Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 12

Assessing Building Blocks for Patient Safety Culture—a Quantitative Assessment of Saudi Arabia

Authors Alrowely Z, Ghazi Baker O

Received 13 July 2019

Accepted for publication 9 November 2019

Published 6 December 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 275—285

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S223097

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Marco Carotenuto

Zeid Alrowely, 1 Omar Ghazi Baker 2

1Health Investment Development Administration, Directorate of Health Affairs, Aljouf, Saudi Arabia; 2College of Nursing, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Zeid Alrowely

Health Investment Development Administration, Directorate of Health Affairs, Aljouf, Saudi Arabia

Tel +966 50 339 9488

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The study analyzes staffs’ perception of a safety culture and their knowledge of safety measures in the hospitals of Saudi Arabia.

Patients and methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted by considering six different public hospitals from Arar city, and by recruiting 503 nurses. Building blocks of patient safety culture were measured through survey questions.

Results: The highest positive rating (81%) was received by both “people support one another in this unit” and “in this unit, people treat each other with respect.” Supervisor/manager expectations and actions promoting patient safety was rated neutrally (n = 283; 56%) with an average mean score of 3.17± 0.50, which suggested a neutral response by participants. Organizational learning, along with continuous improvement, was positively rated (n = 406; 81%) with an average mean score of 3.93± 0.61.

Conclusion: It demonstrated that participant nurses neither disagree nor agree on the level of patient safety culture prevailing in their hospital setting.

Keywords: nurses, safety management, perception, environment

Corrigendum for this paper has been published

Introduction

The building block refers to the elements which help deliver safe patient care. One of the most sublime building blocks of patient safety in healthcare organizations is organizational culture. Several attempts have been made in different countries to focus on the evaluation of the safety culture.1–3 Building blocks of safety culture are associated to assorted healthcare consequences, which include nurse back injuries, patient satisfaction, urinary tract infections, medication errors, and perceptions of patients toward the nurse responsiveness, and nurse satisfaction.4 It is deemed that unintentional errors, mistakes, and safety violates increase safety problems. Previously, studies have shown that a complex chain of events leads to the majority of errors and adverse events more accurately.5,6 Thereby, patient safety is rooted in the reduction and prevention of adverse consequences or injuries in patient safety movement.7

The inbound relationship between culture and climate possesses different approaches to measure the same phenomenon. There are multiple and various definitions of organizational culture, but they are generally characterized as the shared norms, tacit assumptions, and values of individuals within the organization.8 In contrast, other organizations involve social capacities and practices to define organizational culture. Thereby, safety climate is characterized as shared perceptions about the practices, processes, and events and the behavior that is supported, anticipated, and rewarded in a specific organizational setting.9 Earlier, blame-free environment for reporting, organizational resources for safety, identification of the risk of error in the organizational activities, and collaboration across the organization were identified.10 To provide a foundation for safer performance, the development of effective safety practices and consideration of these practices is associated with an overall safety climate.

Appropriate assessment of patient safety culture is confined to the competence to define the safe cultural practices. Thereby, the need for comparatively quick, easy-to-use, and low-cost assessments of patient safety culture has rooted reliance on patient safety climate survey.11 At a specific point of consideration, patient safety climate demonstrates employee attitudes and perceptions regarding the surface features of patient safety culture. It has been deemed that a positive patient safety culture is associated with improved patient safety.12 Thereby, focusing practice change via patient safety climate is attributed as a fundamental strategy to improve and strengthen patient safety and consequences in a hospital setting.

In the recent era, nursing scholars are confronted to evaluate the perspectives of nursing on a safety culture that can deter inadequate events and injuries to patients. A patient safety culture should be stimulated, which modifies the social context from an untrusting blame approach to a trusting approach that stimulates healthcare staff for sharing information regarding safety issues and the efforts made to encourage a safer healthcare environment.13 Several challenges might be faced by nursing practice associated with the integration of a safety culture and the conflict in the work environment. In addition, several other challenges have been unaddressed, such as inadequate management of patient care errors, lack of mutual trust among healthcare workers, overstressed feelings, lack of evidence of collaboration and teamwork, lack of clear communication, and conflict contribution to job satisfaction of nurses.14,15 Consequently, this impedes the ability to offer quality, humane, and safer care.

