Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 7

Concurrent sexual partnerships among married Zimbabweans – implications for HIV prevention

Authors Mugweni E, Pearson S, Omar M

Received 20 May 2015

Accepted for publication 8 July 2015

Published 29 September 2015 Volume 2015:7 Pages 819—832

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S88884

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Elie Al-Chaer

Esther Mugweni,1 Stephen Pearson,2 Mayeh Omar2

1UCL Department of Infection and Population Health, University College London, London, 2The Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Background: Concurrent sexual partnerships play a key role in sustaining the HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe. Married couples are at an increased risk of contracting HIV from sexual networks produced by concurrent sexual partnerships. Addressing these partnerships is an international HIV prevention priority.

Methods: Our qualitative study presents the socioeconomic factors that contribute to the occurrence of concurrent sexual partnerships among married people in Zimbabwe. We conducted 36 in-depth interviews and four focus group discussions with married men and women in Zimbabwe in 2008 to understand the organizations of concurrent sexual partnerships. Data were analyzed using framework analysis.

Results: Our study indicates that relationship dissatisfaction played a key role in the engagement of concurrent sexual partnerships. Depending on the source of the dissatisfaction, there were four possible types of concurrent sexual relationships that were formed: sex worker, casual partner, regular girlfriend or informal polygyny which was referred to as “small house”. These relationships had different levels of intimacy, which had a bearing on practicing safer sex. Participants described three characteristics of hegemonic masculinity that contributed to the sources of dissatisfaction leading to concurrent sexual activity. Similarly, various aspects of emphasized femininity were described as creating opportunities for the occurrence of concurrent sexual relationships. Economic status was also listed as a factor that contributed to the occurrence of concurrent sexual partnerships.

Conclusion: Marital dissatisfaction was indicated as a contributing factor to the occurrence of concurrent sexual relationships. There were several reports of satisfying marital relationships in which affairs did not occur. Lessons from these marriages can be made part of future HIV prevention interventions targeted at preventing concurrent sexual partnerships by married couples.

Keywords: concurrent sexual partnerships, HIV, marriage

Introduction

Zimbabwe has successfully managed to reduce the estimated prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15–49 years from 29.3% in 1999 to 15% in 2011.1,2 Reduction in multiple sexual partners is identified as one of the factors that contributed to the decline in HIV prevalence in the country.2,3 It is hypothesized that concurrent sexual partnerships contribute to sustaining the epidemic in Zimbabwe, which is still largely driven by heterosexual contact.1,4 According to the Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey, 0.7% of married women and 14% of married men reported concurrent sexual activity between 2010 and 2011.5 However, the survey did not compare the HIV status of those who reported concurrency and those who did not.

Demographic data from 16 countries examining how marital concurrency contributes to the HIV epidemic suggest that marital concurrency increases the odds of acquiring HIV for couples.6 Although there is much debate about the role of multiple concurrent sexual partnerships on the HIV epidemic,4,7,8 evidence from Zimbabwe and other countries supports the notion that concurrency increases the risk of acquiring HIV through development of sexual networks in which the occurrence of unprotected sexual contact with an HIV-infected person puts both the person practicing concurrency and their partner at higher odds of acquiring HIV.4,9–12

Given the significant role of multiple sexual partners in sustaining the HIV epidemic, reducing sexual HIV transmission is an international HIV prevention priority.2,13 To this end, one of the key HIV prevention strategies in Zimbabwe is addressing multiple concurrent sexual partnerships, particularly among married people, who are considered as being at significantly higher risk of acquiring HIV through this practice.13–15 Effective HIV prevention could benefit from an understanding of the motivations for concurrent sexual partnerships by married people. This study contributes to a growing body on literature providing insight on the motivations for concurrent sexual partnerships.16–19 Our working definition of concurrency matched the UNAIDS definition, ie, these are overlapping sexual partnerships in which sexual intercourse with one partner occurs between two acts of intercourse with another partner.12

Our present study aimed to develop interventions to empower married Zimbabwean women to negotiate for safer sex. This paper addresses one of the research objectives, which is to describe and explain the occurrence of concurrent sexual activities by married Zimbabwean men and women. In this paper, we describe the sociocultural context in which monogamous married men and women made transitions into and out of concurrent sexual partnerships. We explore the organization of concurrent sexual partnerships as well as the socioeconomic factors that structured married men and women’s opportunities for engaging in extramarital sex. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Leeds Institute of Health Sciences Ethical Committee and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/1493).

Materials and methods

We provide a summary of our research methodology here as the full study is described elsewhere.20 The aim of this study was to identify socioculturally and organizationally feasible interventions for empowering married Zimbabwean women to negotiate for safer sex. We collected qualitative data over three phases. Written informed consent to take part was obtained from all participants. The first phase consisted of interviews with HIV prevention program implementers. In the second phase, we conducted four focus groups and 36 interviews with married men and women. Participants were defined as married if they had had a customary, court, or church wedding, or if they have been cohabiting for a long time. This is the standard definition also used for the Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey.5 In the third phase of our study, we conducted further interviews with HIV prevention implementers to investigate the organizational or sociocultural feasibility of implementing some of the suggested interventions from the second phase.

This paper is based on the second phase of the study, which was conducted between October and December 2008. We used intensity sampling to recruit participants from an HIV prevention nongovernmental organization, a faith-based organization, and an anti-domestic violence organization. Subsequent participants were recruited using snowballing. The first author collected data from all female participants; similarly, for cultural sensitivity, a male research assistant was employed to collect data from male participants during the second phase. Another Zimbabwean study also used male interviewers to collect information on sexual health from Zimbabwean men.21 The research assistant was a social scientist with postgraduate qualifications and had 8 years’ experience in sexual health research at the time of data collection. We also hired a male and female researcher to facilitate the male and female focus group discussions, respectively. The male focus group facilitator had been working on qualitative research of a similar nature with the male research assistant. The female focus group facilitator was an experienced social scientist educated to postgraduate level with extensive qualitative research experience in the HIV field. Despite the team’s research experience, the first author provided qualitative research and study-specific training in Harare before data collection. Competency was assessed after training during the pilot data collection.

