Back to Journals » Journal of Blood Medicine » Volume 13

DIC in Pregnancy – Pathophysiology, Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Scores, and Treatments

Authors Erez O , Othman M, Rabinovich A, Leron E , Gotsch F, Thachil J

Received 18 April 2021

Accepted for publication 15 September 2021

Published 6 January 2022 Volume 2022:13 Pages 21—44

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JBM.S273047

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Martin H Bluth

Offer Erez,1,2 Maha Othman,3 Anat Rabinovich,4 Elad Leron,5 Francesca Gotsch,6 Jecko Thachil7

1Maternity Department “D”, Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Soroka University Medical Center, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA; 3Department of Biomedical and Molecular Sciences, School of Medicine, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada; 4Thrombosis and Hemostasis Unit, Hematology Institute, Soroka University Medical Center and Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel; 5Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Soroka University Medical Center, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel; 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata, AOUI Verona, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; 7Department of Haematology, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester, UK

Correspondence: Offer Erez

Maternity Department “D” and Obstetrical Day Care Center, Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Soroka University Medical Center and Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, 84101, Israel

Email [email protected]

Abstract: Obstetrical hemorrhage and especially DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation) is a leading cause for maternal mortality across the globe, often secondary to underlying maternal and/or fetal complications including placental abruption, amniotic fluid embolism, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets), retained stillbirth and acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Various obstetrical disorders can present with DIC as a complication; thus, increased awareness is key to diagnosing the condition. DIC patients can present to clinicians who may not be experienced in a variety of aspects of thrombosis and hemostasis. Hence, DIC diagnosis is often only entertained when the patient already developed uncontrollable bleeding or multi-organ failure, all of which represent unsalvageable scenarios. Beyond the clinical presentations, the main issue with DIC diagnosis is in relation to coagulation test abnormalities. It is widely believed that in DIC, patients will have prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), thrombocytopenia, low fibrinogen, and raised D-dimers. Diagnosis of DIC can be elusive during pregnancy and requires vigilance and knowledge of the physiologic changes during pregnancy. It can be facilitated by using a pregnancy specific DIC score including three components: 1) fibrinogen concentrations; 2) the PT difference – relating to the difference in PT result between the patient’s plasma and the laboratory control; and 3) platelet count. At a cutoff of ≥ 26 points, the pregnancy specific DIC score has 88% sensitivity, 96% specificity, a positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 22, and a negative LR of 0.125. Management of DIC during pregnancy requires a prompt attention to the underlying condition leading to this complication, including the delivery of the patient, and correction of the hemostatic problem that can be guided by point of care testing adjusted for pregnancy.

Keywords: DIC, hyperfibrinolysis, thrombin, pregnancy specific DIC score, maternal mortality, placental abruption

Introduction

The life threatening thrombo-hemorrhagic condition known as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), is generally more common in men than women apart from the reproductive years when pregnancy and its complications increase its prevalence.1 DIC during pregnancy constitutes one of the leading causes for maternal mortality worldwide,2,3 and its rate varies from 0.03%4 to 0.35%.5 This complication is often secondary to underlying maternal and/or fetal complications including placental abruption,6–8 postpartum hemorrhage, amniotic fluid embolism, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, preeclampsia and Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets (HELLP) syndrome,9 and retained stillbirth.10 DIC is characterized by a concomitant over-activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems,11 leading to widespread microvascular thrombosis, disruption of blood supply to different organs, ischemia, and multi-organ failure. This extensive activation of the coagulation cascade leads to consumption and depletion of platelets and coagulation proteins, which can provoke concurrent severe bleeding.12 Of note, obstetric DIC more typically presents with bleeding complications, rather than thrombotic complications. The current review discusses the clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, diagnostic scores, and treatments of DIC in pregnancy.

DIC – Definitions and Types

The Scientific and Standardization Committee (SSC) on DIC of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) defined DIC as

an acquired syndrome characterized by the intravascular activation of coagulation with a loss of localization arising from different causes. It can originate from and cause damage to the microvasculature, which if sufficiently severe, can produce organ dysfunction.13

This definition highlights three important aspects: 1) it is always secondary to other causes, one of them being an obstetric related, such as abruption placentae, pre-eclampsia, or intrauterine fetal death.14 2) DIC represents systemic pathological activation of coagulation. Normal haemostasis refers to the formation of a thrombus in response to endothelial damage and, in these cases, the clotting and fibrinolytic processes are limited to the site of endothelial injury.15 However, in DIC, there is uncontrolled dissemination of this localised thrombotic process which is clearly pathological. In obstetrical DIC, there is extraplacental dissemination of the activated coagulation system which is usually localised to the placenta.16 3) The third crucial aspect of the DIC definition is the role of microvasculature. DIC is a process which originates in the microvasculature, or the vascular endothelium, the most ubiquitous organ in the human body. Excessive and dysregulated thrombin generation due to (and causing) marked endothelial dysfunction can result in organ damage from microthrombi.17 If microvascular dysfunction led to organ damage, it would be considered DIC according to the ISTH definition. If in obstetrical disorders, microthrombi can lead to kidney impairment or cerebrovascular ischaemia, this would be considered as a manifestation of DIC. Microthrombi in the placental vessels can be one of the pathophysiological processes which lead to the complications associated with pre-eclampsia including foetal growth retardation and organ impairment. The microthrombi can arise from localised coagulation activation with platelet aggregation being a significant contributory factor. Most inflammatory disorders like pre-eclampsia are associated with the release of large amounts of Von Willebrand factor into the circulation. In normal circumstances, the ultra large multimer forms of the Von Willebrand factor is cleaved by a metalloprotease enzyme, ADAMTS-13. But in severe inflammation, the enzyme is quenched by the inordinate amount of ultra-large multimers released and the consequence is binding to platelets causing platelet aggregation and microthrombi. In support of this mechanism,18,19 Miodownik et al20 have shown that congenital thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura can present with clinical complications during pregnancy and maternal vascular lesions of under-perfusion in the placenta.

The clinical presentation of DIC can be either thrombosis and/or bleeding as it is a thrombohemorrhagic disorder.21 This may be explained by the extremely rapid pace of thrombin generation in the thrombotic phenotype, while it is relatively slower in the haemorrhagic presentation of this complication (Figure 1). The “hyperfibrinolytic” form of DIC as often observed in postpartum DIC, and abruption22 results from an extremely rapid burst of thrombin generation, whereas a “procoagulant” form of DIC (eg, pre-eclampsia related DIC) may result from an excessive but slower and more gradual form of thrombin generation.23 Although both procoagulant and hyper-fibrinolytic processes may proceed simultaneously in DIC, the clinical presentation of thrombosis or bleeding is determined by the predominant mechanism at a particular time.24

|

Figure 1 The different types of DIC and their clinical presentation. If there is predominance of coagulation pathway activation (denoted as C), in comparison with the fibrinolytic pathways (denoted as F), procoagulant DIC is the result. While the reverse leads to hyperfibrinolytic DIC. Notes: Reprinted from: Thachil J. The Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: does a Diagnosis of DIC Exist Anymore? Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45:100–107.24 With permission. Copyright © Georg Thieme Verlag KG. |

Various obstetrical disorders can present with DIC as a complication; thus, increased awareness is key to diagnosing the condition. DIC patients can present to clinicians who may not be experienced in a variety of aspects of thrombosis and haemostasis. Hence, DIC diagnosis is often only entertained when the patient already developed uncontrollable bleeding or multi-organ failure, all of which represent unsalvageable scenarios.25 Beyond the clinical presentations, the main issue with DIC diagnosis is in relation to coagulation test abnormalities. It is widely believed that in DIC, patients will have thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), low fibrinogen and raised D-dimers.26 These lab markers were considered as diagnostic of DIC in an era when the DIC diagnosis was predominantly made post-mortem or in extremely ill patients.9 The introduction of DIC scoring discussed below generates cut off values of laboratory tests that enable the clinicians to diagnose DIC at early stages of the disease with a more subtle abnormalities of the laboratory tests.

