Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 14

Dissociative states in borderline personality disorder and their relationships to psychotropic medication

Authors Pec O , Bob P , Simek J , Raboch J

Received 4 July 2018

Accepted for publication 24 September 2018

Published 23 November 2018 Volume 2018:14 Pages 3253—3257

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S179091

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Ondrej Pec,1,2 Petr Bob,1,3 Jakub Simek,1 Jiri Raboch1

1Center for Neuropsychiatric Research of Traumatic Stress, Department of Psychiatry and UHSL, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; 2Psychotherapeutic and Psychosomatic Clinic ESET, Prague, Czech Republic; 3Central European Institute of Technology, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Background: According to recent data, dissociation may play an important role in borderline personality disorder (BPD), nevertheless specific influences of psychotropic medication on dissociative symptoms in BPD and their therapeutic indications are largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to assess relationships of dissociative symptoms in BPD patients with levels of psychotropic medication and compare these results with a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia.

Materials and methods: In this study, we investigated 52 BPD patients and compared the results with a control group of 36 schizophrenia patients. In all participants, we assessed actual day doses of antipsychotic medication in chlorpromazine equivalents and antidepressant medication in fluoxetine equivalents. Dissociative symptoms were measured by Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), and other psychopathological symptoms were measured using Health of the Nation Outcome Scales.

Results: Results indicate that dissociative symptoms measured by DES were significantly correlated with antipsychotic medication (Spearman R=0.45, P<0.01) in chlorpromazine equivalents and antidepressant medication in fluoxetine equivalents (0.36, P<0.01). These relationships between medication and dissociative symptoms were not found in the control group of schizophrenia patients.

Conclusion: The results suggest that levels of antipsychotic medication and antidepressant medication are significantly associated with dissociative symptoms in BPD but not in schizophrenia.

Keywords: dissociation, stress, antipsychotics, antidepressants

Introduction

Dissociation describes mental disintegration related to stress influences,1–4 which leads to alterations of neural activity that may dissociate certain external and internal information out of awareness leading to states of divided consciousness.1,5–8 In this context, dissociation also reflects a cognitive conflict related to implicitly consolidated traumatic memories.2,6 The process of mental disintegration and conflicting information processing according to recent findings is likely closely associated with activity of anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) that is related to detecting a cognitive conflict and selection among competing stimuli.1,9,10 Dissociative processes were also reported to have a significant role in borderline personality disorder (BPD) and other mental diseases, for example, in schizophrenia.11–14 Because of high prevalence of dissociative symptoms in schizophrenia and psychotic-like symptoms in BPD, these disorders have significant similarities that may help to understand manifestations of dissociative symptoms and their relationship to medication.12–14

Recent findings indicate that treatment influences of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication are closely linked to ACC activity,15–20 which significantly influences mechanisms of conscious awareness and processing conflicting information.21–23 With the aim to study relationships between dissociative symptoms and antipsychotic and antidepressant medication, we compared occurrence of dissociation in BPD and the control group of schizophrenia patients, and its association with chlorpromazine equivalents of antipsychotic and fluoxetine equivalents of antidepressant medication.

Materials and methods

Participants

The participants were recruited from regular daily treatment programs at the Psychotherapeutic and Psychosomatic Clinic ESET in Prague. The participants had diagnosis of BPD and the control group of patients had diagnosis of schizophrenia. Exclusion criteria were organic illnesses involving the central nervous system, substance, and/or alcohol abuse and mental retardation (IQ Raven lower than 90).24 Clinical diagnoses were based on DSM-IV criteria. Diagnosis of BPD patients was confirmed using semi-structured interview for BPD SCID-II25 and diagnosis of schizophrenia patients was reassessed using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.26 For all participants, we calculated actual day doses of antipsychotic medication in equivalents of chlorpromazine (EC) and antidepressant medication in equivalents of fluoxetine (EF).27–29 The clinical study was approved by Charles University Hospital ethical committee, and all participants provided written informed consent in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

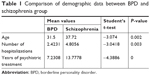

The sample included 52 patients with BPD (14 men and 38 women), mean age 31.5 years; SD=8.6 years; mean period of psychiatric treatment 7.23 years (SD=5.36 years) with average of 2.4 hospitalizations. The control group of schizophrenia patients included 36 participants (18 men and 18 women), mean age 37.7 years; SD=10.32 years, mean period of psychiatric treatment 13.78 years; SD=8.63 years with average of 4.81 hospitalizations.

