Back to Journals » Nursing: Research and Reviews » Volume 9

Women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care and its predictors at Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study

Authors Getenet AB , Teji Roba K, Seyoum Endale B, Mersha Mamo A , Darghawth R

Received 5 June 2018

Accepted for publication 1 December 2018

Published 31 December 2018 Volume 2019:9 Pages 1—11

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NRR.S176297

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Cindy Hudson

Agegnehu Bante Getenet,1 Kedir Teji Roba,2 Berhanu Seyoum Endale,3 Abera Mersha Mamo,1 Rasha Darghawth4

1Department of Nursing, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Arba Minch University, Arba Minch, Ethiopia; 2Department of Public Health, School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia; 3Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia; 4Business Development Officer with CARE Ethiopia and Cuso International, Monitoring and Evaluation Advisor, Harar, Ethiopia

Background: Satisfaction with intrapartum care is crucial for the well-being of the mother and newborn. It also serves as a proxy indicator for future utilization and recommendation of the facility. Conversely, little is known about women’s level of satisfaction during the intrapartum period in the Ethiopian context of a high maternal mortality ratio. As such, the aim of this study was to assess women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care and its predictors at hospitals in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods: A hospital-based, analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted in Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia from February 1 to 28, 2017. The data were collected using an interviewer-administered questioner from 398 women who delivered in the selected hospitals during the data collection period. The collected data were entered into EpiData version 3.1 and analyzed using SPSS version 22.0. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression was applied to identify the effect of each predictor on the outcome variable (satisfaction). A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results: The proportion of women who were satisfied with intrapartum care in this study was 84.7% (95% CI: 81.1, 88.2). Factors including a minimal waiting time to be seen by the healthcare provider, ample availability of emergency drugs within the hospital, not having antenatal care follow-up, having a previous experience of home delivery, planning to deliver in the hospital, and experiencing a short hospital stay after delivery were statistically and positively associated with women’s satisfaction.

Conclusion: Overall, ~85% of the women were satisfied with the service provided in the facilities. Decreasing waiting time to be seen by the healthcare providers, ensuring emergency drugs in the hospitals, advising mothers to have antenatal care follow-up, and delivering in the health facilities are crucial to improve the quality of intrapartum care.

Keywords: satisfaction, intrapartum care, labor, hospitals, Ethiopia, delivery care, predictor

Introduction

Labor is a critically dangerous time for women and newborns. On an annual basis, nearly half a million women die during pregnancy and birth worldwide.1 There is a great disparity in maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in developing and developed countries of 239 and 12 per 100,000 live births, respectively.2 One target under the sustainable development goals plans to reduce global MMR to <70 per 100,000 births, with no country to have an MMR of more than twice the global average.3 Although Ethiopia showed a significant reduction in MMR over the past 3 decades, MMR is still 412/100,000 live births, which is very far from the international target.2,4

Similar to most developing countries, the causes of maternal deaths in Ethiopia are mainly attributed to three delays that produce a detrimental domino effect. These include a delay in seeking care, delay in reaching appropriate care, and delay in receiving care.5 Although there has been an improvement in Ethiopia health facility delivery and labor attended by a skilled birth attendant (SBA), they remain at minimum usage at 26% and 28%, respectively. A growing body of literature has considered intrapartum care satisfaction as a critical point of intervention to mitigate high MMR rate.4,6,7 In particular, WHO emphasizes ensuring women’s satisfaction as a means of secondary prevention of maternal mortality. WHO promotes births attended by SBA as a means of reducing maternal mortality and recommends that women’s satisfaction must be assessed to improve the quality and effectiveness of healthcare provided to them.8

Satisfaction with intrapartum care reaches 75% in most developing countries.9 Displeasure mainly comes from the physical characteristics of the facility, technical aspects of care, caregiver and client interaction, inadequate pain control during labor, and outcome of labor.9–13

Previous studies showed that ~50% of women were dissatisfied by hygiene and sanitary problems of the hospitals, lack of access to toilets, lack of privacy in labor rooms, distance to the health facilities, and the high cost paid for the service.14–16 Studies have also made it apparent that women’s previous negative experiences with health facility birthing care lead to underutilization in the future.17 Moreover, dissatisfaction during the intrapartum period complicates the postpartum period that results in abnormal puerperium.18