Epidemiology of DIC in Pregnancy

DIC has a higher lifetime prevalence in men than in women, the only period where the incidence of this disorders is similar between the genders is during women’s reproductive years.1 The prevalence of obstetrical DIC differs worldwide ranging from as low as 0.03% in North America to 0.35% in developing countries.2–5,27–29 Differences in quality and accessibility to advance maternity care, as well as inconsistent definitions and diagnostic criteria led to variations in the reported incidence of DIC. Indeed, a cohort from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from USA,30 reported that the prevalence of DIC during pregnancy from 1998 to 2009, increased by 35% from 0.092% to 0.125%30 and linked with nearly a quarter of maternal deaths. Furthermore, DIC was the second most common severe maternal morbidity indicator in the USA between 2010 to 2011, affecting 32 per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations.31

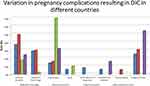

DIC is always secondary to an underlying disorder. Indeed, it is associated with pregnancy complications such as placental abruption, HELLP syndrome, preeclampsia, retained stillbirth, sepsis, post-partum hemorrhage (PPH), acute fatty liver, and amniotic fluid embolism (Figure 2). The proportions of the contribution of each risk factor varies among countries. Indeed, the most frequent pregnancy complication associated with DIC according to Rattray et al4 was placental abruption followed by PPH and preeclampsia. Similarly, Erez et al5 reported that placental abruption was the leading underlying obstetrical disorder leading to DIC especially when it was accompanied by fetal death. Other groups reported preeclampsia32 and fetal death29 to be the leading obstetrical complications associated with DIC (Figure 3). This suggests that early recognition and treatment of complications such preeclampsia or stillbirth may prevent the deterioration to DIC in these patients. Moreover, in countries with early recognition and treatment of preeclampsia and stillbirth, placental abruption (usually unexpected and nonpreventable), becomes the leading obstetrical complication associated with DIC.

|

Figure 2 Obstetrical complications associated with DIC in pregnancy. |

|

Figure 3 Global distribution of obstetrical complications associated with DIC in pregnancy. Note: Data was modified from references 4, 5, 26 and 32. |

Placental abruption seems to be the underlying mechanism for the development of DIC when it is associated with other obstetrical complications including fetal death and HELLP syndrome.7,33–39

Thus, pregnancy is a time point in women’s life in which she is at increased risk to develop DIC as a result from different complications of pregnancy, and especially placental abruption. Prompt attention and treatment of underlying obstetrical disorders and rapid diagnosis and management of placental abruption can reduce the risk for DIC substantially.

Pathophysiology of DIC in Pregnancy

DIC has a complex pathophysiology, the understanding of the normal haemostasis and the highly orchestrated balance involving the various pathways including pro-coagulant/anticoagulant, fibrinolytic/antifibrinolytic and platelet/von Willebrand factor axis during pregnancy, is essential for the characterisation of the haemostatic abnormalities observed during DIC.17

Excessive and uncontrolled in vivo thrombin generation is a key to the development of DIC.21 The excess thrombin generated will activate these pathways in differential manners. Hence, if the procoagulant and antifibrinolytic pathways are both activated “in excess”, then the result would be thrombosis, especially if the natural anticoagulants have also been consumed.25 If the excess thrombin generated drives the fibrinolytic pathway “in excess” of the other pathways, bleeding will commence.9

How does this translate to obstetrical cases? In the placental circulation, maintenance of the blood flow is paramount to ensure adequate oxygenation and nutrition of the foetus.16 At the same time there is local physiological activation of coagulation in the placental bed, in preparation to quench large amounts of bleeding anticipated during parturition.16 Despite the heightened coagulation, clots are not formed in the placental bed except in cases of abnormal placental pathologies.40 In obstetrical disorders, the much-enhanced coagulation process could lead to microvascular clots which impair the appropriate development of the fetus.40 In addition, if the activated procoagulant pathway does not come to a halt, this would spill into the maternal circulation causing systemic coagulopathy, otherwise termed as DIC.24 While, if there is a brisk fibrinolytic response, then this could lead to haemorrhage wherein formation of firm and dense clots is prevented by fibrinolytic proteins.41 Furthermore, D-dimers and fibrin-degradation products that results from fibrinolysis interfere with platelet activation and can impair myometrial contractility.42

Pathological Mechanisms of DIC in Pregnancy

Endothelial Dysfunction and Platelet Activation

Normal pregnancy is associated with activation of maternal leukocytes43 into a state akin to sepsis.44 Nevertheless, placental trophoblast maintain a balanced systemic maternal inflammation during gestation45 by inactivation of maternal leukocytes. However, infectious agents, septic abortion, and amniotic fluid embolism46 leading to sepsis perturbed this balance and can lead to the development of maternal DIC (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 Schematic representation of pathogenic pathways in DIC. Notes: Adapted from: Levi M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. https://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/pages/default.aspx. 2007;35(9):2191–2195.49 With permission. © 2007 by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. |

During sepsis the coagulation system can be activated by Endothelial cells or leucocytes (either intact, dysfunctional, or activated), platelets, and remnants of cell surfaces, inflammatory mediators and coagulation proteins participate in the processes leading to uncontrolled activation of coagulation cascade and DIC47 (Figure 5). These cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), along with propagation of tissue factor (TF) expression on the surface of endothelial cell and leukocytes22,48–54 that can initiate an uncontrolled activation of the coagulation cascade via the TF/factor VIIa pathway leading to thrombin generation if this coagulation response is uncontrolled it will eventually lead to DIC.55 The most significant source of TF is not completely clear as this activator of the coagulation cascade is expressed not only in mononuclear cells in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines (mainly IL-6), but also by vascular endothelial (Figure 5), cancer cells,53,54,56 decidua and placenta.

|

Figure 5 Mechanisms of DIC in sepsis involving endothelial dysfunction and platelet activation. Notes: Reproduced from: Hunt BJ. Bleeding and Coagulopathies in Critical Care. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:847–859.199 Copyright © 2014 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society. |

Despite the potency of TF as a trigger of coagulation, potent anticoagulation pathways can control and limit its activity. However, all the natural anticoagulant pathways (ie, anti-thrombin III, protein C system, and TF pathway inhibitor [TFPI]) are compromised during sepsis mediated DIC.57 Indeed, during DIC antithrombin III concentration are markedly reduced, due to its consumption,58 degradation (by elastase from activated neutrophils),59 and impaired synthesis.49 Moreover, protein C system inhibition due to decreased protein synthesis, cytokine-mediated down-regulation of endothelial thrombomodulin and a drop in the concentration of the free fraction of protein S (protein C co-factor) may further compromise an adequate regulation of thrombin generation.60 Lastly, reduce TFPI function cannot address the increased activation of the extrinsic coagulation cascade.61

Fibrin formation in increased during DIC at the time of maximal activation of coagulation due to the following: 1) there is a continuous elevation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) that suppresses fibrinolysis;49,62 2) platelets activation63 increases TF expression on monocytes especially in the presence of granulocytes in a P-selectin dependent reaction.56 This effect can be attributed to the induction of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) activation following the binding of activated platelets to neutrophils and mononuclear cells.64 Similar mechanisms are activated during DIC in pregnancy resulting from sepsis or systemic maternal inflammation.

Systemic inflammatory response resulting from maternal infection is not unique only for bacterial infection. Indeed, maternal DIC associated with COVID-19 infection was previously reported.65 Unlike the procoagulant DIC in the non-pregnant state,66 during pregnancy, COVID-19 coagulopathy in the third trimester was associated with a clinical manifestation mimicking normotensive HELLP syndrome associated with thrombocytopenia and elevated liver enzymes65 and the coagulopathy was of the hyper fibrinolytic type with fibrinogen concentrations and bleeding.67 This issue is further discussed in a Communication regarding COVID-19 coagulopathy in pregnancy from the ISTH SSC for Women’s Health.

