Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 14

Benralizumab, an add-on treatment for severe eosinophilic asthma: evaluation of exacerbations, emergency department visits, lung function, and oral corticosteroid use

Authors Maselli DJ, Rogers L , Peters JI

Received 18 June 2018

Accepted for publication 18 August 2018

Published 23 October 2018 Volume 2018:14 Pages 2059—2068

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S157171

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Garry Walsh

Diego Jose Maselli,1 Linda Rogers,2 Jay I Peters1

1Division of Pulmonary Diseases and Critical Care, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, TX, USA; 2Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine Mount Sinai – National Jewish Health Respiratory Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Abstract: There are now multiple monoclonal antibodies targeting different inflammatory pathways of severe asthma. Benralizumab is a recently approved monoclonal antibody indicated for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma by targeting a subunit of the IL-5 receptor. Treatment with benralizumab results in significant reductions of blood and tissue eosinophils. Early studies report that this therapy has an adequate safety profile, and this was confirmed in later trials. Phase III studies have shown that benralizumab is effective in reducing the rate of exacerbations and improving asthma symptoms and quality of life in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. Additionally, treatment with benralizumab has resulted in important reductions in the use of chronic oral corticosteroids. In this review, we evaluate the evidence up to date on the efficacy of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma and explore the implications of this therapy in the ever-growing landscape of therapies for severe asthma.

Keywords: MEDI-563, benralizumab, anti-IL-5, IL-5 antibody, IL-5 receptor antibody

Introduction

It is estimated that 5%–15% of asthma patients have difficult-to-control symptoms, a group that accounts for more than 50% of health care utilization related to asthma.1,2 Whereas poor control in these patients is often related to non-adherence, poor inhaler technique, and the impact of comorbidities, approximately 20% of these difficult-to-control patients have true refractory asthma.3

In recent years, several new therapies have been developed to treat patients with asthma who are not adequately controlled with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting bronchodilators. Various monoclonal antibodies or bronchial thermoplasty are therapeutic options for those whose asthma remains uncontrolled despite maximal inhaled therapy. Asthma is heterogeneous across the spectrum of severity of disease, including in those with severe refractory disease. One of the various presentations of severe refractory asthma is the eosinophilic phenotype. Although varying definitions of this phenotype exist based on eosinophil counts in the blood or sputum, this subgroup appears to differentiate from other types of asthma by a number of characteristics as examined in unsupervised cluster analyses and as summarized in several reviews.4–7 Although patients with allergic asthma may have significant peripheral blood eosinophilia, many patients with severe eosinophilic asthma develop symptoms at later stages in life, typically after age 25, have few or no allergies, a normal or moderately elevated immunoglobulin E (IgE); and in some cases, exhibit sensitivity to aspirin and NSAIDs (aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease). They may exhibit persistent airflow limitation, often with peripheral airway involvement or air trapping and dynamic hyperinflation, and may have atypical clinical presentations with predominant dyspnea. Important comorbidities in these patients include chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis and they often present having required repeated sinus surgeries. They are often exacerbation prone, have high health care utilization, and may also present with oral corticosteroid (OCS) dependence. These patients typically exhibit absolute eosinophil counts greater than 300 cells/μL, ranging at times well into the 1,000 cells/μL range or higher. When very high eosinophil counts are present, consideration needs to be given to alternate diagnoses including eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis (EGPA), allergic bronchopulmonary mycoses, and hypereosinophilic syndrome.

In light of the severe symptoms, poor asthma control, and greater morbidity associated with eosinophilic asthma, therapies that target this specific asthma subtype are needed. Benralizumab is a recently approved monoclonal antibody indicated for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma by targeting IL-5rα. IL-5 is produced by TH2 lymphocytes, eosinophils, mast cells, and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2).8,9 In a susceptible host, TH2 lymphocytes and ILC2 cells are the principal source of IL-5 after activation of the type-2 inflammatory pathway in response to allergens and other environmental exposures including viral infections and other irritants.10 IL-5 promotes various key aspects in the life cycle of the eosinophil. In the bone marrow, it stimulates the production and maturation of eosinophil precursors.11 It also increases endothelial adhesion and chemotaxis, resulting in enhanced diapedesis of eosinophils into airways.8 Within the lung, it promotes the terminal maturation and activation of eosinophils.8 Treatment with monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 or IL-5 receptor results in significantly reduced production and activation of eosinophils, and has been associated with improved asthma outcomes. The objective of this review is to evaluate the evidence to date supporting the safety and efficacy of benralizumab for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma and discuss where this agent fits in therapeutic pathways.

