Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 14

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and impulsivity in female patients with fibromyalgia

Received 8 December 2017

Accepted for publication 31 May 2018

Published 24 July 2018 Volume 2018:14 Pages 1883—1889

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S159312

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Ertan Yılmaz,1 Lut Tamam2

1Department of Psychiatry, Ceyhan State Hospital, Adana, Turkey; 2Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey

Objective: Data which indicate a greater role of the central nervous system in the etiology of fibromyalgia are increasing. The goal of the present study is to determine the link between fibromyalgia and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and, in addition, to reveal the relevance of impulsivity dimension.

Methods: The study included 78 females with fibromyalgia who applied to a physical medicine and rehabilitation polyclinic in Ceyhan State Hospital and 54 healthy females. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was made by an experienced specialist of physical medicine and rehabilitation based on the American Rheumatology Association Diagnostic Criteria (2010). The diagnosis of ADHD was by an experienced psychiatrist using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5. The following inventories were used: adult ADHD self-report scale, Wender Utah rating scale, and Barratt impulsivity scale short form.

Results: Adult ADHD was detected in 29.5% of the fibromyalgia group and 7.4% of the control group; childhood and adolescent attention hyperactivity disorder ratios in these groups were 33.3% and 11.1%, respectively. The differences were statistically significant (P=0.002, P=0.003). Scores of the fibromyalgia group on the Wender Utah rating scale, adult ADHD self-report scale, attention subscale, hyperactivity–impulsivity subscale, and the Barratt impulsivity scale for non-planning and attentional impulsivity were found to be significantly higher than the control group (P<0.05, P<0.01, P<0.01, P<0.05, P<0.01, P<0.05, respectively).

Conclusion: The present study has shown that both adult and childhood ADHD are quite common in female fibromyalgia patients. There was a link between fibromyalgia and impulsivity. Certain subtypes of fibromyalgia and attention-deficit hyperactivity deficit disorder could be sharing the common etiological pathways.

Keywords: attention, fibromyalgia, hyperactivity, impulsivity

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (or fibromyalgia syndrome-FMS) is a common disorder of the musculoskeletal system. Along with widespread joint and muscle pain, fatigue, restless sleep, and cognitive findings may be seen.1 Its frequency of occurrence in the population is 2%–5%, and it occurs mostly in women.2,3

The etiology of fibromyalgia has not been completely elucidated.4 However, the data indicating a greater role of central nervous system (CNS) in the etiology of fibromyalgia are increasing.5 Restless leg syndrome, which is characteristic of disorder of the dopaminergic system, is very common in fibromyalgia patients.6 Studies have found that duloxetine, an antidepressant acting on serotonin and norepinephrine, pregabalin acting on GABA, and the dopamine agonist pramipexole are effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia.7–9

In fibromyalgia patients, dysfunctions with losses of memory and in various cognitive fields known as fibrofog are seen.10,11 It is a disorder with cognitive deficits similar to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Impairments are seen in many cognitive areas including concentration, attention span, and working memory.12 Attention deficit and hyperactivity/impulsivity are subtypes of ADHD.13 It has been suggested in animal studies that serotonin along with norepinephrine and dopamine contribute to the etiology of ADHD.14,15

In a study by Golimstok et al, it was found that fibromyalgia was common in individuals with ADHD.16

In the light of this information, various common features of the two illnesses can be listed as follows: 1) as well as ADHD being a disorder of the CNS, there is increasing evidence of a connection between fibromyalgia and the CNS; 2) there are data indicating that similar neurotransmitter pathways (norepinephrine and dopamine) play a key role in the etiology of both disorders; 3) cognitive symptoms are an important clinical part of both conditions; and 4) there are case studies showing that atomoxetine treatment, of proven effectiveness with ADHD, is also effective with pain related to fibromyalgia.17

There are a few studies of the relationship of fibromyalgia with impulsivity. In a study by Montoro and Reyes del Paso based on the Eysenck personality model, the psychotism dimension including impulsivity was found to be high in the fibromyalgia group.18

The goal of the present study is to determine the link between fibromyalgia and ADHD, as well as to investigate the relevance of impulsivity dimension in this possible relationship.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted between June 2015 and June 2016 at Ceyhan State Hospital, Adana. Permission was obtained from the ethics committee of Adana Numune Training and Research Hospital. A written informed consent form was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the evaluation. Participants were divided into two groups, a fibromyalgia group and a control group. The study group included 78 females with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia who applied to physical medicine and rehabilitation outpatient clinics in Ceyhan State Hospital. The control group consisted of 54 healthy female volunteers who were recruited with local newspaper ads from the same region. The study group and the healthy volunteers were evaluated by the same psychiatrist (EY) to find out the diagnosis of childhood and adult ADHD.