Therefore, exploring women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care and its predictors is vital both to improve the quality of labor care and rates of health-seeking behaviors of women. To adopt and implement evidence-based practice in labor care, collecting and acting on feedback received from those receiving labor care is the basis for improvement. Furthermore, nurses and midwives working in labor room will use the findings of this study as a yardstick to improve the quality of care given to laboring mothers. Despite having many studies done elsewhere, there is a scarcity of data concerning women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care in Ethiopia, with a noticeable gap in studies in Eastern Ethiopia. Therefore, this study assessed women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care and identified its predictors using quantitative research methods in hospitals in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A hospital-based, cross-sectional study was conducted from February 1 to 28, 2017, in Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia. Harar is located 526 km Northeast from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Based on the 2007 census projection, the total population of Harari Regional State was 232,000, of which females account for 115,230.19 Harar town has 19 kebeles (lowest administrative unit), which are divided into six districts. In the region, there were 7 hospitals (2 public, 2 private, 1 non-governmental, 1 police hospital, and 1 army hospital), 8 health centers, and 26 health posts. The antenatal care (ANC), health facility delivery, and SBA coverage of the region reached 75.9%, 50.2%, and 51.2% respectively.4

Study population

Women who visited the selected Harar hospitals for labor service during the data collection period were included. Women who were critically ill, had a diagnosed mental illness, and unable to communicate were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

The sample size for this study was determined using a single population proportion formula with P=0.619 (proportion of mothers satisfied with delivery care in the Amhara region referral hospitals),14 level of significance 5% (α=0.05), the margin of error 5% (d=0.05), and 10% non-responses rate. Thus, a total sample of 398 delivering mothers participated in this study.

Sampling procedure

In Harar, four hospitals were selected. Two government hospitals (Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital [HFSUH] and Jugal Hospital) and two private hospitals (Harar General Hospital and Yemage Hospital) were selected purposively based on service provision to the public and provision of basic obstetrics and newborn care. The total sample size was then allocated proportionally to each hospital by reviewing the number of deliveries attended in the last quarter of the previous year. The data were collected consecutively from each postnatal woman who received labor care in these hospitals until the desired sample size was achieved.

Data collection tool

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was developed in English, translated to Amharic and Afaan Oromo (local languages) and back to English by an independent language expert to ensure its consistency. The tool consisted of four sections regarding sociodemographic characteristics, obstetrics characteristics, health facility-related characteristics, and components of intrapartum care satisfaction. Satisfaction assessment tools were adopted from the Donabedian quality assessment framework,20 and it was assessed by 17 items (Cronbach’s alpha =0.983) across three aspects of care: accessibility and physical environment of the facility (5 items), interpersonal aspect of care (4 items), and technical aspects of care (8 items). To ensure the validity of the data collection tool, a pre-test was done on 20 postnatal women at HFSUH 1 month prior to data collection.

Data collectors and data collection procedure

Four diploma midwives and two BSc midwives who are fluent in Amharic and Afaan Oromo and did not work in the study sites were recruited as a data collector and supervisor. A 2-day training covering theoretical and practical components of data collection was held. Furthermore, data collectors were also briefed on each question included in the data collection tool. The data collection was conducted in an exit interview in the hospital. Women who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate were interviewed an average of 30 minutes in a private setting after discharge from the postnatal ward. On-site supervision was carried out during the whole period of data collection on a daily basis by the supervisors and investigators.

Operational definition

A five-point Likert scale was used for each component of satisfaction items. The overall cutoff for patient satisfaction was determined based on previous studies conducted in Ethiopia. Those who were satisfied with ≥75% of the items were categorized as “satisfied”.21

Data processing and analysis

Data were checked visually by the investigators and were coded, entered, and cleaned using EpiData version 3.1 software, and then exported to SPSS version 22.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics such as simple frequencies, measures of central tendency, and measures of variability were used to describe the characteristics of participants. The information was then presented using frequencies, summary measures, tables, and figures.

