Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Chinese Newlyweds’ Perception and Tolerance Toward Common and Severe Partner Aggression

Received 3 September 2021

Accepted for publication 26 November 2021

Published 10 December 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1981—1991

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S337263

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Zongpei Dai, Yong Zheng

Key Laboratory of Cognition and Personality (Ministry of Education), Southwest University, Chongqing, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Yong Zheng Email [email protected]

Purpose: This study aimed to find the judgment demarcation points of Chinese newlyweds toward common and severe partner aggression, exploring the correlation of asymmetrical commitment and partner aggression tolerance, and revealing the gender differences in aggression tolerance.

Materials and Methods: We conducted two online questionnaire surveys with a total of 629 Chinese newlyweds. Specifically, data for group 1 were collected from 326 Chinese newlyweds for exploratory factor analysis of aggression normality, and data for group 2 from the remaining 303 couples were used for confirmatory factor analysis and inferential statistical analyses.

Results: Results showed that eight items representing non-physical aggression were regarded as common aggression, seven items indicating physical aggression were regarded as severe aggression, and one item was deleted because of disqualification in the exploratory factor analysis. Moreover, individuals showed greater tolerance toward common aggression compared with severe aggression. In terms of commitment, the 303 couples were divided into two groups: asymmetrically committed relationships (ACR) and non-asymmetrically committed relationships (non-ACRs). Through multilevel modeling, we found that couples in ACRs had a greater tolerance for common aggression. In addition, tolerance showed gender differences: husbands displayed a more tolerant attitude toward partner aggression, whether common or severe types.

Conclusion: The study found the demarcation points of aggression normality in Chinese newlyweds broadened the application of commitment in research on partner aggression and emphasized the importance of study of dyadic relationships.

Keywords: aggression normality, commitment, Chinese married couples, common aggression, severe aggression

Introduction

No one hopes to experience violence in a romantic relationship. Nevertheless, people are hurt by those who love them.1,2 Partner aggression is common:3 it refers to any intentional and harmful behavior,4 and adversely affects the feeling of individuals and development of relationships.5,6 Scholars of intimate partner violence (IPV) have divided partner aggression into two forms: common couple violence and patriarchal terrorism.7 In unmarried individual samples, common aggression was more tolerated than severe aggression.8

Even if being in an aggressive relationship is harmful, people do not leave the relationship as soon as they become victims, as is generally believed, but persist in the hurtful relationship.1,9 Why are people willing to stay? Cognitive dissonance theory believes that when people accept directly opposing beliefs, this will cause psychological discomfort, which prompts them to change one of their beliefs to keep them consistent with the other belief.10 The interdependence established between the partners and the positive attitude toward each other may make a person downplay or reinterpret the other party’s negative behavior. Prior research has shown that victims of partner aggression firmly believed that they would be worse off after breaking up and overestimated their unhappiness without their partner, but actually they became better off than they had expected.11 Moreover, worrying about potential negative feedback from others was also an explanation of their willingness to stay.1

In China, the issue of partner aggression in intimate relationships has attracted many scholars’ attention, but little is known about attitudes concerning partner aggression, which adversely affects the relationship’s quality and stability.1,12 Traditional Chinese culture expects families to tolerate domestic violence, which means that marital violence is a culturally acceptable behavior.13 There is a Chinese saying, “beating is a kiss, scolding is love,” which does not encourage domestic violence, but may normalize violence to some extent. Therefore, we need to pay attention to the perceptions and attitudes of people in marriage relationships toward partner aggression. Due to the influence of Chinese traditional culture, married couples may show loose criteria about common and severe aggression, especially newlyweds who are in the beginning of marital relationships and who display high interdependence as well as a high commitment level.

The Demarcation Point of Perception Toward Partner Aggression Among Chinese Newlyweds

How do people perceive partner aggression? Arriaga et al8 divided 16 items (shouted/yelled, insulted/swore, refused to talk, called names, belittled, stated others are better, threatened, destroyed things, blocked the escape, pushed or shoved, slapped/hit, grabbed and shook, hit with a fist, slammed against a wall, beat up, used physical force (items 1–16 in order)) into two types of partner aggression and found that unmarried individuals had the same attitude toward the first six items (named common aggression) and the same attitude toward the last 10 items (named severe aggression). Moreover, in terms of attitudes toward aggression, they revealed people were more tolerant of common aggression and the severe form was more likely to elicit a breakup attitude. Put differently, people were less tolerant of severe aggression. Likewise, Capezza and Arriaga14 demonstrated that people have more negative attitudes toward serious forms of aggression. However, in a marriage relationship, especially at the beginning of marriage, individuals may have a higher commitment level to each other and more independence, which is a protective relationship factor of intolerance of partner aggression.15,16 They, rather than unmarried couples, were less likely to end an unhappy or aggressive relationship. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss differences of perception of aggression normality in a married setting.

