Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 12

Conventional trabeculectomy versus trabeculectomy with the Ex-PRESS® mini-glaucoma shunt: differences in postoperative interventions

Authors Tojo N , Otsuka M, Hayashi A

Received 20 December 2017

Accepted for publication 13 February 2018

Published 3 April 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 643—650

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S160342

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Naoki Tojo, Mitsuya Otsuka, Atsushi Hayashi

Department of Ophthalmology, Graduate School of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Toyama, Toyama, Japan

Purpose: To compare the postoperative interventions and outcomes between conventional trabeculectomy and trabeculectomy with the Ex-PRESS® mini-glaucoma shunt device (Ex-Press).

Methods: This was a retrospective, comparative, single-facility study. We analyzed the cases of 108 glaucoma patients who underwent trabeculectomy and were followed for >1 year. Thirty-nine eyes underwent a conventional trabeculectomy (conventional group) and 69 eyes underwent a trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press (Ex-Press group). As evaluation items, we examined postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP), the surgical success rate, postoperative complications, the number of days to laser suture lysis, and needling.

Results: Trabeculectomy significantly decreased the patients’ IOP values from 27.8±7.9 to 11.1±3.9 mmHg in the conventional group (p<0.001) and from 27.7±9.2 to 11.5±3.7 mmHg in the Ex-Press group (p<0.001) after 1 year. The success rate was not significantly different between the groups. The timing of the first laser suture lysis was significantly sooner in the Ex-Press group, and the Ex-Press group showed significantly less choroidal detachment due to low IOP.

Conclusion: Earlier laser suture lysis in patients whose trabeculectomy treatment includes an Ex-Press is required to obtain the outcomes comparable to those of conventional trabeculectomy.

Keywords: Ex-Press, glaucoma, trabeculectomy, postoperative management, laser suture lysis

Introduction

Trabeculectomy is a surgical filtering method that is widely used in the treatment of glaucoma. In recent years, trabeculectomies using an Ex-PRESS® mini-glaucoma shunt device (Ex-Press; Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX, USA) have been conducted worldwide.1 The Ex-Press is a stainless-steel filtration device designed to shunt the aqueous humor from the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space.

In a trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press, there is no need to remove the trabecular meshwork and the peripheral iris, and thus, this technique is less invasive than a conventional trabeculectomy. Since there is less risk of hypotony, the outcomes of trabeculectomy with the Ex-Press were reported to involve fewer complications due to hypotony (shallow anterior chamber, choroidal detachment, and hypotony maculopathy) compared with conventional trabeculectomy.2–6

In a number of studies, the outcomes of trabeculectomy with the Ex-Press were reported to be equivalent to those of conventional trabeculectomy.4–13 However, there are several investigations that have compared postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP), complications, and the speed of vision improvement between conventional trabeculectomy and trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press;4,12,13 few studies have compared the postoperative management between these two versions of trabeculectomy.7,13

In the present study, we retrospectively compared the postoperative IOP, the success rate for postoperative IOP decline, the rate of postoperative complications, and the rate of postoperative interventions between conventional trabeculectomy and trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

This was a retrospective, nonrandomized observational study. We analyzed the cases of 108 consecutive patients (124 eyes) who underwent a trabeculectomy for the first time at Toyama University Hospital and were followed for >1 year. There were 16 patients who underwent trabeculectomy in both eyes, and in these cases, we used unilateral data of the eye that was operated earlier. All subjects were recruited during the period from December 2011 to August 2016. All patients underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination including refraction, Goldmann gonioscopy, Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT), fundus examination, automated perimetry (Humphrey Field Analyzer; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA), and measurement of central corneal thickness (CCT) and anterior chamber depth with anterior segment optical coherence tomography (CASIA SS-1000; Tomey, Nagoya, Japan). Two glaucoma specialists (NT and AH) diagnosed all the cases of glaucoma.

The patients had already used tolerated glaucoma medications, and they had needed further treatment to lower their IOP because of the progression of their visual field disorder. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Toyama, and the procedures used conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. After explaining the nature and possible consequences of the study to the patients, written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

The preoperative (baseline) IOP was the mean of the IOPs recorded at three of the patient’s visits while on preoperative treatment. The IOP was measured using GAT. We separated the patients into two groups. The eyes that underwent conventional trabeculectomy were defined as the conventional group, and the eyes that underwent trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press were defined as the Ex-Press group.

