Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 12

Correlation between HLA haplotypes and the development of antidrug antibodies in a cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases

Authors Benucci M, Damiani A, Li Gobbi F , Bandinelli F, Infantino M, Grossi V, Manfredi M, Noguier G, Meacci F

Received 10 July 2017

Accepted for publication 19 October 2017

Published 31 January 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 37—41

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S145941

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Maurizio Benucci,1 Arianna Damiani,1 Francesca Li Gobbi,1 Francesca Bandinelli,1 Maria Infantino,2 Valentina Grossi,2 Mariangela Manfredi,2 Guillaume Noguier,3 Francesca Meacci2

1Rheumatology Unit, 2Immunology and Allergology Laboratory Unit, USL-Toscana Centro, Hospital S. Giovanni di Dio, Florence, Italy; 3Theradiag, Croissy Beaubourg, France

Introduction: The aim of this study was to investigate the correlation between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes and the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs) in a cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases.

Patients and methods: We evaluated the presence of ADAs in 248 patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases after 6 months of treatment with anti-TNF drugs: 26 patients were treated with infliximab (IFX; three with rheumatoid arthritis [RA], 13 with ankylosing spondylitis [AS], 10 with psoriatic arthritis [PsA]); 83 treated with adalimumab (ADA; 24 with RA, 36 with AS, 23 with PsA); 88 treated with etanercept (ETA; 35 with RA, 27 with AS, 26 with PsA); 32 treated with certolizumab (CERT; 25 with RA, two with AS, five with PsA); and 19 treated with golimumab (GOL; three with RA, seven with AS, nine with PsA). Serum drug and ADA levels were determined using Lisa-Tracker Duo, the ADA-positive samples underwent an inhibition test, and the true-positive samples underwent genetic HLA typing. To have a homogeneous control population, we also performed genetic HLA typing of 11 ADA-negative patients.

Results: After inhibition test, the frequency of ADAs was 2/26 patients treated with IFX (7.69%), 4/83 treated with ADA (4.81%), 0/88 treated with ETA (0%), 4/32 treated with CERT (12.5%), and 1/19 treated with GOL (5.26%). The frequency of HLA alleles in the examined patients was HLA-DRβ-11 0.636, HLA-DQ-03 0.636, and HLA-DQ-05 0.727. The estimated relative risks between the ADA-positive patients and the ADA-negative patients were HLA-DRβ-11 2.528 (95% CI 0.336–19.036), HLA-DQ-03 1.750 (95% CI 0.289–10.581), and HLA-DQ-05 2.424 (95% CI 0.308–15.449).

Conclusion: This is the first study that shows an association between HLA and genetic factors associated with the occurrence of ADAs in patients with rheumatic diseases, but the number of samples is too small to draw any definite conclusion.

Keywords: antidrug antibodies, HLA haplotypes, rheumatic diseases

Introduction

The introduction of anti-TNF drugs has benefited many patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but, in some cases, the drugs trigger an immune response that leads to the development of antidrug antibodies (ADAs), one of the causes of a clinical nonresponse to treatment with infliximab (IFX) or adalimumab (ADA) that has also been described in patients with Crohn’s disease.1,2 Many factors that can affect immunogenicity include disease activity, drug dose and dosing schedule, the route of administration, concomitant medications (including immunosuppressants), and genetic background.3

It is difficult to identify the genetic factors associated with the development of ADAs because of the large number of patients necessary for this type of study, and only one study of the influence of genetic variation on immunogenicity of anti-TNF agents has been published so far. This study found a correlation between the IL10 genotype and the production of ADA ADAs, but the causality of this relationship requires further investigation.4 Drug-related factors can also influence the immunogenicity of a biological agent as differences in amino acid sequences between therapeutic and endogenous proteins promote the formation of ADAs, drugs with epitopes that bind to B or T cells have greater immunogenic potential, and the structural properties of a therapeutic protein can also increase the risk of an immune reaction.5–7

The aim of this study was to analyze the association between human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes and the development of ADAs in a cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases.