Question 1: Where is the cut-off point of different forms of partner aggression for Chinese newlyweds?

Additionally, do individuals have a more accepting attitude toward common aggression, as in Western research results8,14 in Chinese marriages? China is a patriarchal society, and this profoundly affects people’s behavior and lives today.17 A saying in Chinese society is, “fighting at the bedside and peace at the end of the bed,” which mainly implies that in a marriage relationship, normal physical conflicts with no serious intention of harming a partner are allowed and acceptable.18 Therefore, it is necessary to provide Chinese results to investigate the cross-cultural consistency.

Hypothesis 1: Chinese newlyweds are more tolerant toward common aggression than severe aggression.

Why Do They Choose to Tolerate Aggression? The Role of Commitment

Although most people oppose domestic violence, they are not as direct when facing partner aggression, and individuals living with partner aggression are more tolerant of it.1 People relax their vigilance and become vulnerable because they want to feel worthy and loved.19 Aggression from romantic partners was more painful than aggression from outside the relationship,20 and it is very difficult to recover from the pain.21,22 Therefore, it is highly important to explore the reason for this tolerance.

Perhaps people evaluate a partner’s aggression more “benignly” due to the role of commitment. Individuals with higher commitment levels are more likely to adopt positive biases about relationships.23,24 Arriaga1 revealed that the association between violence during conflicts and severely violent joking behaviors was qualified by an interaction with commitment; individuals with higher commitments are more likely to interpret the aggression as just a “joke.” Similarly, the greater the commitment, the greater the tolerance when individuals experience aggression.8 We have observed that these studies are almost all discussed from the perspective of individuals instead of a dyadic perspective.

Based on the theory of interdependence,25 commitment is related to the individual’s emotional investment and a greater association with their partner. The two parties gradually form a sense of an identity of “us,” making the vague relationship determined as an intimate relationship in an environment of mutual dependence and commitment. However, the commitments between partners are not always balanced. When commitment differences between partners reach an imbalance, couples fall into an asymmetrical situation, also known as an asymmetrically committed relationship (ACR). In ACRs, individuals with higher commitment levels than the partner—that is, the more committed partner—showed a lower relationship quality and satisfaction and they were associated with more physical aggression toward their partners as well as more aggression from partners.26 From an individual perspective, individuals in relationships with partner aggression and a higher commitment level show more tolerance for common partner aggression:1,8 commitment, aggression level, and aggression attitude are inextricably linked. From a dyadic perspective, considering the interdependence of both partners, regarding the relationship itself, individuals in ACRs may also show a more tolerant attitude towards partner aggression. Considering the result that individuals with a higher commitment level were associated with more tolerance in a single sample,8 we assume that the same effect would be observed for the more committed partner in an ACR. Therefore, we made two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: From the dyadic perspective, compared with couples in non-ACRs, couples in ACRs would be more tolerant of common partner aggression, while no difference would be observed for severe aggression. Hypothesis 3: From the individual perspective, compared with individuals with a higher commitment score in non-ACRs, the more committed partner in ACRs would be more tolerant of common partner aggression, while no difference would be observed for severe aggression.

Who is More Tolerant: The Husband or the Wife?

The research field of partner aggression always involves the discussion of gender differences.27–29 For example, when evaluating partner violence from the perspective of the observer’s gender, it was found that more women than men believed that the perpetrator’s behavior is more unacceptable.30 For the victim, aggression is more acceptable when they are male,27 and judging from the gender of the perpetrator, men are more likely to commit severe forms of physical abuse and cause serious harm to women.31

Research in China showed the same result: violence by women is viewed as more acceptable.32 Bystander opinions indicated that when the perpetrator is male, people have more negative responses to aggression, and when the victim is female, they may receive more sympathy and protection. From the perspective of couples in aggressive relationships, male college students had a higher tolerance for IPV against women victims (ie girlfriends and wives) compared with their female counterparts,33 and male victims have a less obvious physical response to a partner’s aggression.29 To avoid potential negative comments from others, they may not admit that they were abused by a heterosexual partner.1 Wang34 found that in the case of men assaulting women, some men will exaggerate the truth; in the case of women assaulting men, some men will conceal the truth, which may be due to the shame of being a victim of a beating by a wife. These tendencies embody the traditional and old social concept of the “superior male to inferior female” in China.

Hypothesis 4: Compared with the wife, the husband shows a more tolerant attitude toward partner aggression, regardless of common or severe aggression.

The overall aim of the study was to explore the cut-off point of partner aggression for Chinese newlyweds and investigate the tolerance difference of partner aggression in married settings.

