Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 10

Epidemiology and evolution of the diagnostic classification of factitious disorders in DSM-5

Authors Caselli I, Poloni N , Ielmini M, Diurni M, Callegari C

Received 6 October 2017

Accepted for publication 2 November 2017

Published 11 December 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 387—394

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S153377

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Ivano Caselli, Nicola Poloni, Marta Ielmini, Marcello Diurni, Camilla Callegari

Department of Medicine and Surgery, Section of Psychiatry, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy

Abstract: A systematic search for all case reports and case series of adult patients with factitious disorders (FD) in the databases MEDLINE, Scopus, and PsycINFO was conducted. FD is a psychiatric disorder in which sufferers intentionally fabricate physical or psychological symptoms in order to assume the role of a patient, without any obvious gain. The clinical and demographic profile of patients with FD has not been sufficiently clear. Thus, the aims of this study were to outline a demographic and clinical profile of a large sample of patients with FD and to study the evolution of the position of FD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. One thousand six hundred thirty-six records were obtained based on key search terms, after exclusion of duplicate records. Five hundred seventy-seven articles were identified as potentially eligible for the study, of which 314 studies were retrieved for full-text review. These studies included 514 cases. Variables extracted included age, gender, reported occupation, comorbid psychopathology, clinical presentation, and factors leading to the diagnosis of FD. In the sample, 65.4% of patients were females. Mean age at presentation was 33.5 years. A health care profession was reported most frequently (n=113). Patients were most likely to present in psychiatry, neurology, emergency, and internal medicine departments. The broad survey of sociodemographic profile of the sample has highlighted some important points for early diagnosis and early psychiatric treatment. The study showed that the patients did not meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 diagnostic criteria in 11.3% of cases.

Keywords: fabricated illness, factitious disorder, medically unexplained symptoms, Munchausen syndrome

Introduction

Factitious disorder (FD) is a psychiatric disorder in which sufferers intentionally fabricate physical or psychological symptoms in order to assume the role of a patient, without any obvious gain.1 Patients with FD often gain hospital admission and undergo invasive procedures and surgeries exposing themselves to a considerable risk of iatrogenic harm.

Factitious patients are difficult to detect and they have a heavy impact on the health care services and National Health Service. The need for improving and speeding up the diagnostic approach and, consequently, therapeutic treatments is felt.

It is possible to identify some predisposing factors to FD such as other mental disorders, general medical conditions that require treatment and hospitalization, especially in childhood or adolescence, deprivation stories (losses, family breakdowns, etc.), and emotional and physical abuses in childhood.2

The exact prevalence of the disorder is currently unknown but it has been estimated between 0.6% and 3% of referrals from general medicine to psychiatry and between 0.02% and 0.9% of cases reviewed in specialist clinics.3

FD appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Diseases (DSM) from the third edition. According to DSM-III-R (1986), FD should be distinguished from malingering in which fabrication is motivated by an external reward.

In DSM-IV-TR, FD represents an autonomous diagnostic category. Three subtypes of distinct FD are distinguished by predominant symptoms:

- with predominant psychic signs and symptoms;

- with predominant physical signs and symptoms;

- with combined psychic and physical signs and symptoms.

In DSM-5, FD are part of the largest section of Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders. All the disorders discussed in this article have in common the relevance of somatic symptoms associated with significant discomfort and impairment. These diagnostic formulations are more useful to general practitioners and non-psychiatric specialists in the field of general medicine and in other clinical areas where individuals who present disorders with significant somatic symptoms are more common than in mental health care services. The current classification considers the central aspect of the involvement of the body and the broad overlapping to somatoform disorders.

Early detection of FD is very important to limit harm to patients, and early management of FD may facilitate improved outcomes for patients with the disorder.

However, the clinical and demographic profile of patients with FD has not been sufficiently clarified.4,5 Recommendations and guidelines have not been supported by broad evidence on how FD is diagnosed by clinicians or how methods for detecting FD earlier may vary among medical specialties.

