Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 12

A systematic review of questionnaires about patient’s values and preferences in clinical practice guidelines

Authors Bai F, Ling J, Esoimeme G, Yao L, Wang M, Huang J, Shi A , Cao Z, Chen Y, Tian J, Wang X , Yang K

Received 19 June 2018

Accepted for publication 17 August 2018

Published 2 November 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 2309—2323

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S177540

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Naifeng Liu

Fei Bai,1–4,* Juan Ling,1–3,* Gloria Esoimeme,5 Liang Yao,1–3 Mingxia Wang,1,6 Jiajun Huang,1,7 Anchen Shi,1,6 Zehui Cao,1,7 Yaolong Chen,1–3 Jinhui Tian,1–3 Xiaoqin Wang,1–3 Kehu Yang1–3

1Evidence-Based Medicine Center, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China; 2Key Laboratory of Evidence-Based Medicine and Knowledge Translation of Gansu Province, Lanzhou, China; 3WHO Collaborating Center for Guideline Implementation and Knowledge Translation, Lanzhou 730000, China; 4National Center for Medical Administration Service, Beijing, China; 5University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Columbia, SC, USA; 6The Second Clinical Medical College of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China; 7The First Clinical Medical College of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

*These authors contributed equally in this work

Objective: We conducted a systematic review to evaluate questionnaires about patient’s values and preferences to provide information on the most appropriate questionnaires to be used when developing clinical practice guidelines.

Methods: A systematic literature search of the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Chinese Biomedical Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and the Wanfang Database was performed to identify studies on questionnaires evaluating patient’s values and preferences. The articles that used fully structured questionnaires or scales with standardized questions and answer options were included. We assessed the questionnaires’ construction and content with a psychometric methodology and summarized the domains and items about patient’s preferences and values.

Results: A total of 7,008 records were retrieved by the search strategy and scanned, and 20 articles were finally included. Of these, 10 (50%) articles described the process of item generation and only four questionnaires (20%, 4/20) mentioned the pilot testing. Regarding “validity”, seven questionnaires (35%, 7/20) assessed validity and only one (5%, 1/20) questionnaire assessed internal consistency, with Cornbrash’s α values of 0.74–0.87. For “acceptability”, the time to complete the questionnaires ranged from 10 to 30 minutes and only nine studies (45%, 9/20) reported the response rates. In addition, the results of domains and items about patient’s preferences and values showed that the “effectiveness” domain was the most considered item in the patient’s value questionnaire followed by “safety”, “prognosis”, and others, whereas the least considered domain was “physician’s experience”.

Conclusion: Only a few studies have developed questionnaires with rigorous psychometric methods to measure patient’s preferences and values. Currently, still there is no valid or reliable questionnaire for patient’s preferences and values for use when developing clinical practice guidelines. Further study should be conducted to develop standardized instruments to measure patient’s preferences and values. This study provides the domains and items that may be used in formulating questionnaires about patient’s preferences and values.

Keywords: questionnaires, guideline, patient’s values and preferences, systematic review, Patient Satisfaction

Introduction

Over the last century, there have been several medical innovations offering multiple viable treatment options for most diseases. In addition, increasing patient’s awareness and autonomy have made it necessary to consider patient’s preferences and values in the treatment decision-making process.1 Patient’s preference refers to a patient’s perspective, expectations, and goals for health, as well as the processes involved in evaluating the potential benefits, harms, and costs of each management option offered to the patient.2 Patient’s value refers to the benefit that a patient assigns to a given treatment option.3 Health care policymakers recommend that the patient’s preferences should be considered through active involvement of patient in the treatment decision-making process.4–7 The National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine),8 the Guidelines International Network,9 and Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II)10 all recommend incorporating patient’s values in the development of clinical practice guidelines. A clinical practice guideline that does not consider patient’s preferences may provide recommendations that are not optimal or consistent with patient’s preferences or values.11 For example, the US Preventive Service Task Force clinical practice guideline recommends that the prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer should be patient specific, providing room for the patient’s values and preferences to be incorporated in the clinical decision-making process.12

