Back to Journals » Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics » Volume 13

Comparison of Social Media Use Among Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Non-ASD Adolescents

Authors Alhujaili N , Platt E, Khalid-Khan S, Groll D

Received 22 October 2021

Accepted for publication 25 January 2022

Published 1 February 2022 Volume 2022:13 Pages 15—21

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S344591

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Alastair Sutcliffe

Naseem Alhujaili,1,2 Elyse Platt,2 Sarosh Khalid-Khan,2 Dianne Groll2

1Division of Psychiatry, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine in Rabigh, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Psychiatry, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Correspondence: Naseem Alhujaili, Email [email protected]

Background: It has been well documented that social media use among adolescents is rising. However, most research has focused on social media use among typically developing adolescents and less on its use among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The goal of this study was to compare the time spent as well as to identify the purpose of social media use in adolescents with ASD compared to non-ASD adolescents.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study of adolescents between ages 13– 18 who were attending a hospital-based child and adolescents psychiatry clinic. Participants completed a self-report 18-item questionnaire to assess the pattern and reasons for using social media sites. The sample size was 26 for ASD and 24 for the non-ASD group.

Results: We found that the time spent on social media among adolescents with ASD was comparable to those without ASD diagnosis. However, participants with ASD differed from their non-ASD counterparts in both preferred social media sites as well as reasons for use. The most favourable social media site for ASD adolescents was YouTube. In contrast, the preferred social media site among adolescents without ASD was Snapchat. About 92.3% of participants without ASD reported using social media sites for primarily social interactions. In contrast, 59.1% of participants with ASD reported entertainment purposes as their primary reason for choosing a social media site.

Conclusion: Although the current study is based on a small sample of participants, the findings suggest that the pattern of usage and reasons for using social media differ significantly between the two groups. There is, therefore, a definite need for further research with a larger sample size to examine the implications of these differences and to determine how social media could be used as a tool for learning social skills and its efficacy and safety in the ASD population.

Keywords: autism, social media, adolescents, ASD and social networking sites

Introduction

Recent research suggests a significant increase in the use of social media amongst adolescents. One study reported that 81% of adolescents report using social networking sites such as Facebook.1 Social media has been described as a set of mobile and web-based platforms built on Web 2.0 technologies, and allowing users at the micro-, meso- and macro- levels to share and geo-tag user-generated content (images, text, audio, video and games) to collaborate and to build networks and communities, with the possibility of reaching and involving large audiences. This definition was based on three dimensions which are user, content format and function.2

Most of the research has focused on social media use among the general population of adolescents, but less is known about social media use among adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).3 ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social communication and interaction as well as restricted interest and repetitive behaviour.4 One study found that children and adolescents with ASD spent significantly less time using social media than typically developing participants.3 Furthermore, the majority of adolescents with ASD (64.2%) use non-social media (television, video games), while only 13.2% use social media (email, internet chatting). There is further evidence to suggest that adolescents with ASD prefer other screen time activities to social media. Another study showed that exploring websites and playing videogames were the most common activities used by adolescents with ASD, 84% and 78% respectively, while 23% used social networking sites.5 In addition, the prevalence of using social media was lower in ASD adolescents who had lower overall functional cognitive abilities and weaker conversational skills.6 Previous research regarding social media use among adolescents with ASD suggests that there is a difference in the ways and how much adolescents with ASD are using social media compared to adolescents without ASD.3,5

In a study by Mazurek, a vast majority (79.6%) of adults with ASD reported using social networking sites for social connection. These adults also reported that they perceive social media to be a comfortable way to communicate and engage with others. Furthermore, individuals who spent more time using social media were also more likely to have close friends.7 However, there is little research on the mode and purpose of social media in ASD adolescents.

Social media can be used as an opportunity for individuals with ASD to improve their social interaction. At the same time, individuals with ASD could be at higher risk for the harmful effects of social media use like obesity, internet addiction and cyberbullying.8 In a study by Kuo,5 adolescents with ASD who reported using social media were found to have better friendship quality and greater security in their friendships. Adolescents with ASD who visited websites for establishing or maintaining relationships reported more positive overall friendships than those who did not visit such websites. However, the association between better friendship quality and security and social media use does not hold true for adolescents without ASD.9

In contrary, a study by Suzuki showed an association between higher ASD traits with inappropriate manners in social networking use, which then can contribute to the feeling of loneliness among adults with ASD.10

Thus, it is all the more important to compare social media use among adolescents with ASD and non-ASD adolescents, as there is reason to believe that given the unique abilities of a person with ASD, social media may hold a special or enhanced function than it does for a person without ASD. By identifying how much time adolescents with ASD spend using social media, which sites they prefer, and their reasons for using particular sites such as for entertainment or social networking purposes, we hope to lay the groundwork for further questions regarding whether or not social media has the potential to enhance social engagement among adolescents with ASD.