Surgical techniques

We performed conventional trabeculectomy before November 2013, and after that, we performed trabeculectomy with Ex-press. Since Ex-press is contraindicated for use in patients with uveitis or primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG), we performed conventional trabeculectomy for these cases even after November 2013. All patients were operated on by one surgeon (NT). Retrobulbar anesthesia was administered. A standard fornix-based conjunctival incision was made to gain exposure to the scleral bed adjacent to the limbus. A single 3.5-mm2 square scleral flap was created. Mitomycin C (MMC) solution (0.04 mg/mL) was applied for 4 min. At this point, the eye was a completely enclosed space, and thus, the MMC solution could not flow into the anterior chamber. The treated area was then irrigated with ~100 mL of balanced salt solution. If the patient needed simultaneous cataract surgery, the cataract surgery was performed at this time. Regarding surgical indication of cataract surgery, it is a retrospective study, no clear criteria had been established, and cataract surgery was performed according to the judgment of the operator.

In the cases of conventional trabeculectomy, a sclerotomy was performed, and the trabecular meshwork was removed. A peripheral iridectomy was performed. In the cases of trabeculectomy with the Ex-Press, the scleral flap was lifted and a 25-ga. needle was inserted horizontally into the anterior chamber at the surgical limbus to create a path for the Ex-Press (model P50); the 25-ga. needle was inserted into the anterior chamber from the sclera–cornea transition zone parallel with the iris. The Ex-Press was then inserted into the anterior chamber.

In both the conventional cases and the Ex-Press cases, the scleral flap was sutured using a 10-0 nylon suture, adjusting the tension on the sutures to maintain anterior chamber depth with slow flow of aqueous humor around the margins of the scleral flap. In addition, the conjunctiva was meticulously closed with a 10-0 nylon suture. We confirmed that there was no leakage from the blebs.

Postoperative medication

The postoperative treatments were topical medications of steroids, antibiotics, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The steroids and antibiotics were reduced over the 4 weeks following the interventions. NSAIDs were reduced over a 12-week period after the interventions. The antiglaucoma medications were added at the discretion of the physicians. We counted a compounding agent as two medications.

Postoperative interventions

We examined whether there was a difference between the conventional and Ex-Press groups among the patients who underwent laser suture lysis and needling. We also investigated the number of days until laser suture lysis and needling. The operator judged which suture thread to cut and when to cut it. We used a multicolor laser (MC-500; Nidek, Nagoya, Japan) for the laser suture lysis, which was performed with a krypton laser (red) after premedication with topical 0.4% oxybuprocain. A suture lysis lens (Blumenthal, Volk Optical, Mentor, OH, USA) was used to compress and blanch the conjunctiva over the suture to be cut. Laser parameters included a 50-μm spot size, a 0.2 s, and 250 mW power.

Needling has various purposes including enlarging the bleb for lowering the IOP, but it also functions to prevent adhesions and to cut the thread, lift the scleral flap, and suppress the leakage.14 In this study, we adopted needling which obviously aimed at lowering the IOP. We used a bleb knife (KAI Group, Tokyo, Japan) for needling after subconjunctival injection with topical 4% Xylocaine (lidocaine HCl). There were no cases in which medicines with cytostatic action such as MMC and 5-fluorouracil were used.

Definition of success

The two main criteria of successful treatment that we used were Criterion A and Criterion B. Success according to Criterion A was postoperative IOP ≤21 mmHg or a ≥20% reduction from the baseline on two consecutive visits after the first postoperative month. Success according to Criterion B was defined as postoperative IOP ≤15 mmHg or a ≥20% reduction from the baseline on two consecutive visits after the first postoperative month. Cases were considered treatment failures if neither of the success criteria were met at two consecutive visits after the first postoperative month. Eyes requiring additional glaucoma surgery and those that developed phthisis or showed loss of light perception were classified as failures.

Statistical analysis

A paired t-test and Fisher’s exact test were used for the comparisons of the conventional and Ex-Press groups. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for the comparison of same patients of IOP and glaucoma medications. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests were used for the comparison of the success rate. All of the statistical analyses were performed with JMP Pro 11 software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Significance was defined as p-values <0.05.

