Back to Journals » Journal of Healthcare Leadership » Volume 9

Leadership requirements for Lean versus servant leadership in health care: a systematic review of the literature

Authors Aij KH, Rapsaniotis S

Received 19 August 2016

Accepted for publication 5 December 2016

Published 18 January 2017 Volume 2017:9 Pages 1—14

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S120166

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Russell Taichman

Kjeld Harald Aij, Sofia Rapsaniotis

VU University Medical Center, Division Acute Care and Surgery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Abstract: As health care organizations face pressures to improve quality and efficiency while reducing costs, leaders are adopting management techniques and tools used in manufacturing and other industries, especially Lean. Successful Lean leaders appear to use a coaching leadership style that shares underlying principles with servant leadership. There is little information about specific similarities and differences between Lean and servant leaderships. We systematically reviewed the literature on Lean leadership, servant leadership, and health care and performed a comparative analysis of attributes using Russell and Stone’s leadership framework. We found significant overlap between the two leadership styles, although there were notable differences in origins, philosophy, characteristics and behaviors, and tools. We conclude that both Lean and servant leaderships are promising models that can contribute to the delivery of patient-centered, high-value care. Servant leadership may provide the means to engage and develop employees to become successful Lean leaders in health care organizations.

Keywords: management, leadership attributes, efficiency, patient-centered, high-value care

Introduction

Faced with uneven quality, lapses in patient safety, pressure to curtail costs, rapidly aging populations, and rising technology expenses, health care organizations are seeking ways to improve quality and efficiency while reducing costs.1,2 Health care leaders are adopting management techniques and tools used in manufacturing and other industries, especially Lean, a management philosophy that focuses on improving processes and eliminating waste to add value for customers. Lean calls for a holistic change in management style and organizational culture, requiring leaders to develop new skills and attitudes and adopt new behaviors.

Effective Lean implementation requires leadership at all levels of the organization to systematically align Lean philosophy and tools with the organization’s strategic goals, vision, and values. Health care organizations that have implemented Lean comprehensively and systematically have seen improvements in quality, patient safety, and employee satisfaction.1,3,4 Yet few health care organizations have achieved sustainable, long-term implementation of Lean. All too often, health care and other organizations attempt to implement Lean via piecemeal application of methods and tools, rather than creating holistic cultural change that promotes involvement of employees in daily improvement and behavioral changes.5–7

The centrality of leadership to Lean initiatives has been widely acknowledged.7–10 For instance, Mann7 observed that 80% of Lean implementation depends on senior management’s creation of an environment that fosters success. Several authors have described the specific leadership characteristics and behaviors that are associated with successful and sustainable Lean transitions in health care.7 Characteristics of successful Lean leaders that have been described include empowerment, trust, modesty, openness, and respect for people.3,7,11

Existing findings suggest that successful Lean leaders use a coaching leadership style6,7 that shares underlying principles with servant leadership. However, despite the apparent synchronicity of the two approaches, specific similarities and differences between Lean and servant leaderships have not been described. We address that gap by performing a comparative analysis of Lean and servant leaderships in health care. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically examine and organize the current body of research literature that either quantitatively or qualitatively explores servant leadership and Lean leadership in health care organizations.

Background

Leadership

Leadership has been defined as “a process by which one person sets the purpose or direction for one or more persons and helps them to proceed competently and with full commitment”.11 A broad body of work on leadership suggests that there are many appropriate ways to lead and that there are many styles of leadership.12 Some studies examine leadership as a process;13 however, most theories and studies describe traits, qualities, and behaviors of the person who is considered the leader.12 A broader view of leaders as cultural change agents has emerged since the 1980s.14 According to this view, effective leaders clearly identify and address issues related to organizational culture, adapting to change as the environment shifts and develops. Researchers have also identified the following two types of leadership: “transactional” in which leaders motivate employees through consequences and rewards and “transformational” in which leaders motivate followers by satisfying higher order needs and more fully engaging them in the process of the work.12,15,16 Both Lean and servant leaderships are understood as types of transformational leadership.

Lean leadership

Lean thinking is based on creating maximum value for the client by minimizing waste and assuring value that is added at every step of all processes.11 Goodridge et al17 described the following five key principles of Lean: 1) identify customers and specify value, 2) identify and map the value stream, 3) create flow by eliminating waste, 4) respond to customer pull, and 5) pursue perfection. Employee participation and knowledge are considered central to the Lean organization.5 Lean leaders are coaches who create the strategy, build the team, and help employees develop their skills. Dombrowski and Mielke5 described the following five basic principles of Lean leadership:

- Improvement culture: strive for perfection but view failure as an opportunity for improvement.

- Self-development: act as role models for others in the organization.

- Qualification: commit to long-term development of employees and continuous learning.

- “Gemba”: commit to managing from the shop floor and making decisions based on firsthand knowledge.

- “Hoshin kanri”: work to align goals on all levels, always retaining focus on the customer.

