Back to Journals » Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology » Volume 8

Endoscopic therapy in chronic pancreatitis: current perspectives

Received 8 July 2014

Accepted for publication 15 September 2014

Published 17 December 2014 Volume 2015:8 Pages 1—11

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S43096

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Editor who approved publication: Professor Andreas M. Kaiser

Andrada Seicean, Simona Vultur

Regional Institute of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Cluj-Napoca, University of Medicine and Pharmacy "Iuliu Hatieganu", Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Abstract: Endoscopic therapy in chronic pancreatitis (CP) aims to provide pain relief and to treat local complications, by using the decompression of the pancreatic duct and the drainage of pseudocysts and biliary strictures, respectively. This is the reason for using it as first-line therapy for painful uncomplicated CP. The clinical response has to be evaluated at 6–8 weeks, when surgery may be chosen. This article reviews the main possibilities of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) therapies. Endotherapy for pancreatic ductal stones uses ultrasound wave lithotripsy and sometimes additional stone extractions. The treatment of pancreatic duct strictures consists of a single large stenting for 1 year. If the stricture persists, simultaneous multiple stents are applied. In case of unsuccessful ERCP, the EUS-guided drainage of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) or a rendezvous technique can solve the ductal strictures. EUS-guided celiac plexus block has limited efficiency in CP. The drainage of symptomatic or complicated pancreatic pseudocysts can be performed transpapillarily or transgastrically/transduodenally, preferably by EUS guidance. When the biliary stricture is symptomatic or progressive, multiple plastic stents are indicated. In conclusion, as in many fields of symptomatic treatment, endoscopy remains the first choice, either by using ERCP or EUS-guided procedures, after consideration of a multidisciplinary team with endoscopists, surgeons, and radiologists. However, what is crucial is establishing the right timing for surgery.

Keywords: chronic pancreatitis, treatment, endoscopy, ERCP, endoscopic ultrasound

Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is an irreversible and progressive inflammatory process, featuring pathological modifications of fibrosis, inflammatory infiltration, and the destruction of exocrine and endocrine tissue. As a result, there are specific morphological changes in the parenchyma and pancreatic ducts.

The most common clinical presentation for patients with CP is abdominal pain,1 which significantly decreases the quality of life.

Pain is caused by pancreatic hyperstimulation, ischemia, necrosis,2 oxidative stress, obstruction of pancreatic ducts, and necrosis–fibrosis mechanism.3–5 Inflammation and damage of the pancreatic nerve is also considered as a cause of pain in CP.6,7

Endoscopic therapy in CP aims to provide pain relief and to treat local complications, by using the decompression of the pancreatic duct and the drainage of pseudocysts and biliary strictures, respectively.

The European Society of Gastroenterology (ESGE) recommends endoscopic therapy as the first-line therapy for painful uncomplicated CP. The clinical response has to be evaluated at 6–8 weeks; if it appears to be unsatisfactory, the patient’s pancreatic problems should be discussed again in a multidisciplinary team with endoscopists, surgeons, and radiologists. Subsequently, the surgical options are to be considered, particularly for patients with a poor outcome following endoscopic therapy.8 Comparing pain relief by ductal endoscopic procedures to surgery, two of three randomized control trials were favorable to surgery in long-term follow-up.7,9–11 However, because of the irreversibility of surgery, the current guideline gives priority to endoscopic therapy.

Endotherapy of pancreatic ductal stones

The decompression of the ducts is the first therapeutic option for patients suffering from pain caused by intraductal obstruction and ductal hypertension. It can be done endoscopically by performing pancreatic sphincterotomy, stones lithotripsy, and extraction or stenting.

Pancreatic sphincterotomy alone is rarely used today as a unique endoscopic method of treatment, because surgical sphincterotomy and sphincteroplasty in CP have been associated with modest results.12 However, this procedure is indicated in rare cases where the obstruction is located in the papillary orifice, with uniform dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (MPD) above.

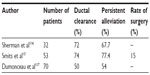

Extraction of the pancreatic stones can be done with the Dormia basket or the balloon associated with pancreatic sphincterotomy. It is indicated when the stone is not impacted in the pancreatic duct, in the head of the pancreas, or when there is a small number of stones as the only significant feature of CP.13–18 Complete or partial pain relief after this type of procedures is 50%–77% (Table 1).

| Table 1 Results of pain treatment in chronic pancreatitis after endoscopic sphincterotomy and extraction of pancreatic stones |

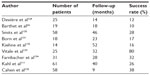

In case of large impacted intraductal stones >4 mm in diameter, being larger than the duct size, or located above a stenosis, in the head of the pancreas, the ultrasonic lithotripsy procedures (extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy [ESWL]) should be done as the first procedures19–22 (Table 2), followed sometimes by the endoscopic extraction of the fragments.16,17 The aim of ESWL is to obtain fragments less than 3 mm in diameter to facilitate their expulsion or extraction. Intraductal laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy through a pancreatoscope or spyscope are technically difficult and are only to be considered as a second-line management after ESWL has failed.8,23,24

| Table 2 Results of extracorporeal lithotripsy in chronic pancreatitis |

The complete relief of pain in idiopathic CP after ESWL as a unique method of treatment was seen in 414 of 1,006 patients (42%) in the medium follow-up of 24–36 months. Only 5% of the patients had severe remnant pain.25 Another long-term study of ESWL as the initial therapy for CP showed that many procedures are needed during a lifetime. However, partial pain relief was seen in 85%, complete pain relief with no narcotic use in 50%, while surgery was avoided in 84% of the patients.26

A meta-analysis about ESWL treatment showed that ductal clearance is obtained in 37.5%–100% of the cases.27 In many studies, there was no correlation between the fragmentation of the stones and the rate of ductal clearance.27 More than 90% of patients needed less than three sessions of ESWL.25 Recurrence of stones was seen in 51 patients (14.01%) in the intermediate follow-up group, and in 62 patients (22.8%) in the >60 months long-term group.28 Secretin administration during ESWL may help the stone fragmentation and it facilitates the excretion of the small pancreatic stones.29 Also, stopping smoking after ESWL may improve outcomes.26

