Back to Journals » Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine » Volume 5

Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites in children from Verón, a rural city of the Dominican Republic

Authors Childers K, Palmieri JR , Sampson M, Brunet D

Received 27 March 2014

Accepted for publication 16 May 2014

Published 10 July 2014 Volume 2014:5 Pages 45—53

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RRTM.S64948

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Kristin A Geers Childers, James R Palmieri, Mindy Sampson, Danielle Brunet

Department of Microbiology, Infectious and Emerging Diseases, Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Abstract: Gastrointestinal infections impose a great and often silent burden of morbidity and mortality on poor populations in developing countries. The Dominican Republic (DR) is a nation on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea. Verón is located in La Alta Grácia province in the southeastern corner of the DR. Dominican and Haitian migrant workers come to Verón to work in Punta Cana, a tourist resort area. Few definitive or comprehensive studies of the prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitic infections have been published in the DR. Historically, most of the definitive studies of water-borne or soil-transmitted parasites in the DR were published more than 30 years ago. Presently, there is a high prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitic infections throughout the poorest areas of the DR and Haiti. In this study we report the prevalence of gastrointestinal protozoan and helminth parasites from children recruited from the Clínica Rural de Verón during 2008 through 2011. Each participant was asked to provide a fecal sample which was promptly examined microscopically for protozoan and helminth parasites using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) fecal flotation technique to concentrate and isolate helminth ova and protozoan cysts. Of the 128 fecal samples examined, 127 were positive for one or more parasites. The age of the infected children ranged from 2–15 years; 61 were males and 66 were females. The only uninfected child was a 9 year old female. Percent infection rates were 43.8% for Ascaris lumbricoides, 8.5% for Enterobius vermicularis, 21.1% for Entamoeba histolytica, and 22.7% for Giardia duodenalis. Of the children examined, 7.8% had double infections. Any plan of action to reduce gastrointestinal parasites in children will require a determined effort between international, national, and local health authorities combined with improved education of schools, child care providers, food handlers, and agricultural workers. A special effort must be made to reach out to both documented and undocumented immigrants working or living in the area and to pre-school aged children or those who are not part of the public education system. Lastly, it is important to address the microbial water quality and food preparation, especially during the weaning transition to solid foods and throughout childhood.

Keywords: Ascaris lumbricoides, Entamoeba histolytica, Enterobius vermicularis, gastrointestinal, Giardia duodenalis, parasite

Introduction

Gastrointestinal infections impose a great and often silent burden of morbidity and mortality on poor populations in developing countries.1 Soil-transmitted helminths (STH) are among the most prevalent pathogenic organisms on the planet. It is estimated that almost one sixth of the global population is infected with STH; the highest rates among school-aged children who are frequently infected with two or more species simultaneously.1,2 In addition, in the developing world, microbial contamination of drinking water results in parasitic disease transmission; water and food-borne parasitic protozoa include Entamoeba histolytica (E. histolytica) and Giardia duodenalis (G. duodenalis).2 Eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides (A. lumbricoides) are found in soil and drinking water contaminated by human feces, and in foods contaminated with embryonated eggs.2 There are approximately 60,000 deaths per year, mainly in children, in the developing world due to STH infection, a large percentage of which is caused by A. lumbricoides.2–4

The Dominican Republic (DR) is a nation on the island of Hispaniola, part of the Greater Antilles Archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. The western third of the island is occupied by the nation of Haiti, making Hispaniola one of two Caribbean islands that is shared by two countries. The DR is the second largest Caribbean nation with 48,445 square kilometers with an estimated 10 million people, one million of whom live in the capital city of Santo Domingo. The official language is Spanish.5–8 The Verón municipality is located in La Alta Grácia province in the southeastern corner of the DR. The population of Verón is estimated at 8,000 and is made up of mostly migrant families with the average length of residence being 6 years.9 Many immigrants come to Verón to work in highway development in construction, and in support of the tourist industry centered in resorts scattered along the coastline of Punta Cana. Punta Cana, part of the Punta Cana-Bávaro-Verón-Macao municipal district, is known for its beaches which face both the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Punta Cana has been a popular tourist destination since the 1970s. Migrants come to Punta Cana from many provinces of the DR including Santo Domingo (14%), Sebo (12%), La Alta Grácia (9%), Barahona (8%), and La Romana (8%). There is a large number of unregistered Haitian immigrants who make up an unknown portion of the migrant population of this region.10 The majority of inhabitants in this area are uninsured and without access to health care. Most rural homes consist of two to three rooms, housing six or more people, many of whom are infected with a variety of parasitic diseases.9