Servant leadership

Greenleaf’s theory of servant leadership is based on the idea that leaders should serve their followers.18–20 In contrast to leadership theories that focus on the leader’s actions, servant leadership defines leaders by their character and their commitment to serving others.21 Servant leaders seek to develop a sustainable organization, bring out the best in employees, and serve the community.21 Laub22 investigated servant leadership in organizations, defining it as a philosophy in which “the good of those led over the self-interest of the leader”. He identified the following six key areas of an effective servant-minded organization:

- Values people: believing, serving, and nonjudgmentally listening to others;

- Develops people: providing learning, growth, encouragement and affirmation;

- Builds community: developing strong collaborative and personal relationships;

- Displays authenticity: being open, accountable, and willing to learn from others;

- Provides leadership: foreseeing the future, taking initiative, and establishing goals; and

- Shares leadership: facilitating and sharing power.

Research framework: servant leadership model

In their practical model of servant leadership, Russell and Stone23 identified functional and accompanying attributes of servant leadership (Figure 1). They defined functional attributes of servant leadership, such as vision, honesty, integrity, trust, service, modeling, pioneering, appreciation of others, and empowerment. The model shows the relationship between the leader’s attributes and the manifestation of servant leadership. Servant leadership is considered as a controllable independent variable that affects the dependent variable of organizational performance. However, several mediating variables, such as organizational culture, social context, and the broader culture, may influence the effectiveness of both Lean and servant leaderships and affect the organizational performance. The model includes all important aspects of leadership in an organization and demonstrates its complexity. We substituted Lean leadership in Russell and Stone’s model and then compared servant leadership with Lean leadership.

| Figure 1 Servant leadership attributes model. Note: Reprinted with permission from Emerald Group Publishing Limited, originally published in Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol 23, Issue 3, © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 2002.23 |

Methods

We conducted a systematic narrative review24 of published articles about Lean leadership and servant leadership to identify different aspects of servant and Lean leaderships in health care. We systematically searched relevant terms using the Web of Science, Embase, and Emerald databases. Search syntax was based on the variables described in the Lean leadership model25 and servant leadership model.20,26 Initial inclusion criteria were English-language articles describing an empirical study or comprising a theoretical secondary review published in peer-reviewed journals. No restriction was placed on the year of publication. For the initial search, the search syntaxes were as follows: 1) “Lean leadership”, 2) “servant leadership”, and 3) “health care”. Table 1 provides an overview of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria |

These elements were translated into the search terms “origin”, “philosophy”, “characteristics”, “values”, “tools”, “organizational culture”, and “organizational outcomes” and combined for both Lean leadership and servant leadership into the following search syntaxes: (“Lean leadership” [all fields] OR “servant leadership” [all fields]) AND (“origin” [all fields] OR “philosophy” [all fields] OR “characteristics”[all fields] OR “attributes” [all fields] OR “values” [all fields] OR “tools” [all fields] OR “organizational culture” [all fields] OR “organizational outcomes” [all fields]) AND (“health care” [all fields] OR “healthcare” [all fields] OR “hospital” [all fields]).

Of the >10,000 citations, 983 potentially relevant references were identified during the first screening. Articles were exported to Covidence, a web-based software platform, and screened for duplicates and presence of keywords in the title and/or abstract. Three duplicates were excluded as a result. Two articles were excluded because full text was not available online. After identifying all possible studies, we conducted a second screening to assess eligibility against inclusion criteria, and full-text articles were retrieved for articles that met the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for the second screening were that, in addition to being in the English language, published, and peer reviewed, the article must 1) have as its main topic Lean leadership or servant leadership; 2) describe Lean or servant leadership in the context of health care; 3) describe one or more aspects of leadership (origin, philosophy, values, characteristics, tools, organizational culture, and organizational outcome); 4) be based on empirical or systematic research.

Further examination revealed that 193 articles were based on empirical research or systematic research. Three articles were added through backward and forward citations, resulting in 196 articles identified in the initial search: 33 articles through Web of Science, 87 articles through Emerald, 73 articles through Embase, and three articles through a snowball approach. Of these 196 articles, 167 articles did not adequately relate to the topic, leaving 29 articles. Figure 2 shows the procedure of article selection.

| Figure 2 Article selection procedure. |

Articles were coded based on the following aspects of the leadership model developed by Stone et al:20 “tools”, “organizational culture”, “organizational performance”, “values”, and “characteristics” as relevant variables for (servant) leadership. These variables, as well as the variables’ origin and philosophy, were used as starting point of the coding process. Variables were specified for both Lean leadership and servant leadership in health care.

Results

In total, 29 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Table 2). Of the articles reviewed, 11 articles were case studies and 18 articles were theoretical, including systematic reviews. The majority of articles (17) were on the topic “Lean”, and 12 articles addresssed servant leadership. Table 3 presents a summary comparison of the two leadership styles by variable. The full synthesis of study results is included in the Supplementary materials.

| Table 2 References reviewed by leadership style |

| Table 3 Comparison of Lean leadership and servant leadership Abbreviation: PDCA, plan do check act. |

This comparison of Lean and servant leaderships shows a significant overlap between the two models, especially in the “softer” aspects of leadership, such as organizational culture, empowerment and respect for people, and person-oriented leadership. Lean leaders start with building an environment in which people can succeed, while servant leaders begin by supporting people to build a successful organization. Shared goals include employee and patient satisfaction and building a sustainable learning organization. Key similarities and differences identified in this study, organized by dependent variable, are as follows:

- Origins: Lean and servant leadership styles contrast sharply in their origins. Lean was developed in the 1950s and grew out of previous work in the production management; its origins have been traced to automaker Henry Ford. Servant leadership was first articulated as a theory by Greenleaf in 1970 but has its basis in theological and philosophical traditions dating back to ancient times.