Psychometric measures

Dissociative symptoms were assessed using Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES).30,31 DES is a 28-item self-reported questionnaire that evaluates frequencies of various experiences of dissociative phenomena in everyday life. Each item ranges from 0 to 100, and the mean of all item scores is calculated as the DES score. In the present study, we used the Czech version of the DES that similarly as original English version displays high reliability and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.92, test–retest reliability after week 0.91).32,33

Psychotic manifestations in both groups of patients were measured using Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS).34 The scale includes 12 items (overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behavior; non-accidental self-injury; problem drinking or drug-taking; cognitive problems; physical illness or disability problems; problems with hallucinations or delusions; problems with depressed mood; other mental and behavioral problems; problems with relationships; problems with activities of daily living; problems with living conditions; problems with occupation and activities). The assessment includes external evaluation by a mental health professional and the self-reported version for patients. The scale was translated into the Czech language (Cronbach’s alpha 0.797, test–retest reliability after one week 0.85).35

Data analysis

Statistical evaluation of psychometric measures and doses of psychotropic medication included descriptive statistics and Spearman correlation coefficients. The non-parametric analyses were preferred because DES data did not have normal distribution. All the methods of statistical evaluation were performed using the software package Statistica version 6.

Results

Results show statistically significant correlations of dissociative symptoms measured by DES with the levels of antipsychotic medication (EC) (Spearman R=0.45; P=0.0007 refined Fisher Z=0.51), and with the levels of antidepressant medication (EF) (Spearman R=0.36; P=0.008 refined Fisher Z=0.50) in patients with BPD (Figure 1) but not in schizophrenia patients (for EC Spearman R=0.19; P>0.05, for EF Spearman R=0.07; P>0.05). The results also did not show statistically significant correlations between psychotropic medication and psychotic symptoms measured by HoNOS (for BPD group – EC Spearman R=0.10; P>0.05, EF Spearman R=0.19; P>0.05; for the schizophrenia group – EC Spearman R=0.28; P>0.05, EF Spearman R=–0.28; P>0.05). For the BPD group, we also calculated correlations: between EC and the HoNOS item “problems with hallucinations or delusions” (Spearman R=0.007; P>0.05); between EF and the item of HoNOS “problems with depressed mood” (Spearman R=0.18; P>0.05); and between EC or EF and items “overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behavior” or “non-accidental self-injury” (EC: Spearman R=−0.06, resp. 0.12; EF: Spearman R=0.05, resp. 0.21, P>0.05 in all cases).

In the BPD sample, 20 patients (38%) had other co-occurring clinical diagnoses, apart from BPD: four patients (8%) had one other personality disorder, one patient (2%) had more than one other personality disorder, two patients (4%) had gender identity disorder, six patients (12%) had affective disorder, seven patients (13%) had neurotic disorder, and three patients (6%) had eating disorder. In the schizophrenia group, there were only two patients (6%) with co-occurring clinical diagnoses (eating disorder), apart from schizophrenia.

The comparisons of demographic data between the samples are presented in Table 1. For detailed between-group comparisons, please see Tables 2–4.

| Table 1 Comparison of demographic data between BPD and schizophrenia group |

Discussion

The results indicate significant correlations between dissociative symptoms measured by DES and doses of antipsychotics and antidepressant medication in BPD. This relationship between medication and dissociative symptoms may be linked to a specific and very important role of stress in BPD. These results suggest that dissociative states represent more significant factor in BPD etiology than in schizophrenia.4,14,36,37

Recent findings indicate that antipsychotic and antidepressant treatment decreases activation of ACC.15–20,38 On the other hand, increased ACC activity is also linked to a detection of cognitive conflict.39–41 These data suggest a hypothesis for further research that decreased ACC activity due to antipsychotic and antidepressant medication in BPD may also decrease conscious awareness of conflicting stressful experiences, which may produce dissociative symptoms measured by DES.

The results also show that dissociative symptoms correlate with the medication equivalents (EC, EF) just in the BPD group but not in the schizophrenia group. Because the patients’ medications were prescribed without a previous knowledge about the level of dissociative symptoms, these results also suggest important hypothesis for further research.

