Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 10

Epidemiology and management of chronic constipation in elderly patients

Received 30 December 2014

Accepted for publication 2 March 2015

Published 2 June 2015 Volume 2015:10 Pages 919—930

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S54304

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Walker

Maria Vazquez Roque, Ernest P Bouras

Gastroenterology and Hepatology Department, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA

Abstract: Constipation is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder, with prevalence in the general population of approximately 20%. In the elderly population the incidence of constipation is higher compared to the younger population, with elderly females suffering more often from severe constipation. Treatment options for chronic constipation (CC) include stool softeners, fiber supplements, osmotic and stimulant laxatives, and the secretagogues lubiprostone and linaclotide. Understanding the underlying etiology of CC is necessary to determine the most appropriate therapeutic option. Therefore, it is important to distinguish from pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), slow and normal transit constipation. Evaluation of a patient with CC includes basic blood work, rectal examination, and appropriate testing to evaluate for PFD and slow transit constipation when indicated. Pelvic floor rehabilitation or biofeedback is the treatment of choice for PFD, and its efficacy has been proven in clinical trials. Surgery is rarely indicated in CC and can only be considered in cases of slow transit constipation when PFD has been properly excluded. Other treatment options such as sacral nerve stimulation seem to be helpful in patients with urinary dysfunction. Botulinum toxin injection for PFD cannot be recommended at this time with the available evidence. CC in the elderly is common, and it has a significant impact on quality of life and the use of health care resources. In the elderly, it is imperative to identify the etiology of CC, and treatment should be based on the patient’s overall clinical status and capabilities.

Keywords: pelvic floor dysfunction, constipation, elderly

Introduction

Constipation is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder. The prevalence of constipation in the general population is approximately 20% although it can range anywhere from 2% to 27%, depending on the definition used and population studied.1,2 A population-based study reported that the cumulative incidence of chronic constipation (CC) is higher in the elderly (~20%) compared to a younger population.3 Severe constipation is more common in elderly women, with rates of constipation two to three times higher than that of their male counterparts.3–5 The Rome III criteria use a combination of objective (stool frequency, manual maneuvers needed for defecation) and subjective (straining, lumpy or hard stools, incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction) symptoms to define constipation.6

Treatments for CC have varying degrees of efficacy. Available therapeutic options include stool softeners, fiber supplements, osmotic and stimulant laxatives, and the secretagogues lubiprostone and linaclotide. Epidemiologic studies demonstrate a higher prevalence laxative use in the elderly,3,7–10 and elderly patients residing in nursing homes have a greater prevalence of constipation (up to 50%), with up to 74% of them using daily laxatives.4,10,11

The economic impact of CC in the US is significant, with an estimated 2.5 million physician visits and 100,000 hospitalizations annually.12 Chronic constipation also negatively impacts health related quality of life, with psychological and social consequences.13,14 Therefore, it is important to understand the etiology and management of constipation in this population. This review will also discuss pelvic floor disorders, slow transit constipation, their clinical presentations, and treatment options.

Pelvic floor function

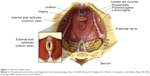

Disorders of the pelvic floor manifesting with both constipation and disorders of incontinence are prevalent in the elderly population. The pelvic floor comprises a group of muscles that have a crucial role in the process of defecation. Understanding the anatomy of the pelvic floor is essential to recognize its role in constipation. The functional anatomy of the pelvic floor consists of the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani and coccygeus muscles) and anal sphincters (external and internal), innervated by the sacral nerve roots (S2–4) and the pudendal nerve (Figure 1). Normal functioning of this neuromuscular unit allows for efficient and complete elimination of stool from the rectum.

| Figure 1 Anatomy of pelvic floor. |

Although studies of constipation in tertiary care centers have described a prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) of 50% or more,15,16 the prevalence of PFD in constipation in the elderly is not well known. PFD is frequently seen in elderly women, particularly those with history of anorectal or pelvic surgery and other pelvic floor trauma such as childbirth.17–20 PFD is not limited to defecation disorders but also can present with urinary tract disorders and sexual dysfunction. As it relates to constipation, PFD may be more appropriately termed a functional defecation disorder, which can be characterized by 1) paradoxical contractions or inadequate relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles, or 2) inadequate propulsive forces during attempted defecation.20 Figure 1 shows the anatomy of the pelvic floor (courtesy of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; permission requested).

Pathophysiology

The two major etiologies of constipation are PFD and slow colonic transit. Patients in whom no cause is identified can be defined as having normal transit constipation. Psychosocial and behavioral issues are also important in the development of constipation. These issues need to be taken into consideration in the elderly, as some may have additional mechanisms that will impact bowel function.

