Back to Journals » Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology » Volume 8

Degos disease – malignant atrophic papulosis or cutaneointestinal lethal syndrome: rarity of the disease

Authors Pirolla E , Fregni F, Miura I, Misiara A, Almeida F, Zanoni E

Received 27 December 2013

Accepted for publication 13 August 2014

Published 16 April 2015 Volume 2015:8 Pages 141—147

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S59794

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Andreas M. Kaiser

Eduardo Pirolla,1 Felipe Fregni,1 Irene K Miura,2 Antonio Carlos Misiara,3 Fernando Almeida,3 Esdras Zanoni3

1Spaulding Rehabilitation Network Research Laboratory, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; 2University of São Paulo, Sirio Libanes Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil; 3Sirio Libanes Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil

Background: Degos disease is a very rare syndrome with a rare type of multisystem vasculopathy of unknown cause that affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. Other organs such as the kidneys, lungs, pleura, liver, heart, and eyes, can also be involved.

Objective: To highlight the incidence of Degos disease with regard to age and sex, discuss the necessity of its accurate and early diagnosis, and demonstrate the most current techniques for its diagnosis; to discuss whether early therapeutic intervention can impact patient prognosis; and to present a literature review about this disease.

Design: With a retrospective, observational, nonrandomized trial, we described the evolution of the different forms of Degos disease and referenced the literature.

Data sources: Research on rare documented cases in the literature, including two cases of potentially lethal form of the disease involving the skin and gastrointestinal system and, possibly, the lungs, kidneys, and central nervous system. A case of the benign form of the disease involving the skin was observed by the authors.

Main outcome measures: Differences between outcomes in patients with the cutaneointestinal form and skin-only form of the disease. There was one fatal outcome. We reviewed possible new approaches to diagnosis and treatment.

Results: The study demonstrated the rapid evolution of the aggressive and malignant form of the disease. It also described newly accessible Phase I diagnostic tools being currently researched as well as new therapeutic approaches.

Limitation: The rarity of the disease, with only eleven cases throughout the literature.

Conclusion: The gastrointestinal form of Degos disease can be lethal. Its vascular etiology has finally been confirmed; however, new and more accurate early diagnostic modalities need to be developed. There are new therapeutic possibilities, but the studies of them are still in the early stages and have not yet shown the full effectiveness of these new therapies.

Keywords: multisystem vasculopathy, diagnosis, lethal, gastrointestinal, Degos disease

Introduction

Degos disease most frequently presents in white male teenagers, with the initial symptom being skin lesions on the trunk (Figure 1). Sometimes, within days, the patient presents with generalized acute abdominal pain and fever. Patients in this situation are frequently treated with surgery (exploratory laparotomy). Patients experience frequent vomiting and abdominal distension that does not improve after surgery. Weight loss at an average of 6–10 kg per month is common. A repeat laparotomy is frequently performed because of intestinal occlusion by adherences or acute peritonitis. Persistent high fevers, abdominal pain, and gastroparesis are very common in these cases.

| Figure 1 Initial skin lesions in Degos disease. |

At the time of admission, fever (100.4°F–104.0°F), normal blood pressure, and sinus tachycardia are frequent. Peritonitis and septicemia should be suspected. In progressive conditions of the disease, multiple lesions with a papular aspect are observed in the thorax wall, abdominal wall, and limbs.

Blood tests reveal an elevated white blood cell count (normally of more than 30,000 cells/mm3) and low levels of hemoglobin and platelets because of infection. Blood gases show respiratory alkalosis with concomitant metabolic acidosis in most cases.

Chest and abdominal computerized tomography (CT) can reveal pleural effusion in the lower lungs fields and free liquid in the abdominal cavity with an edematous bowel aspect. Paralytic ileum can be present.

Laparotomy is always indicated and can show lesions consisting of white and yellowish or pearly-rose patches (Figure 2A) with a hyperemic rim throughout the bowel, mainly in the gastrointestinal tract. One or more points of perforation can commonly be observed in the jejunum, ileum, and colon, resulting in intestinal resections (Figure 2B).

| Figure 2 White/yellowish lesions and ileal, duodenal, and gastric perforations. |

Microscopic examination can reveal poor lymphomononuclear infiltrate and no granulomatous process, vasculitis, or neoplastic involvement.