- Philosophies: in contrast with Lean leadership, in which the ultimate goal is the well-being of the organization, servant leadership “is genuinely concerned with serving followers”.27 Lean philosophy emphasizes waste reduction and process perfection, while servant leadership uses a “serve the people first” philosophy. However, both servant leadership and Lean leadership work toward a sustainable organization. Respect for people and employee empowerment are central to both Lean and servant philosophies.

- Characteristics and behaviors: many servant leadership characteristics and behaviors have been described, while the characteristics and behaviors of Lean leaders were the focus of fewer articles. Both leadership styles focused on self-development and development of people, empowerment of others, building trust, listening, and modeling behaviors. A coaching leadership style is used in both models. Notable differences included the Lean focus on removing barriers versus servant leaders’ primary interest in “building” people. While the Lean leader bases his or her actions on scientific methods and uses highly structured tools to perfect organizational processes, servant leadership is based on an explicit spiritual, moral, and ethical stance.

- Values: both leadership styles rest on the premise that leaders’ values and beliefs shape their decisions and actions. In addition, both Lean and servant leaderships strive to empower employees by developing them. While Lean values are based on processes in an organization, servant leadership values are derived from a focus on people. For example, standardization is seen in a Lean organization as a means of continuous improvement and employee empowerment. In contrast, in a servant organization, leaders are asked not to use checklists but to treat each employee as an individual.

- Tools: tools – specific methods and materials used to achieve leadership goals – were described in both Lean and servant leadership articles. Lean leaders must learn and use many tools, most of which focus on process improvement, with the ultimate goal of effective and efficient production. Studies of servant leadership reframe leadership behaviors as tools. The servant leader’s tools are his or her characteristics and commitment to serve and inspire followers. Many of these characteristics involve interpersonal interaction and contribute to strong relationships and trust between leaders and others.2,27,28

- Organizational culture: both Lean and servant leaders must adapt to existing culture in the organization and ultimately change the culture to match the philosophy, values, and tools of the chosen leadership style. Lean leaders work to create an improvement culture, in which employees are engaged and empowered to identify problems and propose and enact changes. In contrast, servant leaders develop a people-oriented culture that is based on trust, concern for others, learning, and an attitude of service. Transparency, justice, and safe environments are essential to both Lean and servant cultures.

- Organizational performance: long-term sustainability of the organization is a core concern for both Lean and servant leaders. However, Lean leaders focus on developing competitive advantage through streamlined, waste-free work processes, while servant leaders focus on developing collaborative teams. Fewer tangible outputs were identified for servant organizations than for Lean organizations, but both align with current efforts to deliver patient-centered, high-quality, cost-effective care. Shared intangible outputs were increased patient safety, increased employee empowerment, and increased patient satisfaction.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic literature review was to provide insight into the similarities and differences between Lean and servant leaderships. Using the servant leadership model developed by Russell and Stone,20 we found significant overlap between Lean and servant leadership values, characteristics and behaviors, and goals for organizational culture and organizational performance but notable differences in origins, philosophy, and tools.

Origins

Lean thinking builds on a long and notable history of structured process improvement methodologies.17 While Greenleaf26 was the first to theorize servant leadership, the model arises from long-held religious and philosophical belief systems.28–31

Origins of Lean leadership

All 17 articles in this review pertaining to Lean cited the Toyota Production System (TPS) as the basis for Lean, generally crediting engineer Taiichi Ohno with developing Lean processes in the 1950s. All articles noted the term Lean was introduced in the 1980s by Womack and Jones.3,7,11,32,33 Womack and Jones25 were also the first to propose that Lean thinking could be applied to health care.

Three research teams pointed out that Lean thinking is heavily influenced by the work of early industrialists and quality improvement experts such as Henry Ford and Walter Edwards Deming, and the scientific method that forms the basis of most quality management systems.3,8,17 Clark et al4 observed that many elements of TPS and Lean can be found in the Training Within Industry (TWI) program, which was developed by US Department of War in 1940 to provide consulting services in industries involved in the war effort. The TWI program was introduced to the Japanese industry as a part of the postwar reconstruction in the late 1940s. Similarly, Al-Balushi et al8 located the origins of Lean in post-World War II Japan.

Origins of servant leadership

The 12 articles in this review that addressed servant leadership credited Greenleaf (1904–1990) with theorizing the concept in its modern form. Greenleaf’s three seminal essays, “The Servant as Leader” (1970), “The Institution as Servant” (1972), and “Trustees as Servant” (1972), were the first publications to describe servant leadership as an organizational strategy.28 Parris and Peachey28 observed that many principles articulated by religious and historical leaders are mirrored in servant leadership theory. Servant leadership was associated with Christianity in three articles.28–30 Service is also a central concept in Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, as well as in many nonreligious philosophies.28

Philosophy

Fundamental differences were identified in the philosophy and background of Lean versus servant leadership. Lean leaders focus on the process first, adopting a philosophy of “zero waste”, and, through respect, training, and listening, empower people to achieve better processes. In contrast, the philosophical focus of servant leadership is on others rather than upon self; the servant leader’s fundamental motivation is a desire to serve.

