Back to Journals » Clinical Optometry » Volume 9

Determinants of high unmet need for presbyopia correction: a community-based study in northwest Ethiopia

Authors Girum M , Desalegn Gudeta A, Shiferaw Alemu D

Received 4 October 2016

Accepted for publication 21 December 2016

Published 23 January 2017 Volume 2017:9 Pages 25—31

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTO.S123847

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Mr Simon Berry

Mikael Girum,1 Alemayehu Desalegn Gudeta,2 Destaye Shiferaw Alemu2

1Department of Ophthalmology and Optometry, College of Medicine and Health Science, Hawassa University, Awasa, 2Department of Optometry, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Purpose: Lack of evidence on the magnitude of unmet presbyopia need, and barriers to uptake spectacles, limit appropriate planning and implementation of the provision of spectacles to address the backlog of uncorrected presbyopia. The purpose of this study was to determine the magnitude of unmet presbyopia need and the associated factors in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

Materials and methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in 2015 in Bahir Dar. A multistage sampling technique was used to sample 729 study participants. Individuals more than 35 years of age who were unable to read the N8 line on a near vision chart unaided or with existing spectacles at 40 cm were considered as having unmet need for presbyopia correction. Distance and near visual acuities were measured by optometrists using Snellen illiterate E chart at 6 m and 40 m, respectively. Data were entered into Epi Info 2002 and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16.0. Odds ratio (with 95% confidence interval [CI]) was used to determine the strength of association. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results: A total of 729 people were included in the study (response rate of 99.5%). The mean age ± standard deviation of participants was 48.9±8.8 years. Unmet presbyopic need was 69.2% (95% CI: 65.8%–72.6%). Age (36–45 years [adjusted odds ratio {AOR} = 3.95; 95% CI: 1.06, 4.80]), having no eye checkup in the past 1 year (AOR = 8.36; 95% CI: 5.16, 13.7), lack of awareness about place of refraction service (AOR = 4.38; 95% CI: 1.36, 13.7), and female gender (AOR = 1.78; 95% CI: 1.68, 2.9) were determinants of unmet presbyopia need.

Conclusion: The burden of unmet presbyopia need is a high priority according to the World Health Organization prioritization for provision of presbyopia services. Accessible and affordable provision of spectacles with health education and promotion efforts are imperative to address the backlog of unmet presbyopia correction need in the study area.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Bahir Dar, presbyopia, unmet need

Introduction

Worldwide, there are an estimated 1.04 million people with presbyopia,1 many of whom were without adequate correction in 2005.2 This figure is predicted to increase to 1.4 billion by 2020 and to 1.8 billion by 2050.3 It has been estimated that 67% of people with presbyopia live in the developing regions of the world where access to correction is constrained.3,4 The onset of presbyopia is when people are in their early 30s, especially in hot areas of the world, and its severity increases until 55 years of age.5

Uncorrected presbyopia causes near visual impairment with symptoms of headaches, eye strain and the need to hold objects further away from eyes.1 It affects not only reading and writing but also compromises all aspects of quality of life in populations where reading and writing are less a part of daily life.6 The quality of life in people who cannot read and write may affect their income as vision will be affected in activities related with livelihood activities such as sewing, tailoring and any other activities that need fine view. Presbyopia may also affect people’s quality of life in terms of communication where nowadays communication is carried out with the help of mobiles. If presbyopia is untreated, a significant functional visual disability is likely to develop.1–3 The economic consequences of uncorrected presbyopia are considerable as it affects people in the working age group.7,8

When prioritizing for the provision of presbyopia services, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended that if less than one-third has near correction, the population would be ranked as a high priority for service delivery. If one-third to two-thirds have spectacles, the priority ranking would be moderate, and if more than two-thirds have spectacles, it would be low.9

A rural based study has shown that setting a target ratio of 1 trained optometrist to a population of 600,000 in developing countries is needed to meet the WHO vision 2020, the right to sight, mission.4 It is also indicated that adults over the age of 40 years are principal targets for provision of near spectacles.4,10

