Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 14

Relationships Between Context, Process, and Outcome Indicators to Assess Quality of Physiotherapy Care in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders: Applying Donabedian’s Model of Care

Authors Oostendorp RAB , Elvers JWH , van Trijffel E, Rutten GM, Scholten–Peeters GGM , Heijmans M, Hendriks E, Mikolajewska E , De Kooning M , Laekeman M , Nijs J , Roussel N , Samwel H

Received 16 October 2019

Accepted for publication 28 January 2020

Published 2 March 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 425—442

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S234800

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Video abstract presented by Emiel van Trijffel.

Views: 561

Rob AB Oostendorp, 1–4 JW Hans Elvers, 5, 6 Emiel van Trijffel, 7, 8 Geert M Rutten, 9, 10 Gwendolyne GM Scholten–Peeters, 11 Marcel Heijmans, 4 Erik Hendriks, 12, 13 Emilia Mikolajewska, 14, 15 Margot De Kooning, 3, 16 Marjan Laekeman, 17 Jo Nijs, 3, 16 Nathalie Roussel, 18 Han Samwel 19

1Scientific Institute for Quality of Healthcare, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 2Department of Manual Therapy, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium; 3Pain in Motion International Research Group, Department of Physiotherapy, Human Physiology and Anatomy, Faculty of Physical Education and Physiotherapy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium; 4Practice Physiotherapy and Manual Therapy, Heeswijk-Dinther, the Netherlands; 5Department of Public Health and Research, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 6Methodological Health-Skilled Institute, Beuningen, the Netherlands; 7SOMT University of Physiotherapy, Amersfoort, the Netherlands; 8Department of Physiotherapy, Human Physiology and Anatomy, Faculty of Physical Education and Physiotherapy, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium; 9Institute of Health Studies, Faculty of Health and Social Studies, HAN University of Applied Science, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; 10Faculty of Science and Engineering, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands; 11Department of Human Movement Sciences, Faculty of Behavioral and Movement Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Free University Amsterdam, Amsterdam Movement Sciences, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 12Department of Epidemiology, Center of Evidence Based Physiotherapy, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands; 13Practice Physiotherapy ‘Klepperheide’, Druten, the Netherlands; 14Department of Physiotherapy, Ludwik Rydygier Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus Univerisity, Toruń, Poland; 15Neurocognitive Laboratory, Centre for Modern Interdisciplinary Technologies, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń, Poland; 16Department of Physical Medicine and Physiotherapy, University Hospital Brussels, Brussels, Belgium; 17Department of Nursing Sciences, Ph.D.-Kolleg, Faculty of Health, University Witten/Herdecke, Witten, Germany; 18Department of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Sciences (MOVANT), Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium; 19Revalis Pain Rehabilitation Centre, ‘s Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands

Correspondence: Rob AB Oostendorp

Scientific Institute for Quality of Healthcare, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, p/a Oude Kleefsebaan 325, Berg en Dal 6572 AT, the Netherlands

Tel +31 2464234219

Email [email protected]

Background: Quality indicators (QIs) are measurable elements of practice performance and may relate to context, process, outcome and structure. A valid set of QIs have been developed, reflecting the clinical reasoning used in primary care physiotherapy for patients with whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). Donabedian’s model postulates relationships between the constructs of quality of care, acting in a virtuous circle.

Aim: To explore the relative strengths of the relationships between context, process, and outcome indicators in the assessment of primary care physiotherapy in patients with WAD.

Materials and Methods: Data on WAD patients (N=810) were collected over a period of 16 years in primary care physiotherapy practices by means of patients records. This routinely collected dataset (RCD-WAD) was classified in context, process, and outcome variables and analyzed retrospectively. Clinically relevant variables were selected based on expert consensus. Associations were expressed, using zero-order, as Spearman rank correlation coefficients (criterion: rs > 0.25 [minimum: fair]; α-value = 0.05).

Results: In round 1, 62 of 85 (72.9%) variables were selected by an expert panel as relevant for clinical reasoning; in round 2, 34 of 62 (54.8%) (context variables 9 of 18 [50.0%]; process variables 18 of 34 [52.9]; outcome variables 8 of 10 [90.0%]) as highly relevant. Associations between the selected context and process variables ranged from 0.27 to 0.53 (p≤ 0.00), between selected context and outcome variables from 0.26 to 0.55 (p≤ 0.00), and between selected process and outcome variables from 0.29 to 0.59 (p≤ 0.00). Moderate associations (rs > 0.50; p≤ 0.00) were found between “pain coping” and “fear avoidance” as process variables, and “pain intensity” and “functioning” as outcome variables.

Conclusion: The identified associations between selected context, process, and outcome variables were fair to moderate. Ongoing work may clarify some of these associations and provide guidance to physiotherapists on how best to improve the quality of clinical reasoning in terms of relationships between context, process, and outcome in the management of patients with WAD.

Keywords: physiotherapy, whiplash injuries, outcome and process assessment, healthcare quality indicators, collected data

Introduction

Physiotherapists have monitored the quality of care since the 1990s. During workshops in 1992 in which the methodology of indicator development for physiotherapy was explored, the Australian Physiotherapy Association adopted the concept of quality indicators (QIs) to measure the quality of physiotherapy care.1 Around the same period, the project “Quality in Physiotherapy” was launched in the Netherlands in 1990 and resulted in the first clinical guideline “Patient Documentation” from the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF).2 Since then, similar quality reporting programs have been implemented in the United States, Canada,3 Australia and Europe, and a number of publications have been edited that address various aspects of the quality of care in general4–7 and physiotherapy in particular.8–16 The concept of clinical reasoning is central to the quality of care and has been defined as the internal mental processes that physiotherapists use when approaching clinical situations.17 This concept allows physiotherapists to generate functionally diagnostic hypotheses by acquiring information from history taking and clinical examination, linking them and comparing the result with patterns of recognition stored in long-term memory. These clinical patterns are built via the clinical learning experience, particularly repeated confrontations with similar clinical situations. However, the quality of clinical reasoning is still under discussion, and despite the increasing availability of QIs over the past decade, the use of QIs in physiotherapy is still limited.18 To date, the quality of physiotherapy remains an important topic.

A complex domain within physiotherapy is the quality of care in patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD), a condition that is often referred to as physiotherapists and remains difficult to treat. Patients with WAD (including patients with [chronic] neck pain) constitute approximately 10% fulltime equivalent of physiotherapist.19 Whiplash accident is one of the most common traffic-related injuries20 and is caused by acceleration-deceleration forces acting on the neck, head and torso.21,22 International data indicate that approximately 50% of people who encounter a whiplash accident will not recover but will continue to experience ongoing disability and pain 1 year after the accident.23,24 In addition to the poor prospects for recovery, poor treatment response is another important issue.25–27 To date, assessment and management of patients with WAD remains a significant challenge for physiotherapists.

