Back to Journals » International Journal of Women's Health » Volume 6

Acceptability of artificial donor insemination among infertile couples in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria

Authors Ugwu O , Odoh G, Obi S, Ezugwu F

Received 21 October 2013

Accepted for publication 17 December 2013

Published 12 February 2014 Volume 2014:6 Pages 201—205

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S56324

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Emmanuel O Ugwu,1 Godwin U Odoh,1 Samuel N Obi,1 Frank O Ezugwu2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku/Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria; 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Enugu State University Teaching Hospital, Parklane, Enugu, Nigeria

Background: Male factor infertility presents one of the greatest challenges with respect to infertility treatment in Africa. Artificial insemination by donor semen (AID) is a cost-effective option for infertile couples, but its practice may be influenced by sociocultural considerations. The purpose of this study was to determine the awareness and acceptability of AID among infertile couples in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria, and identify the sociocultural factors associated with its practices.

Methods: Questionnaires were administered to a cross-section of 200 consecutive infertile couples accessing care at the infertility clinics of two tertiary health institutions in Enugu, Nigeria, between April 1, 2012 and January 31, 2013.

Results: Among the 384 respondents, the level of awareness and acceptability of AID were 46.6% (179/384) and 43% (77/179), respectively. The acceptability rate was significantly higher among female respondents, women with primary infertility, and those whose infertility had lasted for 5 years and beyond (P<0.05). The major reasons for nonacceptance of AID were religious conviction (34.7%, n=33), cultural concern (17.9%, n=17), fear of contracting an infection (17.9%, n=17), and fear of possibility of failure of the procedure (12.6%, n=12).

Conclusion: Health education and public enlightenment are advocated to increase awareness and dispel the current misconceptions about AID in our environment.

Keywords: acceptability, artificial insemination, donor semen, infertile couples, Nigeria

Introduction

The impact of male infertility and its attendant consequences in the Igbo-speaking areas of Nigeria has been described by previous authors as emotionally and psychologically devastating.1 This is due to the high premium attached to child-bearing in this region of the country and the misconception that the only recognizable sign of manhood is the ability to propagate oneself.2 The male factor contributes up to 55%–93% of the burden of infertility in southeastern Nigeria,3 and this no doubt presents one of the greatest challenges to infertility treatment in the region. The conventional methods of treatment have low effectiveness, so the trend in management has shifted to use of assisted reproductive techniques, including artificial insemination by donor semen (AID).4

Artificial donor insemination involves use of donor semen to achieve pregnancy in a woman whose husband is severely oligospermic or azoospermic. Practice of this procedure in Nigeria and most of sub-Saharan Africa is mostly limited to a few specialist centers, and even in those centers, the level of acceptability varies as a result of various constraints, including sociocultural factors such as cultural taboos, perception of the technique as shameful, and religious bias.4,5

A study done in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria, among medical students in 2008 showed that only 24 of 81 female respondents (29.6%) were willing to accept donor semen should the need arise.4 In a study done in Yaoundé, Cameroon, in 1992, only 35.3% of infertile respondents were aware of the procedure, and despite the high value the respondents placed on child-bearing, only 19.6% of infertile respondents would actually accept the practice of AID if the need arose.5

Further, infertility treatment by in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer is expensive, and the availability of such services is limited in low-resource settings, including Nigeria.5 The cost of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer in Nigeria (based on personal interview of various experts in the field) is 350,000–1,500,000 naira (US$ 2,187.00–9,375.00) depending on the health facility and pretreatment requirements. Public health facilities are much cheaper than private health facilities. The cost of AID is generally about 50,000–150,000 naira (US$ 312.50–937.50). Thus, a lot of resources could be saved by the practice of AID in Nigeria.

Even though AID has been shown to be associated with emotional and psychological consequences, such as feelings of anger, guilt, loss of self-esteem, transient impotence, and withdrawal by the husband,6 the cost-effectiveness of the procedure cannot be overemphasized, especially in a society where payments for health services are almost entirely out-of-pocket expenses.7

With male factor infertility, which is amenable to artificial donor insemination and accounts for a significant proportion of infertility cases in Nigeria, a study of the awareness and acceptability of this technique will help in the management of such cases. This study in addition identified the sociocultural factors associated with the practice of AID in our environment.

Materials and methods

The study was carried out in the gynecology clinics of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, and the Enugu State University Teaching Hospital, Parklane, Enugu, and included a questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey of consecutive clients attending the infertility clinics of the above two hospitals between April 1, 2012 and January 31, 2013. All consenting couples accessing care at the infertility clinics of these hospitals and who had completed infertility investigations were included in the study. Using an acceptability rate of 19.6%5 obtained in a previous study from Yaoundé, Cameroon, at a confidence level of 95% and an error margin of 5%, the calculated minimum sample size was 242. However, a sample of 400 was used for the study.

