Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 10

Improving urban environment through public commitment toward the implementation of clean and healthy living behaviors

Authors Hartini N , Ariana AD , Dewi TK , Kurniawan A

Received 2 December 2015

Accepted for publication 20 January 2017

Published 16 March 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 79—84

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S101727

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Nurul Hartini, Atika Dian Ariana, Triana Kesuma Dewi, Afif Kurniawan

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Background: Some parts of northern Surabaya are slum areas with dense populations, and the majority of the inhabitants are from low-income families. The condition of these areas is seemingly different from the fact that Surabaya city has won awards for its cleanliness, healthy environment preservation, and maintenance.

Aim: This study aimed at turning the researched site into a clean and healthy environment.

Methods: The research was conducted using a quasi-experiment technique with a non-randomized design and pretest–posttest procedures. The research subjects were 121 inhabitants who actively participated in the public commitment and psychoeducation program initiated by the researchers to learn and practice clean and healthy living behaviors.

Results: The statistical data showed that there was a substantial increase in the aspects of public commitment (t-value = 4.008, p = 0.001) and psychoeducation (t-value = 4.038, p = 0.001) to begin and maintain a clean and healthy living behaviors.

Conclusion: A public commitment in the form of a collective declaration to keep learning and practicing a clean and healthy living behaviors were achieved. This commitment followed by psychoeducation aimed at introducing and exercising such behaviors was found to have effectively increased the research subjects’ awareness to actively participate in preserving environmental hygiene. Developing communal behaviors toward clean and healthy living in inhabitants residing in an unhealthy slum area was a difficult task. Therefore, public commitment and psychoeducation must be aligned with the formulation of continuous habits demonstrating a clean and healthy living behaviors. These habits include the cessation of littering while putting trash in its place, optimizing the usage of public toilets, planting and maintaining vegetation around the area, joining and contributing to the “garbage bank” program, and participating in the Green and Clean Surabaya competition.

Keywords: urban clean and healthy environment, public commitment, clean and healthy living behavior learning

Background

Surabaya is one of the urban and metropolitan cities in Indonesia which is concerned with clean and green living. It has continuously shown a positive development in this field. Surabaya has won several awards related to environmental and hygienic issues. For instance, the Indonesian national award “Adipura” has been awarded to Surabaya by the President of Indonesia since 2006. Another achievement was the United Nations international award for Taman Bungkul being named the best urban park in 2014. Additionally, Surabaya was the recipient of the international award of the European Business Assembly as an Innovative City of the Future in 2014.

Since 2005, Surabaya has developed a program to maintain and preserve the environment, known as the Green and Clean program. The Green and Clean program has been aimed at transforming Surabaya into a beautiful, independent, and healthy city. The objective of this competition was to elect areas of the city that demonstrate a clean and healthy environment as award recipients. This competition is held annually, and every area in Surabaya is eligible to participate. However, Surabaya, like many big cities, still has some slum areas with highly populated and underprivileged residents who mostly come from low-income families. These areas, located in the northern part of Surabaya, are in need of greater attention and transformation. The condition of this region is considered unhealthy and detrimental to the residents’ health. The community or public health is not optimal due to a number of factors, such as the environment, human behavior, health care services, and genetics.1

Cuellar and Paniagua2 suggest that community issues can be solved through a community-based intervention. In this study context, it means that a community-based intervention is necessary to change slums in the researched site into clean and healthy residential areas. The head of the North Surabaya regency stated that sanitation and health are two of the many priority programs happening in the region. In efforts to improve environmental hygiene and health in this area, some facilities have been built to support the regional government’s goals on these issues. These facilities include the implementation of a public toilet program in some parts of this area targeting most of its inhabitants who do not own a toilet in their houses. The head of the North Surabaya regency and his team also suggested, and hoped for, a third party and/or university to participate and contribute in their community development, particularly in hygiene and health programs. A series of discussions that involved several parties were then established. These parties consist of local authorities of the northern Surabaya regency, its resident representatives, and the third parties, in this case represented by Wahana Visi Indonesia and Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga. All of these members of the discussion meetings agreed on implementing public commitment and on participation in psychoeducation aimed at practicing and maintaining a clean and healthy living behaviors. The efforts signify a form of community-based intervention to increase the environmental hygiene and promote a clean and healthy living.

