Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 14

Increased Risk of Pyogenic Liver Abscess after Endoscopic Sphincterotomy for Treatment of Choledocholithiasis

Authors Wu CK , Hsu CN , Cho WR, Yang SC, Liu AC, Tai WC , Lee CH, Yang YH , Chuah SK , Liang CM

Received 24 March 2021

Accepted for publication 11 May 2021

Published 8 June 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 2121—2131

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S312545

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Prof. Dr. Héctor Mora-Montes

Cheng-Kun Wu,1 Chien-Ning Hsu,2,3 Wei-Ru Cho,1 Shih-Cheng Yang,1 An-Che Liu,4 Wei-Chen Tai,1 Chen-Hsiang Lee,5 Yao-Hsu Yang,6– 8 Seng-Kee Chuah,1 Chih-Ming Liang1

1Division of Hepato-Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; 2Department of Pharmacy, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; 3School of Pharmacy, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; 4Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; 5Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung, Taiwan; 6Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan; 7Health Information and Epidemiology Laboratory of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chiayi, Taiwan; 8School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan

Correspondence: Chih-Ming Liang

Division of Hepato-Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and Chang Gung University College of Medicine, 123, Dabi Road, Kaohsiung, 833, Taiwan

Tel +886-7-731-7123, ext. 8301

Fax +886-7-732-2402

Email [email protected]

Background and Aim: Endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) abolished the barrier between the hepatobiliary system and duodenum and might be at risk of pyogenic liver abscess (PLA). We aimed to identify the association factors of PLA in patients who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures for treatment of choledocholithiasis.

Methods: This study was based on the Chung Gung Research Database (CGRD) between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2018. Those who had an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision (ICD9 and ICD10) codes of choledocholithiasis and received ERCP were enrolled. After strict exclusions, 11,697 patients were further divided into the endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) group (n=7,111) and other ERCP group (n=4,586) for analysis.

Results: Patients receiving ES had significantly higher rates of PLA than those of the other ERCP group (5-year cumulative incidence 2.4% versus 1.7%; 10-year cumulative incidence 3.9% versus 3.2%, log-rank p=0.0177). Aging, male gender, surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system and hepatobiliary malignancy were significant association factors of PLA. On multivariate analysis, the ES increased the risk of PLA (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=1.49; 95% CI=1.12– 1.98; p=0.0058) but decreased the risks for acute pancreatitis (aHR=0.72; 95% CI=0.60– 0.85; p=0.0002) and cholangitis (aHR= 0.91; 95% CI=0.84– 0.99; p=0.0259). There was no significant difference about recurrent choledocholithiasis between groups.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated a significant risk of PLA after patients receiving ES compared with the other ERCP group. We should also carefully monitor the association factors of PLA after ERCP treatment of choledocholithiasis including aging, male gender, surgery for the hepato-pancreato-biliary system and hepatobiliary malignancy.

Keywords: pyogenic liver abscess, endoscopic sphincterotomy, choledocholithiasis, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) is widely applied as the standard management of bile duct stones.1,2 Although generally considered safe, ES still carries some risks of complications. The short-term complications include procedural bleeding, pancreatitis, cholangitis, and perforation, whose overall incidence ranges from 2.5– 13.1%.3–7 As for long-term complications, Oliveira-Cunha et al8 reported the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma varied from 0–3.1% between studies, the rate of recurrent choledocholithiasis from 3.2–22.3%, and low incidence of cholangitis in the absence of recurrent biliary stones.

Pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) is a potential life-threatening infectious disease. Recently, biliary tract diseases including choledocholithiasis, hepatobiliary malignancy, stricture, and congenital biliary anomalies become the predominant etiologies of PLA.9 Diabetes mellitus (DM), underlying hepatobiliary or pancreatic disease, and gastrointestinal cancers with biliary tract involvement are well-known risk factors for PLA.10–12 Prior ES procedure promotes duodenal-biliary reflux and may induce ascending bacterial colonization or even infection of the common bile duct (CBD).13,14 Theoretically, ES might be associated with development of PLA. To date, there has been a lack of comprehensive study associating the risk of PLA with ES.