Methods

Participant Samples

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Psychology at Southwest University, China. A total of 836 Chinese newlyweds participated in the study between June 2020 and January 2021. We completed the questionnaire survey in a sequence of collection, screening, and re-collection over a period of six months on an online platform (www.wenjuanwang.com). The data collected would be used only for academic research. Further, informed consent was obtained online. Data for 207 couples were removed because at least one party or both gave evidence of inconsistent, false, or careless responding, such as checking the same option in the forward and reverse statements of the same question. Finally, in the first batch of 450 newlyweds, we retained 326 pairs, and in the second batch of 386 newlyweds, we retained 303 pairs. Ultimately, a total of 629 Chinese newlywed pairs participated. At the time of the study, all couples had been married for no more than two years and had no children. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedure

We recruited two groups of newlywed couples through online recruitment (www.wenjuanwang.com). Participants could browse the public information about the questionnaire on this website and click the link to take the test. Data were collected from the first group of 326 newlywed couples regarding aggression normality to provide data for the exploratory factor analysis. The second batch of couples totaled 303 pairs. They completed the Commitment Inventory, Aggression Normality Scale, Aggression Tolerance Scale, and the Physical Aggression Subscale and Psychological Aggression Subscale from the revised Conflict Tactics Scale.35 Data from the Aggression Normality Scale from the second group (303 couples) were used for confirmatory factor analysis and to verify Question 1; remaining data from them (303 couples) were used to verify the four hypotheses. We strictly controlled the ID numbers of both batches of couples to ensure the data did not overlap. All participants signed the informed consent before participating in the investigation and completed the test without violating the ethical requirements.

Measures

Commitment

To measure internal commitment level, which represents a person’s willingness to sacrifice and dedicate themselves to the other party, we chose the 14-item dedication scale from the Commitment Inventory.36 Participants responded to each item using a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Example items are “I am not seriously attracted to anyone other than my partner” and “I want this relationship to stay strong no matter what rough times we may encounter.” Six of them used reverse scoring, such as “Giving something up for my partner is frequently not worth the trouble.” A large number of studies have confirmed the reliability and validity of this scale.37,38 The mean of 14 items represents the individual commitment score: the higher the score, the higher the commitment level. All participants were measured, but only the data of the second group (n = 303) were recorded and used for verifying hypotheses (M = 5.65, SD = 0.66, and α = 0.86 for men; M = 5.62, SD = 0.61, and α = 0.85 for women).

Aggression Normality

Based on the approach from Arriaga et al,8 we selected the same 16 items used in their research: Shouted/yelled, insulted/swore, refused to talk, called names, belittled, stated others are better, threatened, destroyed things, blocked the escape, pushed or shoved, slapped/hit, grabbed and shook, hit with a fist, slammed against a wall, beat up, and used physical force. The score ranges from 1 (extremely uncommon) to 7 (extremely common). The instruction was: There is no personal pronoun involved, just choose the common degree of certain aggressive behaviors. We used the first batch of data (n = 326) to perform exploratory factor analysis (Promax rotation) on 16 items and retained the items with a factor loading > 0.50 and cross-loading < 0.40. Because the loading for the second item was less than 0.50 on both factors, it was deleted. Finally, we kept a total of 15 items and divided them into two factors: common aggression (Items 1, 3–9) and severe aggression (Items 10–16). Next, we used the second batch of data (n = 303) to perform confirmatory factors analysis on these 15 items.

Aggression Tolerance

Considering the couple’s relationship as background, couples (n = 303) were required to choose to what extent there would be grounds to divorce if the partner was to perform these 16 aggressive behaviors in the Aggression Normality Scale. This practice is based on the procedures of Arriaga et al:8 the 16 items were aggregated into one scale for aggression tolerance. It should be noted that after the factor analysis of the Aggression Normality, Item 2 was deleted. To be consistent, the scoring of Aggression Tolerance Scale does not include Item 2 in this test, so only 15 items were scored. The score ranges from 1 (definitely would not divorce) to 7 (definitely would divorce) (M = 3.44, SD = 1.13, and α = 0.97 for men; M = 3.02, SD = 1.06, and α = 0.97 for women).

Control Variables

Since research findings in the West8,28 indicate aggression in a relationship affects people’s attitude towards aggression, the most common forms of physical aggression and psychological aggression were selected in this study and treated as control variables.

Physical Aggression

We used the Physical Aggression Subscale in the revised Conflict Tactics Scale.35 The subscale has 12 items that ask about the partners aggressive behavior. The sums of the values of the 12-item subscale were analyzed. The higher the score, the higher the physical aggression (M = 5.48, SD = 4.33, and α =0.65 for men; M = 4.41, SD = 3.79, and α =0.54 for women).

