Back to Journals » Local and Regional Anesthesia » Volume 15

Comparison Between Ultrasound-guided Caudal Analgesia versus Peripheral Nerve Blocks for Lower Limb Surgeries in Pediatrics: A Randomized Controlled Prospective Study

Authors Mahrous RSS , Ahmed AAA , Ahmed AMM

Received 30 April 2022

Accepted for publication 18 August 2022

Published 12 September 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 77—86

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/LRA.S372903

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Stefan Wirz

Rabab SS Mahrous,1 Amin AA Ahmed,2 Aly Mahmoud Moustafa Ahmed1

1Department of Anaesthesia and Surgical Intensive Care Alexandria University Alexandria Egypt; 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology Alexandria University Alexandria Egypt

Correspondence: Rabab SS Mahrous, Department of Anaesthesia and Surgical Intensive Care Faculty of Medicine Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt, Tel +201223497339, Email [email protected]

Background and Aim: Ultrasound (US) guided regional analgesia is a safe and effective method in providing perioperative analgesia in pediatrics with a high success rate rapid onset and fewer side effects. The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of US-guided caudal block versus US-guided peripheral nerve blocks (femoral and sciatic nerve blocks) in providing perioperative analgesia in pediatrics undergoing unilateral lower limb surgery.

Methods: Children aged 1– 12 years scheduled for unilateral lower limb surgery during the period from January 2020 to December 2021 were randomly allocated into two groups. Group C where pediatrics received US-guided caudal block, while in group P, pediatrics received US-guided femoral and sciatic nerve blocks after the induction of general anesthesia (GA). The primary aim was to compare the postoperative pain (evaluated by the COMFORT pain score) between the two groups. Secondary aims were to compare perioperative opioids used parents’ satisfaction and occurrence of side effects.

Results: Pediatrics who underwent unilateral lower limb surgeries were allocated into two groups (group C and group P). There was no significant difference between patients’ baseline characteristics and the postoperative pain score at 2, 4, 16, and 20 h.’ However there was a statistical significance at 6, 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively, frequency of analgesia as well as the total postoperative dose of opiates (nalbuphine). Time to first analgesic (nalbuphine) requirement was significantly less in group C with a mean of (9.6± 2.9 h) than in group P with a mean of (15.1± 3.5 h). Parents of children in group P were more satisfied than those in group C with no recorded complications for both techniques.

Conclusion: US-guided lower limb peripheral nerve block is a simple and safe method to provide adequate and more prolonged analgesia compared to US-guided caudal block for lower limb surgeries in pediatrics.

Keywords: caudal, analgesia, peripheral nerve, block, lower limb surgeries, pediatrics

Introduction

Regional analgesia (RA) in children has gained popularity worldwide lately; there is good evidence that RA provides good-quality pain relief, reduced opioid consumption, reduced incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting and reduced incidence of respiratory complications. RA is an important contributor of multimodal analgesia to improve patients’ health-care experience and reduce hospital length of stays.1

Pediatric RA is safe in children with no reported cases of permanent neurologic damage and the rates of transient neurologic deficit and local anesthesia toxicity were low as concluded by The Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (PRAN) database; The most recent analysis of these data includes a large data set with more than 100,000 regional blocks including both peripheral and neuraxial blocks.2

Caudal analgesia (CA) is one of the most popular regional blocks in infants and young children. CA is safe in infants and children even when given under general anesthesia especially when US is being used. However CA is an epidural neuraxial analgesia resulting in various effects including; bilateral sensory and motor blockade which limits ambulation immediately after surgery urinary retention, which may necessitate the need for catheterization and its potential adverse effects and sympathetic blockade and its associated hemodynamic effects including hypotension.3

Anatomical changes due to aging increase the difficulty in providing CA in older children. The increase in the lower back and sacral subcutaneous fat may obscure bony landmarks and closure of the sacral hiatus by calcification of the sacrococcygeal ligament may make needle placement more challenging.4