There are several methods to determine patient’s preferences, including questionnaires, interviews, and discrete choice experiments.13 Herein, we examined the use of questionnaires to obtain patient’s preferences and values. Questionnaires are an important tool to survey attitudes, knowledge, and practice;14,15 to generate or refine research questions; and to evaluate the impact of clinical research in practice. Questionnaires can use a descriptive qualitative method16 to report factual data or an explanatory method17 to draw inferences and relationships between constructs or concepts. The development of patient’s preference questionnaires should be performed ideally through a psychometric approach, ensuring item generation, pretest and pilot testing,18 validity,19 reliability testing,20 and acceptability21 in measuring patient’s preferences and values. However, there are many factors that influence the formulation and implementation of questionnaires, including its contents, mode of administration, number of questions, time to complete, the setting of the questions, and ease of understanding.

To contribute to the development of optimal methods to design and conduct questionnaires in primary studies on patient’s values and preferences, we conducted a systematic review to summarize characteristics of studies and assessed the quality of the development of questionnaires used to assess patient’s preferences. Our findings will help researchers to identify the most appropriate questionnaires to use when retrieving information on patient’s preferences and values in different clinical scenarios.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

An electronic literature search of the MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, Chinese Biomedical Database (which is considered as an equivalent of MEDLINE in China and only contains studies published in Chinese), China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wan Fang databases was performed, from their inception to January 2018. In addition, hand searches were accomplished in Google from the reference lists of included articles. The search was run using free-text terms and medical subject headings; the search strategy is available as supplementary material.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they 1) focused on patient’s preferences and/or values and 2) included fully structured questionnaires or scales with standardized questions and answer options that were patient (self-) reported. Studies were excluded if 1) they contained incomplete questionnaires of diseases focused on patient’s preferences and/or values; 2) the questionnaires reported a rating by an interviewer; or 3) they were published in a language other than Chinese or English.

Study selection

The study selection process was piloted by two independent reviewers at the beginning of the review. All titles, abstracts, and full articles were independently reviewed by more than two reviewers, and the full-text articles of relevant studies were obtained. Disagreements between the reviewers were initially resolved by consensus and when necessary by a third reviewer.

Data extraction

We developed and piloted a data extraction form to extract the data. The following information was extracted: 1) characteristics of the studies, such as the disease domain, research type, study duration, setting, patient characteristics, and the method used to calculate sample size; 2) characteristics of the questionnaires (ie, mode of administration, item generation, pilot testing, time to complete, response rates, the number of items, the setting of questions, response options, and incentive offered to respondents); and 3) the data related to conduct questionnaires (item and dimension generation, pretest and pilot testing, validity, reliability testing, and acceptability).

We abstracted the content relevant to patient’s preferences into the data extraction form. After discussing and sorting discrepancies related to wording or interpretations, we summarized the domains and items about patient’s preferences. Two authors (JL and FB) independently extracted the data from the questionnaires. Disagreements were initially resolved by consensus and when necessary with the help of a third reviewer (K-HY).

Data analysis and assessment

Two independent reviewers psychometrically assessed the identified questionnaires, determining how items and dimensions were generated and if pretests and pilot testing of the questionnaires were performed for reliability, validity, and acceptability.22–25 These items were judged as follows: “yes” (when the criterion was explicitly met), “no” (when the criterion was explicitly not met), “uncertain” (when the item was relevant but not described completely), and “not applicable”. Table 1 shows the details of the psychometric properties assessed. Apart from assessing the quality of the questionnaires, we used descriptive statistics to analyze the extracted data and calculated absolute frequencies and proportions for all items.

