Back to Journals » Clinical Optometry » Volume 13

Attitude Towards Traditional Eye Medicine and Associated Factors Among Adult Ophthalmic Patients Attending University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital-Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center, Northwest Ethiopia

Authors Eticha BL , Alemu HW , Assaye AK , Tilahun MM

Received 31 August 2021

Accepted for publication 10 November 2021

Published 2 December 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 323—332

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTO.S335781

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Mr Simon Berry

Biruk Lelisa Eticha, Haile Woretaw Alemu, Aragaw Kegne Assaye, Mikias Mered Tilahun

Department of Optometry, School of Medicine, University of Gondar, Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Gondar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Mikias Mered Tilahun

Department of Optometry, School of Medicine, University of Gondar, Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, PO Box: 196, Gondar, Ethiopia

Tel +251 927270318

Fax +251 58-114 1240

Email [email protected]

Background: Traditional eye medicine is a form of biologically based therapies, practices, or partially processed organic or inorganic agents that can be applied to the eye and lead to a blinding complication. Attitude towards those medicines plays a pertinent role in the practice of those traditional eye medicines.

Objective: To determine attitude towards traditional eye medicine and associated factors among adult ophthalmic patients attending University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital-Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

Methods: A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted on 417 newly presenting adult ophthalmic patients who were selected by using a systematic random sampling method from June 22 to August 11, 2020. The data from the interview-based structured questionnaire were entered into Epi Info 7 and analyzed by SPSS 20. Frequency and cross-tabulations were used for descriptive analysis. Association between variables was analyzed using binary logistic regression through the enter method with a 95% confidence interval.

Results: A total of 417 subjects with a 98.8% response rate have participated in the study. Of the total study subjects, 60.7% (253) (95% CI: 19– 26%) had a positive attitude towards traditional eye medicine. Residing in a rural area (AOR=6.46 (95% CI: 2.89– 14.45)), positive family history of traditional eye medicine use (AOR=8.01 (95% CI: 4.17– 15.37)) and availability of traditional healer (AOR=19.43 (95% CI: 12.06– 31.64)) were significantly associated with a positive attitude towards traditional eye medicine.

Conclusion and Recommendation: Most adult ophthalmic patients had a positive attitude towards traditional eye medicine. Residing in a rural, availability of a traditional healer, and positive family history of traditional eye medicine use had a significant positive association with a positive attitude. Educating the traditional healers on safe practices is crucial in reducing the burden.

Keywords: attitude, traditional healer, traditional eye medicine, Ethiopia, Gondar

Introduction

World Health Organization (WHO) defines Traditional medicine (TM) as

the total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental or social imbalance.1

Traditional eye medicine (TEM) is a form of biologically based therapies, practices, or partially processed organic or inorganic agents that can be applied through different routes of administration to achieve a desired ocular therapeutic effect.2

Some 80% of the world’s population meets their need for drugs with herbal drugs that support the estimated 80% of the developing nation population’s dependency on herbal medicine.3 Likewise, an extremely large proportion of the East African and the Ethiopian population rely on traditional healers (TH).4 In our country Ethiopia, TEM use is a large carried out practice all over the country.5

Honey, human saliva, soil, breast milk, herbal extract, linseed (Linum usitatissimum), “damakesie” (Ocimum species), Potato (Solanum tuberosum), and Milk are among the most well-known forms of TEM in East Africa and Ethiopia as well.6–9

Some plants might have a potential anti-biotic effect,10 few of the TEM are harmless and may be beneficial,11,12 whereas complications including keratitis, endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, staphyloma, and visual reduction or loss have been revealed.7,13,14 People exposed to those complications will face visual disability causing a physical, economic, and psychological disturbance that compromises their quality of life.15

Despite progress seen on higher institutions of Ghana and South Africa in promoting the training of TM practitioners and the local cultivation of medicinal plants, the remaining African countries continue to stay with a scarcity of policies, their implementation, and inadequate research infrastructure.16,17 In some Asian nations and Malawi, THs practice supported by a well-developed training manual has been established and implemented in collaboration with modern medical practice.14,18,19

By the year 1942, Ethiopia formally recognized TM and the legality of the practice was acknowledged. To bring traditional and modern medical practitioners together, Meetings and workshops have been organized, while there is no training program exists on TM and guidelines for training THs.5

Attitude towards TEM was a major modifiable factor to reduce this blinding phenomenon. Figure out of an attitude of adult ophthalmic patients towards TEM and factors that can associate with play a vital role in future longitudinal intervention in the aim of halting the burden of the practice of TEM.