Psychological Aggression

To test psychological aggression, we chose the Psychological Aggression Subscale in the revised Conflict Tactics Scale.35 Eight items showed minor and severe psychological aggression. The sums of the values of the eight-item subscale were analyzed. The higher the score, the higher the psychological aggression (M = 7.11, SD = 4.41, and α =0.74 for men; M = 6.76, SD = 4.01, and α =0.61 for women).

Analysis Method

In the first step, SPSS ver. 26.0 was used to conduct Exploratory Factor Analysis on the evaluation scores of couples in the first group (n = 326) on partner aggression, and the cognitive dimension of partner aggression (common aggression and severe aggression) of these couples were analyzed. The second step was to examine the Exploratory Factor Analysis results. The scores of the second group of couples (n = 303) on partner aggression cognition were imported into M-plus for Confirmatory Factor Analysis, and the model fitting was judged according to the model fitting indexes. The analysis of the first two steps was conducted in order to solve Question 1. In the third step, according to the common aggression and severe aggression dimensions, descriptive indicators such as mean and standard deviation were calculated for the spouses’ tolerance of partner aggression in the second group (Hypothesis 1). In the fourth step, we established an individual database and a couple database to explore whether there were differences in aggression tolerance between different couple relationships (Hypothesis 2). HLM7.0 software was used to perform regression analysis of partner aggression tolerance for keeping the independence of the couples. In the last step, the multiple regression in SPSS was used to explore Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Results

Regarding socio-demographic and socio-economic information of participants, in the first group of couples (n = 326), the average age of the women was 26.97 years (22–32 years, SD = 2.13), and for men it was 27.82 years (22–42 years, SD = 2.21). The median number of months the couples had been together before marriage was 26.86 (SD = 15.94), and the average number of months as a married couple was 10.69 (SD = 4.74). In the second group of couples (n = 303), the average age of women was 27.13 years (22–37 years, SD = 2.14) and that of men was 28.07 years (22–38 years, SD = 2.56). The median number of months the couples were together before marriage was 28.59 (SD = 14.88), and the average number of months as a married couple was 8.69 (SD = 5.31).

Regarding the results of Question 1, the study explored the demarcation point of perception toward partner aggression and found that married people in China judged “saying to a partner in an angry or threatening way, ‘you’ll never get away from me’” as the cognitive cutoff point for partner aggression, and considered behaviors such as “shouted or yelled at a partner, refused to talk about an issue with a partner, called a partner names (like ‘ugly’, ‘idiot’), belittled a partner in front of others” to be more common than behaviors like “pushed or shoved a partner, slapped or hit a partner”.

Regarding the results of four hypotheses, three hypotheses were confirmed. First, Chinese newlyweds were more tolerant toward common aggression than severe aggression (Hypothesis 1). Second, compared with couples in non-ACRs, couples in ACRs were more tolerant of common partner aggression, while no difference observed for severe aggression (Hypothesis 2). Third, compared with the wife, the husband showed a more tolerant attitude toward partner aggression, regardless of common or severe aggression (Hypothesis 4). However, there was no significant difference of aggression tolerance between individuals with a higher commitment score in non-ACRs and more committed partner in ACRs, regardless of common or severe aggression (Hypothesis 3).

The Demarcation Point of Perception Toward Partner Aggression

Where is the cut-off point of the perception of partner aggression (Question 1)? Through exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis for two batches of newly married couples, we retained 15 items about aggression normality and found the dividing point between common and severe aggression. Chinese newlyweds classified the first eight items (except the second item) as common aggression, and exploratory factor analysis showed that the factor loading (cross-loading) was orderly: 0.922 (−0.252), 0.275 (0.499, item 2, deleted), 0.882 (−0.134), 0.877 (−0.083), 0.751 (0.104), 0.570 (0.205), 0.864 (−0.075), 0.564 (0.368), 0.558 (0.292), and the last seven as severe aggression, the factor loading (cross-loading) was orderly: 0.520 (0.379), 0.852 (0.020), 0.626 (0.210), 0.912 (−0.068), 0.889 (−0.084), 0.951 (−0.219), 0.873 (−0.108). Confirmatory factor analysis displayed that χ2/df = 2.988, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.066, CFI = 0.925, TLI = 0.911. It can be seen that the Chinese people’s criteria for judging a partner’s aggressive behavior were loose: Items 7, 8, and 9 which should be categorized as severe aggression were categorized as common aggression in this study. This result answers Question 1: we found the cut-off point of perception of different partner aggression. Eight aggression items were regarded as common aggression and seven aggression items were regarded as severe aggression in Chinese newlywed samples.