A second-look operation is commonly performed 48 hours after the first laparotomy because of the frequent occurrence of new abdominal pain and an improvement in the inflammatory conditions. A skin biopsy is important for the diagnosis of Degos disease and will exhibit epidermal atrophy and dermal sclerosis with or without vasculitis. However, the histological findings of the intestinal and skin lesion biopsies may be inconclusive.

The diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s disease, frequently requires discussion of the case by multiple doctors. Corticoids, such as methylprednisolone, are the first drug that doctors use in these patients.

Many repeat laparotomies are performed because of abscesses observed on control CTs.

A dermatological evaluation of skin lesions from multiple body locations (Figures 3 and 4) may encourage new skin microscopic examinations and may reveal an expressive papillary dermal sclerosis and thrombosis in the papillary dermis and in the vessels below the lesions.

| Figure 3 Skin lesions, typical aspect with necrosis, fibrin and deep lesions. |

| Figure 4 Skin lesions, characteristic aspect of deep lesions and diffuse distribution. |

With these histopathological findings and clinical/surgical aspects patients can be diagnosed with Degos disease. Antiplatelet therapy (acetylsalicylic acid) may be initiated and can be given in combination with steroid therapy. Pentoxifylline and heparin should also be given. Interleukin, interferon and infliximab can also be added to the treatment. As studies have shown that vasculitis is the initial skin condition of Degos disease. The objective of those research models was to select drugs that block the deleterious autoimmune response in the blood vessels (Figure 5).1

| Figure 5 An experimental mouse model of autoimmune pancreatitis, which is a T-cell-mediated disease. |

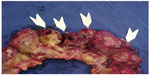

New perforations and bowel necrosis can occur, making new resections, enterectomies, and stomas necessary (Figures 6 and 7).

| Figure 6 Diffuse ileal and colonic lesions and perforations. |

| Figure 7 Diffuse ileal and colonic lesions and perforations (arrows). |

Microscopic examination will reveal diffuse transmural ulcerations and punctate perforations associated with an occlusive fibrosis of the medium- and small-diameter arteries and veins. Vessels are often occluded by thrombosis.

Uncontrollable septicemia and persistent gastrointestinal bleeding associated with renal failure and cerebral vascular lesions are the most common causes of death in patients with Degos disease.

The median period of survival for these patients is no longer than 6 months.

Results

Between June 1, 1998, and December 23, 2008, three cases of Degos disease were recorded, one case of the cutaneous or benign form and two cases of the cutaneous intestinal or malignant form. In 2013, a retrospective study of Degos disease cases was conducted, which revealed a permanent lethality of the malignant form of the disease. It also showed a favorable evolution, with greater than a 20% survival rate of the benign form of the disease.2

The retrospective study demonstrated the rapid evolution of the aggressive and malignant form of the disease, as well as newly accessible diagnostic tools, diagnostic tools currently being researched in Phase I trials, and new therapeutic approaches.

Limitation

The main limitation to this study is based on the rarity of the disease, with only eleven cases described throughout the world medical literature.

Discussion and systematic review

Degos disease, also known as Köhlmeier–Degos disease and malignant atrophic papulosis (MAP), is a rare vasculopathy of unknown cause that mainly involves the skin, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, and, occasionally, other organs. It was first named by Degos et al3 in 1942, but a case was reported in 1941 by Köhlmeier,4 who interpreted it as thromboangiitis obliterans of the mesenteric vessels. Although this disease usually affects young people, with an age of onset between 20 and 40 years, it may present at any age, even as early as 8 months.5,6 The disease has a male predominance (3:1), and sporadic cases of familial involvement have been recorded.5–9 The involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and other organs has been noted in approximately 60% of reported cases.10