Lean philosophy

All 17 Lean articles in this review defined Lean as a philosophy of management that informs programs and projects, quality initiatives, and leadership styles. The majority of Lean articles in this review cited the following two core elements as the basis of Lean philosophy: 1) a systematic approach to improve processes and maximize value by removing waste and 2) a commitment to respect.1,3,11,17,32,34,35 In the Lean framework, activities are streamlined and activities are standardized, always focusing on adding value for the customer.8,17,24

These principles drive the Lean organization and shape the work of Lean leaders. Lean leaders must have or have or acquire certain skills, attitudes, and knowledge, including the ability to model Lean principles and use Lean tools.7,36,37 Strategically, Lean leaders focus on key leadership principles, which play out operationally in the form of tools and techniques.1,11,17 Dombrowski and Mielke5 defined the following five basic principles of Lean leadership across sectors:

- Improvement culture: leaders continuously strive for perfection and ask the same of employees and associates. Failures are seen as possibilities for improvement.

- Self development: Lean leaders must learn the philosophy, values, tools, and techniques of Lean. They serve as role models for others and live out core Lean principles while encouraging others to develop their skills and knowledge.

- Qualification: the Lean leader creates an environment of continuous improvement, in which employees are constantly learning, assessing themselves and processes, and solving problems. Qualification occurs partly through training and education but mostly during daily activities on the shop floor. Lean leaders use coaching approaches to help employees perform their best.

- Gemba: the Lean leader regularly “goes to the gemba”, a Japanese word meaning “the real place”. The gemba is the place where value is added, sometimes referred to as the “place of work” or the “shop floor”. The Lean leader goes to the gemba to coach and learn from employees.

- Hoshin kanri: it is a strategic planning method used to ensure that improvement activities are in alignment with long-term goals.

Servant leadership philosophy

All 12 articles on servant leadership in this review cited Greenleaf’s definition, either directly or indirectly, as the underlying philosophy of the model: “It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead.”26 Greenleaf emphasizes that servant leaders approach their tasks as a calling – a “natural feeling” that one is called to serve that leads to the “conscious choice” of taking on the leadership role. Servant leaders deliberately put others’ needs, goals, and hopes above their own, with the goal of helping others become more productive and effective.18,22,28,30,38 All reviews and summaries retained Greenleaf’s premise that the role of the servant leader is to develop people, helping them to strive and flourish.2,20,23,28,30,39

Servant leaders strive to develop a sustainable organization, bring out the best among employees, serve the community (including patients), and act as stewards of the environment.23,26,28 Through serving others, servant leaders create an organization that empowers followers – specifically, in Greenleaf’s26 framework, to “become healthier, wiser, freer, and more autonomous”. Several authors attempted to explicate this concept. Trastek et al2 noted Greenleaf’s underlying assumption that if followers are treated as ends in themselves, rather than means to an end, they will perform at their best. Stone et al20 suggested that servant leaders respect, value, and motivate those who follow them.

Characteristics

Both Lean and servant leaders focus on enabling employees to work more effectively, to be successful, and to feel responsible for their work. However, servant leaders approach their work with an explicit spiritual, moral, and ethical base.30

Characteristics of Lean leaders

The 17 Lean articles reviewed all noted that successful Lean implementation requires organization-wide changes in behavior, culture, and attitude and that these changes require strong leadership. Mann7 observed that Lean leadership seems to be the “missing link” between Lean production and maintaining a sustainable continuous improvement process. All Lean articles also emphasized the problem-solving focus of Lean, which requires leaders to find solutions to problems rather than assign blame and to create an environment in which problems are recognized as opportunities for improvement. Qualification of employees and establishment of a continuous learning environment were identified as fundamental tasks.17,24

All Lean articles in this review described the gemba principle of Lean leadership. “Going to the gemba” is both a tool and a behavior of Lean leaders. Skilled Lean leaders regularly perform gemba walks, which allow them to see and assess processes and whether they align with the organizational purpose and vision. For instance, a gemba walk might reveal several workarounds to a process, indicating that the process needs to be remapped and revised. Properly conducted, gemba walks foster trust and respect between senior management and staff.

