Back to Journals » Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics » Volume 9

Conceptualizing age-appropriate care for teenagers and young adults with cancer: a qualitative mixed-methods study

Authors Lea S , Taylor RM , Martins A, Fern LA, Whelan JS , Gibson F

Received 1 August 2018

Accepted for publication 23 August 2018

Published 24 October 2018 Volume 2018:9 Pages 149—166

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S182176

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Alastair Sutcliffe

Video abstract presented by Sarah Lea

Views: 140

Sarah Lea,1 Rachel M Taylor,1 Ana Martins,1 Lorna A Fern,1 Jeremy S Whelan,1 Faith Gibson2,3

1Cancer Division, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK; 2School of Health Sciences, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK; 3Centre for Outcomes and Experience Research in Children’s Health, Illness and Disability, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Purpose: Teenage and young adult cancer care in England is centralized around 13 principal treatment centers, alongside linked “designated” hospitals, following recommendations that this population should have access to age-appropriate care. The term age-appropriate care has not yet been defined; it is however the explicit term used when communicating the nature of specialist care. The aim of this study was to develop an evidence-based, contextually relevant and operational model defining age-appropriate care for teenagers and young adults with cancer.

Materials and methods: A mixed-methods study was conducted comprising 1) semi-structured interview data from young people with cancer and health care professionals involved in their care; 2) an integrative literature review to identify the current understanding and use of the term age-appropriate care; 3) synthesis of both sets of data to form a conceptual model of age-appropriate care. A combination of qualitative content, thematic and framework analysis techniques was used to analyze and integrate data.

Results: Analysis and synthesis across data sources enabled identification of seven core components of age-appropriate care, which were presented as a conceptual model: best treatment; health care professional knowledge; communication, interactions and relationships; recognizing individuality; empowering young people; promoting normality; and the environment. Subthemes emerged which included healthcare professionals clinical and holistic expertise, and the environment comprising both physical and social elements.

Conclusion: The proposed model, necessarily constructed from multiple components, presents an evidence-based comprehensive structure for understanding the nature of age-appropriate care. It will be useful for clinicians, health service managers and researchers who are designing, implementing and evaluating interventions that might contribute to the provision of age-appropriate care. While the individual elements of age-appropriate care can exist independently or in part, age-appropriate care is optimal when all seven elements are present and could be applied to the care of young people with long-term conditions other than cancer.

Keywords: age-appropriate care, teenagers, adolescents, young adults, young people, cancer, health care delivery, BRIGHTLIGHT

Introduction

There is increasing recognition of the need for health care for young people to be different from that received by children and adults.1 The term age-appropriate care is one term used to explain what these services should consist of. In England, teenage and young adult (TYA) cancer care is centralized around 13 Principal Treatment Centers, alongside linked “designated” hospitals. This service configuration was directed by the Improving Outcomes Guidance (IOG) for children and young people, published by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE).2 This document introduced a set of key recommendations for children and young people (aged 0–24 years), diagnosed with cancer, in direct response to consistent practice and policy requests to recognize the distinct needs of this population.

Young people have been described in the past as being “on the margins of medical care”.3 A lack of flexibility of services, insufficient training for health care professionals, poor communication and irregular and variable implementation of guidelines are some of the reasons reported as why the health needs of young people have historically not been met.3 Despite a strong focus in the UK National Health Service (NHS) to promote patient-centered care and to improve integration and transition between health services,4 services continue to be rigidly segregated by chronological age. Health services are pragmatically divided to serve specific age groups of the population: the new born and those born prematurely, children, adults and older people. Emerging in the past 10 years, there has been a promising trend toward separate services for young people in response to young people consistently calling for dedicated hospital services for their age group.5

Policy in the UK has played an important role in responding to such calls for changes to services. First published in 20055 and with three further editions in 2007, 2011 and 2017,6–8 the “You’re Welcome” quality criteria outlined the standards against which a “young-person-friendly” health service is currently measured in England. These criteria set useful standards for service managers, clinicians, service developers and nonclinical leaders to improve health services for young people. These were the first national standards to be endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO).9 The quality criteria deliver helpful guidance based on local practice, alongside evidence of strategies that will improve young people’s experience of health care and health outcomes.8 Despite initiatives such as the WHO “Agenda for Change”,10 a global review of young-people-friendly health services reported a shortage of applicable evidence to support specialist young people’s services as very few services had been evaluated.11 The Association for Young People’s Health (AYPH) has suggested that the NHS should instigate conversations with UK youth organizations to evaluate services, listen to young people’s issues and ideas concerning health matters and take actions to improve services.12

The voluntary sector has also played a key role. Cancer was the frontrunner in developing services specifically for young people. The UK was one of the first countries to establish specialist services, with the formation of Teenage Cancer Trust in the early 1990s in response to service inequalities.13 Further policy has strengthened the case for dedicated units. The Calman–Hine report prompted the reconfiguration of cancer services in the UK,14 including those for children and young people. Dedicated promotion and research into the unique needs of teenagers and young adults with cancer,15–18 high-profile lobbying19 and efforts of key individuals who have worked hard to raise awareness of the health service requirements of this specific population20,21 have together led to the continued evolution of young people’s cancer services in the UK.

A lack of UK-based evidence of the appropriateness of health services delivering care to young people with cancer continues to be acknowledged.22 The recommendations in the IOG were based on considerable evidence, apart from data to underpin the recommendations specific to the TYA age group, reflective of the limited research conducted prior to 2005 within this population.23,24 Despite this shortage of evidence, the IOG recommended age-appropriate care and separate services for young people with cancer, as did the Cancer Reform Strategy25 and several more recent publications.26–30 Popular both nationally and internationally, the term age-appropriate care continues to be used and underlies the agreed philosophy of care for this population. For example, one of the workforce needs presented in the latest “Blueprint of Care”31 was for professionals working with young people with cancer to “know how to provide age-appropriate care”. Young people themselves also use the term age-appropriate, suggesting that definition and shared understanding have been somewhat taken for granted.

