Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Changing Kindergarten Teachers’ Mindsets Toward Children to Overcome Compassion Fatigue

Authors Chen F, Ge Y , Xu W, Yu J, Zhang Y, Xu X, Zhang S

Received 22 November 2022

Accepted for publication 15 February 2023

Published 22 February 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 521—533

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S398622

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Fangyan Chen,1 Yabo Ge,1,2 Wenjun Xu,1 Junshuai Yu,1 Yiwen Zhang,1 Xingjian Xu,1 Shuqiong Zhang1

1Institute of Child Development, Jinhua Polytechnic, Jinhua, People’s Republic of China; 2College of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Shuqiong Zhang, Institute of Child Development, Jinhua Polytechnic, 1188 Wuzhou Road, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, 321007, People’s Republic of China, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Kindergarten teachers who empathize with toddlers experience a great risk of burnout and emotional disturbance. This is referred to as compassion fatigue, in which teachers’ empathy experience is reduced. This study proposed a moderated mediation model to identify the risks of compassion fatigue and its protective factors for developing evidence-based clinical interventions.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, self-report measures were administered to 1049 kindergarten teachers to observe their mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, job stress, social support, and compassion fatigue. The PROCESS macro (SPSS 23.0) was used to assess the moderated mediation model.

Results: The results demonstrated that motivation for teacher empathy mediated the negative relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue. Moreover, job stress and social support moderated the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and motivation for teacher empathy. However, this effect was not observed in the negative relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue.

Conclusion: The proposed moderated mediation model was found to be valid. Furthermore, the study findings have practical implications for developing evidence-based interventions for addressing kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue.

Keywords: compassion fatigue, mindsets toward children, empathic motivation, kindergarten teachers

Introduction

Empathy is a multifaceted construct that involves vicariously resonating with others’ experiences (ie experience sharing), actively inferring others’ thoughts and intentions (ie mentalizing), and the motivation to alleviate others’ suffering (ie compassion).1,2 Additionally, it plays a critical role in establishing successful human interactions.3,4 Although providing care can benefits others, it may lead to negative consequences involving cognitive5 and emotional6 costs and compassion fatigue for the providers.7–9 Compassion fatigue, also termed as secondary traumatization, is used to describe the emotional distress resulting from secondhand exposure to another person’s traumatic stress.10,11 In the DSM-5, clinicians and researchers acknowledged secondary traumatization as an indirect exposure to trauma due to “learning that the traumatic events occurred to a close family member or close friend.”12

Compassion fatigue has received substantial attention in clinical psychology over the last three decades.13 Generally, compassion fatigue refers to an individual’s reduced ability or interest in being empathic as a consequence of experiencing others’ traumatizing events.8,9,14,15 Compassion fatigue is typically associated with physical symptoms (eg exhaustion, headaches, and sleep disturbance), behavioral symptoms (eg anger, absenteeism, and attrition), and psychological symptoms (eg emotional exhaustion, depression, and loss of hope).9,13,16,17

Compassion fatigue is a universal psychological state that anyone can experience; it has been studied in many clinical groups,18 including nurses,17,19 physicians,20,21 consultants,22,23 and counselors.24 Recently, researchers in the education field have focused on compassion fatigue.25 Koenig et al conducted a pilot study to explore the relationship between burnout and compassion fatigue among Canadian educators.26 Similarly, Inbar and Shiri adopted a qualitative approach using in-depth interviews to evaluate perceived compassion fatigue among elementary and high school teachers in Israel.27 The existing research demonstrates that elementary and high school teachers are at a risk of developing compassion fatigue.26 However, few studies have focused exclusively on kindergarten teachers, who are likely to be the first to identify children’s suffering and distress. In China, governments are recruiting more kindergarten teachers as part of the implementation of the National Plan for Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development by 2035. For example, the number of kindergarten teachers has increased from 2.43 million in 2017 to 3.19 million in 2021. However, the number of age-appropriate children (aged 3–6 years) has increased from 25.49 million to 48.05 million in the same period.28 Under these high child–teacher ratios, Chinese kindergarten teachers encounter more suffering and adverse emotional events because children need them to empathize on a daily basis; thus, teachers often experience job stress and emotional problems.29 For instance, several researchers believe that kindergarten teachers must interact with children every minute of the workday and tolerate a higher level of emotional demands than teachers of other higher grades.30,31 Moreover, Li et al found kindergarten teachers in China to be under long-term pressure, with more than 50% of them experiencing burnout.32 Thus, similar to other social practitioners, kindergarten teachers provide emotional labor because they experience a high frequency and intensity of empathic situations on a daily basis,33 increasing their risk of developing compassion fatigue. However, few studies have focused on compassion fatigue or identified its risk and protective factors.