Results

Ophthalmic data

The characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. We analyzed the cases of 108 patients: 55 males and 53 females. The mean (±SD) values for all 108 patients are as follows: age at the time of surgery, 70.2±10.7 years; CCT, 533±40 μm; the follow-up period, 33.3±14.1 months; the number of glaucoma medications, 4.0±1.0 drops; and preoperative IOP, 27.7±8.7 mmHg. All of these parameters except for the follow-up period did not differ significantly between the two groups. The number of threads of scleral flap suture was significantly higher in the conventional group (4.3±1.0) than in the Ex-Press group (2.7±1.0) (p<0.001). Eighty-two eyes underwent a trabeculectomy alone, and the other 26 patients with a phakic eye underwent cataract surgery and a trabeculectomy at the same surgery session.

We classified the subtypes of glaucoma as primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), pseudo-exfoliation glaucoma (PEXG), secondary glaucoma (SG), and PACG. The conventional group had significantly more cases of SG than the Ex-Press group (p=0.0011). All cases of SG who performed conventional trabeculectomy were due to uveitis. We selected Ex-press for one case of SG. This case was steroid glaucoma, and no inflammatory disease was observed in the eye. Since the scleral bed was too thin or the insertion site of Ex-Press was incorrect, there were three cases in which Ex-Press could not be inserted, and these cases were converted to conventional trabeculectomy.

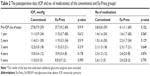

Postoperative IOP and number of medications used

Table 2 summarizes the postoperative data of the conventional and Ex-Press groups. The results of the eyes that underwent additional glaucoma surgeries were excluded. The mean postoperative IOP and the mean number of glaucoma medications were not significantly different between the two groups at any time point. We compared the surgical results of POAG and PEXG, and there was no significant difference in postoperative IOP, the number of postoperative medications, and the success ratio between the two groups. We also compared surgical results of the Single surgery (trabeculectomy alone or Ex-Press alone) and the Triple surgery (simultaneous cataract surgery). The patients who underwent the Triple surgery were 8 eyes (POAG: 6 eyes, PEXG: 2 eyes) in the conventional group; and 18 eyes (POAG: 10 eyes, PEXG: 8 eyes) in the Ex-Press group. There was no significant difference in postoperative IOP, the number of postoperative medications, and the success ratio between the two groups (Table 3). In all of the cases who had undergone the Triple surgery, the anterior chamber was deep, the mean of the preoperative anterior chamber depth was 2.84±0.61 mm, and the minimum value was 2.2 mm. In a case of PACG, we performed cataract surgery alone, but the reduction in IOP was insufficient. So, we performed conventional trabeculectomy.

| Table 3 Comparison of the results between Single and Triple surgeries |

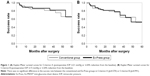

Success rate

We performed a Kaplan–Meier analysis to determine the success rates of the conventional and Ex-Press groups and compare them (Figure 1) for both Criterion A and Criterion B. The success rate was not significantly different between the conventional and Ex-Press groups when using Criterion A (log-lank test: p=0.570) or when using Criterion B (log-rank test: p=0.991).

The failure rate using Criterion A was 7 of 39 eyes (17.9%) in the conventional group, and the corresponding rate in the Ex-Press group was 13 of 69 eyes (18.8%). The reasons for failure were as follows: In the conventional group, a need for additional glaucoma surgery occurred in six eyes, and loss of light sensation developed in one eye. In the Ex-Press group, a need for additional glaucoma surgery occurred due to high IOP in 12 eyes, and loss of light sensation developed in 1 eye.

Postoperative interventions

The postoperative intervention data are provided in Table 4. There was a significant difference in the proportion of the cases that underwent laser suture lysis between the two groups. Of the conventional group, 66.6% of the eyes needed laser suture lysis compared with the 84.1% in the Ex-Press group (p=0.0368). The number of sutured threads for scleral flap was significantly more in the conventional group (p<0.0001). The number of cut threads did not differ between both groups (p=0.297). The ratio of the suture lysis thread (number of cut threads/number of sutured threads) was significantly larger in the Ex-Press group (p<0.0001). The timing of the laser suture lysis of the first thread in the Ex-Press group was significantly sooner compared with that in the conventional group (p=0.0012).