For reasons unknown to the authors, few definitive or comprehensive studies of the prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitic infections in the DR have been published. There has been a scattering of published reports involving groups of tourists who have returned to their country of origin (eg, Spain, USA) who reported parasitic infections following a stay in the DR.11,12 One of the few comprehensive reports was published in 2011 by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) on the prevalence and intensity of STH in Latin American and Caribbean countries.13 This report was constructed from data collected between 2000 and 2010; PAHO reported an absence of any major published study on STH for the DR. This is in great contrast to Haiti for which PAHO reported several definitive published studies on STH, even though Haiti and the DR share the same island.13 In October 2009, PAHO approved resolution CD49.R19 stating the commitment of PAHO’s member states to eliminate or reduce neglected diseases, including STH, to levels that would no longer be considered a public health problem by the year 2015.1,14,15 This published study reported PLoS neglected tropical diseases for STH, which included a total of 236 publications and research articles from 1995 to 2009 in primary scientific journals. These were analyzed for Latin American and Caribbean nations; none of which contained publications reporting data from the DR.1 PAHO concluded that there was an overall deficiency of definitive reports published for the DR.1

Historically, most of the definitive studies of surveys of water-borne or soil-transmitted parasites in the DR were published more than 30–50 years ago. For example, a survey published by Mackie et al in 195116 on the prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitic infections, was conducted among labor populations of two sugarcane plantations in the DR during the summer of 1949 and the winter of 1950; both plantations were several kilometers inland from the coast. Fecal specimens were examined promptly for helminth eggs and protozoan cysts following delivery of samples to their laboratory. Mackie reported E. histolytica from 390 individuals (32.4%), G. duodenalis from 56 (4.9%), A. lumbricoides from 229 individuals (20.1%) and Enterobius vermicularis (E. vermicularis) from only two of the 1,039 adults sampled.16 In a more qualitative study by Collins and Edwards (1981), they reported sampling feces for the presence of parasites in a population of 453 individuals from rural areas of the DR and found A. lumbricoides, G. duodenalis, and E. histolytica.17 They concluded that parasitism was considered a common condition in rural populations in the DR and that A. lumbricoides was one of the more frequently encountered helminths. E. vermicularis was the most common helminth reported in children less than 10 years old and in older adult patients. Collins and Edwards also reported a low prevalence of protozoan infections.17

Presently, there is a high prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections throughout the poorest areas of the DR and Haiti.5,18,19 Inhabitants of the DR are infected with a number of gastrointestinal parasites including: nematodes (A. lumbricoides, E. vermicularis, Necator americanus, Trichuris trichiura); cestodes (Taenia saginata, Taenia solium); and protozoa (E. histolytica, G. duodenalis). These parasites cause a wide range of gastrointestinal symptoms from mild to severe and are often associated with diarrhea. In the DR, acute diarrhea is one of the top five reasons given for medical consultation. Poor water sanitation is a main cause of endemic disease in the DR. The estimated burden of ascariasis in the DR surpasses 456,000 cases per year.5 Children are particularly affected by A. lumbricoides.20 At the global level it is estimated that all intestinal parasitic infections affect more than one third of the world’s population with the highest rates of infection in school-age children.13 Growth stunting usually occurs between 6 months and 2 years of age.13,18 PAHO estimated that less than 46% of individuals living in rural areas of the DR have access to clean drinking water and only 16% of the entire population has sanitary sewage disposal services. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports 1.8 million deaths annually from diarrheal diseases, with 88% attributed to inadequate sanitation, poor hygiene, and unsafe water supplies; 95% of deaths were in children less than 5 years old.13,21,22

Beginning in 2006 and through to the present, the Edward Via Virginia College of Osteopathic Medicine (VCOM), established a collaboration with the DR Ministry of Public Health, or la Sociedad Española de Salud Pública y Administacion Sanitaria, and the Punta Cana Foundation, to establish an outpatient medical care clinic and laboratory in Verón, La Clínica Rural de Verón, to develop a program to provide care for the medically underserved in the surrounding areas. This rural clinic has become a functional medical facility in the community, providing health care services. On an average day 60 to 90 patients are evaluated and treated. This study reports the gastrointestinal parasites recovered from children brought to the clinic for a variety of reasons. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of human gastrointestinal parasites in children aged 2–15 years, who presented to the Clínica Rural de Verón.

