Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 11

Successful device closure of a post-infarction ventricular septal defect

Authors Choi S, Han J, Jin SA, Kim MJ, Lee J, Jeong J

Received 29 February 2016

Accepted for publication 18 April 2016

Published 6 July 2016 Volume 2016:11 Pages 927—931

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S107470

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Si-Wan Choi,* Ji Hye Han,* Seon-Ah Jin, Mijoo Kim, Jae-Hwan Lee, Jin-Ok Jeong

Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital, Chungnam National University School of Medicine, Daejeon, Republic of Korea

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Abstract: Ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a lethal complication of myocardial infarction. The event occurs 2–8 days after an infarction and patients should undergo emergency surgical treatment. We report on successful device closure of post-infarction VSD. A previously healthy 66-year-old male was admitted with aggravated dyspnea. Echocardiography showed moderate left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction with akinesia of the left anterior descending (LAD) territory and muscular VSD size approximately 2 cm. Coronary angiography showed mid-LAD total occlusion without collaterals. Without percutaneous coronary intervention due to time delay, VSD repair was performed. However, a murmur was heard again and pulmonary edema was not controlled 3 days after the operation. Echocardiography showed remnant VSD, and medical treatment failed. Percutaneous treatment using a septal occluder device was decided on. After the procedure, heart failure was controlled and the patient was discharged without complications. This is the first report on device closure of post-infarction VSD in Korea.

Keywords: heart septal defects, myocardial infarction, septal occluder device, ventricular septal defect

Introduction

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a rare but lethal complication of myocardial infarction (MI). The event occurs 2–8 days after an infarction and often precipitates cardiogenic shock.1 To avoid the high morbidity and mortality of this disorder and cardiogenic shock, patients should undergo emergency surgical treatment.2–5 In current practice, post-infarction VSD is recognized as a surgical emergency. Long-term survival can be achieved in patients who undergo prompt surgery. After successful repair, survival and quality of life are excellent, even in patients >70 years.6 Despite improved surgical techniques, patients undergoing shunt repair tend to be older, and the surgery therefore more complicated. Percutaneous device closure could be a potentially attractive early alternative. Acceptable results of percutaneous VSD device closure were recently reported.7 We report on a successful device closure of a post-infarction VSD. The patient provided written consent for publication. The patient was not enrolled in a clinical trial and did not receive any experimental treatment, hence ethical approval was not sought from the Chungnam National University Hospital institutional review board.

Case

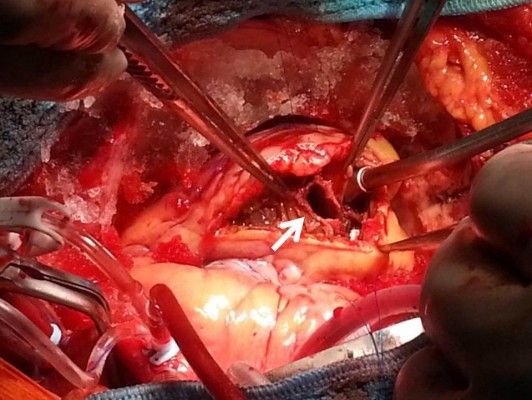

A 66-year-old male without previous history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or smoking was admitted to the emergency room (ER) due to aggravated dyspnea. Dyspnea (New York Heart Association [NYHA] III) had begun suddenly with symptoms of dyspepsia 2 days previous. On admission, the patient’s blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg and the heart rate was 96 bpm. Pansystolic murmur was heard at the apex. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed Q wave in precordial whole leads (V1–V6) and ST elevation in II, V2-6 (Figure 1). Echocardiography showed akinesia of LAD territory including left ventricular (LV) apex and mid to apical septum, anteroseptum apical lateral wall, inferior wall, anterior wall with moderate LV systolic dysfunction and muscular VSD of approximately 2 cm-size (Figure 2). We ascertained that he had a ST elevation myocardial infarction 2 days previous, with complicated VSD and heart failure. Coronary angiography performed on the day of admission showed mid-LAD total occlusion (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction, 0 flow) without collateral vessels and distal left circumflex total occlusion with antegrade collateral vessel (Figure 3). Percutaneous coronary intervention was not performed at the time due to time delay. However, emergent VSD repair surgery (two patch technique) was performed to control the left-to-right shunt with refractory heart failure (Figure 4). After the operation, he appeared stabilized. However, the cardiac murmur was heard again and pulmonary edema and pleural effusion were not controlled 3 days after the operation. Echocardiography showed remnant VSD due to highly friable septal tissue (Figure 5). The pro- B-type natriuretic peptide decreased after the operation (8,888 pg/mL at ER to 3,049 pg/mL) but elevated again (7,695 pg/mL at post-operative day 14) with diuretics. The patient’s blood pressure was 95/60 mmHg and the heart rate was 72 bpm. Although we tried to control the patient’s condition with medication, pulmonary edema was not controlled and liver enzymes were elevated due to hepatic congestion. AST/ALT level was elevated to 808/116 U/L, and total bilirubin level was elevated to 6.2 mg/dL. Therefore, we decided to treat the remnant septal defect percutaneously using the VSD occluder. On day 15, the right femoral artery and vein were cannulated under local anesthesia. The VSD was crossed from right ventricle to left ventricle through remnant VSD using a Judkin’s 5 French right catheter, and Terumo wire using a retrograde arterial approach. The VSD Occluder had a maximum size of 16 mm (AMPLATZER™ Muscular VSD Occluder device, St Jude Medical, St Paul, MN, USA). The device was placed at an appropriate site across the VSD and then released (Figure 6). Successful implantation of the device was confirmed by transthoracic echocardiography. The heart failure was controlled after device closure and the patient was discharged without complications 20 days after the procedure. At 4-month follow-up, he complained of dyspnea on exertion (NYHA II) and had improved left ventricular function without remnant shunt at the interventricular septum on echocardiography.