Degos disease is a truly systemic illness, and at autopsy, lesions may be found in multiple sites, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, bladder, eyes, liver, and genital and oral mucosa.11–16 However, in a subgroup of patients, the disorder may pursue a benign course involving only the skin for many years.15 Skin lesions are usually the first sign of the disease.5 The disease has been reported to be purely cutaneous in 37% of patients.17 Clinically, one sees pink- to rose-colored papules that may appear telangiectatic and are in different stages of development. Early lesions are slightly darker, may have an elevated border, and exhibit a central porcelain-white depression. The lesions are asymptomatic (except in a few cases in which they have appeared pruritic), benign and predominantly appear on the trunk and extremities.5,18

The lesions affect the bowel in approximately 47% of cases. Intestinal symptoms are variable, although any portion of the intestinal system (from the oral cavity to the anus) may be involved, and the small bowel is predominantly affected. Lesions of the gastrointestinal tract are most often associated with skin involvement.15,16,18 In rare cases, a bowel injury may precede cutaneous signs, hampering the diagnosis.14,19 Some patients are asymptomatic, but others may complain of indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, and symptoms of gastroparesis or abdominal distension.15,20

Many patients are asymptomatic, and abdominal involvement may be uncovered by systematic investigations, including endoscopy (visualizing white, yellowish, or pearly-rose patches with a hyperemic rim resembling the skin lesions but larger in size), laparoscopy (showing a comparable aspect on parietal and visceral peritoneum), and angiography (showing multiple stenoses of branches of the inferior mesenteric artery and hypovascular zones on delayed pictures).18,21–23 Multiple red inflammatory and white atrophic maculae can be observed on the serosa of the small and large intestines, and a section of the removed specimen can show acute inflammation and ulceration of the mucosa with surrounding intense congestion.15 Of greater importance, a small infarction of the intestine may develop and cause perforation and resultant peritonitis.24,25 To avoid fistulous problems, biopsies of the bowel wall should never be taken. Instead, biopsies of the parietal peritoneum lesions should be taken.18

Neurological involvement occurs in 19% of cases.16,26–28 The manifestation of neurological involvement is highly variable, but hemiparesis with or without aphasia, monoplegia, tetraplegia, and cranial nerve involvement have been found. Cases of ascending polyradiculitis or myelomalacia have been reported. Headache, mental dysfunction, and weakness of the limbs are also common. Sometimes, injuries of the whole eye may be observed.16,28

The diagnosis of Degos disease is based on the following clinicopathologic finding: many papules, 2–5 mm in diameter, with the classic porcelain-white centers characteristic of Degos disease. Some cases have exhibited different clinical morphologies that corresponded to the evolutionary stages of the papules originally described by Degos. Histologically, those patients exhibited a preeminent interface reaction with squamatization of the dermo–epidermal junction, melanin incontinence, epidermal atrophy, and a developing zone of papillary dermal sclerosis that resembled the early stages of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, in miniature. This interface reaction was invariably confined to the central portion of the punch biopsy specimen, corresponding to the central porcelain-white area observed clinically. Additional features of fully developed papules included a prominent lymphocytic vasculitis affecting the venules, a mild periadnexal infiltrate of neutrophils and/or eosinophils, and interstitial mucin deposition. According to Harvell et al, these inflammatory cells are sometimes absent.29 In late-stage papules, the porcelain-white areas are more developed and the lesions are flattened. Histologically, the degree of inflammation was generally sparse, and the overall picture mirrored the classic histological description of Degos disease with a central roughly wedge-shaped zone of sclerosis surrounded by atrophic epidermis and hyperkeratotic compact stratum corneum.30 Skin lesions typically occur on the trunk and limbs. The palm, soles, face, and scalp are characteristically free of lesions.16,28

The accurate etiology of Degos disease is still unclear, although viral, genetic, and immune mechanisms and an anomalous fibrinolysis have all been implicated. The pathogenesis of Degos disease is still under discussion, but primary endothelial swelling with vascular thrombosis leading to tissue infarction has been proposed. The cause of the initial vascular injury is unknown, but a mononuclear vasculitis seems to be the favored mechanism.28 It is possible for Degos disease to be associated with other systemic diseases.31 Its differential diagnosis is poor, as the cutaneous lesions are pathognomonic. Yet systemic lupus erythematosus and inflammatory bowel disease may occasionally be discussed.32,33