Aging process and the enteric nervous system

The elderly population is impacted by age-related cellular dysfunction that affects plasticity, compliance, altered macroscopic structural changes (ie, diverticulosis), and altered control of the pelvic floor. These molecular and physiologic changes are thought to be involved in the constipation disorders seen in the elderly, and some have been described.18

Studies have demonstrated altered colonic motility mediated by age-related neuronal loss and increased number of altered and dysfunctional myenteric ganglia.20,21 In addition, studies using surgical samples from the descending colon have shown an age-related decrease in inhibitory junction potentials, suggesting a decrease in inhibitory nerves in the smooth muscle membrane.22 A study by Bernard et al demonstrated the selective age-related loss of neurons that express choline acetyltransferase that was accompanied by sparing of nitric oxide-expressing neurons in the human colon.23 Furthermore, a study has reported higher sensory thresholds to rectal distention suggesting altered rectal sensitivity in the elderly.24 The factors that contribute to alteration in motility during aging are complex, with different effects in different regions of the gut.25 Additional proposed physiologic changes in bowel function in the elderly are summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1 Proposed physiologic colonic changes in the elderly |

Pelvic floor dysfunction

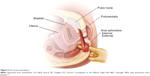

Defecation occurs through a neurologically mediated series of coordinated muscle movements of the pelvic floor and anal sphincters (Figure 2). This process is complex, and dysfunction can lead to abnormal stool expulsion or obstructive defecation.30,31 Abnormalities in this process include failed relaxation of the pelvic floor, paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor muscles, or the inability to produce the necessary propulsive forces needed in the rectum to expel the stool completely. Earlier studies of the pelvic floor in the elderly using anorectal manometry (ARM) did not show differences in anorectal function between the elderly and younger counterparts.32,33 However, other physiologic studies show various abnormalities with aging, such as decreased rectal compliance, increased urge thresholds for defecation, and decreased rest and squeeze pressures in the anal canal.17–19,34,35

| Figure 2 Dynamics of defecation. |

In addition, specific anatomic abnormalities such as rectoceles, sigmoidoceles, and rectoanal intussusception, among others commonly seen in elderly women, also impact the defecation process. Understanding the role and function of the pelvic floor in the development of constipation and its impact in the elderly population is essential for the care of the geriatric population.

Figure 2 illustrates the dynamics of defecation. At rest (left panel), the puborectalis sling holds the rectum at an angle and the anal sphincters are closed. On normal defecation (right panel), 1) the puborectalis relaxes, 2) the anorectal angle straightens, 3) the pelvic floor descends, and 4) the anal sphincter relaxes, allowing stool expulsion when accompanied by adequate propulsive force (courtesy of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; permission requested).

Colonic transit

Delayed colonic transit has been described as a cause of constipation in the elderly. There has been some controversy on the effect of aging on colonic transit. Research studies have described delayed colonic transit in the elderly,36–38 whereas others have described no significant difference in colonic transit between the elderly and younger patients.39,40 However, although decreased propulsive forces of the colon have been described in the elderly,41 there are numerous secondary causes of delayed colonic transit that are commonly seen in the elderly (Table 2). Delayed colonic transit is more often secondary to modifiable causes such as medication side effects (ie, narcotic and/or anticholinergics) and PFD that results in secondary delay of colonic transit by inhibitory reflexes.42,43

| Table 2 Common associations with constipation in the elderly |

Psychosocial and behavioral factors

Constipation is associated with significant psychological impairment.44–46 The elderly population is at risk of significant psychological and social distress since they suffer from greater decreased mobility, altered dietary intake, dependency on others, and issues that may develop from social isolation. Defecation disorders interfere with quality of life and may alter interpersonal, intimate, and interfamily relationships.47–49

Furthermore, the elderly may have decreased awareness to the desire to defecate that can lead to CC with fecal retention. Subsequently, only large stool volumes may be perceived and lead to difficulty with rectal evacuation.50 Awareness of these psychological and behavioral factors are important, and early identification and intervention are helpful in this vulnerable population.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of a patient suffering from constipation is heterogenous. Patients may not always present with the expected decreased bowel frequency and altered consistency but can also present with almost daily bowel movements that require excessive straining, rectal or vaginal digitation to facilitate stool expulsion accompanied with the sensation of incomplete evacuation. The latter are features suggestive of PFD that can also have associated urinary symptoms, such as urine retention and sexual dysfunction, such as dyspareunia.49,51

The clinical presentation of constipation in the elderly appears to be different from other populations. The elderly report more frequent straining, rectal or vaginal digitation, and the sensation of rectal blockage.4,52,53 In addition, many constipated elderly patients experience fecal seepage and are frequently misdiagnosed with fecal incontinence.54 In this setting, patients often have a history of constipation with the sensation of incomplete rectal evacuation, with frequent and incomplete bowel movements and excessive wiping. Often, these patients are prescribed antidiarrheals for presumed incontinence, which worsen the situation with fecal impaction and overflow incontinence secondary to obstruction to defecation. In addition, fecal impaction can cause stercoral ulcers and rectal bleeding. A thorough history and examination, which needs to include a complete rectal examination, are essential.