All the data were collected using an agreed interview guide and focus group guide which were developed using findings from an extensive literature review and the conceptual framework for the study.20 The instruments were also developed using some findings that emerged from data collected in the first phase. During the actual data collection, the first author continued to provide support by having daily meetings with the team. While a few interviews were done in English, most of the interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in Shona. Direct verbatim translation rather than contextual translation was done simultaneously with transcription into a computer soon after data collection. Contextual translation was only used when direct translation was not meaningful.22,23 NVivo 8 software was used for data management and to aid our analysis, which used a framework approach.24,25 We began by familiarizing ourselves with the collected data using the transcripts of two focus groups and ten interviews. This allowed us to develop a thematic framework for coding the data which we went on to apply to the data.25 NVivo 8 enabled us to sort the data so that data with similar content were located together. This allowed scrutiny of the data in order to develop the descriptive and explanatory accounts.24,25 We used anonymized quotations to illustrate descriptive and explanatory findings.25

Results

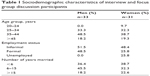

Thirty-three men and 31 women participated in the second phase of the study, and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of interview and focus group discussion participants |

Narratives by male and female participants appeared to indicate that concurrent sexual activity occurred in a cycle made up of four stages as shown in Figure 1. This cycle is not meant to be comprehensive but rather broad enough to capture the important aspects of extramarital affairs that were described. The process of separating the stages of the extramarital affair into discrete stages, though based on logical development of analysis, is somewhat artificial to us because of the significant overlap between the stages. Furthermore, it was possible to exit or terminate the cycle at different stages, as indicated in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Cycle of extramarital relationships. |

The idea that extramarital affairs occurred in a cycle was brought into sharp focus in the first female interview. In response to the question as to whether or not her husband had had an extramarital affair, Maryanne described Chris’ dissatisfaction with their sexual life, which she thought had pushed him into the “arms of another woman”. She explained how he had hidden the affair. She accidentally stumbled upon a text message in his telephone from his girlfriend. When Maryanne called the woman, she discovered they had been having an affair for over a year. After she confronted Chris about the affair, he ended it. Six months later, he resumed the affair.

Thereafter, in each interview, we sought for a chronology of extramarital affairs in order to establish if there was a pattern of how they occurred.

Almost all reports on concurrent sexual activity reported that some kind of dissatisfaction initiated affairs, as indicated in Figure 1. However, the idea that dissatisfaction initiated an affair implies a rational decision-making about whether to have extramarital sex and does not account for the more spontaneous and “irrational” context for some sexual behavior, such as when one is intoxicated. Nevertheless, there were two types of dissatisfaction described by participants. Some described acute dissatisfaction that was a product of temporarily unmet needs in the marriage. Other participants described chronic dissatisfaction with the spouse. Similar studies in Zimbabwe and Tanzania also indicate that dissatisfaction about various aspects of the marriage may result in concurrent sexual activity.19,26,27 This is in contrast with studies in Nigeria and Uganda in which affairs occurred despite marital satisfaction.28,29

Contrary narratives were given by some participants who reported that even though they were sometimes dissatisfied with their marriage, they did not engage in affairs. They reported being able to have respectful, frank discussions about the sources of the dissatisfaction with their spouse and jointly addressing the dissatisfaction.

Depending on the source of dissatisfaction, different types of extramarital relationships were developed, as described in the next section. The complexities of these relationships were highlighted by men who reported finding potential partners but choosing not to go ahead with the affair due to potential feelings of guilt or anxiety about being caught. It would have been useful to know how the desires or emotions of extramarital partners affected the decision not to proceed with an affair. However, we did not explore them in this study.

Reports of secrecy and deception once extramarital affairs commenced were common and this formed stage 3, as shown in Figure 1. Participants described husbands pretending to be monogamous (“acting like nothing is happening”) by ensuring that their conduct did not raise suspicion through calls or text messages from sexual partners, infrequent sex, sudden frequent business trips, or working late. As such stories were told of infidelity occurring while the deliberate lack of detectable change in a husband’s behavior caused wives to presume that they were mutually monogamous. Such presumptions have been noted in earlier studies, both in terms of married women being the last to know about an affair and only discovering affairs after diagnosis of HIV.30 Contrasting findings from studies in Nigeria and Uganda indicate that a married woman may know about her husband’s infidelity, even when he is secretive, but willingly ignores the infidelity.28,29

However, in our study, deception and secrecy were important aspects of affairs. Deception of a spouse was explained as being necessary to protect the marriage from the stigma and trauma of divorce. Having said this, not all men were secretive about their affairs. Openness about extramarital affairs often occurred in marriages where the man thought he had proprietary rights over his wife, as described in our previous study.20 This sometimes resulted in denigration of women, as explained by Mary:

My husband used to receive phone calls from his girlfriends in my presence and discuss unheard of sexual details (zvinhu zvisingaite) with them! Maybe they did it to hurt me. Because I thought I was worthless. I just ignored them. (Female interview respondent, aged 44 years).

The final stage of the affair was when the dissatisfaction was addressed, as shown in Figure 1. Once the dissatisfaction was perceived to be addressed, there appeared to be two possible outcomes. The extramarital relationship could be terminated if the need or needs that had been unmet were perceived to be fully addressed in the marriage. For example, Mary in the earlier excerpt explained that after 4 years of marital counselling, their emotional and sexual relationship was more satisfying and she felt her husband had become monogamous. Other discourses on terminating affairs centered on surreptitious affairs being discovered or nearly being discovered. For other men, termination of the affair occurred when the extramarital partner discovered that they were married. However, when the need was still unmet in the marriage, dissatisfaction would cause the cycle of extramarital affairs to continue.

Types of extramarital relationships

In this study, participants described four types of concurrent sexual relationships, ie, sex worker, casual partner, regular girlfriend, and “small house” partner. Other qualitative studies on concurrent sexual activity in African marriages have documented differences in types of extramarital relationships.28,29,31 Even though these are distinct types of concurrent sexual relationships, participants reiterated that these relationships were not always mutually exclusive. For example, some men were said to have extramarital relations with a small house, girlfriend, and sex workers concurrently. On the other hand, the extramarital partners were capable of having concurrent sexual relationships of their own, in which the same woman could be a casual partner, sex worker, girlfriend, or small house to different men, thus creating complex and risky sexual networks.

