Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 8

Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: current perspectives

Authors Yao K, Sisco M, Bedrosian I

Received 29 October 2015

Accepted for publication 28 February 2016

Published 22 June 2016 Volume 2016:8 Pages 213—223

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S82816

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Katharine Yao,1 Mark Sisco,2 Isabelle Bedrosian3

1Division of Surgical Oncology, Department of Surgery, 2Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, IL, 3Department of Surgery, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract: There has been an increasing trend in the use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) in the United States among women diagnosed with unilateral breast cancer, particularly young women. Approximately one-third of women ,40 years old are undergoing CPM in the US. Most studies have shown that the CPM trend is mainly patient-driven, which reflects a changing environment for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. The most common reason that women choose CPM is based on misperceptions about CPM’s effect on survival and overestimation of their contralateral breast cancer (CBC) risk. No prospective studies have shown survival benefit to CPM, and the CBC rate for most women is low at 10 years. Fear of recurrence is also a big driver of CPM decisions. Nonetheless, studies have shown that women are mostly satisfied with undergoing CPM, but complications and subsequent surgeries with reconstruction have been associated with dissatisfaction with CPM. Studies on surgeon’s perspectives on CPM are sparse but show that the most common reasons surgeons discuss CPM with patients is because of a suspicious family history or for a patient who is a confirmed BRCA mutation carrier. Studies on the cost–effectiveness of CPM have been conflicting and are highly dependent on patient’s quality of life after CPM. Most recent guidelines for CPM are contradictory. Future areas of research include the development of interventions to better inform patients about CPM, modification of the guidelines to form a more consistent statement, longer term studies on CBC risk and CPM’s effect on survival, and prospective studies that track the psychosocial effects of CPM on body image and sexuality.

Keywords: contralateral breast cancer, surgical decision making

Introduction

In 1991, the National Institutes of Health published a consensus statement1 that stated that breast conservation surgery (BCS) was “preferable” for early-stage breast cancer because it provided equivalent survival to mastectomy.2–8 Shortly after this statement, the rate of BCS increased.9 However, over the past decade, we have witnessed a shift back toward mastectomies, particularly contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM). This trend has surfaced despite the absence of randomized trials for CPM and any official consensus statement endorsing CPM. Most studies show that the CPM trend is patient driven, reflecting a changing environment for newly diagnosed patients, where patients have increased exposure to breast cancer through the media and patient advocacy groups and patient’s access to many different sources of information has increased. Patients are taking more proactive roles in treatment decisions and seeking more opinions, not only from doctors but also from friends, family, and other breast cancer survivors.10 Moreover, improved access to reconstructive surgery,11 improved reconstructive techniques, and better mastectomy techniques, like nipple-sparing mastectomy, have also influenced patient’s decision making. Additionally, physicians are now ordering more preoperative diagnostic tests and consultations to provide more information for patients to make a surgical decision, and these additional efforts have been associated with more mastectomy procedures.12,13 All of these factors have drastically changed the surgical decision-making process from where it was more than a decade ago.

In this article, we review trends in CPM over the past 10–15 years and factors associated with these trends. We also examine recent literature on CPM and survival and contralateral breast cancer (CBC) risk. Next, we discuss current perspectives on CPM from the patient, physician, and “system” points of view. We explore patient motivations for choosing CPM, patient satisfaction and quality of life (QOL) with CPM, and knowledge about how CPM affects outcomes. Surgeons’ perspectives on CPM, its utility, and their knowledge level regarding CPM are presented. We also examine the impact of CPM on health care costs and delivery. Finally, we discuss how to counsel patients on CPM, the “pros and cons” of CPM, and areas where future research is needed for the field.

Trends in CPM

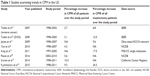

In 2007 and 2009, two Surveillance Epidemiology End Results (SEER) studies reported that the rate of CPM had increased 148% and 150% among all patients for noninvasive and invasive cancer, respectively.14,15 When patients undergoing mastectomy were examined, there was a 188% and 162% increase, respectively. These two studies were the first in a string of studies examining the increasing CPM rate across the US (Table 1).11,14–20 In 2010, a report from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) showed an increase in CPM from 0.4% in 1998 to 4.7% in 2007.16 A 2011 study from Memorial Sloan Kettering reported that 6.7% mastectomy patients underwent CPM in 1997, which increased to 24.2% in 2005.11 These studies and others show increasing CPM across all stages, different areas of the country, all ages, insurance types, and facility types.11,14–17,21 Certain characteristics were similar across all studies. CPM rates are highest among Caucasians, and patients with higher socioeconomic status, with private insurance, and treated at high-volume centers.14–16 Even a recent study of males showed an increase in CPM, and this trend was also associated with white race, young age, and private insurance.22 Race and socioeconomic status also play a role in CPM; CPM is twice as common in Caucasians than other races23 despite adjusting for socioeconomic factors. Patient age has consistently been shown to be the strongest factor associated with the increasing CPM rate. An NCDB study showed that CPM rates in 2011 were 9.7% among all age groups, but this percentage increased to 26% among those younger than 45 years.20 In a study of the California Cancer Registry,19 >30% of women <40 years old underwent CPM in 2011. However, this increasing trend for CPM has not been as evident in other countries. An article focused on Europe24 did not show an increase in European CPM rates; however, one article reported that CPM rates in Britain have been increasing.25 These findings underscore how cultural perceptions about CPM can have a profound effect on treatment preferences. Indeed, a study of BRCA carriers, the highest risk cohort for CBC, showed wide variability in bilateral prophylactic mastectomy for prevention of cancer; 2.7% of BRCA carriers in Poland had a bilateral prophylactic mastectomy compared to 36% in the US.26