Complications that may occur after ESWL are acute pancreatitis, biliary or pancreatic sepsis, and gastric submucosal hematoma. Although there have been attempts to assess the effect of ESWL on endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, the existing data are insufficient for a conclusion.27

With the use of all these methods, pain improvement is 95% after procedures and about 40%–76% are painless in 2–4 years (Table 3). It is still doubtful whether the residual pain depends on the number, shape, and location of the remaining stones.13 The resistance of ductal stenosis or the neurogenic mechanism may be responsible for persistent pain.17

| Table 3 Results of pain treatment in chronic pancreatitis after sphincterotomy, endoscopic extraction, and extracorporeal lithotripsy of pancreatic stones |

ESWL versus ESWL followed by stones extraction and stenting when pancreatic strictures were associated was assessed in a randomized study. Pain recurrence at 2 years was 38% in the first group versus 45% in the second group, with the costs being three times lower in the first group.30 More than half of the patients had no pain relapse during a median follow-up of 4 years in both groups, with higher costs in the second group.30

ESGE recommendations for the treatment of patients with uncomplicated painful CP and intraductal stones ≥5 mm are ESWL as a first step, immediately followed by endoscopic extraction of stone fragments. ESWL alone should be preferred over ESWL combined with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Endoscopic attempts to extract radiopaque MPD stones without prior stone fragmentation should be considered only for stones <5 mm, preferably in a small number, and located in the head or body of the pancreas. Intraductal lithotripsy is to be attempted only after the failure of ESWL.8

Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stricture

Strictures of the MPD are seen in about half of patients of CP, usually located in the pancreatic head, being caused by inflammation or fibrosis. MPD strictures are defined as a high-grade narrowing of MPD with one of the following: 1) MPD dilatation >6 mm beyond the stricture or when the contrast fails to flow alongside the stricture or 6 Fr nasopancreatic tube. The presence of multiple or tail strictures are the main negative predictors of the relapsing pain.21,30

The stenoses are dilated with a balloon or a catheter, followed by the placement of a plastic stent.18,31 If the stenosis can be overpassed, the MPD is decompressed and the pain is relieved (Table 4). Pancreatic stenting was seen as an alternative to MPD decompression surgery, which is associated with a mortality rate of 2%–5%. Although the sphincterotomy is not necessary in order to place the stent, some authors recommend it for preventing postprocedure pancreatitis. The stent size is chosen to be at least as large as the pancreatic duct, in order to dilate the stenosis. The 10 Fr is less likely to be obstructed, but its placement is more difficult than a 5 Fr stent. The stents should be long enough to overpass the stenosis, and short enough to minimize the ductal changes.

| Table 4 Results of pain treatment in chronic pancreatitis after sphincterotomy, stone extraction, and pancreatic stenting |

The protocol concerning the number and the duration of stenting suggested initially the placement of a 10 Fr stent every 6 months with pain relief in 70%–94% of patients. After removing the stent placed for 3 months in patients who stopped drinking alcohol, pain relief was obtained in 58% of patients at 46 months’ follow-up.32 Recurrence of pancreatic strictures was reported in 38% of patients after 2 years of follow-up.33 Long-term pain relief was obtained in 5 years after stent removal in eight of 14 patients.34

When dilation with a single stent is not achieved, the placement of multiple stents for 6–12 months is recommended, resulting in 84% of patients as asymptomatic and 10.5% of patients with symptomatic recurrent stenosis at 38 months’ follow-up.35

The size of MPD after stenting does not predict the pain response, because pain alleviation can occur when the stent is obstructed, with the pancreatic juice leaking around it.36,37 After endoscopic clearance of the MPD, the placement of a stent for ductal stenosis causes a slight reduction in the recurrence of symptoms (21% vs 23%). Reversible ductal changes after stenting may occur in most of the patients, thus stenting after complete extraction of ductal stones is not recommended.38

The use of non-covered metal stents for preventing stone recurrence after lithotripsy in patients with pancreatic stricture was accompanied by mucosal hyperplasia inside the stent. But recent studies performed with specially made auto-expandable metal stents showed a partial improvement in pain after stent placement39 and no migration of the stent.40 Maintaining the metal stent for 4–7 days produces a dilation of strictures and allows the endoscopic extraction of stones above the stenosis.41 However, asymptomatic de novo focal pancreatic duct strictures after metal stent retrieval have been noted.42 New biodegradable stents were tested on animals, but further results are still expected.43

Stenting is associated with complications such as: occlusion, ductal stenosis, and stent migration. Stent occlusion (with lithostathine and albumin)44 may induce local infection and the formation of pseudocysts, with the medium duration to occlusion being 2 months (2–38 months). Since the pain relapses quite rapidly after stent removal, there is a need to repeat the stenting. Some prefer regular replacement every 3 months,45,46 others only after the stent has been occluded and symptomatic (on demand).47 The causes of stent occlusion may be: diameter over 8.5 Fr, length of more than 8 cm, or intake of pancreatic enzymes, but the occlusion could be a “scam” because the pancreatic juice may leak around the intraductal precipitates.48 The ESGE recommends to treat the dominant MPD stricture by inserting a single 10 Fr plastic stent, with stent exchange planned within 1 year even in asymptomatic patients to prevent complications related to longstanding pancreatic stent occlusion.8 Simultaneous placement of multiple, side-by-side, pancreatic stents could be applied more extensively, particularly in patients with MPD strictures persisting after 12 months of single plastic stenting.

Another complication is the migration of the stent, which can be proximal, into the duodenum (5.2%), or distal, toward the tail of the pancreas (7.5%). The main way to reduce the migration is to use stents with side wings, especially pigtail stents.49 The use of S form stents avoids this complication and determines the improvement of duct stenosis in 40% of patients.50

Ductal changes, such as ductal stenosis, were described in 54% of stented patients.51 Some authors claim that the stent itself does not induce ductal changes, but the ductal decompression reveals new stenosis masked previously.52

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of the MPD

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage of the MPD is a second-line procedure indicated when ERCP is unsuccessful, caused by the inability to cannulate the MPD (severe inflammation, previous surgery, postsurgical stricture) or difficult endotherapy (tight stenosis, large stone, MPD rupture, pancreas divisum). In practice, there are only few cases in which ERCP cannot be successfully performed by an experienced endoscopist. Thus, only a very small number of patients, namely those in whom ERCP fails and surgery cannot be performed safely, are good candidates for pancreaticogastrostomy performed by EUS.8

The technique consists of puncturing the MPD through the gastric or duodenal wall. It creates a fistula that allows drainage through or near the stent, even in cases of stent occlusion. After advancing the guide wire into the MPD, the transpapillary technique (rendezvous technique) can also be performed.