US adds extra safety to CA, the caudal area is not yet ossified in pediatric age and it can be visualized by the guidance of ultrasound. Abnormalities of the sacral formation such as sacral dysgenesis can also be detected using ultrasound scanning prior to block administration. Moreover a low-lying dural sac can be visualized with the use of real-time ultrasound. This helps to prevent unintentional dural puncture and the risk of total spinal anesthesia.4

The scope of RA in the pediatric anesthetic practice has been much improved in providing peripheral nerves and neuraxial blocks because of the advancement in the US and the image quality making the procedure easier safe with less dose of local anesthetics and fewer complications.5

The aim of this study was to compare the analgesic efficacy of two different regional analgesias: the ultrasound-guided caudal analgesia versus the peripheral nerve blocks for lower limb surgeries in pediatrics. The primary outcome of this study was to assess the duration of postoperative analgesia in addition to the total postoperative doses and frequency of opiates and parents satisfaction as secondary outcomes.

Methods

This prospective randomized study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University and the trial was registered prior to patient enrollment at Pan-African Clinical Trial Registry (PACTR202001664130773), date of registration 14 January 2020. The study was carried out in the period between January 2020 and December 2021. A written informed consent was obtained from the parents of each patient for agreement of participation in the study, (table S1). Children enrolled in the study aged 1–12 years American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I or II scheduled for unilateral lower limb surgeries at the university hospital. The exclusion criteria were the lack of parental consent, allergy to any local anesthetic, preexisting neuropathy (with sensory and/or motor deficits), cutaneous infection or wound close to the puncture point. Patients were optimized preoperatively.

On the day of surgery in the ward before leaving to the operating room (OR) children were premedicated with 0.5 mg/kg of midazolam orally. In the OR standard monitoring was attached including noninvasive blood pressure measurement, electrocardiograph pulse oximeter and end-tidal CO2. General anesthesia (GA) was induced in all children using sevoflurane (end-tidal fraction brought to 5%), after securing an intravenous cannula; intravenous 1 µg/kg fentanyl and propofol 2 mg/kg was given prior to the insertion of appropriate size of laryngeal mask airway (LMA), the child breathing was assisted until spontaneously breathing on a mixture of O2 (FiO2 1.0)/ sevoflurane (2 MAC) aiming to maintain end-tidal CO2 between 35 and 40 mmHg.

Children were then randomized into two groups (groups C and P) by a third party not involved in the study using a numbered closed envelope method to be subjected to the planned regional analgesic technique. All blocks were executed under the guidance of a 5–13 MHz linear ultrasound probe covered in a sterile sheath and attached to a Sonosite (M-Turbo; SonoSite Inc. Bothell WA USA) portable ultrasound machine. Preoperatively the maximum dose of levobupivacaine was calculated (2 mg/kg) so as not to exceed the dose during injection in either group.

Group C: in this group children received US-guided caudal analgesia (CA) after GA. The caudal block was performed by visualizing the sacral hiatus at the level of the sacral cornu after placing the probe transversely obtaining a short axis view, two hyperechoic lines appeared between the sacral cornu the superficial line is the sacrococcygeal ligament which was pierced by the needle 22-gauge echogenic non-stimulating 5-cm needle (Ultraplex; B. Braun Medical Bethlehem PA, USA) using the out-of-plane approach. After confirming the absence of any blood or cerebrospinal fluid in the aspiration the caudal mixture (1 mL/kg of 0.25% levobupivacaine a maximum volume of 20 mL will be used) was injected.6

Group P: in this group children received lower limb peripheral nerve blocks in the form of (US-guided femoral nerve block plus US-guided subgluteal sciatic nerve block).

