Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 9

Effects of aural stimulation with capsaicin ointment on swallowing function in elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia

Authors Kondo E, Jinnouchi O , Ohnishi H, Kawata I, Nakano S, Goda M, Kitamura Y, Abe K, Hoshikawa H, Okamoto H, Takeda N

Received 12 May 2014

Accepted for publication 16 June 2014

Published 1 October 2014 Volume 2014:9 Pages 1661—1667

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S67602

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Eiji Kondo,1,2 Osamu Jinnouchi,3 Hiroki Ohnishi,3 Ikuji Kawata,3 Seiichi Nakano,2 Masakazu Goda,1 Yoshiaki Kitamura,1 Koji Abe,1 Hiroshi Hoshikawa,4 Hidehiko Okamoto,5 Noriaki Takeda1

1Department of Otolaryngology, University of Tokushima School of Medicine, Tokushima, Japan; 2Department of Otolaryngology, Kochi National Hospital, Kochi, Japan; 3Department of Otolaryngology, Anan Kyoei Hospital, Anan, Japan; 4Department of Otolaryngology, Kagawa University School of Medicine, Kagawa, Japan; 5Department of Sensori-Motor Integration, National Institute for Physiological Sciences, Okazaki, Japan

Objective: In the present study, an attempt was made to examine the effects of aural stimulation with ointment containing capsaicin on swallowing function in order to develop a novel and safe treatment for non-obstructive dysphagia in elderly patients.

Design: A prospective pilot, non-blinded, non-controlled study with case series evaluating a new treatment.

Setting: Secondary hospitals.

Patients and methods: The present study included 26 elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Ointment containing 0.025% capsaicin (0.5 g) was applied to the external auditory canal with a cotton swab under otoscope only once or once a day for 7 days before swallowing of a bolus of colored water (3 mL), which was recorded by transnasal videoendoscopy and evaluated according to the endoscopic swallowing score.

Results: After a single application of 0.025% capsaicin ointment to the right external auditory canal, the endoscopic swallowing score was significantly decreased, and this effect lasted for 60 minutes. After repeated applications of the ointment to each external auditory canal alternatively once a day for 7 days, the endoscopic swallowing score decreased significantly in patients with more severe non-obstructive dysphagia. Of the eight tube-fed patients of this group, three began direct swallowing exercises using jelly, which subsequently restored their oral food intake.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that stimulation of the external auditory canal with ointment containing capsaicin improves swallowing function in elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. By the same mechanism used by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors to induce cough reflex, which has been shown to prevent aspiration pneumonia, aural stimulation with capsaicin may reduce the incidence of aspiration pneumonia in dysphagia patients via Arnold’s ear-cough reflex stimulation.

Keywords: swallowing reflex, Arnold’s ear-cough reflex, external auditory canal, oral food intake

Introduction

Pneumonia is a major cause of death in the elderly, and its dominant form is aspiration pneumonia, the predisposing factor of which is dysphagia, an impairment of swallowing. The prevalence of dysphagia is estimated to range from 16%–22% among individuals aged 50 years or over and is increased to 20%–40% among patients with stroke and Parkinson’s disease.1,2 However, the efficacy of rehabilitative and compensatory methods for the treatment of dysphagia has not been established.3 Dysphagia develops in the elderly as a result of age-related changes in swallowing physiology or neurogenic disease, the incidence of which increases with aging, or both. Among neurological diseases or complications, stroke and dementia reflect high rates of both dysphagia and pneumonia.4

Cough and swallowing reflexes are important airway protective mechanisms against aspiration. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, a side effect of which is cough,5 were reported to reduce the incidence of aspiration pneumonia in hypertensive patients with stroke.6 ACE inhibitors also have been reported to prevent pneumonia in post-stroke patients7–10 by their ability to improve swallowing function.11 On the other hand, the auricular branch of the vagus, the Arnold’s nerve, is distributed to the external auditory canal and its stimulation triggers the cough reflex.12 The Arnold’s ear–cough reflex is frequently triggered by otolaryngologists during manipulations of the external auditory canal such as ear syringing.13 Capsaicin, an agonist of transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1), has been shown to activate peripheral sensory C-fibers.14 It was reported that stimulation of the sensory C-fiber branches of the vagus in the laryngotracheal mucosa with capsaicin induces the cough reflex.15 Also, it was demonstrated that stimulation of capsaicin-sensitive sensory C-fibers in the pharyngolaryngeal mucosa elicits the swallowing reflex.16 Taken together, these findings led to the hypothesis that enhancement of the cough reflex by simulation of auricular sensory C-fiber branches of the vagus with capsaicin ointment improves the swallowing reflex in dysphagic patients in the same way that ACE inhibitors do.