The Role of Kindergarten Teachers’ Mindsets Toward Children

According to Figley’s multifactor model of compassion fatigue, empathy is a leading cause of compassion fatigue.8,9 Empathy deficit is considered one of the hallmark symptoms of compassion fatigue. Several recent studies have emphasized that empathy is often a motivating phenomenon.34 For example, the empathic motivation framework theory posits that there exist at least three approaches (positive affect, affiliation, and social desirability) and three avoidances (suffering, material costs, and competition) that drive individuals to approach or avoid empathy, respectively.34 Furthermore, Keysers and Gazzola proposed an empathic propensity-ability dissociation theory, categorizing empathy into ability and propensity dimensions. Empathic ability, a potential and relatively stable trait, is the empathy expressed in optimal situations, while empathic propensity is the tendency of expressing empathy (similar to empathic motivation) when influenced by certain situations.35 These theories suggest that empathy deficits might occur in the absence of ability and the absence of motivation for empathy.36 Therefore, we hypothesized that compassion fatigue, a type of empathy deficit, might also occur due to the absence of empathic motivation.

In addition, the achievement goal theory suggests that mindsets have motivational effects.37 Individuals with malleable mindsets (ie ability is malleable and unstable) have stronger behavioral motivation than those with fixed mindsets (ie capacity is fixed and immutable).38 Moreover, subsequent studies have found that these different mindsets are prevalent in other psychological attributes, such as emotional management and personality.39 Intriguingly, recent studies have found that people have different mindsets regarding empathy. Schumann et al demonstrated that people who believed that empathy could be developed (ie a malleable mindset) could exert more empathic effort than those who thought that empathy could not be developed (ie a fixed mindset).40 Similarly, Weisz et al found that individuals with a malleable perspective of empathy showed stronger empathic motivation and accuracy.41

Teaching is a social interaction between pupils and teachers,42,43 and teachers have mindsets about both themselves and their students (eg students’ abilities).44,45 Intriguingly, these mindsets have motivational effects. Ge et al divided the theories of student abilities according to two different mindsets. Teachers with malleable mindsets regarding students’ abilities may think that their abilities are unstable and can be enhanced through acquired efforts. In contrast, teachers with a fixed mindset regarding students’ abilities may believe that their abilities are unchangeable. These researchers found that teachers’ mindsets regarding students’ abilities could significantly predict teacher empathy and that empathic motivation mediated this relationship.45

According to the empathic motivation framework theory and empathic propensity-ability dissociating theory, empathy is often a motivating phenomenon, and empathic motivation is a significant predictor of empathy.34,35 Thus, we propose that kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children could predict their compassion fatigue and that motivation for teacher empathy plays a mediating role in this relationship.

The Effects of Job Stress and Social Support

In addition to individual factors (eg kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children), compassion fatigue is context-dependent.46 Extensive research has recently established a strong relationship between job stress and compassion fatigue. Choi et al recruited 305 nurses working in children’s hospitals and found a significant positive correlation between job stress and compassion fatigue.47 Similarly, O’Callaghan et al conducted a quantitative cross-sectional survey and showed that job-associated stress could significantly predict compassion fatigue.48 Furthermore, job satisfaction, in contrast to job stress, was highly predictive of decreased compassion fatigue and increased compassion satisfaction. These findings suggest that job stress negatively affects compassion.

Unlike job stress, social support is presumed to be a protective factor that relieves or reduces compassion fatigue. Yu and Gui explored the relationships among social support, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue.49 They reported that compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue directly affect mental health and that perceived social support could directly improve compassion satisfaction and protect against compassion fatigue. Moreover, another study found family support (ie social support) to be a significant contributor to compassion satisfaction and reduced compassion fatigue.50 Robertson et al claimed that specific and accessible support would reduce the potential effects of compassion fatigue and stress-related illnesses among diagnostic radiographers. Thus, we believe that social support might protect kindergarten teachers from compassion fatigue.51

The Present Study

As compassion fatigue is a serious threat to mental health,46,52 identifying the factors that shape compassion fatigue among kindergarten teachers is important for developing clinical interventions. This study investigated the relationships among Chinese kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, compassion fatigue, motivation for teacher empathy, job stress, and social support. Building on previous studies,34,35,40,45,47,50,53 a moderated mediating model was proposed (see Figure 1) to assess the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue is negatively predicted by their mindsets toward children. Hypothesis 2: Motivation for teacher empathy moderates the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue. Hypothesis 3: Job stress moderates the mediating effect among kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, and compassion fatigue. Hypothesis 4: Social support moderates the mediating effect among kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, and compassion fatigue.

|

Figure 1 The conceptual model of moderated mediation framework among the five major variables. |

This study provides new insights into the role of kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and motivation for teacher empathy in the context of compassion fatigue.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The local Kindergarten Review Board approved the study protocol. Advertisements for study participation were broadcast using two instant messaging chat tools (WeChat and QQ Software) popular in China. All participants provided online written informed consent before participating in the survey. A total of 1068 teachers were recruited from Chinese kindergartens in Zhejiang Province. However, 19 participants were excluded from the data screening process because of missing data pertaining to important study variables or because their completion time was less than three minutes. The final valid sample included 1049 kindergarten teachers (1039 females and ten males; Mage = 30.64 years, SDage = 8.17). Among them, 626 teachers (59.7%) were from urban areas, 423 (40.3%) from rural areas, 415 (39.6%) did not have titles, 363 (34.6%) had secondary titles, 251 (23.9%) had primary titles, 19 (1.8%) had senior titles, and 1 (0.1%) had a special title. Participants’ average years of teaching was 9.32 years (SD = 7.92).