There are different options for presbyopia correction. However, spectacles are the cheapest, most convenient and affordable correction means, especially in developing countries where other options are infeasible.11,12 However, there are barriers to utilize them. Gender (female), high cost of spectacles, illiteracy and lack of awareness about place of service where presbyopia correction is rendered, access to health care services and non-availability of optometrists and other auxiliary ophthalmic personnel are paramount barriers for use of spectacles for presbyopia correction.11,13,14

Accurate estimate of unmet presbyopic need and identifying associated factors are paramount in appropriate eye care response needed. An accurate estimate of the magnitude of uncorrected presbyopia and identifying the associated factors plays a key role in planning appropriate eye care service for presbyopia correction. However, there is little evidence on the magnitude of uncorrected presbyopia and the associated factors in Ethiopia, particularly in a study setting. This study aimed to determine the magnitude of unmet presbyopic correction need and to identify the associated factors among people aged more than 35 years of age in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Bahir Dar, one of the reform towns in Amhara National Regional state of Ethiopia, has a city administration, metropolitan administration and 9 urban and 4 rural sub-cities.

According to the Ethiopian National Housing and Census Statistical Agency,15 the population of the town was 170,267. Out of this, 75,302 (44%) were males and 94,965 (56%) were females. Sixty-seven percent of the town population (114,078) was within 16–60 years and 3% (5,108) was aged 61 years and above. There are 1 government and 1 private hospital, 3 private eye clinics and many optical shops in the town.

A community-based cross-sectional study was carried out employing multistage random sampling to select study participants. Initially, 2 urban and 1 rural administrative areas were selected using simple random sampling technique. After taking into account residence type (urban or rural) and household size, a proportional allocation for each administrative area was established, then systematic random sampling was used to select households (with sampling fraction of k = 13), where k is the number of households divided by the sample size (ie, 9477/729) in order to select households using systematic random sampling, a prominent landmark (road that divides the study area in 2) was identified and data collectors toss a coin in which to start. Then, a number between 1 and 13 was selected and the number selected was the first household to be included in the sample and every 13th household was included in the sample provided that there was n eligible person for the study. Lottery method was applied to select study participants in households where more than 1 person eligible for the study lives. The assumption was that there was at least 1 adult (age >35 years) in each household who fulfills the inclusion criteria. In case where this assumption did not hold, the immediate next household was included, provided that the former assumption held.

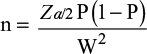

Sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula, which is |

here P = proportion of unmet presbyopia correction of 17.5% (based on a study in Zanzibar),16 Z = 1.96 (the value of Z statistic at 95%), W = maximum allowable error (margin of error = 5%). Taking into account a design effect for multistage sampling of 2 and a non-response rate of 10%, the minimum final sample size was 729.

Permanent residents (age >35 years living at least 6 months in the study area) were the source population. Individuals with ocular conditions, which can affect near vision, and individuals with communication problem were excluded from the study.

Individuals older than 35 years who did not achieve the N8 line on a near vision chart unaided or with their existing spectacles at 40 cm, but improved to N8 or better with correction were considered as having unmet presbyopic need. Presbyopia was considered in people who were older than 35 years with presenting distance vision better than 6/12 and presenting near vision worse than N8 at 40 cm. Presbyopia was considered non-correctable when a person with presenting near vision worse than N8 at 40 cm was not able to see N8 or more despite the amount of plus lens given at 40 cm.

Distance unaided vision/habitual visual acuity was measured using illiterate E chart at 6 m. Visual acuity testing was performed during daylight hours outdoors under ambient light conditions. Measurement was taken separately for each eye. Retinoscopy was carried out using a streak retinoscope and refined subjectively. Subjects with uncorrected binocular near visual acuity <N8 underwent binocular refraction at 40 cm, with best corrected near visual acuity obtained by testing with spherical lenses of increasing plus power. The minimum positive lens power required to read ≥ N8 was determined in a step of ±0.25 DS. Direct ophthalmoscopy was done for those participants whose vision did not improve with correction and sent to the nearby hospital for further evaluation.