In promoting a hygienic and healthy behaviors effectively, action is required from individuals and communities in order to gain strong public commitment, policy support, social acceptance, and systemic backing. This public commitment, motivated by local values and wisdom, aims to collectively build the community’s awareness to be the main actors/partners in creating a clean and healthy urban environment. According to Inauen et al,3 the true manifestation of a decision lies in the implementation of a commitment to act and maintain such action. A decision derives from an intention/perception, followed by plans on when, where, and how the intended behaviors should be implemented. In the context of hygienic and healthy living behaviors, Inauen et al3 emphasize that a commitment to engage in such behavior is exhibited through individuals’ rigorous reinforcement of their intention and action. For those who are committed, being able to perform in this way is urgency or a need. They would be satisfied when they display the healthy living behaviors and would be disappointed and irritated if they fail to do so.3

In regard to the public commitment, a study by Munson et al4 illustrated a substantially positive effect of public commitment on a physical activity program that indicates healthy behaviors. This study compared commitments available publicly and privately. They examined personal but publicly available statements of commitment posted on social media including the ones written through emails. Then, they compared these to the ones kept in private. The result showed that participants who posted their statements of commitment in social media participated in the physical activity program longer than those who made private commitment without any form of publication. In order to achieve a public commitment, clear and detailed objectives must be set. This is imperative because unclear prospectus and public reporting can reduce the motivation for healthy living behaviors.4

The role of psychoeducation in this study is essential to stimulate and train one’s behavior in order to increase knowledge, attitude, and behavior in terms of clean and healthy living behaviors. A study by Aldcroft et al5 found that an intervention using psychoeducation was able to generate a significantly positive impact on the physical activity level, for instance, dietary habits or healthy diet choices, and the process of quitting smoking. Psychoeducation deals with planning management, problem-solving, self-monitoring, and the appearance of individual perception and attitude that can be looked upon as a role model.5

A clean and healthy urban environment has become one of the priority programs for increasing the quality of human development and resources in Indonesia.6 Cloninger7 suggests that this type of environment is fundamental for children to learn behaviors in a way that supports a clean and healthy living at an early age. Children who live in unhealthy slums would not be able to visualize, manage, and practice clean and healthy living, even though they get an intensive lesson at school concerning the issue.

Methods

This research used a quasi-experiment method with a pretest–posttest design and non-randomized sampling technique.8–10 The residents of North Surabaya were made to implement a public commitment and given psychoeducation related to clean and healthy living behaviors. The public commitment was aimed at building trust and providing a pledge to motivate the community’s involvement to adopt a clean and healthy lifestyle. This technique was expected to be effective because a public commitment is an element of a health promotion model that considers the socioecological aspects.11,12 Public commitment in this context means a collective declaration to pledge for a hygienic and healthy environment as part of daily living of the individuals and community. Psychoeducation in this study refers to a psychological education for the community to achieve the shared goal of a clean and healthy urban environment.

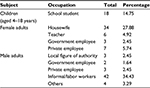

The research subjects were the residents of North Surabaya, consisting of children, elders, local authorities, and other figures in the community. In detail, the total participants were 122 inhabitants whose characteristics are described as follows.