Therefore, we conducted a population-based, cohort study from the Chang Gung Research Database to analyze the risk of PLA among patients undergoing an ES procedure, as well as other complications including pancreatitis, cholangitis, and recurrence of CBD stones.

Methods

Compliance with Ethical Requirements

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Taoyuan in Taiwan (permitted number 201900919B0C601). This study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed consent for this study, and the data were analyzed anonymously. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Sources

We collected the patient data from the Chang Gung Research Database (CGRD), the largest hospital system in Taiwan. The CGRD is a de-identified database based on detailed medical records including outpatient and inpatient treatment, laboratory data, interventional procedures, and prescription of medication. The diseases are identified based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) for data before 2016 and ICD-10-CM for data thereafter. To protect the patients’ privacy, the data are encrypted and de-identified when entered into the CGRD and can be further decrypted for medical information if needed. According to a previous validation study,15 the CGRD contains more severe co-morbidities and higher prevalence of certain diseases than in the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database. Therefore, the CGRD is more convincing in studying complicated or rare diseases.

Study Cohort, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

The identifications of disease according to codes of ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM based on ≥1 claim of inpatients or ≥1 claims of outpatients in 1 year are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Those who had procedure codes including endoscopic sphincterotomy or endoscopic sphincterotomy with stone removal (56031B, 56033B, 56040B) were classified as endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) group. Those who did not receive ES, but had other endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) procedures such as endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage or endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage and endoscopic retrograde pancreatic drainage (33033B, 33024B, 56032B, 56020B, 56021B) were classified as the other ERCP group. Those who had a combination of ES and other therapeutic procedures were classified as the ES group. Figure 1 showed a schematic flowchart of the study design. The cohort of patients with choledocholithiasis and received ERCP procedures was identified between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2018. Those aged <18 years old, with a history of receiving ERCP procedure, pyogenic liver abscess, amebic liver abscess, alcoholism, history of surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system and malignancy including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), malignant neoplasm of gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts, malignant neoplasm of small intestine including duodenum and malignant neoplasm of pancreas were excluded before the index of choledocholithiasis. The eligible patients were then divided into the endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) group (n=7,111) and other ERCP group (n=4,586) for further analysis.

|

Figure 1 Schematic flowchart of the study design. Abbreviations: ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; ES, endoscopic sphincterotomy. |

Study Outcomes

The definition of primary and secondary outcomes is shown in Supplementary Table. The primary outcome was the occurrence of liver abscess. All patients were followed from the index hospital admission to liver abscess, death, or end of following time on December 31, 2018, whichever came first. Besides, the complications related to liver abscess such as endophthalmitis, brain abscess, intra-spinal abscess, brain meningitis, lung abscess, osteomyelitis and prostate abscess were also collected for analysis. The complication of liver abscess was defined as occurrence of infectious events in the same hospitalization.

The secondary outcomes included the occurrence of acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, recurrence of common bile duct stones <180 days or ≧180 days and in-hospital mortality rates.

Confounder Assessment

As shown in Supplementary Table S1, patient’s underlying comorbidities were identified based on ≥1 claim of inpatients or ≥1 claims of outpatients in 1 year prior to the index hospitalization, which included liver cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes mellitus (DM), disorders of lipoid, coronary artery disease (CAD), and hypertensive cardiovascular disease (HCVD).

The potential medications influencing the outcomes were collected according to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code and are shown in Supplementary Table S1, which included nonsteroidal anti-Inflammatory drugs (NSIADs)/Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin, dipyridamole, cilostazol, systemic steroids, anti-hypertensives (diuretics, beta blocking agents, calcium channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI)/angiotensin receptor blockers(ARB)), ursodeoxycholic acid, statin (atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pitavastatin, rosuvastatin and simvastatin), and other Lipid lowering drugs (clofibrate, bezafibrate, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate, nicotinic acid, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, nicotinic acid and derivatives and other lipid modifying agents).