Compared with severe aggression, do Chinese married couples have a more tolerant attitude toward common aggression (Hypothesis 1)? We put these 16 items into the context of the participants’ marriages and asked them to think about how likely they would choose divorce if the other party exhibited these aggressive behaviors. Since each participant was evaluated for two types of aggression (common aggression and severe aggression), we chose to use a paired sample t-test to explore which type of aggression was most tolerated. The t-test results showed that compared with severe aggression, participants were more tolerant of common aggression (Mcommon aggression = 3.93, SDcommon aggression = 0.05, Msevere aggression = 2.43, SDsevere aggression = 0.05, t = 47.002, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 1 was upheld completely: compared with severe aggression, common aggression was more tolerated, which replicates the results reported in previous research.8

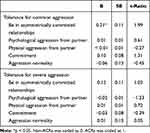

The Positive Impact of Asymmetrically Committed Relationships on Aggression Tolerance

Do ACRs and a high level of commitment moderate couples’ tolerance of partner aggression (Hypotheses 2 and 3)? We used the HLM7.0 software and revealed the positive effects of commitments through a dyadic perspective. ACRs were put in Level 2 and others were put in Level 1. Compared with non-ACRs, if individuals were in ACRs, they showed a more tolerant attitude toward common partner aggressive behavior, B = 0.21, SE = 0.11, p < 0.05. For severe aggression, regardless of the kind of relationships that the couples were in (non-ACRs or ACRs), their attitudes toward partner aggression did not show significant differences, B = 0.12, SE = 0.11, p >0.05 (see Table 1, Hypothesis 2 confirmed). Non-ACRs were coded as 0, ACRs were coded as 1.

|

Table 1 Multilevel Regression Results of Predicting Aggression Tolerance in Asymmetrically Committed Relationships |

For the verification of Hypothesis 3, first, we compared the commitment levels of the more committed partner in ACRs with all individuals in non-ACRs and those (higher commitment score compared with their partner) in non-ACRs. The t-test showed that compared with all individuals in non-ACRs, the more committed partner in ACRs reported higher commitment levels (Mmore committed partner = 6.21, Mnon-ACRs = 5.88, t = −5.94, p < 0.001). Compared with individuals who have a higher commitment score (compared with their partner) in non-ACRs, the more committed partner in ACRs also reported greater commitment levels (Mmore committed in ACRs = 6.21, Mindividual with higher commitment score in non-ACRs = 5.67, t = −10.58, p < 0.001). This result indicated that the more committed partner in ACRs have the highest commitment level. Next, we used regression analysis to confirm Hypothesis 3, which indicated that there was a marginally positive effect of the more committed partner in ACRs toward common aggression, B = 0.33, SE = 0.18, p =0.061 (Table 2), and no significant effect in severe aggression, B = 0.19, SE = 0.17, p >0.05, Hypothesis 3 was not confirmed; individuals with a higher commitment score in non-ACRs were coded as 0 and the more committed partner in ACRs as 1.

|

Table 2 Multiple Regression Results of Prediction of Commitment Level on Aggression Tolerance |

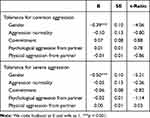

Gender Differences for Aggression Tolerance

Who is more tolerant of partner aggression in a married relationship: men or women (Hypothesis 4)? In terms of a gender difference, we found that compared with wives, Chinese husbands were more tolerant for partner aggression, regardless of its form, which confirmed Hypothesis 4. Table 3 indicated that compared with husbands, wives showed a lower tolerance for partner aggression, whether common aggression (B = −0.39, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001) or severe aggression (B = −0.50, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001, with husband coded as 0 and wife as 1), both showed significant effects, and men were associated with greater tolerance toward partner aggression.

|

Table 3 The Gender Difference on Aggression Tolerance |

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to investigate the perception and tolerance of newly married couples in China toward partner aggression. Regarding the judgment of demarcation points for aggression normality, Chinese couples reported that behaviors referring to non-physical aggression were grouped in the common aggression category and behaviors referring to physical aggression were grouped in the severe form. The result showed that Chinese couples have loose perception criteria toward partner aggression and could clearly judge between physical and non-physical aggression. They further indicated that no matter how serious the non-physical aggression, people generally viewed physical aggression more negatively, which was consistent with previous studies.14,39 This result explains the impact of Chinese traditional culture in people’s perceptions about couple conflict and implies perception asymmetry of non-physical and physical partner aggression: because non-physical aggression does not show the direct “visible” hurt to the individual, people do not feel how serious it is, but when it comes to the physical dimension, people began to become alert, thinking it brings more harm and desperation. This is also borne out by people’s attitudes towards different types of aggression. Participants only needed to perceive the intensity of the aggression from the perspective of a bystander rather than bringing themselves into the role of the victim when answering questions about the cognition of partner aggression. However, participants showed consistent responses when they were required to answer to what degree they would tolerate partner aggression behaviors when they were placed in their own intimate relationship. People were willing to make concessions to the common aggression from their partner, even if it meant less happiness and personal pain.11,21