Using the transluminal approach or the transpapillary rendezvous approach, EUS-guided drainage of the MPD remains technically challenging because of the difficulty in orienting the endoscope along the axis of the duct, difficult dilatation of the transmural tract due to pancreatic fibrosis, or the acute angle of the needle in relation to the MPD.

Using this technique, complete or major pain relief occurred in 69% of patients, but the probability of remaining free of pain sharply dropped over time, to 20% after 450 days; a malignant etiology for complete MPD obstruction has been diagnosed in five patients within 1 year after the procedure.53 Despite success rates of 68%–75%, the complication rates were important in all series published (5%–43%); the complications included perforations, bleeding, pancreatitis, fever, and postprocedural pain.53–57 Migration and occlusion of stents were frequent (20%–55% of patients) and the placement of stents on each side of the puncture place (side-by-side) was proposed.53 EUS-guided drainage of the MPD should continue to be confined to tertiary care centers and very experienced endoscopists.

Endoscopic therapy in the presence of pancreas divisum

Endoscopic therapy in the presence of pancreas divisum includes minor papilla sphincterotomy and stenting using 5–10 Fr stents, depending on the size of the dilated pancreatic duct. It is indicated only in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis with or without features of CP. The recurrence episodes are reduced in 40–60% of cases.58 In patients with pancreas divisum and painful symptoms, but no imaging features of CP, pain relief after minor papilla sphincterotomy is better than in patients with CP secondary to pancreas divisum (43% vs 21% after 29 months’ follow-up). These findings may be explained by the fact that minor papilla sphincterotomy does not produce the reversibility of CP lesions already done.59 In the long term, the sphincterotomy has better results than stenting, with a reduced risk of complications. If the dorsal pancreatic duct is not dilated, the stenting is indicated for a period of only 3–6 months.60,61

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block

In case of pancreatic pain resistant to standard procedure, a solution could be to block the pancreatic sympathetic innervation such as celiac plexus. This is usually situated from the T12-L1 disc space to the middle of the L2 vertebral body and comprising a dense network of ganglia around the aorta. Sympathetic blockade can be achieved by chemical or surgical celiac ganglia or thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy. Chemical sympathectomy can be done using absolute alcohol injected into the celiac plexus under CT or EUS guidance. Analgesia is obtained only for a period of 8–12 months and, therefore, the therapeutic indications for this process are limited.62,63

The approach was originally developed transcutaneously by posterior approach, ultrasound- or CT-guided, but it was associated with paraplegia by affecting the dura mater or with pneumothorax by affecting the pleura. This is the reason for preferring the anterior approach, in the EUS-guided manner. It consists of temporary inhibition of the celiac plexus by using a combination of local anesthesia and steroids, with the aim of reducing pain and improving the quality of life.64 Sometimes the celiac ganglia can be seen as a unique or concatenate hypoechoic structure, less well-delineated, with some whitish strands inside,65 situated on the left side of the celiac trunk, usually between the celiac trunk and the left adrenal gland. Sometimes it may be multiple, appearing as a chain.

ESGE recommends considering celiac plexus block (CPB) only as a second-line treatment for pain in CP; EUS-guided CPB should be preferred over percutaneous CPB.8 The indication is pain in CP, but some studies included pain accompanying moderate pancreatitis66 or patients with pain that had not responded to other forms of treatment.67

The majority of studies used the bilateral injection technique over the central technique, which is considered equally safe, but with close and contradictory results concerning the alleviation of pain,66,68 with need of a placebo-controlled trial.69 Direct injection of triamcinolone within the celiac ganglia (13 patients), compared with alcohol injection (five patients), yielded disappointing results regarding pain alleviation (38% vs 80%).70 In another study using triamcinolone 40 mg injection in each part of the celiac trunk, the improvement of pain was seen in 55% of patients after 8 weeks of follow-up, and in 26% of patients after 12 weeks of follow-up, but with no effect in younger patients or with previous surgery.71

The question of cost-effectiveness remains unresolved. Some studies followed up the patients for only 1–4 weeks.68,70 The only study with an extended follow-up period showed duration of pain relief even up to 673 days. This raises the question of whether the natural course of the disease may have been responsible, because there were no data indicative of the level of severity of CP: the duration of disease from the onset of pain, presence of diabetes, or calcifications.66

In many studies, pain alleviation varied from 55% to 70%, with a short follow-up duration.66–68,71 While technical success has been high, long-term pain relief is disappointing. Persistence of pain alleviation for as long as 24 weeks was seen in no patients67 or in only 10% of patients (was 55% after EUS-guided CPB).71 In addition, about 40% (8-week group follow-up), and 30% (24-week group follow-up) of the EUS-guided CPB had continued benefit, compared to 12% (12-week follow-up) in the CT-guided CPB, clearly suggesting the superiority of the EUS method.72 Two meta-analyses showed efficacy in managing chronic abdominal pain with this method in 51.46%72 and 59.45%73 of patients, respectively. The remaining pain could have been caused by sympathetic stimulation originating from T9-T11 or from somatic route innervation coming from extrapancreatic tissue.

CPB has the same efficiency compared to thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy for pain treatment in CP, but with a better quality of life.74

The side effects of this method are diarrhea and hypotension due to parasympathetic activity. Pain exacerbation for about 48 hours after the procedure may occur in 9% of patients.75 The risk of paraparesis is reduced for the anterior approach, but peripancreatic abscess and retroperitoneal hemorrhage76 were noted. More recently, lethal necrosis and perforation of the stomach and the aorta after multiple EUS-guided CPB have been reported,77 so this method is not as benign as previously believed.