Table 1 shows the subjects included in this study. The subjects were divided into three categories: children (aged 4–18 years), female adults, and male adults. Those three subject categories were then divided based on their occupation. The children who participated in this study were classified as students. There were 18 students, and they made up 14.75% of the whole subjects. The female subjects were grouped under four types of occupations: housewife, teacher, government employee, and private employee. The housewife category formed the largest percentage (27.88%) of the whole participants. There were six teachers, and this made up 4.92% of the entire subjects. Only three were government employees in this research which equaled to 2.45% of the whole participants. There were seven private employees which made up 5.74%. From the table, it can be seen that housewives formed the biggest group among the female research subjects.

| Table 1 Research subjects |

The last subject category was the male participants. They were divided into five categories based on their occupation. There were three men whose occupation was listed as local figures of authority. They made up 2.45% of the group. The two government employees made up 1.64% of the whole group. There were three men working as private employees who made up 2.45% of the group. Additionally, there were 42 participants working as laborers who contributed to 34.43% of the group. The proportion of men working in other occupations was 3.29% of the total. From the table, it can be concluded that the informal/labor workers formed the biggest group of participants in the research.

The data were collected both prior and after the intervention using questionnaires. The public commitment questionnaire consisted of five items focusing on the evaluation of the level of the community’s awareness to contribute in environmental hygiene. The psychoeducation questionnaire consisted of 25 items focusing on the assessment of individuals’ understanding related to clean and healthy living. The questions on the topic of clean and healthy living in the questionnaire conducted prior to and after the psychoeducation included putting garbage in the proper places, optimizing the function of public toilets, planting and maintaining the vegetation area, contributing to the “garbage bank” program, and participating in the Surabaya Green and Clean competition. Both questionnaires used in this research had been reviewed by experts for their content validity.

Analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using a paired-sample t-test to examine behavioral differences prior to and after the intervention of public commitment and psychoeducation, particularly on clean and healthy urban living. The analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 16.0 for Windows.

Declaration

Ethics approval was obtained from The Board of Ethics, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Airlangga, prior to the study. All participants were required to give their written consent before participating in this study.

Results

The results of the paired-sample t-test showed a substantial increase. The statistical results illustrated a significant increase in public commitment (t-value = 4.008, p = 0.001) and psychoeducation (t-value = 4.038, p = 0.001) to adopt and maintain clean and healthy living behaviors. Since the research, the public commitment has established a widely positive impact on northern Surabaya residents. This is indicated by the increasing phenomenon of the residents’ awareness that individual and environmental hygiene was to be part of their daily behaviors. Thus, psychoeducation about clean and healthy living has indirectly shaped positive behaviors in the residents. For instance, residents conduct some voluntary work where they clean the surroundings together once a month. Mothers and their children demonstrated a firm attitude to restrict fathers from smoking inside the house. Further impact of this community-based intervention was the involvement of children aged 6–12 and 12–18 years who volunteered to water the vegetation in the afternoon to look after their environment. More positive effects can also be seen among the housewives. They plant vegetables and fruit in their houses and maintain the cleanliness of the water sewage system in their environment by regularly cleaning the gutter.

The involvement of every element of the community in clean and healthy living behaviors is expected to change these slum areas into a clean, beautiful, and green space. This significant change into clean and healthy behaviors in the community signifies a behavioral transformation. Further changes include throwing garbage in its proper place (t-value = 2.236, p = 0.041), participating in the “garbage bank” program (t-value = 0.565, p = 0.048), participating in the Surabaya Green and Clean competition (t-value = 1.861, p = 0.033), optimizing the function of public toilets (t-value = 1.464, p = 0.016), as well as planting and maintaining the vegetation in their surrounding areas (t-value = 1.484, p = 0.006).

Discussion

Forming a clean and healthy living habit should start as early as the childhood period in order to familiarize and internalize certain behaviors that would support the love for the environment. The efficacy of character building, however, should not be entirely relied upon at the school alone to achieve the goals. In this sense, the learning process should begin and continue at home. Thus, it becomes a difficult task when children do not see and practice what they learn at school where they live. Developing the intended habit would be more challenging especially to those who reside in unhealthy slum areas. For instance, a child will find it hard to learn how to dispose of garbage properly if he/she lives in a cluttered and littered residential area. This is consistent with the finding of a study by Sholihah and Anwar1 investigating the effect of home hygiene in Marabahan, Kalimantan. Their study showed that the impact would be more optimal when various parties, starting from the residents to the government, were all involved in the process.

