Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 10

A phenomenological study on resilience of the elderly suffering from chronic disease: a qualitative study

Authors Hassani P, Izadi-Avanji FS, Rakhshan M , Alavi Majd H

Received 2 September 2016

Accepted for publication 14 November 2016

Published 7 February 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 59—67

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S121336

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Parkhide Hassani,1 Fatemeh-Sadat Izadi-Avanji,2 Mahnaz Rakhshan,3 Hamid Alavi Majd4

1Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 2Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, International Branch of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 3Community Based Psychiatric Care Research Center, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran; 4Department of Biostatistics, Facility of Paramedical, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Background: Resilience is a key factor in improving health and attenuating problems caused by chronic diseases in the elderly. Having a clear understanding of its meaning in a specific population can be of great help in taking efficient steps toward better health services. Given the lack of information in this regard, the aim of this study was to understand the meaning of resilience for hospitalized older people who experience chronic conditions.

Methods: The study was carried out as a qualitative work based on a descriptive phenomenological approach. The participants were selected purposefully, so that 22 elderly with chronic disease were interviewed in 24 sessions. The collected data were recorded and analyzed through Colaizzi’s method.

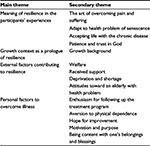

Results: Four themes were extracted from the interviews as follows: 1) “meaning of resilience in the participants’ experiences” with subthemes of “the art of overcoming pain and suffering”, “adapt to health problem of senescence”, “accepting life with the chronic disease”, and “patience and trust in God”; 2) “growth context as a prologue of resilience” with subthemes of “growth background”; 3) “external factors contributing to resilience” with subthemes of “welfare”, “received support”, “deprivation and shortage”, and “attitudes toward an elderly with health problem”; and 4) “personal factors to overcome illness” with subthemes of “enthusiasm for following up the treatment program”, “aversion to physical dependence”, “hope for improvement”, “motivation and purpose”, and “being content with one’s belongings and blessings”.

Conclusion: Improvement in resilience is associated with a patient-oriented approach. Providers of health services might make proper interventions based on unique needs of patients to improve their resilience and ability to overcome health problems. This can be performed by family members, health team, and related organizations and bodies.

Keywords: chronic disease, resilience, aged, qualitative studies

Introduction

Resilience is a relatively new psychological construct in geriatrics that allows older adults to improve the ability to adapt positively when faced with adversity.1 Resilience has an important role in recovery from adversity and better physical and mental health in later life.2 With increased age, physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning may decrease;3 in addition, there are an increasing number of older adults suffering from chronic illness.4 Some of the negative effects of life with chronic diseases are decrease in physical performance, decrease in pain tolerance, potential decrease in life expectation, and psychological threats such as feeling seclusion, loss of self-confidence, and changes in social roles.5,6 Despite the increase in health problems in aging, most of the elderly tend to adapt to their situation.7 Taking into account that having a successful senescence process needs the ability to adapt to the health problems, many studies have tried to determine the factors predicting positive response to negative events of life, and among them resilience is notable.8 Resilience is a dynamic process through which people develop a sense of regaining well-being despite all challenges.9 According to the interviews with the elderly, resilience is the sense of being relevant, independent, and meaningful.10 Experience of the elderly who has received long-term health care indicates that the main sources of resilience were constituted on three domains of individual, interactional and contextual.11 Experiences of the elderly suffering from cancer have indicated that social support and spirituality were the main factors in resilience.12

Along with the hardships of chronic diseases, the elderly usually encounter emotional stressors such as losing their spouses and loved ones; this makes it essential to have a clear understating of the meaning of resilience. Through the understanding of the meaning of resilience and its structure, resources of resilience can be identified. Resources that can contribute to growth and fostering of resilience may help nurses to promote a positive adaptation toward successful aging.13 Enhanced resilience helps older people to manage the negative impact of changes in health13 and may enable them to become more independent.14 Health care providers need to have a clear understanding of resilience based on humans’ experiences in the specific context of their society. Therefore, the aim of this study was to understand the meaning of resilience and its structure for hospitalized older people who experience chronic conditions.