Additionally, the absence of safety culture for nurses has become a major dilemma for hospital administrators and nurse leaders and, thereby, they have become more cautious of the quality and safety of the staff work environment and its influence on the workforce.11 The nurse’s perceptions should be viewed critically to promote the current work environment and patient safety, which is not restricting the continuance efforts of healthcare agencies in preventing workplace conflict and bullying, provision of adequate and exceptional patient care, and increasing staff retention.7 An understanding of the criticalities of the issues in the workplace has been provided by previous studies such as the conflict in the workplace environment and the occurrence of these conflicts.2 However, there still lacks research on the staff perceptions of a safety culture and their knowledge of safety measures in Saudi Arabian hospitals.

Review of the past work in the Arab world derives the study further, such as Aljadhey et al16 emphasized that hospital management must instigate efforts for improving the nurse perception related to the patient safety culture. In the same context, Al-Awa et al17 demonstrated that accreditation has enhanced the registered nurses’ perception of patient safety concerning awareness of patient safety and care. Also, the increase in inpatient safety further needs a patient safety culture, which helps in deriving favorable health outcomes of the healthcare organization.18 Elmontsri et al19 have also emphasized the need to learn from the earlier medical errors for improving its recurrence. This necessitates the prioritization of the patient’s safety practices. Thereby, the study aimed to explore the building blocks of patient safety culture in Arar Hospitals in Saudi Arabia. This study is needed because of the scarcity of research on hospital personnel perceptions related to culture and knowledge of safety measures, despite various studies that are conducted internationally. It is also likely to help the staff nurses in developing an understanding of cultural practices in clinical setting.

This study will be of significant benefit as it provides a glimpse of the current standing of the patient safety culture in Saudi Hospitals. Firstly, this study assists the policymakers in utilizing the results when formulating policies and processes associated with total quality management. Secondly, administrators can use the results as a benchmark to strengthen, formulate, and implement strategies for creating a safety culture in their institutions. Thirdly, staff nurses can increase their conscious awareness of the need to develop and practice patient safety culture to generate nursing knowledge. Lastly, future researchers will be benefited from the results and will consider it as a benchmark for future intervention studies on patient safety culture nationally and internationally.

Materials and Methods

Design

A descriptive correlational and cross-sectional design has been used. The reason for selecting a cross-sectional survey was the group of participants, which was selected from a defined population of staff nurses employed at one point of time in different departments in six public hospitals in Arar, Saudi Arabia.

Participants

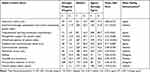

The accessible population in this study were nurses working in Arar City, Rafah City, and Turaif City Hospitals with at least 100 beds capacity. The participant nurses in this study were recruited from the public hospitals located in Saudi Arabia. However, a total of 690 participants were targeted based on quota sampling technique out of the total population of 1380 staff nurses. The response rate obtained was between 41% and 95%, with an overall response rate of 73% and a final total sample size of 503 (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Study Settings, Population, and Sample |

Setting

Six different public hospitals were selected from Arar city, which include Arar Central Hospital, Arar Maternity and Children Hospital, Prince Abdul-Aziz Bin Musaad Hospital, and AlAmal Complex for Mental Health; Rafah Central Hospital in Rafah City, and Turaif General Hospital in Turaif City. The selection of these hospitals was made due to the inclusion criteria set for hospitals with at least 100 beds capacity in the Northern Region. Further, the different hospital characteristics that might affect staff perceptions of safety culture have been controlled by recruiting the hospitals that compiled with the Ministry of Health General Directorate of Health Affairs guidelines.

Study Tool

The Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture by AHRQ publication has been used as a study tool in this study.20 Staff perceptions of patient safety culture’s building blocks were measured in the selected hospitals using the survey. Twelve building blocks of patient safety culture have been included with each dimension measured by three or four survey questions. The building blocks refer to the aspects which contribute significantly to the promotion of the safety culture. These are the areas of strength that understanding and right use can help optimize patients’ safety. The included building blocks in the study include teamwork, supervisor/manager expectations, and actions promoting patient safety, management support for patient safety, organizational learning–continuous improvement, overall perceptions of patient safety, staffing, teamwork across units, handoffs and transitions, and non-punitive response, communication openness, feedback and communication.