Diagnosis of fibromyalgia

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was given by physical examination and investigation based on the 2010 criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).1 These criteria were as follows:

- a widespread pain index (WPI) ≥7 and symptom severity (SS) scale score of ≥5; or WPI of 3–6 and SS scale score of >9;

- the symptoms should be present at a similar level for at least three months; and

- another disorder that would otherwise explain the pain should be excluded.

Diagnosis of ADHD

Diagnosis of adult ADHD was given on the basis of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria developed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). To receive a diagnosis of adult ADHD, a patient has to fulfill at least five of nine criteria relating to attention deficit and/or at least five of nine criteria relating to hyperactivity and impulsivity, have symptoms appearing before the age of 12, have symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity occurring in two or more function areas, have clear evidence that symptoms have impaired social or school or work-related function or that function quality has fallen, and symptoms not better explained by another medical or mental illness.19

Childhood ADHD was diagnosed based on APA DSM-5 criteria according to information taken from the participants themselves, supported by the patient’s family or other persons who could provide information if they could be reached. The conditions required were having at least six of nine criteria relating to attention and/or at least six of nine criteria relating to hyperactivity and impulsivity, the symptoms continuing for at least 6 months, no expression of oppositional behavior, defiance, hostility, or a failure to understand tasks or instructions in at least two function areas, and clear evidence of a decline or breakdown in functionality.19

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The presence of childhood ADHD is essential for the diagnosis of adult ADHD. In order to reduce failures inherent to remembrance of childhood memories, participants were selected were between 18 and 55 years of age. All participants were female. People whose education levels were sufficient to complete the forms were included in the study. Anyone with a mental illness at a level that could hinder the evaluation, such as mental retardation, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorders, was excluded from the study.

Evaluation scales

Sociodemographic form

This form was developed by the researchers and included questions on current age, marital status, employment, duration of education (years), and participants’ alcohol consumption and smoking status, and previous suicide attempts, previous (childhood) and current diagnosis of ADHD, or previous and present diagnosis of a comorbid physical illness. Psychiatric and physical illness and previous suicide history were primarily based on self-report of cases and psychiatric examination conducted on site. Information provided by the patients was checked with other accessible sources, such as living parents or siblings, spouses, and available medical files. For statistical purpose, patients with mid and high socioeconomic status were treated as one group while patients who had been divorced or never married were grouped as single and housewives; and students and retired patients were grouped as unemployed.

Adult ADHD self-reporting scale (ASRS)

The ASRS is a scanning scale developed by the World Health Organization.20 It has two subscales with nine questions each on attention deficit and hyperactivity and impulsivity. The questions are intended to determine how often each symptom has appeared in the previous six months with a score between 0 and 4. The “not at all” choice scores 0, “rarely” 1, “occasionally” 2, “often” 3, and “very often” scores 4. Validity and reliability of Turkish version of the scale was performed by Dogan et al.21

Wender Utah rating scale (WURS)

The WURS was developed to inquire retrospectively into symptoms of ADHD in childhood and to help to diagnose ADHD in adults.22 Adults with ADHD are scored with 25 items that were found to discriminate best from healthy controls. It is a five-point Likert type self-reporting scale. The total WURS score is between 0 and 100. Turkish validity and reliability were performed by Oncü et al.23

Short form of Barratt impulsiveness scale (BIS-11-SF)

The Barratt impulsiveness scale, initially developed by Barratt in 1959, was developed into its final form in 1995.24 BIS-11-SF is a self-reporting scale with 15 items, evaluating the appearance of impulsivity. Items are scored with a 4-way Likert-type scale where 1 indicates seldom/never; 2, sometimes; 3, often; and 4, almost always/always. It has three reliable and non-overlapping subscales of not planning, motor impulsiveness, and attention impulsiveness. High BIS values indicate higher levels of impulsivity. Validity and reliability study of Turkish version of the BIS-11-SF was carried out by Tamam et al.25

Visual analog scale

This was used to evaluate the severity of pain. It consists of a 10 cm horizontal line. The point marked by the patient is recorded. 0 is taken as no pain and 10 as the most unbearable pain.26