Instruments

Kindergarten Teachers’ Mindsets Toward Children

The kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children questionnaire developed by Ge et al.45 Comprising three items (eg “The level of children’s learning abilities is stable to some extent, and children cannot change it”) was used to assess the teachers’ mindsets toward children’s abilities. All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). After converting the reverse-scored items (eg “Children’s learning ability is unlikely to change”), higher scores indicated a more malleable mindset toward children’s learning abilities. This questionnaire has a reasonable reliability when conducted within Chinese culture,45 and it exhibited high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.88) in the present study.

Kindergarten Teachers’ Motivation for Empathy

The kindergarten teachers’ motivation for empathy was measured using the Motivation for Teacher Empathy (MTE) questionnaire developed by Ge et al.45 This questionnaire assessed the intensity of the motivation for teacher empathy in an educational context. The MTE comprises three items according to the concept of empathy (ie cognition, emotion, and behavior). One example item is “When a child is in a bad mood, I want to know what they are thinking at that moment.” The items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree.” Researchers have found that the MTE has good reliability among Chinese teachers.45 The internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s α) was 0.75 in the present study.

Kindergarten Teachers’ Compassion Fatigue

Sun et al revised and normalized the Chinese version of the Compassion Fatigue Short Scale (C-CF Short Scale) based on the CF Short Scale.54,55 The revised scale (13 items; scored on a ten-point Likert scale, from “1 = rarely/never” to “10 = very often.”) is extensively used in Chinese culture.55 For this study, we adapted the Compassion Fatigue for Kindergarten Teachers (CF-kt) Scale based on the C-CF Short Scale.56 Specifically, we modified the items so they were applicable in the context of kindergarten teachers. For example, we revised “I frequently feel weak, tired, or rundown because of my work as a caregiver” to “I frequently feel weak, tired, or rundown because of my work as a kindergarten teacher.” The CF-kt Scale, similar to the CF Short Scale, assesses two aspects of compassion fatigue in kindergarten teachers: job burnout (eight items) and secondary stress (five items). Participants rated the frequency of how often they found each item to be applicable on a ten-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = rarely/never” to “10 = very often.” The confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) showed good structural validity (χ2/df = 12.56, RMSEA = 0.11, CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.87, SRMR = 0.07). Additionally, both the scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.86) and the two aspects of compassion fatigue (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for job burnout and 0.85 for secondary stress) had high internal consistency.

Job Stress

Job stress in kindergarten teachers was measured using the Subjective Stress Scale.57 The scale includes four items (eg “I feel a great deal of stress because of my job” and “Very few stressful things happen to me at work”) rated on a five-point Likert scale from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree.” After appropriate reversals, the sum of the four items indicated the subjective job stress score. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.78.

Social Support

Social support among kindergarten teachers was assessed using the Multi-dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.58 The scale assesses three aspects of social support: support from an individual’s family (eg “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family”), friends (eg “I can count on my friends when things go wrong”), and significant other (eg “There is a special person with whom I can share my joys and sorrows”). Participants indicated their agreement or disagreement with the 12 scale items on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). This scale is widely used and has good reliability and validity in Chinese culture.59 CFA showed good structural validity (χ2/df = 16.74, RMSEA = 0.12, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.04). Additionally, both the scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.95) and the three aspects of social support (Cronbach’s α = 0.88 for family, 0.91 for friends, and 0.89 for the significant other) had high internal consistency.

Demographic Information

Information on the participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, gender, area (urban or rural), teaching experience (eg “How many years have you been working?”), and titles were collected.

Procedure

The research procedures conformed to the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Jinhua Polytechnic Review Board. The study was conducted through a web-based survey via a Chinese survey website (https://www.wjx.cn). Before the survey was conducted, all participants were required to sign an informed consent form (eg “the responses to the questionnaires would be anonymous and confidential, which would be used only for academic research” and “you are at liberty to quit at any time”), and were given instructions on how to complete the survey. Then, the participants filled out a demographic questionnaire and provided responses with regard to the other scales. The collected data included information on the theories of children’s abilities, motivation for teacher empathy, compassion fatigue among kindergarten teachers, job stress, and social support. On average, the participants took approximately 10 minutes to complete this task. Once completed, they were debriefed about the study’s purpose and thanked for their participation.