| Table 1 Items of the psychometric methods |

Results

Study selection

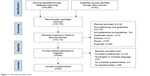

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study selection and identification process. The electronic database search produced 6,956 references, and 52 additional references were identified through other sources. A total of 7,008 records were identified by removing duplicates after the title and abstract screening, excluding 4,974 records, and resulting in 187 articles for full-text assessment. Of these, 21 articles were excluded because they were not specific to patient’s preferences and 106 articles were excluded because they had no questionnaires. In addition, seven articles were excluded because the questionnaires were incomplete. Finally, 20 articles that had complete questionnaires focusing on patient’s preferences were included.

| Figure 1 Trial selection flow chart. |

Characteristics of included studies

The final sample included 20 articles in English, published between 1999 and 2017, with study duration ranging from 2 to 20 months, including a total patient sample size of 6,300 (Table 2). Table 2 shows the included study characteristics. Six (30%) of these studies were related to cancer diseases,30,33,37,43,46,47 and 15 (75%) were conducted in the outpatient department. Furthermore, nine (45%) studies did not report the study design,30,34,38,40,41,43,44,46 12 (60%) studies provided training to the study participants,32–38,40,41,45,47,49 while four (20%) studies did not report information about patient training.42–44,48 In addition, only five (25%) studies provided the method used to calculate the sample size35–39,39–42,42–47 and only six (30%) studies investigated patient’s family members.31,34–37,49 Finally, 17 (85%) studies provided information assessing patient knowledge and beliefs.30,32–35,37–45,47–49

Characteristics of questionnaires in the included studies

The characteristics of questionnaires in the included studies are listed in Table 3.

Most questionnaires were found to be easy to administer; 16 questionnaires (80%) were conducted through an interview survey,31–40,43–47,49 whereas only one questionnaire (5%) was conducted via an online survey;48 three questionnaires (15%) did not report the method used for survey administration.30,41,42 The mean number of pages per questionnaire was 4.4 (range, 1–17), the mean number of items per questionnaire was 14 (range, 2–50), and 16 (80%) questionnaires were filled anonymously.30,32–42,44,45,47–49 Further, 16 studies (80%) obtained informed consent from the patients before the study,30,31,33,34,44–49 whereas four studies (20%) did not report if informed consent had been obtained.32,35,42,43 Most questionnaires used 4- to 7-point scales of measurement. The single-choice question format with open-ended questions and a choice task was the most common type of survey setting (25%), followed by single-choice questions with a choice task (33%). In addition, two studies33,47 (10%) reported that they used a patient incentive during the survey, of which one study33 reported that respondents were provided with a barcode to initiate payment of $1.00 and another study47 reported compensation of respondents with a $15 gift card.

Questionnaire content evaluation

The evaluation of contents of questionnaire is summarized in Table 4.

| Table 4 The evaluation of components of questionnaires |

From the included studies, 10 (50%) described the process of item generation.33,35,36,38,39,41,42,44–46 As for pretest and pilot testing, only four questionnaires (20%) mentioned that the survey had undergone cognitive pretesting or pilot testing.33,35,39,44 Regarding validity, seven questionnaires (35%) assessed validity by asking patients if there were other aspects of care that were not mentioned in the questionnaires,34–36,42–44 whereas only one questionnaire (5%) assessed internal consistency using Cronbach’s α with values of 0.74–0.87.43 For acceptability, the time to complete the questionnaires ranged from 10 to 30 minutes, with nine studies (45%) reporting such data.35,36,38,40,42,43,47,48 Furthermore, response rates of the questionnaires exceeded 50% as reported by 10 studies.31,33–,35,,38,40,42–44,46 In addition, only two studies showed the highest questionnaire content quality following psychometric analysis;35,44 four studies did not follow the psychometric methods to use the questionnaire measuring patient’s preferences and values since neither did they describe item generation and pilot testing nor did they report the related information of validity, reliability, and acceptability.30,32,37,49

Items and domains identified for measuring patient’s preferences

Table 5 presents a list of domains and examples of items about patient’s preferences and values in the questionnaires reviewed. We identified the items that measured patient’s values and preferences and grouped them into four domains, namely effectiveness, safety, prognosis, and others. The “others” domain included information on cost, physician’s experience, physician’s recommendation, and initiation of the decision-making process. Some domains and items were more frequently reported than others. For example, the “effectiveness” domain was the most considered in the patient’s value questionnaire (36.4%, 12/33), while the least considered domain was “physician’s experience” (3.03%, 1/33).