While previous research has shown some discrepancy between the quantity of use of social media by children with ASD and those without, there is a gap in the literature regarding the purpose of social media use reported by adolescents with ASD.

The goal of this study is to compare how much time is spent using social media, as well as to identify which social media sites are being used, and for what purpose, among adolescents with and without ASD.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of adolescents from a hospital-based outpatient clinic. This tertiary care clinic had referrals for high functioning ASD adolescents who were being seen for co-morbid psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other behavioural disorders. Adolescents with ASD co-morbid with lower IQ or intellectual disability are referred to the Division of Developmental Disabilities Clinic. Thus, our sample did not have adolescent with lower intellectual functioning. The sample was of adolescents between ages 13–18 years who were identified as those who have ASD and those who do not. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their social media use. We hypothesized that social media use among adolescents with ASD will be different in both quantity and purpose than social media use among non-ASD adolescents, given that there are social and communication challenges experienced by ASD individuals.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Outpatient Child and Youth Psychiatry Clinic at Hotel Dieu Hospital in Kingston, Ontario. These adolescents were already assessed by child and adolescent psychiatrists and had DSM-5 diagnoses of either ASD or mood and anxiety disorders. Adolescents between ages 13–18 years with ASD or other DSM-5 disorders were recruited while they were waiting for their clinic appointment with a child and adolescent psychiatrist for a follow-up. Adolescents and their parents were asked verbally if they would be willing to participate in our research. If they verbally consented, the researcher then invited the participant and their parent to a private office to complete the questionnaire after the adolescent or their parent signed consent; the researcher was present at the time of filling the questionnaire to answer participants’ questions. The researcher who was a child and adolescent psychiatrist reviewed participant’s files with their consent to confirm that these adolescents were diagnosed with ASD by a child and adolescent psychiatrist using the DSM-5 criteria as well as the Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule. For our control population, we confirmed by reviewing their files that they have different diagnoses than ASD and were within the same age range. Severe intellectual disability and psychotic disorder were excluded. All adolescents below the age of 16 were asked to provide assent to participate, and their parents or legal guardians were asked to provide a written informed consent. Adolescents above the age of 16 signed a written informed consent. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance for this research was obtained from The Queen’s University Health Sciences & Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (HSREB) TRAQ#6023157.

Measures

Participants completed a self-report 18-item questionnaire designed for the current study to assess the pattern and reasons for using social media. Though there are a number of detailed scales constructed to measure social network sites engagement, we developed a focused questionnaire targeting the current study’s objective [Appendix]. Included in the questionnaire were the participants’ age, gender and school grade. The participants were asked if they were a member of any social media site. If the participant responded with a “no”, they were then asked to choose the reason why they do not use social media. If the participant responded “yes”, they were then asked questions about time spent on social media daily, the reason for using social media in general, and the reason for choosing a preferred social media site. They were also asked about the information they would display on their public profile as well if they would accept strangers’ friend requests. As well, how many of their social media friends had they met in person?

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25. Mann–WhitneyU test was used to compare ASD and non-ASD demographic data and social media use. A Chi-square test was conducted to evaluate if the proportion of categorical responses for each question was significantly different between ASD and non-ASD groups.

Results

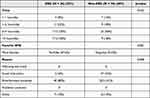

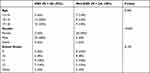

The sample size was 26 for ASD and 24 for the non-ASD group. There was no statistically significant difference between age, grade, or social media use in either group, but there were significantly more males in the ASD group (p<0.001) compared to non-ASD group [Table 1].

|

Table 1 Participants’ Demographics |

There was no difference in the proportions of “On average, how long do you spend on social media daily?” p = 0.553. However, 35% of adolescents with ASD spend more than five hours per day on social media compared to 18% non-ASD adolescents [Table 2].