Statistical Analysis

First, the crucial variables’ descriptive statistics and partial correlations were calculated using SPSS (version 23.0). Second, the hypothesized mediation model (kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children → motivation for teacher empathy (mediator) → kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue) was tested using Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (version 3.3) for SPSS.60 Third, the moderating effects of job stress and social support on motivation for teacher empathy and kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue were tested using Model 2. Finally, the moderating effects of job stress and social support on the mediating effects were assessed using Model 10. After variable centralization, a meaningful indirect effect was identified in the mediation and moderation analyses, depending on whether zero was outside the 95% confidence interval (CI).61 The models were tested using 5000 bootstrap samples.

Results

Preliminary Analyses of the Major Variables

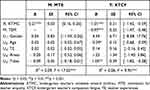

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and partial correlation analysis for the major variables, while controlling for gender, age, teaching experience, areas, and titles. Kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children were significantly and positively correlated with motivation for teacher empathy (r = 0.26, p < 0.001) and social support (r = 0.16, p < 0.001) and was negatively correlated with compassion fatigue (r = −0.18, p < 0.001). Motivation for teacher empathy was significantly and positively correlated with social support (r = 0.37, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with compassion fatigue (r = −0.17, p < 0.001). In addition, kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue was significantly and positively correlated with job stress (r = 0.41, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with social support (r = −0.29, p < 0.001). Job stress was significantly and negatively correlated with social support (r = −0.12, p < 0.001). Finally, we analyzed the demographic differences among the major variables. The results of an independent samples t-test demonstrated that the motivation for empathy for kindergarten teachers from urban areas (M = 18.29, SD = 2.66) was marginally and significantly higher than that of kindergarten teachers from rural areas (M = 17.97, SD = 2.78; t(1047) = 1.87, p = 0.06). No other demographic differences among the major variables were statistically significant.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficients among the Major Variables |

Mediation Model

Based on our hypotheses, we examined the mediating role of motivation for teacher empathy in the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue using Model 4 (the PROCESS macro in SPSS), with gender, age, teaching experience, areas, and titles as covariates. As shown in Table 2, kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children had a significant and positive effect on motivation for teacher empathy (B = 0.21, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.26]), whereas motivation for teacher empathy had a significant and negative effect on kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue (B = −0.97, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.47, −0.48]). Motivation for teacher empathy had a significant and negative direct effect on kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue (B = −1.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.42, −0.59]); the indirect effect on kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue through motivation for teacher empathy was also negative and significant (B = - 0.21, 95% CI [−.34, −1.00]), contributing to 16.98% of the total effect. These results suggest that motivation for teacher empathy partially mediated the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue.

|

Table 2 Results of the Mediation Analysis (Model 4) |

Moderation Model

Model 2 (the PROCESS macro in SPSS) was adopted to examine the moderating role of job stress and social support in the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and motivation for teacher empathy, and between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue. As shown in Table 3, the interaction effect of kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and the moderating variables for motivation for teacher empathy (ie job stress (B = −0.02, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−.04, −0.01]) and social support (B = −0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−.01, −0.01])) were significant. However, these interaction effects were not found in the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue. A simple analysis showed that when both job stress and social support were high (M+1SD), the motivation for teacher empathy was not significantly predicted by kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children.

|

Table 3 Results of the Moderation Analysis (Model 2) |

Moderated Mediation Model

Based on the mediation and moderation analysis, the moderated mediation model was examined using Model 10 (the PROCESS macro in SPSS). As shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, after controlling for the covariates, motivation for teacher empathy was significantly and positively predicted by kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children (B = 0.18, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.23]); this predicted effect was moderated by job stress (B = −0.02, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−.04, −0.01]) and social support (B = −0.01, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−.01, −0.01]). Kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue was significantly and negatively predicted by their mindsets toward children (B = −0.86, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.23, −0.49]), but this predicted effect was not moderated by job stress (B = −0.03, p = 0.62, 95% CI [−.15, 0.09]) or social support (B = 0.001, p = 0.75, 95% CI [−.02, 0.03]). Additionally, kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue was significantly and negatively predicted by motivation for teacher empathy (B = −0.52, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−.99, −0.05]). In summary, these results suggest that the mediating effects of kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, and compassion fatigue were moderated by job stress and social support.

|

Table 4 Results of the Moderated Mediation Analysis (Model 10) |

The conditional indirect effects were analyzed, which revealed that the indirect effects of motivation for teacher empathy were significant among kindergarten teachers who reported low job stress (M-1SD) and social support (M-1SD) (B = 0.37, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.28, 0.45]); low job stress (M-1SD) and high social support (M+1SD) (B = 0.13, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.06, 0.21]); and high job stress (M+1SD) and low social support (M-1SD) (B = 0.22, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.15, 0.30]), but not high job stress (M+1SD) and high social support (M+1SD) (B = - 0.01, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.08]).

Discussion

Kindergarten teachers provide emotional labor that require expressing empathy with high intensity and frequency on a daily basis.30–32 However, existing literature has paid little attention to their compassion fatigue. This study aimed to identify the risk and protective factors that shape kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue by proposing a moderated mediation model for kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, job stress, social support, and compassion fatigue, as shown in Figure 1. As hypothesized, kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue was significantly and negatively predicted by their mindsets toward children, and motivation for teacher empathy significantly mediated this relationship. Moreover, job stress and social support moderated the mediating effect among kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, and compassion fatigue. The present study provides insight into kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, and compassion fatigue, identifying factors for developing clinical interventions.