In the country over 100 million and with limited eye care infrastructure, most population rely on TEM. So determining a major contributor factor towards TEM will play a significant role for decision-makers to make an evidence-based intervention. This study conducted on adult ophthalmic patients and socio-culturally diversified communities will probe all-inclusive results and impact.

Objectives

Main Objective

To determine attitude towards traditional eye medicine and associated factors among adult ophthalmic patients attending University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital-Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

Specific Objectives

To determine attitude towards TEM among adult ophthalmic patients attending University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital-Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

To identify associated factors that influence attitude towards TEM among adult ophthalmic patients attending University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital-Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center, Northwest Ethiopia, 2020.

Methodology

Study Design

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was used to assess attitude towards traditional eye medicine and associated factors among adult ophthalmic patients.

Study Area and Period

The study was conducted at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital-Tertiary Eye Care and Training Center from June 22 to August 11, 2020. It is located in Gondar city (738 kilometers away from Addis Ababa), which is the capital of the Central Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, Northwest Ethiopia.

The center has been contributing to the reduction in blindness in Gondar and surrounding catchment areas by providing comprehensive eye care services for roughly 14 million people of 10 zones of Northwest Ethiopia covering North Gondar, West Gondar, Central Gondar, South Gondar, Gondar city, Bahir Dar city, West Gojam, Awi, Metekel, and Western Tigray. About 1496 new patients are being served in the outpatient department per month. And it is a training and research center. (Unpublished sources).

To address clients residing in remote areas, it provides health education, refraction (with spectacle provision), medical and surgical eye disease intervention with formal and outreach programs.

Source Population and Study Population

All-new adult ophthalmic patients presenting to UoGCSH-TECTC.

Inclusion Criteria

New adult ophthalmic patients presenting to UoGCSH-TECTC.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who are unable to communicate.

Patients with serious illness.

Sample Size Determination

The Sample Size for First Objective

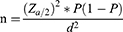

The sample size needed to assess attitude towards TEM is determined by using a single population proportion formula on the following assumption.

Level of significance (α): 5% (with a confidence level of 95%), Marginal error: 5% P: 0.487 (Attitude, practice and associated factors among adult residents towards traditional eye medicine in Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia).9

The Z-value of 1.96 was used at 95% CI (n: sample size, P: proportion, d: marginal error).

n = 384

The total sample size (n) with a 10% nonresponse rate becomes 422.

The Sample Size for the Second Objective

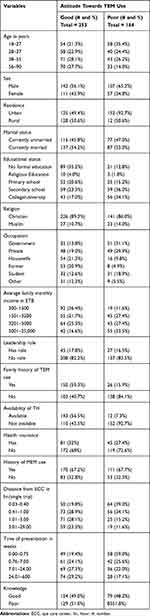

By taking the above study conducted in Gondar, Ethiopia, again sex, TH availability, and family history of TEM use were considered as the main significant factors for TEM use.

The sample size needed to assess the associated factors was calculated separately by using EPI INFO 7 with the following assumptions.

Level of significance = 5%.

Non-response rate = 10%.

Power = 80%.

After comparing all the results above, 422 has taken as the final sample size to determine attitude towards TEM and associated factors (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Statistics Considered for Calculating Sample Size for Objective Two |

Sampling Techniques and Procedures

A systematic random sampling method was used to select the participants. The center has the potential to provide service for about 1496 new patients per month in the outpatient department, but the pandemic COVID-19 diminishes the average expected number of patients to be 530 in a month. The calculated “K” was 2 (N = averagely expected number of patients come to hospital per day 26, n = averagely expected number of samples to be collected per day 12; K = 26/12 = 2). The lottery method was used to draw the 1st sample of the first 2 samples and continues with every Kth interval for the sampling period.

Dependent Variable

Attitude towards traditional eye medicine.

Independent Variables

Socio-demographic variables: age, sex, occupation, educational status, religion, residence, income status, marital status, community leadership role.

Personal factors: Family history of TEM use, Knowledge of TEM.

Eye care-related factors: Distance from eye care service, Health insurance availability, time of presentation, History of MEM use.

Environmental factors: Availability of THs.

Operational Definition

Attitude towards TEM use: The total score was added up and a mean value was calculated. Participants who score the mean and greater than the mean were considered to have a good attitude towards TEM and participants who scored less than the mean were considered to have a poor attitude towards TEM.