Further afield, the variation in European and International service configurations and policy in young people’s cancer, makes the development of a global and integrated evidence-base an ongoing challenge.32,33 Furthermore, there are differences in the extent to which cancer services really do meet the needs of this age group.34 This is compounded by the variation in the age range used when defining what is meant by a “teenager or young adult”, which has been described as “the age conundrum”.33 A recent international survey demonstrated differences in the age boundaries for young people’s cancer services within Europe: it highlighted that there should be flexibility in the lower and upper age boundaries to account for individuality of patients and circumstances.33 Even within the UK, variation exists and this variability may affect young people’s experiences of care.34 There is an increased understanding of the combination of legal, political and system-driven reasons that make setting explicit age parameters for young people’s cancer services highly difficult, and potentially unfeasible.33 The phrase age-appropriate care is applied across all young people’s cancer services, regardless of the discrete patient age configuration, and hence it warrants a more explicit and evidence-based description of what it actually means.

BRIGHTLIGHT is a program of research evaluating specialist cancer care for young people in England. Preliminary work has explored young people’s and professional’s priorities for a specialist cancer unit,35 conceptualized young people’s experience of cancer24,36 and mapped TYA cancer services in England.34 In the latter study, Vindrola-Padros et al34 reported broad, overarching components of age-appropriate care, which highlighted the need for further exploration and description within BRIGHTLIGHT. Within the BRIGHTLIGHT program, a case study was designed with the intended purpose “to refine the main components of care, to identify what age-appropriate care means”.34 This article is reporting on one element of that case study to conceptualize the term age-appropriate care.

Aim

We aimed to explore how age-appropriate care is currently defined in the UK to assist health care professionals, commissioners and those developing services for young people with cancer. We sought to understand how it is described and operationalized in policy documents and the literature and find out what it means to young people receiving cancer care and to health care professionals providing it.

Materials and methods

A mixed-methods study was conducted, synthesizing semi-structured interviews and an integrative literature review to identify and map the key components of age-appropriate care for young people with cancer (Figure 1). This follows an approach that has been used previously.24,37,38 The developing conceptual map was subject to regular critique by members of the BRIGHTLIGHT research team.

| Figure 1 Flowchart of the iterative approach used to develop the model. |

Data collection and analysis

Qualitative semi-structured interviews

Sample and setting

Data were collected by one researcher (SL) for the BRIGHTLIGHT case study from four TYA cancer networks of care, including 29 hospitals. Participants included a convenience sample of young people cared for in these hospitals and a purposive sample of health care professionals delivering that care, reflective of a range of the multidisciplinary team where possible.

Ethical approvals

Ethical approval was granted for the case study by an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 13/LO/1869), and the local study approval was obtained in the individual hospitals where patients and health care professionals were interviewed. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants; if interview participants were under the age of 16 years, both written informed consent of their legal guardians and written informed assent of the young person were acquired.

Data collection: case study

Data collection consisted of interviews with young cancer patients and health care professionals and focused ethnography within multiple cancer treatment settings, including shadowing health care professionals. Within the interviews, participants were asked to define age-appropriate care. If responses were vague, the researcher used probes until she was clearly able to record the interviewee’s interpretation of age-appropriate care. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were anonymized and stored on NHS encrypted computers.

Analysis

The transcripts were read through several times to get a sense of the whole interview. The specific passages of each interview in which the definition of age-appropriate care was discussed were extracted and collated into one text, comprising the unit of analysis. The extracted dataset was de-identified to ensure that researchers could not link data to individual participants or hospitals, therefore minimizing the chance of researcher bias.

Qualitative content analysis was conducted on the extracted interview text. Initially, the obvious, manifest content was highlighted and notes were made in the margins of the underlying, latent content of each interview excerpt. A conventional, data-driven, inductive approach was used to draw out codes and meaning units relating to the term age-appropriate care.39 The meaning units were then condensed and coded with a succinct word or phrase to clearly mark their meaning. The codes were then compared across the transcript excerpts to look for commonalities and differences, both within and across the two populations interviewed. To ensure rigor, a process of reflection and discussion was conducted with two researchers (RMT and FG) about the identified themes and subthemes. The finalized themes were used to construct a framework, which was used to analyze the literature.

Integrative literature review

An integrative literature review was conducted to offer a collective perspective.38 The question guiding the review was as follows: “What key concepts underpin the term ‘age-appropriate care’ for teenagers and young adults with cancer?” The term “care” included looking at treatment, facilities and environments, all of which are commonly described as age-appropriate in the literature.

The literature was searched systematically with the objective of finding published and unpublished research, reports, books and articles, specific to cancer, written in English and from the UK. The search period was from 1959 to 2017; from 1959 because this was when the Platt report40 was published, a document that is widely recognized as the first and seminal report concerning the need for distinct adolescent health services in the UK. . First, a comprehensive, computer-assisted search of electronic databases was conducted using specified search terms. Databases searched were as follows: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycInfo. The search terms used were as follows: Age-appropriate, Adoles*, Teen*, Youth, Young adult, Young people, Young person, Cancer, Oncol*, Neoplasm. Books and reports were identified by members of the core research team who had expert knowledge of UK-specific resources available. If books included non-UK authors, they were included if one of the authors/editors was UK based.