The Role of Kindergarten Teachers’ Mindsets Toward Children

The present study indicated that kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue was significantly and positively predicted by their mindsets toward children, which supports Hypothesis 1 and is consistent with results from previous studies.40,41,45 Schumann et al measured and induced mindsets of empathic ability, and examined their effects on empathic effort.40 They found that individuals with a malleable mindset about empathy (ie believing empathy can be developed) showed greater empathic effort than individuals with a fixed mindset about empathy (ie believing empathy cannot be extended). Another study supported the role of mindsets of empathic ability and found that creating interventions for a malleable mindset about empathy could strengthen empathic motivation.41 Similarly, Ge et al found that the teachers’ mindsets toward students’ abilities can significantly and positively predict teacher empathy.45 One possible explanation for the current study’s findings is that empathy is a choice based on costs and rewards.62–64 Thus, when kindergarten teachers have a fixed mindset toward children’s abilities and believe that these abilities are unchangeable, they experience feelings of helplessness and even empathize with the children.45 Thus, kindergarten teachers with fixed mindsets toward children’s abilities showed more compassion fatigue than those with malleable mindsets toward children’s abilities.

Mediating Effect of Motivation for Teacher Empathy

The relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and compassion fatigue was mediated by motivation for teacher empathy, supporting our second hypothesis. Following the results of previous studies, motivation for teacher empathy mediated the relationship between mindsets toward students’ abilities and teacher empathy.45 This result is consistent with the empathic motivational framework theory, which posits that empathy is not always an automated process but a motivational phenomenon.34 Thus, empathic motivation has emerged as a new perspective on empathy deficits. Additionally, according to the empathic propensity ability-dissociating theory, empathy results from the interaction of empathy ability and disposition, and variations in empathy may occur due to differences in ability and motivation.35 Kajonius and Björkman found that the Dark Triad (subclinical Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and grandiose narcissism) are generally cognizant of empathizing, but have a low disposition to do so.65 As an empathy deficit,9,14 compassion fatigue among kindergarten teachers might be strongly influenced by empathic motivation.

Furthermore, many studies have highlighted the motivational effect of mindsets, suggesting that motivation for teacher empathy can predict kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue, and motivation for teacher empathy can be predicted by kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children.39,40,45,66 Thus, motivation for teacher empathy mediates the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and their compassion fatigue.

Moderating Effect of Job Stress and Social Support

The current study found that the relationship between kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children and motivation for teacher empathy was moderated by job stress and social support, which is consistent with the results of previous studies.47,48,51 Thus, Hypotheses 3 and 4 were partially supported. When kindergarten teachers have low job stress, their mindset toward children can significantly predict motivation for teacher empathy, under either low or high social support. However, when kindergarten teachers have high job stress, their mindsets toward children can significantly predict motivation for teacher empathy under low social support, but not high social support. The Job Demands-Control Model proposed by Karasek could provide a possible explanation for this result.67 According to this model, the interactions between work demands and job control lead to different psychological working experiences. This can result in either active or passive employment.68 Individuals with low work demands and job control work passively, whereas those with high work demands and job control are more likely to work actively.69 Therefore, high job stress combined with high social support might generate a “good stress” effect for kindergarten teachers, weakening the role of individual factors (ie kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children) in predicting motivation for teacher empathy. Nevertheless, the question of the interaction between job stress and social support and its impact on motivation for teacher empathy is far from answered and is an exciting area for future research.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, it used self-report assessments, which might be susceptible to response bias such as social desirability. Further research is needed to collect more objective indicators of the major variables related to compassion fatigue among kindergarten teachers. Second, a cross-sectional survey design was adopted, which could not confirm the causal relationship among kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, and compassion fatigue. Future research should adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to determine the causal relationships. Finally, the gender ratio was not balanced in the study sample owing to the current preschool education profession. Future research should pay more attention to male kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue.

Implications for Practice

Despite these limitations, the current study provides insights for developing new interventions for kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue from the perspective of motivation. Teaching is a social interaction between pupils and teachers.42 Successful interactions are dependent on understanding pupils’ thoughts and feelings and caring for their welfare; this is known as teacher empathy.70–72 As Swan and Riley stated, “teachers teach content instead of teaching students without empathy.”73 Numerous studies have suggested that teacher empathy plays a pivotal role in the development of students and teachers, including in the contexts of academic performance,74 teacher–student relationships,75 and the professional growth of teachers.76

This study found that compassion fatigue, an empathy deficit phenomenon, was widespread among kindergarten teachers.9 Providing effective interventions is crucial for kindergarten teachers’ mental health and children’s development. Based on the study results, it is possible to change kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children’s abilities from a fixed to malleable mindset to relieve kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue. Weisz et al created an intervention targeting malleable mindsets toward empathy and found a significant effect on empathic motivation, empathy accuracy, and number of friends.41 Furthermore, Gandhi et al found mindsets toward empathy to play a critical role in aggressive behaviors.77 Ge et al conducted a survey and found a close relationship between teachers’ mindsets toward students’ abilities and teacher empathy.45 In summary, to eliminate kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue, they must first change their mindsets toward children.