Methods

A qualitative study based on descriptive phenomenological approach was carried out. Descriptive phenomenological approach is one of the best approaches to describe the experience of resilience in the elderly suffering from chronic diseases. The approach focuses on how people experience a phenomenon and its essence.15 The main question that the authors try to find an answer is the nature and meaning of resilience as perceived by the patients suffering from chronic diseases.

Colaizzi describes nine steps for directing a descriptive phenomenological study. These activities are as follows: describing the phenomenon, collecting descriptions of the subjects, reading the interviews repeatedly, extracting significant statements from the data, clarifying the meaning of each statement, categorizing the meaning of significant statements, providing a comprehensive description, referring to the participants for validating the descriptions, and revising the findings in the validation step.16 Inclusion criteria were as follows: age of at least 65 years, having at least one chronic disease diagnosed by a specialist physician, willingness to express feelings pertinent to the subject of the study, ability to express rich experiences, and no psychological and cognitive disorders.

Data gathering

At the first step, the researchers identified the elderly’s experiences and beliefs about the concept of resilience to avoid any biased interpretation of the findings. In-depth, semi-structured, and face-to-face interviews were used for data collection. In this study, purposeful sampling was utilized for the recruitment of 22 participants. Participants were selected among hospitalized older adults suffering from chronic conditions in a hospital located in Kashan, Iran. The hospital under study is the main provider of health services to the older adults. Our research environment constituted four surgery wards, four internal wards, one infectious ward, and one cardiovascular care unit. Researchers randomly chose the first ward. Then, referring to the ward, the first patient who had inclusion criteria enrolled in the study and an interview was done. Next, the participants were chosen according to the medical and non-repetitive patients’ health condition.

The researcher met the candidates at the hospital and briefed them about the necessity and purpose of the study before making an appointment for the interview. The patient’s permission for recording their voice was also obtained. The interviews were performed privately in the ward physician’s office, and some interviews were performed at the patient’s house when the patients returned home from the hospital. Interview with four patients was performed in two parts due to tiredness of the patient. Data gathering was continued until the new code was not added to the previous code. Finally, after interviews with 22 patients, data saturation was achieved.

Throughout the interviews, the following open-ended questions were asked: “tell me about some of the problems you have due to your chronic conditions”, “what does resilience mean based on your experiences?”, and “what factors increase or decrease your resilience?” To motivate the participants to share deeper information, probing questions were also asked, such as “tell me more”, “what do you mean exactly?”, or “give me an example”. With the permission of the participants, the interviews were recorded digitally, and then the whole interviews were transcribed word by word.

Data analyses

Steps three to nine of Colaizzi’s analysis method are about data analyses. Immediately after conducting each interview, the researcher actively listened to each of the participants’ audio recording for several times and made a verbatim transcription of it. This activity was performed to gain a sense of the participants’ descriptions of their experience in understanding the meaning of resilience.

In the next step, 767 significant statements and phrases related to meaning and structure of resilience were extracted and coded. All the statements were reviewed by the researcher and researcher’s supervisor to ensure that the extracted statements reflect the objectives of the study. After extracting the statements and phrases, the core meaning of the statements was collected. Afterward, the formulated meanings were categorized into 37 theme clusters. Then, groups of theme clusters that reflect a viewpoint issue were added together to form themes. Accordingly, the eight themes were emerged. Finally, the theme clusters and themes were compared with each other and reorganized into four themes and 13 subthemes.

For providing a comprehensive description, the researcher used the notes that were made while analyzing interview transcripts to provide written descriptions and explanations about participants’ experiences and also to write phenomenological texts that represented the findings. Quotations from the participants were also used while writing the descriptions and the explanations.