The “Find” tool was used to search electronic documents for the term age-appropriate. The words such as “appropriate” and “age” were also searched individually, which allowed for relevant phrases such as “age-specific” and “appropriate for adolescents” to be identified. Paragraphs of text surrounding the keywords were read to clarify relevance and meaning. If the literature was not available in an electronic format, the text was reviewed by one researcher (SL) for these words and again any sections found were read thoroughly to assess relevance. Data were extracted and tabulated using a framework developed from the interview data with the addition of author, year of publication and type of publication. This framework-based approach allowed synthesis of different data sources: research, literature and policy.41 An additional “other” column in the framework allowed for documentation of new codes and meaning units. These were then included in the synthesis and generation of the final seven themes that illustrated what is meant by age-appropriate care.

Consultation with the BRIGHTLIGHT research team

The conceptual model was enhanced through an iterative consultation process with members of the BRIGHTLIGHT research team. The synthesis, identification of themes and construction of the model were presented to the team, who critiqued the interpretation of data and direction of relationships. This interactive team approach enabled the content and clarity of the conceptual model to be refined to ensure that the model remained true not only to the evidence but also contextually relevant to clinical services.

Results

The findings of each data source are summarized, followed by a presentation of the key themes.

Interviews with young people and health care professionals

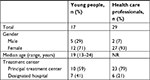

Forty-six out of 70 participants responded to the question about the definition of age-appropriate care in their semi-structured interview. This included 17 young people and 29 health care professionals. Participants were from a range of locations across the networks of care, both in TYA principal treatment centers or in designated hospitals – these hospitals are linked to the principal treatment center and have been evaluated as providing some, but not all aspects of, care described as “specialist” (Table 1).

| Table 1 Characteristics of study participants (n=46) Abbreviation: NR, not recorded. |

Integrative literature review

The process of the literature search, exclusion, inclusion and the yield is shown in Figure 2. A total of 150 documents were retrieved: 106 documents were excluded after title scanning and a further 14 were excluded after being read for relevance and scanned for the words such as age-appropriate. Reasons for exclusion included the following: irrelevant to the aim of the study, duplicated citations and studies that were not UK based. A total of 30 article s were included in the review: nine research studies,23,24,34,35,42–46 six policy documents,2,25–27,29,47 three service guidelines,30,31,48 one service evaluation,49 three books50–52 and eight commentary articles18,53–59 (Table S1).

| Figure 2 Flowchart of the literature search strategy and yield. Abbreviation: DOH, Department of Health; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. |

Synthesis of findings

Seven themes emerged from the synthesis of the interview and literature data as being fundamental to age-appropriate care are as follows: 1) Best treatment; 2) Health care professional knowledge; 3) Recognize individuality; 4) Communication, interactions and relationships; 5) Empowering young people; 6) Promote normality; 7) The environment.

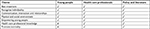

The weight of each theme varied across the three datasets, with five of the themes present in the interviews with young cancer patients and all seven of the themes evident in the health care professional interviews and reviewed literature (Table 2). A selection of supporting quotes from the three datasets is presented in Table 3, demonstrating their contribution to the development of the model of age-appropriate care.

| Table 2 Seven key themes and the datasets from which where they emerged |

Best treatment

Treatment emerged as a core component of age-appropriate care. It was described as the “essence” of age-appropriate care by health care professionals, who also recognized that receiving the best treatment possible would be a priority for young people, which was the case. Young people felt that good communication between health care professionals enabled treatment to be carried out safely.

Best practice treatment of young people’s cancer was discussed as an essential requirement of providing age-appropriate care in the literature.27,29,31,50,55 National guidelines urged increased development of clinical trials including teenagers and young adults.2,29 Access to clinical trials and participation in research was also recognized in the interviews with health care professionals as important to age-appropriate care. They also noticed how young people were often concerned about where they could receive the best treatment possible for their disease and would spend time researching their options.

Health care professional knowledge

Health care professionals’ knowledge was present in the health care professional interviews and literature. Two subthemes arose within this: clinical expertise and holistic expertise. Data described a need for “professionals who are experts”, which suggested an exceptionally high level of proficiency when working with this population. Both clinical and holistic expertise have previously been recognized as key competencies for staff working with young people with cancer.44,45

Health care professionals’ clinical expertise

Specialist young people’s cancer services provide an unrivaled collection of expertise.18,29,51,55 Encountering younger patients on a regular basis enhanced the health care professionals’ medical experience in diagnosing and treating patients of this age. Health care professionals discussed the need for knowledge of cancers and treatments specific to young people and associated clinical issues that were distinctive to this patient population, such as late effects.

Health care professionals’ holistic expertise

Building a solid understanding of the developmental, psychosocial and practical challenges of teenage and young adulthood was important to health care professionals, in addition to having a genuine passion to work with this age group. It was suggested that this could assist professionals in providing holistic care to their patients. Similarly, the literature recommended delivery of age-appropriate care required personnel with a particular interest in this age group. A need was emphasized for adequate psychological support for young people with cancer.31,53 Access to specialist staff confident and trained in recognizing psychological issues and providing psychological support was a vital part of age-appropriate care.25,50

Recent literature highlighted a drive to embed high-quality nursing care into specialist young people’s cancer care, needing continued effort to enhance the knowledge and competence of nurses who work with these patients in all services that care for young people with cancer.44,45,48 Educational programs need to facilitate professional’s progression from novice to expert.44

Communication, interactions and relationships

Building relationships with health care professionals was important to young people. They talked about having meaningful conversations with nurses, feeling comfortable with them and getting advice. Young people enjoyed getting to know the nurses caring for them as individuals and having genuine interactions. While in agreement with this, health care professionals also recognized that interacting with this age group could be complex. They suggested that building relationships with young people did not “happen overnight”. This mirrored previous findings that young people felt it important for professionals to ‘take their time’ and ‘get to know you’.34 It was emphasized in the Blueprint of Care that an age-appropriate approach involved obtaining a good understanding of patient’s interests and hobbies.31

Additionally, Vindrola-Padros et al34 found that “continuity of staff, familiar faces” facilitated continuity of care, which made young people feel safe and at ease. Communication between members of the multidisciplinary team looking after a young person led to coordinated care and joined-up working.26 Likewise, young people felt that age-appropriate care was “everybody knowing what’s going on” and expressed that everyone should be well informed.