Only four articles specifically addressed behaviors and characteristics of Lean leaders.11,17,32,37 Self-development is critical for Lean leaders, as Lean leadership requires new leadership skills and act as coaches, helping others develop new skills and knowledge. Aij et al11 found that successful Lean leaders go to the gemba, empower employees, and act with modesty. Lean leaders in their study helped employees develop trust and a sense of ownership in their work by performing gemba walks, being open and responsive to employees’ perspectives, and empowering employees to solve problems, always showing that respect through modesty is a crucial element of respect.11 Other authors have described the following additional characteristics of Lean leaders: motivating others, establishing goals, removing barriers, delegating duties, involving in management activities, and respecting the people who do the work.17,32,37

Characteristics and behaviors of servant leaders

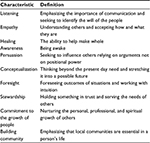

All articles about servant leadership focused on the characteristics and behaviors of leaders. Following Greenleaf, these 12 articles emphasized that servant leadership is a “calling” and that the servant leader puts others first. Spears19 derived the following 10 characteristics and behaviors from Greenleaf’s work: listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, philosophy, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth of people, and building community (Table 4). Russell and Stone23 identified other characteristics that are consistent with Greenleaf’s writings and grouped them into nine functional attributes and 11 accompanying attributes. They defined functional characteristics as “the operative qualities, characteristics, and distinctive features belonging to leaders and observed through specific leader behaviors in the workplace”.23 Accompanying attributes appear to supplement the functional characteristics. Functional and accompanying attributes are summarized in Table 5.

| Table 4 Ten characteristics and behaviors of servant leaders Note: Adapted with permission from Emerald Group Publishing Limited, originally published in Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol 17, Issue 7, © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 1996.19 |

| Table 5 Functional and accompanying characteristics of servant leadership Note: Adapted with permission from Emerald Group Publishing Limited, originally published in Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol 23, Issue 3, © Emerald Group Publishing Limited 2002.23 |

In his review, van Dierendonck27 identified 44 overlapping characteristics in different models. By combining conceptual models with empirical evidence, he identified the following six key characteristics of the servant leader: 1) empower and develop people, 2) show humility, 3) act authentically, 4) accept people for who they are, 5) provide direction, and 6) act as a steward who works for the good of the whole.

Values

Lean and servant models shared the core value of respect for others. Servant leaders pair respect with humility, a value that could be usefully incorporated into Lean models.

Values of Lean leadership

All 17 Lean articles reviewed described core values of Lean leadership, most echoing Simon et al’s40 summary of those values, as follows: 1) respect for people, 2) continuous improvement, and 3) human development.

Lean leaders extend respect to employees, partners, and suppliers when they challenge those associates and help them improve, leading to increased employee empowerment and satisfaction. In health care settings, Lean leaders show respect for patients and their families when they listen to and act upon their input.3 All 17 Lean articles cited continuous improvement as a core Lean value. Continuous improvement leads to decreased cost, decreased waste, and an increase in the value of the organization.4,33 Working smarter and doing more with less were values cited in the majority of articles. Five articles noted that continuous improvement is fostered by “kaizen” events, quality improvement events that focus on improving specific processes through small, incremental changes.1,4,36,41,42 Continuous improvement projects focus on patient and employee safety, quality, effectiveness, and efficiency, including optimal clinical care and administrative tasks.1,33 Human development is the third core value of Lean leaders, who must develop exceptional people and teams.37

Servant leadership values

The servant leadership model is based on the values of humility and respect for others.43 Servant leaders seek to bring out the best in employees, serve the community, and act as stewards of the environment.21,43 Employee empowerment and growth are valued. Servant leaders build followers’ leadership potential and grow their followers into more capable members of the organization.23,2,32 Seven articles cited individualized attention, rather than dependence on standardized checklists, as a core value.2,20,28,29,30,32,44

Servant leaders assert the importance of values, beliefs, and principles in leadership. The majority of authors23,2,21,32,43 cited values themselves as core elements of servant leadership.

Tools

In contrast to the structured tools of Lean leadership, the tools used by servant leaders are intrinsically linked to the attitudes, behaviors, and characteristics inherent in the model.29,43 Adaptation of Lean tools by servant leaders has the potential to reduce variability and improve efficiency and safety.

Tools in Lean leadership

Lean leaders are expected to be well versed in the use of Lean tools and training others to use them.3,7,17,41 Lean leaders must build cross-functional teams that use tools to improve practices and processes. The Lean tools most commonly referred to in the surveyed articles were as follows: kaizen events, A3 framework including plan do check act (PDCA) cycles, standardized work instructions, just-in-time, 5S visual workplace (sort, set in order, shine, standardize, and sustain), 5-whys (a problem solving tool) and kanban (a card visual system for feedback within the system), gemba walks, and “jidoka” (stopping production immediately in case of an error).1,7,11,17,36,41,42

All Lean tools are designed in alignment with the core Lean philosophy of reducing waste and increasing productivity by focusing on processes. A kaizen event, also called a rapid improvement event (RIE), is a fundamental Lean tool and is often used to begin a Lean initiative.1,9,36,41 The A3 framework provides structure to the problem-solving process from identification to solution.4,42 The PDCA cycle, developed by Walter Edwards Deming, is a scientific process for implementing and monitoring change.1,5,7,42