Psychoeducation was part of the groundwork for providing a conduit to understand and exercise the intended behaviors to support the goals of this study. Psychoeducation includes a clinical-based and practical model consisting of training in ecology, behavior and cognition, learning theories, practice in group, stress management, social support, and narrative approach.13 Through such ecological approaches, psychoeducation is expected to offer and stipulate a framework to specify and deliver the objectives and help people understand the importance of healthy living from their experience in the environment, within the family, or at school, or in the local government. Cognitive-behavioral approaches, such as problem-solving and role-playing, can enhance children’s understanding to accept and make sense of new information about healthy living, as well as to implement this in the long term.

According to Klingman,14 psychoeducation refers to psychologist’s/counselor’s capability to educate individual(s) with psychological knowledge and skills relevant to one’s development and health. It is also expected that this training would equip individuals with competences to effectively act and adjust when a problem emerges. Based on this study result, psychoeducation evidently improved the behavior of clean and healthy living in the research subjects. This finding is in line with a study by Zikrillah et al who found that psychoeducation positively affected family’s skills to overcome psychosocial problems. These skills were the result of the allocated psychoeducational intervention.15

Klingman14 elaborates that psychoeducation differs from traditional counseling. In this respect, psychoeducation is cognitively and psychologically oriented knowledge that purports to effectively solve problems at hand. It encompasses skills in designing the psychoeducational framework, capabilities to clearly communicate the knowledge, and competences to stimulate the emergence of intended behaviors. In addition, psychoeducation can be implemented for prevention, optimization, or curative goals. This is consistent with the current research finding in which psychoeducation optimized the research process and was able to accomplish the objectives of this study. In this case, it was to stimulate clean and healthy living behaviors.

This research also proved that the level of public commitment rose significantly, and this resulted in the increase of the community’s awareness on clean and healthy living. Some prior studies also found that public commitment had effects on improving health behaviors, such as weight loss and diabetes-preventive behavior.16,17 There are additional explanations on how commitment can serve as a promoter of health behavior.

Cialdini18 suggests that commitment may influence behavior through changes in self-image or self-concept. When individuals make a commitment to endorse a behavior, they will likely change their self-concept in line with the commitment.19 This change in self-concept is what eventually drives individuals to behave in a consistent fashion with the commitment they make beforehand. Another explanation for the effect of commitment is that commitment results in an individual’s attitude shift, which later shapes the behavior according to the commitment.17 Particularly, writing down a commitment can make an individual change his/her attitude because a written statement is generally associated as the writer’s true attitude.18

In the current research, the type of commitment used was public commitment. Public commitment can increase one’s motivation to behave in accordance with the commitment.18 This is because individuals are inclined to try to look consistent in the eyes of others, and violating a commitment made in public may potentially cause social sanction for the individuals.16,19 Thus, publication of commitment to endorse health behaviors can heighten one’s motivation to keep the commitment.

The government also sustainably attempts to support clean and healthy urban environments in North Surabaya. The findings of this research can be used by the government to heighten the effectiveness of their attempts. According to the research finding, which has been backed up by theoretical review, we suggest that psychoeducation should be used in conjunction with solving the existing problem, designed in a structure suitable for the target participants and in a communicative way. Through this approach, the design can be easily understood and implemented. With regard to commitment, Lokhorst et al19 list some viable strategies to optimize the effectiveness of commitment in shaping behavior. First, commitment should be made public and voluntarily.18 Written commitment has been proven to be the most effective.19 Commitment also ought to be made specific and salient so that individuals know what behavior is expected and when they should do it. Using commitment along with other interventions, like in this research, is also a recommended procedure to bring about a long-term behavioral change.19

Limitations

The limitation of the current study is the variation in research subjects’ age, level of education, and socioeconomic status, which affect their level of comprehension concerning clean and healthy living behaviors. The community’s comprehension about the indicators of a clean and healthy environment varied, and hence the variation in active contribution in public commitment and psychoeducation. Also, the measuring instruments, which were questionnaires, may have allowed the respondents to provide superficial answers or statements of what might be expected by their community.