Why do people tolerate common aggression? Mills40 revealed the positive effects of commitment, finding that individuals with high commitment levels feel less blame for negative behavior from their partner. Committed individuals had stronger emotional bonds with their partner and were more dependent on their partner. Individuals with higher commitment levels toward their partner had a more tolerant attitude toward partner aggression. Further, highly committed individuals do not think partner aggression is related to their unhappiness; they tend to downplay, deny, or just reexplain partner aggression as a joke.1,21

While the positive effects of commitment on aggression tolerance have been widely confirmed from the individual perspective, this study considered the dyadic nature of intimate relationships and discussed the function of commitment from commitment discrepancy in married settings. Unbalanced committed relationships are associated with more tolerant attitudes to common aggression, which not only shows they were less vigilant about aggression in fragile relationships but also further expands the positive effect of commitment duality on tolerance. The level of individual commitment is important in a marriage, but the interdependence of both parties should not be ignored. Commitment discrepancy, as a measure of relationship quality, refers to the likelihood of the break-up of a relationship.26 Exploring people’s tolerance to aggression from the perspective of commitment differences revealed that unstable relationships have a protective effect on partner aggression: in an unhealthy relationship, people’s judgment is not rational, which is consistent with the results obtained by single-sample studies.8,21 In addition, results showed that couples have a consistent attitude toward severe aggression, regardless of the nature of committed relationships. This finding verified previous viewpoints that there is an upper limit for people’s tolerance of partner aggression, and they tend to agree on which acts of partner aggression were severe.8,14

Who is more tolerant? The answer may be men, even though Chinese couples have the highest incidence of mutual violence and there is gender symmetry in physical and psychological aggression.34,41 In most studies on violence in China, men are still considered perpetrators, and the targets are often women.42 At the same time, although many studies have analyzed the perspective of male violence or female victimization,43,44 it may imply that less attention has been paid to male victims in intimate relationship violence. Bates et al27 found that people did not define aggressive behaviors as IPV when the victim was male, and these aggressions were more acceptable. Therefore, perhaps because of gender stereotypes, they were more likely to be tolerant when males suffered partner aggression. Moreover, they may not consider the severity of partner aggression or worry about how others may perceive them.

The study reveals Chinese newlyweds’ views on partner aggression and explores the positive impact of asymmetrically committed relationships on aggression tolerance and shows gender differences regarding tolerance. These results mean that the normality dichotomy between physical and non-physical aggression still exists, even if people have begun to pay attention to the field of mental health. There is much research on depression, aggression, and family health, but publicity about the dangers of non-physical aggression may not have the effect of arousing widespread attention and vigilance, especially among the masses. In addition, the study also provides enlightenment for further exploration from the perspective of implicit attitude cognition.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First and foremost, we only sampled newly married couples and did not investigate individuals in dating relationships. In this case, we were missing important comparative results. Compared with married couples, dating relationships are more unstable and people may be more likely to break up when they experience partner aggression. Therefore, individuals in a dating relationship may have more rigorous judgments about the severity of different aggressive behaviors, which is that more partner aggression items may be regarded as the severe form. Future research should promote comparative investigations of marriage vs dating relationships and explore the commonalities or differences between them. This could clarify the views and attitudes of individuals at different relationship stages toward partner aggression.

Second, the more committed partner in ACRs has only marginally significant effects on aggression tolerance. Newlyweds generally have a high commitment level, so even if some couples were considered ACRs, the gap between the more committed partner in ACRs and others may not be large enough. This raises the problem that the result of the more committed partner in ACRs and those in non-ACRs have no significant difference in partner aggression tolerance could not be generalized to ordinary married couples. Therefore, it is necessary to explore whether high commitment level would be manifested in ordinary married couples. After all, newlyweds have a certain time limit, and the “newlywed” stage cannot last forever.

In addition, the marriage relationship is a relatively long-lasting relationship model in China and focusing only on cross-sectional research is not sufficient for a deep understanding of people’s thoughts and behaviors. These may change over time, and the fluctuation of the commitment level may affect the relationship quality.45 If aggression persists or disappears, the fluctuation of the commitment level may affect the individual’s normality toward aggression tolerance through changes in the number of aggressive behaviors between the couple in a long-term relationship, which may also affect people’s perceptions of aggression tolerance. Therefore, further research should consider investigating changes in people’s attitudes toward partner aggression in the dynamics of time.