Interventional procedures or diseases that occurred during the follow-up period possibly influencing the outcomes were also collected for further analysis, which included endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD), endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD), surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system, cholecystectomy and hepatobiliary malignancy (HCC, malignant neoplasm of gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts, malignant neoplasm of small intestine including the duodenum and malignant neoplasm of the pancreas).

Statistical Analysis

The categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages and analyzed by using Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact 2-tailed tests. The continuous data were presented as means±standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using the t-test, where appropriate.

For accurate assessment of the competing risks on the impact of PLA, we applied a cause-specific approach of the Cox proportional hazard model to estimate the relative hazard ratio of outcome events between comparison groups. The regression model was made after adjustment of host factors, clinical conditions, and medication usage. Kaplan-Meier method with the Log rank test was used to compare cumulative incidence between comparison groups. Two-tailed p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute’s Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Demographic data for the two groups are shown in Table 1. The gender was similar between the two groups. Patients with ES procedure were significantly older than those with other ERCP (64.70±16.28 vs 63.87±15.22, p=0.0051). As for comorbidities, the ES group had higher prevalence of DM (24.82% vs 23.11%, p=0.0352), disorders of lipoid metabolism (16.07% vs 14.13%, p=0.0044), and HCVD (43.96% vs 37.07%, p<0.0001), whereas the other ERCP group had higher rates of liver cirrhosis (6.21% vs 4.12%, p<0.0001). As for baseline medications, the ES group had significantly higher prescription of NSAID/COX-2 inhibitors (46.44% vs 38.01%, p<0.0001), aspirin (10.87% vs 8.55%, p<0.0001), clopidogrel (3.68% vs 2.99%, p=0.0426), beta blocking agents (11.03% vs 9.59%, p=0.0136), calcium channel blockers (15.19% vs 12.8%, p=0.0003), and statin (9.58% vs 8.16%, p=0.0088) than those of the other ERCP group.

|

Table 1 Patient’s Characteristics Prior to the Index Hospitalization between the Two Groups |

Outcomes

The outcomes are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference with respect to the occurrence of liver abscess (ES [143, 2.01%] versus other ERCP [77, 1.68%], p=0.1970) between the two groups in the 18 years follow-up. There was no significant difference between the two groups about complications of liver abscess including bacterial meningitis and lung abscess.

|

Table 2 Outcomes |

Notably, the ES group had significantly lower incidence of acute pancreatitis (3.80% vs 5.56%, p<0.0001), cholangitis (18.14% vs 21.26%, p<0.0001), and recurrent CBD stones <180 days (12.60% vs 15.05%, p=0.0002) than those of the other ERCP group. The in-hospital mortality rate was similar between the two groups. Interestingly, we also sought the results of microbial cultures from blood or pus. The predominant pathogens were Klebsiella pneumoniae (ES [26.3%] vs other ERCP [17.8%]) and Escherichia coli (ES [19.8%] vs other ERCP [20.7%]).

Validation Analysis

After enrollment, a total of 220 patients were diagnosed as liver abscess. We then decrypted to connect the electronic medical records. After further chart reviewing, 100% (220/220) of them had the right diagnosis of liver abscess and received ERCP exams. We randomly selected the non-liver abscess ICD code in the same period of hospitalization of study groups, and there were negative diagnoses of liver abscess in these 220 cases.

Independent Association Factors of Development of Liver Abscess During Follow-Up Period

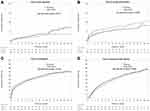

As shown in Figure 2A, patients receiving ES procedure had significantly higher cumulative incidence of liver abscess than that of other ERCP groups during the first 15-year follow-up (5-year cumulative incidence 2.4% vs 1.7%; 10-year cumulative incidence 3.9% vs 3.2%; 15-year cumulative incidence 7.0% vs 3.8%, log-rank p=0.0177) after competing risk analysis.

|

Figure 2 Cumulative incidence between groups: (A) liver abscess; (B) acute pancreatitis; (C) cholangitis; (D) recurrent CBD stones ≥ 180 days. |