Other typical Lean tools include “just in time” – producing only what is needed by the next process in a continuous flow18,41 – and “kanban” – or “visual card”, which is used to signal problems in processes.17,41 Jidoka is the ability to stop production lines when problems occur (for instance, poor quality and malfunctioning equipment).17,34 The 5S visual workplace tool, described by Goodridge et al17 and others, is a method to organize and maintain a clean workplace. To reveal the root cause of a problem, leaders use the “5-whys”, ie, asking “why?” at least five times.4,41 Hoshin kanri, which translates from the Japanese as “compass control”, is the strategic planning tool used by Lean leaders.34 Regular gemba walks are used to assess, measure, and sustain changes. As previously discussed, going to the gemba is a key leadership behavior; it is also a tool that skillful Lean leaders wield well. Leaders can use gemba visits to create rapport with employees, assess the impact of changes, and address problems. The “five golden gemba rules”, as described by Dombrowski and Mielke5, apply across the following sectors: 1) when a problem arises, go to the gemba; 2) analyze all things that might be involved in the problem; 3) create a temporary solution; 4) use the 5-whys method to find the root cause of the problem; and 5) standardize.

Tools in servant leadership

Servant leadership “operates not only on a surface level but deep within a person’s being”.29 In other words, the servant leader’s tools are his or her characteristics and commitment to serve and inspire followers to achieve their own goals and meet the organization’s objectives.2 Servant leadership is characterized as “a way of being”39 that is intrinsically motivated by values and beliefs.29,30 The personal values of the people who adopt the model can determine the success or failure of initiatives.43 The leader, by modeling service, also encourages followers to serve.20 By expressing humility, authenticity, and stewardship and providing direction through vision, the servant leader empowers and develops people.28

Organizational culture

Organizational culture, which Mann7 defines as “the way we do things here”, is a critical component of organizational sustainability. Both Lean and servant models focus on building a safe, transparent environment; the servant leader’s emphasis on humility and service can inform the Lean leader’s efforts to create a positive culture in which employees are willing and empowered to change for the better.1

Organizational culture and Lean leadership

All Lean articles in this review posit that organizational culture is a direct result of management systems and leadership style. Lean implementation requires changes in leadership behavior and practices that, with long-term commitment from Lean leaders, changes organizational culture.3,7 Improvement culture is paramount in Lean organizations.3,4,7,17,36,38 Lean leaders must constantly challenge current processes to improve them and engage all employees – not just senior managers – in identifying and solving problems.4,17,38 In turn, widespread employee involvement helps bring about the cultural change necessary for true Lean transformation.4

The Lean leader must ensure that employees clearly understand the links between Lean project activities and objectives, organizational objectives, and organizational goals. Transparency is frequently cited as an important aspect of Lean culture and is seen as necessary to create an environment in which mistakes are seen as opportunities for learning, not for blaming and disciplining employees.1,17,42,45 Lean leaders improve systems by developing a “just and nonpunitive culture that avoids casting blame”.42 In this way, a learning culture is created in which people respect others.

Organizational culture and servant leadership

Servant leaders seek to develop a culture that is based on trust, justice, concern for others, a safe psychological environment, transparency, learning, and an attitude of service.21,28,29,43 In servant culture, a servant leader is seen as a steward who gains followers’ trust.21,28 Trust is fostered partly through justice, which, in turn, creates an open and trusting environment and enhances collaboration among employees.29 By fostering collaboration, the servant leader creates a “helping culture”,29 thus increasing prosocial and altruistic behaviors of employees.29 Similarly, van Dierendonck28 describes servant culture as a safe psychological environment in which “a servant leader provides direction by emphasizing the goals of the organization, its role in society, and the separate roles of the employees” and cites feelings of trust and fairness as essential elements of servant culture.

Like Lean culture, servant leadership culture requires transparency and employees must be clearly informed about the organization’s strategy.28 Failures and shortcomings can be reviewed and addressed in a safe environment, resulting in a learning environment in which employees are empowered.28,30,43 In a servant leadership culture, employees feel safe using their knowledge and are able to focus on continuous development and learning.28 Through service and humility, health care servant leaders build a community in which employees are committed to putting the patient’s interest first and organizing team members to provide high-value patient care.2

Organizational performance

Positive tangible outcomes were frequently reported in studies of Lean leadership, while positive intangible outcomes were more frequently reported in studies of servant leadership.

Organizational performance and Lean leadership

Six of the 17 Lean studies reviews focused on organizational outcomes after Lean implementation.1,3,8,9,33,37 In addition, Mann7 focused on how Lean leadership plays out at three organizational levels. Reported results included both tangible and intangible outputs.9 The most frequently noted tangible outputs were reduced error rates, shorter waiting times, and increased productivity.1,8,9,33 Decreases in waiting time and errors led to reduced costs; fewer errors resulted in reduced morbidity and mortality and thus improved patient safety.1 Intangible outputs included increased employee motivation and satisfaction and increased patient satisfaction.9 Abuhejleh et al1 found that Lean markedly and sustainably increased patient access, improved safety and patient satisfaction, and increased employee empowerment.

In a study of Lean implementation in four emergency departments, Dickson et al41 found that successful Lean implementation depended on both leaders’ and followers’ degree of adherence to Lean principles and willingness change the culture. They described the following three key factors for successful Lean implementation: 1) engaged frontline workers who come to “own” Lean, 2) long-term leadership commitment, and 3) a flexible workforce that is open to change. Similarly, Abuhejleh et al1 found that “champions”, including leadership, management, and employees, were important to the success of Lean implementation.

