Back to Journals » International Medical Case Reports Journal » Volume 12

Dermatitis artefacta: self-inflicted genital injury

Authors Olisova OY, Snarskaya ES, Smirnova LM, Grabovskaya O, Anpilogova EM

Received 28 October 2018

Accepted for publication 11 February 2019

Published 18 March 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 71—73

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S192522

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Ronald Prineas

O Yu Olisova, ES Snarskaya, LM Smirnova, O Grabovskaya, EM Anpilogova

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), 119991, Moscow, Russia

Background: The term dermatitis artefacta (factitious dermatitis, pathomimia) is reserved for the most severe variant of factitious physical disorder and is characterized by exaggerated lying (pseudologia fantastica), sociopathy, geographic wandering (peregrinating) from hospital to hospital, and seeking to be in the patient role.

Objective: This report aims to give attention to the importance of accurate and detailed history, and conducting an appropriate physical examination in patients with life-threatening diseases when the underlying cause is not apparent. The diagnosis of dermatitis artefacta must always be upheld.

Case presentation: We present a unique case of a 52-year-old male who presented to clinic with skin lesions on scrotum and shaft of his penis and that were very distinct and suggestive of pyoderma gangrenosum which he developed 3 months after previous discharge from the clinic. Clinical response to treatment and the absence of laboratory findings confirmed a dermatitis artefacta.

Conclusion: Dermatitis artefacta is a factitious disorder that involves falsification of psychological or physical signs or symptoms caused entirely by the patients themselves, in a clear state of consciousness, in order to play the role of a sick person. The correlation of anamnestic data and clinical and para-clinical exams was essential for the diagnosis of dermatitis artefacta in this case. To the best of our knowledge, pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions have never been reported in a patient with dermatitis artefacta. Herein, we describe a rare case report of self-inflicted genital injury in a 52-year-old male.

Keywords: factitious dermatitis, dermatitis artefacta, pathomimia, schizophrenia, pyoderma gangrenosum, contact dermatitis, herpes simplex, psoriasis

Introduction

Dermatitis artefacta (factitious dermatitis, pathomimia) is defined as the deliberate and conscious production of self-inflicted skin lesions to satisfy an unconscious psychological or emotional need or in order to play the role of a sick person mimicking any well-known dermatosis.1,2 It is characterized by geographic wandering from hospital to hospital, attraction to examinations, surgical operations, or seeking to find benefits.3 As a rule, its symptoms are the manifestation of the patient’s underlying psychiatric condition (severe psychopathy, endogenous and organic psychoses with affective disorders, delusion-like fantasies, paranoid-hallucinatory syndrome).4

An increase in incidence rate was registered for pathomimia in the USA (1% out of all hospitalized patients) and Germany (1.3%); further, 12.5% out of 1,545 patients who presented to our Department of Dermatology and Venereology (Sechenov University) during 3.5 months had psychodermatological disorders.5

We report on a patient with pathomimia, who had been unsuccessfully treated for pyoderma gangrenosum for several years.

Case report

A 52-year-old male presented to our department complaining of ulcerative defects on the internal surface of the hips, accompanied by pain and itching of the scrotum and shaft of the penis, progressing since the age of 47 (Figure 1A). He had no medical history before the age of 25, when he started to suffer from plaque psoriasis. At 30 years old, he developed vesicular lesions on the penis, and he was hospitalized for herpes simplex. He was treated with acyclovir 200 mg five times a day, with short-term clinical improvement and a herpes simplex vaccine, which led to a remission of 3 years. Six years ago, he was also successfully treated for psoriasis with methotrexate 100 mg, which however triggered recurrent herpes flare ups every 2 months. He used to open up the vesicles himself, which led to erosions. Due to his very distinct and suggestive skin lesions, the patient was long thought to have pyoderma gangrenosum, which was diagnosed by surgeons and was unsuccessfully treated with prednisone (40 mg/d) and infliximab (5 mg/kg), which was concomitantly added as a steroid-sparing agent with an induction regimen at 0, 2, and 6 weeks followed by a maintenance regimen every 8 weeks.

However, the lesions in the inguinoscrotal folds area had outlines implying that the skin had been cut with a knife. We also noticed that the lesions were found particularly in sites that were readily accessible to the patient’s hands. Furthermore, other patients suggested he had a persistent desire to manually manipulate his ulcers, and during a confidential conversation, he confessed that he had poured boiling water, followed by cold water, over the penis to stop the itching, achieving immediate relief. The patient was examined by a psychiatrist, who diagnosed schizophrenia, and it is important because those suffering schizophrenic behavior can easily conceal their true intentions and motives, answering questions without raising suspicion. Moreover, the patient was a veteran from the Afghanistan war, which had negatively affected his mental health (according to the psychiatrist’s conclusion).

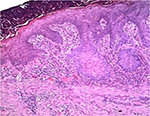

Based on histologic findings of the skin biopsy, which were characteristic for the simplest type of chronic inflammation (Figure 2), and psychiatric opinion, he was diagnosed with pyoderma secondary to dermatitis artefacta, and treated with rifampicin 300 mg twice daily and prednisone 25 mg/d. The corticosteroid dose was then tapered 2 mg once a week, until a dose of 8 mg/d was achieved, followed by a reduction in 2 mg steps every 2 weeks, until discontinuation. He also received an atypical antipsychotic (olanzapine 10 mg/d), psychotherapy, and occlusive dressings with an epithelizing ointment, which prevented him from perpetrating self-inflicting injuries (Figure 1B). The patient achieved significant improvement with the 4-week treatment with a complete healing through granulation and scarring of ulcers on the completion of the 24-week treatment (Figure 1C).

Conclusion

We believe that this case is noteworthy due to its unique clinical presentation, and demonstrates the importance of taking a detailed history, and conducting an appropriate physical examination in patients with life-threatening diseases, when the underlying cause is not apparent. In these difficult cases it is always important to keep in mind a possible diagnosis of dermatitis artefacta.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent has been provided by the patient to have the case details and all images published. No institution approval was required to publish the case details.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Koo JY, Do JH, Lee CS. Psychodermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 Pt 1):848–853. | ||

Jafferany M. Psychodermatology: a guide to understanding common psychocutaneous disorders. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(3):203–213. | ||

Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8(5):361–373. | ||

Koblenzer CS. Dermatitis artefacta. Clinical features and approaches to treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1(1):47–55. | ||

Ehsani AH, Toosi S, Mirshams Shahshahani M, Arbabi M, Noormohammadpour P. Psycho-cutaneous disorders: an epidemiologic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):945–947. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.