Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Adaptation and Validation of Indonesian Version of the Commitment to Change Scale

Authors Faisaluddin F , Fitriana E, Nugraha Y, Hinduan ZR

Received 29 September 2022

Accepted for publication 15 January 2023

Published 26 January 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 251—259

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S391379

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Faisaluddin Faisaluddin,1,2 Efi Fitriana,1 Yus Nugraha,1 Zahrotur Rusyda Hinduan1

1Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, West Java, Indonesia; 2Faculty of Health, Universitas Bhamada Slawi, Tegal, Central Java, Indonesia

Correspondence: Faisaluddin Faisaluddin, Email [email protected]

Purpose: The study aims to adapt and validate the Indonesian version of the commitment to change scale that was initially developed by Herscovitch and Meyer.

Methods: Data were collected using an online application among faculty members of several universities who have experienced policy changes from the Indonesian government regarding research-related issues. A total of 204 responses were obtained. The data was validated using the Content Validity Index (CVI), the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), the Convergent and Discriminant correlations as well as the Cronbach’s alpha.

Results: The results demonstrated that commitment to change could be represented by three dimensions of affective, continuance and normative commitment to change, although there is one item that must be adjusted. The results of the Scale-Content Validity Index (S-CVI) show that the commitment to change scale has excellent content validity (S-CVI/Ave = 0.97). CFA results show a good fit, Cronbach’s alpha obtains good results with ACTC (α = 0.71); CCTC (α = 0.83); NCTC (α = 0.77) and Construct Reliability (CR) values obtained are also quite good with ACTC = 0.85; CCTC = 0.86; NCTC = 0.86. From the results of the convergent and discriminant validity tests, it was found that the affective commitment to change positively correlates with job satisfaction and negatively correlates with job stress. However, both continuance and normative commitment to change scale does not correlate with the two variables.

Conclusion: The Indonesian version of the commitment to change scale shows good psychometric properties and has proven valid to provide the measurement of commitment to change, especially for the faculty members in Indonesia.

Keywords: test validation, test adaptation, commitment to change, faculty members

Introduction

An organization is always changing. These changes are often partly unplanned and gradual.1 Therefore, organizations must find solutions to these challenges and problems if they want to survive, prosper, and perform effectively.2 Organizations that are able to adapt to these changes will be able to develop over a long period of time and overcome threats caused by the internal and external environment.3 With no exception for higher educational institutions.

Organizational change in a higher educational institution is affected mostly by external pressures, such as government rules and regulations that occur continuously. This is done to continue to adapt to the times and increase competitiveness with other countries. For this reason, higher educational institutions in Indonesia are required to always be ready to face and anticipate changes, so that they can continue to compete and contribute to improving the quality of human resources. Mangundjaya explains that in order to survive and compete, every organization must change, and this requires commitment from its employees to change.4

Herscovitch & Meyer5 stated that commitment to change was the key point to implementing transformation. If each member of the organization has a commitment to change, the transformation will be successfully applied.6 Previous studies have indicated that positive employee attitudes such as commitment to change play a vital role in employee acceptance of organizational change and its long-term success.6–8 Employee commitment to change is also one of the most important antecedents to avoid failure in change implementation.5,9

The word commitment can be defined as an employee’s attachment to various foci such as the organization as a whole, units within the organization, supervisor or even a change.5,10 In 1991, Meyer & Allen11 proposed a model of organizational commitment. Organizational commitment is defined as a psychological state that leads an employee to maintain his or her organizational membership.11,12 Furthermore, Meyer and Herscovitch13 made some adjustments from the original model and proposed a general model of workplace commitment so that it could be applied to other workplace commitments. With this change, commitment has changed its definition as “a force (mindset) that binds an individual to a course of action of relevance to one or more targets”.5

In contrast to previous research which typically defined commitment to change as a uni-dimensional construct,14,15 Armenakis, Harris and Field16 and Herscovitch and Meyer5 were the first researchers to describe commitment to change as a multi-dimensional construct. Based on the general model of workplace commitment they had presented previously,13 Herscovitch and Meyer5 further introduced a three-component model of commitment to change. They defines a commitment to change as a force (mind-set) that binds an individual to a course of action deemed necessary for the successful implementation of a change initiative.5 This mindset can take different forms: (a) a desire to provide support for change based on a belief in its inherent benefits (affective commitment to change), (b) a recognition that there are costs associated with failing to provide support for change (continuous commitment to change), and (c) a sense of obligation to provide support for change (normative commitment to change). Herscovitch and Meyer5 proved using the EFA test that commitment to change consisted of three factors where the correlation test between factors showed different magnitudes and directions, this indicates that commitment to change is a multidimensional variable.

