Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 15

“I Have Such a Great Care” – Geriatric Patients’ Experiences with a New Healthcare Model: A Qualitative Study

Authors Wilfling D , Warkentin N, Laag S, Goetz K

Received 7 December 2020

Accepted for publication 14 January 2021

Published 12 February 2021 Volume 2021:15 Pages 309—315

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S296204

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Denise Wilfling,1 Nicole Warkentin,1 Sonja Laag,2 Katja Goetz1

1Institute of Family Medicine, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany; 2Barmer Health Insurance, Wuppertal, Germany

Correspondence: Denise Wilfling

Institute for Family Medicine, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck, Ratzeburger Allee 160, Lübeck, 23538, Germany

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Coordinated care is important for the health and well-being of geriatric patients. However, continuity of care is lacking in many countries. Several studies have shown that case management can help to meet these requirements in health care and investigated positive effects. The project RubiN (Regional ununterbrochen betreut im Netz; Continuous care in a regional network) was developed to provide regional care- and case management for outpatient care of the elderly (age > 70 years) in a primary care setting. The aim of this qualitative approach was to explore experiences and attitudes of geriatric patients towards the newly developed complex care- and case-management intervention RubiN.

Patients and Methods: Qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of geriatric patients enlisted in the RubiN intervention networks were conducted. The collected data was transcribed and evaluated using qualitative content analysis. A deductive-inductive approach was used in generating thematic categories.

Results: Forty-four telephone interviews were performed. Two key categories were identified to describe patients’ experiences regarding care delivered by a care- and case manager (CCM), namely “role of CCM” and “changes through RubiN”. Results demonstrated that care performed by CCMs is perceived positively by geriatric patients. A main finding of this study was that geriatric patients experienced a sense of security through the care provided by CCMs. CCMs were perceived as highly competent people, having all the necessary skills to provide continuity of care.

Conclusion: This study illustrates the importance of trust between care provider and care recipient. It also shows that geriatric patients appreciate the continuous, professional care and structural and functional support provided by qualified CCMs.

Keywords: geriatric patients, care management, qualitative study, support, coordination

Introduction

Geriatric patients are often affected by several diseases.1,2 The health care system should take the needs of geriatric patients into account and guarantee continuity of care. Coordinated and supported care is important for the health and well-being of geriatric patients, otherwise they might not receive the required help. This could lead to hospitalization and rehospitalization or moving into a nursing home.3 Unfortunately, continuity of care is lacking in many countries, especially in Germany.4,5 Several studies have shown that case management can help to meet these requirements in health care and investigated positive effects for geriatric patients.6–8 Although there is no general definition of case management, it is recommended to include several interventions for assessment, care planning, coordination of care, provision of care, monitoring and evaluation, in order to meet individual patient needs.9 It can be assumed that case management operates as a kind of social support. Berkman et al show that there are two main concepts of social support.10 Firstly, structural support refers to support through a social network like family members, community members or the primary care team.10 Secondly, functional support such as emotional or informational support enhances the well-being of patients.10 Both concepts of social support could be important for geriatric patients and are integrated in the project RubiN (Regional ununterbrochen betreut im Netz; Continuous care in a regional network). It was developed to provide regional care- and case management for outpatient care of the elderly (age >70 years) in a primary care setting in Germany. RubiN was implemented in five different medical practice networks, which are located in different geographical (north, north-western, west and east Germany) and infrastructural (urban and rural) areas. The intervention consists of complex cross-sectoral, assessment-based and multi-professional care- and case management. An average number of five specially trained care- and case managers (CCMs) work in each practice network. The CCMs have a therapeutic or nursing background. The general practitioner decides if a patient has a need for care provided by a CCM. The following tasks are performed by the CCMs: assessment, coordinating, structuring and organizing health care based on the patients’ individual needs. This occurs in close collaboration with the patient’s general practitioner and regional health and social care providers. The care- and case management aims to sustain the patients’ independence regarding social involvement and the ability to remain at home for as long as possible.11