Conclusion

Public commitment on a communal declaration to endorse clean and healthy living behaviors, followed by psychoeducation on the clean and healthy living, was found to be effective in raising the residents’ awareness to participate actively in improving environmental hygiene. Educating communities of unhealthy slums on how to develop clean and healthy living behaviors is not easy. Therefore, public commitment and psychoeducation shall be followed by the development of clean and healthy living habits in the community, such as disposing garbage properly, optimizing the function of public toilets, planting and keeping vegetation around the area, contributing in the “garbage bank” program, and participating in the Surabaya Green and Clean competition. The government’s role in urban planning, particularly in building physical facilities, is one focal factor which will support the development of such clean and healthy environments in North Surabaya.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sholihah Q, Anwar S. Effect of household life behavior to clean and healthy life in district Marabahan, Barito Kuala. J Appl Environ Biol Sci. 2014;4(7):152–156. | ||

Cuellar I, Paniagua AF. Handbook of Multicultural Mental Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. | ||

Inauen J, Tobias R, Mosler HJ. The role of commitment strength in enhancing safe water consumption: mediation analysis of a cluster-randomized trial. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19:701–719. | ||

Munson SA, Krupka E, Richardson C, Resnick P. Effects of public commitments and accountability in a technology-supported physical activity intervention. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY: ACM Publication; 2015. | ||

Aldcroft SA, Taylor NF, Blackstock FC, O’Halloran PD. Psychoeducational rehabilitation for health behavior change in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2011;31(5):273–281. | ||

Danim D. Transformasi Sumber Daya Manusia [Transformation of Human Resources]. Jakarta: Bumi Aksara; 1996. Indonesian. | ||

Cloninger SC. Theories of Personality: Understanding Persons. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2004. | ||

Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH. Social Support Measurement and Intervention. A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. | ||

Singarimbun, Effendi. Metode Penelitian Survey, Cetakan Kedua [Survey Research Methodology, 2nd ed]. Jakarta: LP3ES; 2003. Indonesian. | ||

Sugiyono. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif Kualitatif dan R & D [Quantitative-Qualitative Research Methodology and R&D]. Bandung: Alfabeta; 2010. Indonesian. | ||

Bartholomew KL, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Intervention Mapping: Designing Theory- and Evidence-Based Health Promotion Programs. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 2001. | ||

Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield; 2005. | ||

Lukens E, McFarlane W. Psychoeducation as evidence-based practice: considerations for practice, research, and policy. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2004;4(3):205–225. | ||

Klingman A. Psychoeducation: applications in community health education settings. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1986;7(1):51–60. | ||

Zikrillah, Lukman M, Setiawan R. Pengaruh Psikoedukasi terhadap Masalah Psikososial Keluarga yang Memiliki Anggota Keluarga dengan Masalah Kesehatan Kronis: Sebuah Literature Review [The Effect of Psychoeducation on Psychosocial Diffiuclties of Families that Have Member with Chronic Health Condition: A Literature Review]. Medisains: Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Kesehatan. 2016;14(2):26–31. | ||

Nyer PU, Dellande S. Public commitment as a motivator for weight loss. Psychol Mark. 2010;27(1):1–12. | ||

DeBar LL, Schneider M, Drews KL, et al; HEALTHY Study Group. Student public commitment in a school-based diabetes prevention project: impact on physical health and health behavior. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:711. | ||

Cialdini RB. Influence: Science and Practice. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. | ||

Lokhorst AM, Werner C, Staats H, van Djik E, Gale JL. Commitment and behavior change: a meta-analysis and critical review of commitment-making strategies in environmental research. Environ Behav. 2013;45(1):3–34. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.