Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 11

Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival of Small Cell Carcinoma of the Salivary Gland: a Population-Based Study

Received 17 September 2019

Accepted for publication 8 November 2019

Published 24 December 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 10749—10757

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S231446

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Ahmet Emre Eşkazan

Jinbo Bai,1,* Fen Zhao,2,* Shuang Pan3

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong 250021, People Republic of China; 2Department of Stomatology, Qilu Children’s Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong 250022, People Republic of China; 3Department of Orthodontics, Jinan Stomatological Hospital, Jinan, Shandong 250001, People Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Correspondence: Shuang Pan

Department of Orthodontics, Jinan Stomatological Hospital, 101 Jingliu Road, Jinan, Shandong 250001, People’s Republic of China

Email [email protected]

Background: Small cell carcinoma (SmCC) of the salivary gland is rare, and the characteristics and survival are not well defined due to only case reports or case series being reported. The present study aimed to describe the clinicopathological characteristics and determine the factors associated with survival of this rare cancer.

Materials and methods: A population-based study was carried out to investigate clinical characteristics and prognosis of SmCC of the salivary gland using prospectively extracted data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database between 1988 and 2016.

Results: Totally, 198 patients with SmCC of the salivary gland were identified with an average age of 72.6±12.4 and a male to female ratio of 3.4:1. The lesions of most patients (167/198) were located in the parotid gland. The median overall survival (mOS) of all patients is 25.0 months. The 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year survival rate was 65.7%, 40.9%, 33.0% and 22.7%, respectively. Surgery could prolong significantly the mOS by almost 17.0 months (28.0 months vs 11.0 months; P<0.01). Radiotherapy, as well as radiotherapy after surgery, could prolong the mOS (PP=0.04). The survival analysis demonstrated that old age (>72 years), lymph node (N3) and distant metastases were independent factors for poor survival, whereas radiotherapy was an independent factor for favorable survival.

Conclusion: Small cell carcinoma of the salivary gland is a rare disease, and old age, lymph node and distant metastases, and radiotherapy were significantly associated with prognosis. In order to understand this disease more thoroughly, more cases with adequate information are required.

Keywords: small cell carcinoma, salivary gland, outcomes, SEER database

Introduction

Small cell carcinomas (SmCCs) are considered the most aggressive type of neuroendocrine carcinomas. According to epidemiological reports, SmCCs arise most frequently in the lung and extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas are rare, only accounting for 2–4% of all SmCCs.1 SmCC of the salivary gland is an extremely rare and aggressive malignancy representing less than 1% of all salivary gland tumors.2 SmCC of the salivary gland could occur in both the major and minor salivary glands, with most cases affecting the parotid glands.3 This rare cancer mainly occurs in men over 50 years of age.4 The patients typically present with a painless mass which could develop rapidly over several months, then emerged gradually with pain, paraesthesia and facial nerve paralysis. Histological examination is the most reliable way to confirm SmCC of the salivary gland, which is defined as a primary malignancy of the salivary gland composed of small, undifferentiation cells with neuroendocrine differentiation.

SmCC often exhibits aggressive behavior associated with higher metastatic potential and poor survival. Similarly, the previous case series found that 50% of SmCC of the salivary gland had regional lymph node invasion, 41.7% of SmCC had distant metastases.2 Surgery and radiotherapy are considered the main route of treatment. Due to earlier detection related to the superficial location of this tumor, SmCC of the salivary gland seems to have favorable survival time compared with other primary sites. Available information from case reports suggests that the most consistent predictors of overall survival for patients may be age, tumor size and metastasis.2,5,6

However, knowledge of SmCC of the salivary gland is currently limited to case reports and small case series. The clinicopathological characteristics and outcome for this entity are not fully clear. Therefore, we performed a retrospective analysis of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland registered in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database to summarize clinical characteristics and overall survival (OS) for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland to delineate features influencing prognosis.

