Back to Journals » Hepatic Medicine: Evidence and Research » Volume 9

Decreasing racial disparity with the combination of ledipasvir–sofosbuvir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C

Authors Naylor PH, Mutchnick M

Received 5 December 2016

Accepted for publication 8 February 2017

Published 16 March 2017 Volume 2017:9 Pages 13—16

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HMER.S118063

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Gerry Lake-Bakaar

Paul H Naylor , Milton Mutchnick

Department of Internal Medicine/Gastroenterology, Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA

Abstract: African Americans (AA) in the US are twice as likely to be infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) compared to the non-Hispanic-white US population (Cau). They are also more likely to be infected with HCV genotype 1, more likely to develop hepatocellular carcinoma, and, in addition, have a lower response rate to interferon-based therapies. With the increase in response rates reported for combinations of direct-acting antivirals, the possibility that racial disparity would be eliminated by agents that directly inhibit virus replication has become a reality. The objective of this review is to evaluate the literature from clinical studies and retrospective analysis with respect to the response of AA to the most prescribed antiviral combination sofosbuvir plus ledipasvir. While few studies have focused on AA patients, sufficient information is availed from the literature and studies in our predominately AA clinic population to confirm that ledipasvir–sofosbuvir has a similar effectiveness in AA as compared to Cau.

Keywords: hepatitis C, African Americans, ledipasvir, sofosbuvir, Harvoni, direct acting antivirals

Introduction

More than 130 million people worldwide (~3%) and 3.2 million in the US are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and thus exposed to significant risk of developing HCV-related morbidity and mortality.1–5 African Americans (AA) in the US are twice as likely to be infected with HCV compared to the non-Hispanic-white US population (Cau) (3% vs 1.5%), more likely to be genotype 1, more likely to develop hepatocellular carcinoma, and, in addition, have a lower response rate to approved interferon-based therapies.6–16 Studies focusing on this population have provided useful information with respect to the efficacy of new therapies and decisions to treat this historically low response rate group. Such studies are of importance, since many clinical trials overestimate the response of AA patients treated in community settings. One reason for this is that clinical trials often do not include large numbers of AA since they represent only 13% of the population.17 Thus, pooling of the patients from multiple trials, if possible, may often be required to generate significant numbers of AA patients. For example, it was only after pooling of clinical trial patients that first generation direct-acting antiviral (DAA) triple therapy (telaprevir/boceprevir + interferon, and ribavirin) was shown to be better than dual therapy (interferon and ribavirin) for both races, but AA patients still had a lower response than Caucasians.10 These observations were recently confirmed in a study by Naylor et al12 in a “real world” clinic setting, where the predominant population being treated was AA.

While this racial disparity has been frustrating for the physicians who treat predominately AA populations, the increased response seen with first generation DAA was heartening, and the development of DAA therapies that did not rely on interferon or ribavirin offered even more hope. The objective of this review is to evaluate the response of predominately AA population to the most widely prescribed DAA therapy to date: ledipasvir–sofosbuvir (Harvoni).

Methods

Two types of data were collected for this review. The first was from the published literature of AA response in studies using a combination of ledipasvir–sofosbuvir. Using a search of PubMed with the terms ledipasvir–sofosbuvir and AA, five research studies and one meta-analysis review were identified.18–23 Four of the studies utilized the same VA database and either were updated with additional patients or evaluated the patient data set in slightly different ways. The data from two of the published studies are included in this review.19,20

The second set of data came from the medical records of all patients treated with ledipasvir–sofosbuvir (Harvoni) at the Wayne State University (WSU) Gastroenterology Practice, where the majority of patients with Hepatitis C are AA. Data from the medical records of patients treated from August 2011 to March 2016 were included in an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved study. The Wayne State University Institutional Review Board operates under United States Department and Human Services Federal Wide Assurance, and the identification number is FEA00002460. The IRB approval number for the study is 111511MP2E. The patient data were gathered under a waiver of HIPAA Authorization granted in accordance with the Privacy Rule and justification provided by the Principal Investigator that the use of data involved minimal risk and the research could not be performed without access to PHI for a large number of patients such that informed consent could not be practically obtained.