Patients and methods

We evaluated 248 Caucasian rheumatic patients after 6 months of treatment with anti-TNF drugs, of whom 26 were treated with IFX (three with RA, 13 with ankylosing spondylitis [AS], 10 with psoriatic arthritis [PsA]); 83 treated with ADA (24 with RA, 36 with AS, 23 with PsA); 88 treated with etanercept (ETA; 35 with RA, 27 with AS, 26 with PsA); 32 treated with certolizumab (CERT; 25 with RA, two with AS, five with PsA); and 19 treated with golimumab (GOL; three with RA, seven with AS, nine with PsA). Characteristics of patients at baseline with disease activity score for the respective three diseases and the concomitant use of Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug (DMARD) are specified in Table 1. Serum drug and ADA levels were determined using Lisa-Tracker Duo (Theradiag, Croissy Beaubourg, France), the ADA-positive samples underwent an inhibition test, and the true-positive samples and 11 ADA-negative samples underwent genetic HLA typing.

All patients signed a written consent to be evaluated for the HLA genotyping. The consents are physically conserved in the Genetic Unit of the Hospital. All patients gave their written informed consent to this retrospective study according to the Declaration of Helsinki and to Italian legislation (Authorization of the Privacy Guarantor No. 9, December 12, 2013). The institutional review board, the Health Director of San Giovanni di Dio Hospital in Florence, reviewed and approved this study and the use of clinical and laboratory data of common clinical practice, with respect to privacy law, for clinical and scientific studies and publications.

Drug levels

Drug levels were determined using Lisa-Tracker Duo, an enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) for the quantitative determination of drug levels in human serum samples. TNF-α was coated onto a polystyrene microtiter plate (six rows of eight wells), and the diluted sample was added to allow binding; after incubation, the unbound proteins were removed by washing. Subsequently, biotinylated antihuman IgG antibodies were added and, after incubation, the unbound antibodies were removed by washing. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin was then added, and bound to the complex formed by the biotinylated anti-IgG antibodies. After incubation, the wells were washed once again to eliminate any excess conjugate, and the bound enzyme was revealed by adding a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (the intensity of the color was proportional to the amount of drug). The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 0.25 of H2SO4, and the optical density was read by means of a spectrophotometer at 450 nm. A calibration range allowed the quantity of drug in each sample to be expressed in micrograms per milliliter.

ADAs

Lisa-Tracker Duo was also used to evaluate ADAs. Depending on the dosage, the drug was coated onto a polystyrene microtiter plate (six rows of eight wells), and the diluted sample was added to the antibody-coated wells to allow binding; after incubation, the unbound proteins were removed by washing. The biotinylated drug was then added and, after incubation, the unbound antibodies were removed by washing. Subsequently, horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin was added and bound to the complexes formed by the biotinylated drugs. After incubation, the wells were washed again to eliminate any excess conjugate, and the bound enzyme was revealed by adding a TMB substrate (the intensity of the color was proportional to the amount of ADAs). The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 0.25 of H2SO4, and the optical density was read by means of a spectrophotometer at 450 nm. A calibration range allowed the quantity of ADAs in each sample to be expressed in nanograms per milliliter.

ADA inhibition

An aliquot of each serum sample was diluted 1:2 in dilution and wash buffer (TDL), and in parallel, another aliquot of the same sample was diluted 1:2 in TDL with the addition of drug at a concentration of 100 µg/mL. All the diluted samples were incubated 1 hour at room temperature, and then vortexed. After this incubation, 100 mL of the standards, diluted positive controls, and diluted serum samples were added to the microplate wells and assayed using the Lisa-Tracker ADA kit as described earlier. After reading the optical density of each well at 450 nm, the percentage of inhibition in the samples in the presence of 100 mg/mL of drug was calculated as follows: inhibition (%) = 100 × 1 – (the result from the drug-spiked sample/result from the unspiked sample). A sample showing >50% inhibition can be considered truly positive for ADAs.