In order to ensure data quality, questionnaires (to collect sociodemographic data and the reasons not to seek spectacles for correction) were translated from English to a local language, Amharic, and then back to English by language expert for consistency. The questionnaire was separated in 2 sections with sociodemographic data and questions related to reasons not to seek spectacles. A pretest was carried out (on 5% of the sample size) in Gondar. Collected data were checked for completeness on daily basis by supervisor. One-day training was given to data collectors (optometrist) on the study protocol.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Medicine, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar. Support letter from respective administrative, urban and rural sub-city was obtained. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. As this study was a questionnaire based cross sectional study, the Ethical Review Committee of the School of Medicine did not require that written consent be obtained. Participation was on voluntary basis. Confidentiality was maintained by coding personal identity and locking data with password in a computer. Prescription for correction was provided for those individuals with refractive error and/or presbyopia. Education related to use of presbyopic spectacles was given to all participants. Referrals with acute and chronic ocular diseases were considered for further ocular examination.

Coded data were entered into Epi Info 2002 and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 16.0. Descriptive statistics and tables were used to summarize proportion of unmet presbyopic spectacles need and demographic variables. Binary and multivariate logistic regressions fitted to identify factors associated with unmet presbyopic need. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to assess the strength of association. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 729 people participated in this study. The response rate was 99.5%. The mean age of the study population was 48.9 years (±8.8 standard deviation). The male to female ratio was 2.1:1. In all, 496 participants (68%) were males and 233 (32%) were females. This difference was not statistically significant (P>0.05); 696 participants (95.5%) were urban residents and 33 (4.5%) were rural residents though not statistically significant (P>0.05). A total of 221 participants (30.3%) were unable to read and write and 321 (44%) had a monthly household income of 1001–2000 Ethiopian birr. Two-hundred seventy (35.7%) of them were unemployed (Table 1).

| Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants of Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia, 2015 (n=729) |

Prevalence of unmet presbyopic correction need

From 729 study participants, 97.1% (712) had correctable presbyopia, whereas 6.9% (17) of them had presbyopia but non-correctable (and a few were not presbyopic). Therefore, among correctable presbyopia, the prevalence of unmet presbyopic spectacles need was 69.2% (493). The unmet need in males, married and those who were unable read and write were 71.2% (351), 83.6% (412) and 32.3% (159), respectively. The prevalence of unmet need observed in urban residents and in the age group 46–55 years was 95.5%, and 45.6%, respectively (Table 2).

| Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of unmet presbyopic need among people aged above 35 years in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia, 2015 Abbreviation: ETB, Ethiopian birr. |

Factors associated with unmet presbyopic correction need

In the bivariate regression, age (36–45 years), female gender, educational status (grade 1–8), no eye checkup in the past 1 year and lack of awareness about place of refraction were significantly associated with unmet presbyopic need. However, in the multivariate analysis, age 36–45 years (OR = 3.95; 95% CI: 1.06, 4.80), no eye checkup in the past 1 year (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 8.36; 95% CI: 5.16, 13.7), female gender (AOR = 1.78; 95% CI: 1.68, 2.9) and lack of awareness about place of refraction (AOR = 4.38; 95% CI: 1.36, 13.7) were independent determinants of unmet presbyopic need. Accordingly, individuals in the age group of 36–45 years were nearly 4 times more likely to have unmet presbyopic need compared with individuals aged 66 years and above. Individuals having no eye checkup in the past 1 year were more than 8 times more likely to have unmet presbyopic need compared with those individual having an eye checkup in the past 1 year. Similarly, individuals who lack awareness about place where refraction takes place were more than 4 times more likely to have unmet presbyopic need relative to their counterparts who are aware of place of refraction (Table 3). In this study, monthly income, type of occupation, educational level, and residence type (urban or rural) were not determinants of unmet need for presbyopia correction.