The next step was to refer to the participants for validating the descriptions. In this step, summary of the interview and the generated themes were provided to the participants who were randomly selected, and they were asked to validate their experiences. In the final step, the participants’ comments were included in the final report of the findings.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness of findings was enhanced using Lincoln and Guba’s17 criteria: credibility, dependability, and conformability.

With regard to credibility, data were coded by a supervisor independently, and the result was compared with that by the author. In addition, the results of the analyses were provided to the participants for confirmation and modification if needed. Moreover, the study was carried out by a team under supervision of experts, so that credibility of the data was guaranteed. With regard to dependability, the interviews’ text and the extracted codes were provided to two experts of qualitative studies for further examination. To ensure transferability of the data and to increase relevance of the data and environment of the study, the authors collected more details about the participants (Table 1). By suspending their prior ideas while extracting themes from the descriptions of the participants, the researchers reinforced the conformability of the study. To guarantee dependability, all the documents were kept available throughout the study, the collected data were deeply examined, and an adequate number of participants were interviewed.

| Table 1 Specifications of the participants in the study Note: an, number of participants. Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BA, bachelor of arts; MSc, master of science. |

Ethical considerations

The hospital under study was affiliated with Kashan Medical Science University; therefore, the study was needed to be and was approved by the ethics committee of the university (No: P/29/5/1/3425). Before the interview, the participants were informed about the purposes and necessity of the study, and all of them expressed consent for participation. Taking notes and recording the interview were also performed after obtaining permission from the participants. The participants were ensured that confidentiality of their information will be maintained throughout and after the study. They were also informed that they can leave the study at any time (none left the study).

Finding

A total of 22 participants met the inclusion criteria and took part in the study. Specifications of the participants are listed in Table 1.

Based on the data analyses, four main themes were extracted from the interviews including: “meaning of resilience in the participants’ experiences”, “growth context as a prologue of resilience”, “external factors contributing to resilience”, and “personal factors to overcome illness” (Table 2).

| Table 2 Main theme and secondary themes |

Theme one: meaning of resilience in the participants’ experiences

One of the main themes of the study was meaning of resilience with four sub-themes including; “the art of overcoming pain and suffering”, adapt to health problem of senescence”, “accepting life with the chronic disease”, and “patience and trust in God”.

The art of overcoming pain and suffering

The participants’ experiences showed that some of them perceived resilience as an art and a unique skill that help them face the pains and hardships of a long-term disease. One of them said:

being resilient is a skill, being me and keeping your spirit up is not easy, you cannot move, you cannot sleep well, and at the same time you have to deal with routine problems of life. I you know the trick, you will find it possible to cope with all these hardships. [an 80-year-old woman with asthma and blood pressure]

A 66-year-old woman (ache in the limbs due to spinal stenosis, blood pressure, and diabetes) noted

resilience is an art, and without it you would not have a chance to survive, I have lived with legs pain, diabetes, and blood pressure[…] but what helps me is my skill and art to cope with the problem. I cope the hardship by my trust in God. Right now, I can sleep well and my blood pressure and sugar are almost stable.

Adapt to health problem of senescence

As experienced by the majority of the participants, resilience meant adaptation to health problems of aging. They experienced coping with the diseases and avoiding what would intensify the symptoms as adaptation. An 80-year-old man with chronic cardiac pain, ankle joint pain, and colon cancer stated:

I have had legs pain for about 10 or 15 years not to mention high blood pressure…. I cope with it in the hope that someday a solution would be found for it. I try to avoid things that are bad for my health. I do not eat what is bad for me. I also try not to go outside too often.

Another participant said “I have had legs pain for one year. I would use lotion and oil and cover the area by a wrapper when the pain is high. This would usually help” [an 80-year-old man with joint pain].