The aim of the present study was, thus, to examine the effects of aural stimulation with capsaicin ointment on swallowing function in order to develop a novel and safe treatment for non-obstructive dysphagia in elderly patients. For that purpose, we used transnasal videoendoscopy and swallowing scoring17 to record and evaluate the changes in patients’ swallowing function after a single or repetitive administration of capsaicin ointment to the external auditory canal.

Methods

Subjects

The present study was a prospective pilot study. It was conducted in three experiments in two secondary hospitals and enrolled 26 elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia distributed as follows: Experiment 1: ten outpatients (eight males and two females; 64–87 years old; mean age: 79.3±7.9 years) with non-obstructive dysphagia and an average endoscopic swallowing score (AESS) of 4.5±1.4; Experiment 2: six outpatients (five males and one female; 66–86 years old; mean age: 80.7±7.4 years; AESS: 6.7±0.8); and Experiment 3: ten inpatients (nine males and one female; 74–90 years old; mean age: 81.3±5.0 years; AESS: 6.5±1.6; Table 1).

In Experiments 1 and 2, we examined consecutive Japanese elderly outpatients with non-obstructive dysphagia who complained of choking upon swallowing water or food at secondary hospitals in Tokushima and Kochi, Japan. The patients had no obstructive lesion in the pharyngolarynx as confirmed by endoscopy. Their characteristics are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| Table 3 Characteristics of patients in Experiment 2 (n=6) |

In Experiment 3, we examined consecutive Japanese elderly inpatients with non-obstructive dysphagia who received long-term care for their physical disability or mental deterioration that varied from moderate cognitive impairment to dementia in the nursing care ward of a secondary hospital in Tokushima, Japan. The patients had no obstructive lesion in the pharyngolarynx as confirmed by endoscopy. Their characteristics are shown in Table 4. Their physical symptoms and cognitive impairment had been stable for the preceding 1 month. Among the ten inpatients in Experiment 3, eight were tube-fed due to aspiration pneumonia and underwent indirect, but not direct swallowing exercises under the guidance of speech therapists. The remaining two inpatients ingested a modified diet orally with the help of speech therapists.

This study was approved by the Committee for Medical Ethics of Tokushima University Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the study.

Ointment containing 0.025% capsaicin

Based on the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (16th edition) published by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, ointment containing 0.025% capsaicin was prepared according to the protocol of Japanese Drug Preparation of Hospital Pharmacy (4th edition) as follows: 25 mg of capsaicin (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 500 μL of 100% ethanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and the solution was then mixed with 100 g hydrophilic ointment. Under the otoscope, 0.5 g of ointment containing 0.025% capsaicin was applied to the external auditory canal with a cotton swab by an otolaryngologist. In patients in Experiment 1, swallowing was evaluated by transnasal videoendoscopy 5 minutes after a single application of 0.025% capsaicin ointment to the right external auditory canal. In those in Experiment 2, transnasal videoendoscopy was performed 5, 30, and 60 minutes after a single application of ointment containing capsaicin to the right external auditory canal. After confirming that no adverse event occurred in Experiments 1 and 2, repeated applications of the capsaicin ointment were performed in Experiment 3, in which more severe non-obstructive dysphagic patients participated. Also, in patients in Experiment 3, swallowing was evaluated 7 days after repeated daily applications of the same ointment to each external auditory canal alternatively.

Videoendoscopy

The standard protocol of videoendoscopic evaluation of swallowing proposed by the Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Society of Japan was used.18 Accordingly, patients were seated facing an otolaryngologist. Water was dyed with blue food coloring for ease of visualization and given to the patient in a bolus of 3 mL. Swallowing of the colored water was recorded by the video rhinolaryngoscope system with a flexible fiber optic endoscope of 3.1 mm diameter (VNL-100S®; Pentax, Tokyo, Japan). The video images of swallowing were evaluated by another otolaryngologist blinded to clinical data and independent from the examiner.