Infectious complications are uncommon, but potentially serious. In a series of 90 patients, only one patient developed an infectious complication (peripancreatic abscess), which was resolved with a 2-week course of antibiotics.74 Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered in patients who are under acid suppression, but this is not routinely recommended because concentrated alcohol has sufficient bactericidal effect.64 The rate of major complications seemed very low (0.6%).78

Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts

Pseudocysts are encountered in about 30% of patients with CP. As spontaneous resolution is seen in less than 10%, some criteria of nonresolution were established, such as: persistence over 6 weeks, pancreatic duct anomaly (except for communication with the pancreatic duct), proven CP, and pseudocyst thick wall.79

Pseudocyst treatment can be done percutaneously, endoscopically, or surgically. Endoscopic therapy, as the first-line therapy for uncomplicated chronic pseudocysts for which the treatment is indicated, provides similar long-term results compared to surgery, at a lower cost, with shorter hospitalization and better quality of life during the first months following treatment.

Before choosing the endoscopic treatment, it is necessary to accurately determine the communication with the Wirsung duct by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ERCP examination and to differentiate potential neoplastic cystic lesions (MRI and EUS-FNA [fine needle aspiration]). Moreover, to avoid pseudocyst relapse, described in 4%–17% of cases after 6–9 months’ of follow-up,77,78,80 communication with a secondary pancreatic duct should be assessed very carefully.

Indications for treatment are:

- Complicated pseudocysts (one criterion is sufficient): compression of large vessels, obstruction of the stomach or duodenum, stenosis of MPD due to compression, infected pseudocyst, pleural pancreatic fistula;

- Symptomatic pseudocysts: nausea, vomiting, pain, early satiety, upper gastrointestinal bleeding (10%–20%).

If arterial pseudoaneurysms are detected in the vicinity of the pancreatic pseudocysts, arterial embolization should be considered prior to pseudocyst drainage.8

Transpapillary/transductal endoscopic drainage

Transpapillary/transductal endoscopic drainage with stent placement for a period of 4–6 weeks is recommended for small pseudocysts communicating to the MPDs located in the head or the body of the pancreas, but this is usually required in a limited number of cases.81 The immediate success is about 85%. Double-pigtail stents of 10 Fr are preferred to prevent migration. A favorable predictor of successful therapy is a dilated Wirsung duct above a stenosis overpassed by the stent. Morbidity is 6% and mortality is 0%.80–90 Modest results are obtained when the pseudocyst is older than 6 months, or smaller than 6 cm.91 Stents should be left in place for a longer duration as their removal within 2 months is associated with a higher incidence of pseudocyst recurrence.8

Transmural conventional endoscopic drainage (cystogastrostomy or cystoduodenostomy) is indicated for pseudocysts noncommunicating with the MPD, with ductal wall thickness <1 cm and compressive on the digestive tract. The success rate varies between 74% and 94%; morbidity is about 9%–17% and mortality is 0%. Difficulties occur when gastric portal hypertension is present. EUS-guided drainage has been reported, especially for collections without bulging onto the gut wall or with parietal vessels, due to portal hypertension.92–94 The success rate is 88%–95%. The main limitation is the location of fluid collection further than 1–1.5 cm from the gut wall.45,95,96 It is important to avoid these methods for pancreatic cystic neoplasms or for pseudoaneurysms. Technically, cystoduodenostomy should be preferred over cystogastrostomy if both routes are deemed equally feasible. ESGE recommends to insert at least two double-pigtail plastic stents; these should not be retrieved before cyst resolution as determined by cross-sectional imaging and not before, 2 months of stenting.8 Unfavorable results are found for infected pseudocysts, with thick wall or for patients with walled off pancreatic necrosis or with portal hypertension.90

EUS-guided drainage

EUS-guided drainage is indicated in the case of portal hypertension or in the absence of luminal bulging. Although known as a technique since 1998, published series of EUS drainage of pseudocysts has reported a success rate of 88%–95%, including infected pseudocysts.97,98 The puncture site is enlarged either by balloon dilatation or by coagulation. Negative predictors of treatment response are ductal stenosis and rupture of the Wirsung duct.99 Using the axial echoendoscope appears to facilitate the approach to the pseudocysts, which are difficult to locate.100 When it is necessary, endoscopic transmural drainage may be combined with EUS drainage.101 More recently, the success rate for plastic or metallic stents is over 95%, with similar outcome and complete resolution when the stent was removed within 3 months.102,103 While current evidence suggests that placement of metal stents is technically feasible in patients with pseudocysts, there are no data to prove that metal stents are superior to plastic stents in terms of treatment efficacy, complications, recurrence rates, or cost-effectiveness. Randomized trials with long-term follow-up are needed to compare metal and plastic stents for drainage. The main advantages would be the possibility to create a larger diameter access fistula for drainage, to increase the final success rate, and to reduce the time to resolution. The major disadvantages are stent migration and bleeding. The use of metallic stents with anti-migration systems could avoid this complication.104

Conventional endoscopic drainage and EUS-guided drainage have been compared in some papers. In a prospective nonrandomized study, the two approaches seemed equally safe and effective,82 but this was not confirmed by a nonrandomized study of 53 patients, where EUS represented a salvage method in the case of failure of conventional endoscopic drainage (possible only in 57% of patients), owing to non-bulging pseudocysts or the location in the tail of the organ, but it was a more time-consuming procedure.105 EUS drainage had a duration of 75 minutes and transmural drainage 45 minutes, with similar success rates. The conclusion of this study was that EUS should be reserved for pseudocysts located in the tail of the pancreas, because these are unlikely to cause luminal compression or they are technically difficult to access. Also, EUS assessment would identify a tumor in 5% of pseudocysts.105 Another randomized clinical trial showed a significantly better success rate for EUS- than for conventional endoscopic-guided drainage (100% vs 33%), despite the small number of patients (30 patients), even after statistical adjustment for luminal compression, with a lower rate of life-threatening massive bleeding.106 A different study also confirmed a significant advantage for EUS over conventional endoscopic drainage (94% vs 72%); both were considered first-line methods for the treatment of bulging pseudocysts, but the authors recommended that EUS-guided drainage should be preferred for non-bulging pseudocysts.107 In a randomized trial, EUS-guided and surgical drainage appear to have the same rates of treatment success, complications, and reinterventions.108 Also, costs are lower with the EUS procedure compared to surgery.140