Accepting life with the chronic disease

Some of the participants maintained that resilience means accepting the life with disease as an elderly. A 66-year-old woman with body pain due to spinal stenosis, high blood pressure, and diabetes stated that “diseases are inevitable as you grow old and the elderly accept their situation gradually.” Another participant noted about accepting diseases that “I have been afflicted with a variety of diseases since I have grown old. Now, having heart problems, fat, and blood pressure are normal part of life. It is the same for everyone” [a 72-year-old man with cardiovascular problems].

Patience and trust in God

Patience and trust in God was equal with resilience from the participants’ point of view. One said: “for me, resilience means patience and trust in God. With this, I have good and bad days. What makes me accept this is trust in God” [a 70-year-old woman under dialysis and with coronary artery problem and cataract]. Another participant noted that “resilience means having trust in God; means patience. He is the one who knows what is best for us and when is the best time to help” [a 79-year-old man with COPD].

Theme two: growth context as a prologue of resilience

Growth background and childhood experience were considered by the participants as predisposing factors for resilience in the later life.

Growth background

As noted by the participants, their childhood experiences of taking care of patients in their family or managing home when their parents were ill have made them prepared to deal with hardships of life. One said: “my mother had asthma. I was in charge of her medicine and the house as well. Her disease and the hardships of those days have made me strong enough to overcome the hardships now” [a 70-year-old woman with cardiac problems and cataract].

Some of the participants were grown up in stressful and turbulent family conditions and were less capable of dealing with their chronic disease. One said:

My mother used to tease me when I was a kid. She was not that kind of person who you would enjoy being around. She had had a hard childhood as well and treated her children the same way. There was always some reason for quarrel and violence, and this has made me a nervous person. That is why I am not very resilience. [a 73-year-old-woman with motor limitations due to diabetic foot]

Theme three: external factors contributing to resilience

The third main theme of the study was “external factors contributing to resilience”. The participants considered welfare and receiving emotional, financial, and other types of support as significant factors contributing to their resilience. In contrast, lack of others’ support and or losing them contributed to decreased resilience.

Welfare

The elderly stated that having good economic condition and financial independence was a sort of mental security and helped them being more resilient. One said:

One’s livelihood is critical. I am talking about financial condition. What if I had to do a surgery and I did not have the money. Death would be inevitable in that case. However, I was lucky being in good financial condition and treated myself before it was too late. [a 78-year-old man with stomach cancer]

Inability to pay for the medical services and economic dependence on children or others attenuate one’s ability to successfully deal with the problems caused by diseases. One participant noted:

as an elderly, you have to deal with variety of diseases. My social security insurance is a dime a dozen and I have no job. It would be much better if I had a job or a pension or something. With those, I would be more resilient. [a 65-year-old man with epilepsy]

Received support

Receiving support from relatives, medical team members, and public organizations and bodies were considered by the participants as factors in positive adaptation to chronic conditions. According to the participants’ experiences, the support they might receive from their family members especially spouse and children, neighbors, and friends would improve their resilience. One mentioned:

your wife and children are very important. They keep your spirit high. My family has done all they could to support me. Once I decided to go to a retirement center instead of being an extra burden, but my children rejected the idea seriously. [a 69-year-old man with respiration problems]

In the case of female participant, the spouse’s emotional support was more important to their resilience.

One of the participants said “the one thing that makes me sad is that why my husband never asked how did if fell” [a 65-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)]. While in the case of the male participants, the nursing role of the spouse was more important. One said “my wife really takes care of me, she is very sensitive about my sugar level. She is really concerned about my nutrition, medicine, and physical activity” [a 70-year-old man with diabetes and asthma]. Most of the participants noted the importance of the supports they would receive from the medical team members on their resilience. One highlighted:

I have to be hospitalized here, then nobody cares about me. The nurse forgets to give the medicine on time,…. I am supposed to have special food for cardiac patients, but they give me usual food with high fat. If you complain, that answer is “take it or leave it”. So, how do I suppose to cope with this. [a 65-year-old woman with cardiac failure and arthrosis]