Care- and case management is a complex intervention as it includes several interacting components, and such the evaluation of these interventions is a challenging task.12 Effects of case management have been evaluated in several studies, mainly focusing on outcomes like costs, healthcare utilization, health condition, cognitive state, quality of care and patient satisfaction.9 Qualitative research is needed to identify challenges and barriers to implementation as well as supporting factors. Furthermore, it is important to explore different experiences relating to the intervention, both from the care provider and care receiver perspective. However, there is a lack of studies evaluating different perspectives of case management.9 To get these important insights, the aim of this qualitative approach was to explore experiences and attitudes of geriatric patients towards the newly developed complex care- and case management intervention RubiN.

Methods

Study Design

The present study was designed as a qualitative study to explore the experiences of patients with the newly developed care- and case management intervention. The qualitative study is based on the criteria for qualitative research.13 Therefore, qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of geriatric patients were conducted.

Sample Data and Recruitment

The study population consisted of geriatric patients enlisted in the RubiN intervention networks. Each of the five intervention networks were asked to recruit eight patients who were able to participate in an interview to determine a purposeful sample. To be included in this study the patients were required to not suffer from any cognitive impairments and had to have been enrolled for at least 12 months in the intervention networks. Geriatric patients were preselected by the staff of the RubiN intervention networks and potential patients were then contacted by telephone by NW. Before participating, each patient received oral and written information about the study concerning background, procedure, goals and privacy policies. Informed consent was obtained by a signed form in advance of participation. Each participant received a financial incentive of 50 Euros.

Data Collection

A semi-structured interview guide was developed by an interprofessional team of sociologist, health services researcher and physician. The interview guide focused on the experiences the patients had with the care which was provided to them by a CCM as well as any potential changes in their lives and health which originated from their participation in the project RubiN. Questions focused on the CCMs’ role, concerning the first contact, what offers were made through CCM, determinants of demand and experiences with care provided by CCM. Furthermore, questions aimed to explore changes through RubiN, in order to assess concrete changes and how patients experienced these changes. Data collection took place between March and July 2020. Characteristics of participants were collected during the interview (see Table 1). Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, all interviews were conducted by telephone. All interviews were conducted by the same interviewer (NW) to ensure a constant and homogeneous interview process.

|

Table 1 Sample Characteristics (n=44) |

Data Analysis

Interviews were recorded digitally, fully transcribed verbatim and anonymized. All transcripts were in German and their accuracy was validated by comparing the transcripts with the digitally recorded interviews. A qualitative content analysis was carried out on the transcripts.14,15 Content analysis is a well-known and structured approach in health care science and allows a descriptive view of health care situations from different patient perspectives. Data analysis was performed using the software MAXQDA 2020.16 Two researchers (DW (nursing background) and NW (physician background)) analyzed the transcripts independently by first paraphrasing all statements and then clustering them into meaningful categories. The research team used a deductive-inductive approach in generating categories. Categories and sub-categories were generated deductively based on the interview guide. Data was compared regularly in meetings supported by a third researcher (KG (sociologist and health services research background)) throughout the analyzing process and a consensus was reached. The category system was adjusted inductively during the analyzing process. Key issues were identified and coded independently by the research team. For publication, the participant quotations were translated from German into English.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was required for this study according to the Ethics Committee in Lübeck, Germany (Approval number: 19–282) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained through a signed consent form and included publication of anonymized responses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Overall, 44 telephone interviews were performed. The study sample consisted of n=30 female and n=14 male participants. The mean age was 81.4 (± 4.7). The duration of interviews varied and was on average 27.4 minutes (Min= 10 minutes; Max=76 minutes). Characteristics of participants of each intervention network are shown in Table 1.