The rate of complications is about 18%, including bleeding, infection, and pneumoperitoneum or stent migration.82 Perforation at the site of transmural stenting was more common with pseudocysts involving the uncinate region.109 Complications seem to be more common in pseudocysts with recent history of acute pancreatitis and the placement of straight stents, but no significant differences were observed between the placement of one or two stents, or between patients with or without nasocystic drainage.110

Common bile duct stenosis treatment

Biliary obstruction occurs during the course of CP in 3%–23% of patients, being related to fibrosis and pseudocyst compression. ESGE recommendations of treatment are for symptomatic strictures, secondary biliary cirrhosis, biliary stones, progression of biliary stricture, or asymptomatic elevation of serum alkaline phosphatase (>2 or 3 times the upper limit of normal values) and/or of serum bilirubin for longer than 1 month.8

Stenting with one biliary plastic prosthesis is associated with a low success rate, with frequent relapses, mainly related to the presence of calcifications (Table 5).111 This is the reason for the recommendation of temporary (1-year) placement of multiple, side-by-side, plastic biliary stents. The stents should be exchanged every 3 months, because the risk of cholangitis is very high, but quite often the compliance of alcoholic patients is low. One nonrandomized series has compared long-term results after temporary treatment with single versus multiple simultaneous plastic stents; it showed overall clinical success in 24% vs 92% of patients.112

| Table 5 Biliary stenting in chronic pancreatitis |

Much hope was invested in metallic biliary stents. Although uncovered stents are not advisable for treating biliary strictures, partially or completely covered stents are promising, with 50%–80% long-term success, with a low recurrence rate (14%); their removal has recently been proved as feasible in 75% of patients.113–115

The choice between endoscopic and surgical treatment should rely on local expertise, local or systemic patient comorbidities (eg, portal cavernoma, cirrhosis), and expected patient compliance with repeat endoscopic procedures.8

Conclusion

In conclusion, as in many fields of symptomatic treatment, endoscopy remains the first choice, either by using ERCP or EUS-guided procedures, after consideration of a multidisciplinary team with endoscopists, surgeons, and radiologists. However, what is crucial is establishing the right timing for surgery.

Author contributions

Andrada Seicean and Simona Vultur had substantial contributions to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data; drafting and critical revision of the article; and gave final approval of the version to be published. Both authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Bornman PC, Beckingham IJ. ABC of diseases of liver, pancreas, and biliary system. Chronic pancreatitis. BMJ. 2001;322(7287):660–663. | |

Bradley EL 3rd. Pancreatic duct pressure in chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1982;144(3):313–316. | |

Bhardwaj P, Garg PK, Maulik SK, Saraya A, Tandon RK, Acharya SK. A randomized controlled trial of antioxidant supplementation for pain relief in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):149–159. e2. | |

Karanjia ND, Widdison AL, Leung FW. Blood flow alterations in chronic pancreatitis: effects of secretory stimulation (abstract). Gastroenterology. 1990;98:A221. | |

Karanjia ND, Singh SM, Widdison AL, Lutrin FJ, Reber HA. Pancreatic ductal and interstitial pressures in cats with chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37(2):268–273. | |

Ahmed Ali U, Pahlplatz JM, Nealon WH, van Goor H, Gooszen HG, Boermeester MA. Endoscopic or surgical intervention for painful obstructive chronic pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD007884. | |

Díte P, Ruzicka M, Zboril V, Novotný I. A prospective, randomized trial comparing endoscopic and surgical therapy for chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2003;35(7):553–558. | |

Dumonceau JM, Delhaye M, Tringali A, et al. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2012;44(8):784–800. | |

Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Nio Y, et al. Endoscopic versus surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(7):676–684. | |

Cahen DL, Gouma DJ, Laramée P, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic vs surgical drainage of the pancreatic duct in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1690–1695. | |

Dumonceau JM, Costamagna G, Tringali A, et al. Treatment for painful calcified chronic pancreatitis: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy versus endoscopic treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2007;56(4):545–552. | |

Bagley FH, Braasch JW, Taylor RH, Warren KW. Sphincterotomy and sphincteroplasty in the treatment of pathologically mild chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1981;141(4):418–422. | |

Smits M, Rauws EA, Tytgat G, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic stones in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(6):556–560. | |

Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, Brandabur JJ, Traverso LW, Raltz S. Endoscopic pancreatic duct sphincterotomy: indication, technique and analysis of results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40(5):592–598. | |

Ell C, Rabenstein C, Schneider T, Ruppert T, Nicklas M, Bulling D. Safety and efficacy of pancreatic sphincterotomy in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(3):244–249. | |

Lévy P. Les traitements endoscopique de la douleur au cours de la pancreatite chronique sont-ils justifies? [Are endoscopic treatments of pain during chronic pancreatitis justified]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23(4):465–468. French. | |

Ueno N, Hashimoto M, Ozawa Y, Yoshizawa K. Treatment of pancreatic duct stones with the use of endoscopic balloon sphincter dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(3):309–310. | |

Carr-Locke DL. Endoscopy therapy of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(3 Pt 2):S77–S80. | |

Adamek HE, Jakobs R, Buttmann A, Adamek MU, Schneider AR, Riemann JF. Long term follow up of patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic stones treated with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Gut. 1999;45(3):402–405. | |

van der Hul R, Plaisier P, Jeekel J, Terpstra O, den Toom R, Bruining H. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy of pancreatic duct stones: immediate and long-term results. Endoscopy. 1994;26(7):573–578. | |

Costamagna G, Gabbrielli A, Mutignani M, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of pancreatic stones in chronic pancreatitis: immediate and medium-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(3):231–236. | |