Communication was recognized in the literature as an essential skill for professionals working with TYAs24,44,45 and should be sensitive, effective and timely.2,18 Young people and health care professionals were explicit that age-appropriate care required good communication, alongside honest interactions and the evolution of genuine relationships. Health care professionals discussed the different methods of communication that they could use and about approaching young people “at the right level”. Taylor et al’s35 highest ranked priority of the young people in their research was to have a unit where “we are treated like adults but we get the privileges and time that children do”. Young people in this study echoed this and wanted to be treated like adults, but to be recognized to have different needs to those of older adults.

Recognize individuality

There was agreement between health care professionals and young people that all care provided should be tailored to the individual patient’s needs. This concept was evident in the literature. A “one-size-fits-all approach” would not suffice as young people’s needs vary,54 but there were challenges of providing individualized services to young people and that “perceptions of ‘age appropriate’ vary according to life-stage commitments” strengthening the argument that “knowing patients” is central to provision of age-appropriate care.35

Young people appreciated the individuality of their personality, situation and disease. The NHS Quality Standards for Children and Young People’s Cancer 29 stated that services should consider every patient’s cancer as an individual case, further reinforcing the importance of recognizing individuality as a component of age-appropriate care.

Empowering young people

Young people felt that they should be kept informed of what was going on with their cancer and treatment, stating “at the end of the day it’s your body”. Young people felt empowered by being kept informed,35 and health care professionals are encouraged to provide the right resources and information, in the right way, at the right time, to empower young people.31 Subsequently, feeling empowered could encourage young people to participate in their own information seeking and decision-making,31,35 which can further increase feelings of empowerment.35 Health care professionals emphasized the importance of giving young people control and making them a “partner within their care”. An essential TYA health care professional competency was “to work in partnership with young people”.45 It was expressed how crucial empowerment could be to assist young people’s continued engagement with their treatment and this should involve giving patients’ choice.34,45

All three datasets advocated including young people in the design and development of cancer services for teenagers and young adults. Work has been carried out to ensure that specialist units are designed with the advice of young people, and this ongoing partnership needs to continue as it is highlighted in this study to underpin the delivery of age-appropriate care.

Promote normality

The literature and the health care professional interviews highlighted promoting normality as part of delivering age-appropriate care. Health care professionals felt it was their role to encourage young people to “stay on track” with aspects of their life such as education, which was also reflected in the literature.23,31 Encouraging interaction with peers and providing facilities and activities targeted toward young people were tools that health care professionals described as using to assist with the promotion of normality.

Environment

The environment as a component of age-appropriate care was discussed from two perspectives: the physical and the social environment.

Physical environment

The physical environment emerged as a crucial component. The IOG stated, “It is well documented that age-appropriate facilities are paramount”, which corresponded to the opinions of interviewees.2 Participants used phrases that signified importance when referring to the physical environments of care. Health care professionals said that the environment was “key”, “a massive issue” and “top of the list”, and likewise young people said that “the number one for me is the environment”. The literature commonly used the phrases such as age-appropriate environment, age-appropriate ward, or age-appropriate unit.23,26,31,48,51 While some literature provided details,31,54 the literature was noticeably vague as to what specifically constituted an age-appropriate environment.

Details of decor, structure, function and facilities of an age-appropriate environment were described in the interviews, as summarized in Table 4. In line with those listed in Table 4, Chapter 4 of the Blueprint of Care31 outlined several features of age-appropriate physical surroundings, such as flexible visiting times, flexible ward routine and bringing personal items into the hospital. A key factor for young people which recurred in the interviews was having a space to go away from their bed space. This was important to young people of all ages. Young people felt that they needed somewhere else to go, to be able to move away from their bed space and to have some freedom.59 This is one of the unique advantages of a specialist young person’s unit.

| Table 4 Description of an age-appropriate physical environment from the interviews |

The physical environment was important to all young people; however, there were some young people interviewed who had been cared for in adult services within designated hospitals. While not specialist, they felt that the physical environment they experienced provided everything they needed, which was to “feel at home and comfortable”. This resonated with the opinions of some health care professionals who viewed a specialist “all-singing, all-dancing” physical environment as the “icing on the cake”, rather than a core component of age-appropriate care.

Social environment

The importance of social interaction and unity among young people was a central theme in the interviews and literature. Young people experience significant social and personal development and literature advocated peer group support as a vital part of this.46,54 Health care professionals recognized that much of this development occurred in the context of peers. Three types of peer support emerged: support from other young people going through cancer treatment, support from existing peers and support from those living beyond cancer acting as role models. These are briefly discussed as follows: 1) Support from other young people going through cancer treatment: a positive, friendly and welcoming climate that promoted social interaction was important to young people.34 Young people described their environment of care to be like a “chemo youth club”, which portrayed a social environment of togetherness and solidarity between young people. Recreational activities were advocated in the literature, and these could encourage social interaction with peers, potentially with reduction in social isolation;31 2) Support from existing peers: young people talked about the advantages of having flexible visiting hours on the young person’s ward as it gave more opportunity for friends to visit compared to when they were staying on an adult ward. This indicated that flexibility in the way that the environment was used contributed to age-appropriate care, which was supported in the literature;48,56 3) Support from those living beyond cancer acting as role models: young people gained support and comfort from young people who had been through and were beyond treatment. These peers acted as role models to young people who were going through their cancer treatment. Contact with cancer survivors following diagnosis was an important source of emotional support and part of an age-appropriate social environment of care.24