For this review, trials and reports were identified from the databases of PubMed/Medline and ClinicalTrials.gov from the US National Institutes of Health and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials. The keywords used for this search included “MEDI-563”, “benralizumab”, “anti-IL-5”, “IL-5 antibody”, or “IL-5 receptor antibody”. No date or language restrictions were used.

Benralizumab

Benralizumab, previously known as MEDI-563, is a humanized afucosylated monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to an epitope within domain 1 of the α subunit of the IL-5 receptor.12,13 Afucosylated monoclonal antibodies lack fucose sugars in the Fc region of the antibody, a process that augments the interaction between benralizumab and the IL-5 receptor and increases the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) compared to targeting the IL-5 ligand directly.13 These characteristics may result in a more complete depletion of eosinophils in the airway lumen without degranulation of eosinophils. An early study in mice and nonhuman primates showed that administration of benralizumab at various doses completely depleted eosinophil counts in the peripheral blood and eosinophil precursors in the bone marrow, without affecting other cellular lineages.13

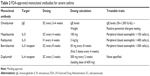

Phase I studies

The observations in murine and nonhuman primate studies described previously were followed by studies in humans (Table 1). A Phase I study explored the effects of benralizumab in patients with mild asthma (n=44) using single, escalating, intravenous (IV) doses in an open-label fashion.14 Peripheral blood eosinophil levels significantly decreased from 270±200 to 10±0.0 cells/μL within 24 hours of administration. Additionally, eosinophil cationic protein, a marker of eosinophil activation, was significantly decreased after treatment from 21.4±17.2 to 10.3±7.0 μg/L, further supporting the anti-eosinophilic activity of the study drug. Low eosinophil counts were maintained up to 12 weeks after treatment. The pharmacokinetic activity was dose-proportional at doses of 0.03 to 3 mg/kg. The safety profile was adequate with mild increases in creatine phosphokinase levels and transient increases of C-reactive protein and IL-6 levels. No major adverse events were observed in these short-term studies.

An additional Phase I study evaluated the safety of benralizumab in patients with eosinophilic asthma compared to placebo.15 Thirteen participants were randomized to receive a single dose of benralizumab IV at a dose of 1 mg/kg or placebo and 14 subjects were randomized to receive 100 mg, 200 mg or placebo subcutaneously (SC). Each participant underwent bronchoscopy with airway mucosal and submucosal endobronchial biopsies and had induced sputum sampled on a separate day. The benralizumab-exposed participants had a significant reduction in airway biopsy eosinophil counts per high power field and peripheral blood eosinophils were undetectable from 7 days after the first dose through the end of the study. Bone marrow aspiration performed in a subset of patients did not identify eosinophil precursors or mature eosinophils 28 days after the initial benralizumab dose without effects on other cellular lineages. No major adverse events were reported.

Phase II studies

The promising results from the Phase I studies were followed by larger dose ranging studies. A Phase IIA study assessed the safety and tolerability of different doses (range 25–200 mg) of benralizumab or placebo given every month SC in adults with asthma.16 As in previous studies, eosinophil counts decreased significantly within days of the administration of benralizumab. Pharmacokinetics were again shown to exhibit linear properties with the area under curve and maximal concentration increments in a dose-proportional fashion.16 The safety profile was similar and adequate at the different doses studied.

An additional dose-ranging Phase IIB, randomized, controlled study tested the effects of benralizumab in 324 eosinophilic and 285 non-eosinophilic asthmatics not controlled with medium- or high-dose ICS.17 Placebo or benralizumab was administered SC at 2 mg, 20 mg or 100 mg every 4 weeks for the initial three doses followed by every 8 weeks for 1 year in patients with eosinophilia. The annual exacerbation rate was reduced only in those that received the 100 mg dose (0.34 vs 0.57, reduction of 41%, 80% CI 11–60, P=0.096). A decrease in the annual rate of exacerbations was observed using the 20 mg and 100 mg doses compared to placebo in those participants with peripheral blood eosinophils of 300 cells/μL or greater (0.30 vs 0.68, reduction 57%, 80% CI 33–72, P=0.015 for 20 mg dose; 0.38 vs 0.68, reduction of 43%, 80% CI 18–60, P=0.049 for 100 mg dose). No improvement in the annual rate of exacerbations was observed in participants without eosinophilia, even at the higher dose. These findings highlight the importance of identifying patients with clinically significant airway eosinophilia or peripheral blood eosinophilia despite standard therapy. Nasopharyngitis and injection site reactions occurred more frequently in the treatment group compared to placebo.