Donabedian’s model28–30 could be a useful tool to evaluate the quality of physiotherapy in patients with WAD for two main reasons: (1) internationally it is the dominant model for evaluating quality of care,31–35 and (2) this model is used by the Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy (KNGF) for the implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs),36 and for the development of QIs for physiotherapy.9–16

Most initiatives to evaluate (improvement of) quality of care are consistent with the model proposed by Donabedian, who felt that evaluation using process, outcome and structure indicators would provide a uniform picture of the quality of care.28–30 He postulated relationships between the three constructs of process, outcome and structure, based on the idea that good structure should promote good process and good process should, in turn, promote good outcomes in a virtuous cycle. “Process” is defined as the things done to and for the patient (eg practice referrals, clinical reasoning and decision); “outcome” as the desired result of care provided by the health practitioner (eg, a patient’s functioning, and satisfaction with quality of care); and “structure” as the professional and organizational resources associated with the provision of healthcare (eg, availability of physiotherapy, equipment and staff training).28–30 Context indicators are added to the postulated relationships. Context indicators are indicators “that together constitute the complete context of an individual’s life and living, and in particular the background of an individual’s health and health-related states”.37 Context indicators have two major components: personal (eg, expectation, previous experience, preference) and environmental indicators (eg, adequate temperature, interior design, family support, and patient–physiotherapist relationship).

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that the modified Donabedian’s model has been applied to the evaluation of the relationships between context, process and outcome of clinical reasoning in patients with WAD. This study specifically aims to explore the relative strengths of the relationships of context, process, and outcome indicators in the assessment of primary care physiotherapy in patients with WAD.

Methods

Design

Details of the design and execution of this retrospective cohort study have been published elsewhere.38 In brief, in 2016 a steering group (RABO, JWHE and EvT) launched a quality improvement study on primary care physiotherapy management in WAD based on an existing dataset containing 810 patients. The main task of the steering group was to organize project management and to monitor the progress of the project. The Medical Ethics Committee of Radboud University Medical Centre Nijmegen in the Netherlands waived the requirement for ethical approval. Retrospective research based on anonymized patient files does not fall within the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act because the subject is not physically involved in the research. The data being researched are already available and not collected specifically for this project, and subjects do not have to change their behavior for this project. This study was reported in accordance with the RECORD Statement.39,40

Data Collection

Routinely collected data (RCD-WAD) in the form of pen and paper patient records were gathered over a period of 16 years (1996–2011) in two primary care physiotherapy practices in the Netherlands. The first WAD patient record was developed in 1995 and updated in both 2002 and 2009 based on national2,41,42 and international CPGs,43–46 and scientific evidence.47–49 The registration of data on oto-neurological (clinical tests) and psychological examination (observation of pain behavior and psychological questionnaires) began in 2000 and 2002, respectively, followed by the estimation of central sensitization in 2009. After cleaning and processing the dataset, the retrospective analysis of the RCD-WAD dataset started in 2016.

The relationships between context, process, and outcome indicators were computed in three steps:

Step 1. Operationalization of Donabedian’s Model

The set of quality indicators, classified per step of the clinical reasoning process,38 was reclassified by the steering group and partly reformulated, according to the modified Donabedian’s model, as context, process, and outcome variables. An expert panel, one of the most frequently employed development methods,50 was used in the selection of relevant variables for clinical reasoning QIs. An overview of the selected and non-selected context, process and outcomes variables is available in Supplementary file 1.

Context Indicators

Data on patient information, requests for care, sociodemographic characteristics, accident-related information, pre-existent functioning, pre-existent health status before accident, previous diagnostics and treatment, current health status, recovery since WAD-related accident, and previous prognostic factors were systematically noted in patient records and converted to context variables (n=30).

Process Indicators

Data on the objectives of examination, tests of musculoskeletal examination, tests of neurological, oto-neurological and psychological examination (including the use of psychological questionnaires Pain Coping Inventory [PCI]51 and Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire-Dutch Version [FABQ-DV]52,53), conclusion of diagnostic process, treatment goals per WAD-related phase, treatment in agreement with treatment goals, and side effects were also systematically noted in patient records and converted to process variables (n= 41).

The PCI is a 33-item questionnaire measuring active coping (PCI-A: 12 items [total score range 12–48]) and passive coping (PCI-P: 21 items [total score range 21–84]). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (hardly ever) to 4 (very often). PCI cut-off scores are ≥24 for active coping, and ≥42 for passive coping.

The FABQ-DV is a 16-item (no score count of 5 items) questionnaire (no score count of 5 items) measuring fear-avoidance beliefs regarding physical activities (FABQ-DV-A: 4 items [total score range: 0−24]) and work-related activities (FABQ-DV-W: 7 items [total score range: 0–42]). Items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). FABQ-DV cut-off scores are >15 at risk for pain avoiding behavior, and >34 at risk for not returning to work.

The clinimetric properties of the PCI54 and FABQ-DV53 range from acceptable to good.

Outcome Indicators

Based on recommended standard outcome measures55 and on clinimetric quality, the outcome variables consisted of a variety of patient-reported outcome measures, including measures of neck pain intensity, functioning, and global perceived effect (GPE).

Pain intensity was measured using the Visual Analogue Scale for Pain (VAS-P), which consists of a 100-mm line scored from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst imaginable pain).56,57 The cut-off score for functional recovery is VAS-P ≤30.58 Functioning-related outcome measures (ie, mobility, self-care, domestic life, work and employment) included the Neck Disability Index (NDI).59 The NDI consists of 10 questions scored 0–5 (total score range 0–50), with increasing scores representing increasing impairments and disabilities due to neck pain. The cut-off score for functional recovery is NDI ≤14.60 Finally, patients were asked to complete the GPE scale, rating the actual improvement from 1 (complete improved) to 6 (worse than ever).61 The scores of GPE were dichotomized in responders (scores 1 and 2) and non-responders (scores 3–6). The clinimetric properties of the VAS-P, NDI and GPE are rated as “good”.56,59–61

Data on pain intensity, functioning, and perceived effect, subjective evaluation, returned to work participation, treatment duration, number of treatment sessions, and reason for discharge were systematically noted in patient records and converted to outcome variables (n=14).

Structure Indicators

The number of physiotherapy practices and participating physiotherapists, and the physiotherapist’s characteristics (age, gender, clinical experience and specialized experience) were noted as structure variables.

The number of physiotherapists in the Netherlands is relatively high (n=14,000; one physiotherapist per every 1300 people). Ninety percent of the physiotherapists practice in primary care practices and 10% in multiprofessional settings of rehabilitation centers or hospitals. Manual therapy is a post-graduate specialism within physiotherapy (manual physiotherapy) at the master’s level and has a long tradition among Dutch physiotherapists. Most manual physiotherapists (n = 3000) practice in primary care practices.

The Dutch healthcare structure of physiotherapy and the structure of the participating physiotherapy practices were not operationalized in this study.

Step 2. Appraisal of Indicator Variables by a User Panel

The phases of development of QIs have been extensively described and recently published.38 In summary, a systematic RAND-modified Delphi method, including independent expert comments (n=27) and iterative feedback, was used to develop a set of recommendations suitable for transcription into QIs. The method of QI development included five steps: (1) extraction of recommendations from literature and guidelines, (2) transformation of recommendations into indicators, (3) appraisal of a preliminary set of indicators by an expert and user panel, with consensus, (4) classification of process indicators, and (5) classification of outcome indicators.

The detailed selection of the context, process, and outcome variables was appraised using two rounds of online surveys of an independent user panel (n=8) that included physiotherapists specialized in clinical reasoning in musculoskeletal physiotherapy, particularly WAD. To be considered an expert, a minimum of 5-year clinical experience was required in the management of patients with WAD. In round 1, the experts selected 62 of 85 (72.9%) variables as “relevant” (3-point Likert scale: [1] relevant; [2] possibly relevant; [3] not relevant) to the clinical reasoning process (context variables: 18 of 30 [60.0%]; process variables: 34 of 41 [82.9%]; outcome variables: 10 of 14 [71.4%]). The results were discussed in the steering group using a consensus criterion of “relevant” to clinical reasoning. In round 2, the experts were asked to score the relevant variables of the context, process, and outcome indicators on a 6-point Likert scale (6 = definitely relevant; 5 = probably relevant; 4 = possibly relevant; 3 = possibly not relevant; 2 = probably not relevant; 1 = definitely not relevant) for relevance to clinical reasoning. The experts rated 34 of 62 [54.8%] variables as definitely or probably relevant (context variables: 9 of 18 [50.0%]; process variables: 18 of 34 [52.9%]; outcome variables: 7 of 10 [70.0%]). We anticipated that this procedure would produce a highly relevant set of selected variables for the context, process, and outcome indicators of clinical reasoning.