Regarding needling, there was no significant difference in the proportion of cases that underwent needling, in the number of days post surgery until the needling, preoperative IOP, and postoperative IOP between two groups. There was no significant difference in needling results between the two groups after 1, 3, and 6 months. There were three cases (33.3%) in the conventional group and three cases (27.3%) in the Ex-Press group that were unable to control IOP after needling and required additional glaucoma surgery.

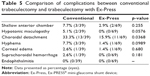

Complications

The postoperative complications of the two groups are summarized in Table 5. Shallow anterior chamber was clinically assessed under slit-lamp examination and was defined as iridocorneal touch in the periphery. Choroidal detachment causing hypotony was identified in 13 eyes (33.3%) in the conventional group, and in a significantly lower percentage in the larger Ex-Press group at 11 eyes (15.9%) (p=0.0368). In all cases, choroidal detachment disappeared spontaneously within 2 months. No significant intergroup difference was seen for other complications. There was one case of suprachoroidal hemorrhage in the conventional group. There was no case of endophthalmitis in either group.

Discussion

The mean postoperative IOP and the mean of number of glaucoma medications were not significantly different between the eyes that underwent a conventional trabeculectomy and the eyes that underwent a trabeculectomy with the use of an Ex-Press mini-tube shunt. The success rate was not significantly different between these groups. Our results agree with previous reports.4–13 Some studies reported that Ex-Press had fewer complications of early hypotony compared with trabeculectomy.2–6 In our study, the complications of choroidal detachment were less in the Ex-Press group. There are various reports on comparison between simultaneous cataract surgery (the Triple surgery) and the Single surgery.15–17 In our study, there was no significant difference in postoperative IOP, the number of medications, and the success rate. We compared the surgical results between POAG and PEXG. Some studies reported that PEXG has slightly poorer results.18,19 In our results, there was no significant difference; a larger study seems to be desirable.

Regarding postoperative interventions, the timing of the laser suture lysis of the first thread in the Ex-Press group was significantly sooner than that in the conventional group. As our investigation was a retrospective analysis of a limited number of glaucoma patients, this finding should be considered only a tendency. In fact, the timing of laser suture lysis varies depending on each case. In a trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press, the amount of aqueous humor exiting the bleb from the anterior chamber is limited, and thus, the Ex-Press has merit in that the risk of low IOP is small. However, with an Ex-Press, it is possible that the blebs might be smaller. In cases of a trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press, better results may be obtained by cutting the thread a little earlier than the timing of cutting the thread in a conventional trabeculectomy.

Laser suture lysis is useful for reducing the IOP, and it is essential for postoperative IOP management.20 Some reports indicated that surgery aiming for IOP <10 mmHg has good results.21,22 Early laser suture lysis is necessary to achieve lower and longer IOP control in trabeculectomy.23 Singh et al reported that laser suture lysis within 1 month (the median timing of suture lysis was 6 days) was safe and effective.20 Ralli et al reported that eyes not requiring laser suture lysis or eyes undergoing laser suture lysis ≤10 days after trabeculectomy were better results of long-term IOP control.24 There were few reports on the number of days of laser suture lysis after trabeculectomy with Ex-Press. Kato et al reported that 66.7% of patients were performed laser suture lysis within 1 week. In our study, all patients were performed laser suture lysis within 1 week in the Ex-Press group.7 The early application of laser suture lysis has a higher risk of hypotony.25 Hypotony might cause complications such as shallow anterior chamber, choroidal detachment, and hypotonic maculopathy. The most suitable timing for laser suture lysis is a very important factor affecting postoperative results.26 In our study, the mean of postoperative IOP was slightly lower than previous reports. Cutting the threads early might contribute for low postoperative IOP.