Park et al conducted an additional Phase IIA study in Japan and Korea to evaluate the effects of benralizumab in an East Asian population.18 This multicenter, double-blind trial randomized 106 patients with uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma (>2% sputum eosinophils) to receive either placebo or three different SC doses of benralizumab every 8 weeks (initial two doses separated by 4 weeks) for 52 weeks. All patients had a history of 2–6 exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroids in the prior year. There was a reduction in the annual exacerbation rates compared to placebo by 33, 45, and 36% when patients received 2 mg, 20 mg or 100 mg of benralizumab SC, respectively. In those patients who had a blood eosinophil count >300 cells/μL the reduction in exacerbation rates was more pronounced at 61, 61, and 40%. There was a trend toward improvement in FEV1 and morning peak expiratory flow at doses of 20 and 100 mg of benralizumab. The most common side effects reported were nasopharyngitis, injection site reaction, and upper respiratory tract infection. One final Phase II study evaluated the utility of a single IV infusion of benralizumab of 0.3 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg compared to placebo 7 days following an asthma exacerbation that required an emergency department visit.19 Patients were followed for 12 weeks after the single dose. Benralizumab use was associated with 49% reduction (3.59 vs 1.82; P=0.01) in exacerbations and 60% reduction (1.62 vs 0.65; P=0.02) in hospitalizations. The safety profile was similar to previous studies.

Phase III studies

The SIROCCO trial was the first study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of benralizumab as add-on therapy in uncontrolled severe asthmatics receiving ICS and a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA).20 This Phase III, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial assigned 1,205 subjects (ages 12–75) to placebo, benralizumab 30 mg every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks SC. For those participants with peripheral blood eosinophil counts of more than 300 cells/μL there was significant improvement in the exacerbation rates after 48 weeks with both doses of benralizumab compared to placebo with a relative reduction of 45% (95% CI, 0.60–0.89, P<0.0001) for the every 4 week cohort and 51% (0.53–0.80, P<0.0001) for the every 8 week cohort. The cumulative curves of exacerbation events of the placebo and treatment groups diverged at the 4-week mark, suggesting an early effect. Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 improved in the treatment groups, but asthma-symptom scores only improved in the every 8 week dosing cohort. In participants with peripheral blood eosinophils of less than 300 cells/μL, only those that received benralizumab dosed every 4 weeks had an improvement in exacerbation rates with a relative reduction of 30% (95% CI, 0.65–1.11, P=0.047). All other endpoints were not significantly improved in the subgroup with absolute eosinophil counts less than 300 cells/μL. Overall, benralizumab was well tolerated.

The CALIMA trial had a similar design and duration to the SIROCCO study.20,21 In CALIMA, 1,306 subjects (ages 12–75) were randomized to receive placebo or benralizumab 30 mg every 4 weeks or every 8 weeks SC. In the pre-specified subgroup analysis of those participants with peripheral blood eosinophil counts greater than 300 cells/μL, there was a relative reduction of 36% (95% CI, 0.48–0.74, P=0.0018) found in the every 4 week cohort and 28% (0.54–0.82, P=0.0188) for the every 8 week cohort compared to placebo. Similar to the SIROCCO trial, there were improvements in FEV1 in both treatment doses, but improvement in asthma-symptom scores were only evident in the every 8 week cohort. The safety profile was adequate.