HLA genotyping

HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRβ1, and HLA-DQβ1 were genotyped by means of the hybridization of sequence-specific oligonucleotide (SSO) probes immobilized on microspheres and amplified genomic DNA samples, followed by flow fluorescence intensity analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA, USA). In the validation study cohort, the HLA analysis was restricted to HLA-DRβ1*11 and HLA-DQ-03-05. The presence or absence of the haplotypes was determined using nested sequence-specific primer polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-SSP. In both cohorts, HLA-DRβ1*11 alleles were identified by means of the group-specific sequencing of exon 2 of the HLA-DRβ1*11-positive samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HLA was classified using serological techniques to broad antigens and splits, with the classic methodical National Institutes of Health (NIH) in microlymphocytotoxicity according to Terasaki and McClelland,8 with the trade plates, antigens for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DR, and HLA-DQ. In 201 donors (50.2%), serological DR and DQ typing was confirmed using molecular biology techniques; HLA-DRB1, HLA-B3, HLA-B4, HLA-B5, and HLA-DQB were biologically typed using TaqI RFLP,9 or the locus amplification method specification of the second exon of class II and hybridization with a PCR-oligonucleotides specific sequence.10

Statistical analysis

The relative risk (RR) was calculated comparing the ADA-positive and ADA-negative sample populations by using Microsoft Excel for Windows, 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA). Then, by evaluating a 95% acceptable confidence, a confidence interval was calculated by deducting it using the standard error methodology.

Results

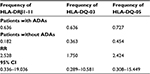

After 6 months of treatment, we observed ADAs in 2/26 patients treated with IFX (7.69%), 5/83 patients treated with ADA (6.02%), 5/88 patients treated with ETA (5.68%), 4/32 patients treated with CERT (12.5%), and 1/19 patients treated with GOL (5.26%). After inhibition testing, the frequency of ADAs was 2/26 patients treated with IFX (7.69%); 4/83 treated with ADA (4.81%); 0/88 treated with ETA (0%); 4/32 treated with CERT (12.5%); and 1/19 treated with GOL (5.26%) (Table 2). The frequency of HLA alleles in the 11 ADA-positive examined patients was HLA-DRβ-11 0.636, HLA-DQ-03 0.636, and HLA-DQ-05 0.727; the frequency of HLA alleles in the ADA-negative population was HLA-DRβ-11 0.182, HLA-DQ-03 0.363, and HLA-DQ-05 0.454. The estimated RRs between the ADA-positive patients and the ADA-negative patients were 2.528 (95% CI 0.336–19.036), HLA-DQ-03 1.750 (95% CI 0.289–10.581), and HLA-DQ-05 2.424 (95% CI 0.308–15.449) (Table 3).

| Table 3 HLA frequency in rheumatic patients with and without ADAs Abbreviations: ADAs, antidrug antibodies; RR, relative risk. |

Discussion

This study shows an association between HLA and genetic factors associated with the occurrence of ADAs in patients with rheumatic diseases. An inadequate response to anti-TNF drugs in RA patients may be due to the development of ADAs.2 Previous studies found a correlation between the IL10 genotype and the production of ADA ADAs.4 IL-10, a cytokine that plays a key role in antibody development, is associated with the production of antibodies that inhibit recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) in patients with hemophilia11 and autoantibodies against nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in patients with myasthenia gravis (MG).12

Using high-resolution HLA class I and II typing, we identified three HLA class II alleles associated with the development of antibodies: HLA-DRβ-11 (RR 2.528), HLA-DQ-03 (RR 1.750), and HLA-DQ-05 (RR 2.424) in comparison with the ADA-negative population. An association between HLA and the development of ADAs has also been found in other diseases, with HLA-DRβ1* 04:01, HLA-DRβ1*04:08, and HLA-DRβ1 *16:01 being identified as genetic markers of an increased risk of developing anti-interferon beta (IFN-β) antibodies.13 Three studies have shown an association between HLA and ADAs against IFN-β.13–15 Smoking is a risk factor for the development of multiple sclerosis (MS), and the risk is greater if smoking is combined with well-known HLA associations. It is also a risk factor for the development of ADAs in IFN-β- and natalizumab-treated MS patients,16,17 as well as for the development of RA by means of a mechanism of citrullination.