Trophoblast Deportation and Systemic Activation of Maternal Coagulation Cascade

During normal gestation, the trophoblasts face two contradicting hemostatic functions: 1) sustaining of laminar flow of maternal blood in the intervillous space without clotting; and 2) to prevent bleeding at the maternal fetal interface.9 This led to the acquirement of endothelial cell like properties to the syncytiotrophoblast along with the expression of TF to maintain hemostatic function. Placental TF has higher activity in comparison to that expressed on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. The syncytiotrophoblast has also anti coagulation properties as it is able to synthesize Protein C, Protein S and Protein Z as well as pregnancy specific inhibitor of the tissue factor pathway known as TFPI-2 (Placental Protein 5)68–70 to prevent uncontrolled activation of the coagulation cascade.71–74 The prevention of fibrinolysis by the placenta is achieved by placental production of PAI-2 during normal pregnancy.75 These physiological changes during pregnancy are associated with relatively constant tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) concentrations, leading to a prothrombotic state related in part to reduced clot lysis.76

Disruption of trophoblast/decidua integrity would lead to a discharge of potent TF into maternal circulation, and activation of coagulation cascade that in large quantities can lead to uncontrolled systemic thrombin generation and DIC22,77(Figure 6).

Abruption of the placental is the classica example for this mechanism, especially in cases of concealed abruption or when it is complicated by stillbirth. Even though some regard that consumption coagulopathy as the underlying mechanism of placental abruption associated DIC, it seems that there is more to it. Indeed, women with a retro placental clot have a faster developing and more severe form of DIC than those with PPH although they have overall lower blood loss. Indeed, patients who develop placental abruption suffer from a combined coagulopathy incorporating consumption coagulopathy and substantial release of thromboplastin (tissue factor) into the maternal circulation.9,49 In addition, local hypoxia and hypovolemia trigger endothelial response leading to increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, which causes an increased endothelial expression of TF.78 This view is supported by the following: 1) Erez at al22 reported that among women with stillbirth, those with abruption, have higher amniotic fluid TAT complexes concentrations and 2) mice who were injected with placental extracts developed DIC and died. The authors also demonstrated that administration of heparin prevented the death of the injected mice.79 Further study suggested that thromboplastin triggers this response in mice via its effect on clotting time and chemical properties.79 Recent advances in the understanding of the mechanisms of DIC in HELLP syndrome suggest that abruption rather than liver dysfunction is the driving force for the development of DIC in these patients.39 Indeed, the rate of placental abruption was 5.6% in women with HELLP syndrome without DIC in comparison to 42.9% among those with DIC,39 suggesting that the main underlying mechanism leading to DIC in HELLP syndrome is related to trophoblast deportation into maternal circulation rather than to an intrinsic liver dysfunction.

Amniotic fluid embolism, although rare, is a major cause for maternal DIC, though a combined mechanism of activation of coagulation by the TF rich amniotic fluid debris that enter the maternal circulation and the acute systemic maternal inflammatory response further propagating the activation of the coagulation cascade. These patients have a fibrinolytic type of DIC80 observed as unlike placental abruption autopsies of women who died due to amniotic fluid embolism lack evidence of fibrin deposition.81 Moreover, Beller et al82 studied the clotting and fibrinolytic systems of their patient in three blood samples: the first was drawn on admission, the second at the onset of shock and the third at the start of cardiac massage following cardiac arrest. Clotting parameters on admission were normal. The blood in the third sample did not clot even after adding thrombin in excess. Moreover, the clotting time remained prolonged after fibrinogen was added in the presence of excess thrombin indicating that anti-thrombin activity was present. However, protamine sulfate did not restore the clotting time to normal, indicating that the antithrombin activity was not attributable to heparin. The contribution of systemic maternal inflammation to the development of DIC in women with amniotic fluid embolism is highlighted in the report of three cases of amniotic fluid embolism in which the patients had elevated maternal circulation TNFα upon admission prior to the clinical presentation of this complication.46

Obstetrical Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage, especially post-partum is regarded by many4,9,50,83–87 as one of the major causes for DIC in pregnancy. Classically related to PPH, this type of consumption coagulopathy is a complication of uterine atony or rupture, retained placenta or membranes, placenta accreta, or severe lacerations of the birth canal (cervical or vaginal).5,88,89 The characteristics of the DIC developing in these cases are the rapid maternal loss of a large blood volume along with its coagulation factors, resulting in patients who are hemodynamically compromised. Currently, there is a debate whether this form of consumption coagulopathy is truly DIC or just a massive blood loss that depletes the patient’s coagulation factors and can lead to death due to exsanguination.90 However, maternal coagulopathy associated with PPH is not just the loss of blood volume and coagulation factor but rather a more complex complication that can be considered as DIC. This can be attributed to the procoagulant state and increased thrombin generation associated with parturition attributed to the release of TF to the maternal circulation following the separation of the membranes and the placenta;91 along with the systemic inflammation accompanies the process of labor and delivery.92,93 Indeed, women who had PPH are considered at high risk for development of deep vein thrombosis during the puerperium.94 The evidence brought herein, that parturient with PPH have a higher activation of coagulation cascade, beyond physiologic levels for normal pregnancy, suggest that the clinicians who treat these patients must consider them as high risk groups for DIC, even though the fundamental pathology is considered to be the rapid and massive loss of blood and coagulation factors.77 Therefore, PPH requires a careful and prompt assessment and to be treated pharmacologically and/or surgically, and by blood products as well as volume expanders to sustain the maternal circulation in an attempt to prevent the subsequent development of DIC.

Disruption of Liver Function

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is severe, but a rare unique complication of pregnancy mostly observed in nulliparous patients toward the end of the third trimester.95–97 Clinicopathological features of this complication include progressive loss of liver function,98 abnormal renal function99 and DIC.100 The liver presents accumulation of fatty microvascular infiltration of hepatocytes with, without alteration of the overall structure of the liver.98 Nevertheless, the synthetic function of the liver is hampered leading to lower production of fibrinogen and coagulation factors and along with the hemorrhage observed in this syndrome lead to DIC. Indeed, in one of the largest series of acute fatty liver published thus far including 51 patients,101 and 80% of these women according the ISTH DIC score102,103 had DIC similar to the report of Vigil-De Gracia et al100 in which DIC was present in >70% of the patients. The characteristics of the hemostatic parameters of women with DIC in the study of Nelson et al101 demonstrated that patients with DIC had persistent decreased plasma fibrinogen for several days following delivery and mild to moderately elevated fibrin degradation products.101 Unlike women with abruption that their hemostatic parameters recover within hours after delivery those with acute fatty liver requires several days for this to happen as a function of the recovery of the synthetic function of their liver. Thus, DIC is a central component of acute fatty liver and in a way reflects the severity of the hepatic injury.

Collectively, the alteration in maternal physiology associated with pregnancy is further augmented by different pregnancy complications leading to perturbation of the hemostatic system and the development of DIC. It is important to understand the underlying mechanisms associated with the development of DIC in each complication as it will assist the clinician in the prevention and management of DIC in these cases.

Diagnosis of DIC in Pregnancy: Clinical Definitions, Laboratory Findings and Scoring Systems

The determination whether obstetrics coagulopathy results from consumption of coagulation factors, their loss due to uncontrolled bleeding, or both. Isolated intravascular consumption of coagulation factor is a true DIC, whereas their loss due to perfused obstetrical hemorrhage can be regarded as dilutional/consumption coagulopathy. However, it is very hard to make such distinction.25

The hallmark of successful management of this dire complication depends on prompt and accurate recognition of DIC. Unfortunately, often the diagnosis of DIC by the attending physicians is based mainly on clinical presentation of the patient and often made relatively late in the course of the disease. During pregnancy, there is a physiologic change in the maternal plasma concentrations of many of the coagulation parameters leading to a false perception that the status of the coagulation system is normal in cases when the patient is already developing coagulopathy. Moreover, often there is underestimation of the amount of bleeding and the relevant laboratory test are performed too late when the patient is already compromised. It is important to emphasize that there is no single laboratory or clinical test that is sensitive and specific enough to diagnose DIC and the risk to develop DIC is not evident in all cases.4,9,40,46,50,90,104 DIC is a dynamic situation that requires a continuous assessment of the clinical and laboratory parameters including decreasing concentration of fibrinogen and platelet count, prolongation of prothrombin time, and increased concentration of fibrin split products or d-dimers14,105,106 until it resolves. For those reasons, there is a need to: 1) develop means for early diagnosis of DIC by clinicians; and 2) establish a universal definition of DIC in pregnancy. The development of DIC scores was an effort to address both challenges. Such scores need to be simple, easy to perform, and readily available to clinicians worldwide. Indeed, these scores use simple and readily available coagulation tests including platelet count, prothrombin time (PT) prolongation, fibrinogen, and fibrin split products/D-dimer concentrations.