There are many external factors that could influence a woman’s decision to undergo CPM. Newly diagnosed patients more often undergo multiple preoperative diagnostic tests. A study from the Mayo Clinic12 showed that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) use increased from 10% in 2003 to 23% in 2006 and MRI was an independent mastectomy predictor. Likewise, another study showed MRI use increased from 4.1% in 1998 to 23.7% in 2005 and women who underwent MRI were twice as likely to undergo CPM.27 Similarly, genetic testing has become more prevalent and has been shown to be associated with increasing CPM rates.28,29 One study showed that despite negative testing, 58% of patients underwent CPM.28 Access to breast reconstructive surgery has also increased29 and been shown to influence CPM rates. A recent SEER study30 reported that the proportion of CPM patients who underwent reconstruction increased from 19% in 2000 to 46% in 2010. Reconstructive surgery is an independent predictor of CPM,11,21,30 with one study showing that reconstruction patients had over two times the risk of CPM.30 Finally, patients have access to more varied sources of information than a decade ago. Over 50% of patients use the internet regularly before seeing their doctor.31 Patients may pursue other sources of information besides their physician for advice. A study from Canada reported that the most influential information source in choosing CPM was personal experience with family or friends who have “lived with cancer”.10 It is clear that the decision-making process for CPM is very complex and is influenced by multiple different factors. Some factors play a larger role than others, and patients will weigh certain factors more than others when making their decision. Physicians will need to learn how to navigate patients through this ever-changing decision-making process.

CPM’s effects on patient outcomes: survival and CBC risk

Multiple single- and multi-institution studies published over the past 10–15 years in the US have examined CPM’s effect on overall and disease-free survival, but results are conflicting and complicated by the fact that none are prospective randomized studies (Table 2).19,32–39 It is unlikely that a randomized trial of CPM versus unilateral mastectomy (UM) or lumpectomy will be done in the near future. A Cochrane analysis published in 2009 concluded that CPM did not provide a survival benefit.40 Four single-32,35,39,41 and three multi-institution33,34,38 studies demonstrated a disease-free survival benefit for CPM, while two single-35,42 and three multi-institution33,37,38 studies showed an overall survival benefit. Since these studies are retrospective, selection bias could account for the reported survival benefit. An NCDB study showed that the unadjusted hazard ratio for death was 0.55 for CPM, but when adjusting for patient, tumor, and facility factors, the hazard ratio increased to 0.88, which translated to an absolute survival benefit of only 2%.37 A recent SEER study38 showed that when CBC cases were removed from the analysis, it had little impact on CPM’s survival benefit, which shows that CBC has little to do with survival. Patients who undergo CPM may be more healthy, more compliant with their treatment regimens, and have access to more advanced treatments than patients who do not undergo CPM.

CPM can only provide a survival benefit if it is preventing a more lethal cancer than the primary tumor. Although many studies have shown that CBCs tend to have more favorable tumor characteristics, studies have shown that patients who develop CBCs in a short interval from their primary cancer have worse survival than those who develop a CBC at a longer interval.43–47 Patients who had worse survival with CBC were young patients, patients with large tumors, and node-positive patients.44–46 It is not clear if the reported worse survival is because these CBCs represent aggressive biology of the primary tumor, distant metastatic disease, or perhaps just older, inferior systemic treatments. Studies have also examined how CPM affects survival in those patient cohorts who are at higher risk for CBC. BRCA mutation carriers derive survival benefit from CPM,48 which is understandable given the high CBC risk for BRCA carriers.49–51 CBC risk for other gene mutation carriers who have breast cancer is not well studied with the exception of (CHEK2) 1100delC mutation carriers.52,53 A SEER study showed that women <50 years old with estrogen receptor (ER)-negative tumors had better breast cancer specific survival then older patients with ER positive tumors presumably because some of these patients could have been BRCA mutation carriers.34 However, other studies have not shown survival benefit for ER-negative patients.54,55 Patients with family history of breast cancer have a higher CBC risk, but a recent meta-analysis of CPM survival studies showed no survival advantage to those with suspicious family history.56 Further study is needed to determine which patients are really at high risk of CBC and whether these patients would really benefit from CPM at the time of their primary tumor.