For femoral nerve block (Figure 1A and B); the child was positioned supine, the probe was on the inguinal crease transversely to identify the femoral nerve artery and vein. The femoral nerve was identified lateral to the artery while the femoral vein was seen medial to the artery. An in-plane approach was used 22-gauge echogenic nonstimulating 5-cm needle (Ultraplex; B. Braun Medical) was introduced from lateral to medial towards the femoral nerve and the local anesthetic (0.3 mL/kg of 0.25% levobupivacaine) was injected circumferentially around the nerve.7

|

Figure 1 Femoral nerve block: (A) FN femoral nerve. FA femoral artery. FV femoral vein. (B) LA local anesthetic. |

For sciatic nerve block (Figure 2A and B); the subgluteal approach to the sciatic nerve was used. The child was put in the lateral decubitus position. The probe was placed at the gluteal crease between the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity the gluteus maximus muscle was identified; the sciatic nerve was situated deep to this muscle. An in-plane approach was used for needle guidance 22-gauge echogenic nonstimulating 5-cm needle (Ultraplex; B. Braun Medical). The local anesthetic (0.3 mL/kg of 0.25% levobupivacaine) was injected surrounding the nerve.7

|

Figure 2 Sciatic nerve block: (A) SN sciatic nerve. (B) LA local anesthetic. |

Intraoperatively anesthesia was maintained using an O2/Sevoflurane mixture, an increase of over 15% of the mean arterial pressure or heart rate as compared to preoperative reference values necessitated injection of 1 µg/kg of fentanyl intravenously.

After surgery the LMA was removed when the protective airway reflexes had recovered and the child regained consciousness after stopping the inhaled anesthetic. Intravenous paracetamol 15 mg/kg four times daily was systemically infused in all children for postoperative analgesia.

The followings were recorded by a third investigator blinded to the technique of regional analgesia given: postoperative pain scores evaluated by the COMFORT pain score8 every two hours for eight hours then every four hours thereafter until 24 h, the aim is to score less than 26 in order to consider adequate analgesia if analgesia was inadequate (0.15 mg/kg of nalbuphine was administered intravenously as rescue analgesia up to a maximum of four times a day), postoperative doses of opiates, parents satisfaction and side effects (technical block failure systemic toxicity to LAs nausea vomiting sedation local infections and hematoma owing to the puncture).

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS version 22. Data were described according to type. Qualitative variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Quantitative variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test at 5% test of significance. Data that were normally distributed were presented as mean and standard deviation, however median and interquartile range were used for not normally distributed data. Comparison between groups was done using the chi-squared test for qualitative variables Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test for quantitative variables. Analysis was done at 5% level of significance.

Results

One hundred and ninety-seven pediatric patients were assessed for eligibility. Fifteen patients were excluded either they did not meet the inclusion criteria or there was a lack of consent. The remaining 182 patients were randomly allocated to two groups 90 pediatrics were allocated to US-guided caudal intervention group (group C) and 92 pediatrics were allocated to US-guided femoral and sciatic intervention group (group P) (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Consort flow diagram. |

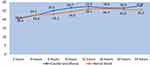

All patients underwent unilateral lower limb surgeries without any significant difference between patients’ baseline characteristics with regard to (Age, sex and weight) (Table 1) and also with regard the operative data (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the COMFORT pain score at two and four hours postoperatively as well as at 16 and 20 h postoperatively. However there was a statistically significant reduction at 6, 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively with a mean of (25.1±2.9, 26.7±2.8, 27.5±2.4, and 27.8±3.5, respectively) in group C. whereas in group P (23.1±1.3, 24.6±1.5, 26.1±2.4, and 27.8±3.5, respectively) with p-values of <0.001 <0.001 0.025 and <0.001, respectively (Table 3, Figure 4).

|

Table 1 Comparison Between the Two Groups Regarding Their Baseline Characteristics |

|

Table 2 Comparison Between the Two Methods of Anesthesia According to Their Operative Data |

|

Table 3 Comparison Between the Two Groups Regarding Postoperative Pain Score, the Frequency and Doses of Analgesics and Time to the First Analgesic |

|

Figure 4 Comparison of mean postoperative pain scores between the two methods of anesthesia. |

The frequency of analgesia as well as the total postoperative dose of opiates (nalbuphine) showed significant differences with p-values of <0.001. Median (IQR) for frequency of analgesia was 2.0 for group C, but it was 1.0 for group P. Whereas the median (IQR) for postoperative nalbuphine was 5 (2.6) mg in group C, but 3 (2) mg in group P. Time to first analgesic (nalbuphine) requirement was significantly less in group C with a mean of (9.6±2.9 h) than in group P with a mean of (15.1±3.5 h) (Table 3, Figure 4).