Methods and Materials

Participants

The SEER program is supported by the National Cancer Institute and collects information including cancer incidence and survival from 18 population-based cancer registries throughout the US, covering ~28% of the US population. All patients with a diagnosis of SmCC (ICD-O-3:8041/3, ICD-O-3:8042/3, ICD-O-3:8043/3, ICD-O-3:8044/3, ICD-O-3:8045/3) located in the salivary gland between 1988 and 2016 were identified from the SEER database. Demographic features and clinicopathological characteristics of these patients were extracted using SEER*Stat 8.2.2 software including age at diagnosis, sex, race, primary site, pathological grade, SEER historic stage classification, TNM stage and the use of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. The overall survival information was also identified and extracted from the SEER database, which was defined as the interval from diagnosis until death or the last follow-up.7 Because the SEER research data are publicly available and all data are de-identified, institutional review board approval and informed consent are not required for this study. In addition, all authors have signed the research agreement form and received permission from the SEER to access the database.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data were compared using Student’s t-tests, while categorical data were examined using chi-square tests. The Kaplan–Meier method and the log rank test were used to evaluate the influence of each variable on overall survival. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression survival analysis was utilized to assess the effect of each variable on prognosis. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were extracted from the univariate and multivariate Cox regression models. All statistical analysis was conducted with MedCalc software (Mariakerke, Belgium). A Pvalue less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

A total of 198 patients with SmCC of the salivary gland were identified between 1988 and 2016. Table 1 describes the characteristics of these patients and their treatment regimens. The average age of all patients was 72.6±12.4, with a male to female ratio of 3.4:1. The lesions of most patients (167/198) were located in the parotid gland, while 25 cases were observed in the submandibular gland and 6 cases in the minor salivary gland. Lesions were almost evenly divided between the left and right salivary glands (51% vs 46%%). Among 106 patients with lymph node status, 71 had lymph node metastases. 14 out of 107 patients were diagnosed with distant metastases. Among all 198 included cases, 44 had localized stage, 84 were categorized with a regional stage and 70 had distant stage.

|

Table 1 Characteristics of 198 Patients with Small Cell Carcinoma of the Salivary Gland |

Patient Survival

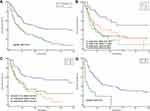

The median overall survival (mOS) of all patients is 25.0 months (Figure 1A). The 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year survival rate was 65.7%, 40.9%, 33.0% and 22.7%. Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by SEER historic stage A classification are shown in Figure 1B. Patients with distant stages had significantly poorer prognosis than those with localized or regional stage (P<0.01 for both). Patients with more advanced disease stages had inferior outcomes: the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rate for patients with localized stage was 84.1%, 55.7% and 50.0%, respectively, compared with just 42.4%, 17.0% and 6.8% in patients with distant stage. SmCC of the salivary gland patients with stage IV disease had the worst prognosis, with a 20.3% 5-year OS rate and 16.0 months of mOS (95% CI 16.0–41.0) (Figure 1C).

Features Influencing Prognosis

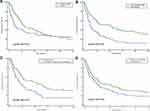

The overall survival for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland became much shorter with increasing age (P<0.01) (Figure 2A), older patients having significantly shorter mOS than younger patients (16.0 months vs 50.0 months). The prognosis for these patients also became much worse with invasion of tumor stage. Patients diagnosed with T1 stage have significantly longer survival time than others (P<0.01), while no significant difference could be observed among patients with T2/T3/T4 (Figure 2B). The prognosis for patients with lymph node metastases was worse than for those without lymph node metastases (P<0.01 for both, Figure 2C). The SmCC of salivary gland patients with distant metastases also had significantly poorer prognosis than individuals without distant metastases (mOS: 2.0 months vs 30 months, P<0.01), the mOS of patients with distant metastases being only 2.0 months (Figure 2D). The survival analysis stratified by marital status also showed that separated/divorced/widowed patients had much worse survival than those from the white population (P=0.03). Besides, no significant association of other features with survival could be observed.