Following individual couple counseling of eligible participants, structured and pretested questionnaires were administered to consenting couples by trained medical interns. For husbands who did not attend with their wives on the first visit, the questionnaires were administered to the husbands during subsequent evaluation of the couples. The questionnaires were administered to the husbands in a separate room from their spouses. For the couples who came together on the first visit, the questionnaires were usually administered at the same time but in separate rooms. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the institutional review board of University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu.

Data collected included the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents, including their age, tribe, level of education, and occupation. Other information sought included the awareness and acceptability of AID as well as sociocultural factors that could affect the acceptability of AID, such as cultural taboos, perception of the technique as shameful, and religious bias. Further, information on the type of infertility, observed cause of infertility, and duration of infertility was obtained from the case notes.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was both descriptive and inferential at the 95% confidence level using the Statistical package for the Social Sciences software version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Variables such as the acceptability rate of AID by individual couples, the proportion of female respondents with a duration of infertility of ≤5 years and >5 years who would accept AID, and the proportion of female respondents with primary and secondary types of infertility who would accept AID were compared with Pearson’s chi-square test and the relationships expressed using odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) in binary logistic regression analysis. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acceptability of AID by female respondents was defined as willingness of the woman to receive donor semen insemination in order to achieve pregnancy when indicated, while acceptability by male respondents was defined as willingness of the man to give consent for the spouse to receive donor semen insemination in order to achieve pregnancy when indicated. A total of 223 infertile couples were seen in the infertility clinic during the study period. All these couples were approached to participate in the study but only 200 consented to participate. Of 400 questionnaires administered to 200 consenting couples, 384 were returned correctly completed, giving a response rate of 96%. Sixteen questionnaires, eight each for male and female respondents, were excluded due to missing data.

Results

The mean age of the respondents was 39±7.8 (range 20–59) years. The mean age of the male and female respondents was 43.7±5.5 (range 28–59) years and 35.8±4.3 (range 20–46) years, respectively. The majority (74.5%, n=143) of the female respondents were in the 30–39-year age category, while 50% (n=96) of the male respondents were in the 40–49-year age category. All respondents were Christians and most (95.1%, n=365) were of the Igbo tribe. Forty five percent (n=173) of respondents had tertiary level education; 49% (n=94) and 41.1% (n=79) for the female and male respondents, respectively. Further details of the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents |

Primary infertility accounted for 37% (71/192) of the cases while secondary infertility was responsible for 63.0% (121/192). The duration of infertility was less than 5 years in 123 (64.1%) of the couples while the remaining couples (69, 35.9%) had been infertile for 5 years or more. Male factor infertility alone accounted for 33.3% (64/192) of cases, female factor infertility for 35.4% (68/192), combined male and female factor infertility for 11.5% (22/192), and unexplained infertility for 19.8% (38/192).

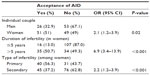

Overall, 46.6% (179/384) of the respondents were aware of AID while 53.4% (205/384) were not. Specifically, 100 of 192 females (52.1%) were aware of AID, while 79 of 192 males (41.1%) were aware (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.04–2.33; P=0.03). Of the 179 respondents who were aware of AID, the source of information was friends or colleagues (50.3%, n=90), electronic media including the Internet (16.8%, n=30), other infertile persons (12.3%, n=22), print media (8.4%, n=15), health workers (6.7%, n=12), or seminars (5.6%, n=10). Forty-three percent (77/179) of the respondents who were aware of AID expressed willingness to undertake the procedure if indicated, while 53.1% (95/179) were unwilling to accept it. The difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.66; 95% CI 0.44–1.00; P=0.05). The remaining 3.9% (n=7) of respondents were indifferent. Women (51%, 51/100) were significantly more likely than men (32.9%, 26/79) to accept the procedure (OR 2.12; 95% CI 1.15–3.91; P=0.02). Among the women, the acceptability rate was significantly higher in those with infertility of more than 5 years’ duration and in those with primary infertility (P<0.05). Details are shown in Table 2.

The major reasons why 95 respondents rejected AID were religious beliefs (34.7%, n=33), cultural taboos (17.9%, n=17), fear of contracting an infection (17.9%, n=17), fear of possibility of failure (12.6%, n=12), fear of side effects (7.4%, n=7), perception of the technique as shameful (6.3%, n=6), and probable exorbitant cost (3.2%, n=3).