Taking the findings of the SIROCCO and CALIMA trials together, several conclusions can be reached. The effects of benralizumab appear to be greater in those patients with asthma with peripheral blood absolute eosinophil counts of 300 cells/μL or greater. Those patients with frequent exacerbations (three or more) were also found to have the greatest benefit, as demonstrated in the subgroup analysis of the CALIMA trial.20 It is unclear why patients in the SIROCCO trial had greater reductions in exacerbation rates compared to those enrolled in the CALIMA trial, but differences in study populations may be one possible explanation. For instance, in the SIROCCO trial 10%–12% of the population were Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native compared to only <1% in the CALIMA trial.20,21 Additionally, both studies suggest that a more frequent dose initially followed by a longer gap between treatments could deplete eosinophils more effectively initially, but also improve convenience by reducing dosing frequency, and possibly reduce costs compared to other monoclonal therapies depending on pricing.20,21

The findings of SIROCCO and CALIMA trials were encouraging, but these improved outcomes were limited to patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma with peripheral blood eosinophilia greater than 300 cells/μL. The impact of benralizumab in those with mild to moderate asthma was explored in a Phase III, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial, the BISE study. In BISE, 221 patients on low- to medium-dose ICS or low-dose ICS and a LABA received benralizumab every 4 weeks for 12 weeks or placebo.22 Patients exposed to the study drug had an 80 mL improvement from baseline in the pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (95% CI, 0–150, P=0.04). This mild improvement did not differ in those with peripheral blood eosinophil counts 300 cells/μL or greater. The lung function effect in this study was modest, and the study was too brief to evaluate impact on exacerbations. Thus, for now, monoclonal antibodies should be reserved for those with severe, uncontrolled asthma despite standard therapy.

The OCS sparing effect has been one of the most important observations of treatment with agents that block the IL-5 pathway. The ZONDA trial was designed to determine the corticosteroid-sparing effects of benralizumab in oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma patients.23 A total of 220 patients were randomized to receive benralizumab every 8 weeks for 28 weeks (first three doses administered every 4 weeks), every 4 weeks for the duration of the study, or to receive placebo.23 Both regimens of benralizumab resulted in a median reduction in OCS dose of 75% in the two dosing strategies as opposed to 25% in the placebo group (P<0.001). Approximately 50% of the patients exposed to benralizumab were able to completely stop OCS compared to 19% in the placebo group. Approximately 60% of patients achieved OCS doses <5 mg/daily in the treatment doses compared to 33% in the placebo group. The OR of complete discontinuation of OCS was 5.2 (95% CI, 1.92–14.21, P<0.001) for the every 4 weeks group and 4.2 (95% CI, 1.58–11.12, P=0.002) for the every 8 weeks group. Despite the significant reduction or elimination of OCS, treatment with benralizumab resulted in a significant reduction in the annual exacerbation rate of 55% (95% CI, 0.27–0.76, P=0.003) and 70% (95% CI, 0.17–0.53; P<0.001) for the every 4 weeks and every 8 weeks groups, respectively. Although this study supports a significant OCS sparing effect of benralizumab, the ability to reduce the OCS dose in the placebo group (despite an optimization phase prior to randomization) highlights a significant placebo effect in asthma and raises important questions about the treatment of OCS-dependent asthma that require further investigation.23 There were two deaths of patients in the ZONDA study in the every 8 weeks dosing group, one due to cardiovascular disease and the other due to pneumonia in a patient with significant cardiovascular comorbidities. Otherwise, adverse events were similar to earlier studies, but also included hypersensitivity and urticaria; as well as, injection site reactions.

Other IL-5 inhibitors

With the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s approval of benralizumab, there are now three agents available that can be used to treat severe eosinophilic asthma. Mepolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets IL-5 and early studies showed decreases in tissue and circulating eosinophils in asthmatics after therapy.24,25 Various clinical trials have shown the efficacy in multiple outcomes in eosinophilic asthma after therapy with mepolizumab. The DREAM trial was one of the first large trials that demonstrated that mepolizumab was safe and well tolerated in patients with eosinophilic asthma.26 Additionally, patients who received therapy with mepolizumab had a reduced risk of asthma exacerbations compared to placebo. The MENSA trial established that mepolizumab at a dose of 75 mg IV or 100 mg SC was able to significantly reduce the rate of exacerbations compared to placebo in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.27 In addition, the SIRIUS trial, showed that mepolizumab was an effective steroid-sparing agent in asthmatics who required chronic OCS.28 Interestingly, the placebo group also showed significant reductions in OCS dosages.28 Both MENSA and SIRIUS, showed improved asthma symptom scores and had significant reductions in eosinophil counts.27,28 The MUSCA trial, a Phase IIIB, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study evaluated the effect on health-related quality of life.29 Treatment with mepolizumab at 100 mg SC every 4 weeks compared to placebo was associated with significant improvements in the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. Similar to the previous studies, the safety profile was comparable to that of placebo. Additionally, it was shown in the open-label, extension studies of the MENSA and SIRIUS trials that mepolizumab has a lasting and constant effect over time with an adequate safety profile.30 Mepolizumab is indicated for severe asthma with an eosinophilic phenotype (>150 cells/μL) at a dose of 100 mg SC every 4 weeks in patients 12 years or older. Mepolizumab is also unique in that it is the only one of the anti-IL-5 agents with an FDA indication for EGPA, a condition with significant clinical overlap with eosinophilic asthma.31 As the dosing for EGPA differs from that for asthma, the distinction prior to prescribing is important.