Sex worker

Firstly, a sex worker relationship was depicted as a temporary relationship between a client and a sexual services provider. Some participants called this relationship “short time”. It occurred when a man met a sex worker in a nightclub, bar, on the streets, or in a “brothel/lodge” and the man paid for sex. The encounter would be brief (as the metaphor “short time” suggests) and was reported (as noted in other qualitative studies on sex work in South Africa and Madagascar32,33) as a business transaction for both the sex worker and the client. Participants explained that for the sex worker the relationship was about money and for the client, sexual pleasure. There was no expectation on either side of emotional intimacy, although such feelings could develop.

Casual partner

There was a report of another type of casual sexual relationship which stemmed from existing friendships or acquaintances. In one such report, Gerry’s wife had casual sex with his best friend because she was sexually dissatisfied due to his prolonged absence from home. He was unsure but suspected that she got payment for sex because of their low financial status. Other forms of casual sex did not involve monetary payment and were just one-off incidents.

Regular partner/girlfriend

The development of emotional intimacy marked the vague transition from casual partner or sex worker to regular sexual partner as described by Richard:

The problem with men is that we love prostitutes. It is right for us to do so. But we have a problem that if you have sex with Peggy today and tomorrow … on the third day you say to Peggy, “Ah Peggy, we have now become familiar with each other (tajairirana). We are fine” It is now Peggy and you straight man to woman [ie, having unprotected sex] and there is no protection from infection! (Male interview respondent, aged 37 years).

Here, Richard suggested that going to the same prostitute three times gave both of them a sense of familiarity (tajairirana). In the group discussions, men argued that it was “impossible” to use condoms with the same casual partner or sex worker after a few episodes of sex. While money was involved with the sex worker, it was not viewed as direct payment for sex but given as financial support. In the narratives, this was because such a woman was no longer just a sex worker. This finding supports the sawtooth hypothesis, which posits that within a close relationship condom use will decrease over time, creating a sawtooth pattern.34 Previous epidemiological studies suggest that repeated sexual encounters with sex workers rather than one-off encounters is a more significant driver of the HIV epidemic in Africa as compared with countries like Thailand and the USA.35

As we analyzed the data, we inferred that the emotional attachment was a mutual experience which resulted in some form of mutual trust and a consequent decrease in condom use. It can be inferred that these relationships carried a higher risk of HIV transmission than with casual encounters with sex workers because of the reduced condom use.

“Small house” partner

The fourth extramarital relationship was “small house” (that is, the man forms an additional smaller household with an extramarital partner). A “small house” was considered as informal polygyny because the relationship was considered to be “something permanent”. In all reports, the term “small house” referred to a woman and not a man. The transition from girlfriend to “small house” was vague, and the term “small house” was defined differently by participants, sometimes interchangeably with girlfriend. However, some men explained how “a “small house” was deeper than just sex worker or girlfriend. The term “small house” is not unique to Zimbabwe, and is used to describe similar extramarital liaisons in Tanzania.36 Apart from being a regular sexual partner, a man would provide materially for his “small house”, and condom use is nearly non-existent.

Emotional intimacy with a “small house” was greater than with a regular girlfriend. This was the only extramarital relationship in which love (rudo) and romance (kudanana) were mentioned. A man could have children with his “small house”. In some cases, the man’s extended family would be told of this second family. Other researchers indicate that men become officially polygamous when they eventually pay a bride price for the “small house”.26 Another difference between “small house” and girlfriend or sex worker was the expectation of sexual exclusivity from the “small house” by the man, even though he would continue sexual relations with his wife. However stories were told of “small houses” having multiple concurrent partners:

On the issue of “small houses” and safe sex … there can be two of you in the same “small house” – how safe is that? From what I know about men, you can use protection for about three times, after that you don’t use protection. There is no man who can use condoms on ten occasions with the same person, impossible! How safe are we gentlemen? If I and Samson have the same “small house” and we have our wives at home, how many people are we mixing sexually? (Male focus group participant, aged 40 years).

Here, Max pointed out the sexual mixing that potentially occurred with “small houses” and the increased risk of HIV, which is well documented in the literature.27,36,37 Participants showed an awareness of the risk of contracting HIV from a “small house” who had other concurrent partners. From their narratives, this extramarital relationship was perceived as carrying the greatest risk of exposure to HIV. While it is possible some men consistently used condoms for all extramarital relations, this was not represented in our study.

Having presented what extramarital relationships are, we now explore the factors that contributed to concurrent sexual activity. Two broad socioeconomic factors seemed to trigger dissatisfaction that contributed to frequency of concurrent sexual activity, ie, gender socialization and financial status.

Gender socialization

Our analysis identified collective identities for men and women that shaped concurrent sexual activity. Even though we use the term “collective identities”, the data contained several expressions of masculinity and femininity, to which people adhered to differently. In our analysis, we paid particular attention to how individuals acquired understanding of ideas, beliefs, and values on concurrent sexual activity through implicit and explicit messages about men and women in childhood and adolescence as suggested in previous studies on this subject.38

Masculinity

Participants’ reports highlighted that concurrent sexual activity achieved a socially recognized expression of hegemonic masculinity. While there are several characteristics of masculinity in the literature that result in concurrent sexual activity,21,38 participants described three characteristics of masculinity that contributed to concurrent sexual activity, ie, lust, needing frequent sex, and having satisfying sexual performance. In line with the plurality of masculinity, other characteristics of masculinity such as faithfulness to a spouse were cited as preventing concurrent sexual activity by participants.

Masculinity characterized by lust

Most participants attributed concurrent sexual activity to lust (ruchiva), ie, a masculine instinctive, uncontrollable desire for sex with multiple sexual partners. Literature reviews on African masculinity identify this as a mark of African hegemonic masculinity.36,38 Sex with multiple partners was described as a direct product of acting on lust. Participants explained lust in four ways: as a natural part of manhood, as a product of sexual activity before marriage, learned behavior, or evil spirits, as shown in Figure 2. These could operate at the same time, and we will describe how each resulted in lust.

| Figure 2 Participants’ explanations for men’s lust. |

A common explanation for lust was as a natural part of manhood using terms such as “created that way”, “an inborn thing”, and “naturally”.