Severe constipation can lead to secondary alterations in GI motility, resulting in upper GI symptoms. Patients with CC have been shown to have delayed gastric emptying, right colon transit, and prolonged mouth-to-cecum transit time.2 Patients with CC often present with concomitant dyspepsia, abdominal cramping, bloating, flatulence, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting.5,46,55–57

Details of the medical history should include the use of constipating medications, physical or mental health decline, coexisting medical conditions, dietary habits, and general psychosocial situation. Use of chronic narcotics should also be addressed, especially in patients with chronic pain. A personal or family history of colon cancer should be ascertained as well as a prior colonoscopy.

Diagnostic approach

Patients typically present to their primary care physician for the initial evaluation and management of constipation. Initially, it is important to determine the patient’s understanding of constipation. Standard diagnostic studies typically include baseline blood work to exclude any significant metabolic and structural tests to evaluate for anatomic abnormalities. Patients with persistent constipation, normal investigations, and a failed response to initial empiric therapies are the ones typically referred to the gastroenterologist. Pursuing relevant studies that help categorize patients as to the cause of their constipation facilitates selection of the appropriate therapy for each specific physiologic subgroup.2,51

History and physical examination

A comprehensive history focusing on relevant clinical features, including a thorough medication review is needed. The physical examination is not complete without a thorough perianal and digital rectal examination. This portion of the exam not only assess for mass lesions, anal strictures, fissures, or stool impaction but on the mechanics of defecation.58,59

Figure 3 depicts the anorectal examination (courtesy of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; permission requested). With the patient in the left lateral position, the examiner should assess 1) resting sphincter tone and presence of spasm, 2) sensation, including the presence of pain, 3) the ability to squeeze, and 4) coordination of the pelvic floor and rectal muscles and extent of perineal descent during simulated defecatory straining (expelling the examiner’s finger).

| Figure 3 Anorectal examination. |

Metabolic and structural evaluation

Although important, particularly for individuals on multiple medications with various comorbid conditions, routine lab tests such as a complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium levels, and thyroid function studies rarely identify the cause of CC. Further, the yield of colonoscopy and barium enema in patients with constipation is the same as the general population.60,61 These diagnostic studies are indicated in patients with alarm symptoms such as hematochezia or weight loss and for the acute onset of constipation in the elderly. Routine colon cancer screening is recommended for all patients 50 years or older. Plain abdominal radiographs are helpful to assess fecal load, impaction, or obstruction.

Pelvic floor evaluation

Assessment of the pelvic floor function is essential to determine if PFD is the underlying cause of constipation. Patients who have failed initial laxative therapy or who have symptoms suggestive of PFD should undergo formal testing. However, the reliability and comparability of many tests are unknown. Current available tests include ARM, standard defecography, and dynamic magnetic resonance imaging defecography. ARM has the ability to assess tone, strength, sensation, control, and coordination with defecatory straining. ARM with balloon expulsion testing provides measurements that relay key information about the motor and sensory control of the anorectum and pelvic floor.62–64 Failed balloon expulsion, abnormal sensory thresholds, hypertensive sphincters, and dyssynergic pattern during attempted defecation are all findings seen in ARM testing that support the diagnosis of PFD. Defecography can identify the presence of anatomic abnormalities that will impact rectal evacuation.65 Significant anatomical abnormalities of the pelvic floor (ie, pelvic organ prolapse, rectocele, among others) and inability to evacuate the rectal gel are some features seen in defecography that are suggestive of PFD. There is no single gold standard test to confidently diagnose PFD, and more than one test is required for the proper diagnosis. In certain cases, assessment by a trained physical therapist in pelvic floor retraining is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of PFD. Table 3 summarizes clinical presentation and common diagnostic findings in patients with PFD.

| Table 3 Diagnostic findings in patients with defecatory disorders |

Colonic transit

Colon transit studies objectively determine the rate of stool movement through the colon, although clinically it is rarely indicated. Currently available colon transit studies include the radiopaque markers (ROM), colonic scintigraphy, and the wireless motility capsule (WMC). ROM studies are inexpensive and are a widely available way to assess colon transit.66,67 In addition to total marker counts, marker distribution may also be helpful, as proximal retention suggests colonic dysfunction, whereas the retention of markers exclusively in the lower left colon is more suggestive of PFD. Scintigraphic techniques allow for shorter studies (24–48 hours) and decreased radiation exposure.68,69 The WMC or SmartPill® has sensors that measures pH, pressure, and temperature, which collectively determine regional and whole gut transit times of the GI tract.70 A recent study compared the WMC with ROM in 39 constipated and eleven healthy older subjects (≥65 years). The device agreement for slow colonic transit was 88%, with good correlation between WMC and ROM in elderly patients, suggesting that the WMC was a useful diagnostic device of delayed colonic transit in elderly constipated patients.71

Factors that will impact GI transit include PFD, medications, diet, and the presence of excessive stool or impaction.