Step 3. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize data on the patient population, and on selected context, process, and outcome variables.

Using zero-order, Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rs) was utilized to explore the associations between selected context and process variables, between selected context and outcome variables, and between selected process variables and outcome variables. The expectation was that the association between selected variables in the underlying population of patients with WAD would be “moderate”. The following criteria were used to indicate the strength of association: 0.00 to 0.25 weak association; 0.25 to 0.50 fair association; 0.50 to 0.70 moderate association; 0.70 to 0.90 substantial association; and >0.90 perfect association.62 In this study, 0.25 was considered a cutoff point (explained variance: R2 x 100 = 6.3%). For all associations, P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The analytical software program Statistix 9 was used to generate descriptive statistics.

Results

Step 1. Operationalization of Donabedian’s Model

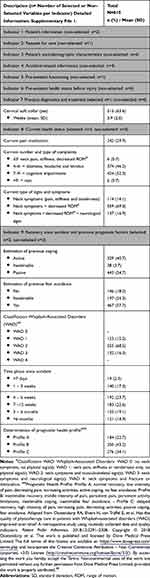

Types of indicator were classified as either context indicators (n=9), process indicators (n=9), outcome indicators (n=7), or structure indicators (n=2). An overview of the indicators (n=27) is presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Overview of Context (n=9), Process (n=9), Outcome (n=7) and Structure (n=2) Indicators for Physiotherapy in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD) |

Step 2. Appraisal of Indicator Variables

Based on the expert panel scores and consensus within the steering group, a number of “definitely” and “probably” relevant variables were selected to assess possible associations.

Context Variables

Nine of 18 variables (n=9; 50.0%) were “definitely” and “probably relevant” as context variables for the process of clinical reasoning: cervical collar, current pain medication, current complaints, current signs and symptoms, estimation of coping and fear avoidance, classification WAD, time phase since WAD-related accident, and determination of health profile. Table 2 presents the selected context variables of the patient population (N=810). Detailed information on context variables is available in Supplementary file 2.

|

Table 2 Selected Variables per Context Indicator in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD) |

The most frequent WAD classification was WAD 2 (n=555; 68.5%). Based on pre-existent complaints and previous prognostic factors, 184 patients (22.7%) had health Profile A (normal recovery, low intensity of pain, decreasing pain, increasing activities, active coping and no fear avoidance), 350 patients (43.2%) showed Profile B (inestimable recovery, middle intensity of pain, persistent pain, persistent activity limitations, inestimable coping and fear avoidance) and 276 patients (34.1%) had Profile C (delayed recovery, high intensity of pain, increasing pain, decreasing activities, passive coping and fear avoidance). At the time of (re-)referral to practice, the time phase since the WAD-related accident was >3 months (chronic WAD) in 276 patients (34.0%).

Process Variables

Eighteen of 34 variables (n=18; 52.9%) were “definitely” and “probably” relevant as process variables: questionnaires PCI and FABQ-DV (n=2), phase-related treatment goals (n=8), and phase-related physiotherapy treatment modalities (n=8). Table 3 presents the selected process variables for the patient population (N=810). Detailed information on the process variables is available in Supplementary file 3.

|

Table 3 Selected Variables per Process Indicator in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD) |

Regarding the use of different coping strategies (PCI), 416 of 523 patients (79.5%) showed risk for a (partly) passive strategy, while 396 of 523 patients (75.7%) displayed a (partly) active strategy. Risk for pain avoiding behavior (FABQ-DV-A) was present in 346 of 523 patients (66.2%), and risk for no return to work (FABQ-DV-W) in 135 of 354 patients (38.1%).

Based on prior steps of clinical reasoning, phase-related treatment goals were noted in 529 of 810 patients (65.3%; range 54.9% [Phase 3b] to 82.6% [Phase 5]). Goal-related physiotherapy modalities were noted in 442 of 529 patients (83.6%; range 60.0% [Phase 4a] to 86.3% [Phase 4b]).

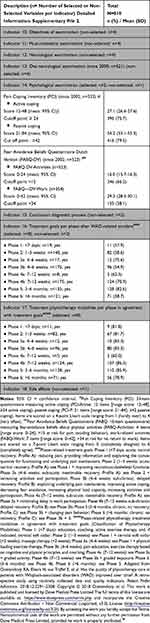

Outcome Variables

Eight of 10 variables (n=8; 80.0%) were “definitely” and “probably” relevant as outcome variables: subjective evaluation, returned to work participation, pain intensity, functioning, perceived effect, reason for discharge, duration of treatment period in months, and number of treatment sessions. Table 4 presents the selected outcome variables for the patient population (n=523). Detailed information on the outcome variables is available in Supplementary file 4.

|

Table 4 Selected Variables per Outcome Indicator in Patients with Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD) |

Patient-related outcomes were evaluated by intermediate and final interview (including evaluation of treatment goals) (n=810; 100%), and by objective outcome measurements (n=523; 64.6%). The final VAS-P score mean was 29.6 (95% CI 28.4–30.7) and 310 patients (59.3%) were functionally recovered (cut off point VAS-P ≤ 30). The final NDI score mean was 15.9 (95% CI 15.1–16.8) and 191 patients (36.5%) were functionally recovered (cut off point NDI ≤ 14). On the GPE, 241 patients (46.1%) scored in the categories “responders” (scores 1+2). On the “reason for discharge”, 241 patients (46.1%) scored “maximal” or “optimal”, while 282 patients (53.9%) scored as “minimal” or “no” result. On the “returned to work participation”, 184 of 810 patients (22.7%) returned to work without adaptations. The most frequent period for the duration of treatment was 4–6 months (n=501; 61.9%), and the most frequent number of treatment sessions was 16–20 (n=405; 50.0%).

Structure Variables of Participating Practices and Physiotherapists

Eight physiotherapists at two primary care physiotherapy practices in the South of The Netherlands collected data over a period of 16 years. The mean age of the physiotherapists (n=8) at the beginning of the study was 44.6 years (SD = 12.5), six were male (75.0%) and six were also manual physiotherapists (75.0%). The mean practice experience regarding patients with WAD was 14.4 years (SD 12.5).

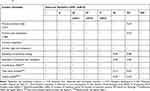

Step 3. Relationship Between Selected Variables

Spearman rank correlation coefficients (rs) are presented in Tables 5–7. The correlation coefficients for the selected context and process variables ranged from 0.27 to 0.53 (R2 7.3% to 28.1%), for the selected context and outcome variables from 0.26 to 0.55 (R2 6.8% to 30.1%), and for the selected process and outcome variables from 0.29 to 0.59 (R2 8.4% to 34.8%).

|

Table 5 Relationships Between Selected Context Variables and Selected Process Variables Expressed as Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient# |

|

Table 6 Relationships Between Selected Context Variables and Selected Outcome Variables Expressed as Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient# |

|

Table 7 Relationships Between Selected Process Variables and Selected Outcome Variables Expressed as Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient# |

Relationship Between Selected Context and Process Variables

Significant associations (p ≤0.05; rs >0.25) between selected context and process variables of treatment modalities, in agreement with phase-related goals, are presented in Table 5. Correlation coefficients ranged from 0.27 to 0.53 (R2 7.3% to 28.1%). Negative associations were found between selected context variables and physiotherapy treatment, in agreement with the phase-related goals, in phases 2 and 3b, and positive associations in phases 4b, 5 and 6. The remaining selected context variables and selected process variables showed weak associations (rs ≤0.25). No analyses were performed of selected context variables and phase-related treatment goals in phases 1, 3a and 4a (n<20).