The use of DIC scoring systems was introduced to facilitate the diagnosis of DIC. The ISTH DIC score was proposed in 2001102 followed by that of the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) in 2005,107 both scores have good prediction performance for the diagnosis of DIC and the identification of critically ill non-pregnant patients and their prognosis in intensive care units.103,108–110 None of these scores is adjusted for the physiologic hemostatic changes occurring in pregnancy, limiting their applicability during gestation.

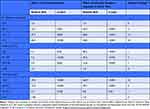

Pregnancy is associated with adaptive changes in the coagulation system that are aimed to address the challenges posed by the need to have extra circulatory maternal blood flow through the placental bed. Thus, the mother has to protect herself from a life-threatening bleeding especially during labor and delivery on one hand, and secure a continuous blood flow through the placental bed to nourish the developing fetus on the other hand.91,111–114 The adaptive changes in the hemostatic system are observed in the maternal circulation, placental bed and amniotic fluid as summarized in Table 1. Women with a normal pregnancy have: 1) excessive thrombin generation;114,115 2) increased agonist derived platelets aggregation;116,117 3) two to three fold increase in fibrinogen concentrations; and 4) towards term they experience a 20% to 1000% increase in factors VII, VIII, IX, X, and XII,118 as well as up to 400% increase in von Willebrand factor.118 By contrast, factors XIII and XI concentrations decrease during gestation and those of factors II & V unchanged.119 The excessive thrombin generation observed during normal pregnancy,114,115 is supported by the observations of elevation in circulating maternal fibrinopeptide A, prothrombin fragments (PF) 1 and 2, and thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) III complexes during pregnancy,91,120–122 especially at the time of and after normal labor123,124 and delivery,121,124 subsequently, in the course of the puerperium their concentrations decrease.124 Pregnancy is also associated with changes in the anticoagulation proteins concentrations. Indeed, there is a 55% decline in free protein S plasma concentration reaching a nadir at birth leading to an increase in resistance to activated protein C118,125. This process is exacerbated by cesarean delivery and infection.118,126 The concentrations of PAI-1 increase by 3 to 4-fold during pregnancy while plasma PAI-2 values, which are negligible before pregnancy reach concentrations of 160 mg/L at delivery.118 Thus, pregnancy is associated with increased clotting potential, as well as decreased anticoagulant properties, and fibrinolysis.92 In addition to the changes in maternal circulation, pregnancy is associated with changes in the local hemostatic mechanisms. Indeed, there is an increase in decidual and myometrial tissue factor.93,127–129 Similarly, changes are observed in the chorioamniotic membranes (mainly the amnion) and in the amniotic fluid.91,130–133

|

Table 1 Adaptive Changes of the Coagulation System During Pregnancy |

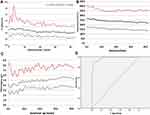

To address the changes of pregnancy in the definition of DIC, Erez et al,5 developed a pregnancy specific DIC score by using platelet count, fibrinogen concentrations and the PT difference – relating to the difference between the patient’s PT and the laboratory control. This diagnostic performance of this score for DIC at a cutoff of ≥26 points were: 88% sensitivity, 96% specificity, a positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 22, and a negative LR of 0.125 (Table 2). To validate the score vs the ISTH DIC score, Erez et al5 compared the diagnostic parameters of both scores in women with placental abruption (n= 684); of them, 21.93% (150/684) needed blood products transfusion and 6.29% (43/684) developed DIC. The pregnancy modified DIC score had 88% sensitivity, 96% specificity, while the modified ISTH score had at a cutoff point of 0.5 had 74% sensitivity, and 95% specificity of for the diagnosis of DIC. An independent validations of these results was reported in a population of French women with obstetrical hemorrhage who were admitted to intensive care unit.134 Among women with liver rupture or hematoma, pregnancy specific DIC score >26 was associated with increased blood product transfusions requirement, longer hospitalizations, and lower neonatal 1 and 5 minutes Apgar scores.135 Moreover, a retrospective analysis of blood product transfusion requirements in patients with PPH revealed that according to the pregnancy specific DIC score, blood transfusion was unnecessary in 179 of the 279 postpartum women (64.1%) suggesting that its use may prevent unnecessary transfusions and their related risks and complications.136 Recently, Clark et al,137 suggested an additional modified version of the ISTH DIC score. Erez et al138 tested the performance of this suggested scoring system on their cohort and found that this score had 14.9% sensitivity, 99.9% specificity, and a LR+ score of 14.9. Despite the good likelihood ratio score, the DIC score presented by Clark et al137 could identify only 13 out of 87 cases of DIC in this cohort, casting a heavy shadow on the clinical utility of this score. Thus, following the study by Erez et al5 coagulation parameters standards of non-pregnant patients can no longer use for the diagnosis of DIC in pregnant women, as “Normal” values of coagulation tests are different during pregnancy, parturition, and puerperium than in the non-pregnant state (Figure 7).

|

Table 2 An Effect of Components of the New DIC Score – Results of Logistic Regression |

|

Figure 7 The changes in the major components of the pregnancy modified DIC score: (A) PT difference: (stands for the difference between the patients PT results and the laboratory control); (B) platelets; (C) fibrinogen, with advancing gestations in women with advancing gestation. (D) ROC curve analysis for the association of the pregnancy specific DIC score with the development of DIC. Notes: Adapted from: Erez O, Novak L, Beer-Weisel et al. DIC score in pregnant women–a population based modification of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis score. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93240.5 Copyright: © 2014 Erez et al. Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). |

Other DIC scores in pregnancy were suggested by: 1) Terao et al139 in 1987 developed a DIC score that included three categories, etiology, clinical manifestation, and laboratory tests (PT, fibrinogen, FDP, and platelets). The study included 77 women with DIC recruited from 100 centers in Japan. A DIC score ≥7 was considered positive and identified 90% (70/77) of the patients. Of note, this score was not validated in comparison to the normal obstetric population, and it is currently not in clinical use outside of Japan. 2) the utilization of the fibrinogen/C-reactive protein (CRP) ratio as a tool to diagnose the development of DIC among women with HELLP syndrome by Windsperger et al140 demonstrated a good sensitivity and perform better than fibrinogen concentrations alone in these patients.

The incorporation of pregnancy specific scoring system to diagnose DIC in pregnant women is an accurate and easy to use and may assist clinicians in real time during at the Labor and Delivery wards. However, there is a need for an international consensus on the diagnostic criteria and scoring for DIC in pregnancy, this will facilitate standardization of the definition and will support international research effort in this dire complication of pregnancy.

Point of Care Testing in the Management of DIC During Pregnancy and Parturition

Standard laboratory tests have limitations, including absence of real-time data and incapacity to determine the functionality of the hemostatic system of whole blood (ie the strength of blood clot, and platelet function). Point of care viscoelastic tests Thromboelastography (TEG); and Rotational Thromboelastometry (ROTEM) are the most widely studied viscoelastic tests which provide a rapid assessment of in vivo coagulation. Specific TEG/ROTEM values were defined for pregnancy16,26,84,141,142 and at the time of delivery.143 Indeed, in comparison to the non-pregnant state, the characteristics of TEG differ significantly between pregnant and non-pregnant women, displaying a shorter R and K a higher α angle and maximum amplitude suggesting that clot formation is faster and bigger during pregnancy especially during the third trimester.144 The ROTEM parameters display similar changes in comparison to the non-pregnant state.145 Moreover, in a study by Rigouzzo at al146 the TEG parameters (the maximum amplitude of K ≤63.5 mm and time to maximum rate of thrombus generation) had excellent diagnostic performance for fibrinogen concentration ≤2g/L and Platelet count ≤80,000/mm3 in women with postpartum hemorrhage. Suggesting that TEG can be an excellent point of care testing to identify women with severe PPH at risk to develop DIC. Encouraging data show these tests may enable early detection of dysfunctional coagulation and hyperfibrinolysis,147 allowing adequate surveillance and prompt intervention.14,148 A study of 21 patients classified according to the ISTH DIC score, proposed a thromboelastographic score had 95.2% sensitivity, 81.0% specificity, and an AUC of 0.957 for identifying overt DIC149 thus allowing, along other diagnostic and prognostic modalities (ie DIC scores), an adequate surveillance and, eventually, a prompt intervention during the early stages of DIC in pregnancy.150

Treatment of DIC in Pregnancy

Prevention, early diagnosis and treatment of obstetrical hemorrhage are the heart of midwifery.