Treatment

Selection of treatment in CC depends on the underlying physiologic cause. In the elderly population it is important to consider other factors that impact constipation such as dehydration, dementia among others prior to initiating a specific therapy (Table 4).72 Table 5 briefly summarizes commonly used agents to treat constipation and their mechanisms of action. Generally, fiber supplementation is a reasonable initial therapeutic approach; however, patients that do not respond to fiber supplementation can be advanced to osmotic laxatives. The latter should be titrated to clinical response. Stimulant laxatives and prokinetic agents should be reserved for patients who are refractory to fiber supplements or osmotic laxatives. Surgery is rarely indicated for constipation, exclusion of PFD is essential, and surgical outcomes in the elderly are uncertain. Fecal impaction should be cleared before instituting maintenance regimens. Treatment for CC also needs to be tailored to the patient’s medical history, medications, overall clinical status, mental and physical abilities, tolerance to various agents, and realistic treatment prospects. Patients that are institutionalized need to be addressed with standardized and supervised bowel programs.

| Table 4 Clinical factors that impact bowel function in the elderly |

| Table 5 Summary of commonly used laxative agents |

Bulking agents

Fiber supplementation is a reasonable first step in the management of CC. Soluble, but not insoluble, fiber agents facilitate bowel function by increasing water absorbency capacity of stool resulting in improved stool frequency and consistency.73 Trials looking at bulking agents are of suboptimal design, and most are plagued by small sample sizes and short study duration.74 Common reported side effects include bloating, gas, and distention, but these symptoms often decrease with time. Synthetic supplements are often better tolerated. Patients with slow transit constipation or PFD will likely not benefit from fiber supplementation.

Although increasing water intake alone has not been shown to improve constipation, maintaining adequate fluid intake is important with fiber supplementation to avoid excessive bulk, which may exacerbate CC. Fluid intake needs to be monitored in patients with cardiac or renal disease, and the need to maintain adequate hydration may be a limitation for some.

Laxatives

Available laxatives in the marketplace include osmotic and stimulant laxatives (Table 5). Osmotic laxatives are a reasonable choice for patients not responding to fiber supplementation. Laxative selection should be based on relevant medical history such as cardiac or renal status, possible drug interactions, cost, and side effects. There is no clear superior osmotic agent; therefore, the dose should be titrated to the clinical response.

For chronic or more severe constipation, regular dosing is indicated. Per US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prescribing information, high doses of polyethylene glycol may produce excessive stool frequency, especially in elderly nursing home residents, and nausea, abdominal bloating, cramping, and flatulence may occur.74–76 Stimulant laxatives, which promote intestinal motility through high-amplitude contractions, do not seem to lead to bowel injury contrary to prior belief.77,78 However, these drugs are better reserved for those with a failed response to osmotic agents and may be required in the management of opioid-induced constipation. Effective for many patients, studies with laxatives in the elderly are limited and are of suboptimal design.79 Abdominal discomfort, electrolyte imbalances, allergic reactions, and hepatotoxicity have been reported.80 There needs to be caution with the use of magnesium-based laxatives in patients with renal disease as there are a few case reports of severe hypermagnesemia.80

Stool softeners, suppositories, and enemas

Stool softeners, which enhances softer stool consistency, are overall of limited efficacy.81,82 Suppositories (ie, glycerin and bisacodyl) help initiate or facilitate rectal evacuation. They may be used alone, but preferentially in conjunction with meals to capture the gastrocolic reflex or in conjunction with other agents.83 Suppositories, which usually work within minutes, may be tried as part of a behavioral program for those with obstructed defecation and in institutionalized patients. Enemas may be used judiciously on an as-needed basis, particularly for obstructed defecation and to avoid fecal impaction. Tap water enemas seem safe for more regular use. Electrolyte imbalances such as hyperphosphatemia are more common with phosphate enemas and regular use is discouraged.84 Soapsuds enemas can cause rectal mucosal damage with colitis and are not routinely recommended.85

Prokinetics

Prokinetic agents exert their action through the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 receptor of the enteric nervous system, stimulating secretion and motility. Cisapride has been removed from the market due to cardiovascular side effects, with fatal cardiac arrhythmias due to its effect in QT interval prolongation.

Tegaserod was effective for CC in men and women younger than 65 years,86,87 but data in the elderly is lacking. Although the drug seems effective in the management of constipation, use has been markedly restricted secondary to the risk of cardiac events with ischemia. Prucalopride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agent similar to tegaserod, accelerates colonic transit in patients with constipation, and therapeutic trials have demonstrated efficacy for severe constipation.88,89 Prucalopride for 4 weeks in elderly nursing home residents was safe and well tolerated, with no adverse cardiac side effects and QT interval prolongation.90 Prucalopride is currently not approved for use in the US by the FDA.

Secretagogues

Lubiprostone is a bicyclic fatty acid that activates type 2 chloride channels on the apical membrane of the enterocytes, which results in the chloride secretion with water and sodium diffusion. Its efficacy has been proved in various clinical trials.91–93 However, its effectiveness is limited by the side effect of nausea in approximately 25%–30% of patients with CC, but nausea may improve if taken with food.93 The indication for lubiprostone in patients with a primary problem of PFD is not established.