Procedure

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was determined by two different experienced physical medicine and rehabilitation experts based on 2010 ACR criteria.1 After confirmation of their diagnosis of fibromyalgia, the individuals were referred to a psychiatrist. Diagnosis of childhood and adult ADHD and the scales (WURS, ASRS, BIS-11-SF, and VAS) were applied by an experienced psychiatrist. For a diagnosis of ADHD, it was required that the DSM-5 criteria were completely met. Eight of the 114 subjects sent to the psychiatrist with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia for this purpose were excluded from the study because their education level was too low for them to complete the scale, seven were excluded because of mental or physical illness, 10 subjects were excluded since they did not accept the conditions of study, and 11 subjects due to insufficient information they provided in scales they completed.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the program IBM SPSS-23. The independent samples t-test was used for the comparison of parametric continuous variables (ie, age, psychometric test scores, duration of illness, and education) between fibromyalgia and control groups. The chi-squared test was used to analyze categorical variables (ie, marital status, ADHD rates). In the analyses of categorical variables in 2×2 tables, if 20% of the cells in the cross-tabulation have an expected frequency of 5, or if any cell count is 1, we used Fisher’s exact test to report relevant results.

Results

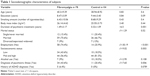

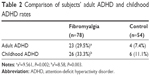

The fibromyalgia group included 78 (59%) participants, and the control group included 54 (41%). The mean age of the fibromyalgia group was 40.3±9.39 years and that of the control group 38.9±8.92 years. No statistically significant difference was found between two groups in terms of age, education level, and marital status (Table 1). ADHD was detected in 29.5% (n=23) of the fibromyalgia group, and 7.4% (n=4) of the control group; childhood and adolescent ADHD ratios were 33.3% (n=26) and 11.1% (n=6), respectively. These differences were statistically significant (P=0.002 and P=0.003) (Table 2).

| Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of subjects |

| Table 2 Comparison of subjects’ adult ADHD and childhood ADHD rates |

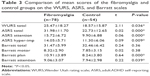

The scores of the study group on WURS, ASRS, the attention and hyperactivity–impulsivity subscales of the ASRS scale, and the non-planning and attentional impulsivity subscales of BIS-11-SF were found to be significantly higher than those of the control group (P=0.036, P<0.01, P<0.01, P=0.009, P<0.01, and P=0.039, respectively) (Table 3).

The fibromyalgia group had a significantly higher rate of diagnosis of psychiatric illness than the control group (43.6%, and 20.4%, respectively: x2=7.65, P=0.006). The duration of psychiatric treatment in the past was also significantly higher in the fibromyalgia group (1.49±3.17 years vs 0.32±1.09 years; t=16.54, P=0.001). Comparing the two groups in terms of previous diagnosis of ADHD, it was found that no subject in the control group had been diagnosed with ADHD, while 6.4% of subjects in the fibromyalgia group had been diagnosed with ADHD (Fisher’s exact test, P=0.078) (Table 1).

In the fibromyalgia group, a comparison was made of the duration of fibromyalgia and scores on the VAS of the two subgroups of those with and without a diagnosis of ADHD, and no significant difference was found (t=0.75, P=0.38 for VAS, and t=0.78, P=0.37 for duration of fibromyalgia).

Discussion

Previous studies exist searching for childhood ADHD in women with fibromyalgia and on the frequency of fibromyalgia in patients with ADHD.16,27 In the present study, the relationships of fibromyalgia not only with adult ADHD but also with childhood ADHD were investigated using both DSM-5 diagnostic measures and scales. The relationship between fibromyalgia and impulsivity was also investigated.

In the general population, the frequency of childhood ADHD is ~5.9%–7.1%.29 In the present study, however, the frequency of childhood ADHD according to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria was found to be 33.3% in the fibromyalgia group and 11.1% in the control group. These findings are quite similar to those of a recent study conducted with 201 female patients with fibromyalgia and 198 age-matched healthy women by Reyero et al (32.3% in patient with fibromyalgia, 2.52% in control cases), indicating a possible common comorbidity.27

In a meta-analysis study reviewing the population studies on adults, frequency of ADHD was found to be 2.5%, and in an American sample the frequency was 4.4%.30,31 In our study, the frequency of adult ADHD in the fibromyalgia group was 29.5% and 7.4% in the control group. In a study conducted in Holland on a clinical sample without a control group, the frequency of adult ADHD in patients with fibromyalgia was similar to that in our study (25%).28 The diagnosis of childhood ADHD in our study was given retrospectively, and it was found that 66.6% of those had been diagnosed with ADHD still had the same disorder in adulthood. This result is consistent with literature reports that the disorder continues into adulthood in approximately two-thirds of cases.32,33 In our results, it was found that the frequency of ADHD in fibromyalgia patients was distinctly higher than in the controls. We may speculate that fibromyalgia is not an illness of a totally homogeneous group, and at least one subgroup may share the same etiological basis with ADHD. As explained before, the two disorders have the same cognitive problems and similar neurotransmitter abnormalities, and there is evidence that the CNS plays a basic role in both. This may indicate a relationship between these disorders.9–12,14,15