Knowledge towards TEM: The total score was added up and a mean value was calculated. Participants who score the mean and greater than the mean were considered to have good knowledge about TEM and participants who scored less than the mean were considered as the ones who have poor knowledge regarding TEM.

Adult: Individuals with the age of 18 years and above.20

Available TH: Participants report the presence of at least one TH around their residence or town.

Has community leadership role: The participant who is/part of leaders of social/governmental organizations like “Edit”, “Ekub”, “Mahiber”, Elders, or Religious organizations.

Data Collection Procedures and Personnel

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews, using a standardized structured questionnaire containing information concerning socio-demographic characteristics, personal factors, eye care-related factors, and environmental factors. The questionnaire was prepared by reviewing related works of literature and scanning and considering the unique socio-cultural facts of the study population. The questionnaire was developed in English and then translated to Amharic and later translated back to English by language experts to ensure the accuracy and reliability of data. The interview was done by 5 trained optometrists.

Data Management and Analysis

Epi-info version 7 was used for data entry and every day at the end of data collection, every questionnaire was checked for completeness.

Data Quality Control

The Amharic translated version of the questionnaire was pretested at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar by taking 5% of the total sample size and necessary correction has been done based on the result. The questionnaire was translated from English to Amharic and then back to English to ensure accuracy, reliability, as well as consistency. The training was given to data collectors and supervisors for two days to make them familiar with their tasks. The principal investigator and supervisor had checked out the completeness, accuracy, and clarity of collected data on daily basis throughout the data collection period.

Data Processing and Analysis

At the time of data entry, the collected data was coded and checked for completeness, missing value, and clarity by the principal investigator and supervisor.

The coded data were entered to Epi Info 7 and exported to, processed, and analyzed by using SPSS version 20. The analysis was done by the investigator using the same computer package. Frequency and cross-tabulations were used for descriptive analysis of data.

An adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used to measure the strength of association between outcome and explanatory variables.

Association between dependent and independent variables was analyzed by a binary logistic regression model. Model fitness was checked using the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and the result of its p-value was 0.437. Bivariable logistic regression of variables with a P-value of <0.2 was entered into multivariable analysis and those with the value of p <0.05 were taken as statistically significant. The final result was presented using tables, figures, and graphs accordingly.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Medicine ethical review committee, before the data collection started. The ethical approval for verbal informed consent was obtained with a paper of Reference No 1992/05/20 from the ethical committee of the school. Full right to withdraw or refuse to participate in the study was respected. The study was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki.

Respondent’s data was collected without an identifier and confidentiality was maintained by locking it with a password.

Results

In this study, a total of 417 study participants gave valid and complete responses (response rate of 98.8%).

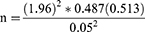

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Study Participants

The median age of the study participants was 37 with a range of 18–90 years. Among 417 eligible study participants, more than half of the participants were male 59.7% (249) (Table 2).

Attitude Towards Traditional Eye Medicine

From 417 total study participants, 60.7% (253) (95% CI: 19–26%) had good attitude regarding TEM. Among those who had a good attitude, above one-third 36.6% (41) had no any form of education so far and above half 56.1% (142) were male, 50.6% (128) were rural residents, 54.2% (137) were currently married and 51% (129) had poor knowledge about TEM (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Distribution of Attitude Towards TEM in Study Participants Among Adult Ophthalmic Patients Attending UoGCSH-CECTC, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021 (n=417) |

Factors Associated with Attitude Towards TEM

From the bivariable logistic regression analysis, age, sex, residence, occupation, educational status, average family monthly income, family history of TEM use, availability of TH, distance from eye care service, and time of presentation were selected and fitted into a multivariable logistic regression. On a multivariable logistic regression analysis residence, family history of TEM use, and availability of TH were found to be statistically significantly associated with attitude towards TEM.

To start from residence, the study participants living in rural areas were 6.46 times (AOR=6.46 (95% CI: 2.89–14.45)) more likely to have a good attitude towards TEM as compared to those residing in urban.

The odds of positive attitude towards TEM were 8 times (AOR=8.01 (95% CI: 4.17–15.37)) higher in study subjects with a positive family history of TEM use as compared to those who had no family history of TEM use.