Nine components used the response categories demonstrated by the level of agreement and disagreement of the items in each component out of the 12 components. These components include teamwork within units with 4 item questions, supervisor/manager expectations, and actions promoting patient safety with 4 item questions, organizational learning–continuous improvement with item questions, and management support for patient safety with 3 item questions. In addition, these nine components included overall perceptions of patient safety with 4 item questions, teamwork across units with 4 item questions, staffing with 4 item questions, handoffs and transitions with 4 item questions, and non-punitive response to an error with 3 item questions. In addition, the 3 remaining components: communication openness with 3 item questions, feedback and communication about error with 3 item questions, and frequency of events reported with 3 item questions have the following response categories (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Most of the time, Always).

Validity and Reliability

The subscales of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture from AHRQ (2014) by Ulrich & Kear (2014) helped in testing the validity and reliability of the present study. The average value of Cronbach’s alpha for the components was 0.77.

Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 21.0. Descriptive statistics were applied to present demographic variables, whereas Pearson Correlation analysis was used to explore the association between independent and dependent variables. Multiple regression analysis was used to examine the influence of independent variables on the dependent variable.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at King Saud University and the Ministry of Health General Directorate of Health Affairs in the Northern Border Region to conduct the study in six different hospitals. Permission to use the instrument was obtained through electronic mail from Mr. David I. Lewin (AHRQ) dated 11 September 2015. The instruments were distributed to the hospital based on the corresponding target sample size across all nursing departments. A cover letter requesting for voluntary participation from the staff nurses, ensuring anonymity of identities, confidentiality of responses, and possible publication of the study was provided to participants. The participants were not provided with any form of compensation in their participation in the study. The inclusion criteria include: those in active full-time employment at the time data were gathered and willingness to voluntarily participate in the study. The only exclusion criterion was the non-willingness or refusal to voluntarily participate in the study. Participants were informed that the completion of the survey will be considered as evidence of consent to participate (considered informed consent).

Results

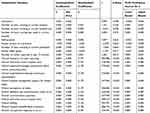

The demographic details of the participants were initially studied. Table 2 presents that most of the participants were from Arar Maternity and Children Hospital (n=148), Arar Central Hospital (n = 119) and Turaif General Hospital (n=83). Most of the participants were registered nurses (n=469) working in the current hospital from 1 to 5 years (n=195), followed by participants with less than 1 year (n=172). The majority of the participants had less than 1 year of experience in their current assigned unit (n=226), and worked majorly for 40–59 hrs per week (n=320), where only 47 had no patient interaction. Similarly, most of the nurses were assigned in the emergency unit and intensive care unit (n=75 and 71, respectively).

|

Table 2 Participants' Demographics |

Based on the scoring scale used in this study, the responses of the nurses were aggregated. The average rating of the dimensions was calculated by taking the average of the scores of all the items in each of the 12 dimensions. Tables 3 and 4 have illustrated the overall patient safety culture based on the average ratings. Overall response of agreement was suggested based on the response of 77.5% participant nurses, who rated overall teamwork units to be positive, along with an average mean score of 3.80+0.73. The highest positive rating (81%) was received by both “people support one another in this unit” and “in this unit people treat each other with respect.” A neutral response (n = 283; 56%) was received from the participants concerning the expectations and actions of supervisor regarding patient safety, with an aggregated mean score of 3.17+0.50. However, positive response for both “My supervisor/manager says a good word when he/she sees a job was done that render the establishment of patient safety procedures” and “my supervisor/manager seriously considers staff suggestions for improving patient safety” was obtained (69% and 67%, respectively) (Table 3). Continuous improvement in organizational learning was rated positive by 81% of the nurses, with an average mean score of 3.93+0.61. Whereas highest average positive rating (89%) was observed for “we are actively doing things to improve patient safety.” Aggregate rating of 3.33+0.68 was obtained as a neutral response for overall management support for patient safety. Moreover, the highest positive average rating (66%) was obtained for “The actions of hospital management show that patient safety is a top priority.”