Influence of Treatments on Prognosis

As seen in Figure 3A, surgery could prolong significantly the mOS of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland by almost 17.0 months (28.0 months vs 11.0 months; P<0.01). The patients who received radiotherapy also had a longer survival time than those without radiotherapy (P<0.01, Figure 3B). The mOS of patients receiving radiotherapy was 50.0 months (95% CI 24.0–69.0), while patients without radiotherapy only had OS of 11.0 months (95% CI 8.0–23.0). A total of 5 patients received radiotherapy prior to surgery, while 72 patients received radiotherapy after surgery. The survival analysis showed that the combination of radiotherapy with surgery could significantly improve the patients’ prognoses compared with those with surgery alone (45.0 months vs 18.0 months; P<0.01) (Figure 3C). Besides, patients who received chemotherapy had significantly longer overall survival time than those without chemotherapy (28.0 months vs 20.0 months; P=0.04) (Figure 3D).

|

Figure 3 The effect of treatment on overall survival for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland. (A) Surgery. (B) Radiotherapy. (C) Combination of surgery with radiotherapy. (D) Chemotherapy. |

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Survival Analyses

Table 2 shows the variables that could potentially influence OS using univariate Cox survival analysis. Old age, large tumor stage, lymph node and distant metastases, and late TNM stages were significantly associated with poor prognosis, while the use of radiotherapy, chemotherapy as well as surgery were related to good prognosis (P<0.05 for all, Table 2). Subsequently, multivariate Cox analysis showed that lymph node metastases and distant stage were independent prognostic factors for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland (Table 2). Conversely, radiotherapy was an independent factor for favorable survival and this decreased the risk of death by 44% (HR=0.56, 95% CI 0.12–0.98) for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland.

|

Table 2 Univariate and Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Analyses of Clinical Characteristics for Overall Survival Rates in Patients with SmCC of the Salivary Gland |

Discussion

A previous study has reported SmCC of the salivary gland often found in males with a peak incidence from the fifth to seventh decades of life.2 Servato et al have reported the median age as 64.25 years, with a peak incidence in the eighth decade of life, through the review of 44 cases with SmCC of the salivary gland. Consistent with these results, only 7 patients with SmCC of the salivary gland were diagnosed at less than the fifth decade of life in the present study. Age at diagnosis of patients ranged from 28 to 94 years, and the average age was 72 years, so the literature suggests that our subjects were relatively older. The data for gender also agree with the previous literature that males are predominately affected (~77.3%) with a male to female ratio of 3.4:1. Servato et al also reported a male to female ratio of 2.4:1.2 Besides, our data also showed that the white population is predominately affected by SmCC of the salivary gland (~92.4%). Servato et al also found that all 10 patients with available ethnicity data were Caucasian. One explanation for this high proportion in the white population may be related to the old age when diagnosed with SmCC of the salivary gland. The life expectancy of the white or Caucasian population is always relatively longer than other ethnicities such as black. As one of the highly aggressive tumors, our data also showed that almost all patients (113/114) with SmCC of the salivary gland had poor differentiation or undifferentiation pathological grade. These pathological data further support the high malignancy of this rare cancer.

SmCC often has aggressive behavior associated with a higher metastatic potential whatever the primary site. For example, almost 56.6% of SCLC (small cell lung cancer) patients were staged with extensive-stage disease when diagnosed.8 Similarly, SmCC of the salivary gland also had a relatively high incidence of lymph node or distant metastases. A previous study observed 50% and 41.7% of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland accompanied by lymph node invasion and distant metastases, respectively.2 The distant metastases sites focused on the brain, liver, lung and bones without any particular preference. In the present study, 26.9% of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland were classified into distant stage according to the SEER historic stage, which is consistent with the previous report. From the available information, regional lymph node invasion could be found in about 67% of those cases and distant metastases were found in 13.1% of those cases. The proportion of distant metastases seems to be lower than previous studies, but these differences may be ascribed to inadequate information as 92 cases have no information about distant metastases.

The mOS of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland is 25 months, and for 22.7% of the cases survival could exceed 10 years. The 1- and 5-year survival rate was 65.7% and 33.0%, which is consistent with the 75.3% and 36.6% 1- and 5-year survival rates reported by Servato et al2. Recently, Wakasaki et al reported the outcomes of 21 patients with SmCC originating in the head and neck region, and the 1- and 3-year overall survival rates of these patients were 56% and 37%, respectively.9 All of these reported data showed that SmCC of the salivary gland or other head and neck regions had a much better prognosis than SCLC, or SmCC in the prostate. The more favorable survival rate in SmCC of the salivary gland may be related to the superficial location of this tumor, while yielding early detection, early diagnosis and early treatment.