I have extra marital affairs … I do not want to lie. I personally have sex with other people. The reasons … ah … If God could be talked to! These things were created like that… we can say that men were created like that. (Male interview respondent, aged 40 years).

These men reinforced their masculinity through extramarital affairs. This form of masculinity was accompanied by beliefs about how natural lust caused men to desire different sexual partners. According to participants, lust was triggered by various aspects of sexual appeal that could not all be contained in one wife at the same time. Consequently, this created the dissatisfaction that precipitated seeking out sexual partners. Participants with this belief argued that male faithfulness in the presence of other sexually appealing women was impossible:

Moderator: Does faithfulness work?

Trevor: I don’t know what exactly you mean by faithfulness. It is beyond my general understanding. But men naturally, the way we are created, we are not faithful. What is important is that I protect myself, in order to protect the rest. The kind of biblical faithfulness is too abstract because as men we are biological beings. We react when we see a beautiful woman, it doesn’t matter whether you go to church or not… Faithfulness is you using the condom so that your wife does not get to know what you have been doing…

Tsotsi: Have you ever noticed that as men sometimes we are not really serious about some things. We just do it (have affairs) on purpose (tinozviitisa) like we can’t help it. (Male, focus group discussion, younger and older men).

In this discussion, Trevor reiterates the point that lust made it impossible for men to be faithful. His belief was that faithfulness was demonstrated by using condoms with extramarital partners.

It has been argued that viewing gendered behaviors as products of natural factors does not explain diversity of sexual behavior among men or show that masculinity is constantly changing.39 For example, the view that men were created with natural lust seemed to change after an HIV-positive diagnosis. Several men who were living with HIV in our study stated that they had stopped lusting for multiple sexual partners because they feared re-infection with HIV. They reconfigured masculinity to suit their HIV diagnosis.

Lust was also explained as a product of subconsciously learned behavior, as shown in Figure 2. Some participants explained that the traditional practice of polygyny, as observed in older male relatives, reinforced the idea that it was acceptable for men to lust for and have multiple sexual partners. In contrasting accounts, some participants explained how they had seen great-grandfathers with several wives but did not use this as a basis for engaging in extramarital affairs. This was attributed to the fact their great-grandparents had lived in an era free from the risk of HIV. However, there was a potential risk of sexually transmitted infections that men still faced from extramarital affairs.

Some male and female participants explained how lust was a trait that began when one was an adolescent, as shown in Figure 2. In adolescence, African male sexual prowess may be shown by having multiple partners.38–40 Others argue that the sexual socialization practiced in adolescence shapes sexual interactions in adulthood.38 Several participants explained that men who had multiple sexual partners before marriage were more likely to find monogamy difficult because of being accustomed to multiple sexual partners. This was said to cause chronic dissatisfaction with one wife. Similar explanations were noted in an analysis of survey data from Côte d’Ivoire, Tanzania, Zambia, and Thailand, which showed that the number of premarital partners was associated with increased probability of extramarital sex later in life.41

Lust for multiple sexual partners was also explained as the product of the influence of evil spirits, as shown in Figure 2. These evil spirits (shave) were said to influence and make men dissatisfied with one woman and increase an individual’s sexual appetites for different women. Consequently, it can be inferred that a person had no real responsibility for their actions because their mind, will, and actions were taken over by evil spirits. This fits in with the role of spirits in traditional Zimbabwean culture and such explanations for sexual behavior have also been documented in other Zimbabwean studies.21,27

Masculinity characterized by enjoying satisfying sexual performance

In participants’ descriptions, enjoying satisfying sexual performance from a woman reinforced manhood. Narratives on this indicated that satisfying sexual performance had to have four crucial defining features:

- Creativity – this was equated to pleasurable variety in sexual activity.

- Comprehensiveness – this included vibrancy, uninhibitedness, spontaneity, adventure, excitement, and communication.

- Skillfulness – involved seeking and use of knowledge and skills that could improve the quality of the sex.

- Excellent presentation – for several men, great sexual performance involved a wife being physically attractive.

Some participants explained how satisfying sexual performance that could be obtained from a sex worker, a girlfriend, or a “small house” was not the same as what some wives provided. When married women complied with femininity characterized by sexual passivity and asexuality, the consequent “boring” sexual performance by a wife was cited as a reason why men would be dissatisfied with their sexual relationship and thus engage in extramarital sex. To some men, sex was about a sexual partner showing competence in sexual performance rather than emotional or sexual intimacy. This was the reason why some men would have sex with sex workers whom they reported not to love but who provided them with the opportunity of satisfying sexual performance.

Masculinity characterized by having frequent sex

Frequent sex was deemed to be an important aspect of marriage by several male participants in this study. When manhood was asserted by having frequent sex, this created dissatisfaction with a wife when sex was infrequent. This was part of the reasoning behind having concurrent sexual activity to address this perceived unmet need. One man explained that when he was growing up he was told, “You must screw your wife a lot, screw her every day”. Hence when they were unable to have sex for prolonged periods, he would be dissatisfied with the marriage and concurrent sexual activity reinforced his manhood.

Masculinity characterized by faithfulness to a spouse

The dominant forms of masculinity described in the above sections were not the only forms of masculinity in the dataset. Another expression of masculinity was of faithfulness to a spouse. There were two explanations for this type of masculinity, ie, religion and leadership. Some of the men who were recruited from the faith-based organization indicated that sex was a divine gift limited to marriage. This sexual socialization and fear of God himself and or his judgment were the reasons they gave for monogamy. Other qualitative studies in Africa confirm how religion may cause men to reconfigure their masculinity from lusting for multiple partners to monogamy.27,38,42 Furthermore, men from the faith-based organizations described how masculinity in their social circles was reinforced by being a caring, faithful, respectful husband rather than infidelity, which was highly stigmatized. In other accounts, men described being in accountable, supportive mentorship relationships with other men in the church who supported them in fulfilling their roles as monogamous husbands.