Exploring connections within the model of age-appropriate care

The seven themes are represented as a conceptual model of age-appropriate care (Figure 3), which illustrates our primary finding that age-appropriate care is indeed complex. The multiple facets, connections and interactions in the model are discussed in more detail. Relationships occurred between health care professional expertise and several other elements of age-appropriate care. A core part of health care professional holistic expertise is to recognize the individuality and uniqueness of the young people they look after. Sensitivity to a young person’s individuality will assist health care professionals to interact with young people in a way they feel comfortable with and to communicate the right information, in the right way and at the right time. This will help health care professionals to develop relationships that will benefit young people as they go through their cancer treatment.

| Figure 3 A conceptual model of age-appropriate care. |

Furthermore, a relationship exists between effective communication, information sharing and patient empowerment. The phrase “no decision without me” was mentioned by a health care professional when discussing the importance of young people being involved in their care; a reference to the NHS initiative for patient-centered care with the strapline: “No decision about me, without me”.60 Giving autonomy to empower young people was highlighted alongside the importance of recognizing their individuality. When health care professionals understand young people’s holistic needs, their life stage and commitments, they can consider how best to minimize the disruption that cancer treatment has on these other aspects of a young person’s life. One of the strategies presented in the Blueprint of Care was to encourage personalization of young patient’s bed spaces through having fittings such as notice boards for photographs and cards, to help create a more personal space.31 This allows young people to establish their individuality as well as promoting normality.

A noteworthy relationship linked young people’s physical and social environments as part of what makes age-appropriate care. An age-appropriate environment has been described as an environment in which young people can connect.54 Social interaction between young people thrives with a physical environment that has a separate space dedicated for socializing, whether with fellow patients or with existing friends and family.34 While socialization and peer support can occur without this, the provision of a separate space creates a dedicated place in which the social environment can grow.

A suitable physical environment was one factor found to assist in creating a social environment for young people with cancer. In order for a social environment to flourish, opportunities for socialization and peer support need to be encouraged, or even orchestrated, by professionals caring for young people. Generating a social environment where young people are together, friendships develop and peer support occurs, was recognized to be more challenging without the platform of an appropriate physical environment. The physical and social environments together provide an environment that is a central facilitator of providing age-appropriate care for young people with cancer.

Discussion

This study is unique as it harnesses what we can learn from existing literature on age-appropriate care and also integrates empirical evidence from health care professionals and young people to build a conceptual model. There was consistency across data in five of the seven themes that emerged: best treatment, recognizing individuality, communication, empowering young people and the environment. Two further themes, health care professional knowledge and promoting normality, were presented in both literature and health care professional data. The parity between the empirical findings and the examination of the literature in this study validates existing understanding of the terminology.

It has been recognized that caring for young people with cancer is often complex.32 Age-appropriate care is multifaceted; it should not be oversimplified with a straightforward definition. The components of the model have been carefully assembled to highlight how they are reliant on one another to optimize care. The concept has multiple layers and dimensions, which interlink and intertwine. While the individual elements of age-appropriate care can exist independently, age-appropriate care is optimized when all of the elements are present.

The environment of care is a focal part of the conceptual model presented; both the physical and the social environments contribute to young people’s experience of age-appropriate care. This substantiates our preceding work, where “age-appropriate activities” and an environment that “feels like home” were two main components of specialist TYA care.34 We propose that the specialist physical environment promotes feelings of normality for young people, which supports previous research suggesting that a flexible health care environment and relationships with peers are important to achieve a sense of normalcy.34,61

There were some health care professionals who suggested that the “all-singing, all-dancing TYA unit” is a contributing component of age-appropriate care but not essential, rather the “icing on the cake”. This reinforces that the model of age-appropriate care we are presenting needs to be viewed in its entirety, with age-appropriate care being far more than simply the provision of a specialist environment. This is in line with the definition of specialist TYA cancer units provided by Taylor et al,35 where dedicated units are introduced and underpinned by expertise and philosophy of care.

Recognizing individuality was identified as fundamental to age-appropriate care. International literature has advocated for professionals to recognize the developmental stages that young people undergo as part of understanding a patient’s individual needs.61,62 For this reason, “developmentally appropriate” care has been proposed as alternative terminology.61 We would argue that understanding young people’s developmental needs is a part of understanding young people’s holistic needs, which is presented in the conceptual model. This has been recognized as a major challenge for health services because young people have a range of needs based on their personal circumstances.10 The model addresses these issues, recognizing the individuality of young people, using effective and honest communication and empowering young people are all strategies which we suggest should be employed in the provision of age-appropriate care.

In this study, some professionals did not consider the term age-appropriate a true reflection of the care that they provided and that patient-appropriate would be more suitable. In line with our study findings, there is literature advocating for individualized patient care for young people with cancer29,31,61,62 and one could argue for a change in terminology. Kitson et al63 explored patient-centered care within medical and nursing literature and policy. They presented patient involvement, the context of care and the relationship between the patient and the health care professional to be the three major themes of patient-appropriate care. These coincide closely with the findings of our study. However, we found many more facets to age-appropriate care than these three aspects. We therefore argue that the phrase age-appropriate care should be cherished and preserved. This study has shown that it has value, meaning, currency and mileage within health services both in the UK and internationally. This extends beyond young people with cancer and could be adopted by those caring for young people with other long-term conditions.

Alongside age-appropriate, the term young-people-friendly is becoming more and more frequently used to describe health services for young people.3,8,28 In the past decade, there has been increased interest in young people’s health care which has led to services being better tailored to the needs of young people.64 Communication that was skillfully orchestrated at the right time, in the right way between professionals and young people, as well as between professionals of the multidisciplinary team, was found to be core in the model. Moreover, the interactions and relationships built were shown to be of major importance to young people’s experiences of care. It has been suggested that inadequate training for health care professionals and poor communication skills are contributing factors to young people having poor health care experiences.3 In concordance with this, our model indicates where staff training and education around these issues should be addressed.