Total scores obtained from WURS in our study were higher in the fibromyalgia group, similar to the study by Reyero et al.27 Moreover, in another study with a comparatively small number of subjects, total mean scores obtained from WURS in a fibromyalgia group were higher than those from an ADHD group.34

The fibromyalgia group had significantly higher ASRS total, attention, and hyperactivity/impulsivity score than the control group, suggesting higher presence of ADHD features.

In the evaluation of impulsivity with BIS-11-SF, the two groups were significantly different in terms of the subscales of not planning and attention impulsivity. No significant difference was found on the basis of Barratt total scores and scores on the subscale of motor impulsivity. In a factor analysis by Patton et al using BIS, motor impulsivity was described as acting without thinking, non-planning was characterized as a focusing on the present or a lack of future-planning, and cognitive impulsiveness as making quick decisions.24 In another study using BIS, it has been demonstrated that impulsivity was related to the psychoticism dimension of Eysenck’s Personality Questionnaire (EPQ).35 In a study of the relationship between fibromyalgia and personality characteristics by Montoro et al, a significant increase was noted in the psychoticism dimension of EPQ.18 Bucourt et al also obtained a similar result.36

This is a subject of potential importance since these results show a link between fibromyalgia and symptom clusters of hyperactivity–impulsivity. Several studies in the literature also suggested that ADHD, FMS, and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) might have common features. Likewise, Young and Redmond reported a number of adult patients who presented primarily with symptoms of ADHD, predominantly inattentive type, to an outpatient psychiatric clinic and had unexplained fatigue, widespread musculoskeletal pain, or a pre-existing diagnosis of CFS or FMS.37

In our study, approximately one-third of the fibromyalgia group had a diagnosis of ADHD. A future research topic could be whether the fibromyalgia impulsivity relationship comes from comorbidity with ADHD or is a component of fibromyalgia independently. The proportion of those in the fibromyalgia group who had received psychiatric treatment in the past and the duration of their treatment were higher than in the control group. This finding is not surprising in the light of previous studies that have found high comorbidity with fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders, which were predominantly anxiety and depressive disorders.38,39

Fibromyalgia is widely recognized as a “stress-related” disorder due to its frequent onset and apparent exacerbation of its symptoms in presence of stressful events.40 Dysfunction of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis strongly suggests that early-life stress or severe or prolonged stress effectively predicts the development of chronic and severe pain.41

High frequency of both childhood and adult ADHD among fibromyalgia patients suggests that ADHD could be a predictor of the development of fibromyalgia in the future.

Considering the childhood and adulthood period of the fibromyalgia patients in light of these data, it may be suggested that not only the subdimension of attention deficit but also the subdimension of hyperactivity/impulsivity in ADHD are important and should be carefully assessed. Paying attention to ADHD in the treatment of fibromyalgia may deliver desirable clinical outcomes.42

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, all the research subjects were female. Secondly, the assessment of childhood ADHD was conducted largely on information obtained from the subjects themselves. This may be affected by lapses of memory. Thirdly, the number of subjects included in the study was relatively small. Fourthly, fibromyalgia diagnosis was drawn from the 2010 ACR criteria.22 The diagnosis of fibromyalgia was renewed by ACR in 2016,43 but we were well into the study at that time.

However, the diagnosis of ADHD was given not on the basis of a scale but on the basis of a clinical interview by a psychiatrist. Scale based ADHD assessment included both adulthood and childhood. There are several studies of the relationship between fibromyalgia and personality characteristics, but the relationship between fibromyalgia and impulsivity has not been sufficiently addressed, and so our findings may help guide future studies.

Acknowledgment

The abstract was presented at the 9th International Congress on Psychopharmacology & 5th International Symposium on Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology in Antalya, Turkey, April 26–30, 2017.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest and the work was not supported or funded by any drug company.