Nevertheless, these results simply may mean that prescribed higher doses of medication do not reflect clinical assessment of symptoms. Consequently, preliminary judgments about relationships between dissociative symptom and assessed medication equivalents can be made. These implications might be reasonable because these correlations between DES and medication were found only in BPD. On the other hand in schizophrenia patients, dissociative and other psychopathological symptoms did not correlate with medication. This finding suggests another hypothesis that the relationship between DES and medication likely does not reflect simple relationship “higher symptoms, higher medication” as usually may be expected. Certain limitations of this study need to be taken into account, it means mainly relatively small sample sizes that may cause a selection bias of patients regarding their comorbidities and polypharmacy effects. Nevertheless, it can be hypothesized that borderline and schizophrenic patients may differ with respect to side effects of psychotropic medication and that dissociative symptoms in BPD can be partially influenced by an iatrogenic effect of pharmacotherapy, especially polypharmacy in BPD and in BPD. Another possible hypothesis is that pharmacotherapy is more helpful for dissociative symptoms in schizophrenia than in BPD. In longitudinal research we plan to continue this research and we expect that certain issues regarding alternative hypotheses and research limitations might be resolved and will enable clinical applications of these findings.

Conclusion

These results are in agreement with recent recommendations for BPD treatment focusing mainly on psychological therapies and state that no psychotropic drug has a specific marketing authorization for the treatment in BPD.42–45 The results also emphasize rigorous diagnostic distinctions of BPD, affective disorders, and schizophrenia.46–49 In this context, the results are in agreement with findings indicating an important role of dissociative processes in BPD, which might be hypothetically linked with antipsychotic and antidepressant medication.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Charles University projects Progress, SVV for support of this research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Bob P. Pain, dissociation and subliminal self-representations. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17(1):355–369. | ||

Bob P. Dissociation, epileptiform discharges and chaos in the brain: Toward a neuroscientific theory of dissociation. Act Nerv Super. 2012;54(3–4):84–107. | ||

Breuer J, Freud S. Studies in hysteria. New York: Basic Books; 1895. | ||

Stone MH. Toward a psychobiological theory of borderline personality disorder: Is irritability the red thread that runs through borderline conditions? Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders. 1988;1(2):2–15. | ||

Crawford HJ. Brain dynamics and hypnosis: attentional and disattentional processes. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1994;42:204–232. | ||

Hilgard ER. Divided Consciousness: Multiple Control in Human Thought and Action. New York, NY: Wiley; 1986. | ||

Rainville P, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH, Price DD. Hypnosis modulates activity in brain structures involved in the regulation of consciousness. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14(6):887–901. | ||

Vermetten E, Douglas Bremner J. Functional brain imaging and the induction of traumatic recall: a cross-correlational review between neuroimaging and hypnosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2004;52(3):280–312. | ||

Egner T, Jamieson G, Gruzelier J. Hypnosis decouples cognitive control from conflict monitoring processes of the frontal lobe. Neuroimage. 2005;27(4):969–978. | ||

Raz A, Fan J, Posner MI. Hypnotic suggestion reduces conflict in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(28):9978–9983. | ||

Bob P, Mashour GA. Schizophrenia, dissociation, and consciousness. Conscious Cogn. 2011;20(4):1042–1049. | ||

Korzekwa MI, Dell PF, Links PS, Thabane L, Fougere P. Dissociation in borderline personality disorder: a detailed look. J Trauma Dissociation. 2009;10(3):346–367. | ||

Pec O, Bob P, Lysaker PH. Trauma, Dissociation and Synthetic Metacognition in Schizophrenia. Act Nerv Super. 2015;57(2):59–70. | ||

Zanarini MC, Jager-Hyman S. Dissociation in borderline personality disorder. In: Dell PF, O’Neil JA, editors. Dissociation and the Dissociative Disorders. DSM-V and Beyond. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009:487–493. | ||

Hunter AM, Korb AS, Cook IA, Leuchter AF. Rostral anterior cingulate activity in major depressive disorder: state or trait marker of responsiveness to medication? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):126–133. | ||

Kopelman A, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P. Morphology of the anterior cingulate gyrus in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to typical neuroleptic exposure. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1872–1878. | ||

Korb AS, Hunter AM, Cook IA, Leuchter AF. Rostral anterior cingulate cortex theta current density and response to antidepressants and placebo in major depression. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120(7):1313–1319. | ||