During analysis, the responses of “very satisfied” and “satisfied” were classified as “satisfied”. Responses of “very dissatisfied”, “dissatisfied”, and “neutral” were classified as “unsatisfied”. Neutral responses were classified as dissatisfied bearing in mind that they may signify a fearful way of articulating dissatisfaction. This is likely because the interview was conducted in the hospitals and women may have been reluctant to express their dissatisfaction in the services they received.14

A bivariate analysis with a crude OR (COR) of 95% CI was used to assess the degree of association between each independent variable and the outcome variable by using binary logistic regression. Independent variables with a P-value of ≤0.25 were included in the multivariable analysis to control confounding factors. Multicollinearity was checked to see the linear correlation among the independent variables by using the variance inflation factor (VIF) and standard error (SE). Variables with a VIF of >10 and an SE of >2 were dropped from the multivariable model. Hosmer–Lemeshow’s test was found to be insignificant (0.600), and Omnibus tests were significant, which indicate that the model was fitted. An adjusted OR (AOR) with 95% CI was estimated to identify the predictors associated with women’s satisfaction using multivariable logistic regression analysis. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Before beginning any part of the study, ethical clearance was issued by the Institutional Health Research Ethical Review Committee of the College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University. An official letter was written to Harari region hospitals, and permission was secured from the necessary hospital administrators. Moreover, this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki,22 and participants were informed of the purpose of the study. Furthermore, participants were well-versed about the minimal risk associated with participating in this study. In addition, before the commencement of data collection, written informed consent was obtained from literate participants and verbal informed consent from participants who were illiterate. To maintain the confidentiality of information gathered from each study participant, code numbers were used throughout the study.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

In this study, 398 study participants were involved, with a response rate of 100%. The mean (±SD) age of the study participants was 26.79 (±5.92) years. Nearly half of the participants (47.7%) were found within the age group of 25–34 years. 63.8% of the study participants were Oromo by ethnicity and 80.2% were Muslims. Nearly 98.5% were married and 72.6% were homemakers. 55% of the respondents were from urban areas (Table 1).

Obstetrics characteristics

Two hundred thirty-four (58.8%) were pregnant for the first time at the age of 19 years and above. Two hundred sixty-eight (67.3%) of women were multipara. Of them, 92 (34.3%) had one or multiple previous home deliveries. Among multipara women, 57 (21.3%), 37 (13.8%), and 58 (21.6%) had a history of neonatal death, stillbirth, and abortion, respectively. Three hundred six (76.9%) of the participants had ANC follow-up for the current pregnancy, out of which 170 (55.6%) had four or more ANC visits. Two hundred forty-eight (62.3%) of women had a plan to deliver in the hospital. The current pregnancy was wanted for most of the participants at 93.7%. Labor persisted for 12 hours or longer for 153 (38.4%) of the participants. Nearly half (48.5%) of the participants were attended by female healthcare providers (HCPs). Of the participants, an episiotomy was done for 122 (30.7%). Twenty-six (6.5%) women and 29 (7.3%) of newborns experienced complications and 22 (5.5%) newborns died.

Labor and birthing care are free for the majority, 338 (84.9%) of the participants. The prescribed drugs were available in the hospital for 351 (88.2%) of the study participants. 91.5% of the participants were seen by the HCP within 15 minutes. Of the participants, 364 (91.5%) of them were willing to visit the facility again at the time of their next pregnancy and recommend it to their relatives and neighbors (Table 2).

| Table 2 Obstetrics characteristics of study participants (n=398) at Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia, 2017 Abbreviations: ANC, antenatal care; HCP, healthcare provider. |

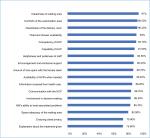

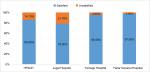

Women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care

The proportion of women who were satisfied with intrapartum care was 84.7% (95% CI: 81.1, 88.2). Three hundred seventy-five (94.2%) of the participants were satisfied with the hospital environment, 343 (86.2%) were satisfied with the technical aspect of care, and 305 (76.6%) were satisfied with the interpersonal aspect of care. Among the items used to assess intrapartum care satisfaction, explanation about the treatment given-related satisfaction (301 [75.6%]), privacy-related satisfaction (302 [75.9%]), and space adequacy-related satisfaction (330 [82.9%]) were the first three least values (Figure 1). There is a significant difference (X2=10.4 and P-value=0.01) in satisfaction among women who delivered at private and public hospitals. Satisfaction varied among hospitals; 85.9%, 78.3%, 95.5% and 97.0% of women were satisfied with the service they received at HFSUH, Jugal, Yemage and Harar General Hospital (Figure 2) respectively.

| Figure 1 Proportion of women (n=398) satisfied with major dimensions of care in Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia, 2017. Abbreviation: HCP, healthcare provider; HW, health workers. |

| Figure 2 Women (n=398) satisfied with intrapartum care in Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia, 2017. Abbreviation: HFSUH, Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital. |

Predictors of women’s satisfaction

Those variables with a P-value of ≤0.25 in the bivariate analysis were entered into multivariable analysis using the enter method to identify the independent predictors of women’s satisfaction. Participants who had no formal education were twice as likely to be satisfied compared to those who had either a secondary school education or higher (AOR =2.4, 95% CI: 1.10, 5.10). Women who did not attend ANC follow-up were four times more likely to be satisfied with intrapartum care compared to those who had ANC follow-up (AOR =3.9, 95% CI: 1.54, 9.93). Similarly, participants who had an experience of home delivery for the previous pregnancy were nine times more likely to be satisfied with birthing and labor care provided in the hospitals (AOR =9.1, 95% CI: 2.50, 23.71).