|

Table 3 Results of Overall Patient Safety Culture (N-503) |

|

Table 4 Summary of the 12 Dimensions and Overall Patient Safety Culture (N-503) |

The nurses (57%) reported a neutral response concerning the overall perceptions of the patient (3.32+0.56). Highest positive rating (77%) among the items in the dimension was observed for “Our procedures and systems are good at preventing errors from happening.” Positive response was received for feedback and communication by 66% of the nurses (3.71±0.80). Moreover, the highest positive rating (72%) was also observed for “In this unit, we discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again.” For communication openness, 45% of the nurses reported a neutral response (3.38±0.78). The highest positive rating (63%) was received for “Staff will freely speak up if they see something that may negatively affect patient care.” Almost 51% of the nurses rated teamwork as positive across the unit (3.39±0.61). Majority of the participants (73%) responded in agreement for “It is often unpleasant to work with staff from other hospital units.“

There was disagreement among the nurses to obtain a negative rating (56%). However, the negative wording of the item resulted in positive rating. Moreover, the highest negative rating (75%) was received for “We work in ‘crisis mode,’ trying to do too much, too quickly” suggesting opposite meaning of the item holds true. The nurses (40%) reported positivity for handoffs and transitions with a rating and aggregated (3.09±0.75). Moreover, a positive rating (48%) was received for “Important patient care information is often lost during shift changes.“

The negative rating of 57% was provided by the nurses for the non-punitive response (2.48±0.72). The highest negative rating (66%) was observed for “Staff worry that mistakes they make are kept in their personnel file.” This resulted in negative wording of the items indicating positive response from the nurses. Neutral response was obtained for patient safety culture among the nurses (3.29±0.32). Moreover, there was disagreement in the level of patient safety culture in their hospital of employment or assigned unit (Table 4).

Table 5 shows the Pearson correlation results, which depict that nurses’ overall perception of patient safety culture and patient safety culture dimensions were significantly associated (p-value < 0.001). This caused a significant effect (i.e. r >5). The association of nurse’s overall perception with teamwork within units was found significant (r = 0.613), along with feedback and communication about error (r = 0.715), Management Support for Patient Safety (r = 0.549), Continuous improvement (r = 0.512), and Teamwork Across Units (r = 0.613).

|

Table 5 Association Between Nurses' Overall Perception of Patient Safety Culture and Patient Safety Culture Dimensions |

The results of the regression analysis have been presented in Table 6. The findings show that as the frequency rating of an event increase by one unit, the overall patient safety culture increases by 083. Similar is the case for teamwork within the hospital units, supervision and safety-promoting actions, organizational learning hospital management support for patient safety, perceptions of safety, feedback and communication about the error, communication openness, and teamwork across hospital units (a value ranging from 0.084 to 0.083). The significance value (p-value < 0.001) was achieved for patient contact or interaction (p-value 0.022), patient safety grade (p-value 0.017), number of events reported in past 12 months (0.019), frequency of event reporting (p-value < 0.001), Teamwork Within Hospital Units, Supervisor/manager expectations and actions promoting safety, organizational learning–continuous improvement, hospital management support for patient safety, perceptions of safety, feedback and communication about error, communication openness, teamwork across hospital units, staffing, overall hospital handoffs and transitions, and overall non-punitive response to error (p-value < 0.001).

|

Table 6 Regression Analysis |

Discussion

Patient safety culture plays an important role in developing healthcare safety culture; therefore, it imposes a negative impact on the patient’s safety culture. The present study has identified staffing, non-punitive response to errors, organizational learning improvement, feedback about the error, and teamwork as the areas of strength. It is believed that people support each other and provide easy comment in a hospital setting. On the contrary, lack of mutual trust among healthcare workers, conflicts, and lack of evidence of teamwork and collaboration raised dissatisfaction and feelings of being overstressed among the nurses.21 These results were consistent with a few of the previous studies.22–25