Linaclotide, a guanylin and uroguanylin analog, increases intestinal secretion by activation of the guanylate cyclase receptor.94 Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of linaclotide in CC in improving stool consistency, straining, abdominal discomfort, bloating, global assessments, and quality of life.95 The most common reported side effect is diarrhea. Caution should be used with these medications in light of their side-effect profile, cost, and efficacy compared to simple, less expensive alternatives.

Pelvic floor rehabilitation (biofeedback)

Pelvic floor rehabilitation or biofeedback is the treatment of choice for PFD. The goals of therapy include educating patients about PFD, coordinating increased intra-abdominal pressure with pelvic floor muscles relaxation during evacuation, and practicing simulated defecation with a balloon.96 In some specialized centers, sensory retraining of the rectum can be done to restore rectal sensation, especially in the cases of rectal hyposensitivity. There are no obvious adverse effects of treatment. Uncontrolled studies suggest that biofeedback is effective in more than 70% of patients, and these findings have been confirmed in several randomized, controlled trials.97–100 Biofeedback has been shown to be superior to laxatives in patients with PFD, and the effect was durable.98 The key is identifying the problem and available therapeutic resources. A randomized trial of biofeedback for PFD in the elderly showed improvement in physiologic measures and in bowel function after eight sessions in 1 month.101 In addition, psychiatric comorbidities need to be addressed early and treated prior or concomitantly with therapy as data suggests that it may play a significant role.48 Concomitant slow colon transit frequently requires simultaneous treatment and can improve once the PFD has been rehabilitated.

Surgery

Rarely indicated, subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is the treatment of choice for refractory slow transit constipation in cases when PFD is excluded.102,103 Outcomes in the elderly are uncertain. Complications include diarrhea, incontinence, and bowel obstruction.104 Extra caution should be used in patients with abdominal pain, which tend to respond poorly, and this needs to be explained prior to surgery. Results of segmental colonic resections for constipation are disappointing compared to ileorectal anastomosis.105

Surgical indications for PFD are poorly defined, and surgery should be considered only if functional significance can be determined.103,105 The stapled transanal resection was intended to repair rectal intussusception and rectoceles by removing redundant mucosa. However, these anatomical abnormalities have been widely thought to be secondary to PFD since the relationship of these findings and CC symptoms is weak. Moreover, long-term outcomes of patients that seemed to be adequate candidates for the stapled transanal resection procedure have not been promising.2 Division of the puborectalis is not recommended.106 Overall, treatment of the underlying PFD first is a reasonable treatment approach, with surgery reserved for those not responding to more conservative therapy.

Other therapies

Alternative therapies to manage CC included sacral nerve stimulation and botulinum toxin injection therapy for PFD. Sacral nerve stimulation has been shown to be helpful in some small trials107 and may be useful for patients with combined urinary dysfunction. Botulinum toxin therapy cannot be recommended based on the available data.108,109

Additional comments

Adjunctive therapy may be necessary for psychopathology associated with CC, and maintaining adequate caloric intake is essential. Evidence does not support the popular notion that toxins from constipation harm the body or that irrigation is needed.

There is no obvious significance of an elongated colon (dolichocolon), and surgical shortening does not lead to reliable clinical improvement.78 Likewise, physical activity and water intake are controversial subjects, with unclear associations with colon transit and constipation.78 There is no value in over hydrating a patient; families, long-term care facilities, and physicians should just guard against dehydration. Although mineral oil, colchicine,110 and misoprostol111,112 may improve constipation, these agents have potential side effects and complications that likely outweigh any potential benefits. Their use in the elderly has not been explored and not recommended. Alteration of the bacterial milieu in the colon has been associated with slow transit constipation.113,114

Summary

CC in the elderly is common, and it has a significant impact on quality of life and the use of health care resources. A careful history, medication assessment, and physical examination are helpful in obtaining relevant clues that aid direct management. Physiologic categorization of the cause leading to patient presentation improves management outcomes, and it is important to consider that many causes can be present in one patient, and many factors influence the clinical presentation of an older patient. Fiber supplementation and osmotic laxatives are an effective first line of therapy for many patients. A consistent history or inadequate response to standard initial therapy should prompt an assessment for PFD. If identified, and the patient is a reasonable treatment candidate, pelvic floor rehabilitation (biofeedback) is the treatment of choice. Surgery is rarely indicated in CC. Special effort should be taken to identify features inherent to the elderly, and treatment should be based on the patient’s overall clinical status and capabilities.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):750–759. | ||

Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(1):218–238. | ||

Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Cumulative incidence of chronic constipation: a population-based study 1988–2003. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(11–12):1521–1528. | ||

Talley NJ, Fleming KC, Evans JM, et al. Constipation in an elderly community: a study of prevalence and potential risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(1):19–25. | ||

Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(7):917–930. | ||

Longstreth GF. Functional bowel disorders: functional constipation. In: Drossman DA, editor. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press; 2006:515–523. | ||