Evaluation of swallowing function with the endoscopic swallowing scoring

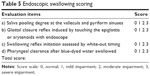

Endoscopic swallowing scoring evaluates the function of swallowing based on videoendoscopy (Table 5).17 The full score is 12, and a score of more than 7 indicates a serious risk for aspiration. Scores over 10 indicate oral feeding difficulty. The endoscopic swallowing scoring consists of four swallowing components: a) saliva pooling degree at the vallecula and pyriform sinuses, b) the glottal closure reflex induced by touching the epiglottis or arytenoid with the endoscope, c) swallowing reflex initiation assessed by white-out timing, and d) pharyngeal clearance after blue-dyed water was swallowed. Each item was scored on a scale of 0 to 3, where 0 is normal, 1 is mild impairment, 2 is moderate impairment, and 3 is severe. The total score was used as an index of swallowing function.

| Table 5 Endoscopic swallowing scoring |

Statistics

Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Friedman test with Shirley–Williams post hoc test were used for statistical analysis, and P≤0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In Experiment 1, endoscopic swallowing scores were 4.5±1.4 (mean ± standard deviation) in elderly outpatients with nonobstructive dysphagia. Five minutes after a single application of 0.025% capsaicin ointment to the right external auditory canal, swallowing scores were significantly decreased to 3.0±1.9 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test: P=0.017; Figure 1). In Experiment 2, endoscopic swallowing scores were 6.7±0.8 in other elderly outpatients with non-obstructive dysphagia. A single application of the capsaicin ointment to the right external auditory canal also significantly decreased the score to 5.2±0.8 at 5 minutes, and the effects lasted for about 60 minutes (Friedman test: P=0.003; with Shirley–Williams post hoc test: P=0.05; Figure 2).

In Experiment 3, endoscopic swallowing scores were 6.5±1.6 in elderly inpatients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Five minutes after the first application of the ointment to the right external auditory canal, no changes in endoscopic swallowing scores were noticed on day 1. However, after repeated applications of capsaicin ointment to each external auditory canal alternatively once a day for 7 days, endoscopic swallowing scores were significantly decreased to 5.2±0.9 in elderly inpatients with non-obstructive dysphagia (Friedman test: P=0.028; with Shirley–Williams post hoc test: P=0.05; Figure 3). Among ten inpatients, eight were fed by nasogastric tubes due to aspiration pneumonia, and after repeated applications of the capsaicin ointment to each external auditory canal for 7 days, six inpatients began direct swallowing exercises with a small amount of jelly given by speech therapists. Ultimately, three inpatients could ingest orally a diet modified with cornstarch three times a day.

No adverse effects including otalgia, otitis externa, myringitis, temporomandibular joint dysfunction and facial palsy were induced in any experiment, but the application of the capsaicin ointment evoked a warm sensation in the external auditory canal in almost all patients.

Discussion

In Experiments 1 and 2 of the present study, the stimulation of the external auditory canal with 0.025% capsaicin ointment improved the endoscopic swallowing score significantly in elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia, and this effect lasted for at least 60 minutes. The superior laryngeal branch of the vagus is distributed to the pharyngolaryngeal mucosa, and capsaicin, an agonist of TRPV1, is known to activate vagal C-fibers.14 It was reported that in post-stroke patients, the injection of 10−9 to 10−11 M capsaicin solution in the pharynx improved the delay in swallowing reflex.19 Moreover, administration of a pastille containing capsaicin was also reported to improve the delay in swallowing reflex in elderly dysphagic patients.20 These previous findings suggest that the entopic sensory vagal stimulation of the pharynx with capsaicin improves the swallowing reflex in patients with dysphagia. The present findings suggest that the ectopic stimulation of the Arnold’s branch of the vagus in the external auditory canal with capsaicin also improves the swallowing reflex in elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Aural stimulation with capsaicin represents a novel treatment for non-obstructive dysphagia and it is safer than capsaicin injection or pastille, because patients are not required to swallow anything.

In Experiment 3, a single stimulation of the external auditory canal with 0.025% capsaicin ointment did not change the endoscopic swallowing score in elderly inpatients with non-obstructive dysphagia. However, repeated aural stimulation with the ointment at the same concentration once a day for 7 days improved the endoscopic swallowing score. These findings suggest that repeated aural stimulation with capsaicin at a dose of 0.025% for 1 week, rather than a single application, is needed to improve the swallowing function in elderly patients with more severe non-obstructive dysphagia.