Conclusion

The novelty of this study is that it explores the protective effect of commitment level on partner aggression from a dyadic perspective, which broadens the research regarding commitment level on relationship quality. The result of people have greater tolerance for common aggression in asymmetrically committed relationships provides an exploratory route: whether the aggression relationship background moderates the relationship between the committed relationship type and aggression tolerance, which means that the internal influence factor needs to have further exploration.

At the same time, taking the special stage of the newlywed relationship as the investigation object also fills some research gaps in this field. In addition, there has been little research on the asymmetric relationship of commitment in China. Therefore, this study also provides some cross-cultural results for this field and provides some enlightenment for domestic research in this field.

Compared with non-physical aggression as a negative relationship quality indicator, physical violence in intimate relationships tends to receive more attention, which could be reflected in the results of this study. The attitude of different groups toward common aggression implies that a lot of non-physical aggression was inconsistent and it was affected by the nature of the individual’s relationship: the worse the relationship, the greater the tolerance. However, people’s attitudes about severe aggression were consistent, suggesting that people were more resistant to physical aggression than to non-physical aggression, and that they did not compromise once their partner’s aggression reached the realm of physical aggression. These results imply that the dangers of common aggression need more exploration and social attention. Its dangers have been overlooked because it is common in daily life, and the invisible injury is painful.21

Finally, the study highlights the gender difference in the tolerance of aggression in newly married couples. Husbands show higher tolerance in any type of aggression for reasons that need to be further explored.

In general, this study focused on partner aggression tolerance and emphasized the role of commitment difference from the dyadic perspective of newlyweds, shifting from bystander to victim and driving the investigation of partner aggression tolerance with partner aggression cognition. The study enlightens individuals to improve their cognition about partner common aggression, indirectly emphasizing the invisible harm of common aggression, which must not be overlooked, and helps individuals to develop commitment levels in intimate relationships while paying attention to their partners’ commitment level. In doing so, this will effectively detect and control the increase of a commitment level gap and thereby help to establish healthy relationships.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Arriaga XB. Joking violence among highly committed individuals. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17(6):591–610. doi:10.1177/0886260502017006001

2. Arriaga XB, Capezza NM. The paradox of partner aggression: being committed to an aggressive partner. In: Shaver PR, Mikulincer M, editors. Herzliya Series on Personality and Social Psychology. Human Aggression and Violence: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences. American Psychological Association; 2011:367–383.

3. Foshee VA, Benefield T, Suchindran C, et al. The development of four types of adolescent dating abuse and selected demographic correlates. J Res Adolesc. 2009;19(3):380–400. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00593.x

4. Richardson DS. Everyday aggression takes many forms. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(3):220–224. doi:10.1177/0963721414530143

5. Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00514-7

6. Follingstad DR. The impact of psychological aggression on women’s mental health and behavior: the status of the field. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10(3):271–289. doi:10.1177/1524838009334453

7. Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: two forms of violence against women. J Marriage Fam. 1995;57(2):283–294. doi:10.2307/353683

8. Arriaga XB, Capezza NM, Daly CA. Personal standards for judging aggression by a relationship partner: how much aggression is too much? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;110(1):36–54. doi:10.1037/pspi0000035

9. Rusbult CE, Martz JM. Remaining in an abusive relationship: an investment model analysis of nonvoluntary dependence. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21(6):558–571. doi:10.1177/0146167295216002

10. Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford University Press; 1957.

11. Arriaga XB, Capezza NM, Goodfriend W, Rayl ES, Sands KJ. Individual well-being and relationship maintenance at odds: the unexpected perils of maintaining a relationship with an aggressive partner. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2013;4(6):676–684. doi:10.1177/1948550613480822

12. Eastwick PW, Finkel EJ, Krishnamurti T, Loewenstein G. Mispredicting distress following romantic breakup: revealing the time course of the affective forecasting error. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44(3):800–807. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2007.07.001

13. Chan KL. Sexual violence against women and children in Chinese societies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2009;10(1):69–85. doi:10.1177/1524838008327260

14. Capezza NM, Arriaga XB. You can degrade but you can’t hit: differences in perceptions of psychological versus physical aggression. J Soc Pers Relat. 2008;25(2):225–245. doi:10.1177/0265407507087957

15. Rusbult CE, Martz JM, Agnew CR. The investment model scale: measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Pers Relatsh. 1998;5(4):357–387. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00177.x

16. Strube MJ, Barbour LS. The decision to leave an abusive relationship: economic dependence and psychological commitment. J Marriage Fam. 1983;45(4):785–793. doi:10.2307/351791

17. Tang CS, Lai BP. A review of empirical literature on the prevalence and risk markers of male-on-female intimate partner violence in contemporary China, 1987–2006. Aggress Violent Behav. 2007;13(1):10–28. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2007.06.001

18. Breckenridge J, Yang T, Poon AWC. Is gender important? Victimisation and perpetration of intimate partner violence in mainland China. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(1):31–42. doi:10.1111/hsc.12572

19. Murray S, Holmes J, Collins N. Optimizing assurance: the risk regulation system in relationships. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(5):641–666. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641

20. Arriaga XB, Cobb RJ, Daly CA. Aggression and violence in romantic relationships. In: Vangelisti AL, Perlman D, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Cambridge University Press; 2018:365–377.