Studies on FD demonstrate the huge impact of unnecessary investigations, treatments, and hospital admission on the health care system. Early detection of FD is necessary in order to limit wastage of health care resources and harm to patients.6,7

Articles on FD are mostly case reports and reviews. Only a limited number of studies have been published in the literature and those published to date have been limited to a small number of cases.

Thus, the aim of this study was to draft a comprehensive systematic review of all cases of FD published in the professional literature. It is useful to carry out a literature review to characterize the profile of patients with FD. Purposely, the end points are

- to outline a demographic and clinical profile of a large sample of patients with FD;

- to study the evolution of position of FD in the DSM.

Methods

A systematic review of all case reports and case series of adult patients which fulfilled DSM-5 diagnostic criteria was conducted. The research involved cases diagnosed according to DSM-III, DSM-IV, or ICD-10 criteria. A broad keyword search of the professional literature published in English from January 1950 to November 2016 was conducted. The databases MEDLINE, Scopus, and PsycINFO were searched using the MeSH terms factitious and Munchausen. The terms artefacta, fabricated illness, and medically unexplained symptoms were included. Exclusion criteria were the following:

- Cases by proxy

- Age <18 years old

- Articles not in English

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses) flowchart of the search is shown in Figure 1. A total of 1636 records were returned based on key search terms, after exclusion of duplicate records. Five hundred seventy-seven articles were identified as potentially eligible for the study, of which 314 studies were retrieved for full-text review. These studies included 514 cases. Single cases have been extracted from 74.1% of the studies, whereas 25.9% of the selected articles contained multiple cases.

| Figure 1 PRISMA flow chart. |

The following quantitative and qualitative variables were obtained: age, gender, marital status, race and ethnicity, reported occupation, psychopathology, medical diseases, clinical presentation, multiple surgeries, abuse in childhood, substance abuse, experience of illness or long-lasting hospitalization, traumatic experiences, conflicting relationships, premature familiar bereavements, grudge toward the medical profession, use of paramedical facilities, suicidal behavior, cause of death, and psychiatric counseling.

Factors leading to the diagnosis of FD were extracted using a checklist adapted from two surveys of clinical information that might raise the suspicion of FD.5,8

Starting from the review of Yates and Steel, the following items were considered: past health care service use, atypical presentation, exclusion of organic and/or psychiatric causes, evidence of fabrication, patient behavior, treatment failure, and recurrent disease.3,5

The past health care services use consists in a history of extensive use of medical services, history of peregrination between health care services and multiple medical examinations request.

The atypical presentation includes the manifestation of symptoms when the patient is not under observation, the course of illness is impossible or highly improbable or does not follow the natural history of the presumed diagnosis.

Organic causes are excluded through clinical examination, instrumental diagnostic and laboratory investigations. The evidence of fabrication occurs through search, surveillance, or direct admission by the patient.

The patient’s behavior includes unusual medical knowledge or the use of medical and scientific terms, the extreme eagerness for medical procedures, including invasive ones, attitude of revenge toward health workers, poor adherence to the proposed treatments, pseudologia fantastica, and opposition to the psychiatric consultation instead of medical or surgical procedures. The failure of treatments includes numerous disease relapses and the appearance of new symptoms in conjunction with the treatment or worsening of the medical condition.

To collect the elements of the database for the statistical analysis, missing or doubtful sociodemographic medical and clinical data have been considered as “unknown”. Clinical presentation of FD was extracted on the basis of clinical and diagnostic investigations described in the studies.

IBM SPSS 22 was used to calculate descriptive statistics. Statistical significance was investigated using a Pearson test and linear regression models.

Results

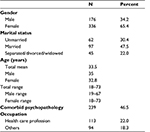

As shown in Table 1, the sample is composed of 34.2% males and 65.4% females. In 0.4% of cases, it was not possible to establish the gender of subjects from the anamnestic data reported. From the data analysis, there is a clear prevalence of the diagnosis of FD in female gender. The average age of general population is 33.5 years (SD 10.6), and the average age of women is 32.8 years (SD 10.9), while that of males is 35 years (SD 9.7).

| Table 1 Basic demographic characteristics of patients diagnosed with FD Abbreviation: FD, factitious disorder. |

As far as the employment is concerned, health care workers account for 22% of the sample (n=113), other professions represent 18.3% (n=94), and the data are unavailable or unreliable for 59.7% (n=307). Despite the unavailable data, in the group in which employment is available (n=207), the number of the nurse is the most significant with the 23.7%. A rate of unemployment of 11.1% was found.