Discussion

The present study reviews the content and construction of questionnaires to provide information on the most appropriate questionnaires to assess patient’s preferences and values for the development of clinical practice guidelines. Our survey of the literature showed that few questionnaires met the psychometric methodology, resulting in a low quality of content and construction of questionnaires, and that even fewer studies reported the method used to calculate the sample size. These results emphasize the importance of having a standard method available to design and conduct questionnaires to survey patient’s preferences and values. Future research should follow the psychometric methodology to develop questionnaires measuring patient’s preferences and values, including the main steps of item generation, pretesting or pilot testing of the initial questionnaire, and testing of the final version of the questionnaire for content validity, reliability, and acceptability. In addition, ethics statements50 of questionnaires (referring to informed consent) should be described as “written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to study participation” or “written consent was obtained prior to initiating the survey”.

Another issue identified in our systematic review was that domains and items regarding patient’s preferences and values should consider effectiveness, safety, prognosis, and other factors into the formulation of patient’s value and preference questionnaires.

Effectiveness

Treatment effectiveness is the most considered aspect by patients. The effectiveness domain included questions on the convenience of the treatment option, the frequency of testing, the types of drug preparations, the benefit of the intervention, treatment time, and frequency of drug administration. The benefit of the intervention was the most important factor for the majority of patients in the domain of effectiveness, followed by the convenience of the treatment option, hospital length of stay, and frequency of testing. Medication route, types of drug preparations, frequency of drug administration, and duration of treatment are important considerations when evaluating patient’s preferences. These factors should be considered when designing items for patient’s preference and value questionnaires.

Safety

The safety domain includes adverse effects, complications from interventions, and the risk of disease transmission. The risk of complications and communicating the risk of the interventions were the most important factors for the majority of patients in the domain of safety, followed by the risk of adverse effects and disease transmission. The majority of treatment options are accompanied by adverse effects, including infection, bleeding, pain, and, at the extreme, death.50–53 Therefore, when developing questionnaires to measure patient’s values and preferences, it is important to include questions on treatment safety, so that patients can make an informed decision regarding their preferred treatment. For example, Rid et al35 measured safety by asking “when your physician communicates with you about medical risk (that is, the chance or come will occur related to a probability of adverse effects and complications with specific medical intervention you are considering), which treatment would you prefer?”

Prognosis

Prognosis includes the risk of relapse and the likelihood of a return to normal health following treatment. Our study recommends a detailed display of information on prognosis when formulating such questionnaires. For example, statements such as “we will ask you to think about how you would feel about these different treatments, you will be given detailed information about three treatment options that differ in terms of the risk of relapse, recovery time, and the chance of returning to normal health after treatment, which treatment would you prefer?” should be presented. In summary, all diseases and their paths vary, and patients have varying emotions, values, and preferences; therefore, prognosis factors should be considered to make more valid questionnaires on patient’s values and preferences.54

Others

The “others” domain included cost, physician’s experience, physician’s recommendation, and initiation of the decision-making process. The results showed that the financial cost or financial burden of treatment accounts for a large proportion of the questionnaire items affecting patient’s values and preferences when considering treatment choice. Questionnaire developers could display the medical expenses for alternative treatments in detail to fully capture the factors influencing patient’s preferences with regards to cost. In addition, the physician’s recommendation and experience should be considered in the development of questionnaires on patient’s preferences.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to conduct a systematic review evaluating questionnaires measuring patient’s values and preferences. The results herein will provide valuable guidance to researchers and policymakers during the development of clinical practice guidelines and in the shared clinical decision-making process. The strengths of our study include explicit eligibility criteria, a comprehensive literature search, duplicate assessment of eligibility with a high agreement, and a detailed iterative process for the identification of items suggested in the reviews and categorization of items into domains.