References

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(5):600–610. | ||

Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):19–28. | ||

Yunus MB. Gender differences in fibromyalgia and other related syndromes. J Gend Specif Med. 2002;5(2):42–47. | ||

Nampiaparampil DE, Shmerling RH. A review of fibromyalgia. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 1):794–800. | ||

Schweinhardt P, Sauro KM, Bushnell MC. Fibromyalgia: a disorder of the brain? Neuroscientist. 2008;14(5):415–421. | ||

Yunus MB, Aldag JC. Restless legs syndrome and leg cramps in fibromyalgia syndrome: a controlled study. BMJ. 1996;312(7042):1339. | ||

Arnold LM, Lu Y, Crofford LJ, et al. A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(9):2974–2984. | ||

Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1264–1273. | ||

Holman AJ, Myers RR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, in patients with fibromyalgia receiving concomitant medications. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2495–2505. | ||

Kravitz HM, Katz RS. Fibrofog and fibromyalgia: a narrative review and implications for clinical practice. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(7):1115–1125. | ||

Gelonch O, Garolera M, Valls J, Rosselló L, Pifarré J. Executive function in fibromyalgia: comparing subjective and objective measures. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;66:113–122. | ||

Mostert JC, Onnink AMH, Klein M, et al. Cognitive heterogeneity in adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic analysis of neuropsychological measurements. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(11):2062–2074. | ||

Thapar A, Cooper M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1240–1250. | ||

Russell VA. Overview of animal models of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2011;54(1):9.35.1–9.35.9. | ||

Arnsten AF, Pliszka SR. Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):211–216. | ||

Golimstok A, Fernandez MC, Garcia Basalo MM, et al. Adult attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder and fibromyalgia: a case-control study. Neuro Open J. 2015;2:61–66. | ||

Vorobeychik Y, Acquadro MA. Use of atomoxetine in a patient with fibromyalgia syndrome and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2008;16(3):189–192. | ||

Montoro CI, Reyes del Paso GA. Personality and fibromyalgia: relationships with clinical, emotional, and functional variables. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;85:236–244. | ||

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM-5. 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. | ||

Adler LA, Spencer T, Faraone SV, et al. Validity of pilot Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) to Rate Adult ADHD symptoms. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18(3):145–148. | ||

Dogan S, Oncü B, Saracoglu GV, Kücükgöncü S. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1). Anatolian J Psychiatry. 2009;10:77–87. | ||

Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(6):885–890. | ||

Oncü B, Olmez S, Sentürk V. Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Wender Utah Rating Scale for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2005;16(4):252–259. | ||

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. | ||

Tamam L, Gulec H, Karatas G. Short Form of Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11-SF) Turkish Adaptation Study. Neuropsychiatry Ars. 2013;50:130–134. | ||

Revill SI, Robinson JO, Rosen M, Hogg MI. The reliability of a linear analogue for evaluating pain. Anaesthesia. 1976;31(9):1191–1198. | ||

Reyero F, Ponce G, Rodriguez-Jimenez R, et al. High frequency of childhood ADHD history in women with fibromyalgia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(8):482–483. | ||

Derksen MT, Vreeling MJ, Tchetverikov I. High frequency of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among fibromyalgia patients in the Netherlands: should a systematic collaboration between rheumatologists and psychiatrists be sought? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(Suppl 88):141. | ||

Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):490–499. | ||

Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204–211. | ||

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–723. | ||

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):159–165. | ||

Kooij SJ, Bejerot S, Blackwell A, et al. European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:67. | ||

Krause K-H, Krause J, Magyarosy I, Ernst E, Pongratz D. Fibromyalgia syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: is there a comorbidity and are there consequences for the therapy of fibromyalgia syndrome? J Musculoskelet Pain. 1998;6(4):111–116. | ||

O’Boyle M, Barratt ES. Impulsivity and DSM-III-R personality disorders. Pers Individ Dif. 1993;14(4):609–611. | ||

Bucourt E, Martaillé V, Mulleman D, et al. Comparison of the Big Five personality traits in fibromyalgia and other rheumatic diseases. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84(2):203–207. | ||

Young JL, Redmond JC, Fibromyalgia RJC. Fibromylagia, chronic fatigue, and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in the adult: a case study. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40(1):118–126. | ||

Thieme K, Turk DC, Flor H. Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationship to somatic and psychosocial variables. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):837–844. | ||

Fietta P, Fietta P, Manganelli P. Fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders. Acta Biomed. 2007;78(2):88–95. | ||

Clauw DJ, Crofford LJ. Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: what we know, and what we need to know. Best Pract Res Clin Rheum. 2003;17(4):685–701. | ||

McBeth J, Silman AJ, Gupta A, Chiu YH, Ray D, Morriss R, et al. Moderation of psychosocial risk factors through dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis in the onset of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain: findings of a population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007:56:360–371. | ||

van Rensburg R, Meyer HP, Hitchcock SA, Schuler CE. Screening for Adult ADHD in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain Med. Epub 2017 Nov 1. | ||

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. 2016 revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(3):319–329. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.