Until now, there are not many studies that focus on adaptation and validation commitment to change scale. However, this scale becomes very important because change occurs continuously, and employee commitment to change has a very important role in providing success for these changes. Some studies on adaptation and validation of commitment to change were carried out in Canada,17 Pakistan,3,17 India,18 and Turkey.19 In Indonesia itself, although there have been many studies discussing commitment to change,20–22 no studies have been found on the adaptation and validation of commitment to change scale.

Based on previous studies regarding the validation of commitment to change, several differences were found in the results of their studies. For example, the results of a study by Meyer et al17 on an Indian sample showed that the correlation between affective and normative commitment to change was greater than continuance and normative commitment to change. This is different from the two subsequent studies where kalyal et al3 who used Pakistani samples found that the relationship between continuance and normative commitment to change was more significant than affective and normative commitment to change, as well as the study conducted by Soumdjaya et al,18 although both used samples of Indian society, the results obtained were closer study conducted by Kalyal et al compared to Meyer et al. This suggests that even within the same culture, the relationship of normative commitment to change to the other two components of commitment to change varies and more similar studies are needed to gain further insight into them.18

Providing an original scale to people with different languages and cultures certainly has its own obstacles. Some items may not be appropriate due to cultural differences. Thus, careful and in-depth translation and development of culturally appropriate items may be required to address comprehension issues.3 This cultural incompatibility sometimes requires researchers to adjust or eliminate the items to be used as happened in the previous studies.3,18 Beaton23 said that in conducting research on subjects that have different languages and cultures, a poor translation process can lead to instruments that are not equivalent to the original questionnaire. Generic scales are not always culturally sensitive, and thus may need to be adapted for certain contexts. For this reason, it is not permissible to directly use existing or validated scales in other countries that have different languages and cultures. This raises concerns about the misinterpretation of the question.

On the other hand, changes in various organizations that take place continuously make the commitment to change scale a tool that will be needed by many authors and practitioners to determine employee commitment to the changes that occur. Thus, the authors sees that a valid and reliable commitment to change scale will be very important to be used in Indonesia, especially to obtain data and evidence more objectively and scientifically.

Based on these, this study aims to adapt and validate the commitment to change scale (affective, continuance, and normative commitment to change) in the Indonesian Version. The final Indonesian version of the Commitment to Change Scale was tested using the following: (1) to examine its content validity by using Content Validity Index (CVI), (2) to examine its construct validity by using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), (3) to examine its Convergent and Discriminant validity by investigating the relationship between commitment to change with job satisfaction and perceived Stress. Authors correlated commitment to change with job satisfaction and job stress because in previous studies, job stress24,25 and job satisfaction20–22,26 were shown to have a significant relationship with commitment to change, (4) reliability was verified using Cronbach’s alpha.

Methods

Procedure

This research was conducted through several stages in accordance recommended by Beaton et al.23 The first step was to ask permission from the people who developed the Commitment to Change Scale measuring instrument.5 The next stage is to carry out a cross-cultural adaptation, starting from (1) forward translation by two people, who had English education and translation study backgrounds, (2) translation synthesis, which is discussing the results of the translation among the authors, translator 1 and translator 2, (3) backward translation by natives with applied linguistic backgrounds and another person with English education backgrounds, (4) expert committee review, where the minimum composition consists of methodologist, professional in the research field, language professionals, and translators (forward and backward translators) involved in the process to date.23 In this study, the expert committee was reviewed by 2 translators, 3 people who mastered psychological concepts, 1 methodologist, and 1 linguist. (5) pre-testing with 30 subjects. Furthermore, the authors carried out the validity testing phase by testing content validity, construct validity, and reliability.

In the process of collecting data, authors go to several higher educational institution to ask for permission to conduct research in their place. Higher educational institution that provide support will provide access to be able to distribute online questionnaires to faculty members. Before filling out the scale they were asked to read and fill out a consent form regarding their willingness to fill out the scale.