The result of association factors for liver abscess is shown in Table 3, patients who underwent ES procedure were at higher risk of liver abscess than those of the other ERCP group (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]=1.49; 95% CI=1.12–1.98, p=0.0058). Female gender (aHR=0.74; 95% CI=0.57–0.97, p=0.0298) was a protective factor against liver abscess. Besides, aging (aHR=1.02; 95% CI= 1.00–1.03, p=0.0048), endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) procedure (aHR=1.66; 95% CI=1.08–2.54, p=0.0196), surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system (aHR=1.60; 95% CI=1.13–2.28, p=0.0080), and development of hepatobiliary malignancy (aHR=2.91; 95% CI=2.07–4.08, p<0.0001) were significant association factors for development of liver abscess.

|

Table 3 Factors Associated with Liver Abscess |

Independent Association Factors of Occurrence of Acute Pancreatitis, Cholangitis, or Recurrent Bile Duct Stones ≥180 Days during Follow-Up Period

There was a significantly lower incidence of acute pancreatitis observed in the ES group with ES procedure than that of the other ERCP group (Figure 2B, log-rank p=0.0002). As shown in Table 4, patients receiving ES procedure had lower risk of acute pancreatitis than that of the other ERCP group (aHR=0.72, 95% CI=0.60–0.85, p=0.0002). Aging (aHR=0.99; 95% CI: 0.99–1.00, p=0.0111) was a protective factor against acute pancreatitis. There was no significant difference with respect to underlying comorbidities between the two groups.

|

Table 4 Factors Associated with Acute Pancreatitis |

There was significantly lower incidence of cholangitis observed in the ES group than in the other ERCP group (Figure 2C, log-rank p=0.0102). On multivariate analysis, as shown in Table 5, patients receiving ES procedure (aHR=0.91, 95% CI=0.84–0.99, p=0.0259) and female gender (aHR=0.82, 95% CI=0.75–0.89, p<0.0001) were protective factors against cholangitis. Aging (aHR=1.01 95% CI=1.00–1.01, p=0.0001) was an association factor for occurrence of cholangitis. Patients with liver cirrhosis (aHR=1.34; 95% CI=1.13–1.58, p=0.0007) and DM (aHR=1.14, 95% CI= 1.02–1.26, p=0.0172) were at higher association rate for cholangitis. The prescription of systemic steroids (aHR=1.36; 95% CI=1.12–1.64, p=0.0016) and ursodeoxycholic acid (aHR=1.27; 95% CI=1.08–1.49, p=0.0036) were association factors for cholangitis.

|

Table 5 Factors Associated with Cholangitis |

The result of association factors for occurrence of recurrent CBD stones is shown in Table 6 and Figure 2D. Aging (aHR=1.02; 95% CI=1.01–1.02, p<0.0001), liver cirrhosis (aHR=1.33, 95% CI= 1.10–1.62, p=0.0033), chronic kidney disease (aHR=1.18; 95% CI=1.02–1.37, p=0.0256) and the prescription of ursodeoxycholic acid (aHR=1.32; 95% CI=1.09–1.58, p=0.0037) were association factors for recurrence of CBD stone ≥180 days after index ERCP treatment.