Patients with aspiration pneumonia showed impaired cough and swallowing reflexes, which are airway protective mechanisms against aspiration.6 Because substance P (SP) is the neurotransmitter that plays an important role in both cough and swallowing reflexes,19,21 improvements in cough and swallowing reflexes are expected to be related to elevation of SP. ACE inhibitors were reported to reduce the incidence of aspiration pneumonia in hypertensive patients with stroke,22 because ACE inhibitors not only induce the cough reflex5 but also improve the delay in the swallowing reflex.11 Because ACE, an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II also degrades SP, ACE inhibitors are considered to induce the accumulation of SP in the pharyngolaryngeal and tracheal submucosa, resulting in the enhancement of the cough and swallowing reflexes. On the other hand, when the vagal C-fibers in the pharyngolarynx and trachea are stimulated by capsaicin, afferent inputs are transmitted to the nucleus of the solitary tract with SP, leading to the cough reflex.15 At the same time, the axon collateral reflex also induces both entopic and ectopic antidromic release of SP in the pharyngolaryngeal and tracheal submucosa.23 Therefore, it is suggested that the aural stimulation of vagal C-fibers with capsaicin induces ectopic antidromic release of SP in the pharyngolaryngeal submucosa through the axon reflex, leading to an improvement in the swallowing reflex in patients with dysphagia via Arnold’s cough reflex. Because ACE inhibitors enhance the cough and swallowing reflexes by elevation of SP to prevent aspiration pneumonia, it is also suggested that aural stimulation with capsaicin could reduce the incidence of pneumonia in patients with dysphagia.

Alternatively, there is another possibility that the aural stimulation of sensory C-fibers of the vagus with capsaicin activates the central nervous system that is related to cough and swallowing reflexes. It was reported that trigeminal stimulation with intensive oral care improved the sensitivity of the cough reflex in elderly nursing care patients.24 It was also reported that gustatory and trigeminal stimulation of the oral cavity with citric acid improved the swallowing reflex in nursing home residents with neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia.25

The possibility that mechanical stimulation of the external auditory canal with a cotton swab rather than chemical aural stimulation of capsaicin improves the swallowing reflex in dysphagic patients cannot be excluded. A double-blind study to compare the effects of ointment containing capsaicin to those of placebo ointment was needed, but such a control experiment was not conducted in the present study. This was because patients perceive a warm sensation in the external auditory canal induced by the capsaicin ointment, and examiners must follow the degree of warmth in order to prevent adverse reactions to capsaicin.

In Experiment 3, three of eight tube-fed patients began ingesting a modified diet orally three times a day after direct swallowing exercises using jelly, preceded by repeated applications of capsaicin to external auditory canal. This finding suggests that repeated aural stimulation of the external auditory canal with capsaicin is a useful method to pave the way for direct swallowing exercises in tube-fed patients with non-obstructive dysphagia for restoration of oral feeding.

Although capsaicin initially stimulates unmyelinated sensory nerves through TRPV1, chronic exposure to a high-dose of capsaicin causes their long-term functional impairment due to desensitization of TRPV1 and depletion of neuropeptides such as SP (capsaicin defunctionalization).26 However, in the present study, it is suggested that repeated applications of a low dose of capsaicin ointment (0.025%) to each external auditory canal alternatively once a day does not defunctionalize the Arnold’s branches of the vagus in patients with dysphagia.

There are some limitations of the present study. It was non-blinded, and the sample size was small. The scoring system is subjective. There was no blinding of scorers to avoid bias or double-marking for reliability. The possibility that the aural mechanical stimulation with a cotton swab improves the swallowing reflex in patients with dysphagia cannot be excluded. The aural stimulation with capsaicin ointment is not useful in patients with obstructive dysphagia.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the stimulation of the external auditory canal with capsaicin improved swallowing function in elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Although entopic sensory vagal stimulation in the pharynx with capsaicin was reported to improve swallowing reflex, the present study suggests that ectopic stimulation of the Arnold’s branch of the vagus in the external auditory canal with capsaicin also improves the swallowing reflex in a safer manner. Because ACE inhibitors that induce the cough reflex also reduce the incidence of pneumonia, it is possible that topical application of ointment containing capsaicin to the external auditory canal reduces the incidence of aspiration pneumonia via the Arnold-cough reflex in elderly patients with non-obstructive dysphagia. Once-a-day application of ointment containing 0.025% capsaicin to each external auditory canal alternatively did not seem to induce capsaicin defunctionalization, which may indicate a reduced ability to stimulate sensory nerves.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Professor Bukasa Kalubi for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Lindgren S, Janzon L. Prevalence of swallowing complaints and clinical findings among 50–79-year-old men and women in an urban population. Dysphagia. 1991;6(4):187–192. | ||