CPM’s effect on CBC risk is less controversial. CPM will reduce the risk of CBC effectively, but a small risk of cancer still exists on the prophylactic side.57 Many women choose CPM to reduce their risk of a contralateral cancer,58 but they often overestimate their CBC risk.59 The CBC risk for average risk women is low. Population-based studies and clinical trials (Table 3)33,60–68 that track CBC rates have shown that the CBC risk at 10 years is ≤5%. An Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group overview quotes 0.4% and 0.5% annual risk of CBC for ER-positive and -negative patients, respectively.69 This translates into an ~5% risk at 5 years and 10% at 10 years. However, the overview encompasses older clinical trials and, in fact, a SEER study from 2009 showed that CBC rates have been dropping 3%/year, likely secondary to the use of hormonal therapy.63 CBC rates for higher risk subgroups have been studied. A Women’s Environmental Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology66 study showed that a 30-year-old women with a first-degree relative with breast cancer has a CBC risk at 10 years of 14.7%, but this risk decreases to 6.7% for women in their fifties. An SEER study63 reported that the 10-year CBC risk for a woman 25–29 years old with an ER-negative tumor is 1.26 per 100/year compared to 0.45 per 100/year for an ER-positive tumor. In contrast, the 10-year risk for a 50-year-old women with an ER-negative tumor is 0.45 per 100/year compared to 0.26 per 100/year for an ER-positive tumor. These data demonstrate a differential risk for CBC according to patient age, ER status, and family history. Future studies are needed to determine how CBC risk varies according to these risk factors, but this will be challenging, given that many national databases do not contain CBC information and the long follow-up needed to study CBC risk.

Patient perspectives on CPM

Patient motivations for choosing CPM

Changes in the external environment have no doubt influenced patient’s decisions to pursue CPM. In fact, studies have shown that patients most often bring up CPM rather than their doctor.10,70 The most common reasons to choose CPM revolve around survival and risk of a second breast cancer. In a multi-institution study of 123 young women, “desire to lower the chance of getting cancer in the other breast” was ranked as the most important reason women chose CPM, with 98% of women stating it was extremely or very important in their decision to undergo CPM.58 The third most common reason was to “improve survival”, with 94% stating it was extremely or very important; desire to prevent cancer from spreading to other parts of the body was the fourth most common reason, with 85% stating it was extremely or very important. In a single-institution study of 191 CPM patients, “fear of recurrence” was the top reason influencing women to elect CPM.71 Another retrospective survey study showed that the most common reason women underwent CPM was “worry about getting another breast cancer”.72 In a study that surveyed women who were felt to be BCS candidates but chose mastectomy, “reduced recurrence” and “improved survival” were the two top reasons to undergo a mastectomy.73 In a Canadian study of 29 mastectomy patients who underwent semi-structured interviews, “taking control of the cancer” was the “dominant theme”, and most patients felt that removing both breasts would give them a better survival rate.10 Interestingly, all 29 of these patients recalled their surgeon telling them that survival was equivalent between the surgical procedures. Clearly, concern about cancer outcome dominates motivation to choose CPM. Many patients have high levels of preoperative “cancer worry” and fear of recurrence.58,74 Patients describe being in a state of “shock and panic” after diagnosis.10 Cancer worry has been associated with CPM interest and the performance of CPM.74 Anxiety and worry are also likely a cause of cognitive dissonance; women choosing CPM to improve survival often correctly answer questions regarding the lack of CPM’s association with recurrence and survival.58 Less common reasons to choose CPM include avoiding screening mammograms and biopsies that may follow and family history.58,71,72 In the study of young women who had undergone CPM, “worry that screening would not find cancer in the other breast” was extremely or very important to 49% of participants, and family history was extremely or very important to 37% of participants. Cosmesis concerns also drive decision making. Symmetry concerns were extremely or very important to 57% of participants in the young women study,58 and 59% of women in another study stated that reconstructive surgery availability influenced their decision.71 Indeed, a single-institution study reported that immediate breast reconstruction was performed in 87% of patients undergoing CPM compared to 51% of patients undergoing UM.11 Friends, family, and spouses also influence patients,10,71 particularly if one of these individuals has been through breast cancer or other cancers.

Although more women are undergoing CPM than 10 years ago, many more consider CPM as a surgical choice in the preoperative setting. An SEER study showed that roughly 19% of women considered CPM, but “worry about cancer recurrence” was significantly higher among those who actually underwent CPM.29 A prospective study of 117 patients found that 50% of women were moderately or strongly interested in CPM prior to surgery. This preference for CPM was associated with higher levels of cancer worry, young age, and low knowledge about breast cancer74 but after adjusting for patient factors, preference for CPM was only associated with high cancer worry. These studies highlight the important role that anxiety plays in decision making.

Patient satisfaction and QOL with CPM

Most studies have shown that women are generally satisfied with their decision to undergo CPM. Satisfaction rates with CPM range from 80% to 97%, and the same percentage would have chosen CPM again if given the choice.42,58,71,72 In one study, patients who had undergone UM stated they would not have undergone this procedure if they could choose again; 67% stated that they would have preferred in retrospect to undergo CPM.72 A large retrospective study was conducted on patients with breast cancer history who underwent CPM between 1966 and 1993 and asked patients about satisfaction with the procedure, body appearance, sexual relationships, and overall emotional stability.75 With 10 years of median follow-up, 83% reported they were satisfied with their surgery. However, some women do report dissatisfaction with CPM related to reconstructive procedures or unexpected subsequent procedures; 33% reported that CPM had a negative effect on body appearance.75 Decreased satisfaction with CPM was associated with reconstruction type, complications, mastectomy type, and overall stress. A report with longer follow-up on the same cohort of patients showed that 92% of patients were satisfied with their decision to undergo CPM but that body appearance, feelings of femininity, and sexual relationships were negatively affected in 23%–31% of patients.76 A recent report also showed that nearly 40% of those who had reconstruction had at least one unplanned reoperation.42 Reoperation was associated with lower satisfaction with CPM, lower likelihood of undergoing reconstruction again, and lower likelihood of choosing CPM. In a more recent study on young women, ~30% reported that surgical outcomes were worse than expected, especially regarding chest wall numbness and the need for multiple procedures.58 Interestingly, in 1999, Montgomery et al77 reported that only 6% women undergoing CPM regretted their decision. Forty percent cited poor cosmetic results as to why they regretted choosing CPM, and 22% cited lack of education regarding alternatives or CPM efficacy.77 A more recent study utilizing the Breast Q assessed satisfaction with breast appearance and outcomes between CPM and UM patients with implant reconstruction.78 The study reported that CPM was an independent predictor of satisfaction with the breasts but not breast reconstruction outcome satisfaction. One prospective study conducted in Sweden showed that QOL, anxiety, depression, and sexuality were no different before and after CPM but that ~50% of women reported at least one body image problem postoperatively.79