Conclusions

By analyzing the moderated mediating model examining kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children, motivation for teacher empathy, compassion fatigue, job stress, and social support, this study found that kindergarten teachers’ compassion fatigue can be significantly and negatively predicted by their mindsets toward children; further, motivation for teacher empathy could mediate this relationship. Moreover, job stress and social support moderated this mediating effect. This study suggests that changing kindergarten teachers’ mindsets toward children’s abilities from a fixed to malleable mindset may help relieve their compassion fatigue. Future studies should consider situational factors (eg job stress, social support) for reducing compassion fatigue, improving kindergarten teachers’ mental health, and promoting empathy toward children.

Abbreviations

MTE, Motivation for Teacher Empathy; C-CF Short Scale, Chinese version of the Compassion Fatigue Short Scale; CF-kt, Compassion Fatigue for Kindergarten Teachers; CFA, Confirmatory factors analysis; CI, Confidence interval.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The local Ethics Committee approved the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants who took part in the current study. We are also grateful to the editors and reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to this work, whether in the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data analysis, and interpretation stage, or in all these areas; took part in writing, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

The Evaluation System of Curriculum Ideological and Political Teaching Reform in Higher Vocational Colleges Based on the Concept of “Output-Oriented (OBE)”(The 14th Five-Year Higher Education Teaching Reform Project of Zhejiang Education Department, Zhejiang Education Letter (2021) No.47), the Exploration and Practice of Ideological and Political Path of Professional Courses of Higher Vocational Education for “Two Generations Inheritance”(Curriculum Ideology and Politics of Zhejiang Province in 2022, Zhejiang Education Letter (2022) No.51), and the Curriculum Reform and Classroom Teaching Innovation Project in Jinhua Polytechnic: Exploring the Path of Curriculum Reform in Preschool Education from the Perspective of Competition Promotion Teaching–Taking “Observation and Guidance of Children’s Behavior” as an Example.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Decety J, Cowell JM. Friends or foes. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2014;9(5):525–537. doi:10.1177/1745691614545130

2. Zaki J, Ochsner KN, Ochsner K. The neuroscience of empathy: progress, pitfalls and promise. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(5):675–680. doi:10.1038/nn.3085

3. Batson CD. Altruism in Humans. Altru Humans. 2010;10:1–336. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195341065.001.0001

4. de Vignemont F, Singer T. The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(10):435–441. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.008

5. Cameron CD, Hutcherson CA, Ferguson AM, Scheffer JA, Hadjiandreou E, Inzlicht M. Empathy is hard work: people choose to avoid empathy because of its cognitive costs. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2019;148(6):962–976. doi:10.1037/xge0000595

6. Andreoni J, Rao JM, Trachtman H. Avoiding the ask: a field experiment on altruism, empathy, and charitable giving. J Polit Econ. 2017;125(3):625–653. doi:10.1086/691703

7. Decety J, Yang C-Y, Cheng Y. Physicians down-regulate their pain empathy response: an event-related brain potential study. Neuroimage. 2010;50(4):1676–1682. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.025

8. Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(11):1433–1441. doi:10.1002/jclp.10090

9. Figley C. Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: an overview. Compass Fatigue. 1995;58:1433–1441.

10. Figley CR. Burnout as systemic traumatic stress: a model for helping traumatized family members. In: Burnout in Families: The Systemic Costs of Caring. Boca Raton, FL, US: CRC Press/Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 1998:15–28.

11. Solomon Z, Horesh D, Ginzburg K. Trajectories of PTSD and secondary traumatization: a longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:354–359. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.027

12. APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5.

13. Sinclair S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Venturato L, Mijovic-Kondejewski J, Smith-MacDonald L. Compassion fatigue: a meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:9–24. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003

14. Adams RE, Figley CR, Boscarino JA. The compassion fatigue scale: its use with social workers following urban disaster. Res Soc Work Pract. 2008;18(3):238–250. doi:10.1177/1049731507310190

15. Boscarino J, Adams R, Figley C. Secondary trauma issues for psychiatrists. Psychiatr Times. 2010;27:24–26.

16. Beck CT. Secondary traumatic stress in nurses: a systematic review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2011;25(1):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2010.05.005

17. Hooper C, Craig J, Janvrin DR, Wetsel MA, Reimels E. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and compassion fatigue among emergency nurses compared with nurses in other selected inpatient specialties. J Emerg Nurs. 2010;36(5):420–427. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2009.11.027