Approximately 15% of Degos disease patients exhibit long-term survival, with the disease often limited to the skin and with no history of catastrophic bowel or central nervous system involvement. When there is multiple organ involvement, the disease results in death within 2–3 years.15 The course of the disease may be as long as 20 years, but once intestinal lesions have appeared, death usually occurs within a few months. The most common causes of death are peritonitis (61%), central nervous system complications (18%), and pleuritis and/or pericarditis (16%).17

There is no proven effective treatment for patients with systemic involvement.23 Treatment with plasma change, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or antiinflammatory drugs has been ineffective in reversing the course of this disease when systemic involvement is present.15,34,35 Some authors have reported a good response to antiplatelet therapy.10,11,36,37 A publication from Japan in January 2013 showed the expression of stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1/CXCL12 in Degos disease. Secretory activity by stromal and endothelial cells of the bone marrow activates SDF-1/CXCL12 of megakaryocyte precursors and is responsible for the costimulation of platelet activation. Patients with Degos disease demonstrated a high level of secretion of SDF-1/CXCL12 inflammatory cells. This cell type was located in the perivascular, intravascular, and perineural tissue. These results support the theory that Degos disease is an endothelial disease.38,39

Conclusion

The gastrointestinal form of Degos disease remains a serious and lethal disease. The vascular etiology of this disease has finally been confirmed; however, new and more accurate early diagnostic modalities need to be developed. There are new therapeutic possibilities; however, studies of new treatments are still in the early stages and the full effectiveness of those treatments has not been shown.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Schwaiger T, van den Brandt C, Fitzner B, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis in MRL/Mp mice is a T-cell-mediated disease responsive to cyclosporine A and rapamycin treatment. Gut. 2014;63(3):494–505. | |

Moulin G. Les formes benignes de la papulose atrophiante maligna de Degos. [Benign forms of Degos’ malignant atrophic papulosis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1988;115:1289–1290. French. | |

Degos R, Delort J, Tricot R. [Dermatite papular atrophicans]. Dermatite papulo-squameuse atrophiante. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1942;49:148–281. Portuguese. | |

Köhlmeier W. [Multiple skin necrosis in thromboangiitis obliterans]. Multiple Hautnekrosen bei Thromboangiitis obliterans. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1941;181:792–793. German. | |

Degos R. Malignant atrophic papulosis. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:21–35. | |

González JA, Noguer S, Cabré J. Papulosis atrofiante maligna de Degos (observacion de um caso afectando a um lactante). [Degos’ malignant atrophic papulosis (observation of a case in an infant)]. Actas Drmosifiliogr. 1975;66(5–6):317–319. Spanish. | |

Habbema L, Kisch LS, Starink TM. Familial malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease) – additional evidence for heredity and a benign course. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:134–135. | |

Kisch LS, Bruynzeel DP. Six cases of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease) occurring in one family. Br J Dermatol. 1984;111:469–471. | |

Newton JA, Black MM. Familial malignant atrophic papulosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:298–299. | |

Vicktor C, Schultz-Ehrenburg U. Papulosis maligna atrophicans (Köhlmeier–Degos): Diagnose, Therapie, Verlauf. [Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos): diagnosis, therapy and course]. Hautarzt. 2001;52:734–737. German. | |

Yukiiri K, Mizuzhige K, Ueda T, et al. Degos’ disease with constrictive pericarditis: a case report. Jpn Circ J. 2000;64:464–467. | |

Pierce RN, Smith GJ. Intrathoracic mainifestations of Degos’ disease (malignant atrophic papulosis). Chest. 1978;73:79–84. | |

Bjorcks S, Johansson SL, Aurell M. Acute renal failure caused by a rapidly progressive arterio-occlusive syndrome – Köhlmeier-Degos’ disease? Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1984;18:343–346. | |

Lankisch MR, Johst P, Scolapio JS, Fleming CR. Acute abdominal pain as a leading symptom for Degos’ disease (malignant atrophic papulosis). Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1098–1099. | |

McKee PH. Vascular disease. In: McKee PH, editor. Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations. London, England: Mosby-Worfe; 1996:5.33–35.34. | |

Magrinat G, Kerwin KS, Gabriel DA. The clinical manifestations of Degos’ syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113:354–362. | |