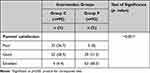

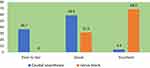

Parents of children in group P were more satisfied than those in group C (Table 4, Figure 5) with no recorded complications for both techniques.

|

Table 4 Comparison Between Two Intervention Groups Regarding Parents’ Satisfaction |

|

Figure 5 Comparison between two intervention groups regarding parents’ satisfaction. |

Discussion

Orthopedic pediatric procedures carry significant postoperative pain with the requirement for hospital admission and the administration of parenteral opioids. Postoperative pain following orthopedic procedures can be severe and significantly impact the postoperative course of patients. Different regional anesthesia (RA) techniques: either neuraxial or peripheral nerves blocks may be used to provide analgesia for pediatric lower limb orthopedic procedures.9

RA provides an effective solution to the dependence on opioids for postoperative pain relief. Despite this the use of RA in children is behind that of adults. However recently the use of RA has gained substantial use in pediatric perioperative care. Largely due to the increased availability and portability of ultrasonography which has helped practitioners to place more successful blocks helps to increase the duration and probably provide a more potent RA technique.10

In this study we compared the US-guided peripheral nerve block to the gold standard analgesic technique (caudal block) in a university hospital that specialized in pediatric orthopedic surgery. This study included 182 pediatrics who underwent unilateral lower limb surgeries were allocated into two groups; group C (pediatrics received caudal analgesia) and group P (pediatrics received peripheral nerve blocks), there was no statistically significant difference between patients’ baseline characteristics as regards to (Age, sex and weight). Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the pain score at two and four hours postoperatively as well as at 16 and 20 h postoperatively. However there was significance at 6, 8, 12, and 24 h postoperatively frequency of analgesia as well as the total postoperative dose of opiates (nalbuphine) showed significant differences with p-values of <0.001. Time to first analgesic (nalbuphine) requirement was significantly less in group C with a mean of (9.6±2.9 h) than in group P with a mean of (15.1±3.5 h). Parents of children in group P were more satisfied than those in group C with no recorded complications for both techniques.

CA is the most widely used analgesic technique in infants and children it has been studied and applied as an analgesic technique in pediatrics with different dermatomal coverage according to the volume of local anesthetic injected for either abdominal lower limb or even lower thoracic surgeries.3

Villalobos et al compared landmark based caudal analgesia with US-guided lumbar plexus block in pediatrics aged 10 to 17 years undergoing elective hip surgeries in a retrospective study and noted no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of opioid requirements in the first 48 h between the two groups with a median of 2.1 mg/kg oral morphine equivalent and secondary outcomes (intraoperative opioid use and length of stay). The reason for the effective comparable duration of the caudal analgesia in their study may be attributed to the use of a solution of ropivacaine 0.2% with 1:200,000 epinephrine and clonidine (1 μg/kg). Whereas in our study no adjuvants were added to the local anesthetic.11 Interested in LPB Sato et al and Liu et al described ultrasound-guided LPB in the supine position combined with transmuscular quadratus lumborum block in pediatrics scheduled for hip surgery through an anterior and posterior approach, respectively.12,13

Our study demonstrated the effectiveness of US-guided lower limb blocks (femoral and sciatic nerve blocks) in providing a more prolonged duration of postoperative analgesia and lesser postoperative analgesic requirements compared to US-guided CA following lower limb pediatric orthopedic surgeries with better parents’ satisfaction. However, this does not mean that US-guided lower limb block is superior to central neuroaxial analgesia as in the first four to six hours both the neuraxial analgesia and the peripheral nerve block provided good comparable analgesia, whereas afterward the analgesia provided by caudal block started to fade.