Reslizumab, another humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-5, has also been shown to decrease eosinophilic-driven inflammation.32,33 Two large, replicate, Phase III, double-blind, randomized trials revealed that reslizumab given at a dose of 3 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks was associated with improvements in the rates of asthma exacerbations, lung function, and asthma symptom scores compared to placebo.34 Similar findings were confirmed in another Phase III trial using a dose of 3 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks.35 In the same study, a dose of 0.3mg/kg IV was not effective.35 In these trials, the subjects were considered to have eosinophilic asthma if their counts were 400 cells/μL or higher.34,35 Reslizumab has not been found to be effective in subjects without significant peripheral eosinophilia.36 In these studies, no significant differences in the rate of adverse events were observed compared to placebo and overall reslizumab was well tolerated.34–36 Additionally, in an open-label, extension study it was shown that reslizumab had sustained effects with adequate long-term safety.37 This is the only anti-IL-5 drug dosed on the basis of weight that may allow for exploration of treatment in children and obese patients. Weight-based dosing was recommended based on findings from early animal and human dose-ranging studies.38,39 Currently, reslizumab is approved for severe eosinophilic asthma (>400 cells/μL) in patients 18 years or older at a dose of 3 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks.

The role of benralizumab in relation to other asthma biological therapies

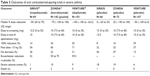

In the evolving landscape of therapies for severe asthma, many more options are now available. Omalizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to free IgE, was approved for the treatment of moderate to severe allergic asthma more than a decade ago. Administration of SC omalizumab results in interruption of the allergic inflammatory pathway and prevents activation of mast cells, antigen-presenting cells, and other inflammatory cells. Four Phase III studies have demonstrated that treatment with omalizumab reduced the rate of asthma exacerbations, decreased emergency room visits and hospitalizations, and significantly improved asthma symptoms in patients with severe allergic asthma compared to placebo.40–43 Nevertheless, a significant proportion of patients may not qualify or not respond to omalizumab, so other therapies have been developed. Benralizumab became the third monoclonal agent that targets the IL-5 pathway for the treatment of severe eosinophilic asthma and the fourth biological overall in the armamentarium of the treatment of severe asthma. Recent publication of Phase III and steroid sparing studies of dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the α subunit of the IL-4 receptor interfering with IL-4 and IL-13 pathways, with promising results increases the likelihood that we may soon have three classes of drugs: anti-IgE, anti-IL-5, and anti-IL-4 monoclonal antibodies, to treat severe asthma44,45 (Table 2). It is recommended that clinicians follow an algorithm using treatable traits to determine which patients are candidates for targeted therapies.1,46 Patients often have overlapping features and there is no consensus on how to choose between these therapies when patients meet all criteria.47,48 A recent editorial has pointed out the need for head-to-head clinical trials comparing these agents to help clarify their respective roles in asthma therapy.49