Response rate to therapy was calculated as intent to treat, and sustained viral response was defined as a negative HCV PCR assay 12 weeks after completion of therapy.

Results

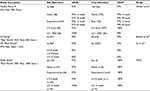

Table 1 presents a summary of the data from the literature and the WSU study with respect to ledipasvir–sofosbuvir comparing Caucasian to AA responses.

There were several significant findings in the Phase 3 data pooling study that assessed patients from the three ION studies. With respect to demographics, the AA population was slightly older and had higher body mass index and lower serum alanine aminotransferase at baseline as compared to non-AA patients. The overall response rates were similar (95% AA vs 97% Cau). There was also no significant difference in race with 12 or 24 weeks of treatment. Previously treated or naïve patients did not show a racial difference, and the addition of ribavirin was not required in either race.

The first VA study (Backus et al20) utilized the VA records and was thus real world, observational, and retrospective. Patients were treated for either 8 weeks or 12 weeks based on guidelines. While the response rate was slightly lower than the pooled clinical data, the patients in the VA study were all genotype 1, and the racial differences were minimal. The major racial difference was that AA were more likely to discontinue or be noncompliant as compared to non-AA, and this was reflected in the intent to treat analysis. The VA study also included a significant number of patients who could be qualified as having advanced liver, based primarily on the FIB-4 or APRI values. While not biopsy-proven cirrhotic, the absolute sustained viral response was 4%–5% lower than patients without advanced disease. A similar observation was found for patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 as compared to those with a BMI <30. The authors suggest that a 24-week course be considered for patients with advanced liver disease and those with a BMI >30. In the second VA study (Su et al21), the number of patients studied was higher, and the results were similar with respect to the overall response rates being similar to the registration clinical trials and the AA patient response being similar to that for Caucasians. The most significant difference in response rates was when AA were compared to Cau patients treated for 8 weeks vs 12 weeks.

In the WSU study, response rates of AA patients were similar to those reported in the pooled clinical trials and the VA study. The four patients who failed combination DAA were instructive and consistent with the literature. One patient was noncompliant, one stopped early owing to diarrhea, one had a history of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and had previously failed triple therapy, and the fourth was an AA patient with HIV, who relapsed after termination of therapy.

With respect to safety, no overall differences were identified between races in any of the studies.

Discussion

The use of dual DAA, such as Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir (Harvoni), has essentially eliminated the racial bias of the previous interferon-based therapies. This was demonstrated in a clinical trial setting by a study that pooled the data from clinical trials to compare 308 AA to 1641 non-AA. This was also demonstrated in two VA studies combining data from approximately 124 VA medical centers. While predominately male, the retrospective studies had significant numbers of AA patients and confirmed the clinical trial observation in a “real world” setting. Finally, in a single center study at the Wayne State University, high real world responses of AA to dual antivirals were also demonstrated. Thus, both in clinical trials and in real world treatment studies, high response rates that were similar between Cau and AA have been demonstrated. Of note is that the only caveat to treating AA patients based on the VA and WSU studies is that a 12-week regimen appears to be more effective than an 8-week treatment protocol, and although not yet in the guidelines for non-HIV-infected patients, it is clearly in the category of being a literature-supported recommendation.

Using agents that directly target the HCV replication and do not rely on host factors as did interferon-based therapy has been the primary reason that high treatment rates are seen for both Cau and AA patients with hepatitis C. Based on these recent studies, it is reasonable to counsel AA patients that response rates greater than 95% are likely and that these can be achieved with 8–12 weeks of one pill a day and with minimal side effects. These success rates also appear independent of compensated cirrhosis and previous treatment failure. While response rates are rapid and high, suggesting that these are powerful antivirals and the side effects are minimal, compliance remains a key component of efficacy.