Whitehead WE, Drinkwater D, Cheskin LJ, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Constipation in the elderly living at home. Definition, prevalence, and relationship to lifestyle and health status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(5):423–429. | ||

Donald IP, Smith RG, Cruikshank JG, Elton RA, Stoddart ME. A study of constipation in the elderly living at home. Gerontology. 1985;31(2):112–118. | ||

Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, Bohn R, Minaker KL. Bowel habit in relation to age and gender. Findings from the National Health Interview Survey and clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(3):315–320. | ||

Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, Choodnovskiy I, Minaker KL. Constipation: assessment and management in an institutionalized elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(9):947–952. | ||

Primrose WR, Capewell AE, Simpson GK, Smith RG. Prescribing patterns observed in registered nursing homes and long-stay geriatric wards. Age Ageing. 1987;16(1):25–28. | ||

Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34(4):606–611. | ||

Bongers ME, Benninga MA, Maurice-Stam H, Grootenhuis MA. Health-related quality of life in young adults with symptoms of constipation continuing from childhood into adulthood. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:20. | ||

Wang JP, Duan LP, Ye HJ, Wu ZG, Zou B. [Assessment of psychological status and quality of life in patients with functional constipation]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2008;47(6):460–463. Chinese. | ||

Costilla VC, Foxx-Orenstein AE. Constipation in adults: diagnosis and management. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12(3):310–321. | ||

Costilla VC, Foxx-Orenstein AE. Constipation: understanding mechanisms and management. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(1):107–115. | ||

Bannister JJ, Abouzekry L, Read NW. Effect of aging on anorectal function. Gut. 1987;28(3):353–357. | ||

Camilleri M, Lee JS, Viramontes B, Bharucha AE, Tangalos EG. Insights into the pathophysiology and mechanisms of constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and diverticulosis in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(9):1142–1150. | ||

Laurberg S, Swash M. Effects of aging on the anorectal sphincters and their innervation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(9):737–742. | ||

Yu SW, Rao SS. Anorectal physiology and pathophysiology in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(1):95–106. | ||

Hanani M, Fellig Y, Udassin R, Freund HR. Age-related changes in the morphology of the myenteric plexus of the human colon. Auton Neurosci. 2004;113(1–2):71–78. | ||

Koch TR, Carney JA, Go VL, Szurszewski JH. Inhibitory neuropeptides and intrinsic inhibitory innervation of descending human colon. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36(6):712–718. | ||

Bernard CE, Gibbons SJ, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, et al. Effect of age on the enteric nervous system of the human colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(7):746–e46. | ||

Lagier E, Delvaux M, Vellas B, et al. Influence of age on rectal tone and sensitivity to distension in healthy subjects. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1999;11(2):101–107. | ||

Saffrey MJ. Ageing of the enteric nervous system. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(12):899–906. | ||

Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Gibbons SJ, Sarr MG, et al. Changes in interstitial cells of cajal with age in the human stomach and colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(1):36–44. | ||

Singh J, Kumar S, Krishna CV, Rattan S. Aging-associated oxidative stress leads to decrease in IAS tone via RhoA/ROCK downregulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306(11):G983–G991. | ||

Lewicky-Gaupp C, Hamilton Q, Ashton-Miller J, Huebner M, DeLancey JO, Fenner DE. Anal sphincter structure and function relationships in aging and fecal incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):559.e1–e559.e5. | ||

Gundling F, Seidl H, Scalercio N, Schmidt T, Schepp W, Pehl C. Influence of gender and age on anorectal function: normal values from anorectal manometry in a large caucasian population. Digestion. 2010;81(4):207–213. | ||

Rao SS. Dyssynergic defecation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30(1):97–114. | ||

Schey R, Cromwell J, Rao SS. Medical and surgical management of pelvic floor disorders affecting defecation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1624–1633; quiz p.1634. | ||

Loening-Baucke V, Anuras S. Effects of age and sex on anorectal manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80(1):50–53. | ||

Loening-Baucke V, Anuras S. Anorectal manometry in healthy elderly subjects. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1984;32(9):636–639. | ||

McHugh SM, Diamant NE. Effect of age, gender, and parity on anal canal pressures. Contribution of impaired anal sphincter function to fecal incontinence. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32(7):726–736. | ||

Orr WC, Chen CL. Aging and neural control of the GI tract: IV. Clinical and physiological aspects of gastrointestinal motility and aging. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283(6):G1226–G1231. | ||

Madsen JL, Graff J. Effects of ageing on gastrointestinal motor function. Age Ageing. 2004;33(2):154–159. | ||

Melkersson M, Andersson H, Bosaeus I, Falkheden T. Intestinal transit time in constipated and non-constipated geriatric patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18(5):593–597. | ||

Wiskur B, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. The aging colon: the role of enteric neurodegeneration in constipation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12(6):507–512. | ||

Evans JM, Fleming KC, Talley NJ, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Relation of colonic transit to functional bowel disease in older people: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(1):83–87. | ||