Deprivation and shortages

One of the main reasons for a decrease in resilience was the absence of family members and loved ones, loss of physical capabilities, and deprivation from human dignity. The absence of loved ones such as spouse in particular and being deserted by children were the factors that negatively influenced resilience. One mentioned “my husband was a great support. It was OK while he was alive. After him, I have suffered a lot. It seems like I have lost everything. I cannot stand anything” [a 79-year-old woman with chronic headache]. Loss of physical capabilities was another factor that negatively influenced resilience of the participants. One said:

This disease is a nightmare… I cannot see well. I cannot do many things. Once I was very active and now I cannot even go into the neighborhood. It has been years since my last pilgrimage. I am imprisoned in my house. These make the life unbearable. [a 77-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis and cardiac failure]

Negligence of human dignity and disrespectful behavior toward an elderly were also the factors that could reduce resilience. One participant mentioned: “I cannot handle my personal affairs. Sometimes my children help me. I feel their reluctance, however. You can see it when you ask them twice. I think it is quite alright to be less resilient in this condition” [a 70-year-old woman with coronary artery disease and cataract].

Attitude toward an elderly with health problem

The participants mentioned experiences that indicated society’s attitude toward elderly with health problems, which was effective on resilience of the participants. According to the participants’ experiences, lack of social acceptance reduces their interaction with the outside world and their resilience as well. “I lost my job when the convulsions began. I cannot go anywhere. We barely see the relatives and friends. They do not trust me doing anything in the mosque. They tell me you are sick and you cannot” [a 65-year-old man with asthma].

Theme four: personal factors to overcome illness

The final main theme of the study was “personal factors to overcome illness”. The participants considered personal factors as significant factor behind their resilience. They noted that enthusiasm for following up the treatment program, aversion to physical dependence, having hope, purpose in life, and being content with one’s blessing and belongings enhanced their resilience.

Enthusiasm for following up the treatment program

The participants noted that being enthusiastic and following the physician’s instruction accurately were the factors that helped the patients being more resilient. One said: “I have suffered heart problem for 20 years and I have not forgotten my medication even once. I am serious in following the regimen and taking the medicines on time; no matter if I am on trip or a guest in someone’s house” [a 65-year-old man with mitral valve implant].

I am very careful about my disease. I exactly follow the prescriptions and refill the medicine box 2 or 3 days before it is empty. I would inform my physician about any changes in my health condition. I am really sensitive about my health condition and follow the doctor’s order accurately. [a 67-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease]

Aversion to physical dependence

Aversion to physical dependence was an incentive for the elderly to preserve their health and avoid recurrence of the disease. One said: “when my disease recurs, dyspnea does not allow me doing anything. It is really hard. I am very nervous when I have to depend on someone else” [a 79-year-old man with COPD]. I cannot stand being depended on somebody. Therefore, I am very cautious about my disease… to avoid more serious problems and dependence on others [a 65-year-old woman with diabetes].

Hope for improvement

Majority of the participants mentioned hope for improving conditions, medical advances, and God’s help as another factor related to resilience. One said “I have this disease [cancer]. I have not gave up. I do not mean that I am immortal. Who knows, maybe they find better cures for it while I am around. You should not give up” [an 80-year-old man with blood cancer].

Another patient mentioned hope for God’s help as a factor that helped him cope with disease: “I have great hope for God’s help. He can cure me if He wants” [a 65-year-old woman with SLE].

Motivation and purpose

The participants mentioned that motivation and purpose in life result in their resilience. Love for family, feeling responsible toward the family, and preserving one’s dignity and respect were some of the motivations for resilience. One of the participants said:

We are expected to preserve our health for the others’ sake…because, after God, because as the man of the family, I am the only hope they have. I have taken pressure pills for 20 years and lived as a diabetic for 30 years. I follow the doctor’s prescription exactly…I know the future is not so bright for me and I will lose. [a 66-year-old man with cardiac problem and diabetes]

Another participant mentioned his dignity and respect as the motivation of his resilience and said: “It is very important for me being respected and having dignity. The elderly keeps his/her dignity by keeping his/her capabilities to do personal jobs. If you lose your abilities, you will lose your dignity as well” [a 69-year-old man with chronic pulmonary disease].