Materials and methods

In this study we report the data collected during 2008 through 2011. Participants from Verón and the rural surrounding areas were recruited from the Clínica Rural de Verón. Informed consent was obtained from all participants including the parents or legal guardians of minors. In addition, when appropriate, all minors signed an assent form. This project was reviewed by the VCOM Institutional Review Board prior to the collection of any data. Each participant was asked to provide a fecal sample which was promptly examined microscopically for protozoan and helminth parasites. In addition, a fecal flotation technique was used to concentrate and isolate helminths, helminth ova, and protozoan cysts according to the protocol established by the CDC and the percentage infection rates determined.23

Results

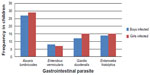

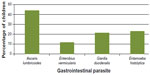

Of the 128 fecal samples examined for gastrointestinal parasites, 127 were positive for one or more parasite species (Figure 1). The age of the children examined ranged from 2–15 years; 61 were males and 66 were females (Figure 2). The only uninfected child was a 9 year old female. Percentage infection rates were 43.8% for A. lumbricoides (Figure 3), 27 males and 29 females; 8.5% for E. vermicularis (Figure 4), eight males and seven females; 21.1% for E. histolytica (Figure 5), 12 males and 15 females; and 22.7% for G. duodenalis (Figure 6), 14 males and 15 females. Of the children examined, 7.8% had double infections, four females and six males. Of the four females, three had both A. lumbricoides and E. vermicularis and one had A. lumbricoides and E. histolytica; and of the six males, five had A. lumbricoides and E. vermicularis and one had E. vermicularis and G. duodenalis. These data are summarized in Figures 1 and 2.

| Figure 1 Frequency of gastrointestinal parasites identified in children aged 2–12 years from Verón, Dominican Republic. |

| Figure 2 Percentage of children aged 2–12 years from Verón, Dominican Republic infected with each gastrointestinal parasite. |

| Figure 3 Trophozoite and cyst stages of Giardia duodenalis in a stained fecal smear. |

| Figure 4 Stained cyst stage of Entamoeba histolytica from a fecal sample. |

| Figure 5 Egg of Enterobius vermicularis recovered from a fecal sample. |

| Figure 6 Egg of Ascaris lumbricoides recovered from a fecal sample. |

| Figure 7 Pregnant mother from Verón with her child who is waiting to be vaccinated against polio. |

Discussion

Poverty and parasitic infections in the DR

It is interesting to note that 127 of the 128 children examined in this study were positive for one or more gastrointestinal parasite. Children were usually brought to the Clínica Rural de Verón with a health problem, most commonly upper respiratory, but not necessarily for parasitic related symptoms (Figure 7). The high prevalence of infection reported in this study demonstrates the potential burden of parasitic infections in children in this area of the DR. Hookworm, Trichuris trichiura and Hymenolepis diminuta were not reported in our study, although these parasites have been reported in children in the DR by other investigators.5,12,16,17,20 A possible explanation is that our study sample consisted of both healthy and sick children, and not always with gastrointestinal complaints. Furthermore, this study was not conducted on children in their rural home environment.

Historically, there is a degree of cyclic closeness between poverty and parasitic diseases on the island of Hispaniola, beginning when slaves were brought to the island from Africa between 1492 and 1870.5,24 Presently, the health of young children and pregnant women in the DR is impacted directly by acute and chronic parasitic infections.25 There is a distinct economic dichotomy existing in the DR made up of tourists who vacation at the resorts of Punta Cana and those who live in the hidden underbelly of poverty in the surrounding areas. It is here where parasitic protozoa and helminths disproportionately affect the most disadvantaged, often trapping vulnerable individuals in a cycle of poverty and disease.25–27 The health consequences of parasitic infections in this area also impact tourists who visit and subsequently become infected.11 But the more devastating impact in the DR is found where parasitic diseases slow the mental and physical growth of children, complicate pregnancies and birth outcomes, and have long term effects on educational achievement and economic activity.25 Parts of Verón fit the classic definition of a shantytown, an area located at the periphery of the city where low-cost dwellings, contaminated water sources, and open pit public toilets are common.28 Often families in these areas do not have enough food for the entire family and every family member must work. Early marriages, large families, and single mothers contribute to the cycle of poverty which often continues generation after generation. Without fundamental services such as clean water and proper sanitation, communicable diseases continue to have a significant presence in the DR, resulting in morbidity and mortality among children.29,30 In the 2011 PAHO report, it was estimated that the death of 30% of infants less than 1 year of age (38% in ages 1–4 and 26% in ages 5–14) can be attributed to communicable diseases.13 Communicable diseases presenting as diarrhea and respiratory symptoms account for 61% of all mortality in children in the DR.13,29