The present study has also shown that individuals actively participate in certain activities that improve patient safety because the majority of them do not feel like their mistakes are held against them and discuss ways to prevent errors from happening again in the hospital. Facilitation of trusting culture in quality of care contributes towards improvement in organizational learning and patient safety. Based on the previous studies, facilitating the trusting culture results in the creation of a balance between the highly punitive culture and culture free of guilt.26,27 It has been shown that managing improvement to the organization and leadership support in the hospital is possible by reducing punitive response to error and encouraging supportive coworker, supervisor, and institutional interactions.13 A study conducted by Hessels and Larson24 emphasized on common attributes to a positive patient safety culture that included staffing and workload, teamwork, resources, leadership support, work design, perception of organizational commitment, and non- punitive response to errors. Vifladt et al23 mainly focused on the staffing component and stated that positive safety culture results due to the absence of burnout and increased ability to cope with stressful situations.

The present study showed that appropriate nurse staffing and working hours in a hospital setting result in enhanced quality and safety of care. These results are in agreement with previous studies conducted by Coetzee et al28 Cho et al29 and Old et al.30 It can be stated that cultural variances between the nurses and their managers have a significant impact on organizational support as the nurses may belong to different cultures. For instance, in the nursing unit, the nurses may feel that they are being supported in a situation where they commit mistakes; however, they are not worried that the mistakes they make are recorded in their personnel file. Setting up this kind of safety culture for the nurses prioritizes the improvement and maintenance of patient safety culture concerning the management and nurses within the hospital setting.

The areas of improvement specified in the present study include management support for patient safety, teamwork across units, actions promoting patient safety, communication openness, supervisor/manager expectations, and overall perceptions of patient safety. The overall ratings were neutral, suggesting the need for improvement to be positively rated, although some items describing these components were positively rated, when taken as a whole in every component of patient safety culture. However, previous studies conducted by Hessels and Larson,24 Hamaideh,31 and Gunes and Zaybak32 stated that open communication among nurses resulted in a positive patient safety culture. However, the reporting system of adverse events was reported for manager support and actions and shared perception/expectation of safety importance. Aboshaiqah and Baker26 were successful in identifying communication, actions promoting safety, hospital handoffs and transitions, and manager/supervisor expectations as areas for improvement to have a positive patient safety culture in the hospital.

The managers need to consider the safety culture as their attitudes and values because they are the ones who connect and relate to the perception of risk and safety in the hospital to enhance positive patient safety culture perceptions among staff nurses. There is also a need for practice workshop with discussion and negotiation of shared goals for improving the patient safety culture. A similar study conducted by Webair et al33 showed that team meetings and day-to-day interaction play a significant role in enhancing the further liaison and sharing, which is likely to make patient safety a common and conscious goal. This highlights the need for studying handoffs and transition practices for formulating strategies that will improve the procedure and thereby improve patient safety. Positive overall patient safety culture in an organization prevails as a result of cost-effective enhancement of work environment, focus on management support, leadership, and teamwork. This approach in the present study explains the fact that in Arar hospitals, nurses belonging to different cultures are exposed to high risk of missed information and data related to patient’s situations during handoffs.

The study recommends that for improving patient safety and mitigating its detrimental effect, it is important that organizations learn from the previous adverse events. It suggests that safety culture in the organization can be improved through benchmarking, which helps in improving the knowledge of the nurses and delivering the best services. Since neutral results are found concerning the prevalence of the safety culture, therefore, to promote it further, different strategies can be introduced that comprise different components. These strategies should be related to the effective flow of work processes concerning the changes in the shift and handovers to ensure that no information is loss for the patients and their treatment. Similarly, cooperation, coordination, and integration of the hospital staff should be promoted to connect the fragmented care units. Likewise, the prospects for blaming culture should be resolved and eliminated for improved accountability, prioritize, detection of the system failures, and devising effective methods for reducing them.