As in the case of other drugs, the development of ADAs against TNF-α-blocking monoclonal antibodies depends on many factors: environmental and genetic factors, disease pathophysiology-related variations, and drug preparation and administration. ADAs appear soon after the start of the treatment,18 and their frequency varies considerably depending on the drug and assay method used.19,20 To the best of our knowledge, there are limited published data concerning the T cell epitopes involved in immune responses to anti-TNF agents, although a number of research groups are beginning to investigate this field. One study has identified a T cell epitope associated with the IGHG1 G1m1 allotype that can induce T cell proliferation in healthy subjects with a different allotype.21 As ADA contains this T cell epitope, patients with the IGHG1 G1m1 allotype may have a reduced propensity to produce ADA ADAs, but this view is contradicted by the results of a study showing increased ADA-induced immunogenicity in patients with this allotype.22

Some anti-TNF agents may include multivalent antigens that can induce T cell-independent ADA formation as a result of extensive B cell receptor cross-linking (which causes B cell activation regardless of T cell help).23 A number of studies have shown that concomitant immunosuppression reduces the induction of ADAs, which suggests that this treatment may be sufficient to ensure a good treatment response or at least delay the development of ADAs.24,25 As for FVIII treatment, there have been attempts to induce immunological tolerance through high doses of IFX, which is believed to exhaust the immune response.26 The ADA frequencies observed in our study are similar to those reported in the literature.27 The different frequency of the development of ADAs depends on the method used (ELISA, radioimmunoassay [RIA], antigen-binding test, pH-shift anti-idiotype) the underlying disease (RA, PsA, inflammatory bowel disease, spondyloarthritis) and by the concomitant use of immunosuppressive treatment such as methotrexate.28

It is known that the large individual variations in the treatment responses of patients with RA are influenced by factors such as gender, body mass index, and the degree of inflammation,29 but this is the first study to show an association between HLA and genetic factors associated with the occurrence of ADAs in patients with rheumatic diseases. An important limitation of our study is that HLA-DRB1 and HLA-DQB1 association at the four-digit level is not presented. The number of samples is too small to draw any definite conclusion, and further comparative studies are now required to investigate rheumatic patients who do not develop ADAs vs healthy subjects, and non-ADA patients and healthy subjects.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):601–608. | ||

Pascual-Salcedo D, Plasencia C, Ramiro S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the efficacy of long-term treatment with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(8):1445–1452. | ||

Atzeni F, Talotta R, Salaffi F, et al. Immunogenicity and autoimmunity during anti- TNF therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(7):703–708. | ||

Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Anti-adalimumab antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis patients are associated with interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(8):2541–2542. | ||

Carpenter J, Cherney B, Lubinecki A, et al. Meeting report on protein particles and immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: filling in the gaps in risk evaluation and mitigation. Biologicals. 2010;38(5):602–611. | ||

Chirino AJ, Mire-Sluis A. Characterizing biological products and assessing comparability following manufacturing changes. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(11):1383–1391. | ||

Hermeling S, Schellekens H, Maas C, Gebbink MF, Crommelin DJ, Jiskoot W. Antibody response to aggregated human interferon α2b in wild-type and transgenic immune tolerant mice depends on type and level of aggregation. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95(5):1084–1096. | ||

Terasaki PI, McClelland JD. Microdroplet assay for human serum cytotoxins. Nature. 1964;204:998. | ||