| Figure 1 Electrocardiography on admission. |

| Figure 3 Coronary angiogram. |

| Figure 4 Emergent operation for ventricular septal defect repair by two patch technique. |

Discussion

VSD can occur as a complication of acute myocardial infarction in approximately 1%–2% of cases in the first week.8 Surgical closure was the gold standard of this fatal complication.9 Despite improved surgical techniques, patients undergoing shunt repair tend to be older and more complicated. An interventional approach using a device is a less invasive option for these patients. However, there are currently no guidelines available for device closure of a post-infarction VSD. This is the first report on device closure of a post-infarction muscular VSD in Korea. After an initial large study by Landzberg and Lock,10 Holzer et al11 reported the immediate and midterm results of a multicenter international registry of percutaneous closure of post-infarction VSD. The AMPLATZER™ Muscular VSD Occluder device was successfully implanted in 16 of 18 patients (89%); ten of those 18 patients (56%) had undergone a previous attempt of primary surgical closure and had experienced residual shunting. The median time between MI and transcatheter closure of the VSD was 25 days. At 24 hours after closure, the residual shunt was measured: two of the 16 VSDs with successful device deployment were closed (12.5%), ten displayed trivial or small residual shunting (62.5%), and four displayed moderate or large shunts (25%). The 30 day mortality rate was 28%. Of the 16 patients, only two (12.5%) required a second procedure to close a residual VSD. According to Calvert et al,7 in a study of post-infarction VSD closure in 53 patients between eleven centers in the UK between December 1997 and January 2012, devices were successfully implanted in 89% of patients and major immediate complications included procedural death (3.8%) and emergency cardiac surgery (7.5%); 58% survived to discharge and were followed up for 395 (63–1,522) days, during which time four further patients died (7.5%). Calvert et al7 suggested that percutaneous closure of post-infarction VSD is a reasonably effective treatment for extremely high-risk patients.

There are several problems for device closure of post-infarction VSD. First, the procedure also has potential complications including device embolization, major shunting, LV rupture, and malignant arrhythmias. Even after a successful procedure, healing of the infarcted myocardium over time may increase the size of the VSD leading to device malposition and embolization. Lack of expertise of the procedure due to its rarity, leading to higher risk of complication is another problem. In addition, there are no guidelines available for device closure. Therefore, selection of candidates for the procedure is difficult.

Despite several problems, the device closure of post-infarction VSD has some benefits compared with surgical treatment, thus it can be a good alternative option to surgery. Further study will be needed in order to solve the problem of device closure and to make some improvements regarding the procedure.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a research fund of Chungnam National University.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Koh AS, Loh YJ, Lim YP, Le Tan J. Ventricular septal rupture following acute myocardial infarction. Acta cardiologica. 2011;66(2):225–230. | ||

David TE. Operative management of postinfarction ventricular septal defect. Seminars in thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1995;7(4):208–213. | ||

Gaudiani VA, Miller DG, Stinson EB, et al. Postinfarction ventricular septal defect: an argument for early operation. Surgery. 1981;89(1):48–55. | ||

Roberts JD, So DY, Lambert AS, Ruel M. Successful surgical repair of ventricular double rupture. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(6):868. e865–e867. | ||

Kuthe SA, Mohite PN, Sarangi S, Mathews S, Thingnam SK, Reddy S. Repair of postinfarct ventricular septal defect and total myocardial revascularization in a case of dextrocardia with situs inversus. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59(1):42–44. | ||

Muehrcke DD, Daggett WM. Current surgical approach to acute ventricular septal rupture. Adv Card Surg. 1995;6:69–90. | ||

Calvert PA, Cockburn J, Wynne D, et al. Percutaneous closure of postinfarction ventricular septal defect: in-hospital outcomes and long-term follow-up of UK experience. Circulation. 2014;129(23):2395–2402. | ||

Crenshaw BS, Granger CB, Birnbaum Y, et al. Risk factors, angiographic patterns, and outcomes in patients with ventricular septal defect complicating acute myocardial infarction. GUSTO-I (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries) Trial Investigators. Circulation. 2000;101(1):27–32. | ||

Lee WY, Cardon L, Slodki SJ. Perforation of infarcted interventricular septum. Report of a case with prolonged survival, diagnosed ante mortem by cardiac catheterization, and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1962;109:731–741. | ||

Landzberg MJ, Lock JE. Transcatheter management of ventricular septal rupture after myocardial infarction. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;10(2):128–132. | ||

Holzer R, de Giovanni J, Walsh KP, et al. Transcatheter closure of perimembranous ventricular septal defects using the amplatzer membranous VSD occluder: immediate and midterm results of an international registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68(4):620–628. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.