Our findings could be applied to other areas of young people’s health care. There is a national drive in the UK to enhance the health services that we provide for young people, with an increasing recognition of how their needs differ from those of children and older adults.3,7,8 Commissioners, service developers and health care providers should work together to advance and enhance such services. However, to do so, there needs to be clearer definition of what these should be. The “You’re Welcome” quality criteria depict the standards against which a young-person-friendly health service is currently measured against in England.3 Our conceptual model of age-appropriate care overlaps with these standards, which are currently being piloted in England.8 In comparison, there is parity between the “You’re welcome” themes and the themes we found in the present study: staff skills and training; involving young people in their care and in the delivery and review of services; and communication and linking with other services were key concepts in both pieces of work. This enhances the strength of our argument that this conceptual model of age-appropriate care has application beyond cancer services.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is that it brought the views of health care professionals and young people, together with existing literature, to present a structured model of age-appropriate care for young people with cancer. However, some limitations need to be acknowledged. The specific dynamics, contexts and models of services that exist across the country and the world vary. There is considerable global variation in the age that young people can access specialist cancer services. For example, in North America, services for young people extend to 40 years of age, whereas in Australia they extend until 25 years and in the UK until 24 years.32 A further limitation of the study was that the interviews were conducted only in England: the BRIGHTLIGHT study is a national evaluation of young people’s cancer care in England. However, there is also variation within the UK as to the age at which young people are accepted into a specialist TYA service. Depending on the geographical area, it could be at 13, 15, 16 or 19 years that a specialist age-appropriate unit becomes accessible.34 While this makes it more complicated to delineate a worldwide definition of age-appropriate care, the differences and variations in models and ages served by specialist care in the UK make the findings of this study somewhat more generalizable. Due to extensive international variation, international literature was excluded from the literature review to increase the validity of this as an operational conceptual model to the UK approach to age-appropriate care.

Despite these limitations, our study included the views of young people between 13 and 24 years of age, which overlap to some extent with all international definitions of young person. We therefore believe that our model of age-appropriate care can apply to health care services outside of the UK and interpretation of the interactions between the components of the model can support not only young people’s health care services in Western countries but also those in developing countries where there are fewer resources available.

We recognize that variations in service structure and function could affect the implementation of this model in practice. Yet, despite these limitations, we are confident that the model presents an evidence-based and comprehensive structure for understanding age-appropriate care. It has been acknowledged that caring for young people with cancer is often complex.32 Age-appropriate care cannot be oversimplified with the use of a single term: this is clearly illustrated in the complexity of the model. We can now be more confident in knowing exactly what we mean when we use the term age-appropriate care and therefore how we might identify and measure it.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation of both patient and professional understanding of age-appropriate care for young people with cancer together with an integrative review of literature. The study provides important findings that are intended to impact future policy and practice in young people’s cancer care. While the individual elements of age-appropriate care can exist independently or in part, age-appropriate care is optimal when the seven elements are all present. It will be important to consider how all of the elements presented in the model of age-appropriate care could be facilitated when designing and delivering young people’s cancer services. Where current services do not “tick all of the boxes” in terms of delivering age-appropriate care, we hope this model will drive services to evaluate, recognize and address areas of deficit. Opponents of the provision of specialist age-appropriate care will question whether there is any benefit and impact on young people’s outcomes from receiving age-appropriate care, as described in this study. The results of the BRIGHTLIGHT cohort study are anticipated in 2018 and will indicate whether specialist TYA cancer services add value. These results may be applied to the care of young people with other long-term conditions, not just those with cancer, thus advocating further for the unique needs of the population of teenagers and young adults.

Acknowledgments

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (grant reference number: RP-PG-1209–10013). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. LAF was funded by Teenage Cancer Trust, and AM was funded by Sarcoma, UK. None of the funding bodies have been involved with study concept, design or decision to submit the manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

This manuscript has not been published or submitted to any other journals, but it has been presented orally at the joint BRIGHTLIGHT and Teenage and Young Adults with Cancer (TYAC) Conference in Leeds, UK, in July 2017 and as a poster presentation in the Adolescent and Young Adult Global Cancer Congress in Atlanta, USA, in December 2017. Neither of these presentations are publicly available. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Farre A, Wood V, Rapley T, Parr JR, Reape D, Mcdonagh JE. Developmentally appropriate healthcare for young people: a scoping study. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(2):144-51–151. | ||

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People with Cancer. London: Department of Health; 2005. | ||

Royal College of Physicians. On the Margins of Medical Care. Why Young Adults and Adolescents Need Better Healthcare. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2015. | ||

Seale B. Patients as Partners; 2016. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Patients_as_partners.pdf. Published June 2016. Accessed March 2017. | ||

Department of Health. You’re Welcome: Quality Criteria for Young People Friendly Health Services. London: Department of Health; 2005. | ||

Department of Health. You’re Welcome: Quality Criteria for Young People Friendly Health Services. London: Department of Health; 2007. | ||

Department of Health. You’re Welcome – Quality Criteria for Young People Friendly Health Services. London: Department of Health; 2011. | ||

Public Health England, NHS England and the Department of Health. You’re Welcome Pilot 2017 – Refreshed Standards for Piloting. London: Public Health England, NHS England and the Department of Health; 2017. | ||

Hargreaves DS, Mcdonagh JE, Viner RM. Validation of You’re Welcome quality criteria for adolescent health services using data from national inpatient surveys in England. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(1):50–57.e1. | ||

World Health Organization. Adolescent Friendly Health Services: An Agenda for Change. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. | ||

Tylee A, Haller DM, Graham T, Churchill R, Sanci LA. Youth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done? Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1565–1573. | ||

Hagell A, Coleman J, Brooks F. Key Data on Adolescence 2015. 10th ed. London: Association of Young People’s Health; 2015. | ||