Regarding TH availability, study participants who live in an area where traditional healers exist were 19.43 times (AOR=19.43 (95% CI: 12.06–31.64)) more likely to have a good attitude towards TEM than those who live in an area where traditional healers do not exist (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Factors Associated with Attitude Towards Traditional Eye Medicine Among Adult Ophthalmic Patients Attending UoGCSH-CECTC, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021 (n=114) |

Discussion

A positive attitude towards traditional eye medicine among adult ophthalmic patients attending UoGCSH-TECTC was (60.7%) (95% CI: 19–26%). This result was similar to a study conducted in China (63%).21

The result found in this study was lower than shreds evidence from Iran (75%),22 Singapore (92%),23 Hong Kong (97%),24 Eritrea (81%),25 and Shopa Bultum, Ethiopia (92%).26 This difference could be because of variation in the study setting. Those studies were conducted among hospital health care staff, medical students, and nurses, respectively.27,28 Besides, the higher familiarity of TM practice in a rural community like adults in Shopa Bultum could make the attitude positive.

On the other hand, this result was higher than the studies from Iran (5% and 13%)29,30 and Ethiopia 28.3%,31 38.8%,4 and 48.7%.9 It could be due to cultural, health status, and socioeconomic variation. This study was conducted on patients which concluded that a good attitude was discovered in the community exposed to TEM practice.

The rural residence had a significant association with a good attitude towards TEM. Many people in rural areas believe that diseases are caused by breaking taboos or not conforming to traditional societal rules, which led them to consult TH and had a positive attitude towards TEM.12,32

On the other hand, positive family history of TEM use had a positive association with a good attitude towards TEM. This was consistent with the studies conducted in Malaysia,33 Uganda,34 and Ethiopia.9 Considering TEM use as a trend and passing it from parents to children to treat abnormal eye conditions and respecting the saw of older members of the community who carry a high level of respect might be accountable for having a positive attitude towards TEM.12,35

Furthermore, the odds of a good attitude towards TEM were higher among study subjects living in TH available area than those who live in the area where TH did not exist. This was per the studies from India,19 Nigeria,36,37 and Ethiopia.9 The possible explanation for this might be due to direct or indirect influence and promotion done by traditional healers. Those individuals living around traditional healers might have an increased level of exposure to TEM-related practice. This could create a great opportunity to have a good attitude toward TEM and appreciate the activity of traditional healers.9

Limitation of the Study

It is known that patients tend to hide information they know causing social desirability bias. Due to the pandemic (COVID-19), patients with low income and from very remote areas may not come to the hospital that potentially causes selection bias.

Conclusion

Most adult ophthalmic patients had a positive attitude towards traditional eye medicine. Residing in rural area, availability of TH, and positive family history of TEM use had a positive significant association with a good attitude towards TEM. Educating the traditional healers on safe practices is crucial in reducing the burden.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest for this work to declare.

References

1. World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. World Health Organization; 2013.

2. Digban DK, Enitan SS, Otuneme OG, Adama S. Hormonal profile of women of reproductive age investigated for infertility in Bida Metropolis, Niger State, Nigeria. Sch J Appl Med Sci. 2017;5(5A):1750–1757.

3. Baylor J. Analysis of Traditional Medicine in Zanzibar, Tanzania; 2015.

4. Mohammed AY, Kasso M, Demeke A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of community on traditional medicine in Jara Town, Bale Zone South East Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2016;4(3):241. doi:10.11648/j.sjph.20160403.23

5. Kassaye KD, Amberbir A, Getachew B, Mussema Y. A historical overview of traditional medicine practices and policy in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;20(2):127–134.

6. Nyathirombo A, Mwesigye F, Mwaka A. Traditional eye health practices in Atyak Sub-county, Nebbi district-Uganda. J Ophthalmol East, Cent South Afr. 2013;16(1):63.

7. Mselle J. Visual impact of using traditional medicine on the injured eye in Africa. Acta Trop. 1998;70(2):185–192. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(98)00008-4

8. Sitotaw M. Understanding the role of traditional health in eye health care in Gurage Zone, Southern Ethiopia. York University, Canada; 2018.

9. Munaw MB, Assefa NL, Anbesse DH, Mulusew Tegegne M. Practice and associated factors among adult residents towards traditional eye medicine in Gondar City, North West Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. 2020;2020. doi:10.1155/2020/3548204

10. Koné WM, Atindehou KK, Terreaux C, Hostettmann K, Traoré D, Dosso M. Traditional medicine in north Côte-d’Ivoire: screening of 50 medicinal plants for antibacterial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93(1):43–49. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.006

11. Foster A, Johnson GG. Traditional eye medicines–good or bad news? Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78(11):807. doi:10.1136/bjo.78.11.807

12. Rashid S. Heritage, ethno-medicine and traditional medical practices in Bangladesh: an Anthropological Study; 2017. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348558646_Heritage_Ethno-medicine_and_Traditional_Medical_Practices_in_Bangladesh. Accessed November 23, 2021.