Participants who planned to deliver in the hospital were three times more likely to be satisfied than those who were referred from other health institutions (AOR =2.9, 95% CI: 1.47, 5.8). Similarly, availability of the prescribed drugs within the hospital pharmacy was associated with women’s satisfaction. Women who received the prescribed drugs from the hospital pharmacy were three times more likely satisfied compared to those who did not receive them (AOR =2.73, 95% CI: 1.24, 6.03).

Participants who waited for 15 minutes or less to be seen by the HCPs were 2.5 times more likely satisfied compared to women who waited for >15 minutes (AOR =2.50, 95% CI: 1.03, 6.17). Women who were discharged within 24 hours after delivery were two times more likely satisfied compared to those who stayed for >24 hours (AOR =1.89, 95% CI: 1.04, 3.55) (Table 3).

Discussion

Nearly 85% of women were satisfied with intrapartum care. More than three-quarters of women were satisfied with the interpersonal aspect of care. Independent predictors of women’s satisfaction were as follows: not having a formal education, not having ANC follow-up, having a previous experience of delivering at home, having a plan to deliver at the hospital, adequate availability of drugs, experiencing a short waiting time to be seen by the HCP, and a short hospital stay after delivery.

In this study, overall women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care was 84.7% (95% CI: 81.1, 88.2). This finding is slightly higher than studies conducted in referral hospitals in the Amhara region of Ethiopia (61.9%), Nepal (56%), Kenya (56%), Senegal (56.3%), Eritrea (20.8%), Bahir Dar (74.9%), St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC), Addis Ababa Ethiopia (19%), and Gamo Gofa Zone, southern Ethiopia (79.1%). However, it is lower than studies conducted in Arba Minch (90.2%) and Kenya (96% in public hospitals and 98% in private hospitals).11,14,23–30 This difference may be due to some improvements in the healthcare systems as the Ethiopian government has invested heavily in improving maternal and newborn health. It can also be due to difference in the quality of services, mothers level of expectation, or the type of health facilities (ie, this study also includes private hospitals). Additionally, currently, there are many hospitals receiving foreign investment, which has shown improvements in service quality through capacity building and equipment support. In addition, it could be due to methodological difference that some of the studies used factor analysis to set the cutoff point for satisfaction, which inflates the level of satisfaction.

There is a statistical difference (P-value =0.01) in satisfaction among women who delivered at private (96.4%) and public (82.8%) hospitals. This is in line with the comparative study conducted in Kenya.28 This is likely due to the fact that in private hospitals, services are relatively expensive and accessible to those of a higher socioeconomic status. As a result, there is a less chance of overcrowding with more attentive service delivery due to the lower doctor to patient ratio. Critically, students are not assigned for their practical internships in these hospitals, which is a major contributing factor for client dissatisfaction.

Higher educational attainment was negatively associated with women’s satisfaction in studies conducted in both Ethiopia and Serbia.15,16,27 Similarly, in this study, women who had no formal education were two times more likely to be satisfied compared to those who attended a minimum of secondary education. This might be due to the expectation of care perceived by the mother, awareness of the healthcare service provided in hospitals and communities’ standard of living.

Recent literature has shown that women who do not attend ANC follow-up are more likely satisfied with labor care given in the hospitals.16,24,27 Similarly, in this study, women who did not have ANC follow-up were four times more likely to be satisfied with intrapartum care compared to women who attended ANC follow-up. The probable reason might be that the exposure to facilities through ANC increases the understanding of women about the service provided by the HCPs. This, in turn, demands enhanced healthcare services and better-quality labor care in the hospitals or health centers.

In this study, participants who had previous experience of home delivery were nine times more likely to be satisfied with intrapartum care. This is supported by a cross-sectional study conducted in Ethiopia.16 This could be due to the fact that most of the study participants from rural areas have a previous experience of one or multiple home deliveries and as a result; they satisfied with the minimum standard of care. Thus, when the women’s childbirth process is attended by HCPs with empathy and good bedside manner; they develop trust and satisfied with the service provided.