Key Categories

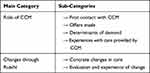

Two key categories were identified in the telephone interviews to describe the patients’ experiences regarding the care delivered by CCMs, namely “the role of CCM” and “changes through RubiN”. Key categories are divided into different sub-categories. The main category “role of CCM” included four sub-categories and “changes through RubiN” included two sub-categories (see Table 2). The statements of all patients were taken into account.

|

Table 2 Main Categories and Sub-Categories |

Role of CCM

First Contact with CCM

The first contact between patient and CCM was described in a similar way. Most of the patients were first contacted by the CCM via telephone. As part of this conversation, a brief presentation of the project RubiN was given and a date for the first home visit was decided.

Yes, we have arranged a visit. They asked if they could come, […] why not? I mean, it can only be an advantage if someone who is familiar with this topic deals with your situation and can give advice. (TN28)

The aim of the first visit at home was to assess the current health status and care situation in order to determine whether or not they required help.

[…] even got an idea of me, of my living conditions, how I feel, what kind of help I need, that was the first contact. (TN7)

Offers Made

As part of project RubiN, the CCM carried out different activities. Depending on individual needs, the CCM supported patients in a wide variety of matters. The main focus was providing assistance in applying for support and funds (eg, care level, home care services, pass for (severely) disabled persons, etc.).

[…] together we achieved a lot, for example a shower board. […] and then we filled out the ID card for handicapped persons, and we got it, so I have to say, I have to thank Mrs. […]. (TN11)

Patients also received support in finding a nursing home (eg, for a relative), an age-appropriate apartment and were supported in applying for a cure. The CCM offered the opportunity to join regional sports groups for aged people as well as giving instructions for coordination and relaxation exercises for the implementation at home.

Yes, she has picked out everything suitable for me. That I can meet other people, too. Or maybe some easy training offers. (TN17)

Furthermore, the CCMs also provided advice on age-appropriate living space design (eg, handrail in the shower) and the associated application for funds.

Determinants of Demand

Whether services provided by a CCM were used depended on various determinants. Patients felt motivated to contact their CCM because they knew that they would get an honest and competent answer. They did not have a feeling of being put off or that their concerns were pushed back.

Because I get an honest and decent answer. I am not put off, pushed back or anything. On the contrary, we can speak freely. (TN28)

Patients stated the feeling that they could address everything at any time, and that the CCM always cared. The interviews did not reveal any significant barriers to the use of the offers and assistance presented by CCMs. Patients stated that the only reason why they did not use certain services was that there was no need at the time.

Nothing prevents me. If something happens, and I will think: Oh, I would need help, I would call her […]. (TN39)

Experiences with Care Provided by CCM

Patients described their personal experiences with the care provided by CCMs. All patients stated to be very satisfied with the care delivered by CCMs. Through regular contact with CCMs, patients got a feeling of being safe because they had someone listening to them. If they had any questions or concerns, they could contact CCM at any time. The feeling of having someone constantly by their side was perceived as very positive.

Yes, I would say, very good. […] you also feel secure and heard, you know? […] You feel safer when you are alone, you know? The children don’t take care of you and, and you know that you are really in good hands […]. (TN1)

Patients reported that the CCM always took the time to listen to problems, even if they were busy because they had to visit many patients. CCMs were seen as very competent, because they have all necessary skills, eg, comforting, listening and paying attention to the patients, handing out advice and always in a personal manner.

I think it’s great. She is a very competent woman, very friendly, lovely, understanding and apart. Although she is very busy, she takes the time. So, I am very satisfied. She addresses the … everything! How I feel and so on, yes. It is, it is really nice! (TN2)

Changes Through RubiN

Concrete Changes in Care

Not all patients experienced changes from the care delivered by RubiN. It was rather difficult for patients to name specific changes. Some patients stated that they could not name any changes, because they did not use the offered services, as there was only little need for support so far. But even patients who reported in advance that they used several services stated that they did not notice any changes in their care. Still, some patients did report that RubiN had improved their care.

Yes, that I get better care here, […] which wasn’t the case before. (TN10)

The most reported change was that patients did not feel alone any longer, and that they had the feeling that someone was taking care of them.