Delhaye M, Van Steenbergen W, Cesmeli E, et al. Belgian consensus on chronic pancreatitis in adults and children: statements on diagnosis and nutritional, medical, and surgical treatment. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2014;77(1):47–65. | |

Howell DA, Dy RM, Hanson BL, Nezhad SF, Broaddus SB. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct stones using a 10F pancreatoscope and electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50(6):829–833. | |

Barthet M, Bernard JP, Duval JL, Affriat C, Sahel J. Biliary stenting in benign biliary stenosis complicating chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 1994;26(7):569–572. | |

Tandan M, Reddy DN, Talukdar R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy in painful chronic calcific pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(5):726–733. | |

Seven G, Schreiner MA, Ross AS, et al. Long-term outcomes associated with pancreatic extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for chronic calcific pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(5):997–1004. e1. | |

Guda NM, Partington S, Freeman ML. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in the management of chronic calcific pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. JOP. 2005;6(1):6–12. | |

Tandan M, Reddy DN, Santosh D, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and endotherapy for pancreatic calculi-a large single center experience. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29(4):143–148. | |

Choi EK, McHenry L, Watkins JL, et al. Use of intravenous secretin during extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy to facilitate endoscopic clearance of pancreatic duct stones. Pancreatology. 2012;12(3):272–275. | |

Tandan M, Reddy DN. Endotherapy in chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(37):6156–6164. | |

Ashby K, Lo SK. The role of pancreatic stenting in obstructive ductal disorders other than pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(4):306–311. | |

Farnbacher MJ, Mühldorfer S, Wehler M, Fischer B, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Interventional endoscopic therapy in chronic pancreatitis including temporary stenting: a definitive treatment? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(1):111–117. | |

Binmoeller KF, Jue P, Seifert H, Nam WC, Izbicki J, Soehendra N. Endoscopic pancreatic stent drainage in chronic pancreatitis and a dominant stricture: long-term results. Endoscopy. 1995;27(9):638–644. | |

Costamagna G, Bulajic M, Tringali A, et al. Multiple stenting of refractory pancreatic duct strictures in severe chronic pancreatitis: long-term results. Endoscopy. 2006;38(3):254–259. | |

Morgan DE, Smith JK, Hawkins K, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic stent therapy in advanced chronic pancreatitis: relationships between ductal changes, clinical response, and stent patency. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(4):821–826. | |

Seicean A, Burtin P, Boyer J, Pascu O. Traitement de la douleur dans la pancréatite chronique par la méthode endoscopique. [Treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis by an endoscopic method]. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2002;11(2):109–114. French. | |

Weber A, Schneider J, Neu B, et al. Endoscopic stent therapy in patients with chronic pancreatitis: a 5-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(5):715–720. | |

Sasahira N, Tada M, Isayama H, et al. Outcomes after clearance of pancreatic stones with or without pancreatic stenting. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(1):63–69. | |

Sauer B, Talreja J, Ellen K, Ku J, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Temporary placement of a fully covered self-expandable metal stent in the pancreatic duct for management of symptomatic refractory chronic pancreatitis: preliminary data (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(6):1173–1178. | |

Park do H, Kim MH, Moon SH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Feasibility and safety of placement of a newly designed, fully covered self-expandable metal stent for refractory benign pancreatic ductal strictures: a pilot study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(6):1182–1189. | |

Yang XJ, Lin Y, Zeng X, et al. A minimally invasive alternative for managing large pancreatic duct stones using a modified expandable metal mesh stent. Pancreatology. 2008;9(1–2):111–115. | |

Moon SH, Kim MH, Park do H, et al. Modified fully covered self-expandable metal stents with antimigration features for benign pancreatic-duct strictures in advanced chronic pancreatitis, with a focus on the safety profile and reducing migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(1):86–91. | |

Laukkarinen J, Lämsä T, Nordback I, Mikkonen J, Sand J. A novel biodegradable pancreatic stent for human pancreatic applications: a preclinical safety study in a large animal model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(7):1106–1112. | |

Farnbacher MJ, Voll R, Faissner R, et al. Composition of clogging material in pancreatic endoprostheses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(7):862–866. | |

Smits ME, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. The efficacy of endoscopic treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(3):202–207. | |

Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Verset G, Cremer M, Devière J. Long-term clinical outcome after endoscopic pancreatic ductal drainage for patients with painful chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(12):1096–1106. | |

Eleftheriadis N, Dinu F, Delhaye M, et al. Long-term outcome after pancreatic stenting in severe chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2005;37(3):223–230. | |

Farnbacher MJ, Radespiel-Tröger M, König MD, Wehler M, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Pancreatic endoprostheses in chronic pancreatitis: criteria to predict stent occlusion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(1):60–66. | |

Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38(3):341–346. | |

Ishihara T, Yamaguchi T, Seza K, Tadenuma H, Saisho H. Efficacy of s-type stents for the treatment of the main pancreatic duct stricture in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(6):744–750. | |

Sherman S, Hawes RH, Savides TJ, et al. Stent-induced pancreatic ductal and parenchimal changes: correlation of endoscopic ultrasound with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44(3):276–282. | |

Ponchon T, Bory RM, Hedelius F, et al. Endoscopic stenting for pain relief in chronic pancreatitis: results of a standardized protocol. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(5):452–456. | |

Tessier G, Bories E, Arvanitakis M, et al. EUS-guided pancreatogastrostomy and pancreatobulbostomy for the treatment of pain in patients with pancreatic ductal dilatation inaccessible for transpapilary endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(2):233–241. | |

Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, et al. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(1):56–64. | |

Kahaleh M, Hernandez AJ, Tokar J, Adams RB, Shami VM, Yeaton P. EUS-guided pancreaticogastrotomy: analysis of its efficacy to drain inaccessible pancreatic ducts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(2):224–230. | |

Will U, Fueldned F, Thieme AK, et al. Transgastric pancreatography and EUS-guided drainage of the pancreatic duct. J Hepatobil Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(4):377–382. | |

Mallery S, Matlock J, Freeman ML. EUS-guided rendez-vous drainage of obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts: report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(1):100–107. | |