Amoroso A, Mazzola G, Berrino M, et al. HLA class II gene frequencies in Italy. Gene Geogr. 1991;5(1–2):75–86. | ||

Kimura A, Dong RP, Harada H, Sasazuki T. DNA typing of class II genes in B-lymphoblastoid cells lines homozygous for HLA. Tissue Antigens. 1992;40:5. | ||

Astermark J, Oldenburg J, Pavlova A, Berntorp E, Lefvert AK; The MIBS Study Group. Polymorphisms in the IL10 but not in the IL1and IL4 genes are associated with inhibitor development in patients with hemophilia A. Blood. 2006;107(8):3167–3172. | ||

Huang DR, Zhou YH, Xia SQ, Liu L, Pirskanen R, Lefvert AK. Markers in the promoter region of interleukin-10 (IL-10) gene in myasthenia gravis: implications of diverse effects of IL-10 in the pathogenesis of the disease. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;94(1–2):82–87. | ||

Buck D, Cepok S, Hoffmann S, et al. Influence of the HLA-DRB1 genotype on antibody development to interferon beta in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(4):480–487. | ||

Link J, Lundkvist Ryner M, Fink K, et al. Human leukocyte antigen genes and interferon beta preparations influence risk of developing neutralizing anti-drug antibodies in multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90479. | ||

Hoffmann S, Cepok S, Grummel V, et al. HLA-DRB1*0401 and HLA-DRB1*0408 are strongly associated with the development of antibodies against interferon-beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(2):219–227. | ||

Nunez C, Cenit MC, Alvarez-Lafuente R, et al. HLA alleles as biomarkers of high-titre neutralising antibodies to interferon-beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. J Med Genet. 2014;51(6):395–400. | ||

Hedstrom A, Alfredsson L, Lundkvist RM, Fogdell-Hahn A, Hillert J, Olsson T. Smokers run increased risk of developing anti-natalizumab antibodies. Mult Scler. 2013;20(8):1081–1085. | ||

Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Development of antidrug antibodies against adalimumab and association with disease activity and treatment failure during long-term follow-up. JAMA. 2011;305(14):1460–1468. | ||

van Schouwenburg PA, Rispens T, Wolbink GJ. Immunogenicity of anti-TNF biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(3):164–172. | ||

Wolbink GJ, Vis M, Lems W, et al. Development of antiinfliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):711–715. | ||

Stickler M, Reddy A, Xiong JM, Hinton PR, DuBridge R, Harding FA. The human G1m1 allotype associates with CD4+ T-cell responsiveness to a highly conserved IgG1 constant region peptide and confers an asparaginyl endopeptidase cleavage site. Genes Immun. 2011;12(3):213–221. | ||

Bartelds GM, Tak PP, Aarden L, et al. Surprising negative association between IgG1 allotype disparity and anti-adalimumab formation: a cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(6):R221. | ||

Schellekens H. Immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(7):1257–1259. | ||

Bendtzen K, Geborek P, Svenson M, Larsson L, Kapetanovic MC, Saxne T. Individualized monitoring of drug bioavailability and immunogenicity in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with the tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3782–3789. | ||

Ternant D, Ducourau E, Perdriger A, et al. Relationship between inflammation and infliximab pharmacokinetics in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(1):118–128. | ||

Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1552–1563. | ||

Spinelli FR, Valesini G. Immunogenicity of anti-tumour necrosis factor drugs in rheumatic diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013;31(6):954–963. | ||

Thomas SS, Borazan N, Barroso N, et al. Comparative immunogenicity of TNF inhibitors: impact on clinical efficacy and tolerability in the management of autoimmune diseases. a systematic review and meta-analysis. BioDrugs. 2015;29(4):241–258. | ||

Ternant D, Ducourau E, Fuzibet P, et al. Pharmacokinetics and concentration-effect relationship of adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(2):286–297. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.