Participants

The participants of this study were purposively sampled based on a study conducted by Beaton et al23 regarding the process of cross-cultural adaptation with self-reported measures. Participants in this study were 204 faculty members from six universities in Indonesia who had worked for more than 6 years, this was done to ensure they had known and experienced two work situations, before and after the change. Researchers have suggested that the sample used should be no less than 200, whereas in terms of the ratio of observations to variables, the general rule is to have a minimum value from five times as many observations as the number of variables to be analyzed, and a more acceptable sample size has a ratio of 10:1.27 In this study there are 18 variables to be analyzed so that it meets the recommended minimum number.

Based on the demographic data obtained in this study, it can be described that most of the participants were female 57.4% (N = 117). Participants were aged 25 years and over with the majority being in the age range of 25–34 years, 46.1% (N = 94) and the others are 35–44 years, 41.7% (N = 85); 45–54 years, 10.8% (22); and over than 55 1.4% (3). Based on work tenure, most have worked for 7–12 years 77.4% (N=158), the others is 13–18 years 10.3% (N=21) and more than 18 years 12.3% (N = 25). Based on academic rank there were 93.1% (N=190) assistant professors and 6.9% (N=14) were associate professors. Based on the educational level there were 89.7% (N=183) participants with master’s degree and 10.3% (N=21) were doctoral degree.

Study Measures

To measure commitment to change we used a measuring tool developed by Herscovitch & Meyer.5 This tool consists of 3 components; Affective Commitment to Scale (ACTC), Continuance Commitment to Scale (CCTC), and Normative Commitment to Scale (NCTC). Examples of items that have been converted into Indonesian are: ACTC, eg item 1, “Saya percaya adanya manfaat pada perubahan ini” (I believe there is a benefit in this change). CCTC, eg item 7, “Saya tidak memiliki pilihan lain selain mengikuti perubahan ini” (I have no other choice but to follow this change). NCTC, eg item 13, “Saya merasa bertanggung jawab untuk mewujudkan perubahan ini” (I feel responsible for making this change happen). Each component consists of 6 questions with a total of 18 items on a scale of 1–7 (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The use of this scale refers to the scale developed by Herscovitch & Meyer.5

Job Satisfaction Survey (JSS) developed by Spector24 was used to measure job satisfaction. JSS has 36 items to measure employee perceptions and attitudes including; salary, promotions, supervision, additional benefits, contingent rewards, operating conditions, co-workers, nature of work, and communication. Respondents were asked to indicate their views by filling in one of the six-point Likert-type scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The research used JSS which was translated and adapted by Azra et al25 with a reliability coefficient of 0.93. The Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.92.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) by Cohen & Janicki-Deverts,26 was used to measure job stress. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency by filling in one of the 5-point Likert-type scales starting from never to very often. This study uses PSS which has been translated by Saraswati,28 with a reliability coefficient of 0.90, by eliminating 5 items. The reliability coefficient in this study was 0.88, but none of the items were omitted.

Data Analyses

To see the socio-demographic picture such as gender, age, marital status, grade, education, and length of work in this study, descriptive statistics were used. Standard deviation and Mean were used to describe the variable. Data analysis used Content Validity Index (CVI) consisting of Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and Scale Content Validity Index (S-CVI). Then the authors also used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), convergent and discriminant correlation analysis, and reliability analysis.

In conducting content validity using CVI, Lynn29 recommends a minimum of three experts, but preferably no more than 10. In this study, there were seven experts. A four-point ordinal scale was used to be rated by experts on each item according to relevance, clarity, simplicity and ambiguity,30 which included the following: (1) not relevant; (2) somewhat relevant; (3) quite relevant; and (4) highly relevant. The I-CVI was calculated as the number of experts giving a rating of 3 or 4 divided by the total number of experts for each item. The I-CVI should be 1.00 when there are five or fewer experts. Meanwhile, if there are 6 or more experts, the standard can still be lowered, but not less than 0.78.31

CFA was tested using Lisrel 8.80. Convergent and discriminant correlations were tested using the Pearson correlation coefficient by correlating ACTC, CCTC, NCTC with JSS and PSS. Reliability was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha and Construct Reliability (CR).