In contrast CA is typically used for infants and young children, however, the advance in the use of US in regional analgesia helped the success of caudal analgesia in older children, for instance, in our institute it is common to use caudal analgesia as a neuraxial block in children up to 12 years with prolonged duration than spinal anesthesia. Moreover, having the nonoperated limb blocked as well by CA in the older children may be considered as a drawback in this study. However, the child is not usually affected by this drawback because the concentration of local anesthetic used in caudal analgesia does not lead to a dense motor block to the nonoperated limb which will not be distressing to the child. Moreover, postoperative weight bearing and ambulation were not permitted in these children because of the performed orthopedic surgical procedure.

Merrell and Mossetti and Kaye et al described the advances in peripheral nerve blocks upper and lower limb surgeries in children which become easier, safer and more successful by the invention of the ultrasound. Because of the difficulties and inadequacies of the CA and lumbar plexus block studies have been carried out on the use of US-guided peripheral nerve blocks in pediatrics.5,14 DeLong et al found that US-guided fascia iliaca compartment block in pediatrics’ hip and knee surgeries provided comparable analgesia to lumbar plexus block with a more superficial and easier technique and with fewer complications.15

Another two studies compared US-guided femoral nerve block versus systemic analgesics; Marinković et al performed femoral nerve block in pediatric patients who underwent knee surgery. The need for intra- and postoperative analgesics were significantly lower in the block group with an average duration of around eight hours for the block with no encountered complications.16 Turner et al found that patients who received US-guided femoral nerve block for perioperative femur fracture pain management in the emergency department had a longer duration of analgesia required fewer doses of analgesic medications and required fewer nursing interventions than those receiving systemic analgesics alone.17

Black et al reviewed studies aiming at comparing peripheral nerve blocks with systemic opioids in pediatrics femoral fractures. Only one randomized trial on 55 children aged 16 months to 15 years was included comparing anatomically guided FICB versus systemic analgesia with intravenous morphine sulphate. Results suggested that FICB provides better and longer lasting pain relief with less adverse events than intravenous opioids for femoral fractures in children.18

Argun et al in a retrospective study done on pediatrics who underwent orthopedic tumor surgery found that US-guided lower limb blocks provided an enhanced and prolonged postoperative analgesia and reduced the analgesic consumption of patients without significant side effects compared to systemic analgesics with a mean time for the first analgesic requirement of 10.2±6.4.19

When comparing popliteal nerve block with caudal epidural block in children undergoing elective foot surgery. Bumer et al detected comparable and adequate analgesia. But popliteal block was done using landmark plus nerve stimulator technique and not US-guided as in our study.20

Limitations of this study include, but are not limited to, different surgical procedures with variable duration of the surgery, variable innervation of the surgical site and the nerve distribution required for adequate analgesia, the peripheral nerves blocked in this study (femoral and sciatic nerves) do not provide a full block to lumbar and sacral plexuses branches unlike caudal block which provide an adequate block to lumbar and sacral plexuses and lastly, both techniques were done as single shots with no catheter insertion nor adjuvants, which would have prolonged the duration of analgesia.

Conclusion

US-guided lower limb peripheral nerve block is a simple and safe method to provide adequate and more prolonged analgesia compared to US-guided caudal block for lower limb surgeries in pediatrics. However, comparable analgesia was found in the early hours postoperatively.