Having the plan to deliver at the hospital was significantly and positively associated with women’s satisfaction. This finding is similar to the studies conducted in Ethiopia and other developing countries.14,21,23 This might be due to the community’s attitude toward institutional delivery, previous birth experience, recommendation by others, and birth preparedness and complication readiness.

Availability of drugs and/or supplies within the hospital were positively associated with women’s satisfaction in studies conducted in developing countries.13,31 Similarly, in this study, availability of the prescribed drugs within the hospital pharmacy was associated with women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care. This is likely due to the expensiveness the drugs when purchased outside of the hospital pharmacy.

Experiencing a short waiting time was significantly associated with women’s satisfaction. Women who wait 15 minutes or less were three times more likely to be satisfied compared to those who waited for >15 minutes. This is aligned with studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia and Nepal.14,25,27 This is most probably associated with the perception of women receiving service immediately after reaching the hospital. Furthermore, a delay in care secondary to higher number of clients, lack of human power and supplies, and time wastage in taking out clients’ card is the source of complaint in most health facilities of Ethiopia.

A short length of stay within the hospital after receiving service was also a predictor of women’s satisfaction. Women who were discharged within 24 hours after delivery were three times more likely to report being satisfied compared to those women who stayed for >24 hours. This is contrary to the study conducted in Laos.32 This may be due to the scratchy environment of the hospital and the restrictions imposed on the family in entering the labor room.

Generally, the study assessed women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care and identified its predictors. As such, this study can be used as a gap analysis and can be mobilized by health institutions to provide better patient-centered care. The strength of the study was the short time period between labor and data collection, and hence women clearly remembered their birth experience, which strengthens the data collection process by minimizing recall bias. Nevertheless, the study faced some limitations. For example, generalization to all health facilities in Harar was not possible because the data collection was restricted to the labor experience of women in hospitals. Additionally, the study may have been prone to social desirability bias, as the interview took place within the hospital setting and subjects might refrain from expressing their dissatisfaction.

Conclusion

In general, 85% of women were satisfied with the intrapartum care provided in the hospitals. Independent predictors of satisfaction with intrapartum care included the following: having a lower educational status, a plan to deliver in the hospital, not having ANC follow-up, having a previous experience of home delivery, adequate availability of drugs, a minimal waiting time to be seen by the HCP, and a short length of hospital stay after delivery. Subsequently, multidisciplinary participation is needed to improve the quality of intrapartum care.

Since patient satisfaction is central to quality of care, the HCPs put their maximum effort to meet the minimum standard of care. Considering patient-centered care as a drain to engage women in facility delivery is important to increase the rate of institutional delivery. Particularly, nurses and midwives working in labor, delivery, and other maternal and child health units should apply evidence-based nursing standards such as nursing process, which is central to the improvement of client satisfaction and quality of care. They should also give timely care with an adequate explanation of the service they provide to women.

Furthermore, the involvement of hospital administrators, regional health bureaus, and national ministry of health is forceful to make the hospital more comfortable for clients. Since satisfaction is multidimensional, further studies are needed to identify independent predictors for women’s satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the College of Health and Medical Sciences at Haramaya University and the Ministry of Education of Ethiopia for their financial support. Our appreciation also goes to the staff of Harari region hospitals for their cooperation by providing us with secondary data. Finally, we would like to appreciate our data collectors, supervisors, questionnaire translators, and study participants; without them, the research would not be possible.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

WHO. True Magnitude of Stillbirths, Maternal and Neonatal Deaths are Underreported. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. | ||

World Health Organization. UNICEF, WHO, The World Bank, United Nations Population Division. The Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Levels and Trends in Child Mortality. Report 2015. New York, USA: UNICEF; 2015. | ||

World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, 2016-2030. New York: United Nations. 2015. | ||

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF. | ||

Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International. 2012. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. | ||

Sawyer A, Ayers S, Abbott J, Gyte G, Rabe H, Duley L. Measures of satisfaction with care during labour and birth: a comparative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):108. | ||

Kavitha P, Prasath RA, Solomon H, Tsegay L, Tsegay W, Teklit Y. Mother’s satisfaction with intrapartum nursing care among postnatal mothers in orotta national referral maternity hospital, asmara, Eritrea. Int J Allied Med Sci Clin Res. 2014;2(3):249–254. | ||