|

Table 6 Factors Associated with Recurrent Bile Duct Stones ≥180 Days |

Discussions

Previously, the issue about late complication after ES focused on cholangitis, recurrent bile duct stone, cholecystitis, and cholangiocarcinoma.8,16–18 After ES, the barrier between hepatobiliary system and duodenum was broken, and hence promoted duodenal-biliary reflux.13,14,19 The following reflux of enteric fluid inside the bile duct might facilitate bacterial colonization, cholangitis, or even liver abscess. The risk of liver abscess after ES should also be considered but lacks attention. Besides, the risk of PLA after ES was demonstrated than that of other ERCP group (aHR=1.49; 95% CI=1.12–1.98, p=0.0058). The risk was even increased during the follow-up period (5-year cumulative incidence: 2.4%, and 10-year cumulative incidence: 3.9%; 15-year cumulative incidence: 7.0% vs 3.8%). Besides, aging, male gender, surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system and development of hepatobiliary malignancy were significant association factors of PLA. There were few cases reporting the development of liver abscess after ES before. Tanaka et al mentioned five of 419 patients who underwent ES developed PLA with an average follow-up period of more than 10 years.17 Yasuda et al18 reported that two of 144 patients after ES had PLA during the follow-up period. Recently, Peng et al20 conducted a population-based cohort study from the National Health Institute Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan and reported higher risk of PLA among patients receiving ES compared to the general population after 1:1 propensity score matching (4.20 vs 0.94, respectively, per 1,000 person-year). Although the sample size was big, the lack of detail analysis weakened the power of the result. In this current study, we performed a strict selection of cohort and analyzed the data under the consideration of covariate factors including medications and comorbidities. Also, we included the covariate factors such as ERBD, EPBD, surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system, cholecystectomy and development of hepatobiliary malignancy during the follow-up period, which would highly influence the risk of PLA. More importantly, we made a validation analysis to ensure the enrolled cohort was correct. This emphasized the result that ES was an independent risk factor associated with PLA after competing risk analysis. We should carefully monitor the risk of PLA among patients receiving ES.

Apart from this, we found that the risk of acute pancreatitis was significantly lower among patients receiving ES than that of the other ERCP group (aHR=0.72; 95% CI=0.60–0.85, p=0.0002). We assumed the reason was related to the facilitation of small recurrent common bile duct stones clearance after ES for cutting the ampullary sphincter and bile duct sphincter. The bottom line is that the risk of biliary pancreatitis is decreased. Current practice guidelines also recommend ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy as an alternative method if cholecystectomy is not feasible for prevention of recurrent gallstone pancreatitis.21 As for recurrent choledocholithiasis, we defined its occurrence at least more than 6 months after the index ERCP.20 Although not statistically significant on multivariate analysis, a trend toward higher risk of recurrent CBD stones was observed in the ES group (log-rank, p=0.0549, Figure 2D). Aging and liver cirrhosis, with their resultant delayed biliary emptying and bile stasis were independent association factors for recurrent choledocholithiasis in this study, which was correlated with previous studies.13,19 As for cholangitis, liver cirrhosis, DM and aging were association factors in this study. An interesting finding was that the risk of cholangitis was significantly lower in the ES group. Recurrent cholangitis in the absence of retained stones after ES is difficultly defined and the incidence was low in previous studies.22–24 As shown in Figure 2C and D, the cumulative incidence between cholangitis and recurrent CBD stones were similar (up to 30% at 10-year follow-up period), which means that the cholangitis was related to retained or recurrent CBD stones after the ERCP procedure. The bottom is that the ES might facilitate clearance of recurrent CBD stones and therefore decrease the incidence of cholangitis.

There were some limitations in this study. First, although the laboratory data was available in CGRD, however, the lack of complete laboratory data did not allow us to perform more detailed regression analysis. Since the issue about PLA after ES is late complication and the risk increase by years, it’s reasonable to think there is less impact of index laboratory data on the occurrence of PLA after ES. Second, the factors influencing the bile flow such as peri-ampullary diverticulum, biliary stricture, and the size of CBD dilatation were not available in CGRD. Further study should be clarified for identification of their impact on the occurrence of PLA after ES.

In conclusion, this current study showed a significant risk of PLA after patients receiving ES compared with the other ERCP group. We should also carefully monitor the association factors of PLA after ERCP treatment of choledocholithiasis including aging, male gender, surgery for hepato-pancreato-biliary system, and development of hepatobiliary malignancy.

Data Sharing Statement

No data will be shared except besides what is included in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Taoyuan in Taiwan (permitted number 201900919B0C601). This study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed consentfor this study, and the data were analyzed anonymously. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Miss Yi-Hsuan Tsai in the Division of Gastroenterology, Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for the assistance with programming and analyses. The authors would like to thank the Health Information and Epidemiology Laboratory of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chia-Yi Branch.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was funded by the Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CFRPG8J0081) in Taiwan.