Parasitic infections in the indigenous and the migrant populations

Parasitic infections in the DR are widespread resulting from factors that include immigration, cultural beliefs, lack of education, and contaminated food and water sources. Verón’s population consists of many Haitian immigrants. While the exact number of Haitian immigrants in Verón is unknown, the literacy rate for Haiti was only 48.7% while the literacy rate for the DR in 2011 was 90.1% according to Index Mundi.7,8 Haitians in Verón lowers the total literacy rate for the area; furthermore, many Haitian immigrants speak only Creole. Therefore, the development of any educational program for parasite prevention would be considerably hindered by illiteracy and language barriers.31 The lack of education in some groups in Verón is another factor contributing to the lack of control of parasitic infections. Primary education in the DR is provided free for all children from the ages 7 to 14, and although attendance is compulsory, attendance is rarely enforced, especially in the rural areas.7,8,32 Many immigrants and local inhabitants work as child care providers, food handlers, and agricultural workers, which positions them in a role that may contribute to the transmission of parasitic diseases.33,34

The lack of access to clean water contributes to propagation of disease. In a 2014 study that examined relationships between microbial drinking water quality and the drinking water sources in the Porto Plato region of the DR, it was found that 47% of “improved drinking water sources” were of high to very high risk-water-quality and therefore unsafe to drink.21 The study concluded that just because water quality has been deemed “improved” it may still be at high risk for microbial contamination.21 Over the past 20 years the percentage of the population in the DR with access to improved water sources has decreased slightly from 89% in 1990 to 82% in 2011.21,35 However, this value would likely be greatly reduced due to the microbial contamination of so-called “improved water sources”.21 According to the WHO/United Nations Children Fund Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (2012), an “improved drinking water source” is defined as any piped water inside the dwelling or outside in a family plot or yard, any public taps or stand pipes, tube wells or boreholes, protected dug wells, protected springs, or rain-water collection areas. This definition, although identifying improved water sources, fails to account for microbial water quality and therefore over-estimates the population with “access to safe drinking water”.36,37 In a study by McLennan (2000), 582 caregivers of children who were less than 5 years of age were systematically sampled from four neighborhoods in a poor peri-urban community of Santo Domingo. McLennan reported that 55% of caregivers did not boil drinking water for children, 38% did not always wash the children’s hands prior to meals, 87% of children did not always wear shoes outside their house, and 54% were breastfed for less than 1 year;38,39 all these being important factors contributing to parasite transmission.

Contaminated weaning foods account for a substantial portion of parasite-induced diarrheal diseases among infants and young children.33 Nutritional deficiency disease such as protein-energy (calorie) malnutrition, iron deficiency anemia, and vitamin A deficiency has been reported in connection with food-borne parasitic infections including giardiasis and ascariasis.33 The sources of food contamination are numerous and without appropriate food safety measures and hygienic quality control of infant foods including drinking water, parasitic infections will remain high in both infants and children. Health education and food safety procedures for food handlers and caregivers who are responsible for infants and children is imperative if parasitic infections in this age group are rather than this.40,41

During May 2013, a PAHO/WHO regional meeting was held in Bogota, Colombia in order to promote an integrated action to control STH and to supply guidance for the implementation of integrated deworming actions among the 18 country members in the region of the Americas.1,20 This report is significant because it gives current information about helminth infections in the DR, a nation which is lacking large scale published peer reviewed reports on the prevalence of gastrointestinal parasitism. PAHO/WHO reported that gastrointestinal parasitic diseases are among the 15 leading causes of morbidity in children in the DR; 55.3% involved STH. Approximately 31% of children aged 1–18 years suffer from anemia, partially because of parasitic infection. Between 50%–60% of children in the DR are infected with at least one type of parasite; gastrointestinal parasitism occurs more frequently in children 6–10 years.20,42 More than half of these children are infected with more than one species of parasite.9 Young children are particularly vulnerable during the time when physical and mental developmental growth takes place. This growth is affected by malabsorption, blood and protein loss, diarrhea, chronic dyspeptic syndrome, appetite suppression, and nutrient diversion, all potentially a result of chronic or recurrent parasitic infection.1,20,42 This report (PAHO/WHO) recommended monitoring and evaluating the impact of deworming programs in the DR through the utilization of prevalence and intensity surveys. They also recommended that deworming programs be integrated in private and public elementary schools as well as with non-enrolled or absentee school-aged children who make up approximately 8% of school-aged children in the DR.1,20 In addition the PAHO/WHO committee recommended that the DR scale-up deworming activities to include pre-school-aged children and to also implement bi-annual deworming campaigns to cover other at-risk groups such as pregnant women and agricultural workers.42 Intervention programs that combine prevention and control of parasite infections and promote healthier diets will be the most effective in improving growth and development of infants and school aged children in the DR according to PAHO/WHO.42