Older age, separated/divorced/widowed status, large tumor stage, lymph node and distant metastases were related to poor prognosis. Similar to other types of cancer, younger patients often had much better prognosis than older patients.10 As for SmCC of the salivary gland, a previous study also found that age was a statistically significant prognostic factor with the 5-year survival rate of younger patients (<65 years) almost 6-fold (63.5% vs 11.5%) that in older patients (≥65 years). We also observe that marital status could affect prognosis in patients with SmCC of the salivary gland in univariate analysis and this is echoed in previous data on a strong positive correlation between marriage and prognosis of cancer patients that married status had a lower HR of tumor occurrence.11,12 Previous studies suggested that the marital survival benefit for cancer patients is due to improved social and financial support from the family.13 Also, family support may increase compliance or adherence to cancer-related therapy.14–17 In the present study, we observed the negative effect of separated/divorced/widowed status on the outcome of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland in univariate Cox survival analysis, but without statistical significance after adjusting for other confounding factors. The association of marital status and survival is required to be explored in a large cohort of patients in the future.

Tumor stage is also a prognostic factor for these patients. The majority of the patients with T1 could survive more than 10 years, which is significantly longer than other patients. Similar data have been reported in previous studies. Servato et al found tumors with a diameter smaller than 3 cm could have a better prognosis (5-year survival rate: 43.3% vs 11.2%) than larger tumors.2 Also, previous case reports found that patients with tumors larger than 5 cm in diameter could not survive over 24 months.3,18 These findings demonstrate the importance of the size of the primary neoplasm as a predictor of the morbidity and mortality of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland. Except for tumor size, we did not observe any significant association between tumor location and prognosis in the present study.

Lymph node and distant metastases are also found to be another important prognostic factor. For example, all patients with distant metastases died before 5 years of follow-up among the previously reported cases. Our data further confirmed this phenomenon, with the longest survival time of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland only 51 months in the present cohort. As for lymph node metastases, there are some controversial results. Servato et al found that nodal metastasis appeared not to have prognosis significance with no significant difference in 5-year survival time between patients with and without lymph node metastases, but Walters et al’s study reported that all patients with lymph node metastases died of their malignancies.2,3 Our data also support the effect of lymph node metastases on outcome of those patients. Although there is no significant difference in prognosis between N1 patients and N2 patients, the survival time is much better in lymph node negative patients than positive patients.

Surgery and radiotherapy are considered the mainstay of treatment. In the present study, we found only radiotherapy as an independent prognostic factor for good prognosis. Treatment regimens for those patients to achieve local and systemic control of the tumor seek to preserve quality of life and decrease recurrence. If no evidence of metastases could be observed, surgery is suggested and could extend patients’ life expectancy. Here, we observed that cancer-directed surgery significantly improved the median OS for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland by almost 17.0 months. Due to the superficial location of these tumors, radiotherapy is also an effective treatment method. Our data showed that radiotherapy could prolong the mOS of these patients by almost 39.0 months. Adjuvant radiotherapy is also recommended for cases who receive incomplete resection or with increased histological malignancy. Our data also showed that radiotherapy after surgery could significantly improve the patients’ prognoses compared with those with surgery alone. Servato et al also evaluated the effect of chemotherapy after surgery on the outcome of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland, and they found that adjuvant chemotherapy is not significantly associated with survival.2 However, our data showed that chemotherapy could prolong patients’ overall survival. Meanwhile, our data also showed that patients receiving radiotherapy alone had similar survival time to those with the combination of radiotherapy with surgery (data not shown). Although there are some differences in characteristics, such as the patients receiving radiotherapy and surgery having a worse prognostic factor, only radiotherapy is an independent prognostic factor for favorable prognosis. These data further demonstrated the importance of radiotherapy in SmCC of the salivary gland. Therefore, some investigators have proposed radiation therapy alone with or without chemotherapy as an alternative to surgery. This is required to be confirmed in the future.