Masculinity defined by faithfulness was also associated with being a leader in the community. Joe, for example, was a community development worker; he was well known and felt he was looked upon as an example of a faithful husband. He admitted that although he had had opportunities to have extramarital sex, he did not indulge in these for fear of losing his good reputation. His fears of being seen in a queue for treatment of sexually transmitted infections while professing the importance of faithfulness deterred him from affairs. Thus, he thought he would be more authentic as a leader if he lived the life that he was telling others in the community.

Femininity

Reflecting that heterosexual partnerships involve the interaction of a man and woman, participants identified various characteristics of emphasized femininity that also contributed to the occurrence of affairs. Reports were given of women resisting or complying with the characteristics of emphasized femininity shown in Figure 3 and this shaped the opportunities for concurrent sexual activity.

| Figure 3 Characteristics of emphasized femininity that shaped extramarital sexual activity. |

Femininity characterized by faithfulness to a husband

Emphasized femininity was sometimes demonstrated by being faithful to a husband as shown in Figure 3. Complying with this femininity reduced a wife’s opportunities to be involved in concurrent sexual activity. Traditionally it is a serious offence (mhosva) for a wife to have extramarital sex and this can result in public embarrassment, physical abuse, or divorce.43 The male participants whose wives had had affairs, Gerry and Ronald, bore witness to these consequences of female infidelity. After Gerry discovered his wife’s infidelity he divorced her and remarried. Ronald reported publicly embarrassing his adulterous wife to their extended family and summoning her lover to civil court to get compensation (kuripa) from him but he did not divorce her.

Another respondent, Christine, explained how she preferred to be “judged (kutongwa)” by people for being left by her husband rather than to be judged for having extramarital affairs, implying that society gave a harsh judgement on female extramarital affairs. Women said divorce was accompanied by losing respect in the community, gossip, and condemnation for not complying with emphasized femininity. This may explain why none of the interviewed women admitted to having or having had an affair. However, this is not to say that concurrent sexual activity does not occur among married women. Femininity characterized by faithfulness to a husband was also associated with fear of contracting HIV:

Interviewer: You mentioned that you went for 2 months without having sex, and you were sexually dissatisfied. Did you ever think of looking for somebody who could satisfy your sexual needs?

Julie: I was afraid of things that are out there … diseases. I said, “If I go out there, what if I come back with HIV?” I was afraid. I thought of an affair, I don’t want to lie because as a person there are some things you desire but I was afraid. (Female interview respondent, aged 30 years).

Despite Julie’s dissatisfaction with the sex in her marriage, she made the choice not to have an affair because she was afraid of HIV. Participants also reported that femininity characterized by faithfulness was associated with religious teachings on monogamy. This was because some women held strong religious beliefs and chose to act on the biblical teachings on monogamy. These narratives were very similar to those of men described earlier who reported being socialized to view sex as a divine gift confined to marriage.

Femininity characterized by tolerance of a husband’s infidelity

Women described sexual socialization by influential women such as aunts, mothers, and grandmothers about how men were naturally unfaithful. Emphasized femininity prepared women for the inevitability of male infidelity. For example, Jessica explained how the first time her husband had an affair, she was heartbroken. However, after hearing similar stories from other women, she accepted his behavior as normal:

When you listen to the circumstances from other people you say … ah men do these things (have extramarital affairs)! Why should I expect my husband to be different … so you just accept that this is how men are. (Female interview respondent, aged 27 years).

Some authors have suggested that excusing male infidelity is an integral part of emphasized African femininity and is essential for avoiding divorce, which in itself is highly stigmatized.36 However, not all respondents tolerated male infidelity. Some women threatened divorce or went to report husband’s affairs to his extended family. In other studies, women reacted to a discovered affair by engaging in revenge sex.28

Femininity characterized by respect and submission to a husband

Informants indicated that resisting emphasized femininity characterized by submission and respect from husbands contributed to the occurrence of male extramarital affairs. When a wife was argumentative and disrespectful, this was given as a reason why a husband can be dissatisfied with the marriage and seek a more respectful partner. Other qualitative studies on concurrent sexual activity in East Africa and Zambia echo this finding.36,40

One respondent, Tsitsi, caught her husband having sex with another woman. In her anger she went to the civil court to sue him for adultery. She reported that the judge told her that she deserved what was happening to her because she talked too much and her husband had to find solace in someone else.

In a contrasting report, Matthew explained that submission and respect were a mutual experience for him and his wife Sarah. Thus, when he felt disrespected by her, he interpreted this as an indication of unresolved conflict or problems. His approach was to discuss his feelings openly with her and if they failed to come to a consensus they would seek counselling from extended family or mature friends. Thus, affairs because of disrespect from Sarah were not an option.

Femininity characterized by active sexuality

Like masculinity, emphasized femininity in Zimbabwe is shifting, and this was reflected by narratives of reasons why women engaged in extramarital sex. Informants indicated that the sexual pleasure portrayed in novels or on television made some women dissatisfied with their marriages and thus engage in affairs in order to search for sexual pleasure. This has also been reported in a qualitative study on young women’s sexuality in Kenya.44

Even though none of the female participants admitted to concurrent sexual activity, discourses on female extramarital affairs portrayed redefining womanhood from asexuality to active sexuality, demonstrated by receiving sexual pleasure. Several women complied with femininity characterized by active sexuality. However, this was not always a basis for affairs but a basis to communicate specific sexual desires and needs to a husband. Nevertheless, this was only possible in marriages where effective sexual communication was established.

Economic status

Having presented how gender plays a role in the occurrence of extramarital relationships, we now explore economic status and its relationship to concurrent sexual activity. Male and female participants cited too much or too little money, to explain opportunities for concurrent sexual activity.

Wealth

In each of the four different types of extramarital relationships we described, availability of financial resources was described as an important aspect of the relationship. Each relationship had different financial implications, with “small houses” being the most expensive as they were like a second marriage. As such, wealth was cited as a reason for the occurrence of concurrent sexual relationships. Men who were described as wealthy were said to be more likely to address their dissatisfaction through affairs, as Samantha explained:

Interviewer: Why is her husband having an affair?

Samantha: She says he is going through a midlife crisis, but I think he is just like many men in Zimbabwe. When they make a lot of money they want a new house, a car renewal and a new woman. (Female interview respondent, aged 28 years).