Parasitic infections in travelers, the immunocompromised, and those who emigrated from the DR

Travelers’ diarrhea (TD) affects 8%–50% of travelers; incidence varies according to travelers’ country of origin and destination.43 The DR is considered a high-risk destination. TD is often acquired through fecal-contaminated food and water. Consuming food from street vendors is associated with enhanced risk.43 Young children are at particular risk because they have a propensity to touch multiple objects and to put them in their mouths. Children are less selective in sources and types of food ingested and their gastrointestinal immunity is not as robust as adults’.43,44 Although viral pathogens such as the Norovirus and Rotavirus may be responsible for up to 10% of cases of TD, parasitic infections account for a small minority of cases of TD lasting only a few days.45 Protozoan parasites such as G. duodenalis and E. histolytica, are less common causes of TD but protozoan parasites increase in importance when diarrhea lasts for longer than 2 weeks.43,45,46 Travelers with diarrhea lasting more than 10–14 days should be evaluated for any number of intestinal parasites including E. histolytica, and G. duodenalis.4–47 There are sporadic reports of tourists who became infected with gastrointestinal parasites following visits to the DR. For example, during 2002, while vacationing at a hotel in Punta Cana, many Spanish tourists complained of illness upon returning home.11 The Spanish National Centre of Epidemiology initially identified 76 cases of gastroenteritis in these tourists. They stayed in the same hotel in Punta Cana; their holiday package included all meals and beverages served by the hotel. All of the Spanish tourists consumed tap water and ice solely from the hotel’s private water well. Symptoms included abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, chills, nausea, headache, bloody diarrhea, and constipation; several required hospitalization. Cysts of E. histolytica were recovered from several of the patients while in the DR and three of 51 stool samples were positive for Giardia antigen (ELISA) when tested in Spain.11 In persons living in high risk areas of the Caribbean, especially in the DR and Haiti for 1–12 months,47 a chronic malabsorption syndrome, Tropical sprue (TS) is often seen. TS, usually a diagnosis of exclusion, is characterized by foul smelling stool, cramping, bloating, mild to moderate abdominal pain, weight loss, anorexia, and fever; G. duodenalis and E. histolytica are characteristically found in those diagnosed with TS.34

The number of immunocompromised international travelers has been increasing since the onset of the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s and since the increase in usage of immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory drugs for a variety of illnesses.48,49 Prevention of tropical and parasitic infections in immunocompromised travelers constitutes a special risk group who often do not seek nor receive adequate travel advice.48 The immunocompromised traveler is at greater risk of acquiring multiple parasitic infections which may result in persistent diarrhea often caused by G. duodenalis and E. histolytica.48,50

Prolonged diarrhea lasting more than 14 days occurs in 1%–3% of travelers; protozoan infections often include G. duodenalis and E. histolytica which account for the majority of cases.50 G. duodenalis is the most common parasitic agent of persistent diarrhea and increasingly found in areas of low sanitation. G. duodenalis can be found in 5%–7% of stools in the general population of the US, and in 15%–30% of stools in endemic areas. G. duodenalis is the most likely pathogen to infect travelers.50,51 E. histolytica has also been implicated in both diarrheal and invasive diseases affecting the liver and the other organs. The majority of patients who travel to endemic areas are asymptomatic or have intermittent diarrhea with mild abdominal tenderness.50,51

There have been reports of children and adults who have immigrated to New York City from the DR bringing with them parasitic infections. A study, conducted at a major New York City medical center, reported parasitic infections in immigrants from the DR.52 Of the 41,958 stool samples examined, 7,803 were positive for parasitic infections. Parasitic protozoa accounted for 53.8% of all isolates seen from 1971 through 1984. These included G. duodenalis (75.4%) and E. histolytica (20.1%). In addition, 38% were positive for intestinal helminths; stool samples included eggs of A. lumbricoides (9.5%) and E. vermicularis (10.9%).12 Neeley et al (1998) reported parasitic infections in immigrant children newly enrolled in the New York City school system. Of these immigrants, 119 (38%, ages 4–18, mean 10 years) were from the DR.52 All the children in this study were asymptomatic yet 74% were infected with one or more of the following: E. histolytica (24%), G. duodenalis (21%), and A. lumbricoides (6%).52