Disclosure

Dr Mutchnick is a speaker for Gilead Sciences and, with Dr Naylor, has received investigator-initiated research grants from Gilead Sciences. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Averhoff FM, Glass N, Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(Suppl 1):S10–S15. | ||

Ward JW. The hidden epidemic of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: occult transmission and burden of disease. Top Antivir Med. 2013;21(1):15–19. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23596274. | ||

Maasoumy B, Wedemeyer H. Natural history of acute and chronic hepatitis C. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26(4):401–412. | ||

Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333–1342. | ||

Kanwal F, Hoang T, Kramer JR, et al. Increasing prevalence of HCC and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(4):1182–1188.e1. | ||

Jeffers LJ. Treating hepatitis C in African Americans. Liver Int. 2007;27:313–322. | ||

Karoney MJ, Siika AM. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Africa: a review. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14:44. | ||

Kinzie JL, Naylor PH, Nathani MG, et al. African Americans with genotype 1 treated with interferon for chronic hepatitis C have a lower end of treatment response than Caucasians. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8(4):264–269. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11454177. Accessed July 17, 2014. | ||

Jin R, Cai L, Tan M, Mchutchison JG, Thomas C, Howell CD. Optimum ribavirin exposure overcomes racial disparity in efficacy of peginterferon and ribavirin treatment for hepatitis C Genotype 1. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1675–1683. | ||

Flamm SL, Muir AJ, Fried MW, et al. Sustained virologic response rates with telaprevir-based therapy in treatment-naive patients evaluated by race or ethnicity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(4):336–344. | ||

Walzer N, Flamm SL. Pegylated IFN-α and ribavirin: emerging data in the treatment of special populations. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2009;2(1):67–76. | ||

Naylor P, Alebouyeh N, Mutchnick S, et al. Interferon (IFN) based treatment of African Americans with Chronic Hepatitis C (CHC) in an Urban Clinic: improving response with advances in therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2015;4(2):1465–1469. | ||

Howell C, Jeffers L, Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis C in African Americans: summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1385–1396. | ||

El Serag HB, Mason A. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745–750. | ||

Pyrsopoulos N, Jeffers L. Hepatitis C in African Americans. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:185–193. | ||

Mir HM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Kugelmas M, Younossi ZM. African Americans are less likely to have clearance of hepatitis C virus infection: the findings from recent U.S. population data. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:e62–e65. | ||

Wilder J, Saraswathula S, Saddelblad V, Muir A. A systematic review of race and ethnicity in Hepatitis C clinical trial enrollment. J Nat Med Assoc. 2016;108:24–29. | ||

Toussaint-Miller KA, Andres J. Treatment considerations for unique patient populations with HCV Genotype 1 infection. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(9):1015–1030. | ||

Wilder JM, Jeffers LJ, Ravendhran N, et al. Safety and efficacy of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in black patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a retrospective analysis of phase 3 data. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):437–444. | ||

Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Loomis TP, Mole LA. Effectiveness of sofosbuvir-based regimens in genotype 1 and 2 hepatitis C virus infection in 4026 U.S. Veterans. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(5):559–573. | ||

Su F, Green PK, Berry K, Ioannou GN. The association between race/ethnicity and the effectiveness of direct antiviral agents for hepatitis C virus infection. Heptology. 2017;65(2):426–438. | ||

Ioannou GN, Beste LA, Chang MF, et al. Effectiveness of Sofosbuvir, Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir, or Paritaprevir/Ritonavir/Ombitasvir and Dasabuvir regimens for treatment of patients with hepatitis C in the Veterans Affairs National Health Care System. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(3):457–471.e5. | ||

Fox DS, McGinnis JJ, Tonnu-Mihara I, McCombs JS. Comparative treatment effectiveness of direct acting antiviral regimens for hepatitis C: data from the Veterans Administration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. Epub 2016 Nov 21. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.