Whiteson M. The Teenage Cancer Trust--advocating a model for teenage cancer services. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(18):2688–2693. | ||

Department of Health. A Policy Framework for Commissioning Cancer Services: A Report by the Expert Advisory Group on Cancer to the Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales. London: Department of Health; 1995. | ||

Selby P, Bailey C. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. London: BMJ Publishing; 1996. | ||

Mulhall A, Kelly D, Pearce S. A qualitative evaluation of an adolescent cancer unit. Eur J Cancer Care. 2004;13(1):16–22. | ||

Hollis R, Morgan S. The adolescent with cancer--at the edge of no-man’s land. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2(1):43–48. | ||

Whelan J. Where should teenagers with cancer be treated? Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(18):2573–2578. | ||

Teenage Cancer Trust [webpage on the Internet]. Teenage Cancer Trust- What we do. Available from: https://www.teenagecancertrust.org/about-us/what-we-do. Updated in 2018. Accessed May 22, 2018. | ||

Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer [homepage on the Internet]. Teenagers and Young Adults With Cancer – What we do. Available from: https://www.tyac.org.uk/. Updated in 2018. Accessed May 26, 2018. | ||

Barr RD, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults: A Narrative Review of the Current Status and a View of the Future. JAMA Paediatr. 2016;170(5):495–501. | ||

Ferrari A, Albritton K, Osborn M, et al. Access and models of care. In: Bleyer A, Barr R, Ries L, Whelan J, Ferrari A, editors. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016:509–548. | ||

Marris S, Morgan S, Stark D. ‘Listening to Patients’: what is the value of age-appropriate care to teenagers and young adults with cancer? Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20(2):145–151. | ||

Fern LA, Taylor RM, Whelan J, et al. The art of age-appropriate care: reflecting on a conceptual model of the cancer experience for teenagers and young adults. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(5):E27–E38. | ||

Department of Health. Cancer Reform Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2007. | ||

National Cancer Peer Review Team – National Cancer Action Team. Manual for Cancer Services: Teenagers and Young Adult Measures. London: NHS; 2011. | ||

NHS England. 2013/14 NHS Standard Contract for Cancer: Teenagers and Young Adults. London: NHS; 2013. | ||

England NHS. Manual for Cancer Services: Teenage and Young Adults Measures. London: NHS; 2014. | ||

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [webpage on the Internet]. Cancer Services for Children and Young People Quality Standard 55. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs55. Published February 2014. Accessed April 21, 2018. | ||

Smith S, Case L, Waterhouse K. A Blueprint of Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2012. | ||

Smith S, Mooney S, Cable M, Taylor R. The Blueprint of Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer. 2nd ed. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2016. | ||

Ferrari A, Thomas D, Franklin AR, et al. Starting an adolescent and young adult program: some success stories and some obstacles to overcome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4850–4857. | ||

Pini S, Gardner P, Hugh-Jones S. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on the education engagement of teenagers - patient and staff perspective. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(3):317–323. | ||

Vindrola-Padros C, Taylor RM, Lea S, et al. Mapping Adolescent Cancer Services: How Do Young People, Their Families, and Staff Describe Specialized Cancer Care in England? Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(5):358–366. | ||

Taylor RM, Fern L, Whelan J, et al. “Your Place or Mine?” Priorities for a Specialist Teenage and Young Adult (TYA) Cancer Unit: Disparity Between TYA and Professional Perceptions. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1(3):145–151. | ||

Taylor RM, Pearce S, Gibson F, Fern L, Whelan J. Developing a conceptual model of teenage and young adult experiences of cancer through meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(6):832–846. | ||

Tsangaris E, Johnson J, Taylor R, et al. Identifying the supportive care needs of adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer: a qualitative analysis and systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):947–959. | ||

Bravo P, Edwards A, Barr PJ, Scholl I, Elwyn G, McAllister M; Cochrane Healthcare Quality Research Group, Cardiff University. Conceptualising patient empowerment: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):252. | ||

Kondracki NL, Wellman NS, Amundson DR. Content analysis: review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34(4):224–230. | ||

Platt H. The Welfare of Children in Hospital, Platt Report. London: HMSO; 1959. | ||

Dixon-Woods M. Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies. BMC Med. 2011;9:39. | ||

Wilkinson J. Young people with cancer - how should their care be organized? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2003;12(1):65–70. | ||

Kelly D, Pearce S, Mulhall A. ‘Being in the same boat’: ethnographic insights into an adolescent cancer unit. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(8):847–857. | ||

Gibson F, Fern L, Whelan J, et al. A scoping exercise of favourable characteristics of professionals working in teenage and young adult cancer care: ‘thinking outside of the box’. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2012;21(3):330–339. | ||

Taylor RM, Feltbower RG, Aslam N, Raine R, Whelan JS, Gibson F. Modified international e-Delphi survey to define healthcare professional competencies for working with teenagers and young adults with cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011361. | ||

Moran O, Valiallah N. An Evaluation of Age-Appropriate Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer in Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust, Paying Particular Attention to In-Patient Physical Environment and Peer Support. [Masters]. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2013. | ||

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People With Cancer: The Evidence Review. London: Department of Health; 2005. | ||

Smith S, Cable M, Morgan S, Siddall J, Chamley C. Competencies: Caring for Teenagers and Young Adults With Cancer: A Competence and Career Framework for Nursing. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2014. | ||

Wright C. Evaluation of the Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Service, Leeds – Comprehensive Report. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2012. | ||

Bleyer A, Barr R. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. | ||

Eden T, Barr R, Bleyer A, Whiteson M. Cancer and the Adolescent. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. | ||

Kelly D, Gibson F, editors. Cancer Care for Adolescents and Young Adults. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. | ||