Prevention of obstetrical hemorrhage is based on identification of patients at risk for peripartum bleeding, active management of the third stage of labor and prompt diagnosis and management of obstetrical complications that may be associated with the development of DIC even in the absence of labor, the interested reader is referred to the guidelines of the professional committees and selected reviews (ref).

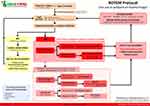

The basic principles for treating obstetrical DIC are presented in Figure 8 and include the following:9,14,106,151 1) treatment and resolution of the underlying condition leading to DIC; 2) fast and prompt delivery or termination of pregnancy (before the threshold of viability). The delivery options should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team and consider the safest mode of delivery to the mother, how fast she is expected to deliver, what are the resources of blood products and other supportive mechanisms available, and can she sustain a surgery; 3) supportive treatment with blood product transfusion, surgical care and related measures; 4) rigorous clinical and laboratory patients surveillance; 5) prompt involvement of needed consultant such as hematologists, gynecological surgeons, anesthesiologists and others; and 6) in small to medium size health care facilities it is important to estimate whether their blood bank can support a massive blood transfusion and, if necessary, contact regional or larger hospitals for assistance or for transferring the patient.

|

Figure 8 Principles of Diagnosis and management of DIC in pregnancy. Notes: Reproduced from: Erez O. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in pregnancy - Clinical phenotypes and diagnostic scores. Thromb Res. 2017;151203 1:S56-S60.200 With permission. Copyright © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. |

Treatment algorithms for obstetric DIC always involve simultaneous blood product transfusion as a replacement of women’s blood loss. Specific transfusion protocols have been previously published and the interested reader is referred to the specific papers on the subject.152 The harmonized guidance from the ISTH151,153 give a fine definition for the thresholds for blood products transfusion, and massive transfusion protocols with fixed RBC: plasma: platelet ratios,83,152 are mostly being used, but this recommendation is under debate.154 The response to blood component therapy should be monitored both clinically and with repeated assessments of the platelet count and coagulation parameters. For further reading, the reader is referred to the published guidelines for blood component replacement from national professional societies155–159 and the scientific subcommittees on Women’s Health Issues in Thrombosis and Hemostasis and on DIC of the ISTH.41,160

Viscoelastic Hemostatic Assays Guided Transfusion Protocols

During DIC there is a rapid consumption of fibrinogen and coagulation factors, making the monitoring and maintenance of proper blood products administration by conventional laboratory tests challenging, as rapid correction of blood component deficiencies is required at a rate faster than their depletion. ROTEM\TEG allow early detection and dynamic monitoring of clotting abnormalities, and transfusion needed; hence, they could potentially be used as guidance for administration of blood components. Favorable evidence regarding use of these tests, especially to guide fibrinogen replacement therapy in management of obstetric complications, is accumulating.123,147,150,161–166 Further research demonstrated that the use of ROTEM- FIBTEM A5 as a point of care testing for fibrinogen concentration assisted in targeting patients with postpartum hemorrhage who will require blood product transfusion. The rational for its use was that while Clauss fibrinogen tests results are available within an hour of venipuncture, those of FIBTEM A5 are available within 10 minutes. The authors use a FIBTEM A5 of <15 that can be translated to fibrinogen concentration of 3 grams/Liter or 300mg/Dl as a cutoff point that requires obstetrician attention in women with PPH and developed an algorithm for the management of women with PPH based on the FIBTEM A5 results (Figure 9).167–169 These encouraging results in the pregnant population await further studies before widespread clinical application of VHA scan as point of care testing to guide blood product transfusion in women with PPH can be implemented.170–173

|

Figure 9 Algorithm for the treatment of obstetrical hemorrhage based on FIBTEM and fibrinogen concentrations. Notes: Reprinted from: Collins PW, Bell SF, de Lloyd L, Collis RE. Management of postpartum haemorrhage: from research into practice, a narrative review of the literature and the Cardiff experience. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2019;37:106–117.167 With permission Crown Copyright © 2018 Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. |

Another possible clinical application of VHAs could be the identification of women who show a severe hypercoagulable state and could benefit from antithrombotic prophylaxis. In a recent case-control study, Spiezia et al evaluated ROTEM profiles in women with preeclampsia in comparison to healthy pregnant women.174 Characteristic hypercoagulable ROTEM profiles in women with preeclampsia were found.

Treatments for Coagulopathy

Based on the pathogenesis of microvascular failure and coagulation activation in DIC, strategies aimed at the inhibition of coagulation activation have been found favorable in experimental and clinical studies. Most RCTs have been carried out in patients with sepsis, and evidence in obstetric DIC is limited. Tranexamic acid is used as an adjunct to blood product administration and has been studied in PPH. Recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) is used as a second line treatment in women in whom massive transfusion does not halt blood loss. All other treatment modalities are considered experimental at this stage.

Antifibrinolytic Agents

Tranexamic acid (TXA) has been suggested as a treatment for coagulopathy in PPH.175 TXA prevents the activation of plasminogen by plasmin by blocking its lysine binding sites.175 Four recent systematic reviews of the use of TXA for reduction of blood loss in PPH came to conflicting results.176–179 TXA appears to be a promising drug for the prevention of PPH after cesarean and vaginal delivery.180,181 Patients with the organ failure or non-symptomatic type of DIC may not benefit from antifibrinolytic agents as fibrinolysis is needed for the resolution of widespread fibrin thromboses resulting by DIC.182 The usual dose is 1gr administered intravenously over 10 minutes up to 4 times daily.183

Recombinant Activated Factor VII (rFVIIa)

Guidelines suggest that administration of rFVIIa is warranted in active obstetrical hemorrhage that does not resolve by conventional treatment or to prevent hysterectomy.160 In such cases, this hemostatic agent decreases maternal mortality due to obstetrical hemorrhage.184,185 A review of 99 cases of its use in DIC, of them 32 due to PPH, reported that a median dose of 67.2 mg/kg is successful in controlling the ongoing obstetrical hemorrhage.186 Optimal use of rFVIIa requires exclusion or correction of metabolic acidosis, hypothermia, hypofibrinogenemia, and thrombocytopenia.187 A recent RCT, reported that rFVIIa reduces by 30% the need for second-line treatments (interventional hemostatic procedures, blood transfusions).188 However, as the use of rFVIIa increases by two fold the risk for arterial thrombosis, adequate thromboprophylaxis should be administrated to these patients following the acute hemorrhagic event. The optimal dose is unclear, however it is preferable to start with a low dose (40–60mcg/kg) to reduce the risk of thrombotic events. Higher doses (eg 90mcg/kg) can be used if the patient is unstable or if blood loss is brisk and ongoing.

Potential Experimental Treatments

Fibrinogen Concentrate

Human fibrinogen concentrates have been used for substitution therapy in cases of hypofibrinogenemia, dysfibrinogenemia, and afibrinogenemia. This product has the potential to administer relative high quantity of fibrinogen in relatively low volume of transfusion in women with obstetrical hemorrhage. Its benefits are that it is readily available, as it can be kept in room temperature or refrigerators, and it can introduce higher quantity of fibrinogen without the need to transfuse large plasma volume as in FFP transfusion.167,189 The obstetric bleeding strategy for Wales (OBSCYMRU) initiative has adopted the use for fibrinogen concentrate at the treatment of choice for women with active obstetrical hemorrhage who has fibrinogen concentrations <2g/L or FIBTEM A5<11mm167 (Figure 10). However, this Fibrinogen concentrate is not readily available worldwide and the current standard of care for the administration of high concentration of fibrinogen in a low volume transfusion is by cryoprecipitate. Each vial contains approximately 1000mg of fibrinogen, doses are repeated according to TEG/ROTEM guidance.

|

Figure 10 The ROTEM protocol of the OBS Cymru (the Obstetric Bleeding Strategy for Wales) initiative. Notes: Reproduced with permission from: ROTEM Protocol (For use in postpartum haemorrhage); 2018. Obstetric Bleeding Strategy for Wales. Available from: https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/improvement-cymru/improvement-cymru-programmes/maternity-cymru/obs-cymru/obstetric-bleeding-strategy-cymru/rotem-point-of-care-testing.201 Copyright © 2016, Public Health Wales. |

Desmopressin- 1-Deamino-8-D-Arginine Vasopressin (DDAVP)

The synthetic Anti diuretic hormone analog increases factor VIII concentrations and VWF release from endothelial cells, promoting platelet aggregation and adhesion. DDAVP can reduce bleeding resulting from obstetrical hemorrhage with a good safety profile.190 The current evidence although limited suggest that DDAVP may be beneficial in DIC resulting from abnormal platelet activity.191 However, it is not part of standard treatment protocols.