Relationship Between Selected Context and Outcome Variables

Significant relationships (p ≤0.05; rs >0.25) between selected context and outcome variables are presented in Table 6. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.26 to 0.55 (R2 6.8% to 30.3%). Fair-to-moderate associations were found between most context variables and the duration of the treatment period and/or the number of treatment sessions as outcome variables. The selected context variables and the outcomes of pain intensity, functioning and perceived effect exhibited weak relationships (rs ≤ 0.25).

Relationship Between Selected Process and Outcome Variables

Significant relationships (p ≤0.05; rs >0.25) between selected process and outcome variables are presented in Table 7. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.29 to 0.59 (R2 8.4% to 34.8%). Moderate negative associations were found between PCI-active and the outcome measures “pain intensity” (VAS) and “functioning” (NDI), and fair to moderate positive associations between PCI-passive, FABQ-DV-Activities and FABQ-DV-Work, and “pain intensity” (VAS) and “functioning” (NDI). Phase 3 after a WAD-related accident was negatively associated with the duration of the treatment period and the number of treatment sessions. Weak relationships (rs ≤0.25) were found between phases 2, 4b, 5 and 6 after a WAD-related accident and all outcomes. No analyses were performed between phases 1, 3a and 4a and outcomes (n<20)

Discussion

We applied a systematic procedure to explore relative relationships between selected context, process, and outcome variables that reflect primary care physiotherapy practice relevant to patients with WAD. Few studies have described the disabilities of patients with WAD-related neck pain referred to a specialized outpatient clinic63 or analyzed long-lasting functional consequences after WAD-related accidents.24 To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previous study of equivalent length has described relationships among context, process and outcome indicators in patients after WAD-related accidents referred to specialist primary care physiotherapy practices. The only other similar (15-year) study was reported as the individual experience of one spinal surgeon.64

Based on a modified Donabedian’s model that good context should promote good process and good process should, in turn, promote good outcomes in a virtuous cycle, we expected moderate associations between context, process, and outcome. However, the identified associations were “fair” to “moderate” and many associations were “weak”. The most striking moderate associations were those between psychological process variables (coping, fear-avoidance) and the outcomes “pain intensity” and “functioning”, and between context variables (time since WAD-related accident and prognostic health profile) and the number of treatment sessions. A more active coping strategy and lower fear-avoidance were moderately associated with lower pain intensity and better functioning as outcomes. Passive coping strategy and more fear-avoidance beliefs were fairly to moderately associated with higher pain intensity and worse functioning as outcomes. This is in accordance with the findings of a prospective longitudinal study in patients with WAD-related injury.65 A prognostic unfavorable health profile was negatively associated with treatment goals in the first phases after a WAD-related accident and positively associated with more treatment sessions. The percentages of variance only partly explain the associations between the context, process, and outcome variables (maximum 30%). Clearly, other factors not included in the study such as injury assurance and compensation may play a role in relationships between selected context, process, and outcome variables.

Contrasting Viewpoints

Our initial expectation was that we would find a stronger association between context, process, and outcome variables. The “fair” to “moderate” associations may be due to distinctions between clinical and statistical models regarding associations between two or more variables. Clinically, variables are grouped together on a qualitative basis when combinations can be justified based on a model of clinical reasoning. Our patient record included a clinical reasoning and decision model relevant to patients with WAD and is comparable to general models such as the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians (HOAC).66,67 Statistically, variables are grouped on a quantitative basis, and in contrast to clinical approaches, statistical approaches call for decisions based on mathematical models, each with its own intrinsic logic and rationale.

In our study, context, process, and outcome variables were selected in a stepwise manner by an expert panel of eight independent physiotherapists specialized in clinical reasoning in musculoskeletal physiotherapy. “Relevance” is an important feature of the key variables of clinical reasoning, characterized by intuition and deduction. Selection was based on current professional knowledge and expertise in clinical reasoning rather than on statistical factors. Another option would be to select variables based on scientific evidence. However, currently available data do not provide an evidence-based rationale for limiting the number of variables.38,68–70 Clinical reasoning is therefore still largely based on professional consensus or standards (evidence level IV), and using an expert panel to select relevant variables, therefore, seems to be valid.50 Although this form of validity is important for establishing face validity of the indicators, consensual validity is a weak form of evidence for drawing conclusions regarding criterion-related validity.

Clinical Reasoning and Pattern Recognition

Clinical assessment of patients with WAD was used in this study for the identification of the categories of information which the participating physiotherapists have found useful for understanding and managing their patients with WAD. For instance, factors such as a patient’s sociodemographic information, accident-related information, information about recovery after the accident, a patient’s expectations, and information derived from clinical examination. All this information requires that physiotherapists apply well-organized biopsychosocial knowledge to their clinical reasoning.71,72 The participating physiotherapists were experienced in the assessment of patients with WAD, and this accumulated knowledge is stored in their memory in patterns that facilitate their communication with the patient and thinking about the patient’s problem. Recognition of patterns in WAD is probably highly developed among participating physiotherapists and is one of the cornerstones of their clinical expertise. We expected the clinical relationships to be substantial between the specialized experience of the participating physiotherapists, on the one hand, and the context variables, reflective process of clinical examination, treatment goals and content of treatment in all phases after the WAD-related accident on the other. This expectation was probably encouraged by the highly developed pattern recognition of the participating physiotherapists. It is not clear to what extent the participating physiotherapists took the PCI and FABQ-DV scores into consideration when designing the treatment plan and during treatment. It is likely that they favor their own clinical estimation above questionnaire scores. However, statistically, the associations between the clinical estimation of coping and fear avoidance as context variables and outcome variables were non-significant, while the associations between the PCI and FABQ-DV scores as process variables and outcome variables “pain intensity” and “functioning” were significant. These results support the assumption that physiotherapist’s and patient’s perception of treatment benefits is not reflected in an appreciation of a direct association between the context and process variables and the outcome variables “pain intensity”, “functioning” and “global perceived effect”. Nevertheless, pain intensity, functioning and GPE were reduced to the level of functional recovery in over half of the patients. It seems important to integrate the scores of coping, fear avoidance and fear of movement in physiotherapy treatment assessments in patients with neck pain, particularly whiplash-induced neck pain, in order to facilitate optimal treatment-related outcomes.65,73,74

There is a growing awareness that a substantial component of treatment effectiveness is determined by placebo or nocebo responses.75,76 Placebo and nocebo effects are related to contextual factors rather than the specific treatment content (eg, the approach to the patient rather than specific phase-related treatment goals and treatment). In physiotherapy, contextual factors that may induce a placebo or nocebo effect include the characteristics of the physiotherapists (eg, perceived credibility and reliability), the patient (eg, previous treatment experiences and preferences), the patient-therapist alliance (eg, mutual trust and respect), non-specific aspects of the treatment (eg, word use, patient approach) and the treatment setting (eg, interior design).77,78 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of various treatment modalities for patients with osteoarthritis demonstrated that on average 75% (range 47% to 91%) of the effect was attributable to contextual factors.79 Therefore, taking placebo and nocebo effects and the influence of contextual factors into consideration, it is possible that improved quality of clinical reasoning, leading to a higher quality of diagnostic and therapeutic process, does not immediately result in better patient-related outcomes.