Of course, there are several limitations that require clarification for accurate interpretation of the results. First, we lacked a lot of information about lymph node metastases, distant metastases and TNM stage. For example, there were 103 patients with unknown tumor stage, 92 patients had no recorded lymph node metastases and 92 patients had no information about distant metastases. Meanwhile, 101 patients lacked TNM stage information. As we know, the AJCC method is more commonly used in the clinical settings, but the SEER summary stage has standardized and simplified staging to ensure consistent definitions over time which could be used as an alternative marker to measure disease progression; however, there are still 23 patients without the SEER summary stage. This point limited our ability to describe the reliability and accuracy of prognostic analysis. Second, we could not evaluate the association of other relevant variables with prognosis such as performance status and pathological biomarker. Servato et al found that the CK20 immunostaining status is a prognostic factor for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland, but we could not evaluate this point due to inadequate information.2,3 We could not account for the effect of potential advances in targeted therapy and immunotherapy, thus limiting our ability to describe treatment patterns for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland. Last, responses to treatment and recurrence rates could not be determined using these data from the SEER. All of these need to be further explored in the future.

In the present study, we described the clinicopathological characteristics and survival of patients with SmCC of the salivary gland using a population-based approach to evaluate the influence of commonly identified features on prognosis. Older age, lymph node and distant metastases, and radiotherapy were significantly associated with prognosis. This is the largest series to discuss clinical characteristics and outcomes for patients with SmCC of the salivary gland, and these results are vital to disease management and future prospective studies for this rare cancer.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Pointer KB, Ko HC, Brower JV, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the head and neck: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. Oral Oncol. 2017;69:92–98. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.04.009

2. Servato JP, da Silva SJ, de Faria PR, Cardoso SV, Loyola AM. Small cell carcinoma of the salivary gland: a systematic literature review and two case reports. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42(1):89–98. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2012.10.004

3. Walters DM, Little SC, Hessler RB, Gourin CG. Small cell carcinoma of the submandibular gland: a rare small round blue cell tumor. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007;28(2):118–121. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.06.013

4. Liu M, Zhong M, Sun C. Primary neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma of the parotid gland: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1275–1278. doi:10.3892/ol.2014.2258

5. Lin YC, Wu HP, Tzeng JE. Small-cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the submandibular gland: an extremely rare extrapulmonary site. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26(1):60–63. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.06.013

6. Kanazawa T, Fukushima N, Tanaka H, et al. Parotid small cell carcinoma presenting with long-term survival after surgery alone: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:431. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-6-431

7. Qin BD, Jiao XD, Zang YS. Primary pulmonary leiomyosarcoma: a population-based study. Lung Cancer. 2018;116:67–72. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.12.015

8. Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4539–4544. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859

9. Wakasaki T, Yasumatsu R, Masuda M, et al. Small cell carcinoma in the head and neck. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2019;128(11):1006–1012. doi:10.1177/0003489419853601.

10. Wang H, Zhang J, Shi F, Zhang C, Jiao Q, Zhu H. Better cancer specific survival in young small cell lung cancer patients especially with AJCC stage III. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):34923–34934. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.16823

11. Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3869–3876. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489

12. Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Key CR, Samet JM. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. JAMA. 1987;258(21):3125–3130. doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03400210067027

13. Gomez SL, Hurley S, Canchola AJ, et al. Effects of marital status and economic resources on survival after cancer: a population-based study. Cancer. 2016;122(10):1618–1625. doi:10.1002/cncr.29885

14. Aizer AA, Paly JJ, Zietman AL, et al. Multidisciplinary care and pursuit of active surveillance in low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(25):3071–3076. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8466

15. Goldzweig G, Andritsch E, Hubert A, et al. Psychological distress among male patients and male spouses: what do oncologists need to know? Ann Oncol. 2010;21(4):877–883. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp398

16. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

17. Yang W, Garzon-Muvdi T, Braileanu M, et al. Primary intramedullary spinal cord lymphoma: a population-based study. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(3):414–421. doi:10.1093/neuonc/now178

18. Pierce ST, Cibull ML, Metcalfe MS, Sloan D. Bone marrow metastases from small cell cancer of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1994;16(3):266–271. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0347

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.