Recombinant Human Soluble Thrombomodulin (rhTM)

This agent was reported to potentially lower morbidity and mortality of patients with DIC due to sepsis.192–194 This anti-coagulant reduces excessive thrombin activation and regulates the imbalance of the coagulation system. The administration rhTM to patients with obstetric DIC in a single-center, retrospective cohort study, resulted in improved platelet count, D-dimer and fibrinogen concentrations, and prothrombin time, as well as reduction in the need for platelet transfusions; however, these observations were not associated with a change in the rate of organ failure.195 There is a need for more substantial evidence prior for the inclusion of rhTM in the treatment protocols for obstetrical DIC.

Anticoagulants

In cases of DIC with predominant hypercoagulation and thrombotic phenotype heparin can partly inhibit coagulation in this setting196 and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is superior to unfractionated heparin (UFH) for treating this type of DIC.197 However, the majority of cases of DIC in pregnancy are associated with a hemorrhagic phenotype of DIC, and heparin may increase bleeding, especially if adequate replacement therapy for consumed clotting factors has not been achieved, hence it is not recommended.

Conclusions

DIC in obstetrics is a life-threatening complication that is secondary to obstetrical and non-obstetrical related complications of pregnancy. Solid clinical and epidemiologic data is still lacking. The SSC Subcommittees on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) and Women’s Issues in Thrombosis and Hemostasis of the International Society for Thrombosis and Hemostasis have launched a global registry of DIC in pregnancy to collect this information. We encourage physicians from across the globe to participate using this link https://redcap.isth.org/surveys/?s=KFC8RN8XWC. The diagnosis of DIC can be elusive during pregnancy and requires vigilance and knowledge of the physiologic changes during pregnancy. Pregnancy specific DIC scores and adjustment of the cutoff of point of care testing can facilitate the diagnosis and the management of DIC in pregnancy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Singh B, Hanson AC, Alhurani R, et al. Trends in the incidence and outcomes of disseminated intravascular coagulation in critically ill patients (2004–2010): a population-based study. Chest. 2013;143:1235–1242. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2112

2. Cunningham FG, Nelson DB. Disseminated intravascular coagulation syndromes in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:999–1011. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001110

3. Gulumser C, Engin-Ustun Y, Keskin L, et al. Maternal mortality due to hemorrhage: population-based study in Turkey. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:3998–4004. doi:10.1080/14767058.2018.1481029

4. Rattray DD, O’Connell CM, Baskett TF. Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation in obstetrics: a tertiary centre population review (1980 to 2009). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:341–347. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35214-8

5. Erez O, Novack L, Beer-Weisel R, et al. DIC score in pregnant women–a population based modification of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis score. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93240. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093240

6. Onishi K, Tsuda H, Fuma K, et al. The impact of the abruption severity and the onset-to-delivery time on the maternal and neonatal outcomes of placental abruption. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;33:1–9.

7. Qiu Y, Wu L, Xiao Y, Zhang X. Clinical analysis and classification of placental abruption. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;2:1–5.

8. Kilicci C, Ozkaya E, Karakus R, et al. Early low molecular weight heparin for postpartum hemorrhage in women with pre-eclampsia. Is it effective to prevent consumptive coagulopathy? J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:410–414. doi:10.1080/14767058.2018.1494708

9. Thachil J, Toh CH. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in obstetric disorders and its acute haematological management. Blood Rev. 2009;23:167–176. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2009.04.002

10. Romero R, Copel JA, Hobbins JC. Intrauterine fetal demise and hemostatic failure: the fetal death syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1985;28:24–31. doi:10.1097/00003081-198528010-00004

11. Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T, Ten Cate H. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenetic pathways of disseminated intravascular coagulation result in more insight in the clinical picture and better management strategies. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2001;27:569–575. doi:10.1055/s-2001-18862

12. Franchini M, Lippi G, Manzato F. Recent acquisitions in the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb J. 2006;4:4. doi:10.1186/1477-9560-4-4

13. Taylor FB

14. Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, Watson HG. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:24–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x

15. Gando S, Levi M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16038. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.38

16. Erez O, Mastrolia SA, Thachil J. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in pregnancy: insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:452–463. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.054

17. Thachil J. Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: a Practical Approach. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:230–236. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001123

18. Matevosyan K, Sarode R. Thrombosis, Microangiopathies, and Inflammation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41:556–562. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1556587

19. Bockmeyer CL, Claus RA, Budde U, et al. Inflammation-associated ADAMTS13 deficiency promotes formation of ultra-large von Willebrand factor. Haematologica. 2008;93:137–140. doi:10.3324/haematol.11677

20. Miodownik S, Pikovsky O, Erez O, Kezerle Y, Lavon O, Rabinovich A. Unfolding the pathophysiology of congenital thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in pregnancy: lessons from a cluster of familial cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:

21. Thachil J, Toh CH. Current concepts in the management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Res. 2012;129(Suppl 1):S54–9. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(12)70017-8

22. Erez O, Gotsch F, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. Evidence of maternal platelet activation, excessive thrombin generation, and high amniotic fluid tissue factor immunoreactivity and functional activity in patients with fetal death. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:672–687. doi:10.1080/14767050902853117

23. Wada H, Matsumoto T, Yamashita Y, Hatada T. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: testing and diagnosis. Int J Clin Chem. 2014;436:130–134.

24. Thachil J. The Elusive Diagnosis of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation: does a Diagnosis of DIC Exist Anymore? Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45:100–107. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1677042

25. Thachil J. Disseminated intravascular coagulation - new pathophysiological concepts and impact on management. Expert Rev Hematol. 2016;9:803–814. doi:10.1080/17474086.2016.1203250

26. Levi M, Meijers JC. DIC: which laboratory tests are most useful. Blood Rev. 2011;25:33–37. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2010.09.002

27. Hossain N, Paidas MJ. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Semin Perinatol. 2013;37:257–266. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2013.04.008

28. Kobayashi T. Obstetrical disseminated intravascular coagulation score. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1500–1506. doi:10.1111/jog.12426

29. Kor-anantakul O, Lekhakula A. Overt disseminated intravascular coagulation in obstetric patients. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90:857–864.

30. Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:5–12. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000564

31. Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1029–1036. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826d60c5

32. Naz H, Fawad A, Islam A, Shahid H, Abbasi AU. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2011;23:111–113.

33. Haram K, Mortensen JH, Mastrolia SA, Erez O. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in the HELLP syndrome: how much do we really know? J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:779–788. doi:10.1080/14767058.2016.1189897

34. Latif E, Adam S, Rungruang B, et al. Use of uterine artery embolization to prevent peripartum hemorrhage of placental abruption with fetal demise & severe DIC. J Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2016;9:325–331. doi:10.3233/NPM-16915108

35. Myers J, Wu G, Shapiro RE, Vallejo MC. Preeclampsia Induced Liver Dysfunction Complicated by Disseminated Intravascular Coagulopathy and Placental Abruption: a Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2019;2019:4305849.

36. Ni S, Wang X, Cheng X. The comparison of placental abruption coupled with and without preeclampsia and/or intrauterine growth restriction in singleton pregnancies. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;54:1–6.