Solutions for the prevention and treatment of parasitic infections in children in the DR

One of the more effective methods for decreasing the rate of gastrointestinal parasitism in children in the DR would be through an integrated program for the elimination of helminth and protozoan parasites designed at the national level and implemented at the local level. Developing a national policy and plan of action requires the creation of updated strategies to combat parasitic infections in children. Examples of policies include widespread treatment programs and a better prevalence and surveillance mapping system.25 Greater attention must be directed toward economic and cultural barriers experienced by caregivers of children.38 PAHO, in their 2011 report, estimated the cost to control parasitic worms in the DR over 5 years would average US$0.38 per individual per year for a total of 3,585,858 treatments delivered for an estimated cost of US$623,155.25 Compliance with medical advice is an important component of medical care but it cannot take place unless patients understand and retain physician’s advice. Recall of the physician’s advice usually does not diminish with the passage of time once information is internalized by the patient.53 Without this understanding, any new national policy or treatment program will not be fully realized due to lack of patient compliance.

The use of new tools to predict the prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites requires that health workers are trained on using the tools correctly. These workers must be familiar with the software and the equipment so that they may effectively access national, international, and private research databases. This allows them to make accurate estimates of infections and to direct appropriate methods of treatment.13 Mapping of the known foci of infections is necessary in order to identify populations most at risk, their location, age groups most at risk, and which authority has the capacity to monitor, evaluate, and respond.13

Lastly, there must be a concentrated effort to educate health care providers, local medical authorities, schools, agricultural leaders, and child caregivers regarding the factors involved in the transmission of gastrointestinal parasites. Authorities must be made aware of the location of medical centers which can provide appropriate evaluation and treatment. There also has to be a concerted effort to eradicate many of the erroneous cultural and religious beliefs about parasite acquisition, prevention, and treatment.38,39

Summary and conclusion

There is a deficit of published data on the prevalence and intensity of intestinal parasitic infections in the DR, although many reports exist for Haiti, the other half of the island of Hispaniola.13 Children are at high risk for acquiring gastrointestinal parasitic infections in the DR as demonstrated by the exceptionally high percentage infection rate (99.2%) in this study. We found that G. duodenalis and E. histolytica were the most common intestinal protozoans recovered and A. lumbricoides and E. vermicularis were the most common helminths. Parasitic infections not found in this study but reported in previously published reports include hookworm, trichuriasis, and hymenolepiasis. The absence of these infections in our study is of concern to us and will be addressed in any future research in the DR. Other suggestions for research would be to perform a study of healthy and sick subjects directly from their homes. Molecular diagnostic techniques should be used in conjunction with standard fecal flotation techniques to more accurately identify parasitic infections. Any plan of action to help reduce gastrointestinal parasitic infections in children in the Punta Cana-Bávaro-Veron-Macao municipal district will require a determined effort between international, national, and local health authorities combined with the education of schools, child care providers, food handlers, and agricultural workers. A special effort must be made to reach out to both documented and undocumented immigrants working or living in the area and to pre-school-aged children or those who are not part of the public education system. Lastly, it is important to promote and protect breast-feeding as a method for disease prevention as well as to educate mothers on safe methods for food preparation during the weaning transition to solid foods.32 If gastrointestinal parasitism is to be reduced or eliminated in children of this region of the DR, future studies should address: what is considered to be safe drinking water; how effective are current methods of health education; how parasitic infection occurs in young children; and what is the role that migrant workers play in the maintenance and transmission of parasitic diseases in Verón and the rural surrounding areas.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank Adam F Childers, for his assistance with the statistical analysis and general support and encouragement. We also thank VCOM for their mission to support under-served communities, medical education and this study.