Nevertheless, it also has several limitations. First, only studies published in English were included. Second, although we finally identified 20 complete questionnaires, it is possible that we failed to identify other eligible questionnaires due to varying terminology and suboptimal indexing of patient’s preferences.

Conclusion

Only a few studies have developed questionnaires with rigorous psychometric methods to measure patient’s preferences and values, and there are still no valid or reliable questionnaires to do this in the process of treatment decision making and for the development of clinical practice guidelines.

Abbreviations

AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II; NR, not reported; ACL, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; SCQ, single-choice question; OeQ, subjective question; MCQ, multiple-choice question.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the library of Lanzhou University for their database in accessing and acquiring the full texts. This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (8167140308).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Evidence McClellan MB, McGinnis JM, Nabel EJ, Olsen LM. Based Medicine and the Changing Nature of Healthcare. In: IOM Annual Meeting Summary; 2007. | ||

Montori VM, Devereaux PJ, Straus S, Haynes B, Guyatt G. Chapter 22.2. Decision making and the patient. In: Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ, editors. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. In: Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill Education; 2008. | ||

Lang E, Bell NR, Dickinson JA, et al. Eliciting patient values and preferences to inform shared decision making in preventive screening. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(1):28–31. | ||

Boivin A, Currie K, Fervers B, et al. Patient and public involvement in clinical guidelines: international experiences and future perspectives. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5):e22. | ||

Verkerk K, van Veenendaal H, Severens JL, Hendriks EJ, Burgers JS. Considered judgement in evidence-based guideline development. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(5):365–369. | ||

Murphy JF. Paternalism or partnership: clinical practice guidelines and patient preferences. Ir Med J. 2008;101(8):232. | ||

Krahn M, Naglie G. The next step in guideline development: incorporating patient preferences. JAMA. 2008;300(4):436–438. | ||

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Port J Nephrol Hypert. 2011;110–275. | ||

Working Groups/G-I-N PUBLIC [webpage on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.g-i-n.net/working-groups/gin-public/toolkit. Accessed January 3, 2018. | ||

Agree Collaboration [web page on the Internet]. Appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation. Available from: https://www.agreetrust.org/. Accessed January 3, 2018. | ||

Owens DK. Spine update. Patient preferences and the development of practice guidelines. Spine. 1998;23(9):1073–1079. | ||

Medicine I O. Evidence-Based Medicine and the Changing Nature of Healthcare: 2007 IOM Annual Meeting Summary[J]. National Academies Press, 2008;20(3):327–329. | ||

Lagarde M, Blaauw D. A review of the application and contribution of discrete choice experiments to inform human resources policy interventions. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(1):1–10. | ||

Passmore C, Dobbie AE, Parchman M. Guidelines for constructing a survey. Fam Med. 2002;34:281–286. | ||

Rubenfeld GD. Surveys: an introduction. Respir Care. 2004;49:1181–1185. | ||

Colorafi KJ, Evans B. Qualitative Descriptive Methods in Health Science Research. HERD. 2016;9(4):16–25. | ||

Thoma A, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Users’ guide to the surgical literature. Can J Surg. 2012;55(3):207–211. | ||

Chaudhary AK, Israel GD. The Savvy Survey #8: Pilot Testing and Pretesting Questionnaires. Agricultural Education & Communication; Florida; University of Florida 2018. | ||

Wan CH, Meng Q, Yang Z, et al. Development of the general module of the system of quality of life instruments for cancer patients: reliability and validity analysis. Ai Zheng. 2007;26(3):225–229. | ||