Organizational performance and servant leadership

Articles reviewed suggest that servant leadership can bring real and fundamental change to health care organizations.20,21,29,44 Servant leadership appears to increase employee satisfaction, commitment, and well-being and positively influence organizational performance.2,20,29 Trastek et al2 observed that servant leadership can improve organizational sustainability by aligning health care providers to serve patients and each other.

Intangible outcomes of servant leadership included enabling employees to work more effectively, feel responsible for their work, develop trust in the organization, and be empowered.29 Several authors2,28,29,44 found support for Greenleaf’s26 claim that employees in a servant organization become “healthier, wiser, freer and more autonomous”. The servant leader’s person-oriented attitude creates strong relationships – and employees who are more satisfied and committed and perform better.28,29 Two reviews reported gains in personal growth of employees and better collaboration between team members and increased team effectiveness.28,29

However, tangible outcomes were more rarely defined in the servant leadership literature. The few studies that addressed tangible outcomes of servant leadership found associations with improved quality of care, reduced costs, and procedural justice.2,30 The servant leadership characteristics of listening, empathy, awareness, healing, and persuasion appear to contribute to healthy relationships between administrators and clinical staff, as well as between providers and patients. These interpersonal skills also form the core of patient-centered communication, which has been linked to increased patient satisfaction and adherence and better health outcomes. In their review, Parris and Peachey29 analyzed 16 empirical studies on servant leadership and found that servant leadership in an organization increases trust in both the leader and the organization and enhances the justice of processes in the hospital.

Implications

Our findings suggest that strategic use of servant leadership may strengthen Lean implementation in the health care setting. Successful Lean implementation depends on wholesale change in organizational culture. It may be possible to use the overlapping servant leadership variables identified here to support the cultural and philosophical changes that form the basis of Lean and avoid the tool-oriented approaches that have led to failed Lean initiatives.

This comparison of Lean and servant leaderships offers opportunities for further study and application. Our results suggest, however, that Lean and servant leaderships could be combined to help achieve patient-centered, high-quality, cost-effective care, address provider burnout, and contribute to sustainability of health care organizations.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The majority of servant leadership articles in this review were based on anecdotal or philosophical studies, not empirical evidence. While studies of Lean were generally more rigorous, they, too, were of uneven quality. The paucity of work on the characteristics and behaviors of Lean leaders calls for more work to be done in this area. Additional data linking statistical analyses, including ranking of behaviors and impacts, could alter our results. In addition, articles selected for review analyzed by one person increases the risk of inclusion bias.

Much further work needs to be done, including empirical research into the characteristics and behaviors of successful Lean leaders and the specific actions of servant leaders. In addition, more research is needed to specify ways in which the two models can blend in various health care settings such as hospitals, clinics, and public health systems.

Conclusion

Both Lean leadership and servant leadership are promising models that can contribute to the delivery of patient-centered, high-value care. This outline of their similarities and differences can provide a roadmap for leaders to inspire high performance and innovation in health care. Understanding key aspects of servant leadership may inform the development of Lean leaders and contribute to the success of Lean transitions; conversely, servant leaders may benefit from understanding ways that Lean may contribute to measurable quality metrics and effective processes. Successful Lean transitions require systematic and systemic change that engages people at all levels of the organization. Servant leadership may provide the means to engage and develop employees to become successful Lean leaders in health care organizations.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Abuhejleh A, Dulaimi M, Ellahham S. Using lean management to leverage innovation in healthcare projects : case study of a public hospital in the UAE. BMJ Innov. 2016;2(1):22–32. | ||

Trastek VF, Hamilton NW, Niles EE. Leadership models in health care: a case for servant leadership. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(3):374–381. | ||

Clark DM, Silvester K, Knowles S. Lean management systems: creating a culture of continuous quality improvement. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66(8):638–643. | ||

Merlino JP, Petit J, Weisser L, Bowen J. Leading with lean: getting the outcomes we need with the funding we have. Psychiatr Q. 2015;86(3):301–310. | ||

Dombrowski U, Mielke T. Lean leadership – fundamental principles and their application. Proc CIRP. 2013;7:569–574. | ||

Emiliani ML, Stec DJ. Leaders lost in transformation. Leader Organ Dev J. 2005;26(5/6):370–387. | ||

Mann D. The missing link: lean leadership. Front Health Serv Manage. 2009;26(1):15–26. | ||

Al-Balushi S, Sohal AS, Singh PJ, Al Hajri A, Al Farsi YM, Al Abri R. Readiness factors for lean implementation in healthcare settings – a literature review. J Health Organ Manag. 2014;28(2):135–153. | ||

Papadopoulos T, Radnor Z, Merali Y. The role of actor associations in understanding the implementation of lean thinking in healthcare. Int J Oper Prod Manag. 2011;31(2):167–191. | ||

Ben-Tovim DI, Bassham J, Bolch D, Martin MA, Dougherty M, Szwarcbord M. Lean thinking across a hospital: redesigning care at the Flinders Medical Centre. Aust Health Rev. 2007;31(1):10–15. | ||