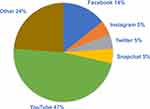

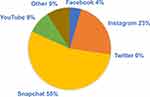

Twenty-two adolescents with ASD and twenty-one adolescents without ASD responded with their favourite social media site. A chi-square test of proportions was applied to analyze whether the proportion of preferred social media sites differed between adolescents with ASD and those without ASD.

These data reflect a statistically significant difference in proportion for preferred social media sites between adolescents with and without ASD, Pearson chi-square value: 20.58, df = 5, N = 43, p = 0.001. The most favourable social media site for ASD adolescents was YouTube. In contrast, the preferred social media site among adolescents without ASD was Snapchat [Figures 1 and 2].

|

Figure 1 This figure depicts the most favoured social media sites among ASD group. |

|

Figure 2 This figure depicts the most favoured social media sites among non-ASD adolescents. |

Sixteen participants with ASD and twenty-two participants without ASD provided a reason for their preferred social media site. Of those who reported using social media sites for primarily social interactions, 7.7% were participants with ASD (92.3% did not have ASD). In contrast, those who reported entertainment purposes as their primary reason for choosing a social media site, were primarily (59.1%) those participants with ASD (40.9% did not have ASD). These data reflect a statistically significant difference in proportion of purpose of social media site use between the two groups, Pearson chi-square value: 9.66, df = 2, N = 38, p = 0.008.

Discussion

The amount of social media use for both samples was quite similar, this finding is consistent with a previous case control study that reported similar daily duration of viewing screen-based media among ASD children compared to their siblings.11 However, in our sample, adolescents with and without ASD differed in which social media sites were preferred and why. One significant difference was the preference for YouTube among adolescents with ASD over other social media sites. In correlation with this finding, adolescents with ASD also reported their primary reason for using social media for entertainment purposes, rather than for social interactions as was reported in the non-ASD population. This also accords with earlier observations which showed that children with ASD use media for social interaction less frequently.12 As ASD is characterized by deficits in social interactions, these findings are consistent with our understanding of the disorder. YouTube can be enjoyed as passive consumption of entertainment media and it does not require the same effort for social interactions compared to other platforms such as Snapchat.

There are two main implications of this finding regarding the relationship between social media use and the health and well-being of adolescents with ASD that we will discuss in this paper. The first is the potential of social media to be used as a tool for social interaction among adolescents with ASD. Despite the fact that there is some evidence to suggest that social media may have a role in enhancing friendships and social interactions among adults and adolescents with ASD, it does not appear that the adolescents in our sample are using it as such. One study by Ward et al13 found that social media use by adults with ASD, specifically Facebook use in moderation, may enhance well-being and may be a protective factor against secondary mental health concerns common in this population.

In another study by Hedges et al14 regarding technology use as a support tool in schools for adolescents with ASD, it was found that adolescents with ASD use technology to increase their independence, enhance their social opportunities, and relieve their anxiety and stress. It is argued that social media, email, and texting can expand opportunities for social interactions and can be far less intimidating for adolescents with ASD who often struggle to engage in face-to-face relations.14 Thus, it is interesting to find that although there is evidence to suggest that social media could be used as a social tool among adolescents with ASD and possibly increase their feelings of happiness and improve the quality of their friendships, it currently is not being used as such among our sample. This gives rise to further questions such as should clinicians be encouraging the use of social media in ASD individuals, and if so, how? The answers to these questions are beyond the limits of this study, however, what this study brings to light is that this is an area in need of further research.

The second implication of the results of this study involves the possible resulting harm of social media use among adolescents with ASD. Although it is not statistically significant compared to their non-ASD counterparts, ASD adolescents spent more than five hours per day on social media, a finding in keeping with previous studies.8 There are significant health implications to such high volumes of screen time. Obesity is a rising trend among adolescents in general, however, research suggests that adolescents with ASD have a 1.42 greater risk of developing obesity than adolescents without ASD.15 Therefore, there is reason to be cautious about the time spent on social media among adolescents with ASD because of the role screen time and technology plays in establishing a sedentary lifestyle with limited opportunities for physical activity. In addition, the use of digital technologies increases adolescents’ risk of cyber victimization, and research suggests that adolescents with ASD are twice as likely to be victims of cyber bullying than their peers without ASD.16