In our present study’s Ex-Press group, despite the small number of threads suturing the scleral flap at the intraoperative period and the short period to the laser suture lysis, the rate of low IOP was less than that seen in the conventional group. The cases who had cut all the threads were 23.1% in the conventional group and 58.6% in the Ex-Press group. Generally, it is easier to achieve low IOP with fewer sutures of the scleral flap and earlier laser suture lysis. In a trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press, the aqueous flow from the anterior chamber through the Ex-Press might be more controlled than that in a conventional trabeculectomy. For this reason, in eyes that undergo a trabeculectomy with the use of an Ex-Press, the risk of low IOP might be small. If postoperative management such as that used for a conventional trabeculectomy is conducted, the IOP might be higher.

Needling is useful for reducing the IOP for the management of bleb failure.27 Needling is often unnecessary if the intervention of laser suture lysis provides the successful control of the IOP. The results of needling in both groups seem to be comparable. Previous comparison reports that the proportion of the cases who required needling were 9.1%–30% in the conventional group and 4.8%–20.0% in the Ex-Press group.7,13

In our study, choroidal detachment occurred significantly more frequently in the conventional group compared with the Ex-Press group. The corresponding reported values are 11%–36% in the conventional group and 2%–20% in the Ex-Press group.12,13,28,29 The frequency of complications due to low IOP might differ depending on the target IOP. Our present findings are comparable to those of the above-cited studies. Choroidal detachment was transient in all cases, and no cases remained even after 2 months or more. Complications related to low IOP, shallow anterior chamber, and hypotonic maculopathy were also less frequent in our Ex-Press group, although the between-group difference was not significant. Trabeculectomy with Ex-Press might result in fewer complications of hypotony because the Ex-Press presents little risk of excessive filtration.

Netland et al reported that trabeculectomies with Ex-Press resulted in less hyphema than conventional trabeculectomy.6 In our study, there was no significant difference between the two groups. One of the reasons for this is that there was no case of neovascular glaucoma among our patients. Even with the Ex-Press, there are some cases of bleeding due to stabbing of the trabecular meshwork.

Our study has several limitations. The primary weaknesses are its retrospective, noncomparative design and our short follow-up period. The number of patients is small; a larger prospective comparative study is needed to fully investigate the periods up to laser suture lysis and the rates of postoperative complications. Postoperative follow-up period is significantly different. The selection of surgical methods was biased and could not be randomized. Our results might also have been affected by the learning curve involved in trabeculectomy surgery.

In conclusion, a trabeculectomy with an Ex-Press might require intentionally earlier laser suture lysis compared with the conventional trabeculectomy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sarkisian SR. The Ex-Press mini glaucoma shunt: technique and experience. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2009;16(3):134–137. | ||

Dahan E, Ben Simon GJ, Lafuma A. Comparison of trabeculectomy and Ex-PRESS implantation in fellow eyes of the same patient: a prospective, randomised study. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(5):703–710. | ||

Maris PJ Jr, Ishida K, Netland PA. Comparison of trabeculectomy with Ex-PRESS miniature glaucoma device implanted under scleral flap. J Glaucoma. 2007;16(1):14–19. | ||

Gallego-Pinazo R, Lopez-Sanchez E, Marin-Montiel J. [Postoperative outcomes after combined glaucoma surgery. Comparison of ex-press miniature implant with standard trabeculectomy]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2009;84(6):293–297. Spanish. | ||

Good TJ, Kahook MY. Assessment of bleb morphologic features and postoperative outcomes after Ex-PRESS drainage device implantation versus trabeculectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(3):507.e1–513.e1. | ||

Netland PA, Sarkisian SR Jr, Moster MR, et al. Randoized, prospective, comparative trial of EX-PRESS glaucoma filtration device versus trabeculectomy (XVT study). Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):433.e3–440.e3. | ||

Kato N, Takahashi G, Kumegawa K, Kabata Y, Tsuneoka H. Indications and postoperative treatment for Ex-PRESS(®) insertion in Japanese patients with glaucoma: comparison with standard trabeculectomy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1491–1498. | ||

Wagschal LD, Trope GE, Jinapriya D, Jin YP, Buys YM. Prospective randomized study comparing Ex-PRESS to trabeculectomy: 1-year results. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(8):624–629. | ||

de Jong LA. The Ex-PRESS glaucoma shunt versus trabeculectomy in open-angle glaucoma: a prospective randomized study. Adv Ther. 2009;26(3):336–345. | ||