Relationships Between Selected Context and Process Variables

The associations between the estimation of previous coping and fear-avoidance and treatment goals were negative in phases 2 and 3b, and positive in phases 4b, 5, and 6.

The negative association between selected context variables and the treatment goals in the first phases after a WAD-related accident (≤6 weeks) is plausible because previous negative prognostic context factors (ie, cervical collar or pain medication over a long period, and previous treatment experiences and preferences) are negatively associated with the reformulated treatment goals and the content of intervention in the early phases after a WAD-related accident. This suggests that there is probably a discrepancy between patients’ and physiotherapist’s goal setting in the acute and subacute phases after a WAD-related accident. Patients’ expectations were focused on hands-on treatment while those of the physiotherapist, keeping in mind the negative context factors and guideline-based recommendations, were focused on hands-off treatment (resulting in cognitive patient-physiotherapist dissonance). Treatment goals in the chronic phases after a WAD-related accident were more consonant between and acceptable to both patient and physiotherapist. Presumably, patient-therapist consonance increases in later phases after a WAD-related accident.80

Relationship Between Selected Context and Outcome Variables

The associations between selected context and outcome variables were non-significant. The clinical estimation of previous coping and fear avoidance, and profiles A, B and C showed no significant associations with the outcome variables “pain intensity”, “functioning” and “global perceived effect”. The only significant association was found between these selected context variables, and a longer period of treatment and a higher number of treatment sessions. A stronger association between clinical context variables and the outcome variables “pain intensity”, “functioning” and “global perceived effect” was expected, more specifically between negative prognostic factors and the outcomes “pain intensity” and “functioning”.

Prognostic factors have shifted over time in the direction of chronicity, to the prediction of delayed or no recovery of patients with WAD.65,73,74,81–86 The prevalence of chronic pain in patients with WAD, in combination with delayed recovery (sub-chronic) and no recovery (chronic), was high in our study. About half of the patients had been re-referred following previous cervical collar, pain medication and physiotherapy treatment as negative prognostic factors. Only a small number of patients were classified under ‘normal recovery, with the majority exhibiting recovery that was either inestimable, stabilized or had deteriorated at the time of referral in combination with negative prognostic factors.

As early as 2002, psychological factors such as coping and fear avoidance were expected to become more important to the clinical course of patients with WAD than mechanical factors such as impairments in the mobility of joints of the cervical spine.87,88 This led to the implementation in 2002 of the KNGF-CPG Whiplash and Physiotherapy, which includes two psychological questionnaires (PCI and FABQ-DV) as process variables.

Relationship Between Selected Process and Outcome Variables

The moderately negative associations between the PCI-A scores, and fairly to moderately positive associations between the PCI-P, FABQ-DV-A and FABQ-DV-W scores and the outcome variables “pain intensity” (VAS) and “functioning” (NDI) are an illustration of the importance of the prognostic factors “coping” and “fear avoidance” for outcomes. It is remarkable that phase-related treatment goals were weakly associated with outcomes (except the negative association of phase 3b with duration of treatment period and number of treatment sessions), suggesting that there is a weak association between goal-related modalities and outcomes. These findings are counterintuitive as it was clinically expected that phase- and goal-related treatment modalities and outcomes would be highly associated. Although the selection of process and outcome variables was in accordance with usual methods in terms of clinical relevance, the reliability and validity of the set of variables used in the present study is now under discussion. An option for further research is the investigation of the reliability and validity of the process variable “treatment goals” as an outcome variable of clinical diagnostic reasoning and as a process variable of clinical therapeutic reasoning.

The use of these questionnaires is not recommended in the current KNGF-CPG Neck Pain.68,69 We prefer to use the PCI and FABQ-DV as prognostic instruments for outcomes of pain intensity and functioning, perhaps accompanied by questionnaires on psychological functioning in relation to cognition and behavior in patients with chronic WAD.89 This is consistent with the importance of transforming the existing model of chronic pain into the clinical management of patients with chronic pain90 in accordance with the best evidence on the management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, particularly patients with neck pain and low back pain.91,92

Only a moderate-to-fair association was observed between the psychological questionnaires as selected process variables and “pain intensity” and “functioning” as outcome variables. This is probably due to a failure of outcome attribution. A possible explanation for this attribution failure is that outcomes (eg, returned to work participation) cannot be unambiguously attributed to the intervention per phase after the WAD-related accident, specifically the (sub)chronic phases. A large part of the multimodal intervention per phase consists of information and explanation about the consequences of the WAD-related accident (phases 1 and 2), and of pain education (phases 3, 4, 5 and 6). The applied educational intervention in the (sub)acute phases provides information on the accident, type of injury, symptomatology, pain physiology, prognosis for recovery, and the relevance of exercise therapy and physical activity. The focus in the (sub)acute phase is on the concept that activities do not result in further damage and therefore these activities prevent chronicity. The content of the applied educational intervention in the (sub)chronic phases consists of an extensive pain education program aimed at changing cognition and behavior. Goals include reassuring the patient, modulating maladaptive cognitions about WAD, and activating the patient. Based on a systematic review,93 available evidence for the use of pain educational sessions in the acute phase is robust. Despite the clinical plausibility of its application, an extensive pain education program during the (sub)chronic phases of WAD is not yet supported by sufficient evidence.91

It would also be reasonable to develop phase-related outcomes to prevent outcome attribution failure. This contrasts with domain-related recommendations for a core set of outcome measurements, in which six core domains of measurement after the WAD-related accident are recommended, but without distinctions per phase.94

The outcomes in our study (ie, pain intensity, functioning and GPE) seem to be suitable for the (sub)acute phases, but less suitable for the (sub)chronic phases. It, therefore, appears that the chosen outcome measurements were less suitable to the majority of patients in our study, as most were classified in (sub)chronic phases. Attribution of outcomes to the goals of the intervention in the (sub)chronic phase after a WAD-related accident could be enhanced by the relationship between process and outcome variables. The next step is to determine the outcome measurements attributed to the interventional content for the (sub)acute and (sub)chronic phases after a WAD-related accident. Psychological variables (ie, fear avoidance, fear of movement, pain cognition, pain behavior and pain catastrophizing) should be considered as candidate outcome measures in patients with persistent pain after a WAD-related accident.89

Suitability of Donabedian’s Model

Due to the absence of a professional standard for patient records, we developed a pen and paper patient record that described the steps of clinical reasoning, modeling it on the first draft of the Dutch CPG Physiotherapy Documentation in 1993,2 with update in 2011,95 and on the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders in 1995,43 and on the first draft of the Dutch CPG Physiotherapy and Whiplash in 2001.41 Guideline-based patient records typically have a positive impact on healthcare processes and outcomes,96 and high-quality patient documentation is a prerequisite for using RCD for research purposes.38

Donabedian’s model, combined with clinically relevant and context-related variables, has proven helpful in the reclassification and reformulation of patient records around clinical reasoning-related context, process, and outcome indicators, and has provided insight into the mutual associations of these indicators. The associations in our study ranged from “fair” to “moderate”. As mentioned in the introduction, we have not found comparable physiotherapy studies in patients with WAD. The relationships between process and outcome in comparable studies (for instance in stroke care,34 chronic disease management32 and diabetes networks31) were “weak” to “substantial”, depending on the constructs of variables.