Singh AS, Vik FN, Chinapaw MJ, et al. Test-retest reliability and construct validity of the ENERGY-child questionnaire on energy balance-related behaviours and their potential determinants: the ENERGY-project. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;9;8:136. | ||

Hunsley J. Development of the Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1992;14(1):55–64. | ||

Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(14):i–iv, 1–74. | ||

Fung D, Cohen MM. Measuring patient satisfaction with anesthesia care: a review of current methodology. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(5):1089–1098. | ||

Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide To Their Development and Use. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003:4–14. | ||

Bowling A. Handbook of Health Research Methods: Investigation, Measurement and Analysis. 3rd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005:394–427. | ||

Niero M, Martin M, Finger T, et al. A new approach to multicultural item generation in the development of two obesity-specific measures: the Obesity and Weight Loss Quality of Life (OWLQOL) questionnaire and the Weight-Related Symptom Measure (WRSM). Clin Ther. 2002;24(4):690–700. | ||

Hewitt MR. DELPHI Survey. Leading Edge. 2002;2(6):18–31. | ||

Cella DF, Lloyd SR. Wright BD. Cultural instrument equating: Current research and future directions. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of Life and Pharmacoeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996:707–715. | ||

Babbie ER. Survey Research Methods. 2nd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co Inc; 1990:257–318. | ||

Bo Y, Fang Z, Zong Z. Preferences for treatment of lobectomy in Chinese lung cancer patients: video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or open thoracotomy? Patient Preference Adher. 2014;8(8):1393–1397. | ||

Welsh P, Tiffin PA. Assessing adolescent preference in the treatment of first-episode psychosis and psychosis risk. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014;8(3):281–285. | ||

Vu HT, Sayuk GS, Gupta N, Hollander T, Kim A, Early DS. Patient preferences of a resect and discard paradigm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(2):381–384. | ||

Tong BC, Wallace S, Hartwig MG, D’Amico TA, Huber JC. Patient Preferences in Treatment Choices for Early-Stage Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(6):1837–1844. | ||

Sekimoto M, Asai A, Ohnishi M, et al. Patients’ preferences for involvement in treatment decision making in Japan. BMC Fam Pract. 2004;5(1):1–10. | ||

Rid A, Wesley R, Pavlick M, Maynard S, Roth K, Wendler D. Patients’ priorities for treatment decision making during periods of incapacity: quantitative survey. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(5):1165–1183. | ||

Noble S, Matzdorff A, Maraveyas A, Holm MV, Pisa G. Assessing patients’ anticoagulation preferences for the treatment of cancer-associated thrombosis using conjoint methodology. Haematologica. 2015;100(11):1486–1492. | ||

Mazur DJ, Hickam DH, Mazur MD. How patients’ preferences for risk information influence treatment choice in a case of high risk and high therapeutic uncertainty: asymptomatic localized prostate cancer. Med Decis Making. 1999;19(4):394–398. | ||

Matti AI, Keane MC, McCarl H, Klaer P, Chen CS. Patients’ knowledge and perception on optic neuritis management before and after an information session. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010;10(1):7. | ||

Maciver J, Tibbles A, Billia F, Ross H. Patient perceptions of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator deactivation discussions: A qualitative study. SAGE Open Med. 2016;4:205031211664269. | ||

Sanford D, Kyle R, Lazo-Langner A, et al. Patient preferences for stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Oncol. 2014;21(2):241–249. | ||

Koh HS, In Y, Kong CG, Won HY, Kim KH, Lee JH. Factors affecting patients’ graft choice in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(2):69–75. | ||

Ha V, McDonald SD. Pregnant women’s preferences for and concerns about preterm birth prevention: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):49. | ||