37. Onishi K, Tsuda H, Fuma K, et al. The impact of the abruption severity and the onset-to-delivery time on the maternal and neonatal outcomes of placental abruption. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:3775–3783. doi:10.1080/14767058.2019.1585424

38. Takeda J, Takeda S. Management of disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with placental abruption and measures to improve outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62:299–306. doi:10.5468/ogs.2019.62.5.299

39. Gomez-Tolub R, Rabinovich A, Kachko E. et al. Placental abruption as a trigger of DIC in women with HELLP syndrome: a population-based study. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;2:1–11. doi:10.1080/14767058.2020.1818200

40. Montagnana M, Franchi M, Danese E, Gotsch F, Guidi GC. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in obstetric and gynecologic disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:404–418. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1254049

41. Rabinovich A, Abdul-Kadir R, Thachil J, Iba T, Othman M, Erez O. DIC in obstetrics: diagnostic score, highlights in management, and international registry-communication from the DIC and Women’s Health SSCs of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17:1562–1566. doi:10.1111/jth.14523

42. Sher G. Pathogenesis and management of uterine inertia complicating abruptio placentae with consumption coagulopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;129:164–170. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(77)90739-6

43. Naccasha N, Gervasi MT, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Phenotypic and metabolic characteristics of monocytes and granulocytes in normal pregnancy and maternal infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1118–1123. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.117682

44. Sacks GP, Studena K, Sargent K, Redman CW. Normal pregnancy and preeclampsia both produce inflammatory changes in peripheral blood leukocytes akin to those of sepsis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:80–86. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70254-6

45. Zhu A, Romero R, Huang JB, Clark A, Petty HR. Maltooligosaccharides from JEG-3 trophoblast-like cells exhibit immunoregulatory properties. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:54–64. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00851.x

46. Romero R, Kadar N, Vaisbuch E, Hassan SS. Maternal death following cardiopulmonary collapse after delivery: amniotic fluid embolism or septic shock due to intrauterine infection? Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;64:113–125.

47. Anas AA, Wiersinga WJ, de Vos AF, van der Poll T. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of bacterial sepsis. Neth J Med. 2010;68:147–152.

48. Takai H, Kondoh E, Sato Y, Kakui K, Tatsumi K, Konishi I. Disseminated intravascular coagulation as the presenting sign of gastric cancer during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:1717–1719. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01561.x

49. Levi M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2191–2195. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000281468.94108.4B

50. Levi M. Pathogenesis and management of peripartum coagulopathic calamities (disseminated intravascular coagulation and amniotic fluid embolism). Thromb Res. 2013;131(Suppl 1):S32–4. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(13)70017-3

51. Levi M, van der Poll T. Inflammation and coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S26–34. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c98d21

52. Seki Y, Wada H, Kawasugi K, et al. A prospective analysis of disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with infections. Intern Med. 2013;52:1893–1898. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.52.0571

53. Sung JY, Kim JE, Kim KS, Han KS, Kim HK. Differential expression of leukocyte receptors in disseminated intravascular coagulation: prognostic value of low protein C receptor expression. Thromb Res. 2014;134:1130–1134. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2014.08.026

54. Kvolik S, Jukic M, Matijevic M, Marjanovic K, Glavas-Obrovac L. An overview of coagulation disorders in cancer patients. Surg Oncol. 2010;19:e33–46. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2009.03.008

55. Levi M, van der Poll T. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: a review for the internist. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8:23–32. doi:10.1007/s11739-012-0859-9

56. Osterud B. Tissue factor expression by monocytes: regulation and pathophysiological roles. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1998;9(Suppl 1):S9–14.

57. Levi M, de Jonge E, van der Poll T. Rationale for restoration of physiological anticoagulant pathways in patients with sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S90–4. doi:10.1097/00003246-200107001-00028

58. Choi Q, Hong KH, Kim JE, Kim HK. Changes in plasma levels of natural anticoagulants in disseminated intravascular coagulation: high prognostic value of antithrombin and protein C in patients with underlying sepsis or severe infection. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34:85–91. doi:10.3343/alm.2014.34.2.85

59. Himmelreich G, Jochum M, Bechstein WO, et al. Mediators of leukocyte activation play a role in disseminated intravascular coagulation during orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1994;57:354–358.

60. Esmon CT. Role of coagulation inhibitors in inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:51–56. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1616200

61. Levi M. The imbalance between tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1914–1915. doi:10.1097/00003246-200208000-00046

62. Slofstra SH, Spek CA, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Hematol J. 2003;4:295–302. doi:10.1038/sj.thj.6200263

63. Löwenberg EC, Meijers JC, Levi M. Platelet-vessel wall interaction in health and disease. Neth J Med. 2010;68:242–251.

64. Furie B, Furie BC. Role of platelet P-selectin and microparticle PSGL-1 in thrombus formation. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:171–178.

65. Vlachodimitropoulou Koumoutsea E, Vivanti AJ, Shehata N, et al. COVID-19 and acute coagulopathy in pregnancy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1648–1652. doi:10.1111/jth.14856

66. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2020;18:844–847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

67. Kadir RA, Kobayashi T, Iba T, et al. COVID-19 coagulopathy in pregnancy: critical review, preliminary recommendations, and ISTH registry-Communication from the ISTH SSC for Women’s Health. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:3086–3098. doi:10.1111/jth.15072

68. Seppälä M, Wahlström T, Bohn H. Circulating levels and tissue localization of placental protein five (PP5) in pregnancy and trophoblastic disease: absence of PP5 expression in the malignant trophoblast. Int J Cancer. 1979;24:6–10. doi:10.1002/ijc.2910240103

69. Obiekwe BC, Chard T. Placental protein 5: circulating levels in twin pregnancy and some observations on the analysis of biochemical data from multiple pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1981;12:135–141. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(81)90068-X

70. Than G, Bohn H, Szabo D. Advances in Pregnancy- Related Protein Research. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2020.

71. Reverdiau P, Jarousseau AC, Thibault G, et al. Tissue factor activity of syncytiotrophoblast plasma membranes and tumoral trophoblast cells in culture. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:49–54. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1653724

72. Aharon A, Brenner B, Katz T, Miyagi Y, Lanir N. Tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor levels in trophoblast cells: implications for placental hemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:776–786. doi:10.1160/TH04-01-0033

73. Hubé F, Reverdiau P, Iochmann S, Trassard S, Thibault G, Gruel Y. Demonstration of a tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 messenger RNA synthesis by pure villous cytotrophoblast cells isolated from term human placentas. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1888–1894. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.011858

74. Udagawa K, Miyagi Y, Hirahara F, et al. Specific expression of PP5/TFPI2 mRNA by syncytiotrophoblasts in human placenta as revealed by in situ hybridization. Placenta. 1998;19:217–223. doi:10.1016/S0143-4004(98)90011-X

75. van Wersch JW, Ubachs JM. Blood coagulation and fibrinolysis during normal pregnancy. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1991;29:45–50.

76. Robb AO, Mills NL, Din JN, et al. Acute endothelial tissue plasminogen activator release in pregnancy. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:138–142. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03207.x

77. Oyelese Y, Ananth CV. Placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1005–1016. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000239439.04364.9a

78. Krikun G, Huang ST, Schatz F, Salafia C, Stocco C, Lockwood CJ. Thrombin activation of endometrial endothelial cells: a possible role in intrauterine growth restriction. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:245–253. doi:10.1160/TH06-07-0387

79. Schneider CL. The active principle of placental toxin; thromboplastin; its inactivator in blood; antithromboplastin. Am J Physiol. 1947;149:123–129. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.149.1.123

80. Collins NF, Bloor M, McDonnell NJ. Hyperfibrinolysis diagnosed by rotational thromboelastometry in a case of suspected amniotic fluid embolism. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013;22:71–76. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.09.008

81. Schneider CL. Fibrin embolism (disseminated intravascular coagulation) with defibrination as one of the end results during placenta abruptio. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1951;92:27–34.