The findings of the present study are limited because the value of the comments provided by the nurses was underestimated on the state of patient safety in their respective organizations. Moreover, the study lacked sample randomization, and it increased the period of data collection. The perception of the organization’s patient safety culture was not compared between the staff nurses and their managers. Another study limitation is the unbalanced distribution of participants in the six-hospital settings.

Conclusion

The present study has focused on the perceptions of nurse staff regarding safety culture and knowledge of safety measures in Saudi Arabia. It used a cross-sectional study design and analyzed the perception of nurses at six different hospitals. The survey findings revealed that teamwork, staffing, organizational learning improvement, non-punitive response to errors, and feedback about the error were practiced among the nurses. These, along with organizational learning and continuous improvement, were identified as the building blocks of patient safety culture that facilitates delivering safe patient care. It concluded that organizational learning and improvement in patient safety helps in creating a trust culture in hospitals. Overall, a neutral level of safety culture was found in all Saudi Hospitals. The present study established that factors such as appropriate nurse staff and working hours are critical for enhancing patients’ care quality and safety. The study recommends that reporting and communicating errors should be prioritized among the staff, and the management must devise appropriate policies for reducing the errors. Moreover, management support for patient safety is instrumental in improving the patient safety culture in Arar Hospitals. The future studies need to conduct in-depth studies and consider the maintenance of patient safety culture. Moreover, the same study could be replicated by involving care providers as study participants.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgment

The authors are very thankful to all the associated personnel in any reference that contributed in/for the purpose of this research.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Alahmadi HA. Assessment of patient safety culture in Saudi Arabian hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5):e17. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.033258

2. Iriviranty A, Ayuningtyas D, Misnaniarti M. Evaluation of patient safety culture and organizational culture as a step-in patient safety improvement in a hospital in Jakarta, Indonesia. J Patient Safety Qual Improv. 2016;4(3):394–399.

3. Ulrich B, Kear T. Patient safety and patient safety culture: foundations of excellent health care delivery. Nephrol Nurs J. 2014;41:5.

4. Morello RT, Lowthian JA, Barker AL, McGinnes R, Dunt D, Brand C. Strategies for improving patient safety culture in hospitals: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(1):11–18. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000582

5. World Health Organization. Consultative meeting planning for the global patient safety challenge: medication safety, 19–20 April 2016, WHO Headquarters Geneva, Switzerland: meeting report (No. WHO/HIS/SDS/2016.20). World Health Organization; 2016.

6. Hickner J, Smith SA, Yount N, Sorra J. Differing perceptions of safety culture across job roles in the ambulatory setting: analysis of the AHRQ medical office survey on patient safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(8):588–594. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003914

7. Campione JR, Yount ND, Sorra J. Questions regarding the authors’ conclusions about the lack of change in Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPS) scores related to reduction of hospital-acquired infections. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):e3. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007360

8. Aboneh EA, Look KA, Stone JA, Lester CA, Chui MA. Psychometric properties of the AHRQ community pharmacy survey on patient safety culture: a factor analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(5):355–363. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004001

9. Weaver SJ, Marsteller JA, Wu AW, Ismail MN, Pronovost PJ. Patient safety culture and medical liability—recommendations for measurement, analysis, and interpretation: a commentary. Adv Patient Safety Med Liability. 2017;57.

10. Ali H, Ibrahem SZ, Al Mudaf B, Al Fadalah T, Jamal D, El-Jardali F. Baseline assessment of patient safety culture in public hospitals in Kuwait. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):158. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2960-x

11. Thomas-Hawkins C, Flynn L. Patient Safety Culture and Nurse-Reported Adverse Events in Outpatient Hemodialysis Units. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 2015;29(1):1–14.