Discussion

This study revealed the burden of unmet presbyopic correction need and factors associated with it in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. The study used a definition of unmet presbyopic correction need in individuals aged above 35 years who were unable to see N8 unaided or with their existing correction.

The unmet presbyopic correction need in this study was 69.2% (95% CI: 65.8%–72.6%), which implies a high priority for presbyopia correction in the study area. According to the WHO prioritizing provision of presbyopic services, if more than two-thirds of the people who are in need for presbyopia correction are without correction the population would be ranked as high priority for service delivery.9

The unmet presbyopic correction need in the present study is worse than reports from other developing countries like Timor-Leste (32.2%),11 Andhra Pradesh, India (41.9%),17 Marine (40.1%)12 and Nigeria (42.1%).18 This might be due to the difference in eye care service and availability of spectacles between these countries. Studies have suggested that a high proportion of near vision may go uncorrected in areas of limited resources.12,19 On the contrary, this finding is lower than a report from rural settings of Australia (81.1%),20 Kenya (80.0%)4 and Nepal 90%,21 which may reflect the unmet presbyopic need of worse in rural setting of developing countries.4 This might also be account for the reasonable access to health care in urban populations of better economy.22

In this study, age (36–45 years), female gender, lack of awareness about place of refraction service and having no eye checkup in the past 1 year were determinants of unmet presbyopic need correction.

Individuals between age 36 and 45 years were nearly 4 times more likely to have unmet presbyopic need compared with their counterpart aged 66 years and above. Similar findings were reported from rural Tanzania where 62.5% of people aged 40 years had no corrective lens despite the fact that 94.1% of them had near vision problems.23 This may be due to people in the working age group (36–45 years) feeling a higher need for near correction compared to those people in the non-working older age group. In the present study, the participants were more likely to be involved in near-vision-demanding tasks, as they were predominantly urban residents (95.5%) and worked in government organizations (24.3%) (Table 1). Evidence from a study in rural Kenya showed that with increasing age, the prevalence of functional presbyopia significantly decreased.4 This might be due to the fact that older people may require less help for near vision, as they are likely to develop cataract, which leads to myopic shift and some near vision problems may not be correctable due to the onset of uncorrectable age-related ocular diseases.16 The other possible explanation might be that older people are most likely retired and hence near-vision-demanding tasks will be reduced. For example, in this study, 37% (Table 1) of the participants were retired. On the contrary, older age was significantly associated with unmet presbyopic correction need in Nepal21 and Durban, South Africa.24

The odd of unmet presbyopic correction in females was nearly double compared with males. Earlier study conducted in South India also showed a slightly better spectacle coverage (52%) in males than in females (46%).25 This may be due to the presence of severe, higher and earlier onset26,27 of presbyopia in women compounded by the less opportunity to afford spectacles and the fact that they are less likely to know where to get spectacles.28 In the urban population of Iran, economic inequality plays a significant role in having correction for visual impairment among women with low economic status.29

Lack of awareness about place of refraction service was the other determinant for unmet presbyopic correction need in the present study. In Zanzibar, lack of awareness was regarded as a barrier to access spectacles.16 Similarly, in a population-based cross-sectional study in South India, awareness about the presence of service was an important barrier as reported by people with uncorrected presbyopia.30 In Nampula, Mozambique, 13% people with visual impairment had no awareness about the place of refraction service.31

In the present study, having no eye checkup in the past 1 year was the most determinant factor for unmet presbyopic correction. It is important to note that utilization of refraction services is just as important as provision of services to address the burden of uncorrected presbyopia.32 Even though there are many underlying factors that determine eye checkup, possible reasons for not having eye checkup might be due to limited eye care center and cost. For example, in the study area, there is only 1 eye care center and majority of the optical workshops are private and possibly costly. Availability of spectacles, availability of refractive services and quality of refractive services are identified barriers to address uncorrected refractive errors in earlier studies.11,13,14,33

Unlike previous studies,16,17,33 educational status was not a determining factor for unmet presbyopic need in this study. Earlier similar study in Andhra Pradesh depicted that the unmet need for presbyopia was associated with the level of education. This makes sense that near spectacles correction is not only useful for reading and writing but also for other non-pen-paper-related activities.