Gordon C, Hewer RL, Wade DT. Dysphagia in acute stroke. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987;295(6596):411–414. | ||

Antunes EB, Lunet N. Effects of the head lift exercise on the swallow function: a systematic review. Gerodontology. 2012;29(4):247–257. | ||

Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby G, Crary MA. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7: 287–298. | ||

Israili ZH, Hall WD. Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. A review of the literature and pathophysiology. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(3):234–242. | ||

Ebihara S, Ebihara T, Kohzuki M. Effect of aging on cough and swallowing reflexes: implications for preventing aspiration pneumonia. Lung. 2012;190(1):29–33. | ||

Sekizawa K, Matsui T, Nakagawa T, Nakayama K, Sasaki H. ACE inhibitors and pneumonia. Lancet. 1998;352(9133):1069. | ||

Arai T, Yasuda Y, Toshima S, Yoshimi N, Kashiki Y. ACE inhibitors and pneumonia in elderly people. Lancet. 1998;352(9144):1937–1938. | ||

Arai T, Yoshimi N, Fujiwara H, Sekizawa K. Serum substance P concentrations and silent aspiration in elderly patients with stroke. Neurology. 2003;61(11):1625–1626. | ||

Ohkubo T, Chapman N, Neal B, Woodward M, Omae T, Chalmers J. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-based regimen on pneumonia risk. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 169(9):1041–1045. | ||

Nakayama K, Sekizawa K, Sasaki H. ACE inhibitor and swallowing reflex. Chest. 1998;113(5):1425. | ||

Gupta D, Verma S, Vishwakarma SK. Anatomic basis of Arnold’s ear-cough reflex. Surg Radiol Anat. 1986;8(4):217–220. | ||

Bloustine S, Langston L, Miller T. Ear-cough (Arnold’s) reflex. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1976;85(3 pt 1):406–407. | ||

Wong GY, Gavva NR. Therapeutic potential of vanilloid receptor TRPV1 agonists and antagonists as analgesics: recent advances and setbacks. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(1):267–277. | ||

Canning BJ. Afferent nerves regulating the cough reflex: mechanisms and mediators of cough in disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010; 43(1):15–25. | ||

Jin Y, Sekizawa K, Fukushima T, Morikawa M, Nakazawa H, Sasaki H. Capsaicin desensitization inhibits swallowing reflex in guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(1):261–263. | ||

Hyodo M, Nishikubo K, Hirose K. [New scoring proposed for endoscopic evaluation and clinical significance]. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho (Tokyo). 2010;113(8):670–678. Japanese. | ||

Committee on Dysphagia of the Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Society of Japan: Practice Guidelines for Dysphagia. Kyoto: Kanehara Shuppan; 2008. | ||

Ebihara T, Sekizawa K, Nakazawa H, Sasaki H. Capsaicin and swallowing reflex. Lancet. 1993;341(8842):432. | ||

Ebihara T, Takahashi H, Ebihara S, et al. Capsaicin troche for swallowing dysfunction in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):824–828. | ||

Sekizawa K, Jia YX, Ebihara T, Hirose Y, Hirayama Y, Sasaki H. Role of substance P in cough. Pulm Pharmacol. 1996;9(5–6):323–328. | ||

Shinohara Y, Origasa H. Post-stroke pneumonia prevention by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: results of a meta-analysis of five studies in Asians. Adv Ther. 2012;29(10):900–912. | ||

Pisi G, Olivieri D, Chetta A. The airway neurogenic inflammation: clinical and pharmacological implications. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;8(3):176–181. | ||

Watando A, Ebihara S, Ebihara T, et al. Daily oral care and cough reflex sensitivity in elderly nursing home patients. Chest. 2004;126(4): 1066–1070. | ||

Pelletier CA, Lawless HT. Effect of citric acid and citric acid-sucrose mixtures on swallowing in neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2003;18(4):231–241. | ||

Anand P, Bley K. Topical capsaicin for pain management: therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action of the new high-concentration capsaicin 8% patch. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(4):490–502. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.