Being content with one’s blessing and belongings

Another factor that improved resilience of the participant was recognizing one’s blessing and belongings. Some mentioned that they find hope when they think about their blessings. “I have a good wife. The children are good. I still have the power to walk. All these give me hope” [a 67-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease].

Other participants mentioned that “by now it is one year that I have been diagnosed with blood cancer; if you look on the bright side, I have lived 79 years with good health and no need for medical attention” [an 80-year-old man with blood cancer].

Discussion

The concept of resilience was examined from a phenomenological viewpoint based on experiences of the elderly with chronic diseases. The participants found resilience as an art, and relying on their trust in God they managed to accept their lives with their chronic disease. Using this art, the participants were able to overcome the pain and hardship of their chronic disease. The prologue of resilience was their growth context, and its structure was composed of a set of external and personal factors. In various studies, resilience has different meanings. The study of Hildon et al, resilience equated with maintaining a good quality of life,18 while in the Demakakos et al’s19 study the meaning of resilience was lack of depression or non-worsening of depression. In addition, in another study, its meaning was “perceived health”. According to the results, it seems that the meaning of resilience is under effective religious and cultural context of each society.20

Herrman et al21 defined resilience as positive adaptation or ability to preserve health or regaining mental health despite the experience of hardships and challenges. Adaptation is one of the skills used by the elderly in the face of stressors. The elderly try to adapt by modifying their perception about their situation, accepting their disease, and hoping for improvement.22 Our findings highlighted resilience as an art and skill, which enables the patients to adapt to their chronic disease; however, what was more important in the meaning of resilience for most of the participants was trust in God and patience. Experimental studies have proved the importance of trust in God as a coping strategy to attenuate anxiety and depression and boost hopes.23 Several subjects in Darrell’s study noted that their trust in God helps them remain calm in the face of their disease.24 Sharpley et al25 found that the main factors in resilience were “trust in oneself to deal with changes”, “trust in a superior power”, and “capability to take hard measures”.

In the current study, the prologue of resilience was the growth background. In a study conducted in Hong Kong, early living conditions and experiences such as family socialization, religious faith during the elders’ childhood, working life, and other experiences have been associated with resilience in older age.26 Past success is the strength that fosters resilience for the later life.27 Some experiences can be traumatic for the elders, whereas the others serve to buffer the trauma. Eventually, they function to contribute to the resiliency of the elders.26

As our findings showed, personal factors, such as following the treatment program enthusiastically, resenting dependence on others, feeling love for family, trying to keep one’s dignity, hope for medical advances and God’s blessing, and being content with one’s belongings and blessing, were the main sources that the participants used to overcome the problems caused by their diseases. According to Zautra et al,28 personal specifications and conditions would determine the resilience processes. Amtmann et al29 highlighted that resilience is a dynamic process consisted of cognitive, behavioral, and inter-personal skills and many of them are acquirable over time. For instance, a study on diabetes type II patients showed that resilience is a notable skill in dealing with unpleasant and hard situations. The resilient person enjoys high ability to control; this helps the patient with chronic disease to feel being in control of their condition. These patients find themselves capable of playing an active role in using coping strategy to fight their bad situation.30 Experience of the elderly who has received long-term health care indicates that one of the main sources of resilience are personal factors such as believing in one’s competence, ability to analyze and perceive the current situation and capability to establish relationships.11

One of the resilience sources was external factors contributing to resilience. Sippel et al noted that people have high potential to adapt to hardships; however, adaptation process entails interaction and function of many internal and external systems.31 For example, social support is one of the factors. DiMatteo32 showed that the patients with high social support had more tendency to observe their treatment plan and more desire to use health and medical services. In addition, family support was mentioned as a key factor in resilience of the elderly. Social support improves healthy behaviors,33 and it is more effective when it is from the person who is expected to show such support.34 Shankar et al35 showed that social seclusion was negatively affective on health in the elderly.