Adequate sample size, good response rate in sampling and population-based design, which make the estimates reliable, are the main strengths of this study. It also allowed for an investigation of factors for not wearing near spectacles among those needing them.

Nevertheless, one should note that the results have been obtained from a cross-sectional study and the relationships identified are not necessarily causal. In this study, the effect of income and cost of the spectacles on unmet need was not assessed, which were reported as major barriers to access spectacles in former studies.13,14,31 Additionally, measurement of visual acuity lacks consistency because of illumination variation while taking visual acuities from home to home. This may either overestimate or underestimate the near visual acuity based on the level of illumination. Another limitation of this study is that individuals with low/moderate myopia may not need positive lenses for near vision, which may result in underestimation of unmet presbyopic correction need.

To summarize, more than two-thirds of people with presbyopia in Bahir Dar have no correction. Age, female gender, lack of awareness about place of refraction service and having no eye checkup in the past 1 year are the main factors affecting presbyopia correction. The study also revealed high prevalence of unmet need for near vision correction, most strikingly in the economically important population of working age population (36–45 years).

Accessible and affordable provision of spectacles with health education and promotion efforts are imperative in the study area to address the backlog of unmet presbyopic correction need in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. The findings will also assist the local Ministry of Health officials in their planning of refractive error services, which may include outreach programs and vision centers in the study area. Given the high prevalence of presbyopia, this study has major implications for the WHO Vision 2020 refraction agenda, which should place greater emphasis on presbyopia. The findings of this study also have an implication on provision of spectacles for near vision, which remains as a priority in low-income countries. Studies that will address potentially complex factors, which cannot be addressed with survey questions, are recommended to dig out more factors explaining the disparity between the burden and unmet presbyopic correction need.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to University of Gondar for its financial support, Bahir Dar administration office for its cooperation, and the study participants.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript, read and approved the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Patel I, West SK. Presbyopia: prevalence, impact, and interventions. Community Eye Health. 2007;20(63):40–41. | ||

Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of vision impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):614–618. | ||

Holden BA, Fricke TR, Ho SM, et al. Global vision impairment due to uncorrected presbyopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(12):1731–1739. | ||

Sherwin JC, Mathenge W. Presbyopia, related functional impairment, and spectacle use in Rural Kenya. Int Health. 2008;(6):8–10. | ||

Mancil GL, Bailey IL, Brookman KE, et al. Optometric clinical practice guideline: care of the patient with presbyopia. Reference Guide for Clinicians. St Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; 2006:20–21. | ||

McDonnell PJ, Lee P, Spritzear K, Lindblad AS, Hays RD. Associations of presbyopia with vision-targeted health-related quality of life. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(11):1577–1581. | ||

Laviers H, Burhan I, Omar F, Jecha H, Gilbert C. Evaluation of distribution of presbyopic correction through primary health care centres in Zanzibar, East Africa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(6):783–787. | ||

Alamu TO, Fomete DM, Akubo IU, Wuraola FO. Profile of eye camp: an assessment of presbyopia among people. Arch Appl Sci Res. 2011;3(4):509–512. | ||

Laviers HR, Omar F, Jecha H, Kassim G, Gilbert C. Presbyopic spectacle coverage, willingness to pay for near correction, and the impact of correcting uncorrected presbyopia in adults in Zanzibar, East Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(2):1234–1241. | ||

Uche JN, Ezegwui IR, Uche E, Onwasigwe EN, Umeh RE, Onwasigwe CN. Prevalence of presbyopia in a rural African community. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(3):2731. | ||