Meier R, Beglinger C, Dederding JP, et al. Influence of age, gender, hormonal status and smoking habits on colonic transit time. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1995;7(4):235–238. | ||

Salles N. Basic mechanisms of the aging gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis. 2007;25(2):112–117. | ||

Nullens S, Nelsen T, Camilleri M, et al. Regional colon transit in patients with dys-synergic defaecation or slow transit in patients with constipation. Gut. 2012;61(8):1132–1139. | ||

Shin A, Camilleri M, Nadeau A, et al. Interpretation of overall colonic transit in defecation disorders in males and females. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):502–508. | ||

Wald A, Hinds JP, Caruana BJ. Psychological and physiological characteristics of patients with severe idiopathic constipation. Gastroenterology. 1989;97(4):932–937. | ||

Merkel IS, Locher J, Burgio K, Towers A, Wald A. Physiologic and psychologic characteristics of an elderly population with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(11):1854–1859. | ||

Towers AL, Burgio KL, Locher JL, Merkel IS, Safaeian M, Wald A. Constipation in the elderly: influence of dietary, psychological, and physiological factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(7):701–706. | ||

Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, Thompson WG, Rance L. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(8):1986–1993. | ||

Nehra V, Bruce BK, Rath-Harvey DM, Pemberton JH, Camilleri M. Psychological disorders in patients with evacuation disorders and constipation in a tertiary practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(7):1755–1758. | ||

Rao SS, Tuteja AK, Vellema T, Kempf J, Stessman M. Dyssynergic defecation: demographics, symptoms, stool patterns, and quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(8):680–685. | ||

Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(3):895–901. | ||

Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(14):1360–1368. | ||

Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, Bohn R, Minaker KL. How do older persons define constipation? Implications for therapeutic management. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(1):63–66. | ||

Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Functional constipation and outlet delay: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(3):781–790. | ||

Rao SS, Ozturk R, Stessman M. Investigation of the pathophysiology of fecal seepage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(11):2204–2209. | ||

Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38(9):1569–1580. | ||

Locke GR 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Fett SL, Melton LJ 3rd, Talley NJ. Overlap of gastrointestinal symptom complexes in a US community. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17(1):29–34. | ||

Kolar GJ, Camilleri M, Burton D, Nadeau A, Zinsmeister AR. Prevalence of colonic motor or evacuation disorders in patients presenting with chronic nausea and vomiting evaluated by a single gastroenterologist in a tertiary referral practice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26(1):131–138. | ||

Talley NJ. How to do and interpret a rectal examination in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(4):820–822. | ||

Tantiphlachiva K, Rao P, Attaluri A, Rao SS. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):955–960. | ||

Patriquin H, Martelli H, Devroede G. Barium enema in chronic constipation: is it meaningful? Gastroenterology. 1978;75(4):619–622. | ||

Pepin C, Ladabaum U. The yield of lower endoscopy in patients with constipation: survey of a university hospital, a public county hospital, and a Veterans Administration medical center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(3):325–332. | ||

Rao SS, Singh S. Clinical utility of colonic and anorectal manometry in chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(9):597–609. | ||

Lee BE, Kim GH. How to perform and interpret balloon expulsion test. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20(3):407–409. | ||

Rao SS, Ozturk R, Laine L. Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(7):1605–1615. | ||

Fletcher JG, Busse RF, Riederer SJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(2):399–411. | ||

Metcalf AM, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR, MacCarty RL, Beart RW, Wolff BG. Simplified assessment of segmental colonic transit. Gastroenterology. 1987;92(1):40–47. | ||

Hinton JM, Lennard-Jones JE, Young AC. A new method for studying gut transit times using radioopaque markers. Gut. 1969;10(10):842–847. | ||

Stivland T, Camilleri M, Vassallo M, et al. Scintigraphic measurement of regional gut transit in idiopathic constipation. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(1):107–115. | ||

Rao SS, Camilleri M, Hasler WL, et al. Evaluation of gastrointestinal transit in clinical practice: position paper of the American and European Neurogastroenterology and Motility Societies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23(1):8–23. | ||

Lee YY, Erdogan A, Rao SS. How to assess regional and whole gut transit time with wireless motility capsule. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20(2):265–270. | ||

Rao SS, Coss-Adame E, Valestin J, Mysore K. Evaluation of constipation in older adults: radioopaque markers (ROMs) versus wireless motility capsule (WMC). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):289–294. | ||

Bouras EP, Tangalos EG. Chronic Constipation in the Elderly. Gastroenterology Clinics. 2009;38(3):463–480. | ||

Suares NC, Ford AC. Systematic review: the effects of fibre in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(8):895–901. | ||

Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, et al; Task Force on the Management of Functional Bowel Disorders. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(Suppl 1):S2–S26; quiz 27. | ||

Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld P, Talley NJ. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S5–S21. | ||

Ford AC, Suares NC. Effect of laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2011;60(2):209–218. | ||

Wald A. Is chronic use of stimulant laxatives harmful to the colon? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36(5):386–389. | ||