In summary, by shedding light on the amount and purpose of social media use among adolescents with ASD, this study provides direction for further areas of exploration. A major area yet to be researched is the potential role for social media as a tool for learning social skills.17,18 One further consideration is that autism is a spectrum disorder, and varying abilities and personal characteristics must be taken into account in order to locate the role for social media in skill development.19 At the same time, if this is an area to be pursued, more research must be put into protecting adolescents with ASD from the potential harms of social media use such as obesity and cyber victimization. Limitations of this study include a small convenient sample and reliance on a self-reported questionnaire. In addition, we did not investigate the role that gender differences play in social media use, despite the fact that our sample of participants with ASD was overwhelmingly male.

Conclusions

In conclusion, usage of social media among adolescents with ASD is as frequent as its usage among adolescents without ASD. However, their pattern of usage and reasons for using social media differ significantly. There is previous evidence to suggest that social media could play a role as an intervention for teaching social skills to adolescents with ASD. However, the findings from this study do not suggest that this is currently how social media is being used by the adolescents in our sample population.

Data Sharing Statement

All data are fully available upon request from the primary author.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work and no financial disclosures.

References

1. Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, et al. Teens, social media, and privacy. Pew Res Center. 2013;21:2–86.

2. Ouirdi ME, Segers AJ, Henderickx E. Social media conceptualization and taxonomy: a Lasswellian framework. J Creative Commun. 2014;9:107–126. doi:10.1177/0973258614528608

3. Mazurek MO, Wenstrup C. Television, video game and social media use among children with ASD and typically developing siblings. J Autism Develop Disord. 2013;43:1258–1271. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1659-9

4. American Psychiatric Publishing. Autism Spectrum Disorder, 299.00 (F84.0). In: American Psychiatric Association, editor. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

5. Kuo MH, Orsmond GI, Coster WJ, et al. Media use among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2014;18:914–923. doi:10.1177/1362361313497832

6. Mazurek MO, Shattuck PT, Wagner M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of screen-based media use among youths with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1757–1767. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1413-8

7. Mazurek MO. Social media use among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Comput Human Behav. 2013;29(4):1709–1714. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.004

8. Gwynette MF, Sidhu SS, Ceranoglu TA. Electronic screen media use in youth with autism spectrum disorder. Child Adolescent Psychiatric Clin. 2018;27:203–219. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2017.11.013

9. Van Schalkwyk GI, Marin CE, Ortiz M, et al. Social media use, friendship quality, and the moderating role of anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Develop Disord. 2017;47:2805–2813. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3201-6

10. Suzuki K, Oi Y, Inagaki M. The relationships among autism spectrum disorder traits, loneliness, and social networking service use in college students. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(6):2047–2056. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04701-2

11. Al-Ansari AM, Jahrami HA. Screen based media use among children with autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactive disorder and typically developing siblings. Autism Open Access. 2020;10:246. doi:10.35248/2165-7890.20.10.246

12. Stiller A, Mößle T. Media use among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Rev J Autism Develop Disord. 2018;5(3):227–246. doi:10.1007/s40489-018-0135-7

13. Ward DM, Dill-Shackleford K, Mazurek MO. Social media use and happiness in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Behav Soc Net. 2018;21:205–209. doi:10.1089/cyber.2017.0331

14. Hedges SH, Odom SL, Hume K, et al. Technology use as a support tool by secondary students with autism. Autism. 2018;22:70–79. doi:10.1177/1362361317717976

15. Matheson BE, Douglas JM. Overweight and obesity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): a critical review investigating the etiology, development and maintenance of this relationship. Rev J Autism Develop Disord. 2017;4:142–156. doi:10.1007/s40489-017-0103-7

16. Wright MF. Cyber victimization and depression among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: the buffering effects of parental mediation and social support. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2018;11:17–25. doi:10.1007/s40653-017-0169-5

17. Shane HC, Albert PD. Electronic screen media for persons with autism spectrum disorder: results of a survey. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1499–1508. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0527-5

18. Martins N, King A, Beights R. Audiovisual media content preferences of children with autism spectrum disorders: insights from parental interviews. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(9):3092–3100. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03987-1

19. Passerino LM, Santarosa LM. Autism and digital learning environments: processes of interaction and mediation. Comput Educ. 2007;51:385–402. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.015

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.