In the current study, organizations, medical team, and acquaintances constituted a social support network that provided emotional, instrumental, and financial support to control the stress of chronic disease. Importance of social support on resilience of the elderly was a function of type of support and needs of the patient. For instance, women expected emotional support from the spouse and children, while men expected physical health care from their family members.

It appears that economic condition has different effects on resilience depending on social context. Financial independence is not a critical factor in the societies that the elderly receive adequate and free/inexpensive medical and health services.

A number of studies have been found linking resilience to socioeconomic status. Beutel et al36 found that higher household income is associated with greater resilience, while Wells37 found that a negative relationship between income level and resilience. There has been no association between resilience and an older person lives in a rural or urban environment.38 Researchers have shown men to be more resilient in older age,19,39 while at least one study found women to be more resilient40; in addition, studies have found that resilience does not decline with age, and older people have similar or higher resilience scores than younger.19,41,42

Limitations

The practical application of the results of the current study for other people and in other locations may be limited, because the results of qualitative studies are not easily generalizable.

Implications of the study for policy and practice

The elderly population is growing worldwide. It is important that health care provider be aware of the potential role of resilience in relation to successful aging. Understanding the meaning and structures of resilience in older people may help them to strengthen their self-efficacy for disease management, overcome the problems in relation to health, and improve the quality of life. Therefore, the results of this study need to be valued in the health system. Health care providers can use these experiences to develop holistic caring plans.

Conclusion

The findings of this study clarified the meaning and structures of resilience among hospitalized older adults with chronic conditions. Accordingly, the current study contributes a level of richness and depth to the concept of resilience. There is no standard intervention to improve the resilience of patients with chronic diseases. Further insight into the meaning and structures of resilience in Iranian older adults can result in international comparisons and in the potential development of interventions based on positive strategies of adaptation to improve resilience for this group worldwide.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a PhD dissertation approved by Tehran Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Science. The authors would like to thank all the participants and those who helped them in conducting this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Mirzaei M, Shams-Ghahfarkhi M. Demographic characteristics of the elderly population in Iran according to the census 1976-2006. Iran J Ageing. 2007;2(5):326–331. | ||

UN DESA. World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision. New York, NY: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat; 2013. | ||

Trivedi RB, Bosworth HB, Jackson GL. Resilience in chronic illness. In: Resnick B, Gwyther LP, Roberto K, editors. Resilience in Aging. New York: Springer; 2011:181–197. | ||

Boyd CM, McNabney MK, Brandt N, et al. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the care of older adults with multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(10):E1–E25. | ||

Southwick SM, Litz BT, Charney D, Friedman MJ. Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. | ||

Roger VL, Go AS, Loyd-Jones D, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics. A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. | ||

Jeste DV, Depp CA, Vahia IV. Successful cognitive and emotional aging. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(2):78–84. | ||

Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol. 2004;59(1):20–28. | ||

Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1–7. | ||

Aléx L. Resilience among very old men and women. J Res Nurs. 2010;15(5):419–431. | ||

Janssen BM, Van Regenmortel T, Abma TA. Identifying sources of strength: resilience from the perspective of older people receiving long-term community care. Eur J Ageing. 2011;8(3):145–156. | ||

Pentz M. Resilience among older adults with cancer and the importance of social support and spirituality-faith: I don’t have time to die. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2005;44(3–4):3–22. | ||

Yang F, Bao JM, Huang XH, Guo Q, Smith G. Measurement of resilience in Chinese older people. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62(1):130–139. | ||

Friedman EM, Ryff CD. Living well with medical comorbidities: a biopsychosocial perspective. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67(5):535–544. | ||