Müller-Lissner SA, Kamm MA, Scarpignato C, Wald A. Myths and misconceptions about chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):232–242. | ||

Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(10):2222–2230. | ||

Nyberg C, Hendel J, Nielsen OH. The safety of osmotically acting cathartics in colonic cleansing. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(10):557–564. | ||

Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):936–971. | ||

Castle SC, Cantrell M, Israel DS, Samuelson MJ. Constipation prevention: empiric use of stool softeners questioned. Geriatrics. 1991;46(11):84–86. | ||

Leung FW, Rao SS. Approach to fecal incontinence and constipation in older hospitalized patients. Hosp Pract (1995). 2011;39(1):97–104. | ||

Sédaba B, Azanza JR, Campanero MA, Garcia-Quetglas E, Muñoz MJ, Marco S. Effects of a 250-mL enema containing sodium phosphate on electrolyte concentrations in healthy volunteers: An open-label, randomized, controlled, two-period, crossover clinical trial. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2006;67(5):334–349. | ||

Schmelzer M, Schiller LR, Meyer R, Rugari SM, Case P. Safety and effectiveness of large-volume enema solutions. Appl Nurs Res. 2004;17(4):265–274. | ||

Johanson JF, Wald A, Tougas G, et al. Effect of tegaserod in chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(9):796–805. | ||

Kamm MA, Müller-Lissner S, Talley NJ, et al. Tegaserod for the treatment of chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multinational study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(2):362–372. | ||

Bouras EP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Thomforde G, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR. Prucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorder. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(2):354–360. | ||

Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(22):2344–2354. | ||

Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Safety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21(12):1256–e117. | ||

Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome – results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):329–341. | ||

Johanson JF, Drossman DA, Panas R, Wahle A, Ueno R. Clinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(8):685–696. | ||

Johanson JF, Morton D, Geenen J, Ueno R. Multicenter, 4-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of lubiprostone, a locally-acting type-2 chloride channel activator, in patients with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):170–177. | ||

Bharucha AE, Linden DR. Linaclotide – a secretagogue and antihyperalgesic agent – what next? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(3): 227–231. | ||

Vazquez Roque M, Camilleri M. Linaclotide, a synthetic guanylate cyclase C agonist, for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders associated with constipation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5(3):301–310. | ||

Bharucha AE, Rao SS. An update on anorectal disorders for gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):37–45.e2. | ||

Rao SS, Valestin J, Brown CK, Zimmerman B, Schulze K. Long-term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(4):890–896. | ||

Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, Morelli A, Bassotti G. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):657–664. | ||

Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback, sham feedback, and standard therapy for dyssynergic defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(3):331–338. | ||

Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, Ringel Y, Drossman D, Whitehead WE. Randomized, controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(4):428–441. | ||

Simón MA, Bueno AM. Behavioural treatment of the dyssynergic defecation in chronically constipated elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2009;34(4):273–277. | ||

Hassan I, Pemberton JH, Young-Fadok TM, et al. Ileorectal anastomosis for slow transit constipation: long-term functional and quality of life results. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(10):1330–1336; discussion 1336–1337. | ||

Gladman MA, Knowles CH. Surgical treatment of patients with constipation and fecal incontinence. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37(3):605–625. | ||

Knowles CH, Scott M, Lunniss PJ. Outcome of colectomy for slow transit constipation. Ann Surg. 1999;230(5):627–638. | ||

Rotholtz NA, Wexner SD. Surgical treatment of constipation and fecal incontinence. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001;30(1):131–166. | ||

Kamm MA, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE. Lateral division of the puborectalis muscle in the management of severe constipation. Br J Surg. 1988;75(7):661–663. | ||

Kamm MA, Dudding TC, Melenhorst J, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for intractable constipation. Gut. 2010;59(3):333–340. | ||

Maria G, Cadeddu F, Brandara F, Marniga G, Brisinda G. Experience with type A botulinum toxin for treatment of outlet-type constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(11):2570–2575. | ||

Faried M, El Nakeeb A, Youssef M, Omar W, El Monem HA. Comparative study between surgical and non-surgical treatment of anismus in patients with symptoms of obstructed defecation: a prospective randomized study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(8):1235–1243. | ||

Verne GN, Davis RH, Robinson ME, Gordon JM, Eaker EY, Sninksy CA. Treatment of chronic constipation with colchicine: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(5):1112–1116. | ||

Soffer EE, Metcalf A, Launspach J. Misoprostol is effective treatment for patients with severe chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(5): 929–933. | ||

Roarty TP, Weber F, Soykan I, McCallum RW. Misoprostol in the treatment of chronic refractory constipation: results of a long-term open label trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(6):1059–1066. | ||

Ghoshal UC, Srivastava D, Verma A, Misra A. Slow transit constipation associated with excess methane production and its improvement following rifaximin therapy: a case report. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17(2):185–188. | ||

Attaluri A, Jackson M, Valestin J, Rao SS. Methanogenic flora is associated with altered colonic transit but not stool characteristics in constipation without IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(6):1407–1411. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.