Previous studies in Zimbabwe and Cameroon confirm that wealthy men are more likely to have concurrent sexual partners than poorer men.26,27,45 Traditionally, it is acceptable for African men to have more wives as they become wealthier.38,46 This may have socialized men to think that it is acceptable to have extramarital affairs once one is wealthy.

Equally, other studies have shown how men would find themselves being an attractive target for young women because of their wealth.28,46 However, this was not widely represented in the data, perhaps because of our lack of the views of women who were extramarital sexual partners. Having said this, we must point out that some wealthy men in this study reported no extramarital activity. Hence this is not an automatic association. Not having affairs when one was wealthy emerged from discourses of wealth not being what decided the principles by which they lived their lives but having a sense of self-worth with or without money, as explained by Zech:

We have agreed that money is just a visitor in our marriage which just comes and goes. We refuse to allow it to control how we live. (Male interview respondent, aged 49 years).

In the participants’ accounts, not all men were wealthy enough to have “small houses”. Thus, some men spoke of cheaper options, such as the occasional sex worker. Jonathan, for example, had a job as an IT technician and lived in the medium density suburbs in Harare. He explained how he and his friends did not have the expenses of permanent “small houses”, but when they would go out drinking they would just purchase sex from sexual workers.

For women married to wealthy men, the propensity to have concurrent sexual relationships was explained as a consequence of emotional neglect by their husbands. Nancy, for example, stated how rich men expected their wives to be content with big houses and fancy cars. In her opinion, this was not enough because women needed affection and companionship. Consequently, when a husband provided materially but not emotionally, this created the need to look for companionship in affairs. Stories were told of rich women having affairs with their workers because of the need for sexual pleasure and companionship. However, other wealthy women in this study spoke of being neglected by their husbands but desisting from affairs by devoting their time, energy, and affection on their children or engaging in charity work.

Poverty

Some participants reported the potentially emasculating effects of when a man was unemployed or unable to provide for his family. Studies on African masculinity confirm that when manhood is defined by being able to provide for a family, it presents a challenge to the man, who may feel less of a man because of poverty.36,38 One female respondent explained that in the harsh economic climate in Zimbabwe at the time of the data collection, when many men were having financial difficulties, it was crucial for a wife not to belittle the husband as this could bruise his ego.

Some women showed awareness of this fragility of masculinity. They reported that failure to be sensitive could possibly result in an emasculated man looking for extramarital affairs in which women appreciated him and “rubbed his ego the right way”. In a South African study of sex workers, participants spoke of how they treated clients with respect for being a patron of their business.47 It may be inferred that men liked the respect and not just sex from sex workers. Our informants explained that poor men sometimes got overexcited on the occasional times that they had money. This resulted in concurrent sexual relationships, particularly with sex workers, as recounted by Marlon:

When I would get money! I would forget my name, where I am coming from and where I am going! I would start having a lot of women friends. I would call myself Mr Point and Shoot. I would give myself that name because whomever I would point at I would have a shot at. (Male interview respondent, aged 45 years).

Some male participants quoted narratives of poor married women who would sometimes borrow money from men and then pay the debt through sex. Participants spoke of how such women may be forced into concurrent sexual activity as “survival sex” in order to provide the basic needs for their family (for example, food or school fees for children). This sex has been termed “survival” or “transactional” sex by other authors, and is sex to meet basic human needs.46 The harsh economic climate at the time of data collection likely made women vulnerable to “survival sex”.

Discussion

Before discussing the findings, we will mention a few issues about the quality of the data. Reporting concurrency, like other sexual behaviors, may be affected by social desirability, recall bias, or avoiding disclosures that might cause embarrassment.48,49 Given the intensely personal nature of the data collected, we reassured participants of confidentiality and anonymity before, during, and after data collection. Nevertheless, none of the female participants admitted to extramarital sex. Furthermore, only two men admitted that their wives had had affairs. However, there is evidence from nationally representative studies to suggest that extramarital affairs occur among married Zimbabwean women, albeit five times less likely than among married men.31 This underreporting may be because known or suspected extramarital affairs by women are socially unacceptable, and are associated with high levels of physical abuse by husbands, including reports of homicide in Zimbabwe.43 Hence our study is limited in that the descriptions of extramarital relations are largely based on male and female participants’ reports of men’s extramarital relations.

Secondly, our study is limited by omitting reports of the desires, emotions, and perspectives of men’s extramarital partners. As such, this paper may read as though men solely determined if and how extramarital affairs occurred. This may not be a full and accurate portrayal of what happens in these relationships, as documented in previous studies in Zimbabwe and other parts of Africa.26,28,32,46 These studies indicate that married men’s sexual partners have their own motives for initiating or accepting sexual relationships with married men. Wherever possible, we have paid attention to reported second-hand perspectives of extramarital partners, but this is very limited.

Despite these limitations, this study has explored the socioeconomic context in which monogamous men or women make a transition into and out of concurrent sexual partnerships. The findings reveal a range of opportunities for HIV interventions to address concurrent sex by married people. Within marriage there may be periods when either one or both spouses feel dissatisfied with various aspects of the relationship. While some spouses were able to communicate and resolve dissatisfaction, others found this communication difficult, as supported in the literature.30,50,51 Dissatisfaction if unaddressed was said to trigger extramarital affairs, as indicated in previous research.19,26,27 This finding is contrary to the popular view that men have extramarital affairs just because they are male. A key message from our study is that the root cause of concurrent sexual activity is dissatisfaction and that this dissatisfaction can be triggered by various factors.

Dissatisfaction that stemmed from masculine ideologies characterized by receiving satisfying sexual performance or frequent sex could potentially be addressed by communicating openly about necessary changes in the quality and quantity of sex, and could be resolved through targeted communication interventions. Nevertheless, other causes of dissatisfaction were harder to deal with; for example, the belief that men have an innate natural overpowering lust for sex with different sexual partners. The dissatisfaction resulting from these factors may be much harder to resolve in the confines of a couple because these are a product of beliefs operating at a society level. Hence these beliefs may be addressed through community education as the HIV epidemic has been a driver for reconsideration of risky gendered behaviors and attitudes.39

Future HIV interventions could target the complex structure of affairs. The formation of affairs was such that they were mostly secretive. This secrecy makes it difficult to introduce appropriate safer sexual practices within marriage. Given that confessing involvement in an extramarital affair may be difficult, emotionally distressing, or lead to divorce, HIV prevention could emphasize consistent safer sex practice in extramarital relationships. Even this is not without its challenges due to the highly fluid meanings of extramarital sexual relationships.