21. Arriaga XB, Schkeryantz EL. Intimate relationships and personal distress: the invisible harm of psychological aggression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2015;41(10):1332–1344. doi:10.1177/0146167215594123

22. Fuino EL, Carla V, VandeWeerd C. Depression in women who have left violent relationships: the unique impact of frequent emotional abuse. Violence Against Women. 2016;22(11):1397–1413. doi:10.1177/1077801215624792

23. Martz JM, Verette J, Arriaga XB, Slovik LF, Cox CL, Rusbult CE. Positive illusion in close relationships. Pers Relatsh. 1998;5(2):159–181. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1998.tb00165.x

24. Van Lange PA, Rusbult CE. My relationship is better than-and not as bad as–yours is: the perception of superiority in close relationships. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21(1):32–44. doi:10.1177/0146167295211005

25. Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal Relations: A Theory of Interdependence. John Wiley & Sons; 1978.

26. Stanley SM, Rhoades GK, Scott SB, Kelmer G, Markman HJ, Fincham FD. Asymmetrically committed relationships. J Soc Pers Relat. 2017;34(8):1241–1259. doi:10.1177/0265407516672013

27. Bates EA, Kaye LK, Pennington CR, Hamlin I. What about the male victims? Exploring the impact of gender stereotyping on implicit attitudes and behavioural intentions associated with intimate partner violence. Sex Roles. 2019;81(1–2):1–15. doi:10.1007/s11199-018-0949-x

28. Capezza NM, D Intino LA, Flynn MA, Arriaga XB. Perceptions of psychological abuse: the role of perpetrator gender, victim’s response, and sexism. J Interpers Violence. 2017;36(3–4):1414–1436. doi:10.1177/0886260517741215

29. Kim HK, Tiberio SS, Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Squires EC, Snodgrass JJ. Intimate partner violence and diurnal cortisol patterns in couples. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:35–46. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.013

30. Cauffman E, Feldman SS, Jensen LA, Arnett JJ. The (un)acceptability of violence against peers and dates. J Adolesc Res. 2000;15(6):652–673. doi:10.1177/0743558400156003

31. Black M, Basile K, Breiding M, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

32. Wang X, Petula SYH. My sassy girl: a qualitative study of women’s aggression in dating relationships in Beijing. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22(5):623–638. doi:10.1177/0886260506298834

33. Li L, Sun IY, Button DM. Tolerance for intimate partner violence: a comparative study of Chinese and American college students. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35:21–22. doi:10.1177/0886260517716941

34. Wang T. Spousal violence in urban households and its health consequences [In Chinese]. Chin J Sociol. 2006;1:36–60.

35. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001

36. Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54(3):595–608. doi:10.2307/353245

37. Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Should I stay or should I go? Predicting dating relationship stability from four aspects of commitment. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(5):543–550. doi:10.1037/a0021008

38. Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. A longitudinal investigation of commitment dynamics in cohabiting relationships. J Fam Issues. 2012;33(3):369–390. doi:10.1177/0192513X11420940

39. Hammock GS, Richardson DS, Williams C, Janit AS. Perceptions of psychological and physical aggression between heterosexual partners. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(1):13–26. doi:10.1007/s10896-014-9645-y

40. Mills RB, Malley-morrison K. Emotional commitment, normative acceptability, and attributions for abusive partner behaviors. J Interpers Violence. 1998;13(6):682–699. doi:10.1177/088626098013006002

41. Mengtong C, Ling CK. Characteristics of intimate partner violence in China: gender symmetry, mutuality, and associated factors. J Interpers Violence. 2019;36:886260518822340.

42. Ma C. Gender, power, resources, and spousal violence-factors affecting male victimization and female victimization [In Chinese]. Acad Res. 2013;9:31–44.

43. Hou F, Cerulli C, Marsha N, Caine ED, Qiu P. Using confirmatory factor analysis to explore associated factors of intimate partner violence in a sample of Chinese rural women: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019465. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019465

44. Zhou L, Chen X. Conditions and factors for spousal violence against migrant women: empirical research on Xiushui Country, Jiangsu Province [In Chinese]. Chin J Popul Sci. 2015;2:104–114.

45. Knopp K, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Owen J, Markman H. Fluctuations in commitment over time and relationship outcomes. Couple Fam Psychol. 2014;3(4):220–231. doi:10.1037/cfp0000029

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.