Geehan S. The benefits and drawbacks of treatment in a specialist Teenage Unit--a patient’s perspective. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(18):2681–2683. | ||

Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4825–4830. | ||

Brierley R, Holmes D, Ceschia A, Jouret J. Teenage Cancer Trust: pursuing equality. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):455–458. | ||

Rajani S, Young AJ, Mcgoldrick DA, Pearce DL, Sharaf SM. The International Charter of Rights for Young People with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1(1):49–52. | ||

Blakemore S. Age-appropriate care is vital: nurses given guidance on meeting specific needs of teenagers and young adults. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2012;11(6):6–7. | ||

Carr R, Whiteson M, Edwards M, Morgan S. Young adult cancer services in the UK: the journey to a national network. Clin Med. 2013;13(3):258–262. | ||

Gibson F. What is it really like to be a young person, in our hospital, at this moment? Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(2):86–87. | ||

Department of Health. Liberating the NHS: No Decision About me, Without me. London: Department of Health; 2012. | ||

D’Agostino NM, Penney A, Zebrack B. Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117(10 Suppl):2329–2334. | ||

Zebrack BJ, Psychological ZB. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(10 Suppl):2289–2294. | ||

Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(1):4–15. | ||

Ambresin AE, Bennett K, Patton GC, Sanci LA, Sawyer SM. Assessment of youth-friendly health care: a systematic review of indicators drawn from young people’s perspectives. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(6):670–681. |

Supplementary materials

| Table S1 Details of articles included in the review Abbreviation: NHS, National Health Service. |

References

Gibson F. Adolescents with cancer: is it the location or philosophy of care which matters? Cancer Nurs. 1997;1(4):159. | ||

Geehan S. The benefits and drawbacks of treatment in a specialist Teenage Unit--a patient’s perspective. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(18):2681–2683. | ||

Whelan J. Where should teenagers with cancer be treated? Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(18):2573–2578. | ||

Wilkinson J. Young people with cancer - how should their care be organized? Eur J Cancer Care (Eng). 2003;12(1):65–70. | ||

Kelly D, Pearce S, Mulhall A. ‘Being in the same boat’: ethnographic insights into an adolescent cancer unit. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41(8):847–857. | ||

Eden T, Barr R, Bleyer A, Whiteson M. Cancer and the Adolescent. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. | ||

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People with Cancer. London: Department of Health; 2005. | ||

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People With Cancer: The Evidence Review. London: Department of Health; 2005. | ||

Department of Health. Cancer Reform Strategy. London: Department of Health; 2007. | ||

Brierley R, Holmes D, Ceschia A, Jouret J. Teenage Cancer Trust: pursuing equality. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):455–458. | ||

Kelly D, Gibson F, editors. Cancer Care for Adolescents and Young Adults. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. | ||

Morgan S, Davies S, Palmer S, Plaster M. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll: caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(32):4825–4830. | ||

National Cancer Peer Review Team – National Cancer Action Team. Manual for Cancer Services: Teenagers and Young Adult Measures. London: NHS; 2011. | ||

Marris S, Morgan S, Stark D. ‘Listening to Patients’: what is the value of age-appropriate care to teenagers and young adults with cancer? Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20(2):145–151. | ||

Rajani S, Young AJ, Mcgoldrick DA, Pearce DL, Sharaf SM. The International Charter of Rights for Young People with Cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1(1):49–52. | ||

Taylor RM, Fern L, Whelan J, et al. “Your Place or Mine?” Priorities for a Specialist Teenage and Young Adult (TYA) Cancer Unit: Disparity Between TYA and Professional Perceptions. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2011;1(3):145–151. | ||

Blakemore S. Age-appropriate care is vital: nurses given guidance on meeting specific needs of teenagers and young adults. Cancer Nurs Pract. 2012;11(6):6–7. | ||

Gibson F, Fern L, Whelan J, et al. A scoping exercise of favourable characteristics of professionals working in teenage and young adult cancer care: ‘thinking outside of the box’. Eur J Cancer Care (Eng). 2012;21(3):330–339. | ||

Smith S, Case L, Waterhouse K. A Blueprint of Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2012. | ||

Wright C. Evaluation of the Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Service, Leeds – Comprehensive Report. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2012. | ||

Carr R, Whiteson M, Edwards M, Morgan S. Young adult cancer services in the UK: the journey to a national network. Clin Med. 2013;13(3):258–262. | ||

Fern LA, Taylor RM, Whelan J, et al. The art of age-appropriate care: reflecting on a conceptual model of the cancer experience for teenagers and young adults. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(5):E27–E38. | ||

Moran O, Valiallah N. An Evaluation of Age-Appropriate Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer in Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust, Paying Particular Attention to In-Patient Physical Environment and Peer Support. [master’s thesis]. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2013. | ||

NHS England. 2013/14 NHS Standard Contract for Cancer: Teenagers and Young Adults. London: NHS; 2013. | ||

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [webpage on the Internet]. Cancer Services for Children and Young People Quality Standard 55. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs55. Published February 2014. Accessed April 21, 2018. | ||

Smith S, Cable M, Morgan S, Siddall J, Chamley C. Competencies: Caring for Teenagers and Young Adults With Cancer: A Competence and Career Framework for Nursing. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2014. | ||

Vindrola-Padros C, Taylor RM, Lea S, et al. Mapping Adolescent Cancer Services: How Do Young People, Their Families, and Staff Describe Specialized Cancer Care in England? Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(5):358–366. | ||

Smith S, Mooney S, Cable M, Taylor R. The Blueprint of Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer. 2nd ed. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2016. | ||

Taylor RM, Feltbower RG, Aslam N, Raine R, Whelan JS, Gibson F. Modified international e-Delphi survey to define healthcare professional competencies for working with teenagers and young adults with cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011361. | ||

Bleyer A, Barr R. Cancer in Adolescents and Young Adults. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.