Retrospective studies have shown that QOL is similar between CPM and non-CPM patients. One retrospective study assessed 519 women from six health care delivery systems who had undergone CPM between 1979 and 1999. This study showed no difference in QOL between patients with and without CPM.80 Less contentment with QOL was associated with poor health perception overall, not the decision to undergo CPM.80 A similar study in patients at increased risk for breast cancer who had undergone bilateral prophylactic mastectomy81 showed the same results; bilateral prophylactic mastectomy was not associated with better psychosocial outcome.

Patient knowledge about CPM

Patients often lack knowledge about their CBC risk and how CPM affects their outcomes. Studies have shown that patients’ lack of knowledge regarding CPM has been associated with preoperative CPM interest.74 Women often choose CPM to decrease CBC risk, but women often overestimate their CBC risk.58,59 In a preoperative survey study, patients estimated CBC risk at 31.4% over a 10-year period.59 Interestingly, the perceived CBC risk was not different between CPM, UM, and BCS patients.59 Patients often have the misperception that CPM will eliminate risk of any type of breast cancer recurrence.58 Seventy-three percent of women in one study stated that there was no difference in survival between surgical options, but of the 27% who felt there was a difference, ~60% felt that BM patients would live longest.58 Qualitative interviews with breast cancer patients revealed that women often felt that CPM would “insure a better survival”.10 These misperceptions are the primary drivers behind CPM.

Surgeon perspectives about CPM

There are little data in the literature on physician’s CPM knowledge and perceptions. One Australian study70 reported that surgeon age and sex were not related to CPM rates, contrasting another study that showed higher CPM rates among female surgeons.82 Most physicians report that patient motivations drive the decision to undergo CPM, with surgeons discussing it with patients only 5%–20% of the time.70 This is consistent with the patient perspective; in Rosenberg’s study, 36% of noncarriers discussed reasons for CPM, and only 15% said that their physician discussed the downsides of CPM. More importantly, only 33% of patients stated that their physician talked about CBC.58 In the Australian study, surgeons stated that “fear and anxiety” was the most common reason women requested a CPM.70 When asked when they would recommend a CPM, surgeons stated BRCA carrier status and strong family history were the most common reasons with patient initiative as the third most common.

Similar to patients, some physicians lack knowledge about CPM.83 A survey study of the American Society of Breast Surgeons showed that ~40% of surgeons had “low knowledge” about CPM, particularly about CBC risk in certain patient subgroups. Understanding physician’s knowledge base and perceptions is crucial to understanding how physicians inform their patients and what influence they have on a patient’s decision to undergo CPM. Indeed, Rosenberg’s study showed that physicians were the most important source of information and have an enormous influence on patient decision making.58

In a subsequent study of the American Society of Breast Surgeons survey, we have shown that 57% of surgeons have experienced “discomfort” in performing CPM sometime in their career (unpublished data). Future studies of this dataset will enable us to learn reasons why surgeons are uncomfortable performing CPM and what interventions, if any, would surgeons like to increase their comfort level.

Impact of CPM on the health care system

CPM’s effect on operative complications, delays in treatment, and cost

Although CPM is an individual choice, its costs and impact on the “system” can be substantial, since there are risks associated with CPM. CPM has been shown to delay adjuvant treatments and delay time to surgical resection.84 These delays could be significant given that some studies have shown adverse outcomes in certain patient cohorts.85 Delays could also impact certain quality measures such as timeliness of care and time to the operating room. Several studies have shown that the risk of operative complications is higher with CPM, and in several studies, this risk was double that of UM.86–88 In one single-institution study of 600 patients, 40% of CPM patients had complications compared to 28% of UM patients. Patients who had CPM were 1.5 times more likely to have any complication than UM patients when adjusting for multiple factors and 2.7 times more likely to have a major complication. The most common minor complication was infection requiring antibiotics, and the most common major complication was implant or tissue expander removal.87 Similar to another single-institution study, the complications occurred approximately equally between the prophylactic and index breast.86,87 Likewise, the risk of complications in another retrospective review performed at two institutions showed that each breast incurred the same percentage of complications, roughly 20%, and the risk of complications in both breasts was 11%.86 In a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program study, the overall 30-day complication rate and wound infection rate were twice as high in BM patients as UM patients for those not undergoing reconstruction.88 In another National Surgical Quality Improvement Program study, reoperation rates were higher in the reconstructed BM group compared to the reconstructed UM group, and wound disruption was higher in BM patients undergoing autologous reconstruction.89