| Table 2 FDA-approved monoclonal antibodies for severe asthma |

Among the monoclonal antibodies targeting the IL-5 pathway, benralizumab has the unique characteristic of targeting the receptor instead of the ligand. This has the theoretical advantage of not only inhibiting the effects of IL-5, but also through ADCC further degrading the population of tissue and circulating eosinophils. Mepolizumab, for example, may decrease the number of eosinophils, but remaining eosinophils retain their functionality.50 This could explain why not all patients respond in a similar manner. Further, benralizumab has the advantage of less frequent dosing (ie, a longer dosing interval) and complete depletion of eosinophils 24 hours after the initial dose (a characteristic that is thought to be related to the afucosylation of the molecule).51 Despite these potential advantages, a systematic review found no clear superiority among the three anti-IL-5 therapies with regards to exacerbation prevention, lung function improvement, and reduction in asthma symptoms, and some experts consider them essentially equivalent (Table 3).49,52 To this date, no head-to-head study has been done comparing anti-IL-5 therapies, although a small study and recently presented data suggest that weight-adjusted therapy with reslizumab may be beneficial in patients who have not previously responded to mepolizumab, and suggest that there may be differential responses among these therapies.53,54 Importantly, a higher eosinophil count and frequent exacerbations are the characteristics that have been associated with the highest likelihood of improved outcomes with any anti-IL-5 therapy, although clinical efficacy has been shown with lower eosinophil counts with mepolizumab.52,55 Both mepolizumab and benralizumab have been studied in well-designed randomized placebo-controlled OCS sparing studies and both have clinical efficacy as OCS sparing agents. Comparison of data from these two studies may suggest greater steroid sparing efficacy of benralizumab compared to mepolizumab based on median OCS reduction and proportion of patients who achieve complete OCS cessation or dosing <5 mg daily (Table 4).23,28 However, differences in study design, implementation, and patient populations could potentially account for these differences as direct comparative studies have not been performed. Reslizumab has not been specifically studied in a randomized placebo-controlled study as an OCS sparing agent.

| Table 3 Outcomes of oral corticosteroid-sparing trials in severe asthma |

| Table 4 Exacerbation reduction of anti-IL-5 therapies in severe eosinophilic asthma |

Future directions

Ongoing trials are evaluating additional aspects of therapy with benralizumab in severe asthma. The SOLANA trial (NCT02869438) will explore the change of lung function over time in severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma. The ANDHI trial (NCT03170271), is an ongoing, IIIB study, that will further characterize the safety and effectiveness of benralizumab with regards to exacerbation rates, quality of life, and lung function in severe eosinophilic asthma. Finally, the MIRACLE trial (NCT03186209) will test benralizumab in patients with medium-to-high ICS use in addition to LABA in uncontrolled asthma. The results from these trials will add to the safety and efficacy data of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma.

There has been significant interest in investigating different modalities of delivering monoclonal antibodies in asthma, such as home administration by the patient. This could potentially reduce costs and positively affect compliance. The GREGALE study included 116 severe asthmatics who evaluated the home use of an accessorized pre-filled syringe of benralizumab.56 Patients received the first three doses in the study sites and then received two additional doses at home administered by the patient or caregiver. The rate of malfunction of the syringes was 0.17% and patient error was seen in 0.35% of the cases. Home administration was considered reliable and functional, and was associated with improved asthma symptom scores and decreased eosinophil counts. Although these findings are thought provoking, until further evidence supports home use, benralizumab should be administered by a health professional in the office setting.

Beyond asthma, the benefits of benralizumab have been studied in COPD. A Phase IIA, double-blind trial, randomized 101 COPD patients with moderate-to-severe disease and a sputum eosinophil count greater than 3% to receive 100 mg of benralizumab SC or placebo.57 Doses were given every 4 weeks for the first three doses with subsequent dosing every 8 weeks for 48 weeks. Treatment with benralizumab did not reduce exacerbations, but there were modest improvements in lung function.57 The incidence of adverse events was similar in the benralizumab and placebo groups. Results are still pending from two recently completed trials (NCT02138916, NCT02155660) that studied various doses of benralizumab in patients with moderate-to-very-severe COPD and a history of exacerbations. Currently, benralizumab is only approved for severe eosinophilic asthma.

Conclusion

Eosinophilic asthma represents an important proportion of patients with uncontrolled disease, and this subset is linked to increased health care utilization and cost. Benralizumab is a therapeutic option to treat these patients and data support its use for the reduction of exacerbations and improvement of asthma quality of life. There is a paucity of data comparing directly the efficacy among different monoclonal antibodies and future studies may explore this question in a real-life setting. Although the mechanism of action of benralizumab is different than other IL-5 inhibitors, these therapies are considered equivalent by many experts with regards to various outcomes. Ongoing studies will clarify the efficacy and safety of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma, and may help refine where it fits in treatment algorithms for severe asthma compared to current and upcoming monoclonal antibodies.