Mulert C, Juckel G, Brunnmeier M, et al. Rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity in the theta band predicts response to antidepressive medication. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2007;38(2):78–81. | ||

Wang Q, Cheung C, Deng W, et al. White-matter microstructure in previously drug-naive patients with schizophrenia after 6 weeks of treatment. Psychol Med. 2013;43(11):2301–2309. | ||

Yücel M, Brewer WJ, Harrison BJ, et al. Anterior cingulate activation in antipsychotic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(2):155–158. | ||

Kim C, Chung C, Kim J. Task-dependent response conflict monitoring and cognitive control in anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices. Brain Res. 2013;1537:216–223. | ||

Newman LA, Creer DJ, McGaughy JA. Cognitive control and the anterior cingulate cortex: how conflicting stimuli affect attentional control in the rat. J Physiol Paris. 2015;109(1–3):95–103. | ||

Yan H, Tian L, Yan J, et al. Functional and anatomical connectivity abnormalities in cognitive division of anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45659. | ||

Raven JC. Guide to the Standard Progressive Matrices. London: HK Lewis; 1960. | ||

First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. | ||

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33; quiz 34–57. | ||

Atkins M, Burgess A, Bottomley C, Riccio M. Chlorpromazine equivalents: a consensus of opinion for both clinical and research applications. Psychiatr Bull. 1997;21(04):224–226. | ||

Hayasaka Y, Purgato M, Magni LR, et al. Dose equivalents of antidepressants: Evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2015;180:179–184. | ||

Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663–667. | ||

Bernstein EM, Putnam FW. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(12):727–735. | ||

Waller N, Putnam FW, Carlson EB. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(3):300–321. | ||

Bob P. Dissociation processes and their measurement. Ceska Slov Psychiatr. 2000;96(6):301–309. | ||

Ptacek R, Bob P, Paclt I. Dissociative experiences scale – Czech version [kála disociativních zkušeností – Česká verze] Cesk Psychol. 2006;50(3):262–272. | ||

Wing JK, Curtis RH, Beevor AS. HoNOS: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales: Report on Research and Development July 1993–December 1995. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 1996. | ||

Pec O, Cechova D, Pecova J, et al. HoNOS (Health of the Nations Outcome Scales) – An adaptation of the tool for the assessment of symptoms and social functions in serious mentally ill in the Czech conditions and its use. Ceska Slov Psychiatr. 2009;105(6–8):245–249. | ||

Barnow S, Arens EA, Sieswerda S, Dinu-Biringer R, Spitzer C, Lang S. Borderline personality disorder and psychosis: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):186–195. | ||

Weber K, Miller GA, Schupp HT, et al. Early life stress and psychiatric disorder modulate cortical responses to affective stimuli. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(6):1234–1243. | ||

Korb AS, Hunter AM, Cook IA, Leuchter AF. Rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity and early symptom improvement during treatment for major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;192(3):188–194. | ||

Botvinick MM, Cohen JD, Carter CS. Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8(12):539–546. | ||

Kerns JG, Cohen JD. MacDonald AW 3rd, Cho RY, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science. 2004;303(5660):1023–1026. | ||

Kerns JG, Cohen JD, MacDonald AW 3rd, et al. Decreased conflict- and error-related activity in the anterior cingulate cortex in subjects with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1833–1839. | ||

Friedel RO. Early sea changes in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(1):1–4. | ||

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Borderline Personality Disorder. The NICE Guideline on Treatment and Management. Leicester and London: The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009. | ||

National Health and Medical Research Council. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Borderline Personality Disorder. Melbourne: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2012. | ||

Paton C, Crawford MJ, Bhatti SF, Patel MX, Barnes TR. The use of psychotropic medication in patients with emotionally unstable personality disorder under the care of UK mental health services. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(4):e512–e518. | ||

Paris J, Black DW. Borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder: what is the difference and why does it matter? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(1):3–7. | ||

Ruggero CJ, Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D. Borderline personality disorder and the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(6):405–408. | ||

Simpson EB, Yen S, Costello E, et al. Combined dialectical behavior therapy and fluoxetine in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):379–385. | ||

Herpertz SC, Zanarini M, Schulz CS, Siever L, Lieb K. Möller HJ; WFSBP Task Force on Personality Disorders; World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP). World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of personality disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007;8:212–244. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.