12. Lee SH, Phan PH, Dorman T, Weaver SJ, Pronovost PJ. Handoffs, safety culture, and practices: evidence from the hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):254. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1502-7

13. Quillivan RR, Burlison JD, Browne EK, Scott SD, Hoffman JM. Patient safety culture and the second victim phenomenon: connecting culture to staff distress in nurses. Joint Commission J Quality Patient Safety. 2016;42(8):377–AP2. doi:10.1016/S1553-7250(16)42053-2

14. Hessels AJ, Agarwal M, Saiman L, Larson EL. Measuring patient safety culture in pediatric long-term care. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2017;10(2):81–87. doi:10.3233/prm-170432

15. Gambashidze N, Hammer A, Brösterhaus M, Manser T. Evaluation of psychometric properties of the German hospital survey on patient safety culture and its potential for cross-cultural comparisons: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018366. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018366

16. Aljadhey H, Al-Babtain B, Mahmoud MA, Alaqeel S, Ahmed Y. Culture of safety among nurses in a tertiary teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Trop J Pharm Res. 2016;15(3):639–644. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v15i3.28

17. Al-Awa B, Jacquery A, Almazrooa A, et al. Comparison of patient safety and quality of care indicators between pre and post accreditation periods in King Abdulaziz University Hospital. Res J Med Sci. 2011;5(1):61–66. doi:10.3923/rjmsci.2011.61.66

18. Stavrianopoulos T. The development of patient safety culture; 2014. Available from: http://www.hsj.gr/medicine/the-development-of-patient-safety-culture.php?aid=3262.

19. Elmontsri M, Almashrafi A, Banarsee R, Majeed A. Status of patient safety culture in Arab countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e013487. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013487

20. Sorra JS, Nieva VF, Famolaro T, Dyer N. Hospital survey on patient safety culture agency for healthcare research and quality. AHRQ Publ. 2007;04-0041.

21. Fujita S, Ito S, Seto K, Kitazawa T, Matsumoto K, Hasegawa T. Risk factors of workplace violence at hospitals in Japan. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(2):79–84. doi:10.1002/jhm.976

22. Onge JL, Parnell RB. Patient-centered care and patient safety: a model for nurse educators. Teach Learn Nurs. 2015;10(1):39–43. doi:10.1016/j.teln.2014.08.002

23. Vifladt A, Simonsen BO, Lydersen S, Farup PG. The association between patient safety culture and burnout and sense of coherence: a cross-sectional study in restructured and not restructured intensive care units. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2016;36:26–34. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2016.03.004

24. Hessels AJ, Larson EL. Relationship between patient safety climate and standard precaution adherence: a systematic review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92(4):349–362. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.08.023

25. Salmela S, Koskinen C, Eriksson K. Nurse leaders as managers of ethically sustainable caring cultures. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(4):871–882. doi:10.1111/jan.13184

26. Aboshaiqah AE, Baker OG. Assessment of nurses’ perceptions of patient safety culture in a Saudi Arabia hospital. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(3):272–280. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182855cde

27. Kirwan M, Matthews A, Scott PA. The impact of the work environment of nurses on patient safety outcomes: a multi-level modelling approach. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(2):253–263. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.020

28. Coetzee SK, Klopper HC, Ellis SM, Aiken LH. A tale of two systems—nurses practice environment, wellbeing, perceived quality of care and patient safety in private and public hospitals in South Africa: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(2):162–173. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.002

29. Cho SH, Lee JY, June KJ, Hong KJ, Kim Y. Nurse staffing levels and proportion of hospitals and clinics meeting the legal standard for nurse staffing for 1996~ 2013. J Korean Acad Nurs Administration. 2016;22(3):209–219. doi:10.11111/jkana.2016.22.3.209

30. Olds DM, Aiken LH, Cimiotti JP, Lake ET. Association of nurse work environment and safety climate on patient mortality: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;74:155–161. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.004

31. Hamaideh SH, Al-Omari H, Al-Modallal H. Nursing students’ perceived stress and coping behaviors in clinical training in Saudi Arabia. J Mental Health. 2017;26(3):197–203. doi:10.3109/09638237.2016.1139067

32. Güneş ÜY, Zaybak A. A study of Turkish critical care nurses’ perspectives regarding family‐witnessed resuscitation. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(20):2907–2915. doi:10.1111/jcn.2009.18.issue-20

33. Webair HH, Al-Assani SS, Al-Haddad RH, Al-Shaeeb WH, Selm MA, Alyamani AS. Assessment of patient safety culture in primary care setting, Al-Mukala, Yemen. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):136. doi:10.1186/s12875-015-0355-1

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.