Ethical Consideration

The ethics enforcement of this research is supplemented by Universitas Padjadjaran Research Ethics Committee License no. 824/UN6.KEP/ EC/2020 and informed consents.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

Based on data analysis using t-test and ANOVA, demographic variables do not have implications for CCTC. The difference was found that age, tenure, academic rank, and education affect ACTC. Age and tenure also affect CCTC. Thus, it can be said that faculty members with an age range of 45-54 years have the highest affective commitment to change than any other age ranges. The higher their tenure, academic rank, and education, the higher their affective commitment to change. On the other side, the higher their age and working period will increase their normative commitment to change, but this will decrease when they reach the age of 55 and over. The results of the t-test and ANOVA are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants |

Content Validity

In this study, authors used CVI to measure content validity. As noted by Lynn,29 authors compute two types of CVIs. The first type involves the content validity of individual items and the second involves the content validity of the overall scale. Based on the results of the I-CVI measurement, it is known that there is one item less than 0.78 (I-CVI = 0.71). The authors revised this item before the CFA. At first the item reads “It would be too costly for me to resist this change”, and after the authors revised it to “I risked a lot of things if I resisted this change”. This is in accordance with Polit & Beck31 stating that information from the I-CVI is used by authors as a basis for revising, removing, or replacing items that are below the standard. S-CVI/Ave = 0.97 indicates that this scale has excellent content validity because of higher than 0.90.31

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The results of the model fit test showed good fit results. This is because the results of the 6 indicators that there are 7 of them have met. To get good fit results, P value must be > 0.05, RMSEA Should be less than 0.80,32 while GFI, AGFI should be above or equal to 0.90,33 so do NFI, NNFI and CFI.34 The data in this study shows that χ2 = 240.73 (P = 0.000), RMSEA = 0.07, GFI = 0.90, AGFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.90, NNFI = 0.90, and CFI = 0.92.

Cronbach’s alpha obtained good results, with ACTC (α = 0.71); CCTC (α = 0.83); and NCTC (α = 0.77). Whereas in testing the Construct Reliability (CR) values obtained are also quite good with ACTC = 0.85; CCTC = 0.86; NCTC = 0.86.

Based on the CFA for the model, each item has a t value greater than 1.96 and a loading factor in the range of 0.50 to 0.86. If we break it down into each dimension, then the ACTC loading factor ranges from 0.50–0.74; CCTC = 0.51–0.83; and NCTC 0.50–0.86, we can see this in more detail in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Loading in Particular Items in ACTC, CCTC, and NCTC |

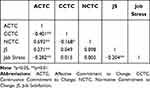

Convergent and Discriminant Correlation

The convergent and discriminant validity of the Indonesian version of Commitment to Change was examined by using Pearson’s correlation to correlate commitment to change with job satisfaction and job stress, each component of commitment to change was correlated with job satisfaction and job stress to obtain a more specific picture. The correlation coefficient of each variable can be seen in Table 3.

|

Table 3 Inter Correlation Between ACTC, CCTC, NCTC, Job Satisfaction, and Job Stress |

The table above shows that ACTC was positive and significantly related to Job Satisfaction with coefficient correlation of 0.271 and negative and significantly related to Job Stress with coefficient correlation of −0.282. CCTC and NCTC were not related both to Job Satisfaction and Job Stress. The highest correlation is ACTC with Job Stress, and the lowest is NCTC with Job Stress.

Discussion

The main aim of this research is to adapt and validate the commitment to change scale (affective, continuance, and normative commitment to change) in the Indonesian Version. This instrument has been tested using CVI, and CFA, as well as convergent and discriminant validation. All three components of the commitment to change scale were also found to have acceptable levels of reliability.

Based on the content validity test, it was found that the S-CVI was acceptable As for the I-CVI measurement, there is one item that is below the set standard. This happens because the word “mahal” which is a translation of the word “costly” is deemed inappropriate by some experts on the existing sentence For that reason, the authors revised it with more appropriate words, before being tested using CFA.

CFA test results showed that all items have a factor loading that exceeds the minimum requirement. This shows that the Commitment to Changing Scale is a measurable construct that can be distinguished from the others. Furthermore, in this study it was found that the highest loading factor was found in items that are part of the NCTC (0.86). This is not surprising considering that Indonesia is one of the countries that tend to have a collective culture compared to individual ones.35

Another finding of this study is the higher correlation between ACTC and NCTC compared to others. This is in line with expectations from collective culture and reinforces other studies using Indian samples,17 although other studies have also found a greater correlation between ACTC and CCTC in Pakistan and Indian samples.3,18 In this study, this may occur because Indonesian people like to socialize, love to return favors, want to be accepted by groups, and take benefit from their involvement in the group.