The findings indicate that one-off sexual encounters with sex workers were viewed as brief business transactions in which sexual pleasure was exchanged for money and condom use was reported to be consistent. This finding is consistent with a study that reviewed national epidemiological data to explain the decline in HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe.3 Nevertheless, some men sometimes visited the same sex worker several times and the increased intimacy made condom use inconsistent. It is these repeat visits to sex workers and not one of encounters that mathematical models suggest results in an increased cumulative probability of contracting HIV from sex workers.35 HIV interventions to encourage condom use with casual partners must continue to be part of the strategy for negating the effects of extramarital relationships.

Regular sexual relationships were also formed with women who were not sex workers. Some of these partnerships eventually turned into “small houses” in which men provided emotional and material support to their lovers. Emotional intimacy made condom use almost non-existent. There was an expectation from respondents that the “small house” would be monogamous, but previous qualitative studies on this subject in Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and Kenya indicate that this is hardly the case.26,31,36 As such, these relationships may carry a high risk of contracting HIV because of the frequency of unprotected sex and partners lacking knowledge of each other’s HIV status.

Previous HIV interventions in Zimbabwe have focused on sex workers, hence the reported consistent condom use in those relationships.3 However, fewer interventions exist for other types of extramarital relationships. This is an area that must be addressed both from the perspective of the married men and from the perspective of the “small house” so that safer sex practices are increased. Such an intervention was being piloted in Zimbabwe, with mass media being used to target women who are “small houses” so that they can insist on safer sex practices.

Lessons can be learned from men who reported that they were monogamous. Their narratives indicate that people adhere to different versions of masculinity to different degrees and that masculinity is not static but can be reconfigured.38 This reconfiguration of masculinity was said to be a product of religious notions. Others reported marital and sexual satisfaction due to effective general and sexual communication with their wives, which removed the need for extramarital relationships. Religion has been linked with monogamy in other studies. However, there is a need to further refine our understanding of why some religious men have affairs and others remain monogamous.52 This would be a valuable learning point in HIV interventions in a place like Zimbabwe where Christianity is a major and influential part of the social fabric.5 Longitudinal quantitative data are needed to refine insights on predictive, moderating, and mediating factors for engagement in concurrent sexual relationships by married people.

Conclusion

Our study indicates that relationship dissatisfaction plays a key role in the engagement of concurrent sexual partnerships by married people in Zimbabwe. Depending on the source of the dissatisfaction, different types of relationships were formed. These relationships had different levels of intimacy, which had a bearing on practicing safer sex. Lessons can be learned from men and women who were able to maintain healthy, satisfying marital relationships. These lessons can be made part of future HIV interventions targeted at preventing concurrent sexual partnerships by married couples.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by a University of Leeds Overseas Research Student Award given to Esther Mugweni. We acknowledge the people and organizations who participated in this study. Thanks are extended to Thomasina Muchakwana, Rangarirai Tigere, and Alice Thole for their support with the field work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Munjoma MW, Mhlanga FG, Mapingure MP, et al. The incidence of HIV among women recruited during late pregnancy and followed up for six years after childbirth in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:668. | ||

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS report on the global epidemic 2013. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, et al. HIV decline associated with behavior change in Eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311(5761):664–666. | ||

Mah TL, Shelton JD. Concurrency revisited: increasing and compelling epidemiological evidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:33. | ||

Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2010–2011. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency Harare, Zimbabwe; ICF International, Inc. Calverton, MD, USA; 2012. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR254/FR254.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

Fox AM. Marital concurrency and HIV risk in 16 African countries. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):791–800. | ||

Lurie MN, Rosenthal S. Concurrent partnerships as a driver of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa? The evidence is limited. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):17–24. | ||

Sawers L, Stillwaggon E. Concurrent sexual partnerships do not explain the HIV epidemics in Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:34. | ||

Eaton JW, Takavarasha FR, Schumacher CM, et al. Trends in concurrency, polygyny, and multiple sex partnerships during a decade of declining HIV prevalence in Eastern Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 2014;210 Suppl 2:S562–S568. | ||

Goodreau SM, Cassels S, Kasprzyk D, Montaño DE, Greek A, Morris M. Concurrent partnerships, acute infection and HIV epidemic dynamics among young adults in Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):312–322. | ||

Mapfumo J, Shumba A, Zvimba R, Chinyanganya P. Sexual activity and prevalence of multiple sexual relationships among female students at a university campus in Zimbabwe. Anthropologist. 2012;14(5):383–391. | ||

UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling, and Projections: Working Group on Measuring Concurrent Sexual Partnerships. HIV: consensus indicators are needed for concurrency. Lancet. 2010;375(9715):621–622. | ||

Gouws E, Cuchi P; International Collaboration on Estimating HIV Incidence by Modes of Transmission. Focusing the HIV response through estimating the major modes of HIV transmission: a multi-country analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88 Suppl 2:i76–i85. | ||

National AIDS Council. Global AIDS response country progress report – Zimbabwe 2014. Harare, Zimbabwe: National AIDS Council; 2014. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/ZWE_narrative_report_2014.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

National AIDS Council. Zimbabwe National Behavioural Change Strategy 2006–2010. Harare, Zimbabwe: National AIDS Council; 2010. Available from http://www.nac.org.zw/sites/default/files/BC-strategy%28final%29.pdf | ||

Limaye RJ, Babalola S, Kennedy CE, Kerrigan DL. Descriptive and injunctive norms related to concurrent sexual partnerships in Malawi: implications for HIV prevention research and programming. Health Educ Res. 2013;28(4):563–573. | ||

Mavhu W, Langhaug L, Pascoe S, Dirawo J, Hart G, Cowan F. A novel tool to assess community norms and attitudes to multiple and concurrent sexual partnering in rural Zimbabwe: participatory attitudinal ranking. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):52–59. | ||