Several studies have examined cost and cost-effectiveness of CPM utilizing a Markov model or cost estimates. A decision tree analysis of women <50 years old with unilateral breast cancer showed that CPM was cost saving to prevent CBC but also resulted in loss of quality-adjusted life years because of increased complications, costs of reconstruction, and time off work. The authors concluded that the data were insufficient to consider CPM as cost effective.90 Another study91 utilized a Markov model to examine cost- effectiveness of CPM. CPM was cost effective if the “utility weights” for CPM were greater than surveillance; however, if this assumption was not true, then CPM may not have been cost effective. A major weakness of this study was the fact that it did not include costs related to reconstruction or operative complications nor did it consider ER status of the tumors, which would impact CBC risk and thus potential benefit of CPM as a risk-reducing intervention. Patients should be made aware of these downsides to CPM and how these issues could potentially impact their overall outcome.

Counseling patients on CPM

Counseling patients on CPM is complex, given the multiple factors that influence a woman’s decision to undergo CPM. It is important to insure that patients are making decisions of high quality when it comes to CPM; decisions should be informed, shared between physician and patient, and reflective of patient’s values and concerns. Patients should be informed of the low CBC risk for most patients, how CPM affects survival, the risks associated with CPM and CPM’s effect on sexuality cosmesis and sensation. A discussion of both the “pros” and “cons” of CPM as outlined in Table 4 will facilitate shared decision making between the patient and physician. Physicians and patients tend to focus on the benefits of CPM but not always the “cons”.92 Surgeons should ask patients questions that would elicit their values and preferences such as their feelings about radiation therapy, recovery time, importance of keeping the breast, cosmesis and their treatment preference. Good candidates for CPM would be BRCA mutation carriers because of their high risk of CBC and possibly CHEK2 1100delC.52,53 Other good candidates would be patients with family histories that are highly suspicious for a hereditary component, and those who have undergone mantle cell radiation. Patients who should be discouraged from undergoing CPM are those with a high risk of operative complications (obese, heavy smoker, many comorbidities), those with a high risk of distant recurrent disease (locally advanced or inflammatory cancers, clinical T4 or N3 tumors, and certain molecular subtypes of cancers), those with stage IV disease, and those who feel that CPM will replace systemic therapy when systemic therapy is indicated.

| Table 4 Pros and cons of CPM |

Conclusion and future directions

Although patients have been undergoing CPM for decades, the recent increase in CPM trends have concerned clinicians that patients are making uninformed and even harmful decisions. These concerns have led to numerous studies investigating all aspects of CPM, including survival, decision making, QOL, cost-effectiveness, and satisfaction. Nonetheless, there still remain significant gaps in the field that warrant future investigation. First, development of a CPM decision intervention is needed. Previous tools that have examined BM have focused primarily on BRCA gene carriers.93 Teaching materials or a decision aid that can clearly outline CBC risks, local recurrence risks, and the impact of CPM on survival is needed. These could address patients’ knowledge gaps regarding CPM and values and goals for treatment. By better informing patients and aligning their decisions with their goals, such tools should facilitate more shared decision making between patient and physician. There have already been three randomized trials over a decade ago that examined various types of decision aids for decision making between BCS and mastectomy. These studies all showed that decision aids increase patient knowledge and satisfaction.94–96 Yet, few surgeons utilize decision aids, perhaps because none of these trials were conducted in the United States. Any decision intervention study will need to be closely coupled with measure to increase physician adoption, particularly breast surgeons. Second, some guidance from national surgical societies or national guidelines on CPM or consensus guidelines for CPM would be helpful for physicians and patients. The most recent guidelines are contradictory. A position statement from the Society of Surgical Oncology in 2007 stated that CPM could be considered for those with a high risk of CBC, for those where surveillance of the contralateral breast will be difficult, and for symmetry purposes.97 However, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2015 guidelines state that CPM is discouraged.98 More updated, consistent statements would be helpful. Third, stronger studies on CPM’s effect on outcomes are needed. Studies that more accurately assess CBC risk according to patient factors such as family history, ER status, and patient age are needed. Survival studies that focus on groups of patients who have higher risks for CBC with longer follow-up may demonstrate a survival benefit for CPM. These studies would allow physicians to more accurately counsel patients on their CBC risk and how CPM affects their survival outcomes. Fourth, prospective tracking of psychological aspects of CPM and how CPM affects body image, self-assurance, and sexuality is needed. Although these topics have been addressed in older studies,75,99 what value women place on their body image and their breast appearance has likely changed since these publications, and likely plays a large role in decision making regarding CPM.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

NIH consensus conference. Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265(3):391–395. | ||

Fisher B, Bauer M, Margolese R, et al. Five-year results of a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy and segmental mastectomy with or without radiation in the treatment of breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1985;312(11):665–673. | ||

Blichert-Toft M, Rose C, Andersen JA, et al. Danish randomized trial comparing breast conservation therapy with mastectomy: six years of life-table analysis. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 1992;(11):19–25. | ||

Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(16):1227–1232. | ||

Sarrazin D, Le MG, Arriagada R, et al. Ten-year results of a randomized trial comparing a conservative treatment to mastectomy in early breast cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology: Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 1989;14(3):177–184. | ||

van Dongen JA, Bartelink H, Fentiman IS, et al. Randomized clinical trial to assess the value of breast-conserving therapy in stage I and II breast cancer, EORTC 10801 trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 1992;(11):15–18. | ||