That I don’t feel alone, that I always have someone to talk and who really helps me in an emergency. If I get really sick, I am sure Mrs. […] will take care of me. (TN34)

Evaluation and Experiences of Change

Patients reported how they experienced this change. All patients who noticed changes in their care through RubiN perceived these changes as very positive. Patients reported a sense of security because they had a person to contact if questions arose. The possibility to call at any time was very much appreciated.

I can’t imagine anything better. So I can’t say how grateful I am to her […] with what kind of attention and dedication, even If I call and don’t reach her, […] I get a call back immediately […], so that works great. (TN19)

The certainty of having someone to contact if help is needed also had a positive impact on the mental health of the patient. Patients reported that they were happier and more motivated.

That I’ve become a completely new, a completely new person. That I have a completely new life, that I am much happier. That I simply dared a new beginning! Ms. […] supported me. Giving me the courage to do so! (TN21)

Discussion

The aim of this qualitative approach was to explore experiences and attitudes of geriatric patients regarding the new developed complex care- and case management intervention RubiN. The data compiled by this study is particularly important to get a deeper understanding of care- and case management interventions and how this kind of intervention could have an impact on patient’s life. The results demonstrated that care performed by CCMs is perceived positively by geriatric patients. A main finding of this study is that geriatric patients experience a sense of security through the care provided by CCM. It must be considered that many older people are living alone. Either they have no family whatsoever or their family members live far away. Furthermore, many older people are taking care of a spouse and therefore have limited social contacts and a reduced social life. This feeling of security also has an impact on the mental health and as a further result, patients get empowered.17 These results are in line with the results from Hjelm et al 2015, where participants stated to experience a trusting relationship with case managers, who made them feel more secure that they would cope with future concerns.18 Similar results were found in other international reports,9,19 where authors revealed the meaning of implementing psychosocial support into case management models for geriatric patients.

Furthermore, social support plays a key role in holistic and patient-centered approaches, and it is known that social relationships have an essential effect on health, especially on mental health. The CCM is a person who provides structural support to the patients and provides access to potential resources in order to improve the patients’ health status in terms of functional support as theoretically stated by Berkman et al 2000.10

Moreover, another interesting result was how CCMs are seen by care recipients. Participants in this study reported that CCMs are perceived as highly competent persons, having all necessary skills to provide continuity of care. Participants in Hjelm et al 2015 described case managers to be very fit in their job.18 One possible explanation could be that CCMs have a medical background (eg, nurse, medical technical assistant) and had special training as case and care managers. As a result, CCMs have a wide range of skills.

Furthermore, participants in both studies appreciated that case managers took the time to listen to their problems. Especially at the beginning of the care collaboration, CCMs took the time to assess the current health status and care situation, in order to plan and organize further steps.18 Patients really appreciate this commitment. It becomes clear that CCMs provide holistic care but are still individual and needs-oriented. Moreover, many patients reported that they enjoyed the visits from CCM very much and looked forward to them. The open discussions were very valuable to the patients. Also, Balard et al 2016 reported that case managers are often seen as a “friend” by older patients.20

Although most patients perceive the care provided by CCMs as very positive and helpful, there were some patients who did not use the offered services. The reason given was that there was no need so far. However, the well-known phenomenon that older people often refuse help of health and social care services must be considered. Unfortunately, the refusal of professional help often contributes to an admission in hospital or nursing home which could have been potentially avoided otherwise.21

Another explanation could be that not all patients involved in this study are those in the greatest need of help. Previous studies still reported the challenge of recruiting patients suitable for the evaluation of a case management intervention.8,18

Limitations

A strength of this qualitative study was that interviews were conducted and analyzed by independent interviewers and researchers in order not to bias the results in any way. A potential limitation is that only patients from the intervention networks may have agreed to participate in the study. Furthermore, only medical practice networks participating in the study were included for this qualitative approach and general practitioners decided which patient should receive care provided by CCM. Therefore, information from other medical practice networks are missing and results cannot be generalized. Each participant received a financial incentive of 50 Euros, which is a bias that needs to be taken into account. However, the results provide good insight into the patients’ experiences with the newly developed health care model.

Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed an important factor for the successful implementation of care- and case management. This study illustrates the importance of trust between care provider and care recipient. It also shows that geriatric patients appreciated the continuous, professional care and structural and functional support provided by qualified CCM. As a result, the patients feel more confident and secure. It seems that trust and continuity are essential elements for successful implementation of case management interventions. Consequently, if a solid basis of trust can be built between the patient and the CCM, case management is an effective intervention of care of geriatric patients.

Abbreviations

RubiN, Regional ununterbrochen betreut im Netz; Continuous care in a regional network; CCM, case- and care managers.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients participating in the interviews.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Stiel S, Krause O, Berndt CS, Ewertowski H, Müller-Mundt G, Schneider N. Caring for frail older patients in the last phase of life. Challenges for general practitioners in the integration of geriatric and palliative care. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;53(8):763–769. doi:10.1007/s00391-019-01668-3

2. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing: 1950–2050; 2014. Available from: WPA2015_Report.pdf(un.org).

3. Golden AG, Tewary S, Dang S, Roos BA. Care management’s challenges and opportunities to reduce the rapid rehospitalization of frail community dwelling older adults. Gerontologist. 2010;50(4):451–458. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq015

4. Gensichen J, Beyer M, Schwäbe N, Gerlach F. Hausärztliche Begleitung von Patienten mit Depression durch Case Management-Ein BMBF-Projekt. ZFA. 2004;80:507–511. doi:10.1055/s-2004-832426

5. Schneider A, Donnachie E, Tauscher M, et al. Costs of coordinated versus uncoordinated care in Germany: results of a routine data analysis in Bavaria. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011621. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011621

6. Sheaff R, Boaden R, Sargent P, et al. Impacts of case management for frail elderly people: a qualitative study. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;14(2):88–95. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007142

7. Low LF, Yap M, Brodaty H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:93. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-93

8. You E, Dunt D, Doyle C, Hsueh A. Effects of case management in community aged care on client and carer outcomes: a systematic review of randomized trials and comparative observational studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:395. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-12-395

9. Sandberg M, Jakobsson U, Patrik Midlöv P, Kristensson J. Case management for frail older people – a qualitative study of receivers’ and providers’ experiences of a complex intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:14. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-14

10. Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843–857. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4

11. Laag S, Sydow H, Klähn AK, et al. Transferorientiert fördern: ein RubiN auf Rezept. [Transfer-oriented support: a prescription for RubiN]. Gesundheits und Sozialpolitik. 2019;73(6):36–42. doi:10.5771/1611-5821-2019-6-36.German.

12. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluation complex interventions: the new medical research counsil guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:587–592. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010

13. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

14. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology.

15. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

16. MAXQDA, Software für qualitative Datenanalyse, 1989 – 2020, VERBI Software; 2019. Consult. Sozialforschung GmbH. Berlin, Deutschland.

17. Ng N, Santosa A, Weinhall L, Malmberg G. Living alone and mortality among older people in Västerbotten County in Sweden: a survey and register-based longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:7. doi:10.1186/s12877-019-1330-9

18. Hjelm M, Holst G, Willman A, Bohman D, Kristensson J. The work of case managers as experienced by older persons (75+) with multi-morbidity – a focused ethnography. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:168. doi:10.1186/s12877-015-0172-3

19. Sargent P, Pickard S, Sheaff R, Boaden R. Patient and carer perceptions of case management for long-term conditions. Health Soc Care Community. 2007;15(6):511–519. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00708.x

20. Balard F, Gely-Nargeot MC, Corvol A, Saint-Jean O, Somme D. Case management for the elderly with complex needs: cross-linking the views of their role held by elderly people, their informal caregivers and the case managers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:635. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1892-6

21. Joseph Rowntree Foundation. From Welfare to Well-Being: Planning for an Ageing Society. York, UK: Author; 2004.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.