13. Yorston D, Foster A. Traditional eye medicines and corneal ulceration in Tanzania. J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;97(4):211–214.

14. Nyenze E, Ilako D, Karimurio J. KAP of traditional healers on the treatment of eye diseases in Kitui district of Kenya. East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2007;41(2–4):161–209.

15. Omar R, Aziz J. Low vision rehabilitation can improve quality of life. Jurnal Kebajikan Masyarakat. 2010;36:99–110.

16. James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, Adams J. Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(5):e000895. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895

17. Chitindingu E, George G, Gow J. A review of the integration of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine into the curriculum of South African medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-40

18. Rahmatullah M, Ishika T, Rahman M, et al. Plants prescribed for both preventive and therapeutic purposes by the traditional healers of the Bede community residing by the Turag River, Dhaka district. Am Eurasian J Sustain Agric. 2011;5:325–331.

19. World Health Organization. Traditional medicine in Asia: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2002.

20. Petry NM. A comparison of young, middle-aged, and older adult treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Gerontologist. 2002;42(1):92–99. doi:10.1093/geront/42.1.92

21. Koh HL, Teo HH, Ng HL. Pharmacists’ patterns of use, knowledge, and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9(1):51–63. doi:10.1089/107555303321222946

22. Adib-Hajbaghery M, Hoseinian M. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward complementary and traditional medicine among Kashan health care staff, 2012. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(1):126–132. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.009

23. Yeo AS, Yeo JC, Yeo C, Lee CH, Lim LF, Lee TL. Perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine amongst medical students in Singapore–a survey. Acupuncture Med. 2005;23(1):19–26. doi:10.1136/aim.23.1.19

24. Holroyd E, Zhang AL, Suen LK, Xue CC. Beliefs and attitudes towards complementary medicine among registered nurses in Hong Kong. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(11):1660–1666. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.04.003

25. Tesfamariam S, Tesfai F, Hussien L, et al. Traditional medicine among the community of Gash-Barka region, Eritrea: attitude, societal dependence, and pattern of use. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12906-021-03247-9

26. Gari A, Yarlagadda R, Wolde-Mariam M. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and management of traditional medicine among people of Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(2):136. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.148782

27. Alkharfy K. Community pharmacists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices towards herbal remedies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. EMHJ. 2010;16(9):988–993. doi:10.26719/2010.16.9.988

28. Al Saeedi M, El Zubier A, Bahnassi A, Al Dawood K. Patterns of belief and use of traditional remedies by diabetic patients in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. EMHJ. 2003;9(1–2):99–107. doi:10.26719/2003.9.1-2.99

29. Sayadi A, Rezaeian M, Shabani Z. The knowledge and attitude of medical students of Rafsanjan University of medical sciences about complementary and alternative medicine, 2010. Sci Res Essays. 2011;6:5192–5196.

30. Mirgai V, Saisai AR, Heydarinasab M. Knowledge and attitude of Rafsanjan physicians about complementary and alternative medicine. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2011;13:06.

31. Wassie SM, Aragie LL, Taye BW, Mekonnen LB. Knowledge, attitude, and utilization of traditional medicine among the communities of Merawi town, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015. doi:10.1155/2015/138073.

32. Ukponmwan CU, Momoh N. Incidence and complications of traditional eye medications in Nigeria in a teaching hospital. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2010;17(4):315. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.71596

33. Rahman AA, Sulaiman SA, Ahmad Z, Salleh H, Daud NW, Hamid AM. Women’s attitude and sociodemographic characteristics influencing usage of herbal medicines during pregnancy in Tumpat District, Kelantan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(2):330.

34. Atwine F, Hultsjö S, Albin B, Hjelm K. Health-care seeking behavior and the use of traditional medicine among persons with type 2 diabetes in south-western Uganda: a study of focus group interviews. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20(1). doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.76.5497

35. Jahan FI, Hasan MRU, Jahan R, et al. A comparison of medicinal plant usage by folk medicinal practitioners of two adjoining villages in Lalmonirhat district, Bangladesh. Am Eurasian J Sustain Agric. 2011;5(1):46–66.

36. Adepoju G. The attitudes and perceptions of urban and rural dwellers to traditional medical practice in Nigeria: a comparative analysis. Int J Gender Health Stud. 2005;3(1):190–191.

37. Aluko T. Trading in traditional medicine: the challenges for womanhood and the health care system in Nigeria. Int J Gender Health Stud. 2005;2(1):47–54.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.