Discussion

The level of awareness and acceptability of AID among infertile couples in Enugu, Nigeria, is low despite the educational level of the respondents and their duration of infertility. This is worrisome in a society where male factor infertility alone accounts for about one third (33.3%) of the total burden of infertility, as found in this study. The fact that 50.3% of the respondents who were aware of AID got information about it from their friends or colleagues and only 6.7% from health workers implies that health care professionals caring for our infertile couples do not seem to be providing them with information in this regard. The higher awareness rate identified in this study in comparison with a previous study from Yaoundé, Cameroon in 19925 may be attributable to increasing advancements and access to information technology in recent times. The peak incidence of infertility in this study was in the 30–39-year age category (74.5%) for female respondents. The increased incidence of infertility in older women has been shown to be primarily attributable to a decline in infertility rate with advancing age.8 This finding is similar to the incidence reported in a previous study from the same area.2 The high level of educational attainment observed in this study, where a majority of the respondents had tertiary education, may explain the fact that the well-educated are more likely to access medical health care services particularly for infertility issues.2 This is in contrast with the poorly educated who commonly attribute infertility to “a curse by the ancestral gods” and often visit traditional native doctors for solutions.2,9

The women demonstrated a significantly higher rate of acceptability of AID than the men, probably because they are the ones who bear more of the sociocultural and psychological brunt of infertility in any traditional African society, Nigeria inclusive.9,10 In fact, an infertile woman in our environment is often denied inheritance of her spouse’s property by the family clan upon his demise.9 Therefore, it is not surprising in this study that women whose infertility has lasted more than 5 years and those with primary infertility were more likely to accept AID.

Health education and public enlightenment of infertile couples regarding the safety of AID would help to dispel the current misconception about AID noted in this report. Enlisting the services of religious leaders in the campaign is advocated because of the level of religious bias against acceptance of the procedure in our environment. The sociocultural factors noted in this study, including religious bias, cultural taboo, and perception of the technique of AID as shameful, are in agreement with previous studies on AID and artificial reproductive technology.4,5,10

The limitation of this study is that the willingness to accept AID was assumed to mean acceptance of AID. It is thus likely that some of the respondents who did not have male factor infertility might have responded differently if their infertility were actually due to the male factor. However, the effect of this limitation on the study’s estimates is likely to be minimal given that an earlier study found intention or willingness to be associated with the actual behavior of people, including uptake of infertility treatment and immunization services.11 Another major limitation is that this study was “hospital-based” and as such limits generalization to the entire population. Only infertile couples who have been duly referred to the infertility clinic by their attending physicians are seen at the infertility clinics of these hospitals. Further, since only infertile couples who were able to complete all the infertility investigations were selected for the study, it is likely that these couples were of higher social class and educational level, given that payments for maternal and neonatal services are almost entirely out-of-pocket expenses in our environment. Selection of respondents for this study was consecutive, considering the short study period, so selection bias cannot be ruled out; a longer study period and use of probability sampling would have been more appropriate.

In conclusion, awareness and acceptability of AID is poor among infertile couples in Enugu, Nigeria. Health education and public enlightenment may help to dispel the current misconceptions regarding the safety and effectiveness of AID in our environment.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Nwafia WC, Igweh JC, Udebuani IN. Semen analysis of infertile Igbo males in Enugu, Eastern Nigeria. Niger J Physiol Sci. 2006; 21(1–2):67–70. | |

Ugwu EO, Onwuka CI, Okezie OA. Pattern and outcome of infertility in Enugu: the need to improve diagnostic facilities and approaches to management. Niger J Med. 2012;21(2):180–184. | |

Chukudebelu WO. The male factor in infertility – Nigeria experience. Int J Fertil. 1978;23(3):238–239. | |

Onah HE, Agbata TA, Obi SN. Attitude to sperm donation among medical students in Enugu, south-eastern Nigeria. J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;28(1):96–99. | |

Savage OM. Artificial donor insemination in Yaoundé: some socio-cultural considerations. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35(7):907–913. | |

Berger DM, Eisen A, Shuber J, Doody KF. Psychological patterns in donor insemination couples. Can J Psychiatry. 1986;31(9):818–823. | |

Ugwu EO, Dim CC, Okonkwo CD, Nwankwo TO. Maternal and perinatal outcome of severe pre-eclampsia in Enugu, Nigeria after introduction of magnesium sulfate. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14(4):418–421. | |

Dunson DB, Baird DD, Colombo B. Increased infertility with age in men and women. Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;103(1):51–56. | |

Ekwere PD, Archibong EI, Bassey EE, Ekabua JE, Ekanem EI, Feyi-Waboso P. Infertility among Nigerian couples as seen in Calabar. Port Harcourt Med J. 2007;2:35–40. | |

Fabamwo AO, Akinola OI. The understanding and acceptability of assisted reproductive technology (ART) among infertile women in urban Lagos, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;33(1):71–74. | |

Millstein SG. Utility of theories of reasoned action and planned behaviors for predicting physician behavior: a prospective analysis. Health Psychol. 1996;15(5):398–402. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.