Disclosure

DJ Maselli: consulting fees from Sanofi Regeneron, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim. L Rogers: consulting fees from Sanofi and received payment for developing educational materials for Astra Zeneca and clinical investigator for Astra Zeneca and Sanofi. The other author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343–373. | ||

Jarjour NN, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER, et al; NHLBI Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP). Severe asthma: lessons learned from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(4):356–362. | ||

Hekking PP, Bel EH. Developing and emerging clinical asthma phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(6):671–680. | ||

de Groot JC, Ten Brinke A, Bel EH. Management of the patient with eosinophilic asthma: a new era begins. ERJ Open Res. 2015;1(1):00024-2015. | ||

Walford HH, Doherty TA. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic asthma: a US perspective. J Asthma Allergy. 2014;7(7):53–65. | ||

Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(4):315–323. | ||

Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):218–224. | ||

Roboz GJ, Rafii S. Interleukin-5 and the regulation of eosinophil production. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999;6(3):164–168. | ||

Klein Wolterink RG, Kleinjan A, van Nimwegen M, et al. Pulmonary innate lymphoid cells are major producers of IL-5 and IL-13 in murine models of allergic asthma. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(5):1106–1116. | ||

Nussbaum JC, van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502(7470):245–248. | ||

Hogan MB, Piktel D, Landreth KS. IL-5 production by bone marrow stromal cells: implications for eosinophilia associated with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(2):329–336. | ||

Koike M, Nakamura K, Furuya A, et al. Establishment of humanized anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha chain monoclonal antibodies having a potent neutralizing activity. Hum Antibodies. 2009;18(1–2):17–27. | ||

Kolbeck R, Kozhich A, Koike M, et al. MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor alpha mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1344–1353. | ||

Busse WW, Katial R, Gossage D, et al. Safety profile, pharmacokinetics, and biologic activity of MEDI-563, an anti-IL-5 receptor alpha antibody, in a phase I study of subjects with mild asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1237–1244. | ||

Laviolette M, Gossage DL, Gauvreau G, et al. Effects of benralizumab on airway eosinophils in asthmatic patients with sputum eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1086–1096. | ||

Gossage D, Geba G, Gillen A, Le A, Molfino N. A multiple ascending subcutaneous (SC) dose study of MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5Rα monoclonal antibody, in adult asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(Suppl 54):1177. Available from: https://www.ers-education.org/home/browse-all-content.aspx?idParent=81890. Accessed September 10, 2018. | ||

Castro M, Wenzel SE, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, versus placebo for uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma: a phase 2b randomised dose-ranging study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(11):879–890. | ||

Park HS, Kim MK, Imai N, et al. A Phase 2a Study of Benralizumab for Patients with Eosinophilic Asthma in South Korea and Japan. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;169(3):135–145. | ||

Nowak RM, Parker JM, Silverman RA, et al. A randomized trial of benralizumab, an antiinterleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, after acute asthma. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(1):14–20. | ||

Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2115–2127. | ||

FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2128–2141. | ||

Ferguson GT, FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab for patients with mild to moderate, persistent asthma (BISE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(7):568–576. | ||

Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Oral Glucocorticoid-Sparing Effect of Benralizumab in Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2448–2458. | ||

Hart TK, Cook RM, Zia-Amirhosseini P, et al. Preclinical efficacy and safety of mepolizumab (SB-240563), a humanized monoclonal antibody to IL-5, in cynomolgus monkeys. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(2):250–257. | ||

Menzies-Gow A, Flood-Page P, Sehmi R, et al. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy induces bone marrow eosinophil maturational arrest and decreases eosinophil progenitors in the bronchial mucosa of atopic asthmatics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(4):714–719. | ||

Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9842):651–659. | ||

Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1198–1207. | ||

Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1189–1197. | ||

Chupp GL, Bradford ES, Albers FC, et al. Efficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(5):390–400. | ||

Lugogo N, Domingo C, Chanez P, et al. Long-term Efficacy and Safety of Mepolizumab in Patients With Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: A Multi-center, Open-label, Phase IIIb Study. Clin Ther. 2016;38(9):2058–2070. | ||

Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, et al. EGPA Mepolizumab Study Team, et al. Mepolizumab or Placebo for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(20):1921–1932. | ||

Kips JC, O’Connor BJ, Langley SJ, et al. Effect of SCH55700, a humanized anti-human interleukin-5 antibody, in severe persistent asthma: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(12):1655–1659. | ||

Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, et al. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(10):1125–1132. | ||

Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(5):355–366. | ||

Bjermer L, Lemiere C, Maspero J, Weiss S, Zangrilli J, Germinaro M. Reslizumab for Inadequately Controlled Asthma With Elevated Blood Eosinophil Levels: A Randomized Phase 3 Study. Chest. 2016;150(4):789–798. | ||

Corren J, Weinstein S, Janka L, Zangrilli J, Garin M. Phase 3 Study of Reslizumab in Patients With Poorly Controlled Asthma: Effects Across a Broad Range of Eosinophil Counts. Chest. 2016;150(4):799–810. | ||

Murphy K, Jacobs J, Bjermer L, et al. Long-term Safety and Efficacy of Reslizumab in Patients with Eosinophilic Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1572–1581. | ||

Egan RW, Athwal D, Bodmer MW, et al. Effect of Sch 55700, a humanized monoclonal antibody to human interleukin-5, on eosinophilic responses and bronchial hyperreactivity. Arzneimittelforschung. 1999;49(9):779–790. | ||

Kips JC, O’Connor BJ, Langley SJ, et al. Effect of SCH55700, a humanized anti-human interleukin-5 antibody, in severe persistent asthma: a pilot study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(12):1655–1659. | ||

Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(2):184–190. | ||

Solèr M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(2):254–261. | ||

Ayres JG, Higgins B, Chilvers ER, Ayre G, Blogg M, Fox H. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-immunoglobulin E therapy with omalizumab in patients with poorly controlled (moderate-to-severe) allergic asthma. Allergy. 2004;59(7):701–708. | ||

Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy. 2005;60(3):309–316. | ||

Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Glucocorticoid-Dependent Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2475–2485. | ||

Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2486–2496. | ||

Israel E, Reddel HK, Severe RHK. Severe and Difficult-to-Treat Asthma in Adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(10):965–976. | ||

Menzella F, Galeone C, Bertolini F, Castagnetti C, Facciolongo N. Innovative treatments for severe refractory asthma: how to choose the right option for the right patient? J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:237–247. | ||

Albers FC, Müllerová H, Gunsoy NB, et al. Biologic treatment eligibility for real-world patients with severe asthma: The IDEAL study. J Asthma. 2018;55(2):152–160. | ||

Drazen JM, Harrington D. New Biologics for Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2533–2534. | ||

Kelly EA, Esnault S, Liu LY, et al. Mepolizumab Attenuates Airway Eosinophil Numbers, but Not Their Functional Phenotype, in Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(11):1385–1395. | ||

Matera MG, Calzetta L, Rinaldi B, Cazzola M. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic drug evaluation of benralizumab for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13(9):1007–1013. | ||

Cabon Y, Molinari N, Marin G, et al. Comparison of anti-interleukin-5 therapies in patients with severe asthma: global and indirect meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(1):129–138. | ||

Mukherjee M, Aleman Paramo F, Kjarsgaard M, et al. Weight-adjusted Intravenous Reslizumab in Severe Asthma with Inadequate Response to Fixed-Dose Subcutaneous Mepolizumab. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(1):38–46. | ||

Mylvaganam R, Rogers L. A Real World, Single Center Experience of Patients with Severe Eosinophilic Asthma Treated with Two Novel Biologics antagonist to IL-5; Mepolizumab and Reslizumab. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A1396. | ||

Fitzgerald JM, Bleecker ER, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Predictors of enhanced response with benralizumab for patients with severe asthma: pooled analysis of the SIROCCO and CALIMA studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(1):51–64. | ||

Ferguson GT, Mansur AH, Jacobs JS, et al. Assessment of an accessorized pre-filled syringe for home-administered benralizumab in severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:63–72. | ||

Brightling CE, Bleecker ER, Panettieri RA, et al. Benralizumab for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sputum eosinophilia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(11):891–901. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.