18. Kinnick KN, Krugman DM, Cameron GT. Compassion fatigue: communication and burnout toward social problems. Journal Mass Commun Q. 1996;73(3):687–707. doi:10.1177/107769909607300314

19. Potter P, Deshields T, Divanbeigi J, et al. Compassion fatigue and burnout: prevalence among oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(5):565. doi:10.1188/10.CJON.E56-E62

20. El-Bar N, Levy A, Wald HS, Biderman A. Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction among family physicians in the Negev area - a cross-sectional study. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2013;2(1):31. doi:10.1186/2045-4015-2-31

21. Fernando AT, Consedine NS. Beyond compassion fatigue: the transactional model of physician compassion. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(2):289–298. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.014

22. Severn MS, Searchfield GD, Huggard P. Occupational stress amongst audiologists: compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout. Int J Audiol. 2012;51(1):3–9. doi:10.3109/14992027.2011.602366

23. Dasan S, Gohil P, Cornelius V, Taylor C. Prevalence, causes and consequences of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in emergency care: a mixed-methods study of UK NHS Consultants. Emerg Med J. 2015;32(8):588–594. doi:10.1136/emermed-2014-203671

24. Lee W, Veach PM, MacFarlane IM, LeRoy BS. Who is at risk for compassion fatigue? An investigation of genetic counselor demographics, anxiety, compassion satisfaction, and burnout. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(2):358–370. doi:10.1007/s10897-014-9716-5

25. Borntrager C, Caringi JC, van den Pol R, et al. Secondary traumatic stress in school personnel. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2012;5(1):38–50. doi:10.1080/1754730X.2012.664862

26. Koenig A, Rodger S, Specht J. Educator burnout and compassion fatigue: a pilot study. Can J School Psychol. 2018;33(4):259–278. doi:10.1177/0829573516685017

27. Inbar L, Shiri S-A. Managing the emotional aspects of compassion fatigue among teachers in Israel: a qualitative study. J Educ Teach. 2021;47(4):562–575. doi:10.1080/02607476.2021.1929876

28. Ministry of Education in People’s Republic of China. Statistical bulletin on the development of national education in 2021; 2022. Available from: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/202203/t20220301_603262.html.

29. Fan H, Li J, Zhao M, Li H. Mental health of kindergarten teachers: meta-analysis of studies using SCL-90 scale. Adv Psychol Sci. 2016;24(1):9. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.00009

30. Hong X-M, Zhang M-Z. Early childhood teachers’ emotional labor: a cross-cultural qualitative study in China and Norway. Eur Early Child Educ Res J. 2019;27(4):479–493. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2019.1634235

31. Osgood J. Reconstructing professionalism in ECEC: the case for the ‘critically reflective emotional professional’. Early Years. 2010;30(2):119–133. doi:10.1080/09575146.2010.490905

32. Li S, Li Y, Lv H, et al. The prevalence and correlates of burnout among Chinese preschool teachers. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):160. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8287-7

33. Ma Y, Wang F, Cheng X. Kindergarten teachers’ mindfulness in teaching and burnout: the mediating role of emotional labor. Mindfulness. 2021;12(3):722–729. doi:10.1007/s12671-020-01538-9

34. Zaki J. Empathy: a motivated account. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(6):1608–1647. doi:10.1037/a0037679

35. Keysers C, Gazzola V. Dissociating the ability and propensity for empathy. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18(4):163–166. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.011

36. Ge Y, Ashwin C, Li F, et al. The validation of a mandarin version of the Empathy Components Questionnaire (ECQ-Chinese) in Chinese samples. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0275903. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275903

37. Dweck CS. Capturing the dynamic nature of personality. J Res Pers. 1996;30(3):348–362. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1996.0024

38. Dweck CS, Chiu C-Y, Hong -Y-Y. Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: a word from two perspectives. Psychol Inq. 1995;6(4):267–285. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

39. Dweck CS. Mindsets and human nature: promoting change in the Middle East, the schoolyard, the racial divide, and willpower. Am Psychol. 2012;67(8):614–622. doi:10.1037/a0029783

40. Schumann K, Zaki J, Dweck CS. Addressing the empathy deficit: beliefs about the malleability of empathy predict effortful responses when empathy is challenging. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;107(3):475–493. doi:10.1037/a0036738

41. Weisz E, Ong DC, Carlson RW, Zaki J. Building empathy through motivation-based interventions. Emotion. 2021;21(5):990–999. doi:10.1037/emo0000929

42. Holper L, Goldin AP, Shalóm DE, Battro AM, Wolf M, Sigman M. The teaching and the learning brain: a cortical hemodynamic marker of teacher–student interactions in the Socratic dialog. Int J Educ Res. 2013;59(1):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2013.02.002

43. Ge Y, Ding W, Xie R, Kayani S, Li W. The role of resilience and student-teacher relationship in affecting the parent-child separation-PTSS among left-behind children in China. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2022;139(12):106561. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106561

44. Fives H, Buehl MM. Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: what are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us? In: Harris KR, Graham S, Urdan TC, editors. APA Educational Psychology Handbook. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2011:471–499.