World Health Organization. Making Pregnancy Safer: In the Region of Africa. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. | ||

Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, Bhattacharyya S. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):97. | ||

Melese T, Gebrehiwot Y, Bisetegne D, Habte D. Assessment of client satisfaction in labor and delivery services at a maternity referral hospital in Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:76. | ||

Oikawa M, Sonko A, Faye E, Ndiaye P, Diadhiou M, Kondo M. Assessment of maternal satisfaction with facility-based childbirth care in the rural region of Tambacouda, Senegal. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(4):95. | ||

Handady SO, Sakin HH, Alawad AA. An assessment of intra partum care provided to women in labor at Omdurman maternity hospital in Sudan and their level of satisfaction with it. Int J Pub Health Res. 2015;3(5):218–222. | ||

Atiya K. Maternal satisfaction regarding quality of nursing care during labor and delivery in Sulaimani teaching hospital. Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2016;8(3):18–27. | ||

Tayelgn A, Zegeye DT, Kebede Y. Mothers’ satisfaction with referral hospital delivery service in Amhara Region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):78. | ||

Matejić B, Milićević Milena Šantrić, Vasić V, Djikanović B. Maternal satisfaction with organized perinatal care in Serbian public hospitals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):14:14. | ||

Amdemichael R, Tafa M, Fekadu H. Maternal satisfaction with the delivery services in Assela Hospital, Arsi Zone, Oromia Region. Gynecol Obstet (Sunnyvale). 2014;4:257. | ||

Shiferaw S, Spigt M, Godefrooij M, Melkamu Y, Tekie M. Why do women prefer home births in Ethiopia? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):5. | ||

Takács L, Seidlerová JM, Šulová L, Hoskovcová SH, Horakova S. Social psychological predictors of satisfaction with intrapartum and postpartum care – what matters to women in Czech maternity hospitals? Open Med (Wars). 2015;10(1):119–127. | ||

Ethiopia. Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census: Population Size by Age and Sex. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Population Census Commission, 2008. Available from: http://www.ethiopianreview.com/pdf/001/Cen2007_firstdraft(1).pdf. Accessed December 19, 2018. | ||

Donabedian A. An Introduction to Quality Assurance in Health Care. Oxford, USA: University Press; 2002. | ||

Bitew K, Ayichiluhm M, Yimam K. Maternal satisfaction on delivery service and its associated factors among mothers who gave birth in public health facilities of Debre Markos Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Bioed Res Int. 2015;2015(2):1–6. | ||

World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. | ||

Bazant ES, Koenig MA. Women’s satisfaction with delivery care in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009;21(2):79–86. | ||

Mekonnen ME, Yalew WA, Anteneh ZA. Women’s satisfaction with childbirth care in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, 2014: cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):528. | ||

Paudel YR, Mehata S, Paudel D, et al. Women’s satisfaction of maternity care in nepal and its correlation with intended future utilization. Int J Reprod Med. 2015;2015:783050. | ||

Tesfaye R, Worku A, Godana W, Lindtjorn B. Client satisfaction with delivery care service and associated factors in the public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, Southwest Ethiopia: in a resource limited setting. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2016;2016(3):1–7. | ||

Dewana Z, Fikadu T, G/Mariam A, Abdulahi M. Client perspective assessment of women’s satisfaction towards labour and delivery care service in public health facilities at Arba Minch town and the surrounding district, Gamo Gofa Zone, South Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):11. | ||

Okumu C, Oyugi B. Clients’ satisfaction with quality of childbirth services: a comparative study between public and private facilities in Limuru Sub-County, Kiambu, Kenya. PLoS One. 2018;13(3): e0193593. | ||

Kifle MM, Ghirmai FA, Berhe SA, Tesfay WS, Weldegebriel YT, Gebrehiwet ZT. Predictors of women’s satisfaction with hospital-based intrapartum care in Asmara public hospitals, Eritrea. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2017;2017:3717408. | ||

Demas T, Getinet T, Bekele D, Gishu T, Birara M, Abeje Y. Women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care in St Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College Addis Ababa Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):253. | ||

Bhattacharyya S, Srivastava A, Avan BI. Delivery should happen soon and my pain will be reduced: understanding women’s perception of good delivery care in India. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):22635. | ||

Khammany P, Yoshida Y, Sarker MA, Touy C, Reyer JA, Hamajima N. Delivery care satisfaction at government hospitals in Xiengkhuang province under the maternal and child health strategy in Lao PDR. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2015;77(1–2):69–79. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.