For a large number of patients, the civil status is not available (63.1% of women and 58.6% of men); where this datum is available, a prevalence of married people both in men (17.6%) and women (19.6%) emerged.

In the sample, 28.4% (n=146) of patients present a medical comorbidity and 40.1% (n=206) show one or more psychiatric disorders. The most frequent psychiatric pathologies associated with FD are personality disorders (specifically borderline personality disorder) in 43.1% and depressive disorders in 37.7%. The presence of psychiatric comorbidity is excluded in 39.5% (n=203).

In the family history, the presence of psychiatric diseases and related disorders is positive in 4.9% (n=25) of patients. In most cases (96%), the diagnosis is substance abuse.

With regard to the medical specialties to which factitious patients are concerned, there are minimal differences between the gender of the sample: for men, the most represented specialty is psychiatry (31.5%), followed by emergency department (16.7%) and internal medicine (8%); and for women, the psychiatric ward appears in 22.1% of cases, followed by internal medicine (7.5%) and gynecology (6.5%; Table 2).

A further psychopathological aspect useful for analysis is the subdivision in presentation with internal and external signs/symptoms. Depending on the polarity of the factitious behavior, localization of self-harm may be superficial (e.g. skin ulcers) or internal (e.g. anemia and internal organ damage). The sample shows a prevalence of internal signs/symptoms (87.4%). Thirty-five percent of patients have a positive history for multiple surgical procedures.

As far as the prevalence of all stressful events in correlation with FD is concerned, the following outcomes emerged: 20.2% of the patients show stressful or traumatic events, 14.6% have physical or sexual abuses or neglect in childhood, 16.9% show substance abuse, 10.7% have conflicting and/or unstable interpersonal relationships, and 7.2% reveal premature familiar bereavements. Also, 13.4% of patients present a suicidal behavior.

During hospitalization, 65.8% of patients got a psychiatric consultation. The remaining 34.2% of patients refused or did not have the consultation.

Among the factors considered to be relevant to diagnose these disorders, the exclusion of other organic or psychiatric causes is the most represented, observed in 91.1% of cases.

An atypical presentation is another key issue (89.3%), which implies that the patient’s symptoms or the clinical course of the presumed condition is unusual, sometimes associated with incongruous instrumental findings. In some cases, it is also possible to observe an exacerbation of the symptoms in the presence of the medical staff or, on the contrary, in the absence of any witnesses.

Another important parameter is patient’s unusual behavior (86.2%), followed by treatment failure and/or high disease recurrence (83.7%).

This last point is linked to another parameter that can address such diagnosis, that is, the past use of health services, which in this study has occurred in 72.6% of cases.

Evidence of factitious production has been observed only in 38.1% of cases.

Discussion

The demographic profile of the sample shows a prevalence of female. The data support the hypothesis of several case reports and reviews that FD occur mainly in women.3,9,10 However, other studies published in the literature show a clear prevalence in male gender. This illusory disagreement finds an explanation in Freyberger’s words, who asserts that there is a prevalence of men in clinical trials for Munchausen Syndrome, while the women are most common in the classic form of FD with a ratio of 3:1.11

People affected by FD tend to come to medical attention in young adult age. This outcome, in line with the results of several surveys, supports the datum that FD patients arrive for medical attention in the young adult age.3,12,13

A preponderance of patients with employment in health care emerged. According to a biopsychosocial model and as confirmed by the literature, this finding, although not an absolute majority in patients of this study, suggests that a health care work can be a risk factor in the development of FD if associated with other stressful life events.11,14

A prevalence of married people emerged. Although this result is in contrast to some research in literature, it cannot be excluded that these data are partly conditioned by the impossibility of obtaining this information from the whole sample examined.3,15 This aspect deserves a detailed study in the future.