The results of the convergent and discriminant correlation tests show similarities with previous studies, where commitment to change is positively correlated with job satisfaction20–22,36 and negatively with job stress.3,37 Although in this study only ACTC has a relationship with these two variables, this is sufficient to indicate a commitment to change behavior. This is in line with Herscovitch & Meyer5 saying that the emergence of one form of commitment is enough to achieve a focal behavior.

This explains that when people are satisfied with their jobs they will be committed to the change because they perceive that change is important for the organization and believe in the inherent benefits. On the other hand, the more a person feels stressed, the lower the level of ACTC. This finding is in line with Kalyal et al3 who said that since ACTC has shown a willingness to support change initiatives, variables such as ambiguity or work-related stress would be negatively correlated with this particular type of commitment.

Another interesting finding from this study is that there is no correlation between CCTC and NCTC on both job satisfaction and job stress. There is no correlation between CCTC and Job Satisfaction. This study supports the study from Hinduan et al,36 but is different from other studies which say that CCTC has a negative correlation to job satisfaction22 and positive to stressors.3 However, NCTC is still in line with two previous studies saying that NCTC correlates with neither Job Satisfaction22 nor Stressors,3 although there are differences in other studies saying that NCTC has a positive correlation with job satisfaction.36 With these findings it can be said that if people are satisfied with their work, they will prefer to develop an attitude of commitment to change because it is based on a belief in its inherent benefits rather than because of fear of costs or just a sense of obligation in providing support for change. On the other hand, the authors also argue that no correlation occurs because the stressor is a stimulus that creates ambiguity and uncertainty for those affected so it will be difficult to decide whether they will develop CCTC, NCTC, or choose not to commit.

Thus, research conducted using Indonesian samples can add broader insights and further complement previous studies that have been conducted in several countries with eastern cultures such as Pakistan and India, and provide some evidence that commitment to change scale from Herscovitch and Meyer’s (2002) can be generalized to eastern world countries. Besides this, the findings in this study can also help management to be able to increase employee commitment in dealing with change. This study provides more insight that by providing satisfaction to employees and minimizing employee stress levels can increase employee commitment to change, especially from an affective perspective.

Study Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the limited respondent. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the authors were unable to collect data directly and the potential respondents were not comfortable in filling out the electronic questionnaire. The limitation of online survey might also affected the quality of the data although the authors had already taken several steps to anticipate the effects.

Conclusions

The process of adapting Commitment to change scale to the Indonesian version has been carried out in accordance with the existing steps and procedures. Based on the empirical test of the validity and reliability of the Indonesian version of commitment to change scale, the results meet the criteria. Thus commitment to change scale has satisfactory psychometric properties and can be used in Indonesian population. This scale can be compared with other international research and can be used for other studies in organizational settings.

Data collection in this study was carried out during the Covid 19 pandemic and it was not possible to collect data directly, so it was difficult to ascertain the condition of the participants in filling out the questionnaire. It is hoped that with the decline in the Covid-19 pandemic, further research can collect data directly to further ascertain the condition of the participants in filling out the questionnaire provided.

Ethical Approval

All participants gave their informed consent to be involved before they participated in this study. Informed consent included the publication of anonymized responses. All procedures performed were by the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standard. All procedures performed in this study were by ethical standards and the procedures were approved by the ethics committee of Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Burke WW. Organization Change: Theory & Practice.

2. Jones GR. Organizational Theory, Design, and Change.

3. Kalyal HJ, Sverke M, Saha SK. Validation of the herscovitch-Meyer three-component model of commitment to change in Pakistan. In:

4. Mangundjaya, W. Organizational commitment’s profile during the transformation and its relation to employee commitment to change (A study at oil company in Indonesia during large-scale organizational change) 2013. In:

5. Herscovitch L, Meyer JP. Commitment to organizational change: extension of a three-component model. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(3):474–487. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.474

6. Shum P, Bove L, Auh S. Employees’ affective commitment to change: the key to successful CRM implementation. Eur J Mark. 2008;42(11–12):1346–1371. doi:10.1108/03090560810903709

7. Van Dierendonck D, Jacobs G. Survivors and victims, a meta-analytical review of fairness and organizational commitment after downsizing. Br J Manage. 2012;23(1):96–109. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00724.x

8. Parish JT, Cadwallader S, Busch P. Want to, need to, ought to: employee commitment to organizational change. J Organ Chang Manage. 2008;21(1):32–52. doi:10.1108/09534810810847020

9. Oreg S. Resistance to change: developing an individual differences measure. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(4):680–693. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.680

10. Ford JK, Weissbein DA, Plamondon KE. Distinguishing organizational from strategy commitment: linking officers’ commitment to community policing to job behaviors and satisfaction. Justice Q. 2003;20(1):159–185. doi:10.1080/07418820300095491

11. Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 1991;1(1):61–89.