Ruark A, Dlamini L, Mazibuko N, et al. Love, lust and the emotional context of multiple and concurrent sexual partnerships among young Swazi adults. Afr J AIDS Res. 2014;13(2):133–143. | ||

Cox CM, Babalola S, Kennedy CE, Mbwambo J, Likindikoki S, Kerrigan D. Determinants of concurrent sexual partnerships within stable relationships: a qualitative study in Tanzania. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e003680. | ||

Mugweni E, Pearson S, Omar M. Traditional gender roles, forced sex and HIV in Zimbabwean marriages. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(5):577–590. | ||

Pearson S, Makadzange P. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual-health concerns: a qualitative study of men in Zimbabwe. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(4):361–376. | ||

Brislin R. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In: Triandis HC, Berry JW, editors. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology. Boston MA, USA: Allyn & Bacon; 1980. | ||

Larson M. Meaning-Based Translation: A Guide to Cross-Language Equivalence. Lanham, MD, USA: University Press of America and Summer Institute of Linguistics; 1998. | ||

Bazeley P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. London, UK: Sage Publications; 2007. | ||

Ritchie J, Spencer L, O’Connor W. Carrying out qualitative analysis. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, editors. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London, UK: Sage Publications; 2003. | ||

Chingandu L. Multiple concurrent partnerships: the story of Zimbabwe – are small houses a key driver? Harare, Zimbabwe: Southern African HIV and AIDS Information Dissemination Service; 2007. Available from: http://archive.kubatana.net/docs/hivaid/safaids_small_houses_070612.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

Taruberekera N, et al. Concurrent heterosexual partnerships, HIV risk and related determinants among the general population in Zimbabwe, 2009. Washington, DC, USA: Population Services International; 2009. Available from: | ||

Smith DJ. Modern marriage, men’s extramarital sex, and HIV risk in southeastern Nigeria. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):997–1005. | ||

Parikh S. The political economy of marriage and HIV: the ABC approach, ‘safe’ infidelity and managing moral risk in Uganda. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1198–1208. | ||

Feldman R, Maposhere C. Safer sex and reproductive choice: findings from “Positive women: voices and choices” in Zimbabwe. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(22):162–173. | ||

Taruberekera N, Jafa K. Multiple concurrent partnerships in Zimbabwe: determinants and monitoring indicators in social marketing research series 2008. Washington, DC, USA: Population Services International; 2008. Available from http://hdl.handle.net/1902.1/PEGGB. | ||

Campbell C. Letting them die: why HIV prevention programmes fail. Available from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2816/1/Why_HIV_prevention_programmes_fail_(LSERO).pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

Stoebenau K, Hindin MJ, Nathanson CA, Rakotoarison PG, Razafintsalama V. “... But then he became my sipa”: the implications of relationship fluidity for condom use among women sex workers in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):811–819. | ||

Ku L, Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH. The dynamics of young men’s condom use during and across relationships. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26(6):246–251. | ||

Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–775. | ||

Silberschmidt M. Male sexuality in the context of socio-economic change in rural and urban East Africa. Sexuality in Africa Magazine. 2005(2). Available from http://www.arsrc.org/downloads/sia/mar05/mar05.pdf. | ||

Green EC, Mah TL, Ruark A, Hearst N. A framework for sexual partnerships: risks and implications for HIV prevention in Africa. Stud Fam Plann. 2009;40(1):63–70. | ||

Barker G, Ricardo C. Young men and the construction of masculinity in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for HIV/AIDS, conflict and violence. Washington DC, USA: World Bank; 2005. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2005/06/6022525/young-men-construction-masculinity-sub-saharan-africa-implications-hivaids-conflict-violence. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

Jewkes R, Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(1):6. | ||

Simpson A. Sons and fathers/boys to men in the time of AIDS: learning masculinity in Zambia. J South Afr Stud. 2005;31(3):569–586. | ||

White R, Cleland J, Caraël M. Links between premarital sexual behaviour and extramarital intercourse: a multi-site analysis. AIDS. 2000;14(15):2323–2331. | ||

Hirsch JS, Meneses S, Thompson B, Negroni M, Pelcastre B, del Rio C. The inevitability of infidelity: sexual reputation, social geographies, and marital HIV risk in rural Mexico. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):986–996. | ||

Njovana E, Watts C. Gender violence in Zimbabwe: a need for collaborative action. Reprod Health Matters. 1996;7:46–55. | ||

Spronk R. Female sexuality in Nairobi: flawed or favoured? Cult Health Sex. 2005;7(3):267–277. | ||

Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS, Mbu RE, Nana P, Kouam L. Wealth and sexual behaviour among men in Cameroon. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2006;6:11. | ||

Luke N, Kurz K. Cross generational and transactional sexual relations in Sub Saharan Africa: prevalence and implications for negotiating safer sexual practices. Washington, DC, USA: International Centre for Research on Women and Population Services International; 2002. Available from: https://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Cross-generational-and-Transactional-Sexual-Relations-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa-Prevalence-of-Behavior-and-Implications-for-Negotiating-Safer-Sexual-Practices.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2015. | ||

Campbell C. Selling sex in the time of AIDS: the psycho-social context of condom use by sex workers on a Southern African mine. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(4):479–494. | ||

Mitchell K, Wellings K, Elam G, Erens B, Fenton K, Johnson A. How can we facilitate reliable reporting in surveys of sexual behaviour? Evidence from qualitative research. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9(5):519–531. | ||

Plummer ML, Ross DA, Wight D, et al. “A bit more truthful”: the validity of adolescent sexual behaviour data collected in rural northern Tanzania using five methods. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80 Suppl 2:ii49–ii56. | ||

Kesby M. Participatory diagramming as a means to improve communication about sex in rural Zimbabwe: a pilot study. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(12):1723–1741. | ||

Mhloyi M. Perceptions on communication and sexuality in marriage in Zimbabwe. Women Ther. 1990;10(3):61–74. | ||

Gregson S, Zhuwau T, Anderson RM, Chandiwana SK. Apostles and Zionists: the influence of religion on demographic change in rural Zimbabwe. Popul Stud (Camb). 1999;53(2):179–193. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.