Our original expectation was that the correlation coefficients between the context, process, and outcome associations would be higher. The interpretation of correlation coefficients is, therefore, an interesting point of discussion. The current internationally accepted steps of clinical reasoning for physiotherapy provides opportunities to select from a range of diagnostic and therapeutic options, and from outcomes with different constructs. Depending on the constructs of history taking (context), diagnostic tests and treatment (process) and outcome measurements (outcome), a range of features can be described, including WAD-related accident and mechanisms, time frames, body functions and structures, activities and participation, contextual factors, signs, symptoms, chronicity, behavior and expectations, treatment modalities, and last but not least, outcome measurements. Many WAD-related reviews call for further research to identify who does or does not respond to physiotherapy treatment. Currently, there is no consensus on patient assessment and management after WAD-related accident. Achieving consensus will require coordination between context, process and outcome constructs in order to determine optimal associations. The theory underlying Donabedian’s model would be a suitable platform on which to base this process of coordination.

Limitations

The principal limitations of this retrospective cohort study were that it was carried out in only two primary care physiotherapy practices in the Netherlands, and data were collected by eight physiotherapists. All patients were referred to these two practices, which were specialized in the assessment and management of patients with WAD. With the exception of a few patients with red flags, all patients were assessed in this retrospective cohort study. While the characteristics of the participating physiotherapists were comparable to the national average97 and the patient sample was comparable to participants in another Dutch study,98 the low number of participating practices and physiotherapists may have limited generalizability and thus limited the external validity of the results.

A further limitation was that while international literature on the relationships between context, process, and outcome indicators in other disciplines and settings was taken into account, the study was conducted within the confines of the Dutch healthcare and primary care physiotherapy system, and specifically within the context of the incidence and prevalence of patients with WAD in the Netherlands. This implies that the results may be more relevant to physiotherapy practice in the Netherlands and perhaps less applicable internationally. Nevertheless, although national in scope, many of the lessons learned about relationships between context, process and outcome indicators in this study will surely resonate with an international audience.

The dataset was checked in 2016 for completeness and actuality. Based on the completeness of the data regarding context, process and outcome variables (≥90%), the consistency of the pen and paper patient record was confirmed on the basis of KNGF-CPG Physiotherapy Documentation, as published in 201699 and in 2019.100 Although the pen and paper record has now been replaced by electronic patient documentation (EPD), the pen and paper record used in this study still meets the requirements of the most recent Dutch CPG Physiotherapy Documentation.100 High-quality clinical registries generally have a positive impact on healthcare processes and outcomes.96 Despite the limitations of RCD studies generally, including this RCD-WAD study, the expectation was that the results of this study could plausibly represent insights into the associations between context, process and outcome variables in clinical reasoning in patients with WAD anno 2020. In order to assess the quality of our study using the RCD-WAD, we compared the text to the criteria of the RECORD statement and found that most criteria were met.39,40

Conclusion

Bearing in mind the goals of this study as part of the project “Physiotherapy and Whiplash”, the noted selection bias affecting physiotherapists and patients, and the possible lack of external validity of the results, we can guardedly conclude that:

- Donabedian’s model was helpful when exploring the relationships between context, process, and outcome variables in the assessment and management of patients with WAD in primary care physiotherapy;

- Associations between selected context and process variables, between selected context and outcome variables and between selected process and outcome variables were fair to moderate;

- The percentages of variance can only partly explain the associations between the context, process, and outcome variables (maximum 30%). Other factors, not included in the study, may, therefore, play a role in relationships between selected context, process, and outcome variables;

- Use of valid coping- and fear-avoidance-related questionnaires instead of clinical estimation in the process of clinical reasoning is strongly recommended.

Ongoing work may clarify some of these associations and provide guidance to physiotherapists on how best to improve the quality of clinical reasoning in terms of context, process, and outcome in the management of patients with WAD.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Grimmer K, Dibden M. Clinical indicators for physiotherapists. Aust J Physiot Ther. 1993;9(2):81–85. doi:10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60471-2

2. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie. Richtlijnen voor de Fysiotherapeutische Verslaglegging (KNGF-Guidelines Physiotherapy Documation). Amersfoort: KNGF; 1993. Dutch.

3. Canadian physiotherapy association [homepage on the internet]. Available from: https://physiotherapy.ca/quality-physiotherapy.

4. Campbell S, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall M. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. In: Grol R, Baker R, Moss F, editors. Quality Improvement Research. Understanding the Science of Change in Health Care. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2004:6–28.

5. Lawrence M, Olesen F. Indicators of quality health care. Eur J Gen Pract. 1997;3:103–108. doi:10.3109/13814789709160336

6. Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15:523–530. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzg081

7. Westby MD, Klemm A, Li LC, Jones CA. Emerging role of quality indicators in physical therapist practice and health service delivery. Phys Ther. 2016;96(1):90–100. doi:10.2522/ptj.20150106

8. Grimmer K, Beard M, Bell A, et al. On the constructs of quality physiotherapy. Aust J Physio Ther. 2000;46(1):3–7. doi:10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60308-1

9. Nijkrake MJ, Keus SH, Ewalds H, et al. Quality indicators for physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2009;45(2):239–245.

10. Jansen MJ, Hendriks EJ, Oostendorp RA, Dekker J, De Bie RA. Quality indicators indicate good adherence to the clinical practice guideline on “Osteoarthritis of the hip and knee” and few prognostic factors influence outcome indicators: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46(3):337–345.

11. Rutten GM, Harting J, Bartholomew LK, Schlief A, Oostendorp RA, de Vries NK. Evaluation of the theory-based Quality improvement in Physical Therapy (QUIP) programme: a one-group, pre-test post-test pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:194. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-194

12. Oostendorp RA, Rutten GM, Dommerholt J, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Harting J. Guideline- based development and practice test of quality indicators for physiotherapy care in patients with neck pain. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19(6):1044–1053.

13. Scholte M, Neeleman-van der Steen CW, Hendriks EJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Braspenning J. Evaluating quality indicators for physical therapy in primary care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(3):261–270. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzu031

14. Peter WF, Hurkmans EJ, van der Wees P, Hendriks E, van Bodegom-vos L, Vliet Vlieland TP. Healthcare quality indicators for physiotherapy management in hip and knee osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a Delphi Study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2016;14(4):219–232. doi:10.1002/msc.v14.4

15. Gijsbers HJ, Lauret GJ, van Hofwegen A, van Dockum TA, Teijink JA, Hendriks HJ. Development of quality indicators for physiotherapy for patients with PAOD in the Netherlands: a Delphi study. Physiotherapy. 2016;102(2):196–201. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2015.06.001

16. Spitaels D, Hermens R, Van Assche D, Verschueren S, Luyten F, Vankrunkelsven P. Are physiotherapists adhering to quality indicators for the management of knee osteoarthritis? An observational study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;27:112–123. doi:10.1016/j.math.2016.10.010

17. Pelaccia T, Forestier G, Wemmert C. Deconstructing the diagnostic reasoning of human versus artificial intelligence. CMAJ. 2019;191(48):E1332–E133. doi:10.1503/cmaj.190506

18. Jette DU, Jewell DV. Use of quality indicators in physical therapist practice: an observational study. Phys Ther. 2012;92(4):507–524. doi:10.2522/ptj.20110101

19. Van den Dool J, Schermer T. Nivel Zorgregistraties. Zorg door de fysiotherapeut. Jaarcijfers 2017 en trendcijfers 2013–2017. Utrecht: Nivel; 2018.