Mendoza-Mendieta ME, Lopez-Venegas AP, Valdes-Casas G. Comparison between the EX-PRESS P-50 implant and trabeculectomy in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:269–276. | ||

Gonzalez-Rodriguez JM, Trope GE, Drori-Wagschal L, Jinapriya D, Buys YM. Comparison of trabeculectomy versus Ex-PRESS: 3-year follow-up. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(9):1269–1273. | ||

Lankaranian D, Razeghinejad MR, Prasad A, et al. Intermediate-term results of the Ex-PRESS miniature glaucoma implant under a scleral flap in previously operated eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39(5):421–428. | ||

Sugiyama T, Shibata M, Kojima S, Ueki M, Ikeda T. The first report on intermediate-term outcome of Ex-PRESS glaucoma filtration device implanted under scleral flap in Japanese patients. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1063–1066. | ||

Ares C, Kasner OP. Bleb needle redirection for the treatment of early postoperative trabeculectomy leaks: a novel approach. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43(2):225–228. | ||

Kleinmann G, Katz H, Pollack A, Schechtman E, Rachmiel R, Zalish M. Comparison of trabeculectomy with mitomycin C with or without phacoemulsification and lens implantation. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2002;33(2):102–108. | ||

Jung JL, Isida-Llerandi CG, Lazcano-Gomez G, SooHoo JR, Kahook MY. Intraocular pressure control after trabeculectomy, phacotrabeculectomy and phacoemulsification in a hispanic population. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2014;8(2):67–74. | ||

Takihara Y, Inatani M, Ogata-Iwao M, et al. Trabeculectomy for open-angle glaucoma in phakic eyes vs in pseudophakic eyes after phacoemulsification: a prospective clinical cohort study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(1):69–76. | ||

Lim SH, Cha SC. Long-term outcomes of Mitomycin-C trabeculectomy in exfoliative glaucoma versus primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2017;26(4):303–310. | ||

Fernández S, Pardiñas N, Laliena JL, et al. [Long-term tensional results after trabeculectomy. A comparative study among types of glaucoma and previous medical treatment]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2009;84(7):345–351. Spanish. | ||

Singh J, Bell RW, Adams A, O’Brien C. Enhancement of post trabeculectomy bleb formation by laser suture lysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(7):624–627. | ||

Iverson SM, Schultz SK, Shi W, Feuer WJ, Greenfield DS. Effectiveness of single-digit IOP targets on decreasing global and localized visual field progression after filtration surgery in eyes with progressive normal-tension glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(5):408–414. | ||

Aoyama Y, Murata H, Aihara M. Targeting a low-teen intraocular pressure by trabeculectomy with a fornix-based conjunctival flap: continuous Japanese case series by a single surgeon. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(3):225–232. | ||

Fukuchi T, Ueda J, Yaoeda K, Suda K, Seki M, Abe H. The outcome of mitomycin C trabeculectomy and laser suture lysis depends on postoperative management. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2006;50(5):455–459. | ||

Ralli M, Nouri-Mahdavi K, Caprioli J. Outcomes of laser suture lysis after initial trabeculectomy with adjunctive mitomycin C. J Glaucoma. 2006;15(1):60–67. | ||

Bardak Y, Cuypers MH, Tilanus MA, Eggink CA. Ocular hypotony after laser suture lysis following trabeculectomy with mitomycin C. Int Ophthalmol. 1997;21(6):325–330. | ||

Cho HK, Kojima S, Inoue T, Fukushima A, Kee C, Tanihara H. Effect of laser suture lysis on filtration openings: a prospective three-dimensional anterior segment optical coherence tomography study. Eye (Lond). 2015;29(9):1220–1225. | ||

Ghoneim EM, Abd El Hameed M. Needling augmented with topical application of mitomycin C for management of bleb failure. J Glaucoma. 2011;20(8):528–532. | ||

Kuroda U, Inoue T, Awai-Kasaoka N, Shobayashi K, Kojima S, Tanihara H. Fornix-based versus limbal-based conjunctival flaps in trabeculectomy with mitomycin C in high-risk patients. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:949–954. | ||

De Feo F, Bagnis A, Bricola G, Scotto R, Traverso CE. Efficacy and safety of a steel drainage device implanted under a scleral flap. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44(4):457–462. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.