Aij KH, Visse M, Widdershoven GAM. Lean leadership: an ethnographic study. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl). 2015;28(2):119–134. | ||

Horner M. Leadership theory: past, present, and future. Team Perform Manag An Int J. 1997;3(4):270–287. | ||

Barker RA. The nature of leadership. Hum Relat. 2001;54(4):469–494. | ||

Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 2010. | ||

Burns JM. Leadership. New York: Harper & Row; 1978. | ||

Bass BM. From transactional to transformational leadership: learning to share the vision. Organ Dyn. 1990;18(3):19–31. | ||

Goodridge D, Westhorp G, Rotter T, Dobson R, Bath B. Lean and leadership practices: development of an initial realist program theory. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):362. | ||

Barbuto JE. Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group Organ Manag. 2006;31(3):300–326. | ||

Spears L. Reflections on Robert K. Greenleaf and servant leadership. Leader Organ Dev J. 1996;17(7):33–35. | ||

Stone AG, Russell RF, Patterson K. Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus. Leader Organ Dev J. 2004;25(4):349–361. | ||

Hanse JJ, Harlin U, Jarebrant C, Ulin K, Winkel J. The impact of servant leadership dimensions on leader-member exchange among health care professionals. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(2):228–234. | ||

Laub JA. Assessing the Servant Organization [Doctoral dissertation] Florida: Atlantic University; 1999:131. | ||

Russell RF, Stone GA. A review of servant leadership attributes: developing a practical model. Leader Organ Dev J. 2002;23(3):145–157. | ||

Hart C. Doing a Literature Review. London: Sage; 1998. | ||

Womack JP, Jones DT. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth for Your Corporation. 2nd ed. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2003. | ||

Greenleaf RK. The Servant as Leader. Atlanta, GA: Robert K Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership; 1970. Available from: https://www.greenleaf.org/products-page/the-servant-as-leader/. Acccessed May 20, 2016. | ||

van Dierendonck D. Servant leadership: a review and synthesis. J Manag. 2011;37(4):1228–1261. | ||

Parris DL, Peachey JW. A systematic literature review of servant leadership theory in organizational contexts. J Bus Ethics. 2013;113(3):377–393. | ||

Robinson FP. Servant teaching: the power and promise for nursing education. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2009;6(1):Article5. | ||

Sendjaya S, Sarros JC, Santora JC. Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviour in organizations: servant leadership behaviour in organizations. J Manag Stud. 2008;45(2):402–424. | ||

Waterman H. Principles of “servant leadership” and how they can enhance practice. Nurs Manag (Harrow). 2011;17(9):24–26. | ||

Dannapfel P, Poksinska B, Thomas K. Dissemination strategy for lean thinking in health care. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2014;27(5):391–404. | ||

Simon RW, Canacari EG. A practical guide to applying lean tools and management principles to health care improvement projects. AORN J. 2012;95(1):85–103. | ||

Dahlgaard JJ, Pettersen J, Park SM. Quality and lean health care: a system for assessing and improving the health of healthcare organisations. Total Qual Manag Bus Excel. 2011;22(6):673–689. | ||

Fine B, Golden B, Hannam R, Morra DJ. Leading lean: a Canadian healthcare leader’s guide. Healthc Q. 2009;12(3):26–35. | ||

Ljungblom, M. (2014). Ethics and Lean Management – a paradox? Int J Qual Serv Sci. 2014:6(2/3):191–202. | ||

Toussaint JS, Berry LL. The promise of lean in health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(1):74–82. | ||

Greenleaf RK. Servant-Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press; 2002. | ||

Huckabee MJ, Wheeler DW. Physician assistants as servant leaders: meeting the needs of the underserved. J Physician Assist Educ. 2011;22(4):6–14. | ||

Simon RW, Canacari EG. A practical guide to applying lean tools and management principles to health care improvement projects. AORN J. 2012;95(1):85-103. | ||

Dickson EW, Anguelov Z, Vetterick D, Eller A, Singh S. Use of lean in the emergency department: a case series of 4 hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(4):504–510. | ||

Johnson PM, Patterson CJ, O Connell MP. Lean methodology: an evidence-based practice approach for healthcare improvement. Nurse Pract. 2013;38(12):1–7. | ||

Russell RF. The role of values in servant leadership. Leader Organ Dev J. 2001;22(2):76–85. | ||

Schwartz RW, Tumblin TF. The power of servant leadership to transform health care organizations for the 21st-century economy. Arch Surg. 2002;137(12):1419–1427. discussion 1427. | ||

Guimarães C, Carvalho JD. Lean healthcare across cultures: state-of-the-art. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2012;2(6):187–206. | ||

Abuhejleh A, Dulaimi M, Ellahham S. Using Lean management to leverage innovation in healthcare projects: case study of a public hospital in the UAE. BMJ Innov. 2016;2:22–32. | ||

Poksinska B, Swartling D, Drotz, E. The daily work of Lean leaders–lessons from manufacturing and healthcare. Tot Qual Manage. 2013;24(7–8):886–898. | ||

Barbuto JE, Wheeler DW. Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group Organ Manage. 2006:31(3):300–326. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.