectomized eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(1):108–109. | ||

Kato S, Oshika T, Numaga J, et al. Anterior capsular contraction after cataract surgery in eyes of diabetic patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(1):21–23. | ||

Hayashi Y, Kato S, Fukushima H, et al. Relationship between anterior capsule contraction and posterior capsule opacification after cataract surgery in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(7):1517–1520. | ||

Bozukova D, Pagnoulle C, Jérôme C. Biomechanical and optical properties of 2 new hydrophobic platforms for intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39(9):1404–1414. | ||

Assia EI, Apple DJ, Morgan RC, Legler UF, Brown SJ. The relationship between the stretching capability of the anterior capsule and zonules. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32(10):2835–2839. | ||

Kahraman G, Schrittwieser H, Walch M, Storch F, Nigl K, Ferdinaro C, Amon M. Anterior and posterior capsular opacification with the Tecnis ZCB00 and AcrySof SA60AT IOLs: a randomized intraindividual comparison. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(7):905–909. | ||

Hayashi K, Hayashi H, Matsuo K, Nakao F, Hayashi F. Anterior capsule contraction and intraocular lens dislocation after implant surgery in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(7):1239–1243. | ||

AcrySof SN60WF [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Alcon Surgical Inc; 2010. | ||

Tecnis ZCB00 [package insert]. Santa Ana, CA: Abbott Medical Optics Inc; 2007. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.