Disclosure

There is no financial disclosure to report. Kristin A Geers Childers, James R Palmieri, Mindy Sampson, and Danielle Brunet have no conflicts of interest in this work. None of the authors are receiving any financial benefit from the research conducted or from the reporting of this research. All authors actively participated in the performance of the reported research and in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

References

Saboyá MI, Catalá L, Nicholls RS, Ault SK. Update on the mapping of prevalence and intensity of infection for soil-transmitted helminth infections in Latin America and the Caribbean: a call for action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(9):e2419. | |

Ashbolt NJ. Microbial contamination of drinking water and disease outcomes in developing regions. Toxicology. 2004;198(1–3):229–238. | |

Brooker S. Estimating the global distribution and disease burden of intestinal nematode infections: adding up the numbers – a review. Int J Parasitol. 2010;40(10):1137–1144. | |

Palmieri JR, Elswaifi SF, Fried KK. Emerging need for parasitology education: training to identify and diagnose parasitic infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84(6):845–846. | |

Hotez PJ. Holidays in the sun and the Caribbean’s forgotten burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(5):e239. | |

Pan American Health Organization [homepage on the Internet]. Health in the Americas: 2012 Edition. Regional Outlook and Country Profiles. Washington, DC: PAHO, 2012. Available from: http://www.paho.org/saludenlasamericas/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9&Itemid=14&lang=en. Accessed June 19, 2014. | |

Index Mundi [homepage on the Internet]. Factbook, Countries, Haiti, Demographics. Available from: http://www.indexmundi.com/haiti/literacy.html. Accessed March 20, 2014. | |

Office of Public Affairs, Central intelligence Agency [homepage on the Internet]. The world Factbook Library. Available from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2103.html. Accessed March 20, 2014. | |

Scarpaci JL. Plazas and barrios: Heritage tourism and globalization in the Latin American Centro Histórico. University of Arizona Press; 2005. | |

Bartlett L. South-south migration and education: the case of people of Haitian descent born in the Dominican Republic. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 2012;42(3):393–414. | |

Páez Jiménez A, Pimentel R, Martínez de Aragón MV, Hernández Pezzi G, Mateo Ontañon S, Martínez Navarro JF. Waterborne outbreak among Spanish tourists in a holiday resort in the Dominican Republic, Aug 2002. Euro Surveill. 2004;9(3):21–23. | |

Vermund SH, LaFleur F, MacLeod, S. Parasitic infections in a New York City hospital: trends from 1971 to 1984. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(8):1024–1026. | |

Pan American Health Organization Communicable Disease Prevention and Control Project. Prevalence and intensity of infection of Soil-transmitted Helminths in Latin America and the Caribbean Countries: Mapping at second administrative level 2000–2010. Washington, DC; 2011. | |

Ault SK, Nicholls RS, Saboya MI. The Pan American Health Organization’s role and perspectives on the mapping and modeling of the neglected tropical diseases in Latin America and the Caribbean: an overview. Geospat Health. 2012;6(3):S7–S9. | |

PAHO. 61st session of the regional committee: Elimination of neglected diseases and other poverty-related infections. Resolution CD49.R19. Forty-ninth Directing Council; 2009; Washington DC. | |

Mackie TT, LARSH JE Jr, Mackie JW. A survey of intestinal parasitic infections in the Dominican Republic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1951;31(6):825–832. | |

Collins RF, Edwards LD. Prevalence of intestinal helminths and protozoans in a rural population segment of the Dominican Republic. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75(4):549–551. | |

Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Franco-Paredes C, Ault SK, Periago MR. The neglected tropical diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: a review of disease burden and distribution and a roadmap for control and elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(9):e300. | |

Bitran R, Martorell B, Escobar L, Munoz R, Glassman A. Controlling and eliminating neglected diseases in Latin America and the Caribbean. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(6):1707–1719. | |

[No authors listed]. Intestinal protozoan and helminthic infections. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1981;666:1–150. | |

Baum R, Kayser G, Stauber C, Sobsey M. Assessing the microbial quality of improved drinking water sources: results from the Dominican Republic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(1):121–123. | |

Periago MR, Frieden TR, Tappero JW, De Cock, KM, Aasen B, Andrus JK. Elimination of cholera transmission in Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Lancet. 2012;379(9812):e12–e13. | |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [homepage on the internet]. DPDx, Laboratory Identification of Parasitic Diseases of Public Health Concern, Diagnostic Procedures. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/diagnosticProcedures/stool/specimenproc.html. Accessed July 4, 2104. | |

Dittmar K. Palaeogeography of parasites. Morand, and Krasnov, SBR, editors. In: The Biogeography of Host–Parasite Interactions. Oxford University Press; 2010:21–29. | |

Inter-American Development Bank, Pan American Health Organization, Sabin Vaccine Institute. A Call to Action: Addressing Soil-transmitted Helminths in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2011. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&gid=13723&Itemid=4031. Accessed June 19, 2014. | |