Burg G, Vieluf D, Stolz W, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis. Hautarzt. 1989;40:480–485. | |

Valverde FMG, Pina FM, Ruiz JA, et al. Presentation of Degos syndrome as acute small-bowel perforation. Arch Surg. 2003;138:57–58. | |

Amaravadi RR, Tran TM, Altman R, Scheirey CD. Small bowel infarcts in Degos disease. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33(2):196–199. | |

Beales IL. Malignant atrophic papulosis presenting as gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3462. | |

Casparie MK, Meyer JW, van Huystee BE, Kneppelhout J, Mulder CJ. Endoscopic and histopathologic features of Degos’ disease. Endoscopy. 1991;23:231–233. | |

Bilbao JI, Garcia Delgado F, Idoate M, Aréjola JM, Aquerreta D, Otero M. Maladie de Degos. Atteinte intestinale mise en évidence par angiographie numérique: Un cas. [Degos’ syndrome. Intestinal involvement as demonstrated by digital angiography. A case]. J Radiol. 1986;67(10):711–713. French. | |

Paolaggi JA, Daniel F, Mugnier B, Debray C. Manifestations digestives de la papulose atrophiante maligne (maladie de Degos). Intérêt de laparoscopie. [Digestive manifestations of malignant atrophying papulosis (Degos’ disease). Value of laparoscopy]. Ann Méd Interne. 1970;121:965–969. French. | |

Barrière H, Welin J, Bureau B, Pannier M. Papulose atrophiante maligne, avec peritonite par diffusion. [Malignant atrophic papulosis with diffuse peritonitis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1977;104:162. French. | |

De Leo G, Losacco T, Punzo C, et al. Su un caso di papulosiatrofica maligna (P.A.M.) o malattia di Degos. [Report of a case of malignant atrophic papulosis or Degos disease]. G Chir. 1994;15:97. Italian. | |

Rosemberg S, Lopes MB, Sotto MN, Graudenz MS. Childhood Degos’ disease with prominent neurological symptoms: report of a clinicopathological case. J Child Neurol. 1988;3:42–46. | |

Barlow RJ, Heyl T, Simson IW, Schulz EJ. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos’ disease) – Diffuse involvement of brain and bowel in an African patient. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:117–123. | |

Winkelmann RK, Howard FM, Perry HO, et al. Malignant papulosis of skin and cerebrum. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:54–62. | |

Harvell JD, Williford PL, White WL. Benign cutaneous Degos’ disease: a case report with emphasis on histopathology as papules chronologically envolve. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23(2):116–123. | |

Trible K, Archer ME, Jorizzo JL, et al. Malignant atrophic papulosis: absence of circulating immune complexes or vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:365–369. | |

Durie BGM, Stroud JD, Kahn JA. Progressive systemic sclerosis with malignant atrophic papulosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:575–581. | |

Atchabahian A, Laisné MJ, Riche F, Briard C, Nemeth J, Valleur P. Small bowel fistulae in Degos’ disease: a case report and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;10:2208–2210. | |

Scully RE, Galdabini JJ, McNeely BU. Case reports of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 44-1980. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1103–1111. | |

Beuran M, Chiotoroiu AL, Morteanu S, et al. Köhlmeier-Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis): a cause of recurrent multiple intestinal perforations. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2009;104(6):765–772. | |

Wilson J, Walling HW, Stone MS. Benign cutaneous Degos disease in a 16-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24(1):18–24. | |

Shapiro LS, Toledo-Garcia AE, Farrell JF. Effective treatment of malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) with treprostinil – early experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8(1):52. | |

Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease) – a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8(1):10. | |

Scheinfeld N. Commentary on ‘Degos disease: a C5b-9/interferon-α-mediated endotheliopathy syndrome’ by Magro et al: a reconsideration of Degos disease as hematologic or endothelial genetic disease. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(8):6. | |

Meephansan J, Komine S, Hosoda S, et al. Possible involvement of SDF-1/CXCL 12 in the pathogenesis of Degos disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(1):138–143. | |

Ray K. Pancreatitis: T cells have a pivotal role in autoimmune pancreatitis in an experimental mouse model. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(6):321. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.