Effects of radiotherapy and surgery in early breast cancer. An overview of the randomized trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333(22):1444–1455. | ||

Morris AD, Morris RD, Wilson JF, et al. Breast-conserving therapy vs mastectomy in early-stage breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 10-year survival. The Cancer Journal from Scientific American. 1997;3(1):6–12. | ||

Lazovich D, Solomon CC, Thomas DB, Moe RE, White E. Breast conservation therapy in the United States following the 1990 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on the treatment of patients with early stage invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86(4):628–637. | ||

Covelli AM, Baxter NN, Fitch MI, McCready DR, Wright FC. ‘Taking control of cancer’: understanding women’s choice for mastectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(2):383–391. | ||

King TA, Sakr R, Patil S, et al. Clinical management factors contribute to the decision for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(16):2158–2164. | ||

Katipamula R, Degnim AC, Hoskin T, et al. Trends in mastectomy rates at the Mayo Clinic Rochester: effect of surgical year and preoperative magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(25):4082–4088. | ||

Miller BT, Abbott AM, Tuttle TM. The influence of preoperative MRI on breast cancer treatment. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2012;19(2):536–540. | ||

Tuttle TM, Habermann EB, Grund EH, Morris TJ, Virnig BA. Increasing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for breast cancer patients: a trend toward more aggressive surgical treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(33):5203–5209. | ||

Tuttle TM, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, et al. Increasing rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(9):1362–1367. | ||

Yao K, Stewart AK, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral cancer: a report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2007. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2010;17(10):2554–2562. | ||

Jones NB, Wilson J, Kotur L, Stephens J, Farrar WB, Agnese DM. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer: an increasing trend at a single institution. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009;16(10):2691–2696. | ||

Kummerow KL, Du L, Penson DF, Shyr Y, Hooks MA. Nationwide trends in mastectomy for early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(1):9–16. | ||

Kurian AW, Lichtensztajn DY, Keegan TH, Nelson DO, Clarke CA, Gomez SL. Use of and mortality after bilateral mastectomy compared with other surgical treatments for breast cancer in California, 1998–2011. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(9):902–914. | ||

Pesce CE, Liederbach E, Czechura T, Winchester DJ, Yao K. Changing surgical trends in young patients with early stage breast cancer, 2003 to 2010: a report from the National Cancer Data Base. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2014;219(1):19–28. | ||

Yi M, Hunt KK, Arun BK, et al. Factors affecting the decision of breast cancer patients to undergo contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, PA). 2010;3(8):1026–1034. | ||

Jemal A, Lin CC, DeSantis C, Sineshaw H, Freedman RA. Temporal trends in and factors associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among US men with breast cancer. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150(12):1–3. | ||

Grimmer L, Liederbach E, Velasco J, Pesce C, Wang CH, Yao K. Variation in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy rates according to racial groups in young women with breast cancer, 1998 to 2011: a report from the National Cancer Data Base. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2015;221(1):187–196. | ||

Guth U, Myrick ME, Viehl CT, Weber WP, Lardi AM, Schmid SM. Increasing rates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy – a trend made in USA? European Journal of Surgical Oncology: The Journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2012;38(4):296–301. | ||

Neuburger J, Macneill F, Jeevan R, van der Meulen JH, Cromwell DA. Trends in the use of bilateral mastectomy in England from 2002 to 2011: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003179. | ||

Metcalfe KA, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Lubinski J, et al. International variation in rates of uptake of preventive options in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. International Journal of Cancer. Journal International du Cancer. 2008;122(9):2017–2022. | ||

Sorbero ME, Dick AW, Beckjord EB, Ahrendt G. Diagnostic breast magnetic resonance imaging and contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009;16(6):1597–1605. | ||

Wang F, Amara D, Peled AW, et al. Negative genetic testing does not deter contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in younger patients with greater family histories of breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(10):3338–3345. | ||

Hawley ST Jr, Morrow M, Katz SJ. Correlates of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in a population based sample. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:6010. | ||

Agarwal S, Kidwell KM, Kraft CT, et al. Defining the relationship between patient decisions to undergo breast reconstruction and contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2015;135(3):661–670. | ||

Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(22):2618–2624. | ||

Peralta EA, Ellenhorn JD, Wagman LD, Dagis A, Andersen JS, Chu DZ. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy improves the outcome of selected patients undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer. American Journal of Surgery. 2000;180(6):439–445. | ||

Herrinton LJ, Barlow WE, Yu O, et al. Efficacy of prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer: a cancer research network project. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(19):4275–4286. | ||

Bedrosian I, Hu CY, Chang GJ. Population-based study of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and survival outcomes of breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102(6):401–409. | ||

Brewster AM, Bedrosian I, Parker PA, et al. Association between contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and breast cancer outcomes by hormone receptor status. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5637–5643. | ||

Chung A, Huynh K, Lawrence C, Sim MS, Giuliano A. Comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and unilateral total mastectomy in breast cancer patients. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2012;19(8):2600–2606. | ||

Yao K, Winchester DJ, Czechura T, Huo D. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and survival: report from the National Cancer Data Base, 1998–2002. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;142(3):465–476. | ||