The study shows a preponderance of comorbidity with personality disorders (specifically borderline personality disorder) and depressive disorders. This outcome is not surprising since the correlation between FD and personality disorders is frequently described in literature.16,17 In the group with comorbidity, personality disorders and depressive disorders are the most represented. There are many studies published in the professional literature that support these connections, but the relationship between these diagnosis is still unclear.18,19

All medical specialties may be interested in the management of factitious patients as evidenced by the clinical heterogeneity of the sample, but the study reveals a prevalence of psychiatry, emergency room, and internal medicine departments. This finding moves away from previous scientific observations. The departments of psychiatry, emergency room, and internal medicine are potentially at risk of receiving patients with FD. These data show that clinical presentation is considerably heterogeneous, but there are some specific clusters of psychiatric, trauma, and neurological signs and symptoms. Despite the fact that there are some previous researches that disclose this aspect,15,20 the psychiatric presentation has never been prevalent in previous studies.3,21 This interesting observation emerged from this review suggests the possibility of underestimation of factitious patients who exhibit psychiatric symptoms and indicates the diagnostic and classification difficulties in patients with psychological signs or symptoms rather than physical ones.

The sample shows a prevalence of internal signs/symptoms, and this could suggest that in FD there is a more marked internal dimension and that patients involve strategies such as falsification of clinical and personal history or pseudologia fantastica in order to keep it hidden. Inner pathologies are confined to a less obvious dimension, in which the act takes place in a hidden, internalized scene and where the subject becomes an executioner of idealistic objects represented in the somatic self, acting as a sadomasochistic connection. The external and visible lesions are intrinsically exposed to the observer’s gaze, and they are more closely related to the traditional concept of hysteria, in which the somatic self-action is loaded with a symbolic and communicative value.22,23

The review highlights the interesting relationship between FD and recurrent surgery addiction. The American psychoanalyst Karl Menninger,24,25 dealing with polysurgery dependence or surgery addiction, considered FD as a suicidal equivalent.

Already, Charcot—known for his studies on hysteria and hypnosis—identified passive operating mania in patients and complementary active operating mania in surgeons. Passive operating mania is an obsessive behavior associated with pain and disability, which entails multiple request of surgical treatments in order to get relief.23

Various authors have tried to outline the psychological dynamic underlying the behavior of these patients. Concerning recurrent surgery, in 1972, Leon Chertok distinguished “polyopérésnévrotiques”, in which relational and psychosexual development disorders prevail, and “polyopéréspsychopathiques”, with characteristics of the so-called Munchausen Syndrome, as the recourse to invasive diagnostic techniques and treatments.26,27

The prevalence of abuse or neglect in childhood, substance abuse, conflicting interpersonal relationships, experience of illness and/or hospitalization in childhood, and premature familiar bereavements discloses the hypothesis of the existence of a common denominator between FD and depressive disorders.28–32

Reich and Gottfried identified that the occurrence of many pathologies during childhood is one of the major factors for the development of an FD.33

As already studied by different authors, these individuals respond to stressful life episodes by implementing pathological behavior as a coping mechanism.34

Many authors believe that patients with FD are at a high risk of suicide. The low percentage emerged, however, is supported by Yates’s recent study, in which only 14.1% of suicidal behavior is observed.3

In the sample, 34.2% of patients refused or did not have the psychiatric consultation. This fact undoubtedly reveals the difficulty of the doctors who rarely can establish a therapeutic alliance with patients. Subjects with FD with physical signs and symptoms unlikely accept to have a psychiatric interview, opposing to it or even get discharged themselves from the hospital.

Among the factors leading to the diagnosis of FD, the exclusion of other organic or psychiatric causes is the most represented. This is undoubtedly important from a diagnostic point of view and because in patients with FD there may be physical or psychic comorbidity that is not diagnosed because of the nature of the disorder itself, which functions as a confounding factor in the clinical presentation.35

In scientific literature, there are some studies that highlight the importance of this aspect, and we hope that in future some guidelines will be drawn, which would help to diagnose FD starting from the unusual clinical presentation.3,5,8

An atypical presentation is another key issue. These patients often use a scientific language without having any expertise in the field and they show knowledge of the medical procedures and keep looking for invasive diagnostic examinations. Such behavior is also characterized by an ambivalent attitude toward the health workers by alternating a collaborative stance and an opposition to the therapeutic program, as well as the use of pseudologia fantastica. In the second case, there are repeated therapeutic failures that do not find an adequate physiological explanation as they are often a consequence of the patient’s repeated pathological behavior.