20. Holm LW, Carroll LJ, Cassidy JO, et al. The burden and determinants of neck pain in whiplash associated disorders after traffic collisions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S61–S69. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.011

21. Davis CG. Mechanisms of chronic pain from whiplash injury. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013;20(2):74–85. doi:10.1016/j.jflm.2012.05.004

22. Elliott JM, Noteboom JT, Flynn TW, Sterling M. Characterization of acute and chronic whiplash- associated disorders. J Orthop Sport Phys. 2009;39(5):312–323. doi:10.2519/jospt.2009.2826

23. Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4Suppl):S93–S100. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816445d4

24. Bunketorp L, Nordholm L, Carlsson J. A descriptive analysis of disorders in patients 17 years following motor vehicle accidents. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(3):227–234. doi:10.1007/s00586-002-0393-y

25. Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Lin CW, et al. Comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme or advice for chronic whiplash (PROMISE): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2014;384(9938):133–141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60457-8

26. Wiangkham T, Duda J, Haque S, Madi M, Rushton A, Eldabe S. The effectiveness of conservative management for acute Whiplash Associated Disorder (WAD) II: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133415. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133415

27. Sterling M, de Zoete RMJ, Coppieters I, Farrell SF. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain. Part 4: neck pain. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):E1219. doi:10.3390/jcm8081219

28. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):691–729. doi:10.1111/milq.2005.83.issue-4

29. Donabedian A. Methods for deriving criteria for assessing the quality of medical care. Med Care Rev. 1980;37(7):653–698.

30. Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033

31. Mahdavi M, Vissers J, Elkhuizen S, et al. The relationship between context, structure, and processes with outcomes of 6 regional diabetes networks in Europe. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192599. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192599

32. Ameh S, Gómez-Olivé FX, Kahn K, Tollman SM, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Relationships between structure, process and outcome to assess quality of integrated chronic disease management in a rural South African setting: applying a structural equation model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2177-4

33. Lorini C, Porchia BR, Pieralli F, Bonaccorsi G. Process, structural, and outcome quality indicators of nutritional care in nursing homes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:43. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2828-0

34. McNaughton HJ, McPherson K, Taylor W, Weatherall M. Relationship between process and outcome in stroke care. Stroke. 2003;34(3):713–717. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000057580.23952.0D

35. Mant J. Process versus outcome indicators in the assessment of quality of health care. Int J Qual Health C. 2001;13(6):475–480. doi:10.1093/intqhc/13.6.475

36. Meerhoff GA, van Duimen SA, Maas MJM, Heijblom K, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG, Van der Wees PJ. Development and evaluation of an implementation strategy for collecting data in a national registry and the use of patient-reported outcome measures in physical therapist practices: quality improvement study. Phys Ther. 2017;97(8):837–851. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzx051

37. WHO. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

38. Oostendorp RA, Elvers H, van Trijffel E, et al. Has the quality of physiotherapy care in patients with Whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) improved over time? A retrospective study using routinely collected data and quality indicators. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2291–2308. doi:10.2147/PPA

39. Benchimol E, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The Reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885

40. Langan SM, Cook C, Benchimol EI. lmproving the reporting of studies using routinely collected health data in physical therapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46(3):126–127. doi:10.2519/jospt.2016.0103

41. Bekkering GE, Hendriks HJM, Lanser K, et al. KNGF-richtlijn Whiplash (KNGF guideline Whiplash). Ned Tijdschr Fysiother. 2001;111(Supplement):Sl–S25. Dutch.

42. Scholten-Peeters GGM, Bekkering GE, Verhagen AP, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the physiotherapy of patients with whiplash-associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27(4):412–422. doi:10.1097/00007632-200202150-00018

43. Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(8Suppl):S1–S73.

44. Leigh TA. Best Practices Task Force. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Physiotherapy Treatment of Whiplash Associated Disorders. Vancouver: Physiotherapy Association British Columbia; 2004.

45. Moore A, Jackson A, Jordan J, et al. Clinical Guidelines for the Physiotherapy Management of Whiplash Associated Disorder (WAD). London: Chartered Society of Physiotherapy; 2005.

46. TRACsa. Clinical Guidelines for Best Practice Management of Acute and Chronic Whiplash Associated Disorders: Clinical Resource Guide. Adelaide: South Australian Centre for Trauma and Injury Recovery; 2008.

47. Hurwitz EL, Carragee EJ, van der Velde G, et al. Treatment of neck pain: noninvasive interventions: results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1 976). 2008;33(4Suppl):S123–S152. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181644b1d

48. Carroll U, Holm LW, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): results of the bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S97–S107. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.014

49. Nijs J, Van Oosterwijck J, De Hertogh W. Rehabilitation of chronic whiplash: treatment of cervical dysfunctions or chronic pain syndrome? Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(3):243–251. doi:10.1007/s10067-008-1083-x

50. Yildiz Ö, Demirörs O. Healthcare quality indicators–a systematic review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(3):209–222. doi:10.1108/IJHCQA-11-2012-0105

51. Kraaimaat FW, Bakker A, Evers AMW. Pijncoping-strategieën bij chronische pijnpatiënten. De ontwikkeling van de Pijn-Coping-lnventarisatielijst (PCI). [Pain-coping strategies in chronic pain patients: the development of the Pain Coping lnventory (PCI)]. Gedragstherapie. 1997;30:185–201. Dutch.

52. Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson L, Somerville D, Main CJ. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52(2):157–168.

53. Vendrig A, Deutz P, Vink L. Nederlandse vertaling en bewerking van de fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Pijn En Pijnbestrijding. 1998;18(1):11–14.

54. Kraaimaat FW, Evers AW. Pain-coping strategies in chronic pain patients: psychometric characteristics of the pain-coping inventory (PCI). Int J Behav Med. 2003;10(4):343–363. doi:10.1207/S15327558IJBM1004_5

55. Pietrobon R, Coeytaux RR, Carey TS, Richardson WJ, DeVellis RF. Standard scales for measurement of functional outcome for cervical pain or dysfunction: a systematic review. Spine. 2002;27(5):515–522. doi:10.1097/00007632-200203010-00012

56. Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13(4):227–236. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-240X

57. Kamper SJ, Grootjans SJ, Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M. Measuring pain intensity in patients with neck pain: does it matter how you do it? Pain Pract. 2015;15(2):159–167. doi:10.1111/papr.12169

58. Scholten-Peeters GG, Verhagen AP, Neeleman-van der Steen CW, Hurkmans JC, Wams RW, Oostendorp RA. Randomized clinical trial of conservative treatment for patients with whiplash- associated disorders: considerations for the design and dynamic treatment protocol. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2003;26(7):412–420. doi:10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00092-7

59. Vernon H, Mior S. The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991;14(7):409–415.

60. Vernon H. The neck disability index: state-of-the-art, 1991-2008. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(7):491–502. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.08.006

61. Kamper SJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL, Maher CG, de Vet HC, Hancock MJ. Global perceived effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):760–766. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.009

62. Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research. Applications to Practice. Norwalk, Connecticut: Appleton & Lange; 1993:439–456.