Disclosure

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Williams E, Beckingham I, Sayed GE, et al. Updated guideline on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2017;66(5):765–782. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312317

2. Manes G, Paspatis G, Aabakken L, et al. Endoscopic management of common bile duct stones: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51(5):472–491. doi:10.1055/a-0862-0346

3. Köksal AS, Eminler AT, Parlak E. Biliary endoscopic sphincterotomy: techniques and complications. World J Clin Cases. 2018;6(16):1073–1086. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1073

4. Feng Y, Zhu H, Chen X, et al. Comparison of endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for retrieval of choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(6):655–663. doi:10.1007/s00535-012-0528-9

5. Jin PP, Cheng JF, Liu D, et al. Endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation vs endoscopic sphincterotomy for retrieval of common bile duct stones: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(18):5548–5556. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5548

6. Ryozawa S, Itoi T, Katanuma A, et al. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for endoscopic sphincterotomy. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:149–173. doi:10.1111/den.13001

7. Pereira Lima JC, Arciniegas Sanmartin ID, Latrônico Palma B, et al. Risk factors for success, complications, and death after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: a 17-year experience with 2137 cases. Dig Dis. 2020;38:534–541. doi:10.1159/000507321

8. Oliveira-Cunha M, Dennison AR, Garcea G. Late complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016;26(1):1–5. doi:10.1097/SLE.0000000000000226

9. Rahimian J, Wilson T, Oram V, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1654–1659. doi:10.1086/425616

10. Thomsen RW, Jepsen P, Sorensen HT. Diabetes mellitus and pyogenic liver abscess: risk and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1194–1201. doi:10.1086/513201

11. Tsai FC, Huang YT, Chang LY, et al. Pyogenic liver abscess as endemic disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(10):1592–1600. doi:10.3201/eid1410.071254

12. Heneghan HM, Healy NA, Martin ST, et al. Modern management of pyogenic hepatic abscess: a case series and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:80–88. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-4-80

13. Tsai TJ, Lai KH, Lin CK, et al. Role of endoscopic papillary balloon dilation in patients with recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:56–61. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2014.08.004

14. Itokawa F, Itoi T, Sofuni A, et al. Mid-term outcome of endoscopic sphincterotomy combined with large balloon dilation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:223–229. doi:10.1111/jgh.12675

15. Tsai MS, Lin MH, Lee CP, et al. Chang Gung Research Database: a multi-institutional database consisting of original medical records. Biomed J. 2017;40(5):263–269. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2017.08.002

16. Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Follow-up of more than 10 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in young patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85(7):917–921. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00750.x

17. Tanaka M, Takahata S, Konomi H, et al. Long-term consequence of endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(5):465–469. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(98)70086-0

18. Yasuda I, Fujita N, Maguchi H, et al. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy versus endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(6):1185–1191. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.006

19. Kim KY, Han J, Kim HG, et al. Late complications and stone recurrence rates after bile duct stone removal by endoscopic sphincterotomy and large balloon dilation are similar to those after endoscopic sphincterotomy alone. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:637–642. doi:10.5946/ce.2013.46.6.637

20. Peng YC, Lin CL, Sung FC. Risk of pyogenic liver abscess and endoscopic sphincterotomy: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e018818. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018818

21. Liao WC, Tc T, Lee KC, et al. Taiwanese consensus recommendations for acute pancreatitis. J Formosan Med Assoc. 2020;119(9):1343–1352. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2019.07.019

22. Escourrou J, Cordova JA, Lazorthes F, et al. Early and late complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy for biliary lithiasis with and without the gall bladder ‘in situ’. Gut. 1984;25(6):598–602. doi:10.1136/gut.25.6.598

23. Prat F, Malak NA, Pelletier G, et al. Biliary symptoms and complications more than 8 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(3):894–899. doi:10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608900

24. Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Association factors predictive of late complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: long-term (more than 10 years) follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(11):2763–2767. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07019.x

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.