82. Beller FK, Douglas GW, Debrovner CH, Robinson R. The fibrinolytic system in amniotic fluid embolism. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1963;87:48–55. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)35142-0

83. McLintock C, James AH. Obstetric hemorrhage. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1441–1451. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04398.x

84. Levi M, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:586–592. doi:10.1056/NEJM199908193410807

85. Weiner CP. The obstetric patient and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Clin Perinatol. 1986;13:705–717. doi:10.1016/S0095-5108(18)30794-2

86. Grönvall M, Tikkanen M, Metsätähti M, Loukovaara M, Paavonen J, Stefanovic V. Pelvic arterial embolization in severe obstetric hemorrhage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:716–719. doi:10.1111/aogs.12376

87. Rath WH. Postpartum hemorrhage–update on problems of definitions and diagnosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:421–428. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01107.x

88. Knight M. The findings of the MBRRACE-UK confidential enquiry into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity. Obstet Gynaecol Reproduct Med. 2019;29:21–23. doi:10.1016/j.ogrm.2018.12.003

89. Green L, Knight M, Seeney FM, et al. The epidemiology and outcomes of women with postpartum haemorrhage requiring massive transfusion with eight or more units of red cells: a national cross-sectional study. Bjog. 2016;123:2164–2170. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13831

90. Levi M. Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in pregnancy and the peri-partum period. Thromb Res. 2009;123(Suppl 2):S63–4. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70013-1

91. de Boer K, Ten Cate JW, Sturk A, Borm JJ, Treffers PE. Enhanced thrombin generation in normal and hypertensive pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:95–100. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(89)90096-3

92. Lockwood CJ. Pregnancy-associated changes in the hemostatic system. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:836–843. doi:10.1097/01.grf.0000211952.82206.16

93. Kuczyński J, Uszyński W, Zekanowska E, Soszka T, Uszyński M. Tissue factor (TF) and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) in the placenta and myometrium. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;105:15–19. doi:10.1016/S0301-2115(02)00113-6

94. Beller FK, Ebert C. The coagulation and fibrinolytic enzyme system in pregnancy and in the puerperium. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1982;13:177–197. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(82)90028-4

95. Castro MA, Goodwin TM, Shaw KJ, Ouzounian JG, McGehee WG. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and antithrombin III depression in acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:211–216.

96. Reyes H, Sandoval L, Wainstein A, et al. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a clinical study of 12 episodes in 11 patients. Gut. 1994;35:101–106. doi:10.1136/gut.35.1.101

97. Pockros PJ, Peters RL, Reynolds TB. Idiopathic fatty liver of pregnancy: findings in ten cases. Medicine. 1984;63:1–11. doi:10.1097/00005792-198401000-00001

98. Riely CA, Latham PS, Romero R, Duffy TP. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy. A reassessment based on observations in nine patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:703–706. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-106-5-703

99. Slater DN, Hague WM. Renal morphological changes in idiopathic acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Histopathology. 1984;8:567–581. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1984.tb02369.x

100. Vigil-de Gracia P. Acute fatty liver and HELLP syndrome: two distinct pregnancy disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;73:215–220. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00364-2

101. Nelson DB, Yost NP, Cunningham FG. Hemostatic dysfunction with acute fatty liver of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:40–46. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000296

102. Taylor FB, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M. (ISTH) SSoDICDotISoTaH. Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1327–1330.

103. Bakhtiari K, Meijers JC, de Jonge E, Levi M. Prospective validation of the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2416–2421. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000147769.07699.E3

104. Gasem T, Al Jama FE, Burshaid S, Rahman J, Al Suleiman SA, Rahman MS. Maternal and fetal outcome of pregnancy complicated by HELLP syndrome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:1140–1143. doi:10.3109/14767050903019627

105. Gando S, Wada H, Thachil J; (ISTH) SaSCoDotISoTaH. Differentiating disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with the fibrinolytic phenotype from coagulopathy of trauma and acute coagulopathy of trauma-shock (COT/ACOTS). J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:826–835. doi:10.1111/jth.12190

106. Wada H, Thachil J, Di Nisio M, et al. Harmonized guidance for disseminated intravascular coagulation from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis and the current status of anticoagulant therapy in Japan: a rebuttal. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(11):2078–2079. doi:10.1111/jth.12366

107. Gando S, Iba T, Eguchi Y, et al. A multicenter, prospective validation of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: comparing current criteria. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:625–631. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000202209.42491.38

108. Angstwurm MW, Dempfle CE, Spannagl M. New disseminated intravascular coagulation score: a useful tool to predict mortality in comparison with Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II and Logistic Organ Dysfunction scores. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:

109. Asakura H, Wada H, Okamoto K, et al. Evaluation of haemostatic molecular markers for diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with infections. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:282–287. doi:10.1160/TH05-04-0286

110. Cavkaytar S, Ugurlu EN, Karaer A, Tapisiz OL, Danisman N. Are clinical symptoms more predictive than laboratory parameters for adverse maternal outcome in HELLP syndrome? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:648–651. doi:10.1080/00016340601185384

111. Yuen PM, Yin JA, Lao TT. Fibrinopeptide A levels in maternal and newborn plasma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1989;30:239–244. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(89)90007-5

112. Sørensen JD, Secher NJ, Jespersen J. Perturbed (procoagulant) endothelium and deviations within the fibrinolytic system during the third trimester of normal pregnancy. A possible link to placental function. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:257–261. doi:10.3109/00016349509024445

113. Walker MC, Garner PR, Keely EJ, Rock GA, Reis MD. Changes in activated protein C resistance during normal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:162–169. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70456-3

114. Bellart J, Gilabert R, Miralles RM, Monasterio J, Cabero L. Endothelial cell markers and fibrinopeptide A to D-dimer ratio as a measure of coagulation and fibrinolysis balance in normal pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:17–21. doi:10.1159/000009989

115. Chaiworapongsa T, Espinoza J, Yoshimatsu J, et al. Activation of coagulation system in preterm labor and preterm premature rupture of membranes. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med. 2002;11:368–373. doi:10.1080/jmf.11.6.368.373

116. Yoneyama Y, Suzuki S, Sawa R, Otsubo Y, Power GG, Araki T. Plasma adenosine levels increase in women with normal pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1200–1203. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.104832

117. Sheu JR, Hsiao G, Luk HN, et al. Mechanisms involved in the antiplatelet activity of midazolam in human platelets. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:651–658. doi:10.1097/00000542-200203000-00022

118. Bremme KA. Haemostatic changes in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2003;16:153–168. doi:10.1016/S1521-6926(03)00021-5

119. Eichinger S, Weltermann A, Philipp K, et al. Prospective evaluation of hemostatic system activation and thrombin potential in healthy pregnant women with and without factor V Leiden. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1232–1236. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1614366

120. Reinthaller A, Mursch-Edlmayr G, Tatra G. Thrombin-antithrombin III complex levels in normal pregnancy with hypertensive disorders and after delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:506–510. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02520.x

121. Uszyński M. Generation of thrombin in blood plasma of non-pregnant and pregnant women studied through concentration of thrombin-antithrombin III complexes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;75:127–131. doi:10.1016/S0301-2115(97)00101-2

122. Reber G, Amiral J, de Moerloose P. Modified antithrombin III levels during normal pregnancy and relationship with prothrombin fragment F1 + 2 and thrombin-antithrombin complexes. Thromb Res. 1998;91:45–47. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(98)00043-7

123. Mallaiah S, Barclay P, Harrod I, Chevannes C, Bhalla A. Introduction of an algorithm for ROTEM-guided fibrinogen concentrate administration in major obstetric haemorrhage. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:166–175. doi:10.1111/anae.12859

124. Andersson T, Lorentzen B, Hogdahl H, Clausen T, Mowinckel MC, Abildgaard U. Thrombin-inhibitor complexes in the blood during and after delivery. Thromb Res. 1996;82:109–117. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(96)00057-6

125. Ku DH, Arkel YS, Paidas MP, Lockwood CJ. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha), resistance to activated protein C, thrombin and fibrin generation in uncomplicated pregnancies. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:1074–1079. doi:10.1160/TH03-02-0119

126. Faught W, Garner P, Jones G, Ivey B. Changes in protein C and protein S levels in normal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:147–150. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(95)90104-3

127. Lockwood CJ, Krikun G, Schatz F. The decidua regulates hemostasis in human endometrium. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1999;17:45–51. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1016211