63. Johansen JB, Røe C, Bakke ES, Mengshoel AM, Storheim K, Andelic N. The determinants of function and disability in neck patients referred to a specialized outpatient clinic. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(12):1029–1035. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31828027a2

64. McCabe E, Jadaan M, Jadaan D, McCabe JP. An analysis of whiplash injury outcomes in an Irish population: a retrospective fifteen-year study of a spine surgeon’s experience. Ir J Med Sci. 2019. doi:10.1007/s11845-019-02035-2

65. Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Menezes Costa Lda C, McAuley JH, Hush JM, Sterling M. Does fear of movement mediate the relationship between pain intensity and disability in patients following whiplash injury? A prospective longitudinal study. Pain. 2012;153(1):113–119. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.023

66. Rothstein JM, Echternach JL. Hypothesis-oriented algorithm for clinicians. A method for evaluation and treatment planning. Phys Ther. 1986;66(9):1388–1394.

67. Rothstein JM, Echternach JL, Riddle DL. The Hypothesis-oriented algorithm for clinicians Il (HOAC Il): a guide for patient management. Phys Ther. 2003;83(5):455–470. doi:10.1093/ptj/83.5.455

68. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie. KNGF-Richtlijn Nekpijn (KNGF Guideline Neck Pain). Amersfoort: KNGF; 2016. Dutch.

69. Bier JD, Scholten-Peeters GGM, Staal JB, et al. Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Phys Ther. 2018;98(3):162–171. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzx118

70. Parik P, Santaguida P, Macdermid P, Gross A, Eshtiaghi A. Comparison of CPG’s for the diagnosis, prognosis and management of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):81. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2441-3

71. Higgs J, Jones M, Loftus S, Christensen N, eds, Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann; 2008:3–18.

72. Jones MA, Rivett DA. Clinical Reasoning for Manual Therapists. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann; 2004:1–24.

73. De Pauw R, Kregel J, De Blaiser C, et al. Identifying prognostic factors predicting outcome in patients with chronic neck pain after multimodal treatment: a retrospective study. Man Ther. 2015;20(4):592–597. doi:10.1016/j.math.2015.02.001

74. Saavedra-Hernández M, Castro-Sánchez AM, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Cleland JA, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Arroyo-Morales M. The contribution of previous episodes of pain, pain intensity, physical impairment, and pain-related fear to disability in patients with chronic mechanical neck pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(12):1070–1076. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31827449a5

75. Bensing JM, Verheul W. The silent healer: the role of communication in placebo effects. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(3):293–299. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.033

76. Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG. Placebo effects in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):8–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1504023

77. Testa M, Rossettini G. Enhance placebo, avoid nocebo: how contextual factors affect physiotherapy outcomes. Man Ther. 2016;24:65–74. doi:10.1016/j.math.2016.04.006

78. Rossettini G, Carlino E, Testa M. Clinical relevance of contextual factors as triggers of placebo and nocebo effects in musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):27. doi:10.1186/s12891-018-1943-8

79. Zou K, Wong J, Abdullah N, et al. Examination of overall treatment effect and the proportion attributable to contextual effect in osteoarthritis: meta- analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(11):1964–1970. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208387

80. Samwel H, Oostendorp RAB. Iatrogene symbiose: valkuil of springplank voor patiënt en fysiotherapeut (Iatrogenic symbiosis: pitfall or springboard for patient and physiotherapist). Ned Tijdschr Fysiother. 2011;121(3):140–145. Dutch.

81. Hendriks EJ, Scholten-Peeters GG, van der Windt DA, et al. Prognostic factors for poor recovery in acute whiplash patients. Pain. 2005;114(3):408–416. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.006

82. Kasçh H, Qerama E, Kongsted A, Bendix T, Jensen TS, Bach FW. Clinical assessment of prognostic factors for long term pain and handicap after whiplash injury: a 1-year prospective study. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(11):1222–1230. doi:10.1111/ene.2008.15.issue-11

83. Sterling M, Juli G, Vicenzino B, Kenardy J, Darnell R. Physical and psychological factors predict outcome following whiplash injury. Pain. 2005;114(1–2):141–148. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.005

84. Ritchie C, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J, Sterling M. Derivation of a clinical prediction rule to identify both chronic moderate/severe disability and full recovery following whiplash injury. Pain. 2013;154(10):2198–2206. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.001

85. Wingbermühle RW, van Trijffel E, Nelissen PM, Koes B, Verhagen AP. Few promising multivariable prognostic modeIs exist for recovery of people with non-specific neck pain in musculoskeletal primary care: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2018;64(1):16–23. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2017.11.013

86. Daenen L, Nijs J, Raadsen B, Roussel N, Cras P, Dankaerts W. Cervical motor dysfunction and its predictive value for long-term recovery in patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(2):113–122. doi:10.2340/16501977-1091

87. Singla M, Jones M, Edwards I, Kumar S. Physiotherapists’ assessment of patients’ psychosocial status: are we standing on thin ice? A qualitative descriptive study. Man Ther. 2015;2015(20):328–334. doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.10.004

88. Synnott A, O’Keeffe M, Bunzli S, Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K. Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61:68–76. doi:10.1016/j.jphys.2015.02.016

89. Sleijser-Koehorst MLS, Bijker L, Cuijpers P, Scholten-Peeters GGM, Coppieters MW. Preferred self -administered questionnaires to assess fear of movement, coping, self -efficacy, and catastrophizing in patients with musculoskeletal pain. A modified Delphi study. Pain. 2019;160(3):600–606.

90. Nijs J, Leysen L, Vanlauwe J, et al. Treatment of central sensitization in patients with chronic pain: time for change? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;29:1–10.

91. Sterling M, de Zoete RMJ, Coppieters I, Farrell SF. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain part 4: neck pain. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):E1219. doi:10.3390/jcm8081219

92. Malfliet A, lckmans K, Huysmans E, et al. Best evidence rehabilitation for chronic pain. Part 3: low back pain. J Clin Med. 2019;8(7):E1063. doi:10.3390/jcm8071063

93. Meeus M, Nijs J, Hamers V, lckmans K, Oosterwijck JV. The efficacy of patient education in whiplash associated disorders: a systematic review. Pain Physician. 2012;15(5):351–361.

94. Chen K, Andersen T, Carroll L, et al. Recommendations for core outcome domain set for Whiplash-Associated Disorders (CATWAD). Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):727–736. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000735

95. Heerkens YF, Lakerveld-Heyl K, Verhoeven ALJ, Hendriks HJM. KNGF-richtlijn Fysiotherapeutische verslaglegging. Ned Tijdschr Fysiother. 2007;117(6):Supplement 1–20. Dutch.

96. Hoque DME, Kumari V, Hoque M, Ruseckaite R, Romero L, Evans SM. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0183667. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183667

97. Van Hassel DTP, Kenens RJ Cijfers uit de registratie van fysiotherapeuten. Peiling 1 Januari 2012. Availabie from: https://www.nivel.nl/nl/publicatie/cijfers-uit-de-registratie-van-fysiotherapeuten-de-eerste-lijn-peiling-1-januari-2012.

98. Scholten-Peeters GG, Neeleman-van der Steen CW, van der Windt DA, Hendriks EJ, Verhagen AP, Oostendorp RA. Education by general practitioners or education and exercises by physiotherapists for patients with whiplash-associated disorders? A randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(7):723–731.

99. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie. KNGF-Richtlijn Fysiotherapeutische Dossiervorming (KNGF-Guidelines Patient’s Documentation Physiotherapy). Amersfoort: KNGF; 2016. Dutch.

100. Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie. KNGF-Richtlijn Fysiotherapeutische Dossiervorming (KNGF-Guideline Patient’s Documentation Physiotherapy). Amersfoort: KNGF; 2019. Dutch.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.