Data Sharing Statement

Open access will be permitted. To get the data please send an e-mail to [email protected]. Researchers decided to send data when requested.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Pinto N, Sawardekar A, Suresh S. Regional anesthesia options for the pediatric patient. Anesthesiology Clin. 2020;38:559–575. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2020.05.005

2. Walker BJ, Long JB, Sathyamoorthy M, et al. Complications in pediatric regional anesthesia: an analysis of more than 100000 blocks from the pediatric regional Anesthesia network. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(4):721–732. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000002372

3. Wiegele M, Marhofer P, Per-Arne Lonnqvist PA. Caudal epidural blocks in paediatric patients: a review and practical considerations. BJA. 2019;122(4):509. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.11.030

4. Mirjalili SA, Taghavi K Frawley G, Craw S. Should we abandon landmark-based technique for caudal anesthesia in neonates and infants. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(5):511–516. doi:10.1111/pan.12576

5. Merella F, Mossetti V. Ultrasound-guided upper and lower extremity nerve blocks in children. BJA Education. 2020;20(2):42–50. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2019.11.003

6. Ahiskalioglu A, Yayik AM, Ahiskalioglu EO, et al. Ultrasound-guided versus conventional injection for caudal block in children: a prospective randomized clinical study. J Clin Anesth. 2018;44:91–96. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.11.011

7. Shah RD, Suresh S. Applications of regional anaesthesia in paediatrics. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(S1):i114–24. doi:10.1093/bja/aet379

8. Abou Elella R, Adalaty H, Koay YN, et al. The efficacy of the COMFORT score and pain management protocol in ventilated pediatric patients following cardiac surgery. Int J Pediatr and Adoles Med. 2015;2:123–127. doi:10.1016/j.ijpam.2015.11.001

9. Wu JP. Pediatric anesthesia concerns and management for orthopedic procedures. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2020;67(1):71–84. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2019.09.006

10. Guay J Suresh S, Kopp S. The use of ultrasound guidance for perioperative neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2(2):CD011436. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011436.pub3

11. Villalobos MA, Veneziano G, Miller R, et al. Evaluation of postoperative analgesia in pediatric patients after hip surgery: lumbar plexus versus caudal epidural analgesia. J Pain Res. 2019;12:997–1001. doi:10.2147/JPR.S191945

12. Sato M, Hara M, Uchida O. An antero-lateral approach to ultrasound guided lumbar plexus block in supine position combined with quadratus lumborum block using single-needle insertion for pediatric hip surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017;27:1064–1065. doi:10.1111/pan.13208

13. Liu Y, Ke X, Xiang G, Shen S, Mei W. A modification of ultrasound with nerve stimulation-guided lumbar plexus block in supine position for pediatric hip surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2018;28:678–679. doi:10.1111/pan.13419

14. Kaye AD, Green JB, Gennuso SA, et al. Newer nerve blocks in pediatric surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2019;33:447–463. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2019.06.006

15. DeLong L, Krishna S, Roth C, et al. Short communication: lumbar plexus block versus suprainguinal fascia iliaca block to provide analgesia following hip and femur surgery in pediatric-aged patients – an analysis of a case series. Local Reg Anesth. 2021;14:139–144. doi:10.2147/LRA.S334561

16. Marinković D, Simin JM, Drasković B, Kvrgić IM, Pandurov M. Efficiency of ultrasound guided lower limb peripheral nerve blocks in perioperative pain management for knee arthroscopy in children. A randomized study. Med Pregl. 2016;69:5–10. doi:10.2298/MPNS1602005M

17. Turner AL, Stevenson MD, Cross KP. Impact of ultrasound-guided femoral nerve blocks in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(4):227–229. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000101

18. Black K, Bevan C, Murphy N, Howard J. Nerve blocks for initial pain management of femoral fractures in children (Review). Cochrane Library. 2013;(12):1–15. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009587.pub2

19. Argun G, Çayırlı G, Toğral G, Arıkan M, Ünver S. Are peripheral nerve blocks effective in pain control of pediatric orthopedic tumor surgery?Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 2019;30(1):46–52. doi:10.5606/ehc.2019.62395

20. Bumer T, Kashyap L, Arora M, et al. Comparison between caudal epidural block and popliteal nerve block for postoperative analgesia in children undergoing foot surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Res Med Sci. 2020;8(2):560–565. doi:10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20200235

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.