Kruper L, Kauffmann RM, Smith DD, Nelson RA. Survival analysis of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a question of selection bias. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2014;21(11):3448–3456. | ||

Boughey JC, Hoskin TL, Degnim AC, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is associated with a survival advantage in high-risk women with a personal history of breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2010;17(10):2702–2709. | ||

Lostumbo L, Carbine N, Wallace J, Ezzo J. Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004;(4):CD002748. | ||

Lee JS, Grant CS, Donohue JH, Crotty TB, Harmsen WS, Ilstrup DM. Arguments against routine contralateral mastectomy or undirected biopsy for invasive lobular breast cancer. Surgery. 1995;118(4):640–647; discussion 647–648. | ||

Boughey JC, Hoskin TL, Hartmann LC, et al. Impact of reconstruction and reoperation on long-term patient-reported satisfaction after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(2):401–408. | ||

Liederbach E, Piro R, Hughes K, Watkin R, Wang CH, Yao K. Clinicopathologic features and time interval analysis of contralateral breast cancers. Surgery. 2015;158(3):676–685. | ||

Font-Gonzalez A, Liu L, Voogd AC, et al. Inferior survival for young patients with contralateral compared to unilateral breast cancer: a nationwide population-based study in the Netherlands. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2013;139(3):811–819. | ||

Vichapat V, Garmo H, Holmberg L, et al. Prognosis of metachronous contralateral breast cancer: importance of stage, age and interval time between the two diagnoses. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2011;130(2):609–618. | ||

Vichapat V, Garmo H, Holmqvist M, et al. Tumor stage affects risk and prognosis of contralateral breast cancer: results from a large Swedish-population-based study. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(28):3478–3485. | ||

Liederbach E, Sisco M, Wang C, et al. Wait times for breast surgical operations, 2003–2011: a report from the National Cancer Data Base. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(3):899–907. | ||

Heemskerk-Gerritsen BA, Rookus MA, Aalfs CM, et al. Improved overall survival after contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with a history of unilateral breast cancer: a prospective analysis. International Journal of Cancer. Journal International du Cancer. 2015;136(3):668–677. | ||

Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(11):812–822. | ||

van der Kolk DM, de Bock GH, Leegte BK, et al. Penetrance of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 families: high cancer incidence at older age. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;124(3):643–651. | ||

Verhoog LC, Brekelmans CT, Seynaeve C, et al. Survival in hereditary breast cancer associated with germline mutations of BRCA2. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17(11):3396–3402. | ||

Weischer M, Nordestgaard BG, Pharoah P, et al. CHEK2*1100delC heterozygosity in women with breast cancer associated with early death, breast cancer-specific death, and increased risk of a second breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(35):4308–4316. | ||

Kriege M, Hollestelle A, Jager A, et al. Survival and contralateral breast cancer in CHEK2 1100delC breast cancer patients: impact of adjuvant chemotherapy. British Journal of Cancer. 2014;111(5):1004–1013. | ||

Pesce C, Liederbach E, Wang C, Lapin B, Winchester DJ, Yao K. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy provides no survival benefit in young women with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2014;21(10):3231–3239. | ||

Portschy PR, Kuntz KM, Tuttle TM. Survival outcomes after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a decision analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;106(8):dju160. | ||

Fayanju OM, Stoll CR, Fowler S, Colditz GA, Margenthaler JA. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy after unilateral breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Surgery. 2014;260(6):1000–1010. | ||

Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Lynch HT, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(6):1055–1062. | ||

Rosenberg SM, Tracy MS, Meyer ME, et al. Perceptions, knowledge, and satisfaction with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among young women with breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(6):373–381. | ||

Abbott A, Rueth N, Pappas-Varco S, Kuntz K, Kerr E, Tuttle T. Perceptions of contralateral breast cancer: an overestimation of risk. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2011;18(11):3129–3136. | ||

Soerjomataram I, Louwman WJ, Lemmens VE, de Vries E, Klokman WJ, Coebergh JW. Risks of second primary breast and urogenital cancer following female breast cancer in the south of The Netherlands, 1972–2001.European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41(15):2331–2337. | ||

Gao X, Fisher SG, Emami B. Risk of second primary cancer in the contralateral breast in women treated for early-stage breast cancer: a population-based study. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2003;56(4):1038–1045. | ||

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, et al. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2010;11(12):1135–1141. | ||

Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV Jr, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(12):1564–1569. | ||

Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ, et al. Four-year follow-up of trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: joint analysis of data from NCCTG N9831 and NSABP B-31. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(25):3366–3373. | ||

Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103(6):478–488. | ||

Reiner AS, John EM, Brooks JD, et al. Risk of asynchronous contralateral breast cancer in noncarriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with a family history of breast cancer: a report from the Women’s Environmental Cancer and Radiation Epidemiology Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(4):433–439. | ||

Pilewskie M, Olcese C, Eaton A, et al. Perioperative breast MRI is not associated with lower locoregional recurrence rates in DCIS patients treated with or without radiation. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2014;21(5):1552–1560. | ||

McCormick B, Winter K, Hudis C, et al. RTOG 9804: a prospective randomized trial for good-risk ductal carcinoma in situ comparing radiotherapy with observation. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(7):709–715. | ||

Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771–784. | ||

Musiello T, Bornhammar E, Saunders C. Breast surgeons’ perceptions and attitudes towards contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2013;83(7–8):527–532. | ||

Soran A, Ibrahim A, Kanbour M, et al. Decision making and factors influencing long-term satisfaction with prophylactic mastectomy in women with breast cancer. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2015;38(2):179–183. | ||

Han E, Johnson N, Glissmeyer M, et al. Increasing incidence of bilateral mastectomies: the patient perspective. American Journal of Surgery. 2011;201(5):615–618. | ||

Fisher CS, Martin-Dunlap T, Ruppel MB, Gao F, Atkins J, Margenthaler JA. Fear of recurrence and perceived survival benefit are primary motivators for choosing mastectomy over breast-conservation therapy regardless of age. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2012;19(10):3246–3250. | ||

Parker PA, Peterson SK, Bedrosian I, et al. Prospective study of surgical decision-making processes for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with breast cancer. Annals of Surgery. 2016;263(1):173–183. | ||

Frost MH, Schaid DJ, Sellers TA, et al. Long-term satisfaction and psychological and social function following bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(3):319–324. | ||

Frost MH, Hoskin TL, Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, Johnson JL, Boughey JC. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: long-term consistency of satisfaction and adverse effects and the significance of informed decision-making, quality of life, and personality traits. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2011;18(11):3110–3116. | ||

Montgomery LL, Tran KN, Heelan MC, et al. Issues of regret in women with contralateral prophylactic mastectomies. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 1999;6(6):546–552. | ||

Koslow S, Pharmer LA, Scott AM, et al. Long-term patient-reported satisfaction after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and implant reconstruction. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2013;20(11):3422–3429. | ||

Unukovych D, Sandelin K, Liljegren A, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in breast cancer patients with a family history: a prospective 2-years follow-up study of health related quality of life, sexuality and body image. European Journal of Cancer. 2012;48(17):3150–3156. | ||

Geiger AM, West CN, Nekhlyudov L, et al. Contentment with quality of life among breast cancer survivors with and without contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(9):1350–1356. | ||

Geiger AM, Nekhlyudov L, Herrinton LJ, et al. Quality of life after bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2007;14(2):686–694. | ||

Arrington AK, Jarosek SL, Virnig BA, Habermann EB, Tuttle TM. Patient and surgeon characteristics associated with increased use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in patients with breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2009;16(10):2697–2704. | ||

Yao K, Belkora J, Sisco M, et al. Survey of the deficits in surgeons’ knowledge of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. JAMA Surgery. 2016;151(4):391–393. | ||

Sharpe SM, Liederbach E, Czechura T, Pesce C, Winchester DJ, Yao K. Impact of bilateral versus unilateral mastectomy on short term outcomes and adjuvant therapy, 2003–2010: a report from the National Cancer Data Base. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2014;21(9):2920–2927. | ||

Gagliato Dde M, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Lei X, et al. Clinical impact of delaying initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(8):735–744. | ||

Crosby MA, Garvey PB, Selber JC, et al. Reconstructive outcomes in patients undergoing contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;128(5):1025–1033. | ||

Miller ME, Czechura T, Martz B, et al. Operative risks associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a single institution experience. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2013;20(13):4113–4120. | ||

Osman F, Saleh F, Jackson TD, Corrigan MA, Cil T. Increased postoperative complications in bilateral mastectomy patients compared to unilateral mastectomy: an analysis of the NSQIP database. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2013;20(10):3212–3217. | ||

Silva AK, Lapin B, Yao KA, Song DH, Sisco M. The effect of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy on perioperative complications in women undergoing immediate breast reconstruction: a NSQIP analysis. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(11):3474–3480. | ||

Roberts A, Habibi M, Frick KD. Cost-effectiveness of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for prevention of contralateral breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2014;21(7):2209–2217. | ||

Zendejas B, Moriarty JP, O’Byrne J, Degnim AC, Farley DR, Boughey JC. Cost-effectiveness of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy versus routine surveillance in patients with unilateral breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(22):2993–3000. | ||

Rosenberg SM, Sepucha K, Ruddy KJ, et al. Local therapy decision-making and contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in young women with early-stage breast cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(12):3809–3815. | ||

Kurian AW, Munoz DF, Rust P, et al. Online tool to guide decisions for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(5):497–506. | ||

Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(4):435–441. | ||

Street RL Jr, Voigt B, Geyer C Jr, Manning T, Swanson GP. Increasing patient involvement in choosing treatment for early breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;76(11):2275–2285. | ||

Goel V, Sawka CA, Thiel EC, Gort EH, O’Connor AM. Randomized trial of a patient decision aid for choice of surgical treatment for breast cancer. Medical Decision Making: An International Journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2001;21(1):1–6. | ||

Giuliano AE, Boolbol S, Degnim A, Kuerer H, Leitch AM, Morrow M. Society of Surgical Oncology: position statement on prophylactic mastectomy. Approved by the Society of Surgical Oncology Executive Council, March 2007. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2007;14(9):2425–2427. | ||

NCCN Guidelines. 2015. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#site. Accessed 2015. | ||

Frost MH, Slezak JM, Tran NV, et al. Satisfaction after contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: the significance of mastectomy type, reconstructive complications, and body appearance. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(31):7849–7856. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.