12. Allen NJ, Meyer JP. Organizational socialization tactics: a longitudinal analysis of links to newcomers’ commitment and role orientation. Acad Manage J. 1990;33(4):847–858. doi:10.5465/256294

13. Meyer JP, Herscovitch L. Commitment in the workplace Toward a general model. Hum Resour Manag Rev. 2001;11:299–326. doi:10.1016/S1053-4822(00)00053-X

14. Lau C-M, Woodman RW. Understanding organizational change: a schematic perspective. Acad Manage J. 1995;38(2):537–554. doi:10.5465/256692

15. Coetsee L. From resistance to commitment. Public Adm Q. 1999;23(2):204–222.

16. Armenakis AA, Harris SG, Feild HS. Paradigms in Organizational Change: change Agent and Change Target Perspectives. In: Golembiewski RT, editor. Handbook of Organizational Behavior. CRS Press; 1999:631–658.

17. Meyer JP, Srinivas ES, Lal JB, Topolnytsky L. Employee commitment and support for an organizational change: test of the three-component model in two cultures. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2007;80(2):185–211. doi:10.1348/096317906X118685

18. Soumyaja D, Kamalanabhan TJ, Bhattacharyya S. Employee commitment to organizational change: test of the three-component model in Indian context employee commitment to organizational change: test of the three-component model in Indian context. J Transnatl Manage. 2011;16:239–251. doi:10.1080/15475778.2011.623654

19. Toprak M, Aydin T. A study of adaptation of commitment to change scale into Turkish. Electron Int J Educ Arts Sci. 2015;1(2):35–54.

20. Nugraheni UG, Hermawan A, Kuswanto S. Job satisfaction, motivation and commitment to change of stated owned enterprises ministry employee of Indonesia. Asian Soc Sci. 2019;15(4):94. doi:10.5539/ass.v15n4p94

21. Wulandari P, Mangundjaya W, Utoyo DB. Is job satisfaction a moderator or mediator on the relationship between change leadership and commitment to change? Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2015;172:104–111. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.342

22. Mangundjaya WL. Predictors of commitment to change: job satisfaction, organizational trust and psychological empowerment. In:

23. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi:10.1080/000163599428823

24. Spector PE. Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: development of the job satisfaction survey. Am J Community Psychol. 1985;13(6):693–713. doi:10.1007/BF00929796

25. Azra MV, Etikariena A, Haryoko FF. The effect of job satisfaction in employee’s readiness for change. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;503–510. doi:10.1201/9781315225302

26. Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;42(6):1320–1334. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00900.x

27. Hair J, Black W, Babin B, Anderson R. Multivariate Data Analysis. Cengage Learning; 2019; doi:10.1002/9781119409137.ch4

28. Saraswati KDH. Perilaku Kerja, perceived stress, dan social support pada mahasiswa internship. J Muara Ilmu Sos Humaniora. 2017;1(1):216. doi:10.24912/jmishumsen.v1i1.352

29. Lynn MR. Determination and Quantification on content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35:382–386. doi:10.1097/00006199-198611000-00017

30. Yaghmaie F. Content validity and its estimatimation. Spring. 2003;3(1):25–27. doi:10.22037/JME.V311.870

31. Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–497. doi:10.1002/nur.20147

32. MacCallum R, Browne M, Sugawara H. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(2):130–149. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

33. MacCallum RC, Hong S. Power analysis in covariance structure modeling using GFI and AGFI. Multivariate Behav Res. 1997;32(2):193–210. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3202_5

34. Bentler PM. Comparative fit indices in structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

35. Hofstede G Geert Hofstede, culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviours, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publ. Published online 2002:1–621.

36. Hinduan ZR, Wilson-Evered E, Moss SA, Scannell E. Leadership, work outcomes and openness to change following an Indonesian bank merger. Asia Pacific J Hum Resour. 2009;47(1):59–78. doi:10.1177/1038411108099290

37. Rashid H, Zhao L. The Impact of Job Stress and Its Antecedents on Commitment to Change among IT Professionals in Global Organizations Humayun. In:

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.