45. Ge Y, Li W, Chen F, Kayani S, Qin G. The theories of the development of students: a factor to shape teacher empathy from the perspective of motivation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:163. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.736656

46. Cavanagh N, Cockett G, Heinrich C, et al. Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(3):639–665. doi:10.1177/0969733019889400

47. Choi H, Park J, Park M, Park B, Kim Y. Relationship between job stress and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, burnout for nurses in Children’s Hospital. Child Health Nurs Res. 2017;23(4):459–469. doi:10.4094/chnr.2017.23.4.459

48. O’Callaghan EL, Lam L, Cant R, Moss C. Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in Australian emergency nurses: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2020;48:100785. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2019.06.008

49. Yu H, Gui L. Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction among emergency nurses: a path analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(5):1294–1304. doi:10.1111/jan.15034

50. Cao X, Wang L, Wei S, Li J, Gong S. Prevalence and predictors for compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction in nursing students during clinical placement. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;51:102999. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2021.102999

51. Robertson S, England A, Khodabakhshi D. Compassion fatigue and the effectiveness of support structures for diagnostic radiographers in oncology. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2021;52(1):22–28. doi:10.1016/j.jmir.2020.11.008

52. Vaccaro C, Swauger M, Morrison S, Heckert A. Sociological conceptualizations of compassion fatigue: expanding our understanding. Sociol Compass. 2021;15(2). doi:10.1111/soc4.12844

53. Weisz E. Building Empathy Through Psychological Interventions. Stanford: Stanford University; 2018.

54. Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Figley CR. Compassion fatigue and psychological distress among social workers: a validation study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(1):103–108. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.103

55. Sun B, Hu M, Yu S, Jiang Y, Lou B. Validation of the Compassion Fatigue Short Scale among Chinese medical workers and firefighters: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011279. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011279

56. Sun B, Jiang Y, Lou B, Li W, Zhou X. The mechanism of compassion fatigue among medical staffs: the mediated moderation model. Psychol Res. 2014;7(1):59–65.

57. Motowidlo SJ, Packard JS, Manning MR. Occupational stress: its causes and consequences for job performance. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(4):618–629. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.71.4.618

58. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

59. Zhao J, Peng X, Chao X, Xiang Y. Childhood maltreatment influences mental symptoms: the mediating roles of emotional intelligence and social support. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:415. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00415

60. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Hayes AF, editor. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013.

61. Field A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. London: Sage; 2013.

62. Ferguson AM, Cameron CD, Inzlicht M. When does empathy feel good? Curr Opinion Behav Sci. 2021;39(Suppl. 2):125–129. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.03.011

63. Ferguson AM, Cameron CD, Inzlicht M. Motivational effects on empathic choices. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2020;90(1):104010. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104010

64. Ge Y, Li X, Li F, Chen F, Sun B, Li W. Benefit-cost trade-offs-based empathic choices. Pers Individ Dif. 2023;200(2):111875. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2022.111875

65. Kajonius PJ, Björkman T. Individuals with dark traits have the ability but not the disposition to empathize. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;155(2):109716. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109716

66. Yeager DS, Dweck CS. What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? Am Psychol. 2020;75(9):1269–1284. doi:10.1037/amp0000794

67. Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285–308. doi:10.2307/2392498

68. Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York: Basic Books; 1990:16.

69. Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(10):1336–1342. doi:10.2105/AJPH.78.10.1336

70. Berkovich I, Eyal O. Educational leaders and emotions: an international review of empirical evidence 1992–2012. Rev Educ Res. 2015;85(1):129–167. doi:10.3102/0034654314550046

71. Meyers S, Rowell K, Wells M, Smith BC. Teacher empathy: a model of empathy for teaching for student success. College Teach. 2019;67(3):160–168. doi:10.1080/87567555.2019.1579699

72. Ronen IK. Empathy awareness among pre-service teachers: the case of the incorrect use of the intuitive rule “Same A–Same B”. Int J of Sci and Math Educ. 2020;18(1):183–201. doi:10.1007/s10763-019-09952-9

73. Swan P, Riley P. Social connection: empathy and mentalization for teachers. Pastoral Care in Ed. 2015;33(4):220–233. doi:10.1080/02643944.2015.1094120

74. Warren CA. Empathy, teacher dispositions, and preparation for culturally responsive pedagogy. J Teach Educ. 2018;69(2):169–183. doi:10.1177/0022487117712487

75. Stojiljković S, Djigić G, Zlatković B. Empathy and Teachers’ Roles. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;69:960–966. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.021

76. Jaber LZ, Southerland S, Dake F. Cultivating epistemic empathy in preservice teacher education. Teach Teach Educ. 2018;72(1):13–23. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.02.009

77. Gandhi AU, Dawood S, Schroder HS. Empathy mind-set moderates the association between low empathy and social aggression. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36(3–4):NP1679–1697NP. doi:10.1177/0886260517747604

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.