Kamisawa T. Clinical significance of the minor duodenal papilla and accessory pancreatic duct. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39(7):605–615. | |

Gerke H, Byrne M, Stiffler HL, et al. Outcome of endoscopic minor papillotomy in patients symptomatic pancreas divisum. JOP. 2004;5(3):122–131. | |

Heyries L, Barthet M, Delvasto C, Zamora C, Bernard JP, Sahel J. Long-term results of endoscopic management of pancreas divisum with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(3):376–381. | |

Testoni PA. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stent placement for inflammatory pancreatic diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(45):5971–5978. | |

Gress F, Schmitt C, Sherman S, Ikenberry S, Lehman G. A prospective randomized comparison of endoscopic ultrasound- and computed tomography-guided celiac plexus block for managing chronic pancreatitis pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(4):900–905. | |

Leung JW, Bowen-Wright M, Aveling W, Shorvon PJ, Cotton PB. Coeliac plexus block for pain in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1983;70(12):730–732. | |

Michaels AJ, Draganov PV. Endoscopic ultrasonography guided celiac plexus neurolysis and celiac pleus block in the management of pain due to pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(26):3575–3580. | |

Levy M, Rajan E, Keeney G, Fletcher JG, Topazian M. Neural ganglia visualized by endoscopic ultrasound. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1787–1791. | |

LeBlanc JK, DeWitt J, Johnson C, et al. A prospective randomized trial of 1 versus 2 injections during EUS-guided celiac plexus block for chronic pancreatitis pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(4):835–842. | |

Santosh D, Lakhtakia S, Gupta R, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized trial comparing fluoroscopy guided percutaneous technique vs endoscopic ultrasound guided technique of coeliac plexus block for treatment of pain in chronic pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(9):979–984. | |

Sahai A, Lemelin V, Lam E, Paquin SC. Central vs bilateral endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block or neurolysis: a comparative study of short-term effectiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):326–329. | |

Sahai AJ, Wyse J. EUS-guided celiac plexus block for chronic pancreatitis: a placebo-controlled trial should be the first priority. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(2):430–431. | |

Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Wiersema MJ, et al. Initial evaluation of the efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided direct Ganglia neurolysis and block. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):98–103. | |

Gress F, Schmitt C, Sherman S, Ciaccia D, Ikenberry S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block for managing abdominal pain associated with chronic pancreatitis: a prospective single center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(2):409–416. | |

Kaufman M, Singh G, Das S, et al. Efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block and celiac plexus neurolysis for managing abdominal pain associated with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(2):127–134. | |

Puli SR, Reddy JB, Bechtold ML, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for pain due to chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer pain: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(11):2330–2337. | |

Basinski A, Stefaniak T, Vingerhoets A, et al. Effect of NCPB and VSPL on pain and quality of life in chronic pancreatitis patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(32):5010–5014. | |

Gunaratnam NT, Wong GY, Wiersema MJ. EUS-guided celiac plexus block for the management of pancreatic pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(Suppl 6):S28–S34. | |

Gress F, Ciaccia D, Kiel J, Sherman S, Lehman G. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided celiac plexus block (CB) for management of pain due to chronic pancreatitis (CP): a large single center experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45(4):AB173. | |

Loeve US, Mortensen MB. Lethal necrosis and perforation of the stomach and the aorta after multiple EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis procedures in a patient with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(1):151–152. | |

O’Toole TM, Schmulewitz N. Complications rate of EUS-guided celiac plexus blockade and neurolysis: results of a large case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41(7):593–597. | |

Warshaw AL, Rattner DW. Timing of surgical drainage for pancreatic pseudocyst. Clinical and chemical criteria. Ann Surg. 1985;202(6):720–724. | |

Krüger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, Meier PN. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abcesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(3):409–416. | |

Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, Vitton V, Desjeux A, Grimaud JC. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(2):245–252. | |

Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Conaway MR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst: a prospective comparison with conventional endoscopic drainage. Endoscopy. 2006;38(4):355–359. | |

Antillon MR, Shah RJ, Stiegmann G, Chen YK. Single-step EUS-guided transmural drainage of simple and complicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(6):797–803. | |

Cremer M, Devière J, Baize M, Matos C. New device for endoscopic cystoenterostomy. Endoscopy. 1990;22(2):76–77. | |

Fuchs M, Reimann FM, Gaebel C, Ludwig D, Stange EF. Treatment of infected pancreaticpseudocysts by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided cystogastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2000;32(8):654–657. | |

Cremer M, Deviere J, Enghelom L. Endoscopic management of cysts and pseudocysts in chronic pancreatitis: long-term follow-up after 7 years of experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35(1):1–9. | |

Bejanin H, Liguory C, Ink O, et al. Drainage endoscopique des pseudo-kystes du pancreas: etude de 26 cas. [Endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts of the pancreas. Study of 26 cases]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1993;17(11):804–810. French. | |

Dohmoto M, Rupp KD. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 1992;6(3):118–124. | |

Kozarek RA, Brayko CM, Harlan J, Sanowski RA, Cintora I, Kovac A. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31(5):322–327. | |

Beckingham IJ, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Long term outcome of endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(1):71–74. | |

Catalano MF, Geenen JE, Schmalz MJ, Johnson GK, Dean RS, Hogan WJ. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts with ductal communication by transpapillary pancreatic duct endoprosthesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(3):214–218. | |

Bhattacharya D, Ammori BJ. Minimally invasive approaches to the management of pancreatic pseudocysts: review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13(3):141–148. | |

Vosoghi M, Sial S, Garrett B, et al. EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage: review and experience at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. MedGenMed. 2002;4(3):2. | |

Barthet M, Bugallo M, Moreira LS, Bastid C, Sastre B, Sahel J. Management of cysts and pseudocysts complicating chronic pancreatitis. A retrospective study of 143 patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1993;17(4):270–276. | |

Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Walter A, Soehendra N. Transpapillary and transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(3):219–224. | |

Giovannini M, Bernardini D, Seitz JF. Cystogastrostomy entirely performed under endosonography guidance for pancreatic pseudocyst: results in six patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(2):200–203. | |

Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, Moutardier V, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33(6):473–477. | |

Sriram PV, Kaffes AJ, Rao GV, Reddy DN. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts complicated by portal hypertension or by intervening vessels. Endoscopy. 2005;37(3):231–235. | |

Nealon WH, Walser E. Surgical management of complications associated with percutaneous and/or endoscopic management of pseudocyst of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2005;241(6):948–957. | |

Voermans RP, Eisendrath P, Bruno MJ, Le Moine O, Devière J, Fockens P; ARCADE group. Initial evaluation of a novel prototype forward-viewing US endoscope in transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(5):1013–1017. | |

Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Le Moine O, Devière J. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: a comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(4):635–643. | |

Bang JY, Mel Wilcox C, Trevino JM, Ramesh J, Varadarajulu S. Relationship between stent characteristics and treatment outcomes in endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(Suppl 5):AB382. | |

Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Shah J, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75(4):870–876. | |

Téllez-Ávila FI, Villalobos-Garita A, Ramírez-Luna MÁ. Use of a novel covered self-expandable metal stent with an anti-migration system for endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of a pseudocyst. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5(6):297–299. | |

Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Tamhane A, Eloubeidi MA, Blakely J, Canon CL. Role of EUS in drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections not amenable for endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(6):1107–1119. | |

Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER, Wilcox CM. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(6):1102–1111. | |

Park DH, Lee SS, Moon SH, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural drainage for pancreatic pseudocysts: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41(10):842–848. | |

Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Sutton BS, Trevino JM, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Equal efficacy of endoscopic and surgical cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(3):583–590. e1. | |

Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Frequency of complications during EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in 148 consecutive patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(10):1504–1508. | |

Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, Caillol F, Giovannini M. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(4):524–529. | |

Kahl S, Zimmermann S, Genz I, et al. Risk factors for failure of endoscopic stenting of biliary strictures in chronic pancreatitis: a prospective follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(11):2448–2453. | |

Catalano MF, Linder JD, George S, Alcocer E, Geenen JE. Treatment of symptomatic distal common bile duct stenosis secondary to chronic pancreatitis: comparison of single vs multiple simultaneous stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(6):945–952. | |

Cahen DL, Rauws EA, Gouma DJ, Fockens P, Bruno MJ. Removable fully covered self-expandable metal stents in the treatment of common bile duct strictures due to chronic pancreatitis: a case series. Endoscopy. 2008;40(8):697–700. | |

Behm B, Brock A, Clarke BW, et al. Partially covered self-expandable metallic stents for benign biliary strictures due to chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41(6):547–551. | |

Devière J, Nageshwar Reddy D, Püspök A, et al; Benign Biliary Stenoses Working Group. Successful management of benign biliary strictures with fully covered self-expanding metal stents. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):385–395; quiz e15. | |

Sherman S, Lehman GA, Hawes RH, et al. Pancreatic ductal stones: frequency of successful endoscopic removal and improvement in symptoms. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(5):511–517. | |

Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Le Moine O, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic drainage in chronic pancreatitis associated with ductal stones: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(6):547–555. | |

Sauerbruch T, Holl J, Sackmann M, Paumgartner G. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of pancreatic stones. Gut. 1989;30(10):1406–1411. | |

Ohara H, Hoshino M, Hayakawa T, et al. Single application extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is the first choice for patients with pancreatic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(7):1388–1394. | |

Delhaye M, Vandermeeren A, Baize M, Cremer M. Extracorporeal wave-shock lithotripsy of pancreatic calculi. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(2):610–620. | |

Schneider HT, May A, Benninger J, et al. Piezoelectric shock wave lithotripsy of pancreatic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(11):2042–2048. | |

Choi KS, Kim MH, Lee YS, et al. [Disintegration of pancreatic duct stones with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46(5):396–403. Korean. | |

Sauerbruch T, Holl J, Sackmann M, Paumgartner G. Extracorporeal lithotripsy of pancreatic stones in patients with chronic pancreatitis and pain: a prospective follow-up study. Gut. 1992;33(7):969–972. | |

Inui K, Tazuma S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Treatment of pancreatic stones with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: results of a multicenter survey. Pancreas. 2005;30(1):26–30. | |

Tadenuma H, Ishihara T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Long-term results of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and endoscopic therapy for pancreatic stones. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(11):1128–1135. | |

Cremer M, Devière J, Delhaye M, Baize M, Vandermeeren A. Stenting in severe chronic pancreatitis: results of medium-term follow-up in seventy-six patients. Endoscopy. 1991;23(3):171–176. | |

Rösch T, Daniel S, Scholz M, et al; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Research Group. Endoscopic treatment of chronic pancreatitis: a multicenter study of 1000 patients with long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2002;34(10):765–771. | |

Weber A, Schneider J, Neu B, et al. Endoscopic stent therapy for patients with chronic pancreatitis: results from a prospective follow-up study. Pancreas. 2007;34(3):287–294. | |

Devière J, Devaere S, Baize M, Cremer M. Endoscopic biliary drainage in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36(2):96–100. | |

Smits ME, Rauws EA, Gulik TM. Long-term results of endoscopic stenting and surgical drainage for biliary stricture due to chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1996;83(6):764–768. | |

Born P, Rosch T, Bruhl K, et al. Long-term results ofendoscopic treatment of biliary duct obstruction due to pancreatic disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45(21):833–839. | |

Kiehne K, Fölsch UR, Nitsche R. High complication rate of bile duct stents in patients with chronic alcohol pancreatitis due to noncompliance. Endoscopy. 2000;32(5):377–380. | |

Vitale GC, Reed DN Jr, Nguyen CT, Lawhon JC, Larson GM. Endoscopic treatment of distal bile duct stricture from chronic pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(3):227–231. | |

Farnbacher MJ, Rabenstein T, Ell C, Hahn EG, Schneider HT. Is endoscopic drainage of common bile duct stenoses in chronic pancreatitis up-to-date? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(6):1466–1471. | |

Cahen DL, van Berkel AM, Oskam D, et al. Long-term results of endoscopic drainage of common bile duct strictures in chronic pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17(1):103–108. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.