The difficulty expressed by different authors in trying to reconstruct the clinical history of patients affected by FD is due to the intensive previous use of health services in a significant percentage of cases.

Evidence of factitious production has been observed in limited number of cases, and this highlights the difficulties in discovering the act itself, while preserving patient’s privacy.11

According to the results of this study, several authors have highlighted a frequent comorbidity between FD and depressive disorders,19 as well as a significant correlation between FD and borderline personality disorder.17

The diagnostic criteria for DSM-5 FD were met in 88.7% of cases. The reason for the remaining 11.3% of patients not meeting the criteria can be found in the reclassification that these conditions had in the modern edition of the manual – some patients who first met the criteria of previous editions are now most likely included in another diagnostic category. Medically unexplained symptoms are common and frequent in clinical practice and classifications often have limitations.36 This is an intrinsic feature of manuals such as DSM that tend to designate rigid categories to avoid overlapping, but this inevitably conflicts with the clinical practice where flexibility is essential.

Conclusion

An extensive systematic review on FD published in the professional literature was conducted. The survey of numerous cases had led to draft a demographic profile of the sample highlighting some important points for early diagnosis.

The second end point of this study is to evaluate the evolution of the classification of FD within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. With regard to this aim, the study showed that patients did not meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria in 11.3% of cases; this is due to the fact that the diagnostic reformulation has obviously caused the outplacement of diagnosis of some disease in other new additional sections of the DSM.

This study includes some limitations. First, the choice of case reports implies a bias of publication and selection: it may happen that some authors decide not to publish some cases as they are similar to other works in the literature or because they present already found or less severe manifestations. Another possible limitation is the fact that results of the study are based on case report or case series, as most of the literature on FD, and the design of the studies included is not randomized controlled trials.

In most cases, the diagnosis of personality disorder has not been confirmed by the administration of structured interviews; this could be a possible limitation of the analysis. Finally, it is impossible to exclude some case reports that illustrate the same patient who comes to medical attention in different times and places since sometimes this kind of patients tend to go to various hospitals with a fake identity.

This study lays the foundations for future research that could confirm or deny some hypotheses: first, the prevalence of psychiatric presentations among FD patients and, second, the correlation between FD and depressive syndrome that outlines the possibility of detailed diagnostic and therapeutic study.

The study of FD shows the great difficulty of the physicians to obtain a complete and veritable history from these patients; this aspect inevitably involves confusion and delayed diagnosis, and it exposes these patients to invasive and reiterated investigations.

The reality of general practice could suggest a solution to this problem because general practitioners could have a global clinical view on the patient. In this way, a proposal could be to raise the awareness in all physicians and to create a system that allows a dialog among them in order to protect patients from useless procedures or diagnostic interventions. The goal is an early diagnosis and early psychiatric treatment.

It is also desirable to undertake a thorough research focusing specifically on the group of patients who do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria of the current DSM in order to understand clinical and psychopathological elements beyond the classification.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. | ||

Callegari C, Vender S, Ceccon F, I disturbi Fittizi. In: Callegari C, Poloni N, Vender S, editors. Fondamenti Di Psichiatria. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore; 2013:267–276. | ||

Yates GP, Feldman MD. Factitious disorder: a systematic review of 455 cases in the professional literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;41:20–28. | ||

Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ, Tyerman M. Psychiatric and behavioral correlates of factitious blindness. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(2):159–162. | ||

Steel RM. Factitious disorder (Munchausen’s syndrome). J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2009;39(4):343–347. | ||

Hoertel N, Lavaud P, Le Stratt Y, Gorwood P. Estimated cost of a factitious disorder with 6-years follow up. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2–3):1077–1107. | ||

Bright R, Eisendrath S, Damon L. A case of factitious aplastic anemia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2001;31(4):433–441. | ||