Gates HL. The Dominican Republic, Black behind The Ears. In: Black in Latin America. NYU Press, NY, USA; 2011:119–145. | |

Gyapong JO, Gyapong M, Yellu N, et al. Integration of control of neglected tropical diseases into health-care systems: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2010;375(9709):160–165. | |

Sasidharan V, Hall ME. Dominican resort tourism, sustainability, and millennium development goals. Journal of Tourism Insights. 2012;3(1):5. | |

Carman SK, Scott J. Exploring the health care status of two communities in the Dominican Republic. Int Nurs Rev. 2004;51(1):27–33. | |

Grady C, Younos T. Water Use and Sustainability in La Altagracia, Dominican Republic. VWRRC SR49-2010; Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA. Available from: http://vwrrc.vt.edu/pdfs/specialreports/SR-49_dr_report.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2014. | |

Wooding B, Moseley-Williams RD. Needed but Unwanted: Haitian Immigrants and their Descendants in the Dominican Republic. Catholic Institute for International Relations; 2004. Available from: http://www.progressio.org.uk/sites/default/files/Needed_but_unwanted.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2014. | |

Dominican Republic Travel and Information Guide [homepage on the Internet]. Republic Education. Available from: http://www.therealdr.com/dominican-republic-life/dominican-republic-education.html. Accessed March 20, 2014. | |

Motarjemi Y, Käferstein F, Moy G, Quevedo F. Contaminated weaning food: a major risk factor for diarrhoea and associated malnutrition. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71(1):79–92. | |

Sheth M, Dwivedi R. Complementary foods associated diarrhea. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(1):61–64. | |

Rosa G, Clasen T. Estimating the scope of household water treatment in low-and medium-income countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(2):289–300. | |

WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for water Supply and Sanitation. 2012. Country Reports. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/media/files/JMPreport2012.pdf. Accessed July 4, 2014. | |

UNICEF and WHO. Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation: 2012 Update. New York: UNICEF; 2012. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/media/files/JMPreport2012.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2014. | |

McLennan JD. To boil or not: drinking water for children in a periurban barrio. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(8):1211–1220. | |

McLennan JD. Prevention of diarrhoea in a poor district of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic: practices, knowledge, and barriers. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;18(1):15–22. | |

World Health Organization. Five Keys to Safer Food Manual. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/consumer/manual_keys.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2014. | |

Newton JM, Surawicz CM. Infectious gastroenteritis and colitis. In: Diarrhea. Humana Press, NY, USA; 2011:33–59. | |

World Health Organization. Workshop for Training on Regional Guidance for Implementation of Integrated Deworming Actions. Bogotá, Colombia 13 to 15 of May 2013. Washington, DC; 2003. | |

Leung AK, Robson WLM, Davies HD. Travelers’ diarrhea. Adv Ther. 2006;23(4):519–527. | |

Stauffer WM, Konop RJ, Kamat D. Traveling with infants and young children. Part III: travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2002;9(3):141–150. | |

Ryan ET, Madoff LC, Ferraro MJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 20-2011. A 30-year-old man with diarrhea after a trip to the Dominican Republic. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2536–2541. | |

Okhuysen PC. Traveler’s diarrhea due to intestinal protozoa. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(1):110–114. | |

DuPont HL, Capsuto EG. Persistent diarrhea in travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(1):124–128. | |

Norman FF, López-Vélez R. Prevention of Tropical and Parasitic Infections. In: The Immunocompromised Traveler. Humana Press, NY, USA; 2011:551–560. | |

Baaten GG, Geskus RB, Kint JA, Roukens AH, Sonder GJ, van den Hoek A. Symptoms of infectious diseases in immunocompromised travelers: a prospective study with matched controls. J Travel Med. 2011;18(5):318–326. | |

Slack A. Parasitic causes of prolonged diarrhoea in travelers – diagnosis and management. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(10):782–786. | |

Ross AG, Olds GR, Cripps AW, Farrar JJ, McManus DP. Enteropathogens and chronic illness in returning travelers. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(19):1817–1825. | |

Neeley DF, Lechuga MT, Rochon JA, Fitzpatrick C. Stool Examinations in Immigrant New School Enrollees in New York City† 659. Pediatric Research. 1998;43:115–115. | |

Ugalde A, Homedes N, Urena JC. Do patients understand their physicians? Prescription compliance in a rural area of the Dominican Republic. Health Policy and Planning. 1986;1(3):250–259. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.