Ramke J, du Toit R, Palagyi A, Brian G, Naduvilath T. Correction of refractive error and presbyopia in Timor-Leste. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(7):860–866. | ||

Marmamula S, Keeffe JE, Rao GN. Uncorrected refractive errors, presbyopia and spectacle coverage: results from a rapid assessment of refractive error survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16(5):269–274. | ||

Adapa P, Savur S. Unmet presbyopia: unearthing the iceberg - reasons and remedies. A pilot study in Rural Dakshina Kannada. IOSR-JDMS. 2016;15(6):4–10. | ||

Nirmalan PK, Krishnaiah S, Shamanna BR, Rao GN, Thomas R. A population-based assessment of presbyopia in the state of Andhra Pradesh, south India: the Andhra Pradesh eye disease study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(6):2324–2328. | ||

Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency (CSA).National Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia projection, 2011. Available from: http://www.csa.gov.et/. Accessed November 12, 2015. | ||

He M, Abdou A, Ellwein LB, et al. Age-related prevalence and met need for correctable and uncorrectable near vision impairment in a multi country study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):417–422. | ||

Marmamula S, Ravuri LV, Boon MY, Khanna RC. Spectacle coverage and spectacles use among elderly population in residential care in the south Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:183502. | ||

Muhammad RC, Jamda MA. Presbyopic correction coverage and barriers to the use of near vision spectacles in rural Abuja,Nigeria. Sub-Saharan Afr J Med. 2016;3(1):20–24. | ||

Lu Q, He W, Murthy GV. Presbyopia and near-vision impairment in rural northern China. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(5):2300–2305. | ||

Wubben TJ, Guerrero CM, Salum M, Wolfe GS, Giovannelli GP, Ramsey DJ. Presbyopia: a pilot investigation of the barriers and benefits of near visual acuity correction among a rural Filipino population. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014;14:9. | ||

Sapkota YD, Dulal S, Pokharel GP, Pant B, Ellwein LB. Prevalence and correction of near vision impairment at Kaski, Nepal. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2012;4(7):17–22. | ||

Foster A, Resnikoff S. The impact of Vision 2020 on global blindness. Eye (Lond). 2005;19(10):1133–1135. | ||

Patel I, Munoz B, Burke AG, et al. Presbyopia: impact on quality of life in a rural African setting. Ophthalmology. 2005;46(13):13–15. | ||

Naidoo KS, Jaggernath J, Martin C, et al. Prevalence of presbyopia and spectacle coverage in an African population in Durban, South Africa. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90(12):1424–1429. | ||

Pema R, George R, Sathyamangalam Ve R, et al. Comparison of refractive errors and factors associated with spectacle use in a rural and urban South Indian population. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2008;56(2):139–144. | ||

Patel I, Munoz B, Burke AG, et al. Impact of presbyopia on quality of life in a rural African setting. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(5):728–734. | ||

Burke AG, Patel I, Munoz B, et al. Population-based study of presbyopia in rural Tanzania. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(5):723–727. | ||

Patel I, Munoz B, Burke AG, et al. Presbyopia: outcomes after refractive correction in rural Tanzania. Submitted to BJO. | ||

Emamian MH, Zeraati H, Majdzadeh R, et al. Economic inequality in presenting near vision acuity in a middle-aged population: a Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(9):1100–1103. | ||

Marmamula S, Mdala SR, Rao GN. Prevalence of uncorrected refractive errors, presbyopia and spectacle coverage in marine fishing communities in South India: Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment (RAVI) project. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32(2):149–155. | ||

Thompson S, Naidoo K, Gonzalez-Alvarez C, Harris G, Chinanayi F, Loughman J. Barriers to use of refractive services in Mozambique. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92(1):59–69. | ||

Marmamula S, Keeffe JE, Raman U, Rao GN. Population-based cross-sectional study of barriers to utilisation of refraction services in South India: Rapid Assessment of Refractive Errors (RARE) Study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1):e000172. | ||

Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(1):63–70. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.