Bass C, Halligan P. Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432. | ||

Krahn LE, Li H, O’Connor MK. Patients who strive to be ill: factitious disorder with physical symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003; 160(6):1163–1168. | ||

Eastwood S, Bisson JI. Management of factitious disorders: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):209–218. | ||

Feldman MD, Eisendrath SJ. The Spectrum of Factitious Disorders. 1st ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1996. | ||

Carney MW, Brown JP. Clinical features and motives among 42 artifactual illness patients. Br J Med Psychol. 1983;56(Pt 1):57–66. | ||

Donegan D, Hickey DP, Smith D. Hypoglycemia after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant: fact or factitious. Pancreas. 2012;41(6):974–976. | ||

Plassmann R. Münchhausen syndromes and factitious diseases. Psychother Psychosom. 1994;62:7–26. | ||

Kanaan RA, Wessel SC. Factitious disorders in neurology: an analysis of reported cases. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(1):47–54. | ||

Limosin F, Loze JY, Rouillon F. Clinical features and psychopathology of factitious disorders. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 2002;153(8):499–502. | ||

Nadelson T. The Munchausen spectrum: borderline character features. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1979;1(1):11–17. | ||

Gordon DK, Sansone RA. A relationship between factitious disorder and borderline personality disorder. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11–12):11–13. | ||

Earle JR, Folks DG. Factitious disorder and coexisting depression: a report of successful psychiatric consultation and case management. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1986;8(6):448–450. | ||

Bretz SW, Richards JR. Munchausen syndrome presenting acutely in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2000;18(4):417–420. | ||

Nicholson SD, Roberts GA. Patients who (need to) tell stories. Br J Hosp Med. 1994;51(10):546–549. | ||

De Martis D, Vender S, Barale F. Atti del XXXVII Congresso Nazionale SIP. In: Progressi in Psichiatria. Standard Diagnostici ed Epidemiologia. I disturbi fittizi: aspetti clinici e psicodinamici. Roma: CIC Edizioni Internazionali; 1989. | ||

Callegari C. I Modelli Interpretativi dei Disturbi Fittizi. In: S. Vender, editor. La Maschera Della Finzione. Roma: Il pensiero scientifico editore; 1997:63–75. | ||

Callegari C, Caperna S, Isella C, Bianchi L, Vender S, Poloni N. Multiple surgical interventions: diagnosis and psychopathology in recurrent operated patients. Minerva Psichiatrica. 2014; 55(4):215–223. | ||

Menninger KA. Polysurgery and polysurgic addiction. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1934;81(1):93. | ||

Callegari C, Caselli I, Bianchi L, Isella C, Vender S. Four clinical cases of recurrent surgery addiction (polyopérés): diagnostic classification in the DSM-IV-TR vs DSM-5. Neuropsychiatry. 2016;6(4):178–184. | ||

Callegari C, Bortolaso P, Vender S. A single case report of recurrent surgery for chronic back pain and its implications concerning a diagnosis of Münchausen syndrome. Funct Neurol. 2006;21(2):103–108. | ||

Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11): e1001349. | ||

Bovasso GB. Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(12):2033–2037. | ||

Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106(5):906–914. | ||

Gao J, Li Y, Cai Y, et al. Perceived parenting and risk for major depression in Chinese women. Psychol Med. 2012;42(5):921–930. | ||

Geracioti TD, Van Dyke C, Mueller J, Merrin E. The onset of Munchausen’s syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9(6):405–409. | ||

Reich P, Gottfried LA. Factitious disorders in a teaching hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99(2):240–247. | ||

Merrin EL, Van Dyke C, Cohen S, Tusel DJ. Dual factitious disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1986;8(4):246–250. | ||

Poloni N. Vender S, Bolla E, Bortolaso P, Costantini C, Callegari C. Gluten encephalopathy with psychiatric onset: a case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:16. | ||

Ferrari S, Poloni N, Diefenbacher A, Barbosa A, Cosci F. Modern psychopathologies or old diagnoses? From hysteria to somatic symptom disorders: searching for a common psychopathological ground. J Psychopathol. 2015;21(1):372–379. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.