Van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Abany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1990. | ||

Colaizzi P. Psychological research as the phenomenologist’s view it. In: Vale R, King M, editors. Existential–Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1978:48–71. | ||

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. | ||

Hildon Z, Smith G, Netuveli G, Blane D. Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30(5):726–740. | ||

Demakakos P, Netuveli G, Cable N, Blane D. Resilience in older age: a depression-related approach. In: Banks J, Breeze E, Lessof C, Nazroo J, editors. Living in the 21st Century: Older People in England. London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies; 2006:186–221. | ||

Gallacher J, Mitchell C, Heslop L, Christopher G. Resilience to health related adversity in older people. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 2012;13(3):197–204. | ||

Herrman H, Stewart DE, Diaz-Granados N, Berger EL, Jackson B, Yuen T. What is resilience? Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(5):258–265. | ||

Kuria W. Coping with Age Related Changes in the Elderly [thesis]. Glenside: Arcadia University of Applied Sciences; 2012 | ||

Ghobari BB, Shojaei M. Relationship between reliance on god and self-esteem. Int J Psychol Psychoanal. 2004;39(5–6):381–381. | ||

Darrell L. Faith that god cares: the experience of spirituality with African American hemodialysis patients. Soc Work Christianity. 2016;43(2):189–212. | ||

Sharpley C, Bitsika V, Wootten A, Christie D. Does resilience “buffer” against depression in prostate cancer patients? A multi-site replication study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;23(4):545–552. | ||

Cheung CK, Kam PK. Resiliency in older Hong Kong Chinese: using the grounded theory approach to reveal social and spiritual conditions. J Aging Stud. 2012;26(3):355–367. | ||

Chapin R, Nelson-Becker H, MacMillan K. Strengths based and solutions-focused approaches to practice. In: Berkman B, D’Ambruoso S, editors. Handbook of Social Work in Health and Aging. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006:339–354. | ||

Zautra AJ, Hall JS, Murray KE. Resilience: a new definition of health for people and communities. In: Reich JR, Zautra AJ, Hall JS, editors. Handbook of Adult Resilience. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010:3–30. | ||

Amtmann D, Verrall AM, Terrill AL, et al. Resilience in the context of chronic disease and disability. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:44–44. | ||

Mazlum Befruee N, Afkhami Ardakani M, Shams Esfandabadi H, Jalali M. Investigating the simple and multiple resilience and hardiness with problem-oriented and emotional-oriented coping styles in diabetes type 2 in Yazd city. J Zabol Nurs Midwifery. 2012;1(2):39–49. Persian. | ||

Sippel LM, Pietrzak RH, Charney DS, Mayes LC, Southwick SM. How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecol Soc. 2015;20(4):136–145. | ||

DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207. | ||

Cohen S, Lemay EP. Why would social networks be linked to affect and health practices? Health Psychol. 2007;26(4):410. | ||

Selcuk E, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness moderates the association between received emotional support and all-cause mortality. Health Psychol. 2013;32(2):231. | ||

Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):377. | ||

Beutel ME, Glaesmer H, Wiltink J, Marian H, Brähler E. Life satisfaction, anxiety, depression and resilience across the life span of men. Aging Male. 2010;13(1):32–39. | ||

Wells M. Resilience in rural community-dwelling adults. J Rural Health. 2009;25(4):416–414. | ||

Wells M. Resilience in older adults living in rural, suburban, and urban areas. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2012;10(2):45–54. | ||

Hardy SE, Concato J, Gill TM. Resilience of community-dwelling older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):257–262. | ||

Netuveli G, Wiggins RD, Montgomery SM, Hildon Z, Blane D. Mental health and resilience at older ages: bouncing back after adversity in the British Household Panel Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(11):987–991. | ||

Gooding PA, Hurst A, Johnson J, Tarrier N. Psychological resilience in young and older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(3):262–270. | ||

Nygren B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(4):354–362. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.