Gareen IF, Siewert B, Vanness DJ, Herman B, Johnson CD, Gatsonis C. Patient willingness for repeat screening and preference for CT colonography and optical colonoscopy in ACRIN 6664: the National CT Colonography trial. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9(2):1043. | ||

Fiks AG, Mayne S, Debartolo E, Power TJ, Guevara JP. Parental preferences and goals regarding ADHD treatment. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):692–702. | ||

Eckman MH, Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt GH, et al. Women’s values and preferences for thromboprophylaxis during pregnancy: a comparison of direct-choice and decision analysis using patient specific utilities. Thromb Res. 2015;136(2):341–347. | ||

Choudhry A, Hong J, Chong K, et al. Patients’ preferences for biopsy result notification in an era of electronic messaging methods. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(5):513. | ||

Calderwood AH, Wasan SK, Heeren TC, Schroy PC. Patient and Provider Preferences for Colorectal Cancer Screening: How Does CT Colonography Compare to Other Modalities? Int J Canc Prev. 2011;4(4):307–338. | ||

Bolge SC, Goren A, Brown D, Ginsberg S, Allen I. Openness to and preference for attributes of biologic therapy prior to initiation among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: patient and rheumatologist perspectives and implications for decision making. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1079–1090. | ||

Hofman P, Lilleøre SK, Ter-Borch G. Needle with a novel attachment versus conventional screw-thread needles: a preference and ease-of-use test among children and adolescents with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5(6):1480–1487. | ||

Ki EJ, Choi HL, Lee J. Does Ethics Statement of a Public Relations Firm Make a Difference? Yes it Does!! J Bus Ethics. 2012;105(2):267–276. | ||

Chowdhury R, Abbas A, Idriz S, Hoy A, Rutherford EE, Smart JM. Should warfarin or aspirin be stopped prior to prostate biopsy? An analysis of bleeding complications related to increasing sample number regimes. Clin Radiol. 2012;67(12):e64–e70. | ||

Jirkof P. Side effects of pain and analgesia in animal experimentation. Lab Anim. 2017;46(4):123–128. | ||

Hicks JM, Singla A, Shen FH, Arlet V. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in scoliosis surgery: a systematic review. Spine. 2010;35(11):E465. | ||

Lang E, Bell NR, Dickinson JA. Eliciting patient values and preferences to inform shared decision making in preventive screening. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(1):10–11. |

Supplementary material

Search strategies.

Search strategies (take PubMed as an example):

#1 Search “Guidelines as Topic” [Mesh]

#2 Search “Practice Guidelines as Topic” [Mesh]

#3 Search “Guideline” [Publication Type]

#4 Search (((((guideline* [Title/Abstract]) OR consensus [Title/Abstract]) OR instruction[Title/Abstract]) OR routine [Title/Abstract]) OR “clinical practice” [Title/Abstract]) OR “recommendation*” [Title/Abstract])))))

#5 Search #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4

#6 Search “Patient Preference” [Mesh]

#7 Search patient preference* [Title/Abstract]

#8 Search #6 OR #7

#9 Search “Patient Satisfaction” [Mesh]

#10 Search Patient* Satisfaction [Title/Abstract]

#11 Search #9 OR #10

#12 Search “Attitude to Health” [Mesh]

#13 Search (attitude to health [Title/Abstract]) OR health attitude* [Title/Abstract]

#14 Search #12 OR #13

#15 Search “Treatment Adherence and Compliance” [Mesh]

#16 Search (adherence [Title/Abstract] AND compliance [Title/Abstract])

#17 Search #15 OR #16

#18 Search patient decision [Title/Abstract]

#19 Search patient acceptance [Title/Abstract]

#20 Search “Patient Acceptance of Health Care” [Mesh]

#21 Search #19 OR #20

#22 Search patient perspective [Title/Abstract]

#23 Search health state utilit* [Title/Abstract]

#24 Search #8 OR #11 